A memento of Mörike

When Eduard Mörike arrived in Tübingen to begin his studies at the Stift in 1822, the times had already changed. The previous year, the Emperor who had turned the world upside down all over Europe had died rather a miserable death on a rocky outcrop in the desolate wastes of the South Atlantic, and his precursor, the trailblazer with the red Phrygian cap, had also long since vanished from the stage of history. Now the firebrand of the Revolution is only evoked to give a fright to little children. Through their startled eyes we see it flare up one last time outside the window, see it once more burst in at the gate, watch the flames rise from the roof beams and our house collapse in ruins. At the end of this terrible recollection, though, we learn that all that was a very long time ago, and the fire-raiser among us no longer:

Ein Gerippe samt der Mützen

Aufrecht an der Kellerwand

Auf der beinern Mähre sitzen

Feuerreiter, wie so kühle

Reitest du in deinem Grab!

Husch! Da fällts in Asche ab.

Ruhe wohl,

Drunten in der Mühle!

[Time passed—and a miller found

The rider’s skeleton, cap and all,

Leaning on the cellar wall

Still upon his bony mare.

Fire rider, oh, how coldly,

You ride to your grave, so boldly!

Whoosh, to ashes all does fall.

Rest in peace,

Rest in peace,

Below there in the mill!]

If, for the young Mörike, the terrors of the Revolution have already receded into a legendary and distant past, the closing acts of the Napoleonic era—the battles of Leipzig and Waterloo, which as a child he must have heard a great deal about—surely formed part of his own memories; and part of the dawning consciousness of his generation was shaped by the hopes for the sovereignty of the people which liberation from French rule was supposed to bring about. The “wild poet” Waiblinger, whom Mörike met in 1821 and whose writings for a long time continued to hold fast to the revolutionary ideal, is the most apt witness to this. Despite the heavy hand with which the states of the Holy Alliance had been governed for almost a decade, the dream of a national uprising was not yet dead. The clearly drawn lines of 1812 had, however, long since become blurred. Increasingly, visions of the future were becoming less and less clear-cut, and in the minds of the occupants of the Tübingen Stift, too, were becoming refracted into that ur-German blend of revolutionary patriotism and bourgeois circumspection, romantic imagination and double-entry bookkeeping, political zeal and poetical effusiveness, in which the progressive elements can scarcely any longer be distinguished from the reactionary. “On the one hand, there was great enthusiasm, with the likes of Byron, Waiblinger and Wilhelm Müller … for the Greek Wars of Independence against the Turks, and on the other hand a yearning for the contentment of peace, hearth and home,” writes Holthusen in his monograph on Mörike, in this context also recalling the well-known pen-and-ink drawing by Rudolf Lohbauer showing

the artist and his friends “drinking and smoking in a Tübingen summerhouse which he had furnished as a kind of buen retiro.” In this picture, which gives a clear idea of the way the atmosphere of those years oscillated between the impulses of political awakening and retreat from the world, we see, gathered together in the lamplight, five young men dressed in the kind of fanciful costume fashionable at the time as a gesture of rebellion against authority, part olde-worlde German, part modishly rakish: open-necked shirts with wide flowing sleeves, Renaissance berets and suchlike extravagant headgear, sideburns and unkempt locks and those strange small steel-rimmed spectacles which have clearly been the hallmark of the conspiratorial intelligentsia since time immemorial. It is not immediately apparent whether this subversive style, which was all the rage at the time, was actually an expression of militant liberalism or whether it was mere playacting and fancy dress, but one would not be far wrong in assuming that the revolutionary impulse of the Wars of Independence was, from 1820 onward, beginning to dissolve in a fug of tobacco smoke and Biergarten bravado. For almost the whole of the nineteenth century, indeed, one could say that the Stammtisch took the place of parliament in Germany. Perhaps this is why, at barely eighteen, Mörike already detects the false notes in the enthusiastic eulogies held by the would-be avant-garde in praise of Kotzebue’s murderer, Sand. Admittedly Mörike was, from the outset, even more inclined to resignation than most. In this he is a true representative of a generation which, still just touched by the breath of a heroic age, is preparing to enter upon the becalmed waters of the Biedermeier, in which bourgeois domesticity takes precedence over public life and the garden fence becomes the boundary of a life en famille which conceives of itself as a universe in its own right.

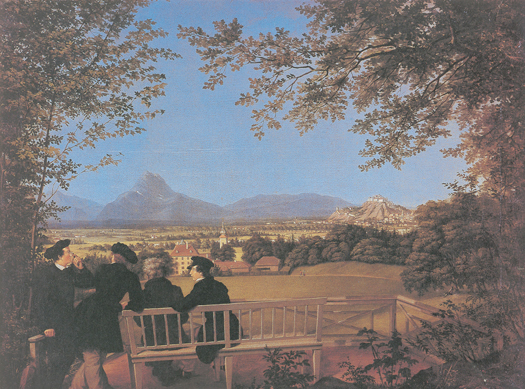

The calm of the domestic interior and the projection of an image of peaceable domesticity onto the surrounding landscape is one of the recurring motifs of Biedermeier painting. A sparsely furnished study, pale green walls, scrubbed floors of bleached pine, children playing table skittles, a parrot or parakeet in a cage, a young woman at the window, a sailing ship outside in the harbor, or in the far distance, beyond fields and hedgerows, the foothills of the Vienna Woods—Nature domesticated. The view of Salzburg painted by Julius Schoppe in 1817 shows a small group of men gathered on a bench in the foreground—the artist and his comrades, like Lohbauer’s Tübingen friends, recognizable by their apparel as sympathizers of the progressive national cause. Yet what could possibly be improved upon in this perfectly ordered prospect? Framed by greenery, overarched by a radiant blue sky, it is the very image of perfection.

A light veil of shadow lies across a field smooth as an English lawn below the terrace on which they are gathered to admire the view, and two tiny figures are walking along the path leading to Schloss Aigen, with the plains beyond gleaming in the sunlight; neatly clipped round trees line a long avenue, and beneath the castle the towers and houses of the city, surrounded by the wide blue arc of the mountains, shimmer in the sun. Exactly so, in Mörike’s work Das Stuttgarter Hutzelmännlein [The Cobbler-Goblin of Stuttgart], the Schwäbische Alb appears, seen from the Bempflinger Höhe, as the wondrous glass-blue wall beyond which “as he was told as a child, lie the cockleshell gardens of the Queen of Sheba.” If we gaze into this safely bounded orbis pictus for long enough, we can easily imagine that here someone has stopped the clock and said: this is how it should be forever after. The ideal world of the Biedermeier imagination is like a perfect world in miniature, a still life preserved under a glass dome. Everything in it seems to be holding its breath. If we turn it upside down, it begins to snow a little. Then all at once it becomes spring and summer again. It is impossible to imagine a more perfect order. And yet on either side of this apparently eternal calm there lurks the fear of the chaos of time spinning ever more rapidly out of control. When the young Mörike begins writing, he has at his back the revolutionary upheavals of the end of the eighteenth century, while the terrors which herald the new age of industrialization are already silhouetted on the horizon, the turmoil unleashed by the accumulation of capital and the moves toward centralization of a new, cast-iron state authority. The Swabian quietism Mörike subscribed to is—like all the Biedermeier arts—a kind of instinctive defense mechanism in the face of the calamity to come. In actual fact the everyday life of the time was far less secure than today’s envious observer might imagine. Everywhere in the work of Grillparzer, Lenau, and Stifter, dark abysses open up in their tales of family life: fear of bankruptcy, ruin, disgrace, and déclassement. There are children who drown themselves in the Danube, brothers in prison or in the asylum, suicide and syphilis. Mörike, never far from the brink of financial ruin after he resigned his living as a vicar, knew from at least the age of thirteen—when his father died following a stroke—how precarious life in bourgeois society could be. His hypochondria, the mood swings he was constantly prone to, his feelings of faintheartedness, and the weariness of which he so often speaks; unspecified depressions, symptoms of paralysis, sudden weakness, vertigo, headaches, the terrors of uncertainty which he continually experiences—all these are symptoms not only of his melancholic disposition, but also the spiritual effects of a society increasingly determined by a work ethic and the spirit of competition. Things are sometimes so bad that he goes around “like a frightened chicken” or “a stupid child who cries at everything.” In his request to be released from his duties addressed to King Wilhelm I in 1843, he describes how at his last christening—after he had already had to call upon the assistance of a neighboring cleric during the morning sermon—he suddenly felt so unwell that “the congregation as well as I myself expected me to fall unconscious.” Mörike’s fainting fits, and the impotence they express, are not least responses to the increasing consolidation of power in Germany, in the face of which he finds it ever more difficult to maintain his position in office, let alone hold his own as a poet in the new nation. Throughout his life he progressively retreats further and further from the exertions of artistic production, occupying himself with the revision of his novel, translating, busying himself with the composition of humorous poems and a long tail of occasional verses—engraved on a plant pot from Lorch for Wolff’s wife; with the famous Schöntal recipe for pickled cucumbers for Constanze Hartlaub; on the occasion of the dedication of the Stuttgart Liederhalle, and suchlike—and he doubtless often fears amid all this that he has lost sight of the true thread of his writing, and that quite possibly he will soon be sitting up in bed, like his father after the stroke, with his pen in his trembling hand, searching for the right expression and completely incapable of finding it.

Plagued by inner anxieties and constrained economically—as he had been from the outset, and continued to be during his more than three decades as a retired minister—apart from two trips to Lake Constance and an excursion across the border into Bavaria, Mörike never, so far as I am aware, ventured beyond the narrow confines of his native Württemberg. Ludwigsburg, Urach, Tübingen, Pflummern, Plattenhardt, Ochsenwang, Cleversulzbach, Schwäbisch Hall, Nürtingen, Stuttgart, and Fellbach—these were his staging posts in an age otherwise in the grip of railway mania, stock market speculation, risky credit deals, and general expansionism. The peaceful backwater of the Biedermeier age resembled a wishful utopia erected against progress, a painted screen disguising a world radically changing from the very foundations and opening up to new influences on all sides. Only once, as a young man, did Mörike venture beyond the limits of the Kingdom of Württemberg, when he composed his South Sea fantasy—perfect for opera—of the land of Orplid. The inspiration for this draws less on the idea, by then almost forgotten, of the Noble Savage than it anticipates the era which Mörike almost lived to see, in which, in the new imperial capital of Berlin, allotment settlements are created with names like Frohe Eintracht [Cheerful Harmony], Ostelbien [East of Elbe], Alpenland [Alpine Lands], and Burenfarm [Boer Farm], names that owe their origins not only to the expansion of the Vaterland from the Adige to the Belt, but also to the colonialist aspirations to a German Africa and a German Tahiti. While Mörike was busy writing in Cleversulzbach or Schwäbisch Hall, the scale and proportions of the world were shifting in unpredictable ways. The Texan Consul

had a villa built for himself among the Stuttgart vineyards, and the Kingdom of Württemberg became an anachronism; it became necessary to think on a grand scale, and work en miniature was abandoned in favor of a monumentalism enacted ever more recklessly from decade to decade. Nor was Mörike’s own writing unaffected by this development. His novel Maler Nolten [Nolten the Painter] is an experiment on a grand scale, in which over the course of several hundred pages an extraordinarily complex plot is unfolded. The young artist Theobald Nolten, as Birgit Mayer writes in her introductory book on Mörike, “makes the acquaintance, via his former servant Wispel, of the newly successful artist Tillsen and sees his career advanced by the latter. Through Tillsen, Nolten is introduced to the society of Count Zerlin, and, believing himself deceived by the—alleged—infidelity of his fiancée, Agnes, falls in love with the Count’s sister, Constanze. From this point on, fate takes its course. His relationship with Agnes had been on the one hand undermined by an intrigue on the part of the gypsy girl Elisabeth, yet on the other sustained—or so it appears—by a counterintrigue in Nolten’s name by his friend, the actor Larkens. The negative climax of the novel is reached when Constanze breaks with Nolten after finding out how things really stand. Verse interludes, a magic lantern show, and idyllic interpolations form a precarious counterbalance to the looming threat but cannot avert it. In the further course of the action all the characters become ever more deeply enmeshed in secretive and tragic mutual dependencies, which in the end none of them survives.” From this deliberately abbreviated summary, which can scarcely begin to do justice to the emotional and social complexities involved, one may deduce that Mörike was beginning to lose his way in this ambitious undertaking, freighted as it was with subsidiary characters and episodes, interludes and subplots, and all manner of digressions and diversions. If his myopic eyes are often able to detect hidden wonders in the smallest detail, his eye grows dim if it falls on a wider panorama, and the twists and turns of fate which he invents for his characters soon dissolve into melodrama: “The clock was just striking eleven. In the Zerlin household all had grown still, only in the bedroom of the Countess do we still find the lights burning. Constanze, in her white nightclothes, sitting alone at a small table near her bed, is busy letting down her beautiful hair, taking off her earrings and her delicate string of pearls, which always adorned her neck with such simple charm. Lost in thought, she held the necklace on her little finger up to the light, and if we rightly read her brow, it is Theobald of whom she is thinking.… Restlessly she arose, restlessly she stepped to the window and let the magnificently bright heavens with all their portent, with all their splendor, act upon her. Her love for that man, from its first imperceptible stirrings to the astonishing state of her full awareness of it, from that moment in which her feelings had already become yearning and even desire to the pinnacle of the most powerful passion—that whole range she now traversed in her mind and found it all beyond comprehension.” Immediately after this somewhat dubious passage we learn of Nolten’s “irresistible ardor,” of the “full sweet ferment” of love which “enveloped the senses” of the Countess in her remembered scene in the grotto; of “the womb of an all-knowing fate,” of “ardent gratitude” and “most heartfelt pleas.” The inflamed passion of elective affinities Mörike may have had in mind has inadvertently evolved into something precariously close to a better class of sensationalist romance, and among the vistas of parks and gardens which he has erected on the narrative stage, our Swabian vicar—who unfortunately is by no means at home in this aristocratic milieu—wanders around rather gloomily and just as aimlessly as poor Schubert in Rosamunde or in Berté’s Dreimäderlhaus. Like those of Mörike, Schubert’s theatrical and operatic ambitions—which he hoped would lead to rapid success and at least a temporary relief from his financial dependence on his friends—often misfired, and, as on occasion in Mörike’s poetry, so, too, in Schubert’s works the most masterful strokes of genius are most readily to be found in the hidden shifts of his chamber music, for example the opening of the second movement of his last piano sonata, or in the song “Die liebe Farbe” from Die schöne Müllerin; in those true moments musicaux where the iridescent chromatics begin to shimmer into dissonance and an unexpected, even false change of key suddenly signals the abandoning of all hope, or, alternatively, grief gives way to consolation. Mainly it is the Moravian Dorfmusikanten [village musicians] whom one sees Schubert accompanying on their travels from village to village. He is more at home with them than he is toiling away at the high art which bourgeois notions of culture demand. Indeed, there is a portrait of Mörike in which he looks almost exactly

like the twin brother of the Viennese composer. Both were working at the same time, one looking out onto a Swabian apple orchard, the other in Himmelpfortgrund, both attempting a form of composition which seeks to re-create, in a snatch of half-vanished melody, that authentic Volkston which in fact has never existed as such.

Den schon die Ferne drängt,

Noch in das Schmerzensglück

Der Abschiedsnacht versenkt.

Ein dunkler See vor mir,

Dein Kuß, dein Hauch umweht

Dein Flüstern mich noch hier.

An deinem Hals begräbt

Sich weinend mein Gesicht,

Und Purpurschwärze webt

Mir vor den Augen dicht.

[Thus, while the distant view

Now claims my timid sight,

It dwells on leaving you:

That bitter joy, last night.

The dark lake of your eye

Still glimmers for me here,

Your kiss endures, your sigh,

Your whisper at my ear.

My weeping face still grieves

As on your breast it lies;

A purple blackness weaves

Its skein across my eyes.]

The mistake we always make as listeners is to imagine that these miracles of composition, language, and music are drawing directly upon their natural heritage, whereas in fact they are the most artificial thing about it. What it takes to produce these effects remains, now as then, an undisclosed mystery. Certainly a rare adeptness at their craft, permitting the most minute adjustments and nuances; and then, or so I imagine, a very long memory and, possibly, a certain unluckiness in love, which appears to have been precisely the lot of those who, like Mörike and Schubert, Keller and Walser, have bequeathed to us some few of the most beautiful lines ever written.

Not for nothing is Mörike’s work haunted by the spirit of the Swiss vagabonde Peregrina, whom at the time the young poet did not dare to stay with and whom he sent on her way “in silence,” as he remorsefully writes, “into the wide gray world.” For this enforced sacrifice of true love for the sake of the conventions of bourgeois society, which is the subject of the “Peregrina” cycle and the echoes of which resonate now here, now there, in his work, Mörike pays for the rest of his life by the fact that he is surrounded by his mother, his sister, her friend his wife, and his daughters, trapped within an allfemale household which is nothing more nor less than a travesty of the matriarchal order to which, at heart, all men long to return. This, it seems to me, is the subject of the Historie der schönen Lau [Story of the Beautiful Lau], a water nymph with long flowing hair from the Danube delta exiled to the Blautopf near Ulm, whose body resembles in all ways that of a natural woman save that “between her fingers and toes she has webbing white as blossom and more delicate than the petal of a poppy.” This fairy tale, sprinkled with a number of obscure, almost surreal Swabian dialect words, such as Schachzagel, Bartzefant, Lichtkarz, Habergeis, and Alfanz, has as its matriarchal protagonist Frau Bertha Seysolffin, the stout landlady of the Nonnenhof, the inn at the former convent next to the Blautopf, who “also is a true foster mother to poor traveling journeymen.” In her garden “the great golden pumpkins hang in autumn all the way down the slope to the pool.” Just next door is the monastery, where the men keep their own company. Sometimes it so happens that the abbot comes out for a walk and takes a look to see if the landlady happens to be in her garden. On one such occasion in the story he also surprises her bathing in the Blautopf, greeting her with “such a smacker of a kiss that it echoed off the church tower,” reverberating all around, from the refectory, the stables, the fish house, and the laundry, where it dingdongs back and forth between bucket and tub. Here, clearly, the right people have come together. At any rate one can easily imagine what act is being rung in by the great dingdong Mörike describes, even if, for the sake of decency, he glosses over the main action, noting only that the abbot, alarmed at the noise, rapidly waddled off. The fairy-tale happiness experienced by the two stout folk by the water’s edge in Ulm harks back to a time when men and women were not bound to each other two by two, but merely appeared from time to time on the other’s horizon, rather like the moon, which one doesn’t see all the time either.

The story of the beautiful Lau is, of course, a story within a story, built into another tale about Seppe, a shoemaker’s journeyman apprentice from Stuttgart who one day leaves his hometown and goes “at first,” as it says, “as far as Ulm.” The story revolves around the fact that Seppe mixes up the two pairs of magic shoes given to him by the Hutzelmännlein—the eponymous “cobbler-goblin”—one of which, the narrator reveals, “is blessed and destined for a girl,” with the result that on his journey he has great difficulty in walking. Only when he arrives back home in Stuttgart are the mismatched shoes reunited of their own accord with the feet that they are meant for, one happy pair on his own feet and the other on those of the girl Vrone, so that at the Stuttgart Fastnacht celebrations these two Swabian protégés of the Hutzelmännlein, without any rehearsal, are able to perform acrobatic feats high above the heads of the crowd, so daring that “it was as if they had been tightrope walking all their lives.” All their actions, the narrator relates, “seemed like a lovely web which they wove in time to the music.” “Seppe,” so the story continues, “as he danced did not look at the narrow rope beneath his feet, still less at the people below; he had eyes only for the girl—and when they both met in the middle he took her by the hands, they stood still and gazed fondly upon one another; and he was seen secretly to exchange a word with her. Then he suddenly leapt behind her and, turning their backs to each other, they stepped out in opposite directions. When he reached the crossing rod he stopped, waved his cap in the air, and cried out heartily, ‘Long live all the ladies and gentlemen.’ Then the whole market cried out as one, Vivat! three times, to each in turn. Amid all the noise and confusion and the fanfare of the trumpets, pipes, and drums, Seppe ran across to Vrone, who was standing at the opposite end, caught her in his arms, and kissed her for all the world to see.” In this fantasy of erotic wish fulfillment in the dance of two beings high above the earthly sphere, risen above the abyss in which society cowers, a man who has long since given up on the idea of reciprocal love rather late in life imagines one last time how different things might have been if, at the time, he had run off with the by all accounts unusually beautiful and mysterious vagabonde, Maria Meyer, and pursued a different kind of mountebank career from that of writing—that rather

vicarious vice whose clutches those who have once embarked upon it rarely succeed in escaping. And so we see Mörike at the last sitting in the garden surrounded by his wife’s relations on a hot summer’s day, the only one with a book in his hand, and in the end not very content in his role as a poet, from which—unlike his clerical calling—he can no longer retire. Still he has to torment himself with his novel and other such literary matters. But for years now the work has not really been going anywhere. The painter Friedrich Pecht, in a reminiscence from this time, relates how on several occasions he observed Mörike noting down things which came into his head on special scraps and pieces of paper, only soon afterward to take these notes and “tear them up again into little pieces and bury them in the pockets of his dressing gown.”