3

The Functions of Emotion in Infancy

The Regulation and Communication of Rhythm, Sympathy, and Meaning in Human Development

Colwyn Trevarthen

In healthy families, a baby forms a secure attachment with her parents as naturally as she breathes, eats, smiles and cries. This occurs easily because of her parents’ attuned interactions with her. Her parents notice her physiological/affective states and they respond to her sensitively and fully. Beyond simply meeting her unique needs, however, her parents “dance” with her. Hundreds of times, day after day, they dance with her.

There are other families where the baby neither dances nor even hears the sound of any music. In these families she does not form such secure attachments. Rather, her task—her continuous ordeal—is to learn to live with parents who are little more than strangers. Babies who live with strangers do not live well or grow well.

—Hughes (2006, p. ix)

EMOTIONS HAVE HEALING power because they are active regulators of vitality in movement and the primary mediators of social life. From infancy, emotions protect and sustain the mobile embodied spirit and oppose stress. And they do so in relationships between persons who share purposes and interests intimately (Trevarthen, 2005a). By marking experiences with feelings, emotions allow us to retain a record of the benefits and risks of behaviors, and they give values to the intentions and goal objects of those behaviors (Freeman, 2000; Panksepp, 2005a). Most importantly, human emotions link persons in the life of family and community; they communicate the well-being, cooperation, and conflicts of our engaged lives (Smith, 1759/1984; Zlatev, et al., 2008).

The growing life of children is protected by powerful moral and aesthetic feelings that assist them to learn in companionship with adults, to gain from their larger experience, and to become actors with adults in a meaningful world, with its conventional likes and dislikes and demanding practical tasks (Bråten, 1998; Dissanayake, 2000; Donaldson, 1992; Reddy & Trevarthen, 2004; Trevarthen, 2002, 2005a&b). With the guidance of emotions that engage them with others and that estimate how they are appreciated, individual human beings find roles and personality in society, while mastering the historically accumulated knowledge and skills of a culture (Gratier & Trevarthen, 2008; Legerstee, 2005; Stern, 2000; Trevarthen, 1989, 1998, 2001a). Learning about persons and things plays an essential creative role, but there is a strong and willing foundation of motives and innate emotions that animate and evaluate learning. In a way, that is what I mean by movement: how we are animated by innate motives and emotions. Even infants experience pride in achievements, shame for failure, and guilt for wrongdoing. Pride and shame are basic self-and-other human feelings, essential to the work of relationships and the regulation of consciousness; they are not learned social techniques (Draghi-Lorenz, Reddy, & Costall, 2001; Reddy, 2005, 2008; Trevarthen, 2009; Trevarthen & Reddy, 2007). Each young person’s place in the community is regulated by other basic feelings, such as admiration and envy, which cannot be reduced to sensations of pleasure and pain in a single self (Hart & Legerstee, in press).

In a psychology that places interpersonal experience at the heart of human understanding (Reddy, 2008), all the functions of emotion may be seen as acting their part in the intuitive, “self-teaching” life of an infant or toddler, and to be doing so before language gives articulation to any interpretations, beliefs, or explanations. Cognitions and “theories of mind”—though they may elaborate and guide emotions with experience—cannot, by themselves, either form emotions or heal them. Empathy, or thinking about the emotions of others, is not enough. What is required for emotional life with others to thrive is the genuine reciprocal sympathy of impulses and feelings and intuitive companionship of purposes achieved through the coordinated vitality of dynamic “relational emotions” with persons (Stern, 1993; Panksepp & Trevarthen, 2008). As is clear in the original Greek, em-pathy is a one-sided projection into (or taking in of) an emotion “about” an object by the self, whereas sym-pathy is a creative sharing of feelings, of whatever kind, “with” an other or others—seeking immediate mutual sensibility between friends or opponents (Smith, 1777/1982). The difference is that in sympathy, there is the motivation for cooperation and the social negotiation of a role (Reddy & Trevarthen, 2004), even between infants in groups (Bradley, 2008).

In this chapter I discuss findings about the emotions of infants that help explain how self–other motives and emotions guide intentions and cognitions in adults. I review facts about the formation of neural systems in the brain of the human embryo and fetus that, though homologous with systems in other species, shows unique adaptations for more elaborate, cooperative inter-individual efforts. The comparative account leads to a theory of the functions of specifically human emotions for (1) subjective regulation—informing the actions of the Self as an active embodied agent (moving) that has multiple purposes; (2) the intersubjective regulation of being moved—acting with others in intimate relationships and for the negotiation of a place or “identity” in a social world or community; and (3) the intergenerational translation of meaning in culture—the understanding of knowledge and skills.

A New Theory of the Infant Mind and A New Brain Science of Communication

Four decades ago a different descriptive method for conducting empirical research on the consciousness of infants led to a better appreciation of innate human talents and of positive feelings for intersubjective life and for the learning of meaning (Trevarthen, 1977). It also led to a new theory of basic motives that animate shared life, motives that previously had been relegated by reason to a defensive “unconscious” ruled by disturbing emotions. Medical and psychological science, focused as they have been on the elaborated rules of talk and rationality, had concluded that these talents were absent at the preverbal stage of life. The prevailing view was that a newborn infant is an organism with reflexes adapted to respond to maternal care for the body and its vital functions, aroused or soothed by stimuli, but lacking a coherent awareness of an active self and therefore incapable of a “mental’ response to the intentions of an other. In that view, the “emotions” expressed by the baby were mere signals of physiological discomfort or need. For instance, smiles were regarded as automatic, mindless expressions of visceral stimuli. As Brazelton put it, “The old model of thinking of the newborn infant as helpless and ready to be shaped by his environment prevented us from seeing his power as a communicant in the early mother–father–infant interaction. To see the neonate as chaotic or insensitive provided us with the capacity to see ourselves as acting ‘on’ rather than ‘with’ him” (1979, p. 79).

The use of films of young infants and their mothers in secure and intimate communication to make detailed analyses of timing and expression enabled Daniel Stern and colleagues in New York (Stern, 1971, 1974; Jaffe et al. 1973; Stern et al., 1975; Beebe et al., 1979), and a group of us at Jerome Bruner’s Centre for Cognitive Studies based at Harvard (Bruner, 1968; Richards, 1973; Ryan, 1974; Trevarthen, 1974, 1977, 1979), to show that infants are actually born with playful intentions and sensitivity to the rhythms and expressive modulations of a mother’s talk and her visible expressions and touches. Later, Stern described the phenomenon that guided the patterns of movement infant and mother performed together as affect “attunement” (Stern et al., 1985; Stern, 1985/2000). Condon and Sander (1974) demonstrated that the interpersonal timing of mother–infant interactions had the fine-tuning found in film studies of conversational regulations between interacting adults.

As the development of the infant’s behaviors was traced through the first year, it became clear that infants evoked “intuitive parenting”—that is, communication of dynamic mental states and the building of shared narratives of experience or “meanings” that have the rhythmic and melodic property of what Hanuš and Mechtild Papoušek called “musicality” (Papoušek & Papoušek, 1987; Papoušek, 1996). As Mary Catherine Bateson (1979) had concluded, clearly the infant’s skills, with their stimulating effects on the mother’s expressions, were adaptations not only for the learning of the symbols of language but also, as she put it, for other conventions of culture, including “ritual healing practices.” She called the intimate engagements between a mother and her 9-week-old infant “protoconversations.” Thus, the paths of discovery of the 1970s and 1980s led a number of us, independently, to accept infants as persons, instinctively endowed with emotions, seeking companionship in knowledge and skills.

Since the 1990s brain science, too, has developed observation methods that reveal activity in living brains while individuals are engaged in responding to one another’s movements (Rizzolatti & Arbib, 1998; Decety & Chaminade, 2003). We now know that there are widespread events in both cortical and subcortical regions of the brain that are specific to emotions and intentions, and that these animate the acquisition of conceptual knowledge or motor skills (Schore, 1994; Panksepp, 1998a, 2005; Damasio, 1999; Gallese, 2005; Trevarthen, 2001b). It has been made abundantly clear that the dynamic and body-related features of the brain activity that are directing and evaluating movements being made by one individual are responded to by the brain activity of another person who feels them by immediate sympathy (Decety & Chaminade, 2003; Gallese, 2003; Gallese et al., 2004; Panksepp & Trevarthen, 2009).

Actions, even a newborn’s, are intelligent and conscious (Trevarthen & Reddy, 2007; Trevarthen, 2009). The motives that coordinate their movements are the foundation of experience. The human brain is an organ evolved to formulate plans for moving, for evaluating the prospects of action emotionally, and for sharing their motives and feelings socially. The emotional expressions of one person and the sympathetic response to them excited in another individual are associated with increased activity in the same brain regions in both individuals, with the active systems including subcortical, limbic, and neocortical elements. Most remarkably, the regions of the cortex involved in both making and recognizing coordinated patterns of facial and vocal expressions, including those that will eventually produce and receive language, are already specialized for these functions in a 2-month-old infant (Tzourio-Mazoyer et al., 2002). Clearly, the human brain is both an intentional organ and an intersubjective one before it is a linguistic one, and emotions that regulate moving and being moved in intimate contact are its primary medium of communication.

Thus, developmental psychology and functional brain science come together, presenting new evidence that the infant brain is anatomically and functionally equipped with intentions and feelings. The infant brain also has within it the emotional foundations for learning and articulating symbolic conventions by identifying with the intentions and feelings other people express in their movements—the meanings of their actions (Kühl, 2007). A new psychology of infancy, of infant mental health, and of the foundations of human cooperative mental life and collaborative actions has been found (Trevarthen & Aitken, 2001).

The Psychobiology of Motives and Emotions in Infancy

To explain the competence of even newborn infants for sensitive interactions of two kinds—“body function regulating” and “psychological mind linking”—we need a psychobiological theory of emotional evaluations that are actively generated in the subcortical core of the brain, in neural systems, formed and functioning before birth, that underline motivation (Merker, 2006; Panksepp & Trevarthen, 2008). This theory needs to come first, before a theory of the plasticity of a massively impressionable cerebral cortex under the influence of imposed stimulation, rewards, and punishments. Neuropsychological researches, as well as studies of the neurochemical systems of emotion in animals, have proved that subhemispheric “environment expectant” systems activate and direct the conscious regulation of rhythmic skilled actions and the retention of episodic experiences in development (Panksepp & Trevarthen, 2009).

All adaptive actions—that is, the “movements of life”—operating at different time scales and through different periods of felt, imagined, and remembered experience, depend upon activity in innate neural networks that generate body-related space and time in motor actions, and that regulate them via sensitivity to the pace of events within and outside the body (Trevarthen, 1999, 2008b). The engagement of an infant’s actions and experience with expressions of other persons is determined by a shared sense of “attunement” for measured rhythms of moving in the present (Stern et al., 1985; Stern, 1999, 2004), and a progressive, “narrative” sense of time (Malloch, 1999, Gratier & Trevarthen, 2008). In this sense of time, the flow of energy in action and of excitement in anticipation of experiences connects the few seconds of present activity with both an imagined future and a remembered past (Trevarthen, 1999). From infancy, human interactions exhibit the “pulse,” “quality,” and “narrative” dimensions of what Stephen Malloch (1999) has defined as “communicative musicality.” A theory of the biochronology of human movement and the communal ritualization of actions interprets these panhuman regularities of intersubjective life in neurobiological terms (Malloch & Trevarthen, 2009; Osborne, 2009; Trevarthen, 2008a, 2008b).

When we are in the presence of others, even when they are at a distance and “public,” we can sense their states of interest, motivation, and self-regulation from their postures (or attitudes) and gestures in relation to circumstances, from the speed and modulation of their movements, and, if they vocalize, from the rhythms, pitch, intensity, and quality of their voices. We do not need to hear what they say. We are alert to how and where their eyes look, to the changes in facial expression, to the subtle variations of hand movement, as well as to prosodic changes in their vocalizations and speech. Most especially, we are alert to how these behaviors respond to our own motives and feelings. In very intimate contact, we feel the gentleness of their touch, sense the tension of their body, and perceive their breathing and the faintest changes in vocal expression. We gain dynamic information of their motives and cognitive state from both the movements of their body to engage with or move in the world, and from the changes of their inner proprioceptive (body sensing) and visceral states, which are made evident in their expressions and gestures (Trevarthen, 2001b, Trevarthen et al., 2009, in press). In clinical work, information may be obtained from what people say they feel, believe, or think about, and who is important in their lives. But the clinician should also know that the more intuitive expressions of the body and its affective state are also significant and will be informative about his or her contact with the client in the present moment and throughout the course of therapy (Stern, 2004).

Charting the Uses of Human Emotion

Ethologists describe emotional signals of animals that mediate in essential transactions of hunting (between predator and prey as well as in coordinated group predations), of courtship, mating, and parental care—all to sustain the cooperative society of the species. Each species has a subtle “vocabulary” of emotional signals conveyed by body movements, and many show evidence of learning the “conventions” of expression that hold together a family or larger group in the pursuit of collaborative activities (Wallin, Merker, & Brown, 2000).

The Social Emotions

In human affairs we accept that all our contacts and relationships are colored by affections of one kind or another. We have changing moods of self-confident happiness or exhausting sadness and anxiety, and these are sensitively appreciated, with more or less consideration, by other people. The ways in which others respond to our emotions affect us, giving us feelings of love and admiration or dislike, or, in cooperative affairs, of pride in the achievements we offer for their approval, or shame if we perceive we have acted badly or failed to do what was expected of us. We also situate ourselves in relation to the behaviors between others, experiencing admiration or envy, or generous pleasure or jealousy for their achievements and actions together. Even infants and preverbal toddlers are sociable beings in this sense, equipped with feelings that reflect their sense of how they fit in with peers in groups (Selby & Bradley, 2003; Nadel & Muir, 2005; Bradley, 2008; Hart & Legerstee, 2009, in press). Moreover, each of us feels we are a person who owns a character that is most succinctly described in emotional terms, telling how we seem to feel about what we do and about life with others: We are confident or timid in social presentation, quick or slow in thought and action, modest or opinionated about our views, considerate or impatient with others, creative and adventurous or methodical and controlled, likeable or disagreeable. In all their aspects, human emotional behaviors appear to be adapted to express both how we regulate our intentions and experiences and how we live with others, in relationships and in society.

Emotional forces within and between us exist in the present moment, but they also powerfully influence both what we imagine or anticipate may happen in the future and what we remember of a past that may be as long as the story of our life. Most importantly, emotions give the individuals we meet and interact with roles on our “personal narrative history.” All our histories gain social meaning by the conventions of the aesthetic and moral judgments that we invent for them, and our cultural creations serve to build a “habitation,” so to speak, in which practical actions have conventional values that reflect the emotions we share. A child learns, by negotiation with companions, different social uses for the emotions with which he or she is born (Nadel & Muir, 2005; Gratier & Trevarthen, 2008).

Infants are born not only with proprioceptive regulation of the movements of a whole conscious subjectivity or self, in the present; they are also meaning-making subjects with playful intuitions that require imaginative companions who will validate those meanings, helping new ideas for moving grow in usefulness, intersubjectively. Infants have emotions that care about the sharing of humanly invented meanings, giving them the value of “human sense” (Donaldson, 1978). Joint attention to events pointed out in the world is not enough, and words are not necessary. The crucial element is an affectively loaded mutual attention and “altero-ceptive” regulation of actions made together—the sympathy of interests and emotional evaluations expressed in movement that make cooperative awareness and joint enterprise possible and memorable (Bråten & Trevarthen, 2007).

The Embodiment of Emotions as Active Principles, Not Mere Reactions

Emotions, defined by Stern (1993) as protectors of vitality in relation to goals for actions and in relationships, not just as categories of facial expression, evidently are epigenetic regulatory states or “agencies” that grow in the mind of an organism and that adapt in creative ways, or make fitting the motives of actions (Whitehead, 1929). They make the images and plans for doing things with movement safe and workable, so that they may best fit environmental contingencies. Other persons’ sympathy enables the emotions expressed to become more than a self-expression—they acquire an intersubjective or moral value in the transactional space between self and other. The promotion of safe and workable contact with others must take account of their feelings, too, and must react to the contingencies that arise in communicative exchange of expressions and actions with them.

Key functions of emotion in attachments and the regulation of meaningful human life are as follows.

• Integration and connection with the regulation of body functions. Emotions have evolved to be both corrective and integrative for living, inside the body of an active, mobile agent or self. Emotional changes of intentions in the central nervous system (CNS) are coupled with, but not caused by, autonomic nervous system (ANS) mediated feelings of visceral and autonomic need that adjust and maintain vital state and energy resources of the body in all its organs (Trevarthen et al., 2006).

• Attention, orientation, and focusing of perception to find external goals for moving. At the same time, emotions “pay attention” to the world outside the self, aiming the foci of consciousness selectively—by locomotion and by “partially oriented” movements of limbs and special sense organs that pick up information in the several modalities—always aiming to find out what the self can perceive of what the environment may afford for future action.

• Adaptive mapping in the brain of the body in “behavior space.” Emotions judge the different prospects of moving in one dynamic body-centred representation of space and time for behavior, an egocentric “behavior field.” Emotions and emotional regulations are an intrinsic part of this adaptive mapping in the brain of the space in which a body behaves (Trevarthen, 1985).

• Future orientation for action through time. The adaptive function of any emotion in the perception of circumstances in the world, whether it is directing positive approach behavior or negative withdrawal, must be prospective—aimed to either protect the future life of the animal against possible stress, or to favor the acquisition of benefits from immediate or more distant objects and events. Human emotions depend greatly on imaginary events and circumstances, which bring great creative benefits that prepare for adventures in experience, but also the possibility for distortions in the sense of reality and its prospects, as in the delusions of schizophrenia. Anxiety from the past, real or imagined, can make the future unbearable. Emotions are the innate evaluative part of the perceptual space, weighing motives for future action in an imagined world. This world has other possible times and spaces—which multiplies the possibilities of egocentric experience.

• Memories built with emotional ties to past actions. An animal may profit from experience only if the state of affairs in the present is given appropriate or reasonably accurate emotional values that might be valid on other occasions. The emotions evoked by a situation or object are drawn from the emotions of past moments in which the same or similar situations or objects were encountered. There is a reliving of the actions with their feelings in perception; these feelings may qualify the uptake of information from the present. Emotions associated with past experiences change the processes of motivation: They can give rise to harmful phobias, addictions, and obsessions, or to aesthetic or moral evaluations that provide valuable guidance for experiencing satisfying actions in the present or to seek in the future. All creative activities are guided by emotions in this way.

• Sympathy for intentions and feelings in others. Even in primitive forms, animal emotions may be adapted for social regulatory powers, in the behavior space between individuals, intersubjectively, and these capacities are greatly elaborated in evolution (Wallin, Merker, & Brown, 2000). Social emotions of human beings, such as love, hate, pride, and shame, amplify or restrict the powers of individuals for profitable engagement with the environment by making their behaviors cooperative or competitive. Emotions between members of a couple or among members of a larger group determine how well their actions may be combined, and how well their separate experiences are shared and understood. This is true when the communication is entirely nonverbal, and remains true even when the messages communicated are intricately rational and codified in symbols. Indeed every invented symbol or agreed-upon communicative sign has both a pragmatic reference and an emotional appeal. In the creative movement of music, poetry, drama, and literature, even in philosophy, the emotional forces are strong, and they hold all elements of the story together in the composition of an affective narrative (Smith, 1777/1982; Lange, 1942; Fonagy, 2001; Kühl, 2007).

• Development of shared understanding in a world of cultural meaning. The communicative powers of emotion, active from birth in human beings, animate the formation of both life-supporting attachments for a long dependency on parental care in childhood, and the development, through lifetime cultural learning, of the accumulated consciousness of a historic community going back many centuries (Bruner, 1990; Feldman, 2002). Harmonious progress of society depends on aesthetic and moral emotions that give members a common set of values, which may or may not be articulated in beliefs or encoded in rules or laws.

Language itself depends on the emotional expressions alive in conversation. It has evolved and develops from a capacity to tell stories by mimesis (Donald, 2001), and every mimetic performance or narration is animated and carried forward by rhythmic transitions of emotional states—of expectancy or anticipation, of excitement as risks are encountered and overcome, of satisfaction in achievement, and of calm reflection after all is concluded. The poetic or creative processes reflect the “playful” emotions that make the narrative important, and the narrative is informative by virtue of how the facts it specifies fit in the “argument,” or the “drama” of what the protagonists are doing (Turner, 1996; Bruner, 1990). These are the motivating “musical” principles that guide a toddler into meaning and language. It is likely that, in the evolution of human understanding, sharing of experience by a gestural and vocal “musi-language” preceded use of words in language to specify ideas with more precision (Wallin et al., 2000).

Emotions in the Total Design of the Brain

Emotions regulate practical functions of perception, cognition, and memory as well as the generation of coordinated and controlled movements. Correspondingly, the anatomy of emotion, established in the embryonic brain before any movements are executed, is both centrally or medially integrated and widespread in its influences (Panksepp, 1998; see also Chapter 1, this volume). The expression and reception of emotional signals engage all motor organs and all modalities of sense, and a specially adapted emotional motor system (Holstege et al., 1996) conveys enhanced evidence of psychological states and their changes between persons.

The areas of the human cerebral neocortex adapted to perceive live communication and to generate the intricate patterns of expressive movement, as in speaking, are the most enlarged in comparison with other species, and they are identifiable before birth. More space is allocated in the human cortex for activating organs of dialogue: for the eyes and their movements that signal direction of interest and focus of attention; for the hands and their use in modulated gesture as well as in skilled manipulation; for hearing of expressive sounds; and for articulations of the vocal tract, jaws, lips, and tongue to make the sounds that carry meaning with feeling.

In readiness for the exceptionally long postnatal development of the human cortex, new territories of the prefrontal, parietal, and temporal parts of the primate brain have also expanded in the evolution of humans. These have key importance in the social and cultural development of the child, and they gain unique asymmetry in the skills of intelligence they assimilate through education, most notably in the production and reception of language (Trevarthen & Aitken, 1994). Limbic parts of the cortex that integrate regulations of internal state with cognitive appreciation of objects in the outside world are also greatly elaborated in the human brain, and they continue to grow throughout life. They, too, are asymmetric and give different motives and learning potential to left and right hemispheres (Trevarthen, 1996) (Figure 3.1).

Throughout the vertebrates there is an asymmetry in the vital self-regulatory functions of the core neural systems that mediate between visceral and somatic needs. The left strand of neural systems is more dopaminergic and environmentally challenging or ergotropic; the right is more adrenergic and restorative and protective of bodily functions or trophotropic (Hess, 1954).

The right half of the child’s brain has greater responsibility for receiving, for “apprehensive” affective regulation, whereas the left half is more giving, “assertive,” or proactive in expressing communicative intention toward the mother (Trevarthen, 1996). For the first 18 months, the right hemisphere of the infant brain is more advanced and growing faster than the left. This asymmetry is associated with the intense involvement of the infant in establishing attachments to the mother and a few other intimate givers of care and affection. In the second and third years, as the child develops more powers of communication and self-expression, more social independence, and begins to master the articulation of language, the left hemisphere shows a growth spurt. But even in the neonatal stage, there are asymmetries in the reception (more right hemisphere) and production (more left hemisphere) of communicative signals, including those for emotions. This deep complementarity of emotion systems supports the elaboration of human cerebral asymmetry for cognitive functions and the acquisition of cultural skills, including language.

FIGURE 3.1

Asymmetries in functions of the cerebral hemispheres, and in communicative behaviours. The neurochemical activation and arousal systems are also asymmetric: DA = dopaminergic motor activation; NA = noradrenergic sensory arousal of attention.

The Neural Nets of Self-Control

The motivational and emotional basis for the special human sensory and motor capacities to make and receive expressions of communication and the regulation of their affecting qualities and dynamics occur subcortically, centered on the periaqueductal gray (PAG), where all emotion-mediating neurochemical systems converge on a coherent self-representation of the organism to constitute a primordial “core consciousness” (Damasio, 1999; Panksepp, 1998; Merker, 2005) that is sensitive to positive affective influences from other individuals, transforming them into rewarding neurochemistry (Panksepp, 2005).

Conscious control of movement in a complex, highly mobile human body with many “degrees of freedom” (Bernstein, 1967) depends on a unique central time sense and core control of effort in whole-body biomechanics—integrating a flexible trunk with head, arms, and legs, with “prospective control” (Lee, 2005). This rhythmic control, coherence, and regulation of energy are mediated by a widespread subcortical system of neural connection. An integrated intrinsic motive formation (IMF) coordinates the parts of a mobile body and is formed in subcortical and limbic systems of the embryo before the cerebral cortex. The IMF functions throughout life to (1) direct the movements of the sense organs and effectors to select goals and objects in the environment, (2) evaluate their benefits or risks for the life of the whole self, and (3) express its states and react to the movements of other selves while detecting their intentions and feelings (Trevarthen & Aitken, 1994; Panksepp & Trevarthen, 2008). In part, this self-integrating neural system operates independently of the neocortex (Merker, 2005, 2006); when neocortical refinements of perception and skill in movement and knowledge are being acquired and become active in guiding behavior, they are integrated with the subcortical orientations and emotional assessments. In short, emotions play a creative role in the regulation and development of an individual’s cognitions and learning throughout life.

The fetal brain is already built as “intentional” in this experience-seeking sense, and the lifetime integrity of the self depends on this intentionality (Zoia et al., 2007). The mind of a fetus, though lacking all experience of the world and all rationality, has a clearly marked latent power to be both an intentional agent and a person who must relate to other persons. From their first appearance, movements of the body exhibit an intrinsic motive pulse (IMP) that is expressive—the rates of motor rhythms vary with the intensity of effort and with the “confidence” or anticipated experiences associated with the intentions to perform actions (Trevarthen, 1999). The core integrative and regulatory systems of the brain constitute the motivated self and define the functions of its consciousness and their emotional regulation and development (Panksepp, 2001; Merker, 2005, 2006).

FIGURE 3.2

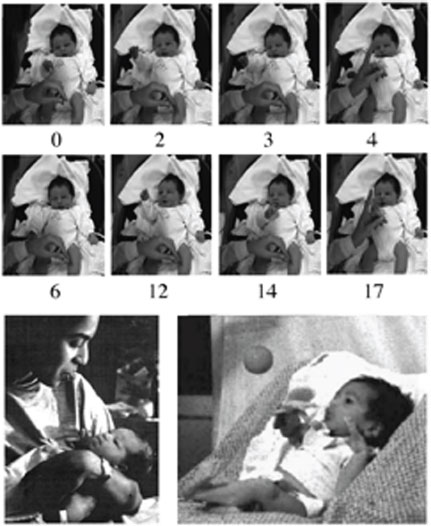

Manifestations in newborn infants of conscious interest in persons, seeking to engage with their expressions. Above: Photographs from video made by Dr. Emese Nagy, who studies neonatal imitation, of an infant less than 2 days old in a hospital in Hungary. The infant first watches its own hand (1 to 3), then attends as E. N. presents her index finger (4), the infant waits, then raises its hand and looks at it (12), then partly extends an index finger to imitate while looking intently at E. N. (14). E. N. is provoked to repeat her movement while the infant watches the finger intently (17). (The numbers mark seconds after the beginning at 0). Below: An infant 30 minutes old imitates tongue protrusion. Another, also 30 minutes after birth, follows a ball being moved playfully by a person. The infant tracks the animate movement with eyes, mouth, hands, and one foot (Photos by Kevan Bundell).

Emotions as Visceral and Motor Regulators of the Self,

Relationships, and Communities

The life-sustaining activities of the autonomic nervous system (ANS), which begin in the human embryo weeks before the cerebral cortex cells appear, take responsibility for maintaining the “internal environment”—regulating blood chemistry, circulation, respiration, digestion, and the immune system responses. These activities have also evolved to sustain the vitality of the social organism.

The parasympathetic nerves of the ANS in humans include special visceral efferents of the head—of cranial nerves 3, 7, 9, and 10, which, assisted by nerves 4, 5, 6, 11, and 12, not only regulate looking and seeing, blood circulation, breathing and respiration, eating, digestion, and excretion, but also express emotions that control social contacts and relations (Porges, 1997). All the muscles of human communication—of the eyes, face, mouth, vocal system, head, and neck—which are constantly active in conversation expressing emotions and thoughts, and which have disproportionately large representation in the sensory and motor “maps” of the neocortex, receive excitation from these cranial nerves (Aitken & Trevarthen, 1997; Trevarthen, 2001b). The activities of sympathetic and parasympathetic neurons are made evident for the benefit of social partners in specially adapted states of emotional expression (Panksepp, 1998; see also Porges, Chapter 2, this volume).

In a momentous evolutionary step, human hands, in addition to their extraordinary dexterity in manipulation, have become associated with the above organs of communication as supremely adaptable organs of gestural communication, capable of conveying sensitive interpersonal feelings by touch and rhythmic caresses, as well as of acquiring a language ability equal to that of speech (Trevarthen, 1986). Infants can imitate not only expressive forms of vocalizations and facial movements (e.g., tongue protrusion), but also isolated and apparently arbitrary gestures of the hands (e.g., index finger extension; see Figure 3.2), and they use them to establish an intersubjective engagement regulated by emotions (Kugiumutzakis, 1998; Nagy, 2008).

The movements of the infant’s voice, face, and hands, are adapted for interpersonal transmission of impulses to know and do in dialogue, and all are potent vehicles for the communication of emotions and states of sympathetic motivation. The graphic hand movements of a young infant that, like the accompanying expressions of the face, show approach or withdrawal, pleasure, fear or anger, protection of the eyes or face, exploratory curiosity and surprise, are not learned. They are part of the innate emotional system for self-protection and for self–other communication.

Research on the subtle regulation of communication with infants has brought greater appreciation for the dynamic and expressive principles of nonverbal communication between human beings of all ages. The combined operation of visceral and somatic “mirror” reactions between mother and infant gives, in ways we do not fully understand, the infant means of expression and access to the other anticipatory “motor images” and “feelings” and permits direct motive-to-motive engagement with a companion as well as interest in a shared environment and what is being done in it. Thus arises the psychological phenomenon of intersubjectivity, which couples human brains in joint affect and cognition, and mediates all cultural learning (Trevarthen, 1998; Trevarthen & Aitken, 2001). A child must learn what other people know and do by intersubjective sympathy for their actions and their emotional qualities. How states of body and mind are shared has become an active new field of enquiry in phenomenological psychology and philosophy (Zlatev et al., 2008).

How Developmental Changes in Motives

Determine Cultural Learning

Internally generated age-related changes in what infants prefer to do and in what interests them are evidently adapted to regulate adult attentions, as well as to regulate infants’ own developing consciousness and experience (Trevarthen & Aitken, 2003). Some emotional expressions and reactions of infants are obviously related to eliciting maternal care and protection for the body. These can be called emotions of attachment. But other more complex innate emotions are adapted to promote sharing of actions and experiences, and for expressing evaluations of objects located and identified by the infant’s intentions or desires—that is, by the infant’s mind. These are emotions of companionship that control the cooperative quality of activities and interests in friendship with identified persons (Trevarthen, 2001a, 2005b). These emotions show regular age-related changes through infancy. They define cooperative interests in the shared world and enable the child to be educated in socially shared meanings, knowledge, and skills. They are the human emotions of cultural learning.

John Bowlby (1988) formulated attachment theory with support from ethological evidence of the effects of maternal deprivation in rhesus monkeys. Early body contact plays a critical role in the development of appropriate social behavior, and disruption of early contact results in stress and later pathological behavior. Research on newborn rodents, cats, and primates shows that their rapidly developing brains depend on parental support. The quality of parental support determines how the brain will grow, and neglect or stress can damage the brain (Schore, 1994).

We are born more immature than other primates, with sensitivity to the emotions of persons who offer intimate attention with their whole body (Brazelton, 1979; Brazelton & Nugent, 1995). Adults in states of distress or suffering from illness or aging have a comparable need for affectionate and sensitive response.

Young infants respond with exquisite sensitivity to the touch, movement, smell, temperature, etc., of a mother. Newborns gain regulation from the rhythms of maternal breathing and heart beat, and fetuses are sensitive to maternal vocal patterns (Fifer & Moon, 1995). Infants’ arousal and expressions of distress are immediately responsive to stimulation from breastfeeding. These interactions are not merely physiological. For example, the response to breast milk is facilitated if the newborn has sight of the mother’s eyes. The newborn infant is ready to perceive and respond to the interest of her eyes and to respond to her oral expressions of emotion. The communicative precocity of human newborns indicates that emotional responses to caregivers must play a crucial role in early brain development (Schore, 1994). Indeed, the infant’s endocrine status, neurochemistry, and brain growth respond to maternal stimulation, which cannot be fully substituted by artificial clinical procedures; this responsiveness can be demonstrated to a new mother and father so that they can provide sympathetic, loving attention that will help the baby’s “social brain” grow (Panksepp, 2007).

Remarkable evidence that this precocious interpersonal sensitivity includes interest in sharing new ideas comes from research that shows us how, and for what purpose, newborns imitate (Nagy & Molnàr, 2004). If the procedures a researcher uses are not merely enacted to elicit responses, but are administered at intervals in attentive and “respectful,” ways, it becomes evident that a newborn baby is not only capable of imitating single arbitrary gestures, such as tongue protrusion, extension of an index finger or two fingers, or a firm closing of the eyes (see Figure 3.2). Given an opportunity by a waiting partner, the infant is interested in eliciting or initiating an imitation by repeating such a movement as a provocation, seeking a response. Moreover, these complementary actions are accompanied by different autonomic or emotional states of self-regulation. Synchronous with imitating, the newborn shows a heart acceleration, and when the infant makes a provocative movement attending to the other person to receive his or her response, the heart decelerates. This reciprocity of emotional regulation makes possible the intense cooperation in experience on which all human cultural enterprise depends (Trevarthen, 2005a).

Prefrontal “mirror neurons” have been taken as possible candidates for the mechanism that enables infants to imitate, to associate emotion with imitation of others’ movements, and to develop language (Rizzolatti & Arbib, 1998; Gallese, 2005). However, given the relative immaturity of the frontal cortex in infants, it is more likely that unidentified subcortical components of a “mirror system” are involved in many imitations that neonates perform. The Mirroring of actions involves multimodal or transmodal sensory recognition of intentions in movements by many regions of the cortex; moreover there are many multimodal, affect-regulating neural populations in the brainstem. These are integrated within extensive systems that formulate motor images for action and expression (Damasio, 1999; Holstege et al., 1996; Panksepp, 1998). The distribution of activity in the brain of an infant a few weeks old when giving attention to a picture of a woman’s face, indicates that the “sympathy system” of intersubjective communication (Decety & Chaminade, 2003) is well formed when the baby is born (Tzourio-Mazoyer et al., 2002).

A Map of Three Complementary Uses of Human Motives and Emotions, and Two Kinds of Ritual for Collective Action with Others

Ways of Acting with a Human Body and Steps to Share

Meaning before Language

We can distinguish three ways in which the prospects of the mind are made effective in the service of life as a social being—three worlds in which the animal self or psyche seeks to move well—that is, to engage in action that is effective and has efficient prospective control (Trevarthen, 2001a; Trevarthen et al., 2006): (1) The well-being of the body of the self is sustained by the brain in cooperation with the hormonal systems that control distribution of vital resources and the economy of energy which, in turn, sustain the whole organism in health. (2) Engagements of the self with the physical world must be directed subjectively, by intentions that perceive objects and events and how their substances and other properties and processes can be used. (3) In communication with an other, or conscious subject, there is an additional need to be able to detect the probable reactions of that other, intersubjectively. Communication of emotions is required to negotiate any cooperation in purposes and experiences with an other (see Figure 3.3).

FIGURE 3.3

An infant is born with these three regulations, but the motives that integrate control of actions and experiences change greatly as the child’s body and mind grow, transforming the ways in which the self functions in the body, with objects, and in the world of people. We can distinguish two paths available to the child that, if all goes well, lead to enthusiastic and practical life in society. These correspond to the two kinds of ritual by which communal life was celebrated and regulated in ancient Greece: the rites honoring the gods Apollo and Dionysos. Each gives the body and mind different tasks, and each has its own emotions. The reasoned Apollonian regulation of dealing with mastery of the physical world, practically, technically, and scientifically, differs from the Dionysian love and exuberance of the body in human company, which releases pleasurable energy of action and imagination as cultivated in the arts.

Enthusiasm, literally meaning a state of “having the gods within,” motivates adventurous action of all kinds. Its purposes can be ordered practically, with studied reference to physical reality that sets limits to movement and offers ways by which projects can be carried out in a world that may be ordered by human-made structures and procedures or rituals. Or the enthusiasm for acting can be guided in more self-aware and passionate ways and by sympathetic respect for the wishes and feelings of others, and for the pleasures they gain from moving and sharing movement in creative artistic ways. All cultural rituals, practices, and creations can benefit from both of these ways of being “inspired by the gods,” but the motivations of individuals differ. There is a tendency in ordered society for either science, technology, and commerce, on the one hand, or artistic creativity and the pursuit of beauty and pleasure of movement in spontaneous intimacy, on the other, to take precedence, thus distorting the social enterprise.

How Emotional Narratives Become the Discourse of Language

Early protoconversational engagements with infants, in the first 4 months, manifest the direct person-to-person emotional regulations of “primary in tersubjectivity” (Trevarthen, 1979). Protoconversations are succeeded by rhythmically structured “musical” games—first, person–person games with communication itself in ways that manifest the playfulness so evident among young mammals (see Figure 3.4), and then “person–person–object games” objects that attract the interest of the infant who is beginning to explore with the aid of hands and mouth. At 9 months, a change occurs that initiates “secondary intersubjectivity” (Trevarthen & Hubley, 1978). Now the baby is becoming interested in sharing the ways companions use objects, and he or she makes practiced movements to engage with the world of things. The baby’s willingness to cooperate in a task and to make “protolinguistic acts of meaning” (Halliday, 1975), transforms the ways in which parents speak to the infant. Questions and rhetorical comments are rapidly replaced by instructions, directives, and informative comments that the infant now attends to and tries to follow. This is the start of cultural information transfer between generations.

Research on communication with infants has clarified the innate and developing foundations of these playful behaviors, and, thus, of memory and meaning (Trevarthen & Aitken, 2001; Reddy, 2008). It has demonstrated how actions in real time are shared between persons of all ages, enabling them to collaborate in intersubjective and collective acting, remembering, and recalling. The nature of cultural learning and historically contrived “communities of meaning” and their languages depends upon these vital engagements of minds and bodies (Donald, 2001).

FIGURE 3.4

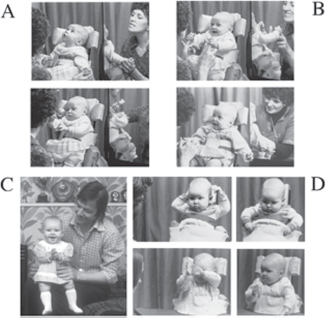

After 3 months, infants’ bodies become stronger and their consciousness is more complex. A: A 4-month-old infant is curious about the room and concentrates her attention on an object presented by her mother. B: When her mother starts a rhythmic body game, the baby is both intensely interested and pleased. At 5 months she is attentive and participates in a “ritual” action game, “Round and round the garden,” composed as a rhyming 4-line stanza with a lively iambic pulse. The infant has learned the song and vocalizes at the end in synchrony with the mother, matching her pitch. C: A 6-month-old sitting on her father’s knee smiles with pride as she responds to her mother’s request to show “Clappa-clappa-handies.” D: The same 6-month-old shows her uneasiness and withdrawal in front of two strangers, a man and a woman, who attempt to communicate in friendly but unfamiliar ways. The infant appears to experience shame as well as distress.

The key factors in language development are intersubjective or communal, not one-head rational. A child comes to understand and use words naturally in intersubjective, two-head relationships with older talkative companions, then with same-age friends, sharing imaginative journeys and projects. The psychological motives that make a human body move with inventive grace are infectious. We sense one another’s psychic states by a direct transfer: mind to body—body to mind. The rhythms and expressive alphabet of this communication, the music and dance of it, are brought to light by research on unconscious postures, gestures, intonations, and facial expressions of conversation (Fonagy, 2001), and especially from detailed analysis of how infants communicate, and how adults adjust their communication to meet young, unsophisticated minds (Reddy, 2008).

Observations made from home movies of infants under 1 year who, in the second or third year, were diagnosed as having autism spectrum disorder, indicate that the first or primary failing concerns these rhythms of attending and moving, and that this in turn causes problems with parental responses that can exacerbate the child’s developmental difficulties, further weakening their intersubjectivity (Trevarthen & Daniel, 2004; St. Clair et al., 2007; Aitken, 2008).

Rhythms of the Embodied Self and of Cooperation: Synchrony and Sympathy

All animal actions take the form of rhythmic or pulsing measured sequences of movement—regulated through time and across a great range of times, from minimal perceptible intervals to days, seasons, and lifetimes (Osborne, 2008; Trevarthen, 2008a). Brains are networks of dynamic systems all obedient to rhythms that flow in unison (Buzsaki, 2006), orchestrating their effective actions to fulfill future-sensitive (motivated) desires and to be capable of recollecting past experiences of being. Without the coordinated regulation of spontaneous neural activity through time, there is no other way all these muscles of my body can work in collaborative efficiency—imaging and executing their forces in synchrony and succession in the present moment, with respect for past achievements and difficulties, and in realistic appraisal of future prospects—modifying inclinations and desires for the future that are founded on experiences past. It takes a coherent sense of time. Moreover, there would be no way for me to sympathize with another person’s intentions and feelings if we could not share the rhythms of this self-synchrony to establish inter-synchrony (Condon & Ogston, 1966).

Cerebral representations of movement in time, anticipating reafferent stimulation, stimulation fed back from the moving body and its parts (preparations for which are established in the brain of a fetus), can explain the abilities of infants, even newborns, to produce rhythmic and melodic forms of movement that match the timing of adult movements, and to enter into a “dance” of synchronized, imitative, or complementary interactions with the adult (Beebe et al., 1985; Stern, 1971, 1999). These cerebral representations explain the sensitivity that young infants have to precisely controlled contingent stimulus effects of their own actions, the coordination they achieve between others’ movements and their own, and the distress that is caused when a partner’s movements (i.e., his or her actions and reactions) are noncontingent (Murray & Trevarthen, 1985; Nadel, et al., 1999).

The Communicative Artistry and Practical Technique of Human Emotions

Birds, whales, and gibbons have the motivation to communicate vocally by species-specific expressive displays shaped innately, or genetically. But they also learn the songs of their group, strengthening the community by keeping “traditions” alive in a transgenerational composition of songs (Brown, 2000; Payne, 2000; Merker, 2008). Sounds of the human voice have comparable functions and are also organized in narratives of aesthetic and moral feeling in the storytelling performances of song, the musicality of which can be imitated by instrumental music (Malloch & Trevarthen, 2008). “Tone of voice” (Fonagy, 2001) and the “vitality affects” of voice and gesture (Stern, 1993, 1999) determine the interpersonal effect of utterances, even in communication mediated by conventional signs or text of any kind (Brandt, 2008). Aesthetic or poetic principles influence the factual message, giving its story a “literary” coherence of motivation (Bruner, 1990; Turner, 1996; Fonagy, 2001; Kühl, 2007).

The dynamics of human emotion and their special adaptations for transmission of products of invention between individuals are richly displayed in the temporal or dramatic arts, especially song, music, and dance (Smith, 1777/1982). These cultivate the motivational base or inner subjective context that is alive in all rational thought and all culturally elaborated practices, techniques, and explanations. Human meanings and beliefs are made strong and given meaningful and memorable shape with the passionate support of musical, poetic, and prosodic forms of expression—that is, with “musical semantics” (Kühl, 2007). The social brains of children are nurtured by the musicality of communication with companions, adults, and peers.

How Primary Self–Other Regulation Leads to the Creation of Meaning

There are…two sides to the machinery involved in the development of nature. On the one side there is a given environment with organisms adapting themselves to it…The other side of the evolutionary machinery, the neglected side, is expressed by the word creativeness. The organisms can create their own environment. For this purpose the single organism is almost helpless. The adequate forces require societies of cooperating organisms. But with such cooperation and in proportion to the effort put forward, the environment has a plasticity which alters the whole ethical aspect of evolution.

—(Whitehead, 1929)

In a human community, individuals transform their relationship to the environment, their adaptation to its benefits and dangers, by the cooperative creation of a culture with its historically contrived rituals and beliefs, its techniques and arts, and its language. The foundations for this transmission of knowledge and skills across generations and hundreds and thousands of years, which gives humans a collective power over nature that Alfred North Whitehead claims changed “the whole ethical aspect of evolution,” is established in the development of every human body and brain. Infants are born motivated for cultural learning (Trevarthen & Aitken, 2003). These changes are associated with transformations of the emotional powers and needs of the child to which parents must adapt by changes in their “intuitive parenting” (Papoušek & Papoušek, 1987).

How Infants’ Emotions Grow with Responsive Parental Support

In the last 10 years, many findings have been made in support of the new concept of infants’ “innate intersubjectivity” (Trevarthen, 1998; Trevarthen & Aitken, 2001), which is accepted as building a coconsciousness that enables the child to achieve mastery of cultural learning and that provides the essential foundations for understanding and using language (Bråten & Trevarthen, 2007).

Using the idea that infants have innate motives to guide their life with others, we have charted four periods in the first year of life, marked by age-related changes in the capacities of the baby to regulate actions and awareness—periods in which the foundations of experience and the relationships with parental care are established and transformed (Trevarthen & Aitken, 2001, 2003). Step by step, the expectations of the baby are guided by new motives to move in new worlds. These steps on the way to meaning in life with others are separated by short periods of rapid change, during which the motives of the child are transforming from within, apparently generated by transformations in the brain, some of which have been identified (Trevarthen & Aitken, 2003). These periods of change correspond to the “touch points” that Brazelton (1993) has noted give parents an opportunity to discover new ways of intimately sharing life with their infants, and to foster development.

The fate of each step in development depends on the capacity of “intuitive parenting” to respond to the infant’s changing needs (Papoušek & Papoušek, 1987, 1997; Gomes-Pedro et al., 2002). If the mother of a baby is depressed and incapable of responding happily to the baby’s appetite for lively care and communication, this can cause problems in development of the infant’s self-confidence and understanding (Murray & Cooper, 1997; Robb, 1999; Marwick & Murray, 2008). Both the positive emotions in sensitive and mutually supportive communication and the negative emotions that disrupt communication in insecure or failing relationships can be related to their effects in the development of the child (see Figure 3.4). They also indicate various ways in which therapy can help when the individual is failing to cope, whether with self-or other-related difficulties.

As the infant becomes more active socially by 3 or 4 months, he or she can engage in playful encounters with siblings. It is particularly significant that by 6 months, the social emotions of pride and shame come online. The emotion of pride in performance of a learned ritual that is part of a favorite action, song, or game routinely shared with a parent is in contrast with manifestations of wariness, avoidance, and shame in an engagement with a stranger who not only looks and sounds unfamiliar, but who does not “know the game” (Trevarthen, 2002). This social sensitivity, regulated by the interpersonal “moral emotions” of pride and shame, becomes most evident just before a major transformation in the infant’s interests and emotions, for example, the transition to secondary intersubjectivity at 9 months, each of which has effects on the behavior of an attentive parent. If a parent is “attuned” to the eagerness of the infant to act in demonstrative ways and to have these self-conscious performances noticed and responded to with signs of pleasure and attentive admiration, and if the parent’s actions make him or her a part in the play, the child is manifestly happy and motivated to repeat the performance or, alternately, to create another diverting behavior (Reddy, 2008). Parents who respond with affection gently tease the infant and are quick to respond with humor to attempts of the infant to tease (Reddy & Trevarthen, 2004). Such behavior brings out the emotions of playfulness and focuses attention on rituals that may be learned as skills (Eckerdal & Merker, 2009).

A sad and detached mother is not a companion in playful invention of games. Furthermore, she may be insensitively stimulating or coercive, eliciting avoidance or protest (Gratier and Apter-Danon, 2008). Infants are equipped with defensive emotions that repel unsympathetic communication. These defensive emotions can further trouble the relationship and may be accompanied by stress that harms the infant’s motivations and limits learning. Forms of therapy that aid a mother to provide more sympathetic and playful response to her infant—for example, video interaction guidance (VIG), which selectively identifies and reinforces moments of positive contact, can evoke the mother’s pleasure in her infant and in the joy and pride that her child expresses (Schechter, 2004; Fukkink, 2008).

If the parents are available and in good humor, they find the infant a delightful, teasing playmate, and they share action games and nursery songs, which the infant quickly learns. Thus, many months before any awareness of the purposes of language or the ability to speak, a baby, if given the kind of affectionate support that comes naturally to happy parents, is becoming part of the musicality and ritual activities of a particular culture, enjoying appreciation by proud family members.

Testing the Time Sense and Emotional Quality of Engagement

Two kinds of perturbation or separation have been used to test the mutual emotional regulation of intersubjective contact between a mother and a young infant. This kind of research was necessary because there was, in the 1970s, strong theoretical denial that an infant just a month or 2 old could be capable of self-awareness, let alone awareness of an other, and capable of responsive, well-timed engagement motivated by purposes and emotions.

The first technique, implemented independently in the early 1970s by Ed Tronick et al. (1978) and Lynne Murray (Trevarthen, 1974, 1977; Trevarthen et al., 1981; Murray & Trevarthen, 1985), required a mother who was in the process of enjoying a protoconversation with a 2-month-old to stop being expressive and to hold her face immobile, with a neutral expression, in front of the baby for a minute. This “blank face” or “still face” procedure provoked an immediate response from the baby. First, the baby became attentive and sometimes made attempts by smiles, vocalizations, or gestures to appeal to or stimulate a response from the mother; then the baby became withdrawn, avoiding the mother’s gaze, with signs of distress and confusion. The baby looked depressed. This finding agreed with those from studies showing that infants of mothers suffering from postpartum depression could appear withdrawn and depressed and express themselves with a depressed vocal musicality (Field et al., 1988; Field, 1992; Murray and Cooper, 1997). Subsequent observations of infants with mothers who manifested a bipolar psychosis further indicated that a baby confronted with insensitive and repetitive stimulating behaviors makes efforts to compensate by being watchful, hyperactive, and having a “false cheerfulness” (Gratier & Apter-Danon, 2009).

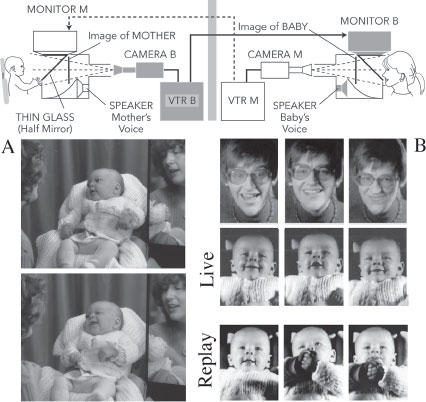

The second test, developed by Lynne Murray (Murray & Trevarthen, 1985) following experiments on mediation of communication with infants by television images by the Papoušeks (Papoušek & Papoušek, 1977), required that mother and 2-month-old should first engage in communication while in separate rooms by means of a two-way video–sound link, which proved not difficult for them to do (see Figure 3.5). Then a short segment of the mother’s happy communication was replayed to the baby. In this scenario the baby showed expressions of surprise, confusion, withdrawal, and sadness, much as occurs for the still-face procedure. This response proved that the infant was immediately sensitive to the “contingency” or live and sympathetic timing of the mother’s expressions. The communication had the right expressions in the right sequence but was out of synch with the infant’s behavior. This experiment has been replicated (Nadel et al., 1999). Further, the complementary test has been conducted in which the baby’s behavior in a live period of communication was replayed to the mother without warning (Murray & Trevarthen, 1986). The mother senses that “something is wrong,” but does not know what it is, and might blame herself for her baby’s apparent unresponsiveness. Human communication has to occur in real time, in all its creativity and unexpectedness, as in the improvisation of a jazz duet (Gratier & Trevarthen, 2008).

Conclusions: How the Roots of Emotional Communication May Be Restored

Detailed empirical research on the emotional behaviors of infants and young children in real-life situations where their motives are in active engagement with actions and expressions of others leads to an appreciation of the positive role of emotions in development and well-being in relationships (Donaldson, 1992; Nadel & Muir, 2005; Reddy, 2008). Emotions are organic or “live” processes that are “creative,” asserting their vibrant influence on emerging intentions, experiences, thoughts, expectations, and memories from birth and before. They should not, as A. N. Whitehead (1929) has said, be formulated as “products of logical discernment.” Scientific experimentation on the nature of emotions has, however, been guided by rational objective and causal explanations of the ways animals and people react to stimuli. It has adopted a “third person” position, measuring behavioral events in individuals from the point of view of an outside observer. It has supported a belief of industrialized Western cultures that a child’s negative or defensive emotions have to be “regulated” to keep them in balance and their pro-social feelings “developed” by a plan of training to inculcate culturally approved norms (Bierhoff, 2002). Support for a natural science of the whole range of relational emotions, one that follows a method of observation pioneered by Charles Darwin (1872), has come from neuroscience in recent decades (Panksepp, 1998, 2002, Chapter 2 this volume). Emotions are intrinsic principles that regulate adaptive life in the phenomenal world of movement—in relationships and communities, in commerce and politics, and especially in art.

FIGURE 3.5

Complex expressions of social engagement in co-consciousness between young infants and their mothers. A: A 6-week-old girl looks intently while her mother (seen in the mirror) speaks, then smiles as her mother pauses. B: Pictures from an engagement between an 8-week-old infant and her mother mediated by Double Television in an experiment by Lynne Murray. In the “live” condition, mother and daughter enjoy a “protoconversation” in which the infant is both highly expressive of many happy emotions, and tightly coordinated in time with her mother’s expressions and utterances. When the same 1 minute of the mother’s behaviour is “replayed,” the infant is immediately disturbed and becomes withdrawn and depressed. Infants are very sensitive to the contingency of a partner’s behaviours with their own.

The expressive/communicative activities and social customs that most directly represent the fluidity and creativity of human emotions are those of drama, music, and dance—naturally enjoyed ways of articulating and coordinating the limbs and self-regulatory organs of the body, coupling their tensions and impulses in rhythmic ways that seek to preserve energy and to channel it in most effective ways in obedience to an IMP. That communication between a mother and a young infant can be described accurately by a theory of “communicative musicality” is clear evidence of the source of human collaborative awareness in intimate creative expressions or a poetry (making) of stories. The notes, phrases, and evolving episodes of emotional narratives create and carry meaning, sustaining the rituals of culture (Gratier and Trevarthen, 2006; Malloch and Trevarthen, 2009).

The Message for Therapy and Education

Acting directly in response to the moral forces of relating evident in young children, taking note of the delight experienced in both directions, as from mother to infant and from infant to mother, has an importance that goes beyond what reason can explain or behavioral or cognitive training can achieve. Once a shared story is being written within the fun of its valued rituals, many meanings can be discovered and thought about with self-confidence and in confiding friendships. Rituals of teaching/learning and the “healing practices” to foster well-being in those who suffer from anger, fear, anxiety, and confusion depend not primarily on informational structures or “instruction” or on “training” of behaviors, but on sympathetic encouragement of the innate tendencies of all human beings—even the youngest or most debilitated—to share pleasures and to learn new meanings in nurturing company.

The therapist working with a person who has become confused by anxiety and fear and whose energy of enthusiasm has gone has a choice: try to make sense of the reasons and causes of the emotional loss, or try to seek, by sensitive provocation and positive belief, a form of appreciation that will evoke some signs of playfulness and hope for enjoyment in sharing the surprises of a human engagement in which there is no dislike or rivalry.

Infant research supports the use of nonverbal intersubjective therapies, such as music therapy, movement or dance therapy, drama therapy, pictorial art therapy, and body psychotherapy because these approaches accept that we are all equipped with a sensitivity for movement and qualities in movement, not only in our own bodies but in the bodies of others we touch, see, and hear. Moreover, “art therapies” have the benefit of accepting the assumption that we are story-making creatures, and that our own autobiography, and its main supportive characters, is the story that affects us most deeply.

Work with abused and emotionally disturbed children, or those with a constitutional disorder such as autism or Rett’s disorder, demonstrates the need in therapy or special education for communication at an intimate emotional level (Malloch & Trevarthen, 2008), whatever procedures are put in place in the routines of experience or the layout of environmental affordances and contingencies by training programs. Training in how to regulate life for the self and with other persons has beneficial effects only if the communication—the process of sympathetic intersubjectivity by which it is implemented—is good.

From his own practice and from observing the benefits of skilled therapeutic work of others, Dan Hughes (2006) has identified the primary principles of engagement and reconstruction in his dyadic developmental psychotherapy, as follows. Here Katie is an abused child, now about 8 years old, Jackie is her principal adoptive parent, and Alison is the therapist. All these characters are fictional, based on Hughes’s experience of many cases.

The psychological treatment of Katie…involved providing her with a series of complex integrative affective and reflective experiences. The central features of her treatment involved intersubjective affective experiences of both attunement as well as shame reduction…. Within [an] atmosphere of trust, Allison and Jakie employed empathy and curiosity, always grounded on acceptance, to explore with Katie various experiences of shame from her past and present life. Shame-reduction occurred by bringing the incident to Katie’s awareness, actively communicating empathy for her distress, and then through co-creating the meaning of Katie’s new affective and reflective states. This enabled her to integrate her fragmented self, increase her sense of self-worth, and enhance her ability to develop attachment security with Jackie. When Alison sensed and was responsive to Katie’s affective states, she provided her with both primary and secondary intersubjective experiences. The experience was most therapeutic when it occurred in a manner that involved eye contact, facial expressiveness, rich and varied voice modifications, and a wide range of gestures and movements. Allison’s voice moved easily from loud to soft, rapid to slow, with periodic long latencies in which she and Katie were wondering about a problem and its solution. Alison giggled and laughed, moved her face close and pulled away and demonstrated empathic sadness, fear or anger, closely attuned with Katie’s affective state quite readily in her facial and vocal expressions. While exploring the immediate interaction as well as a recent or distant event, she sat close to Katie and frequently touched her. Such physical contact greatly facilitated the communication and shared affect. Physical contact was as effective as voice tone and facial gestures in co-regulating various emotional themes of joy, excitement, shame, anger, sadness and anxiety. (p. 279)

The same principles of enhanced intimacy and sustained attention to the other are important for helping children with autism or other developmental disorders. Furthermore, being in touch with the deepest sources of emotional expression is necessary to open communication with very senile people and in those with severe mental handicaps (Zeedyk, 2008).

Therapists seek to change the feelings that affect their patients’ experiences so as to make them more confident, better able to adapt to life situations and relationships, and happier. To do so, they must find ways to engage with the motives that light up body and mind with emotions. Thus, they must move with the patient in the performance of real desired projects and tasks, not only tasks that exist as stories in talking. The rhythmic expressive foundation of emotional dynamics is the same for all spoken and unspoken “dances” of the mind. Emotions are how we dance together and doing so is at the heart of the human enterprise.