CHAPTER 5

ALL CREATURES GREAT AND SMALL (AND COLD)

Mean Wolf!

Mean Wolf!

The World of Ice and Fire has gone to the dogs. Actually, to be more accurate, it has gone to the wolves: the dire wolves. This is especially true once you get north of Castle Black, beyond the Wall, where they’re everywhere. Worse still, these ferocious creatures are about the size of a small horse, and would think nothing of ripping off your arm and then beating you to death with the bloody end. The only good news is that they tend to stay in the furthest reaches of the North in the Lands of Always Winter, with Theon Greyjoy noting that the dire wolves haven’t been seen south of the Wall for hundreds of years.

The Stark children, Sansa and Bran, Rob and Arya, Rickon and Jon Snow, find a litter of orphaned dire wolf puppies and are desperate to keep them–like all children everywhere when confronted with the cute, mewling faces of slavering ferocious death beasts in their juvenile form. Their father Ned gives them a lecture worthy of any parent in Pets R Us along the lines of ‘Ok then but you’ll have to walk them yourselves even if it’s raining’. And it rains a lot in the North. Let us remember, Ned Stark is not a man known for his wise decisions, but this may be one of his better ones.

Dire wolves (canis dirus–Latin for ‘fearsome dog’) are unfortunately extinct today, but they were once real and could be found roaming the grasslands and forests of America, between 10,000 and 240,000 years ago. We know this because the fossilised remains of a staggering 3,000 dire wolves have so far been found in tar pits across California. The pits were actually pools of black, sticky asphalt that were created when crude oil seeped up from deep inside the Earth through a crack in its surface. In the last Ice Age, hundreds of these large black pits acted like vast sheets of flypaper, quickly immobilising any creature unlucky enough to venture their way.

Let’s turn back the hands of time and watch the pit in action. Imagine a woolly mammoth, out for an afternoon amble. Seeing a pool of water that has formed atop the tar, the large beast inadvertently wanders into the pit and is somewhat surprised to see its hairy feet sinking slowly and inexorably into the black goo. Panicking, the mammoth raises its trunk and trumpets in distress. Sensing an easy kill, a nearby dire wolf hears the cry for help and rushes in. Moments later, both animals find themselves stuck in the tar, both unwilling participants in what researchers now refer to as an ‘entrapment event’. Over time, the two animals start to feel strangely comfortable in one another’s company, but slowly die from a heady mixture of malnutrition and boredom.

Thanks to geologists, we know that the dire wolves of our past were roughly the same size as our modern grey wolves, though broader and more muscular–weighing in at around 25% more–and with shorter legs (which meant they were probably slower to cover distances). If a dire wolf did catch you, and you found yourself in the unlucky position of being between its jaws, the bite force of this beast was pretty hefty; it would chow down on you with 129% of the force of a modern grey wolf bite (which itself is no playful nip).

Fossil records from the tar pits also show that the dire wolf apparently lived in large groups, often took down big prey, and tended towards a facial expression consistent with ‘I can’t believe I did that. God, I’m bored’. Unlike grey wolves, they would have steered clear of the snow and ice of the oncoming winter in Game of Thrones, as they preferred temperate regions. The most recent research has revealed that the wolves died out just over 10,000 years ago, and that their demise was possibly due to stiff competition from smaller animals, with coyotes proving especially efficient at picking off their shared prey.

So there you have it. Dire wolves did indeed exist and were fierce killers. However, unlike the wolves that populate the World of Ice and Fire, they weren’t all-powerful and were eventually outsmarted by a group of well-organised and wily coyotes.

They Might be Giants?

They Might be Giants?

Mysteriously large creatures emerging from the icy darkness to hunt, pale, spindle-legged spiders bigger than your face. The creatures of Samwell Tarly’s White Walker nightmare. Welcome to… no, not the fictional Lands of Always Winter, but our own factual-but-strange world of polar gigantism!

As the realms to the north of the Wall may be alien and unknown, even frightening, to the inhabitants of Westoros, so the natural world of our own coldest places on Earth is strange to us. (Though it’s worth pointing out here that we humans have been to our North Pole and, as far we know, the only weird white-bearded guy with strange powers hanging around there is Santa Claus, not a White Walker.)

When 19th century explorers began venturing forth with scientific expeditions to the North and South poles, the creatures they encountered gave them chills, in more ways than one. For a thousand years or more, Europeans had been venturing into the Arctic Circle to hunt for whales, the leviathan of the deep. They had met curious critters that seem fantastical, like the narwhal–the unicorn of the seas with its single twisted horn growing six feet long. But even when you’re a hardy Victorian polar explorer, with glinting frost in your beard and partially digested, sadly loyal husky dog in your belly, nothing can prepare you for the sight of a squirming tide of sea spiders the size of dinner plates, all over the deck of your ship.

There are over a thousand different species of sea spiders, found all over the world, from the Caribbean to the Mediterranean. They tend to be tiny, sometimes just over a millimetre in diameter, but in the icy waters of the Antarctic they grow to over 90 centimetres. And gigantism isn’t just confined to spiders; polar bears are only found in the Arctic and are on average noticeably larger, and fiercer, than their browner, woodland-ier cousins like the Kodiak bear.

So what’s going on?

Well, the giant spiders could be benefiting from higher concentrations of oxygen in the water and air, or better quality foodstuffs in the extreme north and south (these theories are still being debated). Or they could be a result of ‘Bergmann’s Rule’, as posited by the 19th century German biologist Carl Bergmann. This is the principle that states that body mass increases in cold climates, and smaller size species are found in warmer regions. If we look back through evolution, it is true that megafauna (big animals) flourished at times when the planet was colder; and when the Earth heated up, our significantly smaller ancestors, the mammals, got their turn. Bergmann believed that it’s all down to larger animals having a lower surface area to volume ratio, so they lose less body heat per unit of mass, and therefore stay warmer in cold climates. Warmer climates impose the opposite problem: body heat generated by metabolism needs to be dissipated quickly rather than stored within.

In Game of Thrones, of course, the tallest people we encounter are a race of giants who live north of the Wall, up in the coldest part of the Known World. Could polar gigantism also work on humans? Well… yes and no. Sadly there is no race of ancient giants hiding at the snowy wastes of our Poles, North or South. Instead, the people who live close to the North Pole are actually shorter, stockier and of heavier build than their counterparts closer to the equator. This fits with Bergmann’s findings: someone of a stocky build will have a lower surface area compared to longer-limbed humans in hotter climates, which means less heat loss when it matters.

The human race is generally getting taller. We’ve grown on average four inches more since World War I ended. But the tallest nation on Earth is to be found in distinctly un-chilly Holland, with an average height of 168.7 cm (5 feet 6.4 inches) for women and 184.8 cm (6 feet 0.8 inches) for men. Researcher Gert Stulp, from the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, believes this is due to natural selection. It would seem that in Holland tall men have more children than shorter men, and are thus passing on their tallness as a heritable trait to their children. Will this go on and on, leading to a race of Flemish gargantuans, delicately stepping over windmills while munching on their boulders of Edam? (No offence, Holland.) Sadly not, as there seem to be limits to human height, beyond which the disadvantages definitely outweigh the advantages. Nevertheless, Gert Stulp intriguingly points to fossil evidence of Neanderthals discovered in Europe.

‘We tend to compare ourselves to our historical counterparts in written history–200 years ago–when we were much shorter,’ he explains. ‘But if we look at Palaeolithic records–2 million or so years ago–we do find fossils that reach heights of 190cm and that is much taller than many of the individuals in populations now. That suggests that many populations haven’t reached their evolutionary peak height… but it is difficult to say.’

(There was also a rather appealing theory doing the rounds for a while that Neanderthals’ noses may have grown rather large due to adapting to the cold, but very sadly this seems to be untrue.)

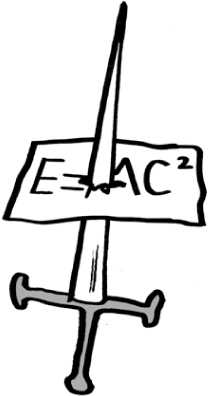

Sir Isaac Newton, Giant Killer

Sir Isaac Newton, Giant Killer

Giants like Wun Wun, who live in the extreme north of Westeros, are generally about 10 to 12 feet (3 to 3½ metres) tall, though they can grow larger in some cases. In the books they are basically double the height of a man, in the TV show even taller. They are fearsomely strong and ride mammoths as steeds. So could they exist in real life? Or is there more than a touch of magic to them?

To create one–you just need a scaled-up, really tall human, right? Easy! Well, no. The ‘scaling up’ bit is exactly where we run into difficulties in the real world, thanks to the laws of math and physics, which govern how changes in size affect things like movement and body mass.

Let’s begin with what’s known as the square-cube law, a mathematical principle that demonstrates why sizing up is a bit trickier than it first seems. Leaving aside the awkward, irregular and frankly confusing shape of a human being, let’s begin by doubling the size of a cube. If you measure the edges of a cube and then create a new cube with edges double the length of the original, a strange thing happens. Yes, sure, the size of the cube doubles just as you’d expect, but its surface area doesn’t double along with it; instead it increases fourfold, and the volume of our cube increases eightfold. (You could make a cube out of scrap paper, and then double it to see this in action, for a bonus Ad Break Science experiment.)

So, how does this apply to living creatures? Well, it’s not an exact science as we’re not dealing with regular shapes; plus, we’d want our giants to be strong and able to easily stand upright and move around, yes? Here we must turn to the mighty Sir Isaac Newton and factor in his Second Law of Motion, which states that force = mass x acceleration.

If we double the size of a human, while keeping them still roughly human-shaped, we end up with around four times the muscle power (so far so good), but that muscle power will need to move approximately eight times the mass. So this scaled-up creature is going to be only around half as strong and agile as a regular-sized human. Which means, for a start, our giant’s heart and lungs would find it hard going keeping up with an army of regular-sized wildlings.

Ah, another great plan foiled by math! But we run into this exact same problem all over the place with non-living things too. For example, it’s an issue in engineering–from steam trains to rocket engines, inventors and innovators have had to grapple with the square-cubed law when trying to improve and create bigger and better machines. And it’s also the reason skyscrapers can only get so big.

It’s a little ironic when we think of Sir Isaac’s famous and apparently modest line about his achievements: ‘If I have seen further it is by standing on the shoulders of giants.’ Yes, thank you, Newton, that’d be the giants who you’ve just helped prove couldn’t really exist then…

The Scientific Secret

The Scientific Secret

of the Giant’s Causeway

Over in the Seven Kingdoms, giants are said to have had a large (very large) hand in building the Wall. In our world, the most famous feat of engineering commonly attributed to those of taller than average stature is the Giant’s Causeway. Stretching out into the sea towards Scotland from the north-east coast of Northern Ireland, the Causeway is ‘paved’ with thousands of interlocking six-sided columns of basalt rock. By a strange quirk of geographical fate, this same breathtakingly beautiful stretch of coastline serves as a major location for Game of Thrones, with the area around the Causeway forming the backdrop to several scenes from the Iron Islands, home of Theon and the other Greyjoys.

How did the Causeway come to exist? According to folklore, an Irish giant called Finn MacCool was challenged to fight by a Scottish giant named Benandonner. There wasn’t the big money in professional fighting in those days, and in the absence of a promoter, Finn himself was forced to build a rocky road so that the two giants could meet for their epic super-enormous-weight bout. However, as with so many large-scale multi-national engineering projects conceived in the heat of the moment and fuelled by hostility, regret soon set in (see also the Channel Tunnel).

As Finn is close to completing the Causeway he gets a better view of Benandonner, and realises there’s no way he wants to fight the guy–Benandonner is considerably bigger than he looked back when they were in different countries with no convenient land bridge. So, his only option is to outsmart the mighty Scot. Enter Finn’s helpful wife Oonagh, who dresses her husband as a baby and tucks him up in a cradle (we are not told whether this is a regular feature of the MacCools’ marital life). When Benandonner sees the hulking infant he becomes fearful of the kind of giant who could father such a vast child. Tail between his giant legs, Benandonner runs back to Scotland, destroying the Causeway behind him so he can’t be followed.

So far, so fantastical.

The site was first revealed to the world in 1693, by an Irish politician, Sir Richard Bulkeley, who presented a paper on the Causeway to the esteemed members of the Royal Society in London. It has fascinated geologists ever since.

The phenomenon of distinctive hexagonal columns is seen at various–usually supernaturally-named–sites around the world, including California’s Devil’s Postpile. Years of speculation and experimentation have resulted in scientists now firmly believing that the regularly shaped basalt columns are of volcanic origin. According to this theory, around 50 to 60 million years ago (during what’s known as the Paleogene Period), the area around the Causeway was an intensely volcanic place covered with molten basalt lava. As the lava cooled it contracted, and eventually began to crack, like mud drying out on a hot day. The shrinkage caused stresses that then fractured the rock. But the strange, uncanny organisation of these cracks, or ‘joints’ as geologists call them, makes hexagonal shapes in a variety of sizes that appear very well ordered. And it is this that has led to the supernatural explanations.

On Being the Right Size

On Being the Right Size

When it comes to being a large creature, being on land or in the air is no match for the buoyancy of the ocean, which helps no end in taking the strain off internal organs, and so forth. It doesn’t really matter so much about your mass in the sea, it’s your density that counts–hence of course a small dense object like a marble will sink, whereas a huge sphere made of polystyrene will float. There’s a reason the biggest living beings on Earth are in the sea. Animals are basically made of water, so the sea is the place to be, to escape the effects of gravity. So yes, a giant merman/ mermaid? Perfectly plausible (see here for more merfolk in action).

Wherever you are, is there a ‘right’ size to be? How do animals’ relative sizes affect their lives? Why don’t you get really huge hulking mice, or really tiny elephants?

The question of appropriately large or small scale animals fascinated Indian evolutionary biologist JBS Haldane, who pondered the issue in his intriguing essay ‘On Being the Right Size’. Haldane begins by seeing off the traditional giants of children’s fairy tales, as well as more modern monsters such as King Kong or Godzilla. He posits that the storybook giants he remembers from his childhood–10 times the height of their human adversaries–would have weighed a thousand times as much as a regular human, and seeing as human thigh bones break under about 10 times the human weight, they would have snapped their legs each time they took a step. (Haldane speculates that this is why said giants were often pictured sitting down, but confesses that he has somewhat lost respect for Jack the Giant Killer’s prowess. Young Jack could’ve finished off the ‘fee fi fo fumming’ f*cker at the top of the beanstalk by asking him to stand up and say that.)

There are advantages then to being small. ‘You can drop a mouse down a thousand-yard mine shaft; and, on arriving at the bottom, it gets a slight shock and walks away, provided that the ground is fairly soft. A rat is killed, a man is broken, a horse splashes,’ says Haldane (who is beginning to sound a lot like Ramsay Bolton). But lest we fear psychopathy, Haldane explains his real interest–how the forces that buckle giants save the little mouse.

Discharged down into Haldane’s thought experiment mine shaft, your destiny upon arrival at your final destination will be very different depending on your physical form during this nightmare descent. To begin with, the mouse’s tale. If you’re a mouse, you have a larger surface area in relation to your volume–and therefore your mass–than the horse waiting nervously behind you. So as a mouse you’ll fall more slowly, for a start.

‘Divide an animal’s length, breadth, and height each by ten; its weight is reduced to a thousandth, but its surface only to a hundredth,’ states Haldane, employing our cube rule from above, this time in reverse. So, as a mouse, your physical resistance to falling is relatively ten times greater than the driving force pulling you down. Because of its size, the unfortunate horse has much more kinetic energy than the mouse so, when our (imaginary) horse meets the bottom of the (imaginary) mine, this energy has to go somewhere; it has to be ‘dissipated’ a physicist would say. So yes, it’s dissipated by–essentially–exploding everywhere.

If you really really must recreate this experiment drop a grape, then a watermelon out of a first floor window after having checked no-one is around for at least a radius of 1 mile and you can clear up the water-melon and not waste it entirely!

‘Dark Wings, Dark Words’

‘Dark Wings, Dark Words’

Message-carrying crows and ravens flock through the worlds of fantasy literature, delivering vital missives and generally moving along plots nicely. The World of Ice and Fire is no exception, of course, with the Westorosi postal system entirely reliant on these feather-based couriers to fly messages from castle to castle. Indeed, throughout the show, pivotal news arrives via ravens, often received with foreboding: ‘dark wings, dark words’, as Ned Stark memorably mutters.

The ravens are cared for, trained and dispatched by the Maesters, the postmaster-scholar-healer-scientists of the Seven Kingdoms. In ancient times, the birds could talk, but this knowledge has been lost and now they carry written-down messages attached to their legs. In principle, ravens in our world could be used to convey verbal messages. While possibly not up to learning whole missives, they are excellent mimics who can learn to talk better than some parrots. Watch, for instance, YouTube sensation and talking raven Mischief demonstrating his ability to say ‘Hello’ in a rather stern, deep voice and ‘Hi’ in the manner of an anime schoolgirl.

I digress.

Ravens have never actually carried messages for us in our world, but the idea of them as messengers has deep roots in popular culture. Myths from Tibet to Ireland have seen the raven as a messenger for the gods. The Norse warrior god, Odin, had two ravens–Hugin (thought) and Munin (memory)–who flew all over the world, collecting information and reporting back to Odin every night with their news. According to the Icelandic sagas, Odin also spent quite a while fretting about when they would actually arrive with their deliveries, muttering ‘I am worried about Hugin yet more about Munin’, before apparently adding ‘Thorsday he was late, then on Freya’s day he came not at all–but I found a card of crimson and white declaring there was “something for me” and that he had returned “while I was out”, though I had not left Aasgard these long hours and the post office of Midgard to which he referred me is only open ’til 1pm tomorrow…’

In our world, pigeons are the ones entrusted with carrying information. For years, the puzzle of how homing pigeons found their way home went unsolved. Ten years of international study by animal behaviourists at Oxford University, however, provided the answer. Apparently they simply follow our roads and highways! In 2004 Professor Tim Guildford explained the team’s surprising findings to the world’s media: ‘It really has knocked our research team sideways to find that pigeons ignore their inbuilt animal instincts and follow the road system… When they do follow a road, it’s so obvious. We followed some which flew up the Oxford bypass and even turned off at particular junctions. It’s very human-like.’

Getting to Crow You,

Getting to Crow You,

Getting to Crow All About You

Despite their tiny bird brains, there is plenty of evidence to suggest that ravens and crows are as smart as chimpanzees and dolphins, and surprisingly sophisticated when it comes to their behaviour. They are also capable of feeling empathy, and both recognise the concept of death and fear it.

But how did researchers discover this, I hear you ask? It’s a good question. They asked a flock of crows to watch the ‘The Rains of Castamere’, aka the Red Wedding episode, and counted the number of times the birds lifted their wings to cover their eyes in horror. Just kidding. Actually, the researchers noticed that crows behave ‘unusually’ around death. When a crow passes on to the great flock in the sky, members of its group have been observed crowding around the corpse, squawking loudly, which intrigued researchers and got them wondering if the birds were taking part in a funeral for their dead co-crow.

Scientists at the University of Washington in Seattle set up a crow-death experiment. Lead researcher Kaeli Swift made a good impression on a flock of crows by feeding them treats. However, capitalising on the knowledge that crows do not forget a threatening face, Swift was soon joined by a second researcher: this time an apparently dangerous individual.

As BBC Earth reported, ‘To prevent any real life harassment from crows, the face they used was not a real one but a rather realistic latex mask covering their real face.’ So there you go. In the past, in the name of acquiring new knowledge, great men and women of science have exposed themselves to dangerous levels of radiation (Marie Curie), studied optics by impaling their eye on a needle (Isaac Newton) and even kept their baby daughter in an experimental box (BF Skinner–she quite liked it, apparently). But here, finally, we see a limit being reached. No-one wants to be disliked by crows. No-one is willing to become a hate figure for the feathered community, a crow-loathed miscreant unable to step outside the lab for fear of being cawed at and heckled by a testy corvid mob. (We’ve all seen Hitchcock’s The Birds, right?)

This second researcher would ‘be holding a dead crow, not violently,’ Swift noted matter-of-factly, ‘not re-enacting a death scene, just holding it like they were picking it up to throw it in rubbish, palms outstretched like you might hold a plate of hors d’oeuvre.’ [My italics. As someone who is a fan of hors d’oeuvre, I’m not quite sure what to make of all this, other than I don’t think I would ask Swift to pass round the nibbles at parties.]

Previous research has shown that crows not only remember a threatening face, they share that knowledge within their community, so that the individual is remembered and scolded by the crows, even after a gap of several years. Young crows, it seems, are even taught to recognise and scold the ‘villain’ by their parents.

The crows did not like the bad guy in Swift’s experiment one bit; they began scolding and mobbing the masked researcher in a display of aggression, which also seemed to serve as a ‘learning to recognise’ experience for their flock. They also avoided Swift’s food. Even when the masked researcher returned the next day without the dead crow, they avoided him and the food that Swift had brought them, giving a strong indication that they recognised and feared death, according to the scientists. (Though when the experiment was repeated with a dead pigeon the crows seemed noticeably less bothered–indicating that they recognised the threat specifically to their own kind. Or that nobody–not even other birds–really likes pigeons. Even if they are good at following highways.)

In the absence of warging, science appears to bring us tantalisingly close to seeing the world through the eyes of animals. But as laypeople, we are still prone to misinterpreting our corvid friends. Ravens are one of the few animals that we believe reliably use gestures–with beak or wing–to draw the attention of fellow ravens to points of interest. And they appear capable of communicating with humans, too.

In his book Mind of the Raven, Professor Bernd Heinrich recounts a curious encounter between a human, a raven and a cougar. In rural Colorado, a woman was working outside her cabin alone when she became aware of what seemed like the increasingly urgent chattering of a raven. When the bird landed on a rock nearby she looked about her and came eye-to-eye with a cougar, poised to spring and attack her.

How would you interpret this encounter? The woman (who escaped unscathed) believes that the raven was trying to warn her that her life was in danger. Heinrich, who has spent many years studying the behaviour and culture of the birds, believes rather that the raven was identifying her as a dining opportunity for itself and the cougar, and warmly encouraging the big cat to stop wasting time and get on with it. It’s not for nothing that the collective term for a flock of ravens is ‘an unkindness’ or ‘a conspiracy’. The carrion birds were traditionally regarded as sinister; like other corvids, they would flock to battlefields to pick over the dead and dying, and of course the fourth book in the A Song of Fire and Ice series deals with the terrible aftermath of the War of the Five Kings in A Feast for Crows.

In the wild, ravens will certainly team up with other animals, including humans, for a mutually beneficial arrangement. Wolves and ravens, for example, will pair up to hunt. When wolves were reintroduced into Yellowstone National Park in the 1940s this complex attachment was observed re-establishing itself very quickly–the wolf pack was seen hunting with ravens flocking close behind. That both these creatures, wolves and ravens, have a special place in our mythology and stories, and that their behaviour still intrigues us, hints at a time when we were closer to the animal world, possibly when ravens were indeed bringing ‘messages’ of a kind.

Is it entirely fanciful that our first hunter-gatherer forebears would have recognised and followed the swooping of ravens to a kill by wolves as a way of finding food when times were hard, and that all three creatures hunted together? When you’re hungry enough, the cawing of ravens sighting meat really could seem like the most precious message from the gods.

If We Could Ride Any Animal

If We Could Ride Any Animal

Getting from place to place in the Seven Kingdoms involves a variety of four-legged transportation. Usually, as you might imagine, it’s fastest to ride a horse. But some rather more exotic creatures have been pressed into service in Westeros.

Dany, like her Targaryen ancestors, rides a dragon–initially with varying degrees of success. (She and Drogon end up making a good team, but finding dragon riders who can control the fire-made-flesh of Drogon’s siblings, Rhaegal and Viserion, seems crucial for the conquering to come.) We don’t know much about the northern, island-dwelling Skagosi–they’re a brutal people, legends say they are cannibals–but in an unexpectedly whimsical move, they trot about on unicorns. There’s Cold Hands, a kindly, enigmatic book character from north of the Wall who helps Gilly and Sam as well as Bran and the Reeds. Notably, he rocks up on the back of a large elk. And if we were to journey across the World of Ice and Fire to the eastern continent of Essos, we’d encounter the nomadic raiders Jogos Nhai, trekking across the great open plains astride their black-and-white striped equines, zorses.

So, can any animal with suitable human-sized space on its back be ridden? And in our world, why do we still ride horses, rather than, say, zebras or zorses?

Well, it’s not black and white…

We humans have been domesticating our fellow animals for about 20,000 years. And in that time, we’ve figured out there are certain common factors that make a creature comfortable to be around. They can’t be too picky about what they eat, they must be ok with breeding and bringing up their young quite swiftly in captivity, and they must have a hierarchy, so that humans can replace the top dog (or horse, or dragon). They also need to be quite calm and relatively sweet tempered. And this is where, for example, zebras don’t really earn their stripes.

Zebras–like the zorses of the Jogos Nhai–are highly unpredictable and prone to biting and kicking if they don’t like the look of you. However, at least one man in our world saw that as a challenge to be overcome. At the end of the Victorian era, if you found yourself in the smart part of London near Buckingham Palace, you might have witnessed the memorable sight of financier-turned-zoologist the second Baron Rothschild, riding along the road in a carriage pulled by four zebras. There are other reports, too, of zebras being ridden like horses. It’s just you need to be quite brave.

When Jon Snow ventures north of the Wall, he’s bewildered not only by giants twice the height of regular men, but also their mounts–mammoths. Sadly, while we have no cave paintings depicting our ancestors from prehistoric times triumphantly posing atop shaggy pachyderms, historians believe that elephants have been giving humans a lift for at least 6,000 years. They carried the invading Romans across the Thames and into Britain in AD10 (we didn’t like that one bit) and in World War II, the allies used elephants for transportation in tropical regions, where the modern vehicles of the time couldn’t traverse. Today, in peace time, elephants carry tourists around the Amber Fort in Jaipur, India.

Elephants do contradict our guidelines for domestication and as they aren’t easy to breed in captivity have been taken from the wild and trained (and ridden) by humans for millennia. We have a unique insight into this process from the ancient Indian text the Arthashastra–a Sanskrit treatise written around 2,000 years ago, which offers guidance to rulers on government and politics of state. The Arthashastra advises that ‘summer is the time to catch elephants’, and recommends seeking out a wild elephant that’s around 20 years old (presumably they are particularly easily enticed at that age–like dangling an unpaid internship in front of a newly graduated student). It goes to on to provide details of how the beasts should be trained, cared for, stabled, rested, and exercised in as kindly a way as possible–with suggested penalties for any human who doesn’t treat the elephants well. It also recommends a kind of ‘pachyderm pension’ from the treasury be set aside to look after elephants who can no longer work or be ridden to allow them to live out a peaceful, pleasant old age (not unlike our State Pension). This is perhaps why according to reports in late 2015, the Indian Supreme Court was considering a ban on elephant rides as entertainment, due to concerns about these peaceful creatures being kept in cruel, inadequate conditions.

While the sight of giants riding on mammoths may have amazed Jon Snow, there are more extraordinary sights north of the Wall. The Others, it seems, have their own unique way of navigating the Lands of Always Winter. While among the wildlings north of Castle Black, Samwell hears the horn of the Night’s Watch blown three times–three long chilling blasts which mean the White Walkers are nearby. He remembers the stories of monsters that made him shiver and squeak as a child, the descriptions of the approaching blood hungry predators riding their giant ice-spiders.

Sweet dreams…

The Strange Truth

The Strange Truth

about Zombification

An uncannily cold blue gaze shines down from the pale, impossibly wrinkled regal face and falls upon the baby. The gathered shambling hordes are silent, sensing the majestic importance of this moment. As the crowned elder reaches down to touch the child’s cheek, a transfer of ancient power is complete…

No, this is not a royal family christening but the chilling scene in Season 5 in which we finally discover the icy fate of Craster’s male children. Torn from their mother’s arms and abandoned in the woods by their deeply deadbeat dad, the baby boys are gathered up by the White Walkers, carried away to the Lands of Always Winter and transformed into chill-eyed beings of pure coldness by their new ‘family’.

The White Walkers (also known as ‘Others’) were originally a source of great mystery. What did they want? Were they really as evil and destructive as they seemed? Were they available for children’s parties? The chilling power of these cold shadowy creatures is clearly A Big Deal because we encounter it in the opening scene of both the book and the TV series. Initially the macabre horror of what we’re seeing is mysterious. Three members of the Night’s Watch stumble across the bodies of men, women and children, butchered in the snow in a clearing in the forest. The next thing, all their bodies have vanished. And then, in helpless horror, we watch as a child, previously lifeless and impaled through the heart on the branch of a tree, stands and coolly surveys the Night’s Watch with unnaturally piercing, bright blue eyes.

As the story progresses, we learn more about the supernatural White Walkers. They’re an ancient enemy, demons of ice and cold, the only enemy that matters, says Stannis. They haven’t been seen for millennia and had receded into legend. But as we enter the World of Ice and Fire, they are reappearing, and bearing down on their human prey with shocking violence.

At the Battle of Hardhome, we witness their terrifying ability to violently mutilate human beings and then resurrect them as wights–mindless thralls who will do the White Walker’s savage bidding (relentlessly, until every last part of them is used up in the macabre service of their masters). As we see to dramatic, jaw-dropping effect, these wights eventually form a huge ‘zombie’ army under the control of the Others–ruthlessly killing their fellow humans as quickly as their overlords can resurrect the fatalities and swell the ranks of their undead army still further.

The White Walkers ride gruesome living-dead zombie horses, too–all torn sinews and bloodied-spittle nostrils. So we can assume that their power also reanimates animals.

Necromancy, bringing the dead back to life and setting them up to no good, is something we read about in the Bible, and hear about from time to time throughout history. Yet no-one modern and sensible seriously thinks it’s real. Right?

Wrong!

In 1985, Harvard ethnobotanist Wade Davis published The Serpent and the Rainbow, his account of ‘an astonishing journey into the secret society of Haitian voodoo, zombis [sic] and magic’. Davis argued persuasively that zombies were both possible and real. He believed that cultural forces and beliefs framing the ingestion of special ‘zombie powders’ could produce some of the undead-esque behaviour recognisable to fans of George Romero.

According to his account, a Haitian shaman–called a bokor–would initially give the aspiring zombie a drug derived from pufferfish venom (tetrodotoxin), which would temporarily produce the ‘effects of death’–paralysis, stiffness, ‘the odour of rot’–without actually killing you. The proto-zombie could even be buried alive, so that he and others would become convinced he had experienced death, before he was ‘resurrected’ by the shaman. The zombie would then be rendered forgetful, delirious and suggestible with the administration of yet another potential toxin, this time a plant known as Datura (or more evocatively called ‘Angel’s Trumpets’).

Davis secured samples of zombie powder, but as one of the powder’s ingredients is bits of dead human tissue, he was heavily criticised for commissioning a grave robbery, to obtain the decomposed flesh of a recently buried child. In the end, his critics noted that many of his samples of zombie powder failed to contain tetrodotoxin, and even when small doses of the neurotoxin were present, it wouldn’t produce the effects described in Davis’s account. If we really want to get to the nasty truth about zombies, we have to turn to the peculiar relationship of spiders and wasps…

Zombie Spiders and Other

Zombie Spiders and Other

Body-Snatching Stories

From the White Walkers’ ice spiders as ‘big as hounds’, to the walking-dead arachnids of our world, playing host to parasitic wasp larvae, spiders play a key role in our zombie story.

Boohoo, you may think, couldn’t happen to a nicer creature.

But read on…

Some arachnids are continually engaged in a life and death battle with another type of malign creepy crawly: the parasitoid wasp. There are hundreds of thousands of types of wasp–each has its own way of being unpleasant. Here, we look to parasite wasps who build nests to rear their young inside other living creatures. Czech scientists Stanislav Korenko and Stano Pekár describe the effect of one wasp, Zatypota percontatoria, which hones in on the abdomen of a spider and injects its egg right in there. When the egg hatches the larva feeds on its host.

Initially, for the spider, it’s business as usual–the host keeps spinning webs to catch flies. But when the larva is reaching maturity, the zombie mind-control kicks in. The spider slave stops its normal web-spinning pattern and begins spinning a different kind of web–one that is an ideal dream home for a wasp cocoon, with a platform to keep it off the ground and a hood to shield it from the weather. For the wasp larva, the spider becomes architect and couturier in one. And when the specially commissioned web is ready, the larva bursts from the spider, killing it, and spins its own cocoon in the web.

Messing with a spider’s web-making is only the tip of the zombie-wasp iceberg. Take the small, pretty and utterly terrifying jewel wasp, for example. This parasite is only a few millimetres in size, yet it builds a nest for its eggs inside a living cockroach by zombifying the far bigger, stronger host. The process is queasily fascinating to watch. The jewel wasp carefully selects its victim. It cannot overpower the cockroach, so instead it uses neurotoxins and ‘mind control’, the like of which humans cannot match, and even the White Walkers would admire (well, maybe not. It’s hard to imagine them taking time out from their icy evil to watch a David Attenborough documentary).

The first sting the wasp administers to the cockroach makes the creature’s front legs buckle so it is unable to escape; the second sting is delivered with a remarkable precision to the exact area of the cockroach’s brain that seems to control its movement and (if we can speak of such a thing in relation to a cockroach) its free will. Scientists have actually developed a ‘vaccine’ that can ‘de-programme’ zombie roach if they can get to it at this point in the process, so there is some hope.

Now because the wasp is so tiny compared to the cumbersome cockroach, carrying her host is out of the question. Instead, the wasp bites down on the cockroach’s antennae in order to lead it to the exact spot she wants it to go, ‘like a dog on a leash’. (Some researchers have speculated this also enables the wasp to ‘taste’ how well her neurotoxins are taking effect in the cockroach’s blood; it has yet to be proven, but whatever she’s doing it’s far more sophisticated and precise than anything a human brain surgeon could master).

Just like the wights and the White Walkers, the cockroach can still move of its own accord, it’s just lost the will to unless its wasp mistress leads it. When they arrive together at the spot the wasp has decided on for her nursery, she digs a hole (the parasite wasp equivalent of painting the walls pink or blue) and then lays her egg on the underside of the cockroach, who also decides, hey, I like it here too, so it isn’t going anywhere… ever again. Again, just like the wights, whose severed limbs will still serve the will of the White Walkers until they are completely destroyed, every last part of the cockroach is used and subjugated to the higher purpose of the wasp’s young. The egg will hatch and the wasp larva will burrow headfirst into the cockroach’s uncomplaining body. Hungry, the picky young larva delicately eats some of the spare ‘stuff’ in its host’s thorax, thus ensuring the still zombified, unresisting creature is kept alive by leaving the cockroach’s vital organs until last. (It delicately munches its way round them, like pizza crusts.) Then, one day, when the wasp larva has grown big enough and strong enough from all that delicious living cockroach, it bursts out of the cockroach’s body, shakes its wings free and flies away. Finally, having served its purpose (as well as breakfast, lunch, and tea) the roach host dies.

Some parasites appear to possess utter ruthlessness alongside a wonderful sense of humour. A parasitic nematode infects ants and doesn’t mess with their minds much at all; it just gives them an enormous red arse. The affected ant gets spotted by a bird, who misses the joke somewhat and mistakes the ant’s junk-filled trunk for a delicious berry. A moving berry, with legs, that’s waddling along with a whole line of perfectly normal ants. Well, the bird is busy and if you’re a hungry bird you don’t look a gift berry in the… whatever. As it happens, when it comes to delicious berries, birds are always ready for this jelly. So, that’s how nematode eggs get inside a bird, the bird then defecates them out from a great height–thus spreading its nematode eggs far and wide to entrap more hapless booty-ants.

These manipulations seem to have parallels with the complex interactions in the World of Ice and Fire between The Children of the Forest, the While Walkers and the Wights. As we discover in Season 6 of Game of Thrones, the Children of the Forest originally created the White Walkers thousands of years ago as a means of fighting back against the ‘First Men’ who had invaded their homelands. The Children captured some of these men and changed them from regular human beings into White Walkers, by injecting them in a particular way with dragonglass. (This is a little reminiscent of our earlier encounter with the jewel wasp, who injects the cockroach and turns it into the protector of its young–both the tiny wasp and The Children are trying to safeguard their futures by harnessing a stronger force to do their bidding.) However The Children seem to have lost control of the White Walkers at some point, and the White Walkers in turn begin creating their own ‘zombie’ servants, the Wights, over whom they exert much stronger control…

I talked to Dr Kelly Weinersmith, Huxley Faculty Fellow researching how parasites manipulate host behaviour in the BioSciences Department at Rice University, Texas, to understand more about this cunning behaviour in our world. She explains the behaviour and ultimate ‘aims’ of different types of parasite–‘subtle manipulators’ versus ‘all-out zombifiers’.

‘Trophically transmitted parasites are parasites that need some or all of their hosts to be eaten by the next host in the life cycle in order to be transmitted. The nematode (who we met earlier) needs the ant’s abdomen to be eaten by birds. These parasites need their hosts to die in a very particular way, since dying any other way would mean death for both the host and parasite.’ Dr Weinersmith tells me that it’s possible that the parasites in these cases are ‘letting’ their hosts generally behave normally, ‘since natural selection has likely favoured hosts that behave in ways that tend to keep them alive. By altering just one or a few behaviours, the parasite may be able to increase the probability that the host survives until it has a chance to be eaten by just the right kind of predator.’

On the other hand–parasitoids are more likely to all-out zombify their victims. Like the White Walkers who ruthlessly control their zombie servants’, the Wights every movement, parasitoids leave nothing to chance. Dr Weinersmith quotes one of her colleagues, Professor Shelley Adamo, who calls them ‘evolution’s neurobiologists’ as they can do things human neuro-scientists can’t do (though in some cases this is definitely for the best). In a filmed talk for Smithsonian magazine, Dr Weinersmith gives a breathtaking example of the way a tiny fungus is able to control its ant-host, manoeuvring it to a precise height (25cm) on the North-North West side of a plant’s leaf, finding its way to a leaf vein at solar noon. ‘Wow!’ exclaims an audience member. ‘Yes–wow!’ says Dr Weinersmith. ‘If your mind isn’t blown by how specific that is we can’t be friends.’ But to return our earlier wasp and cockroach example, the wasp controls the cockroach’s behaviour so it can hide it away somewhere where the host won’t get eaten by predators. The parasitoid’s eggs then hatch in the cockroach and eat the insides of the cockroach. The parasitoid is going to kill the host outright at some point (e.g., by eating it alive). Dr Weinersmith speculates ‘maybe the important evolutionary difference here is that the parasitoid controls when the host dies, whereas the trophically transmitted parasites need to hang on until the right predator happens to come around.’

While this manipulative behaviour is fascinating by itself, it also has surprising potential benefits for possible future research into new types of drugs for humans. As we’ve seen, parasites are hugely adept at manipulating their hosts by affecting their brains. They are able, for instance, to exert an influence across the blood-brain barrier (that’s the membrane that exists as a protective measure against the passage of potentially harmful substances into the brain). A fish parasite that Dr Weinersmith studies appears to have a remarkably ‘calming’ effecting on its host–preventing it from stressing out at–well, the usual things that stress fish out. Could greater knowledge of how this ‘calming’ effect works one day lead to better anti-anxiety drugs for humans? Possibly! So it seems that, as Dr Weinersmith points out–rather than focusing on the evils of mind control and zombie horror stories, if we can learn from these highly skilled manipulators, one day they may lead us towards diminishing rather than increasing human suffering.

Secrets in the Ice

Secrets in the Ice

In our world, as in the Lands of Always Winter, North of Westeros the cold keeps all kinds of secrets. Scientists working in Antarctica are using finely balanced drills to bore as deep as three kilometres into glaciers and ice sheets, extracting rods of ice known as ice cores to catch a glimpse of undiscovered history. These ice cores have allowed us to look back as far as 800,000 years, and there is hope that it will one day be one million years or more.

When I speak to Dr Tamsin Edwards, lecturer in Environmental Sciences at the Open University, she’s just back from the British Antarctic Survey (BAS) labs. There’s a photo of her on Twitter beaming with utter delight as she holds a tiny off-cut ice chip to her ear. The Survey have a bag of leftover ice core chips and their visitors can rub them between their fingers and listen. When the ice is exposed to a bit of human heat the bubbles of ancient atmosphere trapped inside it audibly fizz out. Gases that were caught in ice when woolly mammoths, Ancient Greeks or ruffed Elizabethans roamed the Earth, are freed into the air again after their long, cold imprisonment. (‘It’s such beautiful ice too–perfectly clear, apart from lots of tiny, identical bubbles,’ Dr Edwards emphasises, with an ice connoisseur’s eye.)

Scientists can analyse the composition of trapped air bubbles in the ice core to give us a record of Earth’s climate history.

Glaciers contain layer upon layer of fallen impacted snow, and to a glaciologist the sizes of the snow layers are like the rings of a tree to a dendrochronologist. It is possible for them to tell us, for instance, how much snow fell in a particular year. And thanks to tiny amounts of gases, dust and particles of debris that get trapped when fluffy snow falls onto fluffy snow and freezes, they can tell us more about conditions at the time the ice formed.

Nearby vegetation contributed ancient pollen to the ice cores; climate scientists can even see which way the winds were blowing from this pollen and detect other distinct detritus that has gusted in from elsewhere in the world. Likewise, violent volcanic eruptions leave a layer of ashy dust and tiny shards of volcanic glass amid the ice crystals, telling tales of cataclysms before recorded human history began.

Dr Edwards shows me data she uses in teaching that measures dust with lead in it that blew onto ice sheets many years ago and remained frozen and trapped ever since. If, like me, you are not particularly fond of, or adept at, housework you may be used to uncovering extensive dust-based revelations about the past of your own environment–probably a few minutes before you’re expecting an important visitor to arrive. But the level of historical detail revealed by this ice core is extraordinary.

Climate scientists can identify the period when humans discovered cupellation (a process that metal-workers have been using from about 500 B.C. to extract gold or silver from base metals). We can see there’s a distinct rise in icy lead dust when the use of coinage became widespread, first in Ancient Greece and then across the Roman Empire, leading to a pre-Industrial Revolution peak–before a sudden fall when the Roman lead mines were exhausted, and the Roman Empire itself began to decline.

From those bubbles of gas trapped in Antarctic ice cores, scientists like Dr Edwards can analyse the levels of carbon dioxide (CO2)and other greenhouse gases in the atmosphere, way back into the past, and how those concentrations were created in the first place. It turns out that carbon atoms are rather good storytellers with a great memory for times and places. For instance, by measuring the ratios of different types (or isotopes) of hydrogen atoms, scientists can see the difference between CO2 that arrived from living things and CO2 that arrived from, say, burning fossil fuels once the Industrial Revolution really got going in the 19th century. Each slice of the ice core tells a story about the world it came from, its climate conditions, and how much ice existed on the planet at that moment.

Putting this information together, climate scientists came up with the famous saw-tooth shaped pattern of climate change which illustrates our Earth’s long history of ice and fire. Ice ages come along every 100,000 years or so, with greenhouse gases rising and falling in regular patterns. But accelerating technological change, and a growth in population and consumption mean CO2 emissions have rocketed in the past 100 years, causing potentially catastrophic consequences for the human race.

Inevitably, climate change plays a major role in Game of Thrones. As George RR Martin told Al Jazeera America in 2013, ‘climate change… [is] ultimately a threat to the entire world. But people are using it as a political football instead… You’d think everybody would get together. This is something that can wipe out possibly the human race. So I wanted to do an analogue not specifically to the modern-day thing but as a general thing with the structure of the book.’

In our world, politicians and rulers squabble and go to war, ignoring the more dangerous, all-consuming threat of melting polar ice caps. In the Seven Kingdoms, the different noble houses are too busy arguing amongst themselves to acknowledge the icy threat beyond the Wall, posed by the sinister White Walkers.

Back in the real world, climate scientists like Dr Edwards are eager to reach out to those on all sides of the global warming debate, to discuss the limitations on what we can know, the increasing complexity of models for prediction, and to assess the risks (and opportunities) of climate change. Whatever your views, it’s difficult not to be captivated by the beauty of the Antarctic ice cores–the waxing and waning of great empires recorded in ancient dust, water and gas found frozen in time deep inside an uninhabited continent at the ends of the Earth.