8

Emotion, Mindfulness, and Movement

Expanding the Regulatory Boundaries of the Window of Affect Tolerance

Pat Ogden

IN RECENT YEARS psychotherapy has begun to shift its emphasis from models of cognitive development to the “primacy of affect” in an intersubjective context, redefining psychotherapy as the “affect communicating cure” rather than the “talking cure” (Schore & Schore, 2008). Affect regulation and emotional processes are highlighted as central to psychopathology and thus to psychotherapy practice (Dorpat, 2001; Fosha, 2000; Goleman, 1995; Schore & Schore, 2008). Most current treatment models emphasize the resolution of unresolved emotions of painful past experiences and the expansion of the affect array. Therefore, prime targets of therapeutic intervention include a wide range of dysregulated and/or unintegrated emotions. The patient has often warded off these emotions, perceiving them as overwhelming, frightening, or too intense, until, within the context of an attuned therapeutic dyad, they are engaged, regulated, explored, fully experienced, and transformed.

That said, a direct, exclusive, or even primary focus on emotional processing can initially present difficulties in working with those patients who typically experience an overwhelming flood of emotions, a lack of emotion, or the same emotion over and over. Direct attention to emotions in such instances may exacerbate dysregulation and/or reinforce maladaptive emotional patterns. Affect might be best regulated, rather, through an exclusive focus on bottom-up or sensorimotor processing interventions that challenge these tendencies, promote stabilization, and pave the way for future efficacious processing of emotions. As we shall see, such sensorimotor processing interventions go beyond simple body awareness interventions (“What do you notice in your body? How do you experience that in your body?”) by using body sensation and movement to address and change how information is processed on a bodily level (“Follow that sensation of tingling: what happens next in your body? Feel the tension in your shoulder…sense the movement that wants to happen there; what happens as you slowly execute that movement?”).

From the specific vantage of an approach that privileges the regulation and processing of sensorimotor experiences, as such, this chapter explores the nature of procedural learning, trauma-and attachment-related issues, and the interface between emotions and the body, clarifying when and how to emphasize sensorimotor processing, when to emphasize emotional processing, and how to integrate the two. The use of directed mindfulness to work with procedural tendencies and to both deepen and enhance emotional processing is highlighted as well. I discuss theory and technique for working at the regulatory boundaries of the window of affect tolerance, as the patient’s arousal, both emotional and physiological, begins to challenge his or her integrative capacity, and I include an exploration of play and positive affect.

Procedurally Learned Physical Tendencies

Procedural learning involves the learning of processes—the “how” rather than the “what” or “why.” Commencing in infancy (Tulving & Schacter, 1990), procedural habits are formed gradually and incrementally as certain reactions to particular internal or external stimuli are engaged repeatedly over time. Once learned, these procedural internal actions (those that often cannot be observed: cognitive, emotional, and some physiological) and external actions (those that can be observed: physical and behavioral) are reliable and enduring. For example, skills such as riding a bike persevere over time and typically do not significantly diminish with disuse; similarly, tendencies such as the experience of shame, accompanied by physical tightening and withdrawing in the face of criticism, also persist long after the situations that originally elicited these reactions are over.

As powerful determinants of current actions, procedural learning encompasses habitual responses, skills, and conditioned behaviors (Schacter, 1996) formed by repeated iterations of movements, perceptions, cognitions, and emotions (Grigsby & Stevens, 2000). Although many kinds of actions that are procedurally learned can be initiated voluntarily (e.g., as tying one’s shoes), procedural learning does not “require conscious or unconscious mental representations, images, motivations or ideas to operate” (Grigsby & Stevens, 2000, p. 316). It is characterized by automatic, reflexive performance, becoming an even more potent influence because of its relative lack of verbal articulation, thus rendering most procedural behavior unavailable for thoughtful reflection.

Stimulus-related procedurally learned tendencies—that is, tendencies to respond automatically (on cognitive, emotional, and sensorimotor levels) and in characteristic ways to particular conditions—foster an anticipation of actions that were adaptive in the past long after environmental conditions have changed. A patient who was sexually abused by her father remained chronically tense in childhood in expectation of abuse; as an adult, the muscular tension remained, a physical tendency that was exacerbated at the thought of an intimate relationship, and which contributed to her chronic sense of impending danger and affect dysregulation. Aggravated by internal and environmental reminders of the past, such tendencies take precedence when other actions would prove more adaptive to current reality. Although this same patient desperately longed for a mate, her muscular tension and accompanying fear precluded the openness and trust necessary to pursue an intimate relationship.

Procedurally learned physical tendencies can be viewed as “a statement of…psychobiological history and current psychobiological functioning” (Smith, 1985, p. 70) that complements and corresponds with emotional tendencies. Formed to help us cope with early trauma and maximize the resources of our attachment relationships, these actions are initially adaptive, but over time become habits that are often maladaptive for current situations. They manifest as either primarily trauma-related or primarily attachment-related tendencies. Trauma-related tendencies stem from overwhelming experiences that cannot be integrated and typically solicit subcortical animal defensive mechanisms and dysregulated arousal. Maladpative attachment-related tendencies stem from experiences with early childhood caregivers that caused emotional distress but that did not overwhelm the child. Attachment trauma ensues when these experiences are overwhelming and perceived as dangerous, such that animal defensive responses and extreme or prolonged dysregulation ensue. Although maladaptive attachment tendencies and trauma-related tendencies are interconnected experiences that mutually influence each other and cannot be teased apart in actuality, recognizing the primary indicators of each helps clinicians prioritize emotional or physical tendencies pertaining to either trauma or attachment. These clinical choices become paramount in an integrative therapeutic approach.

Trauma-Related Physical Tendencies

Trauma, as defined here, refers to exposure to events that represent a real or perceived threat to safety and/or existence and thus elicit subcortical mammalian, or animal, defenses that are not mediated by the cortex; in fact, they actually disable cortical activity when engaged. These defenses can be loosely categorized into three general subsystems, all of which arose as ways of preserving survival: (1) relation-seeking actions, (2) mobilizing defenses that organize overt action, and (3) immobilizing defenses that engender a lack of physical action.

RELATION-SEEKING ACTIONS

Relation-seeking actions include behaviors relating to the attachment system, such as the “attachment cry” that is instinctively stimulated in children when they feel distressed, and is also activated in adults in times of stress and threat. The attachment cry, designed to elicit the help and protection of an attachment figure, is to be distinguished from attachment-related actions designed to secure and maintain enduring relationships. Underlying attachment is the “social engagement system,” mediated by the ventral parasympathetic branch of the vagus nerve, a relation-seeking system that fosters interaction with the environment (Porges, 1995, 2001a, 2001b, 2004, 2006a; cf. Chapter 2, this volume) because it governs parts of the body used in relational contexts: eyelid opening (e.g., looking), facial muscles (e.g., emotional expression), middle ear muscles (e.g., extracting human voice from background noise), laryngeal and pharyngeal muscles (e.g., prosody), and head tilting and turning muscles (e.g., social gesture and orientation) (Porges, 2003, p. 35).

Social engagement can also sometimes manage, modulate, and even disarm or neutralize an interpersonal threat, as illustrated by a patient’s appeal to a perpetrator’s empathy by “talking him down,” thus activating his social engagement system and deactivating fight and predatory actions. This is a complex, sophisticated action that requires some ability to either dissociate one’s own mammalian defenses temporarily or to override them consciously, whereas the attachment cry is a more primitive, basic defensive response that does not require interaction with the source of threat.

MOBILIZING DEFENSES

If relational strategies fail to ensure safety, the mobilizing defenses of fight or flight mediated by the sympathetic nervous system are engaged. Blood flow to large muscle groups is increased to prepare the body to take strong overt actions to ensure survival. When escape seems possible, flight is the instinctive defense of choice (Fanselow & Lester 1988; Nijenhuis et al., 1998; Nijenhuis et al., 1999) and can be conceptualized as both running away from danger and running toward safety. When aggression appears likely to be effective or when the victim feels trapped, the fight response is typically provoked. In addition to these instinctive defenses of fight and flight, mobilizing defenses can also include procedurally learned actions such as those used to operate a motor vehicle, which involve a complexity of automatic movements (e.g., turning the steering wheel, pressing the brakes) that can be executed without thought in the event of a potential accident.

IMMOBILIZING DEFENSES

When mobilizing defenses prove ineffective or maladaptive, such as in instances when a fight response might provoke more violence from the perpetrator or when the perpetrator and attachment figure are one and the same, passive avoidance or immobilization behaviors are the only remaining survival strategies (Allen, 2001; Misslin, 2003; Nijenhuis et al., 1998; Nijenhuis et al., 1999; Rivers, 1920; Schore, 2007). There seem to be at least three types of immobilizing defenses: (1) the sympathetically mediated freeze response (alert immobility), (2) the parasympathetically mediated feigned death response (floppy immobility), and (3) submissive behavior.

• Alert immobility. The freeze response is characterized by a highly engaged sympathetic system, possibly combined with arousal of the parasympathetic (dorsal vagal) system (Siegel, 1999); stiff, tense muscles; increased heart rate; and a feeling of paralysis coupled with hyper attentiveness. This “alert immobility” (Misslin, 2003, p. 58) may appear as complete stillness except for eye movement and respiration.

• Floppy immobility. “Feigned death” or “floppy immobility” (Lewis et al., 2004) is powered by the parasympathetic dorsal branch of the vagus nerve. Characterized by limp musculature, behavioral shutdown, slowed heart rate, and/or fainting (Lewis et al., 2004; Porges, 2001a, 2004, 2005; Nijenhuis et al., 1998, 1999; Scaer, 2001; Schore, 2007), this defense variant occurs as a “last resort” when all else has failed. With profound inhibition of motor activity (Misslin, 2003), coupled with little or no sympathetic arousal, this hypoaroused condition is a shutdown state that reduces engagement with the environment and may be accompanied by anesthesia, analgesia, and muscular–skeletal retardation (Krystal, 1988; Nijenhuis et al., 1999).

• Submissive behaviors. This type of passive avoidance “aim[s] at preventing or interrupting aggressive reactions” (Misslin, 2003, p. 59). Characterized by movements such as avoiding eye contact or lowering the eyes, crouching, and bowing the back before the perpetrator, submissive behaviors may include an automatic obedience to the demands of the aggressor. Such behavior is often characterized by a mechanistic compliance or “robotization” (Krystal, 1978) and usually involves a lack of protest against abuse (Herman, 1992).

These mammalian defensive strategies are designed to increase safety and assure survival. However, they become liabilities when they are used repeatedly and automatically, because they turn into inflexible procedural tendencies rather than adaptive responses to immediate threat. Traumatized individuals tend to experience reminders of past trauma as indicating current danger, which sets off these bottom-up animal defensive subsystems again and again. Eventually, they become default behaviors over other, more adaptive actions. For example, habitual submissive behaviors, characterized by mechanistic obedience, can lead victims to respond to perceived threat with resignation, compliance, and acquiescence. One patient repeatedly allowed a relative who was her childhood perpetrator into her home, knowing that abuse would follow. Children whose dorsal vagal tone increased as the only defensive option to childhood abuse tend to become easily hypoaroused as adults, often characterized by a slumped, collapsed posture and/or flaccidity in the musculature. Action tendencies related to freeze are characterized by muscular tension and “agitated immobility” and typically include a “chronic state of hypervigilance, a tendency to startle, and occasionally panic” (Krystal, 1988, p. 161).

Habitual engagement of mobilizing defenses of fight, flight, and relation-seeking actions also impair adaptive functioning. These active defenses are invariably accompanied by hyperarousal and muscular constriction. Patients with a tendency toward “fight” responses typically report tension in the arms, shoulders, jaw, and back; patients with reliance on relation-seeking actions tend to overuse clinging and proximity-seeking behaviors; patients with dysregulated flight responses often exhibit fleeing behaviors, such as precipitously leaving social situations or the therapist’s office or running away, as well as subtler flight actions such as turning, twisting, ducking imaginary objects, or backing away. For example, a patient who witnessed the collapse of the World Trade Centers afterward found herself beginning to run for cover whenever she heard a plane overhead.

For patients with dissociative disorders, these animal defensive strategies may manifest as discrete “parts” of the self, each with its own particular somatic tendencies (Ogden et al., 2006; van der Hart et al., 2006). One patient, after years of therapy, explained, “This [the tension and angry thrust of her jaw] is the part that fights, and this [the collapse in her spine and loss of energy in her arms] is the part that submits, and when I don’t even feel my body, that is the part that just isn’t there any more.” In therapy, this patent initially reported feelings of “going crazy,” reflecting an inability to understand her internal dissociative system and the adaptive function of the animal defensive responses gone awry in her current nonthreatening context. As for most patients, it was important for her to learn through therapy that, even though not adaptive in her current life, each animal defensive response was adaptive at the time of the abuse. It is not the defensive responses themselves but their over-activity and inflexibility that contribute to chronic affect dysregulation and pathology in traumatized individuals.

Attachment-Related Physical Tendencies

Early relational dynamics are the blueprints for the child’s developing cognition, affect array, regulatory ability, and physical tendencies (e.g., the way the child learns to move, hold his or her body, and engage particular gestures and facial expressions). From interactions with attachment figures, the child forms internal working models (Bowlby, 1988) that are encoded in procedural memory and become nonconscious strategies of affect regulation (Schore, 1994) and relational interaction. Both attachment-and trauma-related issues ensue from traumatogenic environments where the attachment figure and perpetrator are one and the same, but attachment-related issues also stem from non-life-threatening childhood experiences with caregivers (e.g., inadequate parental attention; harsh, inconsistent, insensitive, or fault-finding parenting) that cause emotional distress but are not perceived by the child as physically dangerous or life threatening.

When an attachment relationship has induced negative emotions and negative cognitions, physical tendencies also ensue, preventing integrated, free-flowing, spontaneous movement. For example:

If a child grows up in a family that values high achievement and is encouraged to “try harder” at everything she undertakes, her body will shape its posture, gesture, and movement around this influence. If this value is held at the expense of other values, such as “you are loved for yourself, not for what you do,” the child’s musculature will probably be toned and tense. The body will be mobilized to “try harder.” A child who grows up in an environment where trying hard is either discouraged or maladaptive, and where everything she achieves is undervalued, might have a sunken chest, limp arms, and shallow breath reflecting a childhood experience of not feeling assertive and confident, of “giving up.” It may be difficult for this child to mobilize consistent energy or sufficient self-confidence to complete a difficult task. (Ogden et al., 2006, p. 10)

These physical tendencies in turn reinforce chronic negative emotions and cognitive distortions and constrict affect array, whereas an aligned, erect, but relaxed posture, full breathing, and supple tonicity support adaptive affect regulation and array and a positive sense of self.

The physical tendencies of secure and insecure childhood attachment histories are visible in our adult patients. Adults who are securely/autonomously attached demonstrate the capacity to interactively regulate (Schore, 1994), reflected in context-appropriate physical action tendencies that enable seeking suitable contact and proximity to others: reaching out, moving toward and away, and setting adaptive boundaries. These tendencies reflect a capacity to ask for and use help when their own capacities are ineffective or overwhelmed (Fosha, Paivio, Gleiser, & Ford, 2009; Ogden et al., 2006; Schore, 1994). Additionally, these individuals are able to utilize autoregulatory strategies independent of relational contexts, which manifest in physical tendencies such as full breathing, grounding (being aware of the legs and feet, their weight, and their connection to the ground) and centering (being aware of the core of their body and their bodily sense of self).

People with insecure-avoidant attachment histories routinely shun situations that stimulate attachment needs and prefer to autoregulate under stress by withdrawing from others. Often becoming uncomfortable, awkward, or even dysregulated when executing simple actions such as reaching out with the arms and moving toward others, they may find pushing-away motions more familiar and less disturbing. Joey had grown up “tough” with an alcoholic father who could abide no weakness in his son. During the course of therapy, I asked Joey to experiment by simply reaching out with his arm as if to reach for another person. He said that he immediately wanted to “back away,” and that he would rather push out than reach out. When he eventually did reach out, he said, “This feels like jumping off a cliff; I don’t know how to do this,” and his body mirrored his words in its tension, slight leaning back, stiff movement of his arm, reaching with locked elbow, palm down. His non-verbal bodily message was that he was uncomfortable and did not expect a safe, empathic reception.

Others with avoidant histories may experience low autonomic arousal as well as decreased muscular tonicity, finding it easier to passively withdraw than take action that would promote interactions with others (Cozolino, 2002). Jeanie said that relationships were “for other people,” not for her. When she explored reaching out in therapy, her body drooped and her reaching was partial and weak. She failed to extend her arm fully—her elbow remained pinned to her side—and the gesture lacked energy and conviction. She said, “What is the point? No one will respond.” The lack of tonicity and vitality in the act of reaching echoed her words: Both reflected a paucity of empathic parental attention and care.

These avoidant patterns contrast with those of patients with insecure-ambivalent histories, who typically have a tendency toward enmeshment, clinging behavior, and increased affect and bodily agitation at the threat of separation from an attachment figure. Usually quite comfortable with reaching out, such patients may experience intolerance for distance corresponding with a tendency to cling, grasp, and a failure to literally “let go.” When Carmen experimented with reaching, she leaned forward eagerly, reaching out toward her therapist with a full extension of her arm, taking a step forward as she did so. Preoccupied with the emotional and physical availability of her therapist, she said she wanted to move even closer and became agitated and irritated when her therapist instead suggested she might explore reaching out from increased distance, interpreting the suggestion as indicative of her therapist’s unavailability.

When the attachment figure is also a threat to the child, a confusing and contradictory set of behaviors ensues that can be conceptualized as the result of simultaneous or alternating stimulation of attachment and defense systems (Lyons-Ruth & Jacobvitz, 1999; Main & Morgan, 1996; Steele, van der Hart, & Nijenhuis, 2001; van der Hart et al., 2006). When the attachment system is stimulated, the individual instinctively seeks proximity and engagement, but during proximity, which is perceived to be threatening, the defensive subsystems of flight, fight, freeze, hypoarousal/feigned death, or submissive behaviors are mobilized. Therapists may be baffled by the paradoxical responses of their patients to relational contact. For example:

Lisa frequently complained that “no one is there for me” and begged her therapist for more contact: to sit closer, to hold her hand if she cried, to call to see how she felt during the week. Yet, in sessions, Lisa consistently seated herself in such a way that she was facing away from the therapist and orienting toward the floor and sofa, and her body stiffened when the therapist moved her chair closer at Lisa’s request. Proximity-seeking emerged in her verbal communication, while avoidance was communicated physically: Her body held back the approach, avoiding even eye contact. (Ogden et al., 2006, p. 53)

Lisa, like most patients with unresolved attachment trauma, was torn between her desperate need for relationship and her profound fear of it. Lisa had a mother who was a source of safety and comfort but who also tended to have fits of rage, during which she would vent her anger toward Lisa in physical and emotional abuse. Over time, Lisa’s ability for adaptive emotional regulation and social engagement were sacrificed as sympathetic (i.e., mobilization) or dorsal vagal (i.e., immobilization) defenses predominated over ventral vagal tone (i.e., social engagement), and her postures and gestures associated with fear blended with and contradicted those physical movements of seeking relationship.

Emotions and the Body

Both trauma-and/or attachment-related physical tendencies influence, and are influenced by, emotion. Neuroscience has taught us that emotions and the body are mutually dependent and inseparable in terms of function (Damasio, 1994; Frijda, 1986, LeDoux, 1996; Schore, 1994). Darwin (1859/1897) proposed that emotional responses themselves comprise a set of postures and other motor behaviors that may denote an immediate emotional response to current stimuli or a habitual, chronic emotional state relevant to the past but triggered by current conditions. Damasio (1994, 1999) pointed out that emotions have two somatic components: interoception and expression. Interoception is usually invisible to others, being experienced as an internal subjective awareness as the sensory nerve receptors (interoceptors) receive and transmit sensations from stimuli within the body. The “primary emotional [sensations] reflect the non-verbal sensation of shifts in the flow of activation and deactivation—the flow of energy and evaluations of information—through the system’s changing states” (Siegel, 1999, p. 125). In contrast, postures, facial expressions, and gestures outwardly express internal emotional states, communicating these states to others. Finally, emotions are commonly described as critical motivators of action, signals that orient us to important environmental stimuli (Krystal, 1978; van der Kolk et al., 1996) and serve as “drives or deterrents for most of our actions” (Llinas, 2001, p. 155).

However, both action and interoception are also precursors to, and to some degree, determinants of, emotion. A variety of studies demonstrates the impact of posture and other movements on the experience, interpretation, and expression of emotion. Subjects who received good news in a posture in which the spine was slumped reported feeling less proud than subjects who received the same news in a posture in which the spine was upright (Stepper & Strack, 1993). Schnall and Laird (2003) showed that subjects who practiced postures and facial expressions associated with sadness, happiness, or anger were more likely to recall past events that contained a similar emotional valence as that of the one they had rehearsed, even though they were no longer practicing the posture. Similarly, Dijkstra, Kaschak, and Zwann (2006) demonstrated that when subjects embodied a particular posture, they were likely to recall memories and emotions in which that posture had been operational. Thus, gestures, facial expressions, and posture are not only reflections of emotion but actively participate in the subjective experience of emotion and in our interpretation of our experiences. A slumped posture may tell us that our self-esteem is low or that we are depressed, whereas an erect, upright posture may inform us that we are feeling good; a mouth turned up in a smile both contributes to and reflects feelings of happiness, contrary to a mouth turned down in a frown.

Action may even precede the emotion, especially when we are threatened: “We react automatically, and only later (even if it is only a split second later) do we realize there is danger and feel afraid” (Hobson, 1994, p. 139). Actions are immediately followed by the brain’s appraisal to determine the meaning of the sensation, action, and situation, and only then are the sensations interpreted as a sense of peril (Siegel, 1999). Thus, like posture and action, interoception informs us about, and is the result of, emotion. The sensation of tension in the jaw, shoulders, or arms not only conveys to us that we are angry but also serves to sustain the anger; a tingling sensation may be the result of a frightening experience and also tells us that we are afraid; the jittery sensation of butterflies in the stomach both results from and is causative of feelings of nervousness or excitement. These internal sensations equally reflect and stimulate the postures, gestures, and facial expressions that are the outward signs of emotional states.

Nina Bull’s (1945) extremely relevant theory that “motor attitude” precipitates emotion, which only then leads to behavior, highlights the impact of the way we hold our bodies on how we feel. She defines motor attitude as “the preliminary motor set, or posture of the body” that precedes and paves the way for particular emotions, which, in turn, motivate the physical action. Bull posits that “we feel angry as a result of readiness to strike, and feel afraid as a result of readiness to run away, and not because of actually hitting out or running” [p. 211, emphasis added]. Bull goes on to say that even preceding the motor attitude is a “predisposition,” the latent neural organization—a procedurally learned tendency—to execute particular motor attitudes, emotions, and overt actions.

Bull’s theory encompasses one very important difference from the idea that emotion is the result of and follows action (e.g., “I am afraid because I run”), a theory that Bull (1945, p. 210) believes “failed to differentiate between attitude and action, the…idea that feeling comes before behavior could find no place in [this] scheme.” Damasio (1999) recognized this point in his description of awareness of emotion being only part of what is meant by emotions: The bodily sensations and physiological changes may reflect “dispositional tendencies” that appear similar to Bull’s “motor attitude.” Porges (Chapter 2, this volume) writes that neurophysiology determines the coming together of emotional expression and visceral states, because changes in the nervous system contribute to muscle activity, including facial expression and movements of the legs, arms, and trunk. Hurley (1999) takes this one step further by describing the continual feedback loops of emotion, perception, cognition, and behaviors, asserting that none precedes the others. The above concepts correlate well with Lane and Schwartz’s (1987) structural developmental model that categorizes the capacity to be aware of and describe emotions in the self, as well as in the other, in terms of five stages: physical sensations, physical action tendencies, single emotions, blends of emotions, and blends of blends of emotions.

This section would not be complete without reference to “emotional operating systems” (Panksepp, 1998a) or “action systems” (Ogden et al., 2006; van der Hart et al., 2006). These evolutionarily prepared psychobiological systems, each with its characteristic emotional valence, stimulate us to form close attachment relationships (motivated by love, longing, distress upon separation, and, when threatened, fear); explore (characterized by interest and curiosity); play (characterized by joy and laughter); participate in social relationships (motivated by feelings such as affection and conviviality); regulate energy (through eating, sleeping, etc.); reproduce (governed by lust and sexual drive); and care for others (motivated by emotions such as tenderness and compassion) (Bowlby, 1969/1982; Cassidy & Shaver, 1999; Fanselow & Lester, 1988; Lichtenberg, 1990; Lichtenberg & Kindler, 1994; Marvin & Britner, 1999; Panksepp, 1998a; van der Hart et al., 2006).

Action systems most likely form an evolutionary basis for procedural tendencies. As a particular action system is aroused, particular physical tendencies are stimulated that correspond with the emotions characteristic of that system. For example, the curiosity of the exploration system manifests in seeking and orienting movements that enable the investigation of novelty. The play system, characterized by laughter, involves a variety of movement patterns: tilting of the head; relaxed, open posture; nonstereotyped movements that change quickly (Beckoff & Byers, 1998; Beckoff & Allen, 1998; Brown, 1995; Caldwell, 2003; Donaldson, 1993). The caregiving system manifests in “subtle, warm, and soft” (Panksepp, 1998a, p. 247) behavior as the caregiver attunes voice, behavior, and touch to the needs of the person for whom he or she is caring. A wide variety of social behaviors accompany social communication, including gestures, facial and bodily expressions, and vocalizations. The reproduction system incorporates particular movement sequences characteristic not only of sexual behavior but also of courtship and flirting: eye contact, smiling, vocalizations that are both of a higher pitch and augmented volume, and exaggerated gestures (Cassidy & Shaver, 1999). As these actions, designed to fulfill the purpose of their related action system, are repeatedly executed, procedural tendencies related to the arousal of that system are formed.

Trauma-Related Emotional Tendencies

To reiterate, animal defensive strategies and their corresponding emotions stimulated by threat are adaptive in the moment of immediate peril, but both tend to become inflexible tendencies in people with posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and other trauma-related disorders. Once danger is assessed, emotional arousal, now commonly interpreted as terror or anger, serves to support instinctually driven animal defensive strategies (Frijda, 1986; Hobson, 1994; Rivers, 1920). These dysregulated emotions tend to persist for traumatized individuals, who are characterized as suffering not only from “feeling too much” but also from “feeling too little” (van der Kolk, 1994). Sympathetically mediated mobilizing defenses entail an amplification of subjective emotional states—feeling too much—which is very different from the dampening and deadening of subjective emotional states—feeling too little—that typically accompany the immobilizing hypoarousal defense (Ogden et al., 2006; van der Hart et al., 2006). Fear and terror corresponding with flight responses may become chronic, repeatedly triggered by conditioned stimuli. Those with a dysregulated “fight” defense may be emotionally reactive, angry, or violent, at the mercy of bouts of rage with minimal provocation. Patients who favor a freeze response report helplessness and panic associated with feeling paralyzed, whereas “feigned death” and submissive responses, accompanied by increased dorsal vagal tone, herald a subjective detachment from, or absence, of the emotions, as indicated by patients who report, “I just wasn’t there; I didn’t feel anything.” Chronic immobilizing responses provoke feelings of helplessness, loss of internal locus of control, lessening of self-worth, and an inability to be effectively assertive (Krystal, 1988). Blaming themselves, patients then succumb to shame and further feelings of inadequacy and despair, particularly if they fail to understand that a lack of assertion is often the result of a tendency to depend upon immobilizing defenses for safety and not merely a psychological shortcoming.

The dissociative tendencies of traumatized individuals may also engender distinct emotional states corresponding with different internal dissociative parts of the self. As van der Hart et al. (2006, pp. 98–99) note: “Discrete alternations of affect (as well as accompanying thoughts, sensations, and behavior) may accompany switches among various dissociative parts of the personality because they may each encompass different affects and impulses.” Patients with dissociative disorders may experience further affect dysregulation as a result of conflicting emotions among various parts of the personality: One may be aggressive, another fearful, while yet another desperately seeks proximity and attachment (van der Hart et al., 2006). It is also important here to note that parts interact with each other internally: As one part engages in an attachment cry, a fight part may be stimulated, which in turn evokes flight or freeze among other parts, etc. These various parts of the personality, with their accompanying emotions and physical action tendencies, may routinely intrude unbidden upon the daily functioning of survivors, adding profoundly to their distress and dysregulation.

Failing to adequately integrate emotion arousal and adaptive action over time, patients may experience emotions as urgent calls to explosive, dysregulated action or complain of depression lack of action and motivation, or alternate between bouts of impulsive action and stagnation. Trauma-related emotions tend to remain constant over time and are exacerbated by current internal and external triggers, causing survivors to endlessly relive the emotional tenor of previous traumatic experiences.

Attachment-Related Emotional Tendencies

Trauma-related emotions, described above, interface with equally powerful attachment-related emotions that are the result of “both the relational processing in intense affective experiences and the long-term consequences of internalizing the dyadic handling of such experiences” (Fosha, 2000, p. 42). Particular emotional tendencies are found with each attachment category; these tendencies interface with, but are distinguished from, the powerful emotions that correspond with trauma-related animal defenses.

Those with insecure patterns develop habitual emotions and expressions that are defenses that minimize or block frightening or aversive affects (Fosha, 2000; Frijda, 1986). These relational defensive emotions and their functions are to be distinguished from those corresponding with animal defenses activated under perceived conditions physical danger and life threat. The relational defenses are most likely built on animal defenses, but they are much more sophisticated psychologically, being the result of a “higher-order consciousness” that includes the concept of a sense of self and a conceptual grasp of past, present, and future (Edelman, 1999). The affects associated with relational defenses limit the negative impact of painful emotions that evoked inadequate or inappropriate regulation and empathy from caregivers. In adult patients, these patterned emotions may be experienced as familiar and habitual, circular, endless and without resolution, and they go hand in hand with physical tendencies related to attachment (described above).

Individuals with insecure–avoidant attachment histories typically dismiss signals of internal distress and minimize emotional needs. Having lost hope that communicating negative emotions would elicit caregiving to regulate them, such individuals may fail not only to communicate emotions but to even experience them. Dependent on autoregulation and parasympathetic (dorsal vagal) dominance (Cozolino, 2002; Schore, 2003a) to self-regulate, emotional experience is thus curtailed (Cassidy & Shaver, 1999). This “overregulation” indicates a reduced capacity to experience both positive and negative emotions (Schore, 2003). Having lost access to strong emotions, as well as to a broad range of affect array, such patients typically present with a flat affect. Affective experience has been forfeited in favor of functioning, leading to “isolation, alienation, emotional impoverishment, and at best, a brittle consolidation of self” (Fosha, 2000, p. 43).

In contrast, the emotionality of patients with insecure-ambivalent attachment histories stems from the childhood experience of an undependable caregiver whose attention could be obtained only intermittently by clingy, needy behavior and increased emotionality. The amplified signaling for attention leads to escalating distress (Allen, 2001), which results in increased emotional reactivity in adulthood, an inability to modulate distress, and a vulnerability to underregulatory disturbances (Schore, 2003a). Preoccupied with internal emotional states, such patients are prone to dysregulated affect blended with high anxiety (Fosha, 2000). Relating a problem in her marriage to her therapist, Carmen tearfully leaned forward, gestured dramatically, her face exceedingly expressive and insistent on eye contact, wrapped up in her own distress and expression rather than in genuine contact, and unaware of her intrusion upon the physical “boundary” of her therapist or her therapist’s discomfort with Carmen’s “too close” proximity. Instead of enhancing interpersonal connection, the emotionality of this pattern sabotaged authentic contact.

The individual with a disorganized/disoriented attachment history grew up with attachment figures that provoked extremes of low (as in neglect) and high (as in abuse) affects that tend to endure over time (Schore & Schore, 2008). Experiencing high sympathetic tone—intense alarm, higher cortisol levels, and elevated heart rate—vacillating with increased dorsal vagal tone—slowed heart rate and shut down (Schore, 2001)—these infants, and later adults, are left with an inability to effectively auto-or interactively regulate. They suffer from rapid, dramatic, exhausting, and confusing shifts of intense emotional states, from dysregulated fear, anger, or even elation, to despair, helplessness, shame, or flat affect. These commonly become enduring patterns of various dissociative parts, some of which avoid interactive regulation, and some of which avoid autoregulation, and most of which are good at neither.

In contrast to those with insecure attachment histories, individuals with a history of secure attachment typically demonstrate a degree of “affective competence” that includes “being able to feel and process emotions for optimal functioning while maintaining the integrity of self and the safety-providing relationship” (Fosha, 2000, p. 42). However, although the attachment figures of the securely attached child provide adequate regulation and repair, nevertheless particular emotional responses are commonly favored over others even in the best of families. The habitual interpretation of emotional arousal in predictable ways leads to biases toward certain emotions. For example, Jim, securely/autonomously attached and successful and content in his marriage and his job, habitually interpreted sensations of emotional arousal as frustration and anger, having grown up in a family that minimized vulnerable emotions of sadness, hurt, and disappointment. He had narrowed his affect array in order to “fit into” his family, and the emotions of sadness and grief remained unacknowledged and unresolved. In contrast, Leslie demonstrated an affinity for sadness, avoiding feelings of anger or outrage—a tendency developed in a family that favored the more vulnerable feelings over more aggressive and assertive ones. To maximize the availability of her caregivers, Leslie suppressed feelings of anger. These emotional tendencies are also accompanied and sustained by somatic tendencies that limit the individual’s range of affect, but which do not necessarily indicate insecure histories.

Patients with both secure and insecure attachment histories exhibit patterns of decreased affect array related to innate action systems as a result of responses of early attachment figures to the arousal of these systems. Some patients with excessively serious parents have trouble playing; others who grew up in overly protective environments are uncomfortable with the curiosity of exploration; some are awkward and self-conscious in groups; still others seem unable to experience adequate empathy to motivate effective caregiving behavior; and some whose attachment figures frowned on flirtations behavior remain stilted and awkward during courtship. Important components of therapy include noting physical and emotional tendencies related to the arousal of various actions systems, helping patients work through the emotional pain when the arousal of particular systems has evoked disapproval or danger, and then cultivating the suppressed emotions and actions related to each system.

A Note on Play and Positive Affect

The capacity for play and positive affect is typically diminished or absent in patients who have come to associate positive affect with vulnerability to ridicule, disapproval, disdain, or even danger. A broad variety of positive affect states depend upon the ability to regulate a wide range of arousal, which, in childhood, is facilitated by the caregiver’s sensitive, attuned responses to both positive and negative affect. The “good enough mother” (Winnicott, 1945) actively engages with her infant, repeatedly pairing high arousal states with interpersonal relatedness, play, and pleasure, while also helping the child to recover from negative states of distress, fatigue, and discomfort. Thus, “Affect regulation is not just the reduction of affective intensity, the dampening of negative emotion. It also involves an amplification, an intensification of positive emotion, a condition necessary for more complex self-organization” (Schore, 2003a, p. 78).

Play and other positive affective states cannot develop in the shadow of threat and danger, or under the scrutiny of a strict, disapproving, or overly serious attachment figure. They depend upon the subjective experience of safety and comfort, but for many patients, competing states of uneasiness or fear impede these states. Qualities of spontaneity, vitality, pleasure, and flexibility, as well as the trust and resonance required to engage in a deeply satisfying intimate relationship, are precisely the traits that are incompatible with trauma-related procedural learning. Many attachment-related tendencies formed when caregivers were not playful themselves, were overly critical of normal childhood foibles and ebullience, or unduly emphasized achievement, order, and etiquette rather than spontaneity and fun, interfere with positive affect and playfulness.

Many patients have become more accustomed to actions and goals that have to do with avoiding pain and fear than with seeking out positive affect. Preoccupied with the possibility of danger, criticism, or rejection, they have not learned to attend to things, people, or activities that might bring them pleasure. Such clients report that they do not know their own preferences—what activities would bring them pleasure, satisfaction, joy, or other feelings of well-being, what they are curious about or interested in, or what sensory stimuli feel good or meaningful to them (Migdow, 2003; Resnick, 1997).

Trauma-and attachment-related physical tendencies are typically inflexible and lack spontaneity. Movements characteristic of nonplayful or overly serious interactions tend to be constrained, stereotyped, rigid, agitated, or nervous (Beckoff & Byers, 1998; Brown, 1995). In some cases, such as that of the patient who complained of being scattered, impulsive and incapable of commitment, uncontained and impetuous, flitting movements reflected procedural tendencies. In treatment, explorations that increase the patient’s ability for play and positive affect can mitigate maladaptive procedural tendencies. The therapist tracks the bodily responses evoked by the patient’s narrative, alert not only to indications of trauma-and attachment-related procedural tendencies, but also to expressions characteristic of social engagement, positive affect, and play. These may be observed in a relaxed, open body posture, a tilting of the head (Beckoff & Allen, 1998; Caldwell, 2003; Donaldson, 1993), expressive gestures, or movements that shift quickly and are nonstereotyped (Goodall, 1995). Even early on in therapy, patients may experience short-lived moments of pleasure, playfulness, and resonant connection with the therapist that include particular nonverbal gestures, postures, and movements, such as a spontaneous increase in proximity and gesture, enhanced social engagement, eye contact, and relaxed, mobile facial expressions (Beckoff & Allen, 1998). The therapist meticulously watches for incipient spontaneous actions and affects—the beginning of a smile, meaningful eye contact, a more expansive or playful movement—that indicate positive affect, and capitalizes on those moments by participating in kind and/or calling attention to them and expressing curiosity, enabling the moment to linger. Encouraging simple joy, humor, and lightheartedness that accompany play behavior and the feelings of competence, joy, peace, love, and the authentic expression of other positive affects can counter the often arduous work of therapy and help patients expand their regulatory boundaries to include intense positive emotions as well as negative ones.

Directed Mindfulness and Treatment

To discover and change procedural tendencies, the therapist is interested not only in the narrative or “story,” but in observing the emergence of procedural tendencies in the here and now of the therapy hour. Through the practice of mindfulness, patients learn to notice rather than enact or “talk about” these tendencies. Therapist and patient together “study what is going on, not as disease or something to be rid of, but in an effort to help the client become conscious of how experience is managed and how the capacity for experience can be expanded” (Kurtz, 1990, p. 111). Because mindfulness is “motivated by curiosity” (Kurtz, 1990, p. 111), it “allow[s] difficult thoughts and feelings [and body sensations and movements] simply to be there, to bring to them a kindly awareness, to adopt toward them a more ‘welcome’ than a ‘need to solve’ stance” (Segal et al., 2002, p. 55). Mindfulness also includes labeling and describing experience using language (Kurtz, 1990; Ogden et al., 2006; Siegel, 2007). Such nonjudgmental observation and description of internal experience engages the prefrontal cortex in learning about procedural tendencies rather than enacting them (Davidson et al., 2003). Since emotions and procedural tendencies are the purview of the right hemisphere (Schore, 2003a), whereas language is the purview of the left hemisphere, mindfulness may serve to promote communication between the two hemispheres (Neborsky, 2006; Siegel, 2007).

Mindfulness is an activity that is similar to, but different from, the concept of “mentalizing”—the process by which we make sense of the contents of our own minds and the minds of others (Allan, 2008; Fonagy et al., 2002). Although the process of mentalizing can be conscious, involving explicit reflective functioning, it often occurs automatically, without thought or deliberation. Such “implicit” mentalizing is influenced by many factors, including the posture, sensation, and movement of the body as well as chronic and acute emotional states. For example, the mentalizing of an individual whose body is constricted and tense is different from that of an individual whose body is tension free; the mentalizing of one whose spine is slumped and shoulders rounded forward is different from that of another whose spine is erect and shoulders square. Through mindfulness, we become aware of such procedural tendencies as contributing to implicit mentalizing. Then mentalizing can become more explicit as these implicit phenomena are brought into consciousness and reflected upon. Mindful is also useful in changing procedural tendencies so that implicit mentalizing becomes more adaptive and responsive to current life situations instead of the past.

Definitions of mindfulness usually describe being open and receptive to “whatever arises within the mind’s eye” (Siegel, 2006) without preference. “Directed mindfulness” (Ogden, 2007) is an application of mindfulness that directs the patient’s awareness toward particular elements of present-moment experience considered important to therapeutic goals. When patients’ mindfulness is not directed, they often find themselves at the mercy of the elements of internal experience that appear most vividly in the forefront of consciousness—typically, the dysregulated aspects, such as panic or intrusive images, which cause further dysregulation, or their familiar attachment-related patterns. An example of nondirected mindfulness would be a general question to a dysregulated patient such as, “What is your experience right now?” An example of directed mindfulness that guides a patient’s attention toward meeting the goal of becoming more grounded would be, “What do you notice in your body right now, particularly in your legs?” The patient likely will report that she cannot feel her legs, which paves the way for generating sensation and movement in her legs by bringing her attention to them, thus promoting the therapeutic goal of groundedness. Directing mindfulness toward emotions or the body makes it possibly to utilize precise interventions targeted at emotional processing—the experience, articulation, expression, and integration of emotions—as well as sensorimotor processing—the experience, articulation, expression, and integration of sensations and physical actions.

Expanding the Regulatory Boundaries of the Window of Affect Tolerance

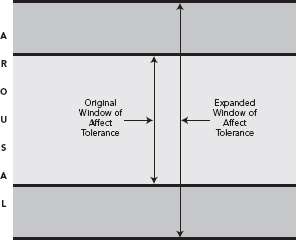

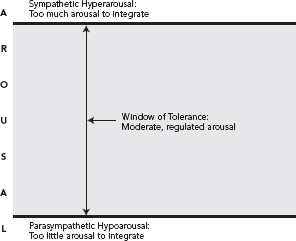

The “window of affect tolerance” refers to an optimal arousal zone within which emotions can be experienced and processed effectively. Hyper-or hypoaroused states exceed the window of affect tolerance and are not conducive to the efficacious processing and resolution of emotional states. Trauma and maladaptive attachment tendencies will narrow the window of tolerance, and it is essential to expand these boundaries (see Figure 8.1).

FIGURE 8.1

The window of affect tolerance.

Expanding the patient’s regulatory boundaries involves experiencing and expressing core emotions, integrating dissociated or masked emotions, increasing the capacity for positive affect, and challenging physical procedural tendencies with new actions. Although these emotions and new actions are sometimes intense and painful, they also have a sense of aliveness, novelty, and richness and serve to connect patients with deeper layers of their emotional array. The activation and processing of these emotions leads to new resources, energy, and meaning (see also Fosha, Chapter 7, this volume; Trevarthen, Chapter 3, this volume).

The regulatory boundaries of the window of affect tolerance are challenged and expanded in psychotherapy as patients execute new, empowering physical actions, impossible during an actual traumatic event, or perform previously ineffective relational actions that foster attachment, connection, and interpersonal resonance, or engage the variety of actions that encourage and reflect positive affect (see Figure 8.2). Core affects are supported by the elaboration of corresponding physical actions: Adaptive anger is supported by increased alignment of the spine, a degree of physical tension, and the capacity to push away or strike out; joy, by an uplifting of the spine and expansive movement; empathy, by a softening of the face and chest, and perhaps a gentle reaching out; play, by a tilt of the head, and spontaneous, rapid changes in movement.

FIGURE 8.2

Expanding the regulatory boundaries of the window of affect tolerance.

However, venting the associated patterned emotions often exacerbates procedural tendencies, repeats the past, and thus fails to expand the regulatory boundaries. Thus, it is important that therapists assess the nature or source of a patient’s emotional arousal: patterned, procedural tendencies that include dysregulated animal defensive responses, trauma-related hyperarousal or emotional tendencies; habitual emotions stemming from attachment history; or an authentic emotional response that expands the affect array, finishes unfinished business, reclaims emotions that have been dissociated, devalued, or suppressed, or increases positive affect tolerance.

Bromberg (2006) states that “retelling is reliving” and that while therapists must “try not to go beyond the patient’s capacity to feel safe in the room, it is inevitably impossible for him to succeed, and it is because of this impossibility that therapeutic change can take place” (p. 24). Work with strong, authentic core emotions and new physical actions can precipitate excessive arousal that surpasses the patient’s integrative capacity. These new emotions and actions typically cause arousal to escalate to the borders of dysregulation and require attentive and sensitive regulation by the therapist, who assures that arousal is high enough to expand the window, but not so high as to sacrifice integration. On the other hand, if patients’ emotional and physiological arousal consistently remains in the middle of the window of tolerance (e.g., at levels typical of low fear and anxiety states), they will not be able to process past experience or expand their physical and emotional capacities because they are not in contact with traumatic or affect-laden attachment tendencies in the here and now of the therapy hour. Thus, as Bromberg states, therapy must be “safe but not too safe” in order to expand the window of affect tolerance.

Therapist and patient must continuously evaluate the level of arousal and the patient’s capacity to process at the regulatory boundaries of the window of tolerance. Once arousal is at the regulatory boundaries, it is imperative to avoid stimulating additional emotional or physiological arousal and to avoid continuing with physical actions that cause further dysregulation at the expense of integration, working instead at the boundary with intention toward integration.

Working with Trauma-Related Tendencies

The overarching aim of trauma therapy is integration. At the beginning of therapeutic work with traumatized individuals, arousal typically becomes dysregulated (i.e., exceeds the patient’s window of tolerance) both by the relationship and by articulation of the traumatic events. Abreaction and expression of trauma-related emotion that takes place far beyond the regulatory boundaries of the patient’s window of affective tolerance is not encouraged because it does not promote integration (van der Hart & Brown, 1992). But through attending preferentially and exclusively to sensorimotor processing when arousal is at the edge of the window of tolerance, patients learn that the overwhelming arousal can be brought back to the window. This can be done independent of any particular emotional or cognitive content. Noticing and changing somatic tendencies in the present to the exclusion of emotions and content limit the information to be addressed to a tolerable amount and intensity that can be integrated, facilitates affect regulation, and paves the way for future work with strong emotions without causing excessive dysreglation.

The first task of therapy is to teach patients particular skills that serve to return their arousal to within the window of tolerance. After years of celibacy, Marcia, a sexual abuse survivor, began to explore sexual intimacy with her boyfriend, which in turn triggered bottom-up dysregulation. She reported in therapy, “My body’s gone amuck! I can’t sleep, I can’t eat!” Asked by her therapist to “notice what happens inside” (an open-ended, general mindfulness directive), Marcia reported panic and trembling, an awareness that exacerbated her dysregulation. Marcia’s therapist then used directed mindfulness by asking Marcia to pay attention only to her body sensation, thus excluding descriptions of emotions and content: “Let’s just focus on your body: Feel the panic as body sensation—what does it feel like in your body?” Marcia directed all her attention to the sensation of trembling, using sensation vocabulary (e.g., tingling, traveling, shaking, calming down) rather than emotion vocabulary (e.g., scared, ashamed, panicked, anxious) to describe her somatic experience to her therapist. To encourage Marcia to describe the progression of these sensations until the sensations themselves subsided, her therapist continued to use directed mindfulness: for example, “Stay with that sensation of trembling—what happens next in your body? How does the sensation change?” Gradually, the sensations settled, the trembling abated, and Marcia’s arousal returned to her window of tolerance.

Directed mindfulness can also help patients discover empowering, mobilizing defenses. In 1925 Janet wrote about his observation that traumatized patients are unable to execute empowering actions, or “acts of triumph” (p. 669). When patients first turn their attention to the body, they typically become aware of disempowering, immobilizing defenses rather than triumphant actions. But as they learn to extend and refine their mindfulness of the body, they nearly always discover the impulses to fight or flee that were inhibited, for the sake of survival, during the original traumatic events but remain concealed within the body. These empowering actions often first reveal themselves in preparatory movements—the barely perceptible physical actions that occur prior to the full execution of a larger movement.

For example, as Marcia first talked about the abuse she had suffered as a child, she was aware only of the collapsed feeling in her body and a tendency toward hypoaroused responses: spacing out, feeling “nothing.” However, as she continued to explore body sensations, she noticed a slight tightening in her jaw, tension that seemed to travel down her neck into her arms. Eventually, Marcia reported a small movement in her fists, a curling that seemed indicative of a larger aggressive movement. As she was directed by her therapist to feel the tension and to see what her body “wanted to do,” Marcia became aware of impulses to strike out, and she slowly executed this motion against a pillow held by her therapist. Upon the completion of that movement, Marcia also reported the impulse to escape, experienced as a tightening of the muscles of her legs, which was executed through standing and experiencing her ability to walk away from unwanted stimuli.

Working with such physical acts of triumph is interwoven with working with patterned emotions and eventually with adaptive new emotional responses. At one point, as Marcia remembered her father coming into her bedroom when she was a child, her hands came up in a protective gesture, but then her hands suddenly drew in toward her body. Asked to notice this movement, Marcia expressed being ashamed, an aversive emotion that corresponded with impulses to curl up instead of protecting herself through pushing motions. As Marcia followed the impulse to curl up, she was able to experience her feelings of shame with her empathically regulating therapist, who not only facilitated Marcia’s emotional expression but also the realization that the abuse was not her fault. However, this was only a step in Marcia’s process, for the empowering “act of triumph” of pushing away remained incomplete and unexecuted. Thus, upon the settling of her emotional arousal, the therapist asked her to return to recalling the moment when her father came into her bedroom when she was a child and discover what her body “wanted to do,” again facilitating not only somatic awareness but somatic processing. This time, Marcia reported a feeling of anger—contrary to her usual pattern of helplessness, shame, and fear—accompanied by tension in her arms, which proved to be the nascent mobilizing defense that she had, wisely, abandoned during the abuse. This time, Marcia was able to sustain directed mindfulness toward the anger and her somatic experience, both of which supported the execution of a new action as opposed to the repetition of submission and shame.

In previous therapy, Marcia had repeatedly expressed tendencies of shame and helplessness, but her propensity to dissolve into tears interfered with more adaptive emotional and physical responses such as anger and assertive action. Once she discovered her anger at what had happened and was able to execute her acts of triumph, she reported a core feeling of “being safe in my skin” and “more like myself than I’ve ever experienced.” As she and her therapist shared their deep appreciation for these gains, Marcia began to cry softly. She expressed deep grief at the loss of the innocent trust in her father that she had treasured as a young girl. These very powerful emotions were accompanied by another surge of arousal, challenging the regulatory boundaries of her window of tolerance, but, as she sobbed, her therapist’s empathic voice and interactive regulation kept Marcia from further escalation, resulting in an expansion of her window of affect tolerance and sense of competency. Afterward, Marcia reported that that she felt a new sense of fluid movement and an overall softening and receptivity in her body.

Treatment of Attachment-Related Tendencies

Aversive attachment-related affects, such as shame or defenses that mask or suppress a deeper emotion, recapitulate early affect-laden interactions with caregivers and limit affective experience, array, and expression. These emotions typically formed as successful strategies for meeting needs where direct authentic emotional communications proved unsuccessful, have a repetitive quality, and often disguise and defend against a deeper level of feeling. Geared to these needs, patterned emotions are used manipulatively (unconsciously, not maliciously) to influence the actions of others by stimulating guilt or sympathy or eliciting attention, help, empathy, freedom from pressure, privacy, or connection. Instead of venting these patterned emotions unawares, it is important to help patients both discover their function and experience the underlying or authentic or “core” affects (Fosha, 2000). Core affects provide a sense of deep contact and comfort with the self and the self in relationship: the experience and expression of the emotional pain unmasked of the defensive emotion, and the joy, pride, love, and deep resonance in the dyadic context.

Jim was quick to anger, expressing frustration and irritation at the slightest provocation. When this patterned response emerged as he was talking about his wife’s criticism of him, his therapist asked him to focus on the somatic tendencies that correlated with the emotion. He first reported tension in his jaw, arms, and shoulders and expressed additional feelings of anger. The therapist empathically reflected his affect but also directed continued mindfulness toward his body rather than his emotions. As Jim refrained from expressing the anger and stayed aware of his body, he noticed tension in his chest. Recognizing this sensation as different from the physical tendency accompanying his characteristic anger, the therapist directed Jim to focus on that tension, notice its parameters, and to exaggerate it slightly (intending to raise the signal of a more core emotion). Jim reported that his heart hurt, and he spontaneously recalled a memory of his parents strongly ridiculing him for failing to successfully help his younger sister with her homework. The tension around his heart increased, and the therapist again asked him to stay aware of his body and to find the words that seemed to accompany the tension. Jim said softly, “I can’t show my hurt—I have to be tough,” and with those words, the underlying emotion of hurt and disappointment masked by the pattern of irritation and anger, emerged and deepened. The therapist’s empathic resonance provided the opportunity for complete expression of this underlying, defended core affect and allowed Jim to cultivate new, more adaptive emotional responses. Over time, Jim was able to express a variety of core emotions and also learned to engage in new, more adaptive physical actions. He practiced softening the area around his heart to enable connection with more vulnerable emotions: He placed his hands gently over his heart, consciously relaxed his chest, and used his breath to soften his chest. He learned to become mindful of physical actions indicative of anger and frustration, such as tension in his jaw, arms, and shoulders, and to discern if these represented fixed reaction patterns or adaptive responses to the present moment.

Awakening and Regulating Play and Positive Affect

The therapist’s encouragement of a wide variety of positive affects and their physical actions expands the boundaries of the window of tolerance and offers the potential for increasing the capacity for social engagement and trust in relationship. In the context of sensitive attunement and collaboration, the patient can learn to become more curious and mindful of internal experience in response to the thought, remembrance, or engagement of play and positive affect, to the movements that express them, or to spontaneous moments of playful interaction and positive affect with the therapist.

Joan reported to her therapist that she is often told she is “too serious” and that her husband complains of her inability to enjoy herself. These observations were corroborated by her bodily communications: Joan’s body was stiff, pulled in, awkward in its rigidity, telegraphing a nonverbal message to “keep away” emotionally and physically. The tension across her hunched shoulders, a lack of movement and freedom in her upper body, and a plodding quality to her gait echoed Joan’s feeling that she was accustomed to great hardships. Though Joan wistfully spoke of wishing that she could experience greater enjoyment in life, she also reported a sense of discomfort and even alarm when she attempted to be less serious or more playful. Having grown up with a maternal caregiver who was strict, somber, anxious, and depressed and who provided little protection from the frightening behavior of an alcoholic father, we can infer that, as an infant and child, Joan experienced inadequate soothing of her states of distress and a loss of playful, positively toned mother–child interactions.

Initially, the therapist’s attempts to help Joan embody the flexible, unstereotyped movements characteristic of positive affect ignited procedurally learned animal and attachment defensive tendencies. As Joan began to explore expressive, playful movements, she reported tension and constriction in her body that told her to expect ridicule or even danger. Her therapist taught her how to practice a mobilizing defensive response of pushing away, utilizing the tension in a gesture of boundary setting and protection. This movement was practiced again and again, gradually fostering a sense of safety and mastery that alleviated her fear and frozen immobilization.

Eventually, Joan’s therapist asked her what kind of posture and movements her body would want to make in a context of enjoyment, fun, and safety, and Joan reflected that those actions would be free, spontaneous, and expressive—qualities that challenged her usual restrained, stiff demeanor. In a carefree, playful manner, the therapist executed such movements (tilting of the head, dancing motions with legs and arms) at Joan’s instruction, first modeling them for her and then asking her to explore mirroring these movements. Initially, Joan giggled, but then again reported that these playful actions felt frightening, and she felt the impulse to curtail the movements and return to her habitual tension. But since much work had already been done with regard to her fear and the corresponding physical tendencies, her therapist remained empathically playful, helped her sense the safety of the here and now, encouraged her to maintain eye contact, and also reminded her of her newly learned ability to set boundaries and say “no.” With this support, Joan was able to explore spontaneous, relaxed, expressive movements characteristic of positive affect.

Over the course of therapy, Joan and her therapist practiced a variety of movements that facilitated positive affect, such as comparing Joan’s plodding gait with a bouncy, “head up” walk, exchanging her hunched shoulders and rounded spine for an upright, shoulders-down posture that encouraged eye contact and engagement with others. With continued practice, Joan’s more integrated posture and expressive actions as well as positive affects became more natural and accessible, and her movements became increasingly unpredictable, unforced and complex, occurring without prompting from her therapist. While her emotional arousal increased during many moments of experiencing a variety of positive affects (playfulness, joy, elation, mastery, pride, reception of the therapist’s positive regard, deep resonance and even love between therapist and patient), high arousal was paired with positive affect, in marked contrast to her usual coupling of high arousal with negative affect, danger and hypervigilence. Over time, experiencing and enhancing positive affects and amplifying their accompanying movements challenged Joan’s procedural tendencies, fostered resilience and buoyancy, stimulated social engagement, and expanded her window of tolerance.

Conclusion

Underscoring the relationship between affect, the body, and the brain, Ratey (2002) writes: “When we smile we feel happier and when we feel happier we smile…. The feedback between layers or levels of the brain is bidirectional; if you activate a lower level, you will be priming an upper level, and if you activate a higher level, you will be priming a lower level” (p. 164). Clinicians can utilize the feedback between emotions, sensation, and physical action to therapeutic advantage by integrating direct work with movement and body sensation into their skill base. Although addressing emotions (and cognitions) is essential in treatment, it is no substitute for the meticulous observation of procedurally learned physical tendencies or the thoughtful interruption of them that teaches patients to use their own movement, posture, and sensation to regulate arousal and expand their own affect-regulating capacity. The successful accomplishment of previously feared or unfamiliar actions in the context of an attuned social engagement with the therapist, along with appropriate processing of previously feared or unfamiliar core emotions, serve to develop more adaptive relational capacities, strengthen both interactive and autoregulatory abilities, and expand the regulatory boundaries of the window of tolerance. A comprehensive integration of work with emotion and elaboration of physical actions maximizes therapeutic possibility and, over time, inspires patients to engage a wider range of life-enriching behaviors and affects.