Agreements Among Vegan and Non-Vegan Food Firms

Throughout this study, the authors propose possible agreements among different food producers, in order to develop a new better conceived diet for the future generations, by using a coopetitive approach and game theory. Specifically, the authors shall consider food producers and sellers of vegan (respectively, vegetarian) and non-vegan (or non-vegetarian) food. The coopetitive approach used by the authors provides a mathematical game theory model, which could help producers of vegan food a simpler entry in the market and free significant publicity. Meanwhile, the model could allow producers of non-vegetarian food a smooth transaction to vegetarian and vegan production. In particular, authors propose an agreement setting among McDonald's and Muscle of Wheat, because they think that Muscle of Wheat cannot enter a global market without the help of a large food producer already in the market. The game theory model represents an asymmetric R&D alliance between McDonald's and Muscle of Wheat.

General Perspective and Objectives

In this chapter, the authors study a game theory model for the sustainability of food production. Specifically, we construct a coopetitive model suggesting general possible alliances among vegan and non-vegan food producers. It is now well known that the meat production has begun non-sustainable, from several points of view. Moreover, the meat consumption reveals linked with heart strokes, cancers, diabetes and several other diseases. Indeed, affluent citizens in middle-income and low-income countries are adopting similar high-meat diets and experiencing increased rates of those chronic diseases. The industrial agricultural system (nowadays, the predominant form of agriculture in the USA and increasingly world-wide) - required for the meat and dairy production - determines consequences for public health, owing to:

Moreover, in industrial animal production, we emphasize the strong public health concerns for feed formulations, including animal tissues, arsenic and antibiotics. We underline also the strong concerns for the induced laborer health risks - coming from such unsustainable work - and also for the consequent related health hazards regarding the communities living close to the meat production factories.

A Game Theory Approach

We shall consider possible agreements among different food producers, in order to develop a new better conceived diet for the future generations, by using a coopetitive approach and game theory. Our coopetitive approach provides a mathematical game theory model, which could help producers of vegan food a simpler entry in the market and free significant publicity. Meanwhile, our model could allow producers of non-vegetarian food a smooth transaction to vegetarian and vegan production.

Economic Perspective

Everywhere, during the last years, the industry is taking increasingly more note of the evident circumstance that vegetarians and vegans worlds represent a very attractive economic target. Nowadays, indeed, the major brands of the food industry are trying to create more space for themselves in a food market increasingly less niche and continuously widening.

Vegan Consumption in Europe

In Europe, the “average” consumer shows an increasing interest for alternative foods with respect to meat and dairy products: it is evident the gradual growth in sales of products based on soy, almonds, coconuts, legumes, seeds, beans and other noble vegetables - coming from, also, a thorough marketing campaign which in recent years has extolled the virtues of the legumes health benefits (see Seclì, 2007).

Literature Reviews on Food Production

In this section we present, by citing some relevant sentences, some of the literature we used for the construction of our ideas about the sustainability of food production.

Problems with Meat Production

In an article of 2005 written by Walker, Rhubart-Berg, McKenzie, Kelling, and Lawrence, we read: “We live in a world of contradictions, where one billion people are overweight or obese and another one billion lack adequate food resources, despite the fact that current world food production could feed the 6.3 billion people on Earth (now 7.5 billion people), if distributed equitably and based on a diet with only moderate amounts of animal products Animal products, however, are the primary source of saturated fat responsible for higher risk of cardiovascular disease, diabetes mellitus and some cancers. Meat itself is also associated with increased risk of some cancers. An important public health challenge is to provide adequate amounts of protein and essential nutrients without also causing over-consumption of saturated fat” (see Walker et al., 2005).

Costs of Non-Vegan Food Production

Consider the following data about the costs of meat production as reported by Fiala (2008): “Current production processes for meat products have been shown to have a significant impact on the environment, accounting for between 15% and 24% of current greenhouse gas emissions. Meat consumption has been increasing at a fantastic rate and is likely to continue to do so into the future” (see Fiala, 2008).

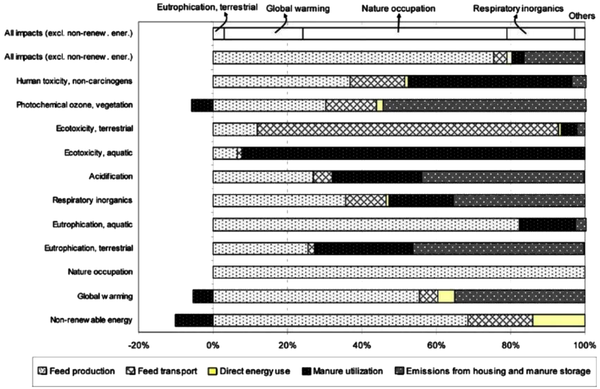

Moreover, in Nguyen, Hermansen, and Mogensen (n.d.), we read: “The environmental costs of meat are displayed as characterized results at different midpoint categories e.g. global warming, nature occupation, acidification, eutrophication, ecotoxicity, etc.

In decreasing order of importance, nature occupation has been found to be the main contributor to the costs (55%), followed by global warming (21%) and respiratory inorganics (18%).

A breakdown of the external costs into three damage categories shows that impacts on ecosystems obtain high importance with 80% contribution to the costs whereas impacts on human well-being and impacts on resource productivity carry relatively low importance with 15% and 5% contribution, respectively.

Approximately 75.4% of the environmental costs of pig meat production is related to feed production and the remaining is distributed among the other sub processes, “emissions from housing and manure storage”, “manure utilization for crop fertilization”, “feed transport and direct energy use” by 16.3%, 3.2%, 3.7% and 1.2% respectively.

As for the detailed information about on which part (or component) of the pig meat life cycle, the highest load of different environmental impacts occurs or the largest potential for improvements lies, Figure 1 summarizes the results of such analysis”.

For a deeper study you can read Nguyen et al. (n.d.).

| Figure 1. Breakdown of contributing sub-processes and contributing impact categories |

|---|

|

| Source: Nguyen et al., n.d. |

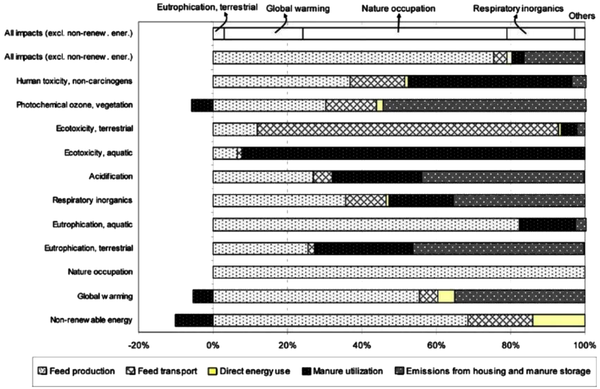

Meat and Sustainability: Data of the Consumption of Meat in the World

Recent data, however, show that in the US, with a population of 316 million in habitants, but also in other European countries, the consumption of animal products is decreasing: 6% between 2006 and 2010. Aided by the economic downturn, but even healthier lifestyles, responsible and sustainable - for example, is increasing in the number of vegetarians or vegans. Western countries are slightly changing their eating habits or keeping them less stable. Other countries see their meat consumption increase, i.e., very large and densely populated countries experiencing a period of strong economic growth. They are the BRICS countries (Brazil, Russia, India, China, South Africa) (see Figure 2).

| Figure 2. Estimated consumption of meat for person in kilograms in 2010-12, and forecast in 2022 |

|---|

|

| Source: Böll-Stiftung (2014, pp. 49) |

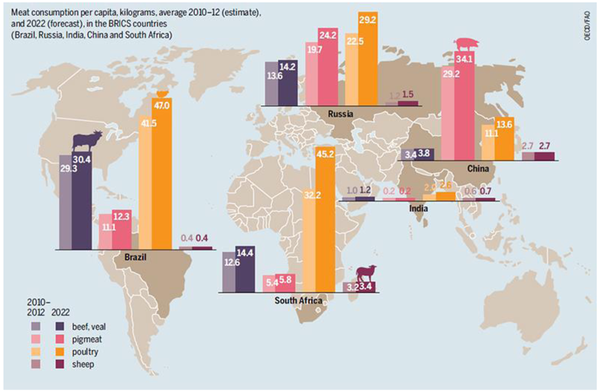

What the W.H.O. Said on Meat

Epidemiological studies suggest that increases in the risk of several cancers are associated with high consumption of red meat or processed meat. These risks are very important for public health because many people worldwide eat meat and meat consumption is increasing in low- and middle - income countries (See Figure 3).

| Figure 3. Worldwide Annual Meat Consumption per capita - Source: ChartsBin (2009) |

|---|

|

A group of 22 international experts, from 10 countries, examined more than 800 different studies on cancer in humans, and summarized the data in a document of IARC, the International Agency for Research on Cancer. Red meat was classified as “Group 2A - probably carcinogenic to humans”, and processed meat was classified as “Group 1 - carcinogenic to humans”. Processed meat has been classified in the same category as causes of cancer such as tobacco smoking and asbestos (IARC Group 1, carcinogenic to humans i.e. there is sufficient evidence of carcinogenicity in humans from epidemiological studies). The IARC classifications describe the strength of the scientific evidence about an agent being a cause of cancer, rather than assessing the level of risk. An analysis of data from 10 studies estimated that every 50 gram portion of processed meat and every 100 gram portion of red meat, eaten daily, increases the risk of colorectal cancer by about 18% and 17% respectively, if the association of red meat and colorectal cancer were proven to be causal (see WHO, 2015).

Why is Meat and Dairy So Bad for The Environment?

On The Vegan Society (n.d.) we read: “The production of meat and other animal products places a heavy burden on the environment - from crops and water required to feed the animals, to the transport and other processes involved from farm to fork. The vast amount of grain feed required for meat production is a significant contributor to deforestation, habitat loss and species extinction. In Brazil alone, the equivalent of 5.6 million acres of land is used to grow soya beans for animals in Europe. This land contributes to developing world malnutrition by driving impoverished populations to grow cash crops for animal feed, rather than food for themselves. On the other hand, considerably lower quantities of crops and water are required to sustain a vegan diet, making the switch to veganism one of the easiest, most enjoyable and most effective ways to reduce our impact on the environment” (see The Vegan Society, n.d.).

Leitzmann (2014) writes: “The future of vegetarian nutrition is promising because sustainable nutrition is crucial for the well-being of humankind. An increasing number of people do not want animals to suffer nor do they want climate change; they want to avoid preventable diseases and to secure a livable future for generations to come” (see Leitzmann, 2014).

Readings About Sustainability

In this chapter we used several additional by bibliography and sitography about sustainable food succeed: Gourmandelle (2015), Vegan Outreach (2014), MacMillan (n.d.), Universo Vegano (n.d.), Turnbull (2015), One Green Planet (n.d.), Knutson (n.d.), Gavin (2014), Vegan Starter Kit (n.d.), Messina (2010), Vegans of Color (2009), Staying Vegan (2010), Pimentel, D. and Pimentel, M. (2003), Wheeler (2015), Boston University (n.d.), Thomas (n.d.), Wick (2011), National Sustainable Sales (n.d.), AMP (n.d), Albanesi (2013), Lugano (2012), AdnKronos (2015), Oscar Green (2015), Veganblog (2015), Dutto (2015), Sclaunich (2015), Sacchi Hunter (n.d.), Etica Vegana (2016), Zanni (2013), Animalvibe (2015), Fiala (2008), Four Seasons Natura e Cultura (n.d.), Worldwatch Institute (2004), Whole Foods market (n.d.), Petroff (2015), Giambarrresi (2013), Leitzmann (2003), The Vegetarian Resource Group (n.d.), Shanker (2015), Mingolia (2015), Lusk and Bailey Norwood (2007), Mission 2015 (n.d.), Four Seasons Natura e Cultura (n.d.), Saint Louis (2015), Kjaernes, 2010.

Food Sustainability

Food sustainability implies several aspects, already considered widely in literature, for example (see Figure 4):

| Figure 4. Sustainable development - Source: Drolc (2013) |

|---|

|

Why Go Vegan?

In this section we shall consider some common motivations to go vegan.

(see The Vegan Society, n.d.).

Vegan Diet and Impact on the Territory

The vegan diet is clearly different than in vegetarian and omnivorous because it does not provide any form of intensive animal husbandry, truly responsible for the large consumption of resources caused by the major diets common in the West. Those practicing vegan chooses to minimize the burden on the company due to the chain of transformation of raw materials into food on our tables.

The calculation of the natural resource consumption for meat production is expressed taking into account the energy required for the collection of raw materials, the environmental costs of transportation of animals, the washing of animals, the animal feed and environmental costs also due to distribution. In assessing the impact of different diets on the environment, it does not come into play only quantitative assessments:

(see Non solo Vegan, 2014).

Case Study: The “Muscle of Wheat”

We will analyze the case of the “Muscle of wheat”, a food created by the Italian-Calabrese Enzo Marascio, from high quality agricultural product of his land.

It is a real evolution in the food industry, because it shows a nutrient value similar to that of meat, while it results totally vegetable. Wheat and pulses reveal the basic ingredients and make the muscle of wheat more complete than seitan, soy and tofu. It represents a good substitute for those who decide to limit or abolish the own consumption of meat and fish, by following a diet free of dangerous animal fat and cholesterol.

Thanks to a special processing and fermentation, a mixture of wheat flour and pulses it assumes a consistency surprisingly similar to that of meat. Marascio is able to reproduce, with this new raw material - from himself named “Muscle of wheat”, given his impressive consistency - many traditional plates of meat, such as dried beef, some salami, roast beef, etc (see Figure 5, Figure 6, Figure 7).

There seems to exist a big difference between the invention of Marascio and substitutes meat more known and consumed by vegans, like seitan, tempeh, soy steaks. While the latter are derived from a de-structuring of the raw material used, Muscle of wheat develops exclusively on the basis of a dough, without the intervention of artificial modifications of the basic molecules. Moreover, this new product gains a specificity from legumes and cereals put together, not from a major modification of a single raw material: for this reason, the nutrient profile of the muscle of wheat is better.

Muscle wheat has undergone numerous surveys: in particular, in 1992 was analyzed by Prof. Fernando Tateo of the University of Milan and, surprisingly, turned out to be a food very particular: it contains, in fact, 20 amino acids, including the essential 7 amino-acids from 8, is composed of a type of protein which is not found either in the derivative of soy or in food of animal origins. It contains no fat, nor cholesterol - if we except the good cholesterol of extra virgin olive oil - or carbohydrates, resulting therefore be an ideal food for diabetic and celiac people, despite coming from grain.

According to many tasters, the taste of Muscle of Wheat is strikingly similar to that of meat.

Marascio found, proportionally, a greater interest from people out of the universe of vegetarians and vegans, because very often these individuals react with surprise, admitting the goodness of food consisting exclusively on vegetable.

The invention of Marascio is truly innovative, the traditional dishes may be reformulated without significant changes, as it is not the case with traditional seitan, tempeh, soy nuggets, tofu, that frequently require an additional food that gives them flavor. In addition, this food is not derived from soy beans, whose massive use, especially by some vegans, is currently the subject of frequent discussions, but from veggie products traditionally adopted in Italy - in particular, the grain used to produce “Muscle of Wheat” belongs to the “cultivar Senatore Cappelli”, renowned for its nutritional qualities (see Seclì, 2007).

| Figure 5. Image of Muscle of Wheat dish: “arrosto con verdure” |

|---|

|

| Source: Muscolo di Grano (n.d.) |

| Figure 6. Image of Muscle of Wheat dish: “Muscolo di Grano alla Pizzaiola” |

|---|

|

| Source: Muscolo di Grano (n.d.) |

| Figure 7. Image of Muscle of Wheat dish: roast beef |

|---|

|

| Source: Muscolo di Grano (n.d.) |

Muscle of Wheat Wins the Oscar Green Prize at Expo Milan 2015

Muscle of Wheat wins the first prize in the category WeGreen in the occasion of the national competition Oscar Green at Expo Milan, in Italy, as the best and original truly innovative food (see Figure 8, Figure 9). The victory of Muscle of Wheat represents an historical steps towards the production of eco-sustainable food, because it stimulates world's attention upon a product that will solve many problems, both ethical and healthy, for generations to come. The population is increasing exponentially and consequently, to meet the protein need, we see an unsustainable adoption of intensive farming, at the expense, of course, of the quality and ethical issues. Intensive farming goes against nature, by modifying the natural cycles of growth of animals, all with the addition of hormones that, as a result, we assimilate by feeding. Muscle of wheat, contains all the necessary proteins, right calories, zero carbohydrates and zero saturated fat, does not intend to eliminate meat, but stands as an alternative food, at least in the days that you want to save a bit your body, and especially our liver (see Napolitano, 2015).

| Figure 8. Muscle of Wheat wins Oscar Green 2015 |

|---|

|

| Source: Oscar Green (2015) |

| Figure 9. Muscle of Wheat wins Oscar Green 2015 |

|---|

|

| Source: Napolitano, U. (2015) |

In this chapter the authors propose the possible agreement among a large globalized food producer and Muscle of Wheat. We think that Muscle of Wheat cannot enter a global market without the help of a large food producer already in the market, for example like McDonald's or other globalized food chains. At this aim, we propose a game theory model based on a coopetitive reasoning, representing a possible asymmetric R&D alliance between two subjects: McDonald's and Muscle of Wheat. This asymmetric alliance will benefit different players in the game, Muscle of Wheat will enter a globalized market and export its production worldwide, McDonald's will gain another part of the global food market and society will gain from health improvement.

The Economic Model

Semi-Quantitative Description of the Payoffs

At the end of this R&D alliance, the benefits for the three partners can be summarized as follows:

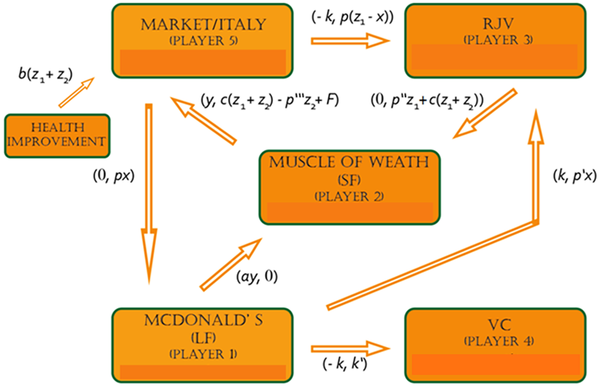

The Formal Construction of the Game Model

The players are:

The authors distinguish between principal players and side players: principal players are LF and SF, side players are RJV, VC and the Market (civil society).

Strategies

We assume that:

In other terms, we shall use the strategy z of the 3rdplayer as a cooperative strategy of the couple (LF, SF) in a coopetitive game.

Payoffs

Axiom 6: The payoff function of McDonald’s is defined by

f1(x, y, z) = (p - p')x - k' - ay,

where:

Axiom 7: The payoff function of MW is defined by

f2(x,y,z) = p''z1 + ay - y - F + p''' z2,

where:

Axiom 8: The payoff function of the RJV is defined by

f3(x,y,z) = p'x + p(z1 - x) - cz1 - p''z1 -cz2;

where:

Axiom 9: The payoff function of VC is defined by

f4(x,y,z) = k' - k

where:

Axiom 10: The payoff function of the Market is defined by

f5(x,y,z) = - p(z1 - x) + cz1 + k - px +y + bz1+ cz2 -p'''z2 + bz2

where:

The following Figure 10 shows the formal situation.

| Figure 10. Formal representation of the game |

|---|

|

Economic Interpretation

When the research of the RJV of the good (in our case the food) has already begun, then the production of sustainable food is conducted by 2nd player and the Large Firm decides the amount x of production to buy from the RJV.

To begin the RJV research, the VC offers a financial support k to RJV, to cover the initial sunk costs.

After the cooperative production of 2nd player is started, the 1st player pays the capitalized sunk costs k'>k to the RJV, in order to compensate the VC and to conclude the participation of the VC in the game.

Moreover, at the beginning of the RJV, 1st player funds directly the researches of the small firm SF, by a sum ay, for any investment y in research of the 2nd player, with a > 1.

Revenues for the 2nd player are equal to

p''z1 + p'''z2,

where:

The cost is represented by the investment for research and is equal to y.

Axiom 16: For the Research Joint Venture revenues are calculated as

p'x + p(z1 - x) + k

where:

Axiom 17: Lastly, the authors assume that the cost cz for the production of z (by the second player) is paid by the RJV and so the costs for the RJV are equal to:

cz1+ cz2 + p''z1 + k,

where:

Once defined numerically the Payoff functions and strategies of the players, we can develop and analyze completely the numerical game and find classic and less classic solutions of the game: from a competitive, cooperative and coopetitive perspectives. As usual, such solutions show specific economic meanings.

Specifically, we suggest to analyze the game following the general lines proposed by David Carfì in his complete analysis of a differentiable game.

Complete analysis of differentiable game consists in the following points of exam:

In the present work, we do not analyze completely the game but we propose a complete, general and detailed economic model. For some examples, of similar economic models, completely studied by using the technic of a differentiable game completely analysis, you can find in Baglieri, Carfì and Dagnino (2016a, 2016b, 2012), Carfì and Donato (in press), Carfì and Lanzafame (2013), Carfì and Musolino (2015a, 2015b, 2014a, 2014b, 2013a, 2013b, 2013c, 2012a, 2012b, 2012c, 2012d, 2012e, 2011a, 2011b), Carfì and Romeo (2015), and Carfì and Schilirò (2014a, 2014b, 2013, 2012a, 2012b, 2012c, 2012d, 2012e, 2011a, 2011b, 2011c, 2011d).

In particular, we want to emphasize the following solution points:

Remark

Maximum-collective solutions consists in finding a compromise maximum collective gain solution (if any) and in sharing fairly the corresponding total profit.

The share of collective gains among players can respect the Kalai-Smorodinsky method.

Sharing the maximum collective profit by using a Kalai-Smorodinsky method allows to obtain a win-win solution, in the sense that, our solution will be better than the initial Nash payoff for both players.

Future and Emerging Trend

It appears now clear, without any possible doubt, that the world future of feeding goes towards non-meat and non-seafood consumption, essentially because of global environmental issues, linked with a severe climate change and an exponential growing of the current mass extinction. The food production and veggie-products, feasible for that new future feeding scenarios, reveals perfectly matching the Marascio's production of the Muscle of Wheat. Our research and solutions proposal appears perfectly fitting the future scenarios and obliged emerging trends. This consideration provides an insight about the future of the book’s theme from the perspective of the chapter focus.

From an economic point of view, the viability of the proposed paradigm and model is shown by the already employed successful similar R&D alliances in biopharmaceutical industry. The implementation issues of the proposed program might be devised in the difficulties of proposing new feeding habits to an entire society. But, as we explained before, the right way - from an economical, political, health, environmental, ethical and social points of view - appears the road which we traced.

Future Research Opportunities within the Domain of the Topic

Our economic model allows to find easily the optimal transferable utility solutions for the two main participants, when the real data come into the arena. In the future we shall consider numerical models and computer simulations for realistic case, considering also probabilistic scenarios.

As we said above, knowing the data relative to the economic problem, that is:

it becomes possible to analyze and solve the game by calculating all the Carfì's solutions and - among all - those solutions of cooperative nature that give to the main players the optimal solution on a rich Pareto boundary.

We recall two fundamental aspects of our approach:

Another possible future research consists in the observation that our model allows us to forecast, at the beginning of the game, the future gains in the case of uncertain selling scenarios, that is, we can consider scenarios in which we don't know how much product will be bought by the Market and only a part of the total production is actually sold. We shall introduce parameters indicating what percentages of production is actually sold. Such complete approach could be found in Carfì and Donato (in press).

More, assuming the existence of probability distributions on the space of possible sold production we can calculate the aleatoric variable representing the uncertain gains in function of the selling parameters.

In this chapter, we propose a possible coopetitive agreement among a large globalized food producer/seller and Muscle of Wheat, a small, local but strongly innovative healthy food producer of southern Italy.

We think that the small enterprise Muscle of Wheat cannot enter significantly a global market, without the help of a large and famous food producer, already in the global market: for example, McDonald's or other globalized food chains.

On the other hand, we strongly believe that Muscle of Wheat should enter the globalized market because of the quality of its food innovation, which is capable to address global issues such as climate change and even the current mass extinction, human-determined and linked with the extreme soil exploitation, due to all the necessities induced by the meat industry, for the feeding of animals.

Muscle of wheat represents an extremely good alternative to meat and seafood, with optimal healthy features and a minimal environmental impact.

Moreover, McDonald's might see great motivations to change towards the vegan and vegetarian productions, because the world food politics are changing in those directions.

At this aim, we propose a game theory model based on a coopetitive reasoning, representing a possible asymmetric R&D alliance between two subjects: McDonald's and Muscle of Wheat.

This asymmetric alliance will benefit different players in the game:

In this chapter, specifically, we use D. Carfì’s new coopetitive game definition, which considers both collaboration and competition together and simultaneously. Coopetition may advance the understanding and control of asymmetric R&D alliances, those between small (and/or young) firms and large (e.g. Multinational Enterprises).

The results of the mathematical study has proved that we can find more solutions advantageous both for the firms involved for the

The mathematical solution we propose are:

Our contribution is twofold:

So, we encourage McDonald’s and other large food companies to look more closely at the model to understand that compete with biological and vegan small producers and innovators is not always the right way to “get rich” and to create wealth.

From an Economic point of view, we are sure that the competition is not the right way to have success.

Food enterprises should decide not to “fight” with other small food companies to grab a good share of the market, but they have to cooperate to reach the maximum collective gain, for them and for the social communities. Indeed, it's important, for a world looking to the future, to study what is the best combination of richness for enterprises and welfare for the community and for our planet.

Our study, as it is presented, is fully applicable. It can be surely implemented by other scholars and entrepreneurs interested in the food area, and/or in living conditions of all humans and/or in sustainable food production.

Surely, the model can be improved by widening the points of view, for example by studying not only a particular global food producer and only one innovators, but taking into account entire firm-clusters, by using other innovative vegan food resources, that - during time - could be discovered.

If we want to live all in good conditions, we'll have to be more smart and more “green” to save our life and our future and so we hope that enterprises should think the same to increase world health conditions and welfare.

Nowadays, we also need that McDonald’s and other food companies should use more sustainable vegan food product, in order to use less primary resources; so we're looking to stimulate more interest on these global issues.

This research was previously published in Sustainable Entrepreneurship and Investments in the Green Economy edited by Andrei Jean Vasile and Domenico Nicolò, pages 100-143, copyright year 2017 by Business Science Reference (an imprint of IGI Global).

The authors wish to thank two anonymous referees for their precious and stimulating remarks about the work, which help to improve significantly the subject matter and the form of the present chapter.

AdnKronos. (2015). Ecco il ‘muscolo di grano’, la carne vegetale nata per amore. Focus. Retrieved April 9, 2015, from http://www.focus.it/ambiente/ecologia/ecco-il-muscolo-di-grano-la-carne-vegetale-nata-per-amore

Agreste, S., Carfì, D., & Ricciardello, A. (2012). An algorithm for payoff space in C1 parametric games. Applied Sciences, 14, 1-14. Retrieved from http://www.mathem.pub.ro/apps/v14/A14-ag.pdf

Albanesi, R. (2013). Muscolo di grano. Retrieved from http://www.albanesi.it/alimentazione/cibi/muscolo.htm

Albert, S. (1999). E-commerce Revitalizes Co-opetition. Computerworld , 33(15), 36.

Alvarez, S. A., & Barney, J. B. (2001). How Entrepreneurial Firms Can Benefit from Alliances with Large Partners. The Academy of Management Executive , 15(1), 139–148. doi:10.5465/AME.2001.4251563

AMP. (n.d.). Veganism. Retrieved from http://www.abbotsmillproject.co.uk/what-we-do/veganism/

Animalvibe. (2015). Muscolo di grano. Retrieved September 23, 2015, from http://animalvibe.org/2015/09/muscolo-di-grano/

Arthanari, T., Carfì, D., & Musolino, F. (2015). Game Theoretic Modeling of Horizontal Supply Chain Coopetition among Growers. International Game Theory Review, 17(2). doi:.10.1142/S0219198915400137

Asch, S. E. (1952). Social Psycology . Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall. doi:10.1037/10025-000

Aubin, J. P. (1997). Mathematical Methods of Game and Economic Theory (Revised Edition). North-Holland.

Aubin, J. P. (1998). Optima and Equilibria. Springer Verlag. doi:10.1007/978-3-662-03539-9

Baglieri, D., Carfì, D., & Dagnino, G. (2010). Profiting from Asymmetric R&D Alliances: Coopetitive Games and Firms' Strategies. In Proceedings of 4th Workshop on Coopetition Strategy “Coopetition and Innovation”. doi:10.13140/RG.2.1.2072.9043

Baglieri, D., Carfì, D., & Dagnino, G. (2016a). A Coopetitive Game Model for Asymmetric R&D Alliances within a generalized “Reverse Deal”. Aracne editrice.

Baglieri, D., Carfì, D., & Dagnino, G. (2016b). Asymmetric R&D Alliances in the Biopharmaceutical Industry. International Studies of Management & Organization , 46(2(3)), 179–201. doi:10.1080/00208825.2016.1112154

Baglieri, D., Carfì, D., & Dagnino, G. B. (2012a). Asymmetric R&D Alliances and Coopetitive Games. In Advances in Computational Intelligence: 14th International Conference on Information Processing and Management of Uncertainty in Knowledge-Based Systems, IPMU 2012, Proceedings, Part IV. Springer-Verlag. 10.1007/978-3-642-31724-8_64

Baglieri, D., Carfì, D., & Dagnino, G. B. (2012b). Asymmetric R&D Alliances and Coopetitive Games. Cornell University Library. Retrieved from http://arxiv.org/abs/1205.2878 doi:10.1007/978-3-642-31724-8_64

Baum, J. A. C., Calabrese, T., & Silverman, B. S. (2000). Dont Go It Alone: Alliance Network Composition and Startups Performance in Canadian Biotechnology. Strategic Management Journal , 21(3), 267–294.

Bengtsson, M., & Kock, S. (2014). Coopetition-Quo Vadis? Past Accomplishments and Future Challenges. Industrial Marketing Management , 43(2), 180–188. doi:10.1016/j.indmarman.2014.02.015

Biondi, Y., & Giannoccolo, P. (2012). Complementarities and Coopetition in Presence of Intangible Resources: Industrial Economic and Regulatory Implications. Journal of Strategy and Management , 5(4), 437–449. doi:10.1108/17554251211276399

Böll-Stiftung, H. (2014). Meat Atlas. Fact and figures about the animals we eat. Friends of the Earth Europe. Retrieved January 9, 2014, from https://www.foeeurope.org/sites/default/files/publications/foee_hbf_meatatlas_jan2014.pdf

Boston University. (n.d.). Vegetarian Society. Retrieved from http://www.bu.edu/sustainability/what-you-can-do/join-a-club/vegetarian-society/

Brandenburger, A., & Stuart, H. (2007). Biform Games. Management Science , 53(4), 537–549. doi:10.1287/mnsc.1060.0591

Brandenburger, A. M., & Nalebuff, B. J. (1995). The Right Game: Use Game Theory to Shape Strategy. Harvard Business Review , 64, 57–71.

Branderburger, A. M., & Nalebuff, B. J. (1996). Coopetition . New York: Currency Doubleday.

Campbell, M., & Carfì, D. (2015). Bounded Rational Speculative and Hedging Interaction Model in Oil and U.S. Dollar Markets. Journal of Mathematical Economics and Finance , 1(1), 4–28. Retrieved from http://asers.eu/journals/jmef.html

Carayannis, E. G., & Alexander, J. (1999). Winning by Co-opeting in Strategic Government University-industry R&D Partnerships: The Power of Complex, Dynamic Knowledge Networks. The Journal of Technology Transfer , 24(2-3), 197–210. doi:10.1023/A:1007855422405

Carfì, D. (2004a). Geometric aspects of a financial evolution. Atti della Reale Accademia della Scienze di Torino , 138, 143–151.

Carfì, D. (2004b). S-bases and applications to Physics and Economics. Annals of Economic Faculty, University of Messina, 165-190.

Carfì, D. (2004c). S-linear operators in quantum Mechanics and in Economics. Applied Sciences, 6(1), 7-20. Retrieved from http://www.mathem.pub.ro/apps/v06/A06.htm

Carfì, D. (2004d). The family of operators associated with a capitalization law. Physical , Mathematical, and Natural Sciences , 81-82, 1–10. doi:doi:10.1478/C1A0401002

Carfì, D. (2006a). An S-Linear State Preference Model. Communications to SIMAI , 1, 1–4. doi:doi:10.1685/CSC06037

Carfì, D. (2006b). S-convexity in the space of Schwartz distributions and applications. Rendiconti del Circolo Matematico di Palermo, 77.

Carfì, D. (2007a). Dyson formulas for Financial and Physical evolutions in S’n. Communications to SIMAI Congress, 2, 1-10. doi:10.1685/CSC06156

Carfì, D. (2007b). S-Linear Algebra in Economics and Physics. Applied Sciences, 9, 48-66. Retrieved from http://www.mathem.pub.ro/apps/v09/A09-CA.pdf

Carfì, D. (2008a). Optimal Boundaries for Decisions. Physical , Mathematical, and Natural Sciences , 86(1), 1–11. doi:doi:10.1478/C1A0801002

Carfì, D. (2008b). Superpositions in Prigogine’s approach to irreversibility for Physical and Financial applications. Physical, Mathematical, and Natural Sciences, 86(S1), 1-13. doi:10.1478/C1S0801005

Carfì, D. (2008c). Structures on the space of financial events. AAPP | Physical . Mathematical, and Natural Sciences , 86(2), 1–13. doi:doi:10.1478/C1A0802007

Carfì, D. (2009a). Decision-Form Games. In Communications to SIMAI Congress - Proceedings of the 9th Congress of SIMAI, the Italian Society of Industrial and Applied Mathematics. doi:10.1685/CSC09307

Carfì, D. (2009b). Differentiable Game Complete Analysis for Tourism Firm Decisions. Proceedings of the 2009 International Conference on Tourism and Workshop on Sustainable Tourism within High Risk Areas of Environmental Crisis. Retrieved from http://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/29193/

Carfì, D. (2009c). Fibrations of financial events. Proceedings of the International Geometry Center - Prooceding of the International Conference “Geometry in Odessa 2009. Retrieved as MPRA Paper 31307 from http://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/31307/

Carfì, D. (2009d). Payoff space in C1-games. Applied Sciences, 11, 35-47. Retrieved from http://www.mathem.pub.ro/apps/v11/A11-ca.pdf

Carfì, D. (2009e). Globalization and Differentiable General Sum Games. Proceedings of the 3rd International Symposium “Globalization and convergence in economic thought”. Bucaresti: Editura ASE. doi:10.13140/RG.2.1.2215.8801

Carfì, D. (2010a). A model for Coopetitive Games. MPRA Paper 59633. Retrieved from http://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/59633/Carf

Carfì, D. (2010b). Topics in Game Theory . Il Gabbiano; doi:10.13140/RG.2.1.4203.9766

Carfì, D. (2010c). Decision-Form Games . Il Gabbiano. doi:10.13140/RG.2.1.1320.3927

Carfì, D. (2011a). Financial Lie groups. Proceedings of the International Conference RIGA 2011. Bucharest University. Retrieved as MPRA Paper 31303 from http://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/31303/

Carfì, D. (2011b). Financial Lie groups. Cornell University Library. Retrieved from http://arxiv.org/abs/1106.0562

Carfì, D. (2011c). Fibrations of financial events. Cornell University Library. Retrieved from http://arxiv.org/abs/1106.1774

Carfì, D. (2011d). Reactivity in Decision-form Games. Cornell University Library. Retrieved from http://arxiv.org/abs/1103.0841

Carfì, D. (2012). Coopetitive Games and Applications. In Advances and Applications in Game Theory. doi:doi:10.13140/RG.2.1.3526.6005

Carfì, D. (2015). A model for coopetitive games. Journal of Mathematical Economics and Finance , 1(1), 46–75. Retrieved from http://asers.eu/journals/jmef.html

Carfì, D., & Caristi, G. (2008). Financial dynamical systems. Differential Geometry - Dynamical Systems , 10, 71–85. Retrieved from http://www.mathem.pub.ro/dgds/v10/D10-CA.pdf

Carfì, D., Caterino, A., & Ceppitelli, R. (2015). State preference models and jointly continuous utilities . doi:10.13140/RG.2.1.3689.0966

Carfì, D., & Cvetko Vah, K. (2011). Skew lattice structures on the financial events plane. Applied Sciences, 13, 9-20. Retrieved from http://www.mathem.pub.ro/apps/v13/A13-ca.pdf

Carfì, D., & Donato, A. (in press). A critical analytic survey of an Asymmetric R&D Alliance in Pharmaceutical industry: Bi-parametric study case. Journal of Mathematical Economics and Finance .

Carfì, D., & Fici, C. (2012). The government-taxpayer game. Theoretical and Practical Research in Economic Fields, 3(1), 13-26. Retrieved from http://www.asers.eu/journals/tpref/tpref-past-issues.html

Carfì, D., & Gambarelli, G. (2015). Balancing Bilinearly Interfering Elements. Decision Making in Manufacturing and Services, 9(1), 27-49. Retrieved from https://journals.agh.edu.pl/dmms/article/view/1676/1410

Carfì, D., Gambarelli, G., & Uristani, A. (2013). Balancing pairs of interfering elements. Zeszyty Naukowe Uniwersytetu Szczeciǹskiego 760, 435-442.

Carfì, D., & Lanzafame, F. (2013). A Quantitative Model of Speculative Attack: Game Complete Analysis and Possible Normative Defenses. In M. Bahmani-Oskooee & S. Bahmani (Eds.), Financial Markets: Recent Developments, Emerging Practices and Future Prospects. Nova Science. Retrieved from https://www.novapublishers.com/catalog/product_info.php?products_id=46483

Carfì, D., & Magaudda, M. (2009). Complete study of linear infinite games. Proceedings of the International Geometry Center - Prooceding of the International Conference “Geometry in Odessa 2009”. Retrieved from http://d-omega.org/category/books-and- papers/

Carfì, D., Magaudda, M., & Schilirò, D. (2010). Coopetitive Game Solutions for the eurozone economy. Retrieved as MPRA Paper from http://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/26541/1/MPRA_paper_26541.pdf

Carfì, D., & Musolino, F. (2011a). Fair Redistribution in Financial Markets: A Game Theory Complete Analysis. Journal of Advanced Studies in Finance , 2(2(4)), 74–100.

Carfì, D., & Musolino, F. (2011b). Game Complete Analysis for Financial Markets Stabilization. In Proceedings of the 1st International On-line Conference on Global Trends in Finance (pp. 14–42). ASERS. Retrieved from http://www.asers.eu/asers_files/conferences/GTF/GTF_eProceedings_last.pdf

Carfì, D., & Musolino, F. (2012a). A coopetitive approach to financial markets stabilization and risk management. In Advances in Computational Intelligence, Part IV. 14th International Conference on Information Processing and Management of Uncertainty in Knowledge-Based Systems, IPMU 2012. 10.1007/978-3-642-31724-8_62

Carfì, D., & Musolino, F. (2012b). Game Theory and Speculation on Government Bonds. Economic Modelling, 29(6), 2417-2426. doi:10.1016/j.econmod.2012.06.037

Carfì, D., & Musolino, F. (2012c). Game Theory Models for Derivative Contracts: Financial Markets Stabilization and Credit Crunch, Complete Analysis and Coopetitive Solution. Lambert Academic Publishing. Retrieved from https://www.lap-publishing.com/catalog/details//store/gb/book/978-3-659-13050-2/game-theory-models-for-derivative-contracts

Carfì, D., & Musolino, F. (2012d). A game theory model for currency markets stabilization. University Library of Munich. Retrieved from https://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/39240/

Carfì, D., & Musolino, F. (2012e). Game theory model for European government bonds market stabilization: a saving-State proposal. University Library of Munich. Retrieved from https://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/39742/

Carfì, D., & Musolino, F. (2013a). Credit Crunch in the Euro Area: A Coopetitive Multi-agent Solution. In Multicriteria and Multiagent Decision Making with Applications to Economic and Social Sciences: Studies in Fuzziness and Soft Computing, 305, 27-48. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-35635-3_3

Carfì, D., & Musolino, F. (2013b). Game Theory Appication of Monti's Proposal for European Government Bonds Stabilization. Applied Sciences, 15, 43-70. Retrieved from http://www.mathem.pub.ro/apps/v15/A15-ca.pdf

Carfì, D., & Musolino, F. (2013c). Model of Possible Cooperation in Financial Markets in Presence of Tax on Speculative Transactions. Physical , Mathematical, and Natural Sciences , 91(1), 1–26. doi:doi:10.1478/AAPP.911A3

Carfì, D., & Musolino, F. (2014a). Dynamical Stabilization of Currency Market with Fractal-like Trajectories. Scientific Bulletin of the Politehnica University of Bucharest, Series A-Applied Mathematics and Physics, 76(4), 115-126. Retrieved from http://www.scientificbulletin.upb.ro/rev_docs_arhiva/rezc3a_239636.pdf

Carfì, D., & Musolino, F. (2014b). Speculative and Hedging Interaction Model in Oil and U.S. Dollar Markets with Financial Transaction Taxes. Economic Modelling , 37, 306–319. doi:10.1016/j.econmod.2013.11.003

Carfì, D., & Musolino, F. (2015a). A Coopetitive-Dynamical Game Model for Currency Markets Stabilization. Physical , Mathematical, and Natural Sciences , 93(1), 1–29. doi:doi:10.1478/AAPP.931C1

Carfì, D., & Musolino, F. (2015b). Tax Evasion: A Game Countermeasure. AAPP | Physical . Mathematical, and Natural Sciences , 93(1), 1–17. doi:doi:10.1478/AAPP.931C2

Carfì, D., Musolino, F., Ricciardello, A., & Schilirò, D. (2012). Preface: Introducing PISRS. AAPP | Physical, Mathematical, and Natural Sciences, 90. doi:10.1478/AAPP.90S1E1

Carfì, D., Musolino, F., Schilirò, D., & Strati, F. (2013). Preface: Introducing PISRS (Part II). AAPP | Physical, Mathematical, and Natural Sciences, 91. doi:.91S2E110.1478/AAPP

Carfì, D., & Okura, M. (2014). Coopetition and Game Theory. Journal of Applied Economic Sciences, 9, 457-468. Retrieved from http://cesmaa.eu/journals/jaes/files/JAES_2014_Fall.pdf#page=123

Carfì, D., Patanè, G., & Pellegrino, S. (2011). Coopetitive Games and Sustainability in Project Financing. In Moving from the Crisis to Sustainability: Emerging Issues in the International Context, (pp. 175-182). Franco Angeli. Retrieved from http://www.francoangeli.it/Ricerca/Scheda_libro.aspx?CodiceLibro=365.906

Carfì, D., & Perrone, E. (2011a). Asymmetric Bertrand Duopoly: Game Complete Analysis by Algebra System Maxima. In Mathematical Models in Economics, (pp. 44-66). ASERS Publishing House. Retrieved from http://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/35417/

Carfì, D., & Perrone, E. (2011b). Game Complete Analysis of Bertrand Duopoly. Theoretical and Practical Research in Economic Fields, 2. Retrieved from http://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/31302/

Carfì, D., & Perrone, E. (2011c). Game Complete Analysis of Bertrand Duopoly. In Mathematical Models in Economics, (pp. 22-43). ASERS Publishing House. Retrieved from http://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/31302/

Carfì, D., & Perrone, E. (2012a). Game complete analysis of symmetric Cournout duopoly. University Library of Munich. Retrieved from http://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/ 35930/

Carfì, D., & Perrone, E. (2012b). Game Complete Analysis of Classic Economic Duopolies. Lambert Academic Publishing. Retrieved from https://www.lap-publishing.com/catalog/details//store/ru/book/978-3-8484-2099-5/game-complete-analysis-of-classic-economic-duopolies

Carfì, D., & Perrone, E. (2013). Asymmetric Cournot Duopoly: A Game Complete Analysis. Journal of Reviews on Global Economics , 2, 194–202. doi:doi:10.6000/1929-7092.2013.02.16

Carfì, D., & Pintaudi, A. (2012). Optimal Participation in Illegitimate Market Activities: Complete Analysis of 2 Dimimensional Cases. Journal of Advanced Research in Law and Economics, 3, 10-25. Retrieved as MPRA Paper from at https://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/37822/

Carfì, D., & Ricciardello, A. (2009). Non-reactive strategies in decision-form games. Physical , Mathematical, and Natural Sciences , 87(2), 1–12. doi:doi:10.1478/C1A0902002

Carfì, D., & Ricciardello, A. (2010). An algorithm for payoff space in C1 Games. Physical , Mathematical, and Natural Sciences , 88(1), 1–19. doi:doi:10.1478/C1A1001003

Carfì, D., & Ricciardello, A. (2011a). Topics in Game Theory . Il Gabbiano. doi:10.13140/RG.2.1.2368.9685

Carfì, D., & Ricciardello, A. (2011b). Mixed extensions of decision-form games. Cornell University Library. Retrieved from http://arxiv.org/abs/1103.0568

Carfì, D., & Ricciardello, A. (2012a). Algorithms for Payoff Trajectories in C1 Parametric Games. In Advances in Computational Intelligence: 14th International Conference on Information Processing and Management of Uncertainty in Knowledge-Based Systems. Springer-Verlag. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-31724-8_67

Carfì, D., & Ricciardello, A. (2012b). Topics in Game Theory. Balkan Society of Geometers. Retrieved from http://www.mathem.pub.ro/apps/mono/A-09-Car.pdf

Carfì, D., & Ricciardello, A. (2013a). An Algorithm for Dynamical Games with Fractal-Like Trajectories. In Fractal Geometry and Dynamical Systems in Pure and Applied Mathematics II: Fractals in Applied Mathematics. PISRS 2011 International Conference on Analysis, Fractal Geometry, Dynamical Systems and Economics. 10.1090/conm/601/11961

Carfì, D., & Ricciardello, A. (2013b). Computational representation of payoff scenarios in C1 families of normal-form games. Uzbek Mathematical Journal, 1, 38-52. Retrieved from https://www.researchgate.net/publication/259105575_Computational_representation_of_payoff_scenarios_in_C1-families_of_normal-form_games

Carfì, D., & Romeo, A. (2015). Improving Welfare in Congo: Italian National Hydrocarbons Authority Strategies and its Possible Coopetitive Alliances with Green Energy Producers. Journal of Applied Economic Sciences , 10(4), 571–592. Retrieved from http://cesmaa.eu/journals/jaes/files/JAES_summer%204(34)_online.pdf

Carfì, D., & Schilirò, D. (2011a). Coopetitive Games and Global Green Economy. In Moving from the Crisis to Sustainability: Emerging Issues in the International Context. Retrieved as MPRA Paper from http://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/32035/

Carfì, D., & Schilirò, D. (2011b). Crisis in the Euro Area: Coopetitive Game Solutions as New Policy Tools. Theoretical and Practical Research in Economic Fields, 2(1), 23-36. Retrieved as MPRA Paper from http://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/27138/

Carfì, D., & Schilirò, D. (2011c). Crisis in the Euro Area: Co-opetitive Game Solutions as New Policy Tools. In Mathematical Models in Economics, (pp. 67-86). ASERS. Retrieved from http://www.asers.eu/asers-publishing/collections.html

Carfì, D., & Schilirò, D. (2011d). A model of coopetitive games and the Greek crisis. Cornell University Library. Retrieved from http://arxiv.org/abs/1106.3543

Carfì, D., & Schilirò, D. (2012a). A coopetitive Model for the Green Economy. Economic Modelling, 29(4), 1215-1219. doi:10.1016/j.econmod.2012.04.005

Carfì, D., & Schilirò, D. (2012b). A Framework of coopetitive games: Applications to the Greek crisis. Physical , Mathematical, and Natural Sciences , 90(1), 1–32. doi:doi:10.1478/AAPP.901A1

Carfì, D., & Schilirò, D. (2012c). A Model of Coopetitive Game for the Environmental Sustainability of a Global Green Economy. Journal of Environmental Management and Tourism, 3(1), 5-17. Retrieved as MPRA Paper from https://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/38508/

Carfì, D., & Schilirò, D. (2012d). Global Green Economy and Environmental Sustainability: A Coopetitive Model. In Advances in Computational Intelligence, 14th International Conference on Information Processing and Management of Uncertainty in Knowledge-Based Systems, IPMU 2012. Springer Berlin Heidelberg. 10.1007/978-3-642-31724-8_63

Carfì, D., & Schilirò, D. (2012e). Global Green Economy and Environmental Sustainability: A Coopetitive Model. Cornell University Library. Retrieved from http://arxiv.org/abs/1205.2872

Carfì, D., & Schilirò, D. (2013). A Model of Coopetitive Games and the Greek Crisis. In Contributions to Game Theory and Management. Saint Petersburg State University. Retrieved from http://www.gsom.spbu.ru/files/upload/gtm/sbornik2012_27_05_2013.pdf

Carfì, D., & Schilirò, D. (2014a). Coopetitive Game Solutions for the Greek Crisis. In Design a Pattern of Sustainable Growth, Innovation, Education, Energy and Environment. Retrieved from http://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/54765/Carfì

Carfi, D., & Schilirò, D. (2014b). Improving Competitiveness and Trade Balance of Greek Economy: A Coopetitive Strategy Model. Journal of Applied Economic Sciences , 9(2), 211–220. Retrieved from http://www.ceeol.com/aspx/issuedetails.aspx?issueid=583d6083-2bbf-4d8c-af1f-3b5786c6e087&articleId=8c9be4cb-86d9-43f1-b555-58b8cb28bbeb

Carfì, D., & Trunfio, A. (2011). A Non-linear Coopetitive Game for Global Green Economy. In Moving from the Crisis to Sustainability: Emerging Issues in the International Context, (pp. 421-428). Franco Angeli. Retrieved as MPRA Paper from http://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/32036/

ChartsBin. (2009). Current Worldwide Annual Meat Consumption per capita. Retrieved from http://chartsbin.com/view/12730

Chen, M., & Hambrick, D. C. (1995). Speed, Stealth, and Selective Attack: How Small Firms Differ from Large Firms in Competitive Behavior. Academy of Management Journal , 38(2), 453–482. doi:10.2307/256688

Clarke-Hill, C., Li, H., & Davies, B. (2003). The Paradox of Co-operation and Competition in Strategic Alliances: Towards a Multi-Paradigm Approach. Management Research News , 26(1), 1–20. doi:10.1108/01409170310783376

Craig, W. G. (2009). Health effects of vegan diets. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition , 89(5), 1627S–1633S. doi:10.3945/ajcn.2009.26736N

Drolc, T. (2013). Education for sustainable development. EFnews. Retrieved January 10, 2013, from http://efnet.si/en/2013/01/10/education-for-sustainable-development/

Dutto, A. (2015). Muscolo di grano: la “carne” vegan inventata in Calabria sta conquistando l’Italia. La cucina italiana. Retrieved October 28, 2015, from http://www.lacucinaitaliana.it/news/trend/muscolo-di-grano-carne-vegetale/

Etica Vegana. (2016). Muscolo di grano. Retrieved from http://eticavegana.it/index.php?route=product/category&path=59

FAO - Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. (n.d.). Sustainable food consumption and production. Retrieved from http://www.fao.org/ag/ags/sustainable-food-consumption-and-production/en/

Fiala, N. (2008). Meeting the demand: An estimation of potential future greenhouse gas emissions from meat production. Ecological Economics , 67(3), 412–419. doi:10.1016/j.ecolecon.2007.12.021

FSNC - Four Seasons Natura e Cultura. (n.d.). Retrieved from http://www.viagginaturaecultura.it

Gavin, M. L. (2014). Vegan Food Guide. TeensHealth. Retrieved March 2014, from http://kidshealth.org/teen/food_fitness/nutrition/vegan.html

Ghobadi, S., & D’Ambra, J. (2011). Coopetitive Knowledge Sharing: An Analytical Review of Literature. Electronic Journal of Knowledge Management , 9(4), 307–317.

Giambarrresi, F. (2013). La dieta vegana è per tutti? Pro e contro. Retrieved from http://www.greenstyle.it/la-dieta-vegana-e-per-tutti-pro-e-contro-50271.html

Gnyawali, D. R., & Park, B. J. R. (2009). Co-opetition and Technological Innovation in Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises: A Multilevel Conceptual Model. Journal of Small Business Management , 47(3), 308–330. doi:10.1111/j.1540-627X.2009.00273.x

Gomes-Cassares, B. (1997). Alliance Strategies of Small Firms. Small Business Economics , 9(1), 33–44. doi:10.1023/A:1007947629435

Gourmandelle. (2015). Vegetarian on a Budget | How Much Does a Vegetarian Diet Really Cost? Retrieved September 19, 2015, from http://gourmandelle.com/vegetarian-on-a-budget-cost-diet/

Gulati, R., & Higgins, M. C. (2003). Which Ties Matter When? The Contingent Effects of Interorganizational Partnerships on IPO Success. Strategic Management Journal , 24(2), 127–144. doi:10.1002/smj.287

Hagedoorn, J., Carayannis, E., & Alexander, J. (2001). Strange Bedfellows in the Personal Computer Industry: Technology Alliances between IBM and Apple. Research Policy , 30(5), 837–849. doi:10.1016/S0048-7333(00)00125-6

Hagel, J. III, & Brown, J. S. (2005). Productive Friction: How Difficult Business Partnership Can Accelerate Innovation. Harvard Business Review , 83(2), 82–91.

iVegan. (n.d.). Retrieved from http://shop.ivegan.it/28-muscolo-grano

Jorde, T. M., & Teece, D. J. (1990). Innovation and Cooperation: Implications for Competition and Antitrust. The Journal of Economic Perspectives , 4(3), 75–96. doi:10.1257/jep.4.3.75

Key, T. J., Appleby, P. N., & Rosell, M. S. (2008). Health effects of vegetarian and vegan diets. The Proceedings of the Nutrition Society , 65(1), 35–41. doi:10.1079/PNS2005481

Kjaernes, U. (2010). Sustainable Food Consumption. Some contemporary European issues. Sustainable Consumption Research Exchange. Retrieved from http://www.sifo.no/files/file76709_prosjektnotat_nr.1-2010-web.pdf

Knutson, P. (n.d.). Let’s Uncover the Truth Behind The Vegan Food Pyramid. Vegan Coach. Retrieved from http://www.vegancoach.com/vegan-food-pyramid.html

Lado, A. A., Boyd, N. G., & Hanlon, S. C. (1997). Competition, Cooperation, and the Search from Economic Rents: A Syncretic Model. Academy of Management Review , 22(1), 110–141.

Laine, A. (2002). Hand in Hand with the Enemy: Defining a Competitor from a New Perspective. Paper Presented at the EURAM Conference: Innovative Research in Management, Stockholm, Sweden.

Leitzmann, C. (2003). Nutrition ecology: the contribution of vegetarian diets. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. Retrieved from http://ajcn.nutrition.org/content/78/3/657S.long

Leitzmann, C. (2014). Vegetarian nutrition: past, present, future. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. Retrieved from http://ajcn.nutrition.org/content/early/2014/06/04/ajcn.113.071365

Lugano, M. (2012). Gli ingredienti della cucina naturale: muscolo di grano. TuttoGreen. Retrieved July 12, 2012, from http://www.tuttogreen.it/gli-ingredienti-della-cucina-naturale-muscolo-di-grano/

Lusk, J. L., & Bailey Norwood, F. (2007). Some Economic Benefits and Costs of Vegetarianism. Retrieved October 16, 2007, from http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.549.1689&rep=rep1&type=pdf

MacMillan, A. (n.d.). 14 Best Vegan and Vegetarian Protein Sources. Health Magazine. Retrieved from http://www.health.com/health/gallery/0,20718479,00.html

McKinsey & Company. (2011). The moment Is Now. Successful Pharmaceutical Alliances in Japan. Retrieved from http://www.mckinsey.com/global_locations/asia/japan/en/latest_thinking

Messina, G. (2010). The high cost of ethical eating. The Vegan RD. Retrieved January, 20, 2010, from http://www.theveganrd.com/2010/01/the-high-cost-of-ethical-eating.html

Mingolia, S. (2015). A Expo 2015, il “muscolo vegetale” made in Italy. Retrieved from http://www.econewsweb.it/it/2015/05/05/muscolo-di-grano/#.VpqaLFKR4dU

Mission 2015. (n.d.). Problems With Current Meat Production. Retrieved from http://web.mit.edu/12.000/www/m2015/2015/meat_production.html

Muscle of Wheat. (n.d.). Retrieved from http://www.muscolodigrano.com/#!page3/cee5

Muscolo di Grano. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://www.facebook.com/muscolo.digrano/photos_stream

Musolino, F. (2012). Game theory for speculative derivatives: a possible stabilizing regulatory model. Physical, Mathematical, and Natural Sciences, 90(S1), 1-19. doi:10.1478/AAPP.90S1C1

Napolitano, U. (2015). Muscolo di Grano, la carne vegetale del futuro, trionfa a Expo Milano quale unico prodotto alimentare veramente innovativo. Famiglie d’Italia. Retrieved September 27, 2015, from https://famiglieditalia.wordpress.com/2015/10/04/muscolo-di-grano-la-carne-vegetale-del-futuro-trionfa-a-expo-milano-quale-unico-prodotto-alimentare-veramente-innovativo/

National Sustainable Sales. (n.d.). What is Vegan/Vegetarian? Retrieved from http://www.nationalsustainablesales.com/vegan-vegetarian

Ngo, D. D., & Okura, M. (2008). Coopetition in a Mixed Duopoly Market. Economic Bulletin , 12(20), 1–9.

Nguyen, T. L. T., Hermansen, J. E., & Mogensen, L. (n.d.). Environmental costs of meat production: The case of typical EU pork production. Retrieved from http://www.researchgate.net/publication/251624206

Non solo Vegan. (2014). Alimentazione vegana e sostenibilità ambientale. Retrieved November 30, 2014, from http://www.nonsolovegan.it/alimentazione-vegana-e-sostenibilita-ambientale/

Ohkita, K., & Okura, M. (2014). Coopetition and Coordinated Investment: Protecting Japanese Video Games Intellectual Property Rights. International Journal of Business Environment , 6(1), 92–105. doi:10.1504/IJBE.2014.058025

Okura, M. (2007). Coopetitive Strategies of Japanese Insurance Firms: A Game-Theory Approach. International Studies of Management & Organization , 37(2), 53–69. doi:10.2753/IMO0020-8825370203

Okura, M. (2008). Why Isnt the Accident Information Shared? A Coopetition Perspective. Management Research , 6(3), 219–225. doi:10.2753/JMR1536-5433060305

Okura, M. (2009). Coopetitive Strategies to Limit the Insurance Fraud Problem in Japan. In Coopetition Strategy: Theory, Experiments and Cases (pp. 240-257). Routledge.

Okura, M. (2012). An Economic Analysis of Coopetitive Training Investments for Insurance Agents. In Advances in Computational Intelligence: 14th International Conference on Information Processing and Management of Uncertainty in Knowledge-Based Systems, IPMU 2012. Springer-Verlag. 10.1007/978-3-642-31724-8_61

One Green Planet. (n.d.). Retrieved from http://www.onegreenplanet.org/channel/vegan-food/

Oscar Green. (2015). Oscar Green 2015 WeGreen a Muscolo di Grano. Retrieved October 2, 2015, from http://www.oscargreen.it/notizie/oscar-green-2015-a-muscolo-di-grano-per-wegreen/

Padula, G., & Dagnino, G. B. (2007). Untangling the Rise of Coopetition: The Intrusion of Competition in a Cooperative Game Structure. International Studies of Management & Organization , 37(2), 32–53. doi:10.2753/IMO0020-8825370202

Pesamaa, O., & Eriksson, P. E. (2010). Coopetition among Nature-based Tourism Firms: Competition at Local Level and Cooperation at Destination Level. In Coopetition: Winning Strategies for the 21st Century. Edward Elgar Publishing.

Petroff, A. (2015). Processed meat causes cancer, says WHO. CNNMoney (London). Retrieved October 26, 2015, from http://money.cnn.com/2015/10/26/news/red-meat-processed-cancer-world-health-organization/

Pimentel, D., & Pimentel, M. (2003). Sustainability of meat-based and plant-based diets and the environment. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition , 78, 660S–663S. Retrieved from http://ajcn.nutrition.org/content/78/3/660S.full

Porter, M. (1985). Competitive Advantage. Creating and Sustaining Superior Performance . New York: Free Press.

Quintana-Garcia, C., & Benavides-Velasco, C. A. (2004). Cooperation, Competition, and Innovative Capability: A Panel Data of European Dedicated Biotechnology Firms. Technovation , 24(12), 927–938. doi:10.1016/S0166-4972(03)00060-9

Rodrigues, F., Souza, V., & Leitao, J. (2011). Strategic Coopetition of Global Brands: A Game Theory Approach to Nike + iPod Sport Kit Co-branding. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Venturing , 3(4), 435–455. doi:10.1504/IJEV.2011.043387

Sacchi Hunter, E. (n.d.). Muscolo di grano. Cure Naturali. Retrieved from http://www.cure-naturali.it/muscolo-di-grano/4188

Saint Louis, C. (2015). Meat and Cancer: The W.H.O. Report and What You Need to Know. The New York Times. Retrieved October 26, 2015, from http://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2015/10/26/health/meat-cancer-who-report.html?_r=2

Sakakibara, K. (1993). R&D Cooperation among Competitors: A Case Study of the VLSI Semiconductor Research Project in Japan. Journal of Engineering and Technology Management , 10(4), 393–407. doi:10.1016/0923-4748(93)90030-M

Sakakibara, M. (1997). Heterogeneity of firm capabilities and cooperative research and development: An empirical examination of motives. Strategic Management Journal , 18(S1), 143–164.

Sclaunich, G. (2015). La Regione Calabria punta sul muscolo di grano per Expo. Veggo anch’io. Retrieved April 10, 2015, from http://veggoanchio.corriere.it/2015/04/10/expo-muscolo-di-grano-regione-calabria/

Seclì, R. (2007). VEG-ECONOMY. Fondamenti, realtà e prospettive dell’impresa “senza crudeltà”. Retrieved from http://www.societavegetariana.org/site/uploads/570e7bd1-6289-f2b9.pdf

Shanker, D. (2015). The US meat industry’s wildly successful, 40-year crusade to keep its hold on the American diet. Retrieved October 22, 2015 from http://qz.com/523255/the-us-meat-industrys-wildly-successful-40-year-crusade-to-keep-its-hold-on-the-american-diet/

Shy, O. (1995). Industrial Organization: Theory and Applications . Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

Società Scientifica di Nutrizione Vegetariana. (n.d.). Retrieved from http://www.scienzavegetariana.it/

Staying Vegan. (2010). Is eating vegan more expensive than a “normal” diet? Retrieved April 26, 2010, from http://stayingvegan.com/2010/04/is-eating-vegan-more-expensive-than-a-normal-diet/

Stein, H. D. (2010). Literature Overview on the Field of Co-opetition. Verslas: Teorija ir Praktika, 11(3), 256-265.

Stiles, J. (2001). Strategic Alliances, in Rethinking Strategy. Sage Publications.

Stuart, T. E. (2000). Interorganizational Alliances and the Performance of Firms: A Study of Growth and Innovation Rates in High-technology Industry. Strategic Management Journal , 21(8), 791–811.

Sun, S., Zhang, J., & Lin, H. (2008). Evolutionary Game Analysis on the Effective Co-opetition Mechanism of Partners within High Quality Pork Supply Chain. Service Operations and Logistics, and Informatics, 2008, IEEE/SOLI 2008. IEEE International Conference on, (pp. 2066-2071). IEEE.

The Vegan Society. (n.d.). Why go vegan? Retrieved from https://www.vegansociety.com/try-vegan/why-go-vegan

The Vegetarian Resource Group. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://www.vrg.org/nutshell/market.htm

Thomas, K. (n.d.). Dairy sustainability made me rethink being vegan. Dairy Council of Utah & Nevada. Retrieved from http://thecowlocale.com/2014/04/22/dairy-sustainability-made-me-rethink-being-vegan/

Turnbull, S. (2015). How to eat vegan at any restaurant (and not order salad). Retrieved June 22, 2015, from http://itdoesnttastelikechicken.com/2015/06/22/eat-vegan-restaurant-order-salad/

Universo Vegano. (n.d.). Retrieved from http://www.universovegano.it/

Vegan Outreach. (2014). What Do Vegans Eat? Retrieved from http://veganoutreach.org/what-to-eat/

Vegan Starter Kit. (n.d.). Eating. Retrieved from http://vegankit.com/eat/

Veganblog. (2015). Muscolo di grano sbriciolato. Ricette di Terra. Retrieved December 22, 2015, from http://www.veganblog.it/2015/12/22/muscolo-di-grano-sbriciolato/

Vegans of Color. (2009). Does being vegan cost more money? Retrieved February, 20, 2009, from https://vegansofcolor.wordpress.com/2009/02/20/does-being-vegan-cost-more-money/

von Hippel, E. (1987). Cooperation between Rivals: Informal Know-how Trading. Research Policy , 16(6), 291–302. doi:10.1016/0048-7333(87)90015-1

Walker, P., Rhubart-Berg, P., Mckenzie, S., Kelling, K., & Lawrencw, R. S. (2005). Public health implications of meat production and consumption. Public Health Nutrition , 8(4), 348–356. doi:10.1079/PHN2005727

Walley, K. (2007). Coopetition: An Introduction to the Subject and an Agenda for Research. International Studies of Management & Organization , 37(2), 11–31. doi:10.2753/IMO0020-8825370201

Wheeler, L. (2015). Vegan diet best for planet. The Hill. Retrieved May 4, 2015, from http://thehill.com/regulation/237767-vegan-diet-best-for-planet-federal-report-says

WHO. (2015). Q&A on the carcinogenicity of the consumption of red meat and processed meat. Retrieved October, 2015, from http://www.who.int/features/qa/cancer-red-meat/en/

Whole Foods Market. (n.d.). Retrieved from http://www.wholefoodsmarket.com/healthy-eating/special-diets/vegan

Wick, A. (2011). The Conscious Case Against Veganism. Ecosalon. Retrieved March 17, 2011, from http://ecosalon.com/reasons-not-to-be-vegan/

Wilkinson, I., & Young, L. (2002). On Cooperating: Firms, Relations and Networks. Journal of Business Research , 55(2), 123–132. doi:10.1016/S0148-2963(00)00147-8

Worldwatch Institute. (2004). Is Meat Sustainable? World Watch Magazine, 17(4). Retrieved from http://www.worldwatch.org/node/549

Zanni, M. (2013). Il Muscolo di grano: una valida e gustosa alternativa alla carne. Saggi e Assaggi. Retrieved January 30, 2013, from http://www.saggieassaggi.it/il-muscolo-di-grano-una-valida-e-gustosa-alternativa-alla-carne/