IN ITS EARLY days, the occupation of the Channel Islands bore little resemblance to what was happening in the rest of Nazi-occupied Europe. Life was comparatively safe and peaceful, and there was none of the systematic brutality which was terrorising communities on the Continent. This was not to last.

Between 1941 and 1944, about sixteen thousand foreign workers were brought to the islands to build their defences. Many of them were harshly treated, and islanders witnessed cruelty towards their fellow human beings on a scale the islands had never experienced. The islands, like the rest of occupied Europe, were drawn into the web of institutionalised viciousness which characterised every corner of Hitler’s empire.

The presence of thousands of emaciated foreign workers was painful evidence of Nazi brutality. It drove home the islanders’ awareness of their own vulnerability and the fact that their well-being depended on the fragile goodwill of the Germans. It also presented them with the most uncomfortable moral challenge of the Occupation: should they avert their eyes and thank God that the Nazis had other victims on which to vent their fury? Or should they do something to help these benighted workers?

At first the islanders did not know where these foreign workers had come from, or what they were doing among them. They were forbidden to talk to the worst-treated, from Eastern Europe, and gleaned only scraps of information from brief glimpses of the camps, or as they marched to and from their worksites. Those memories have haunted many islanders, and left them uneasy all their lives.

In the autumn of 1943 Maurice Green and his younger sister had gone out blackberry-picking near the vast German fortification works on Jersey, where tunnels were being excavated out of solid rock:

We were in an area where we weren’t supposed to be because there were a lot of Organisation Todt working on the tunnels there. I saw a German beating a French worker. He knocked him down and then kicked him and beat him with his rifle; I think he must have killed him. Then he sat down to have a smoke. He glanced up, and saw me and my sister. We were terrified. He shouted to us, ‘Come over here.’

He patted my sister; she was a little blonde girl and three years younger than me. Then he opened his haversack and took out his lunch and he broke his bread and cheese into three pieces, and gave me and my sister a piece each at a time when rations were very short. The worker was still lying there, behind him, with his head smashed open. He couldn’t have survived being beaten around the head with that rifle.

A Jersey policeman remembers passing one of the makeshift camps which housed the slave workers: ‘One of those Russian workers was hanging by his feet and he was still wriggling a bit. I made it my business to pass along the road the next day, and he was still hanging from that tree, but there was no movement in him. I didn’t mention it to anyone. I didn’t find it over-necessary to speak about it.’

Mike Le Cornu, a teenager, lived at L’Etacq, in the remote north-west corner of Jersey: ‘There was a quarry nearby. They used to bring slaves in lorries to unload huge machines for the quarry. Once one of these machines fell on a slave worker’s legs. They got two other slave workers to pick him up and throw him in the lorry and he was just left there all day. He must have died there. It was a very hot summer day. We could see this from our house.’ Every year, on the anniversary of the Liberation, Le Cornu returns to a particular field where there used to be a camp. For him it is a private moment of remembrance for the suffering he witnessed as a boy:

I’ve never forgotten the sound that came out of the huts there. I still get emotional. When people are starving, the pitch of their voices rises. The sound was like lots of birds in an aviary. As children, we used to go close to the camp fence and watch. Sometimes we pushed nuts and apples through the wire. The OT had big whips and would put yokes on the little children to fetch water. There was one Russian who stood out so clearly; he used to pat the children on the head as they went past. He must have been the only light of hope in that camp.

While I was watching, there was a Jersey farmer beside me and he saw this cruelty as well and he said [of the foreign workers], ‘They’re just savages from the mountains.’

A Jersey policeman recalls one particular Russian prisoner being brought into the police station. The police considered the Russians as something of a menace both to themselves and to the local population when, as he puts it, they were ‘running wild around the island’, and they regarded it as their duty to send them back to ‘where they belonged’. The policeman was deputed to return the prisoner to his camp. In a gesture of kindness, rather than march him up to the front entrance, he took him round to the back of the camp, where the Russian began to scramble under the rolls of barbed wire. Unfortunately he became trapped in the wire, and was soon spotted by a senior Organisation Todt officer. The officer rushed up and began savagely kicking the prisoner, who in his desperate efforts to escape became even more entangled. The kicking continued until the prisoner was motionless, presumably unconscious. By this time the OT officer had drawn his revolver. The policeman vividly remembers his feelings of powerlessness. There was nothing he could have achieved by attempting to intervene, and he remembers being very much aware that, if anything happened to him, his wife and two young children would be left unprovided for on the island. In the event, there was nothing he could do but walk away.

Some islanders distanced themselves from the tragedy they were witnessing. They belittled the suffering of these foreigners, dismissing them, like the Jersey farmer, as ‘savages’. They regarded these unwashed, unshaven creatures as scarcely human, and complained that they spread diseases. They were also exasperated by the foreigners’ continuous plundering of food stores, livestock and crops in the fields. Many farmers saw them as a nuisance, rather than recognising that their thieving was born of desperation. Some still say today that the wartime foreign workers were all criminals and homosexuals the Nazis had plucked from Soviet jails. A significant number of islanders, however, risked imprisonment – and in some cases even their lives – in order to show compassion and offer help to the prisoners (see Chapter 6).

The sad story of the foreign workers takes us deep into the organisation of the Third Reich’s war effort, where millions of people were transported from one end of Europe to the other to fulfil the Nazis’ need for labour. The experiences of the workers on the Channel Islands explodes the myth of the Model Occupation.

Adolf Hitler was immensely proud of his British conquest, and after the series of ineffectual British military raids on the Channel Islands in 1940–41, he became alarmed that they might be recaptured. On the eve of Operation Barbarossa – the invasion of the Soviet Union – in June 1941, Hitler was worried that his empire could be vulnerable to attacks on the Atlantic coast. He believed that battered British public opinion would demand some bold military achievement, and that nothing would suit that purpose better than a daring recapture of the British Crown’s possession.

Hitler became obsessed with ensuring that this tiny part of the Reich should not be lost. He argued that it had a strategic value, and was his ‘laboratory’ for Anglo-German relations. After the war was over, he postulated, and France was independent, the islands would remain German, a valuable U-boat base for the western Channel and a perfect place for good Nazi families to holiday in a ‘Strength Through Joy’ camp.

In the midst of feverish planning for the biggest invasion ever launched in human history, Hitler found time to study the defence plans for the Channel Islands. He was not satisfied, and ordered a host of new measures. The Organisation Todt was to provide the labour. Hitler demanded twice-weekly progress reports and the drawing-up of long-term fortification plans. He was determined that the islands’ defences should be impregnable, and should be built to last into the next millennium.

Over the following eighteen months the islands became a vast building site, as a crash building programme was implemented to fulfil Hitler’s ambitions. The sleepy holiday islands were transformed into the most strongly defended possession of the Reich. Hitler’s alarmed commanders whispered about the Führer’s ‘Inselwahn’ – island madness – and worried that the resources devoted to the Channel Islands would weaken defences on the much more important northern French coast.

More than 484,000 cubic metres of reinforced concrete were poured into the Channel Islands, and 244,000 cubic metres of rock were excavated. Anti-tank walls three metres high and two metres thick were built along the beaches. Gun emplacements were constructed on the cliffs and headlands. The biggest gun, the Mirus battery on Guernsey, took eighteen months to build and had a range of fifty kilometres; 45,000 cubic metres of concrete were needed to build its base. An adjacent underground barracks was excavated, with the capacity to house four hundred men.

Roads had to be built or widened to transport materials to building sites, and on Jersey, Guernsey and Alderney, railways were specially constructed. Mines were laid along all the islands’ coasts. In June 1942, eighteen thousand mines had been laid, which was judged sufficient by the German experts. By April 1944, this figure had swollen to a fantastic 114,000 on all the islands, and the final figure for Jersey alone was sixty-seven thousand.

According to German records, at the peak of the construction work in May 1943 the OT had brought sixteen thousand foreign labourers to the Channel Islands; 6700 on Guernsey, 5300 on Jersey and 4000 on Alderney. This was a tiny part of the vast labour army of occupied Europe – by 1944 it had swollen to 1,360,000 people – which the OT was using to build roads, bridges, fortifications and factories to support the Nazi war machine.

The workers on the Channel Islands had come into the OT by four routes.

Firstly, the OT contracted out work to private companies. Dutch, French, German and Belgian building firms and civil construction companies worked on the islands’ fortifications, and recruited their own workforce. Channel Island companies also worked under contract to the OT. These foreign workers, who made up about ten per cent of the total, were usually skilled and relatively well-treated; they received pay, adequate food and holidays.

Secondly, when there were insufficient volunteers, compulsion was used, and forced labourers supplemented the workforce. Labour quotas were imposed in countries such as Holland and France. Eighteen-year-old Dutchman Gilbert van Grieken officially ‘volunteered’ to join the OT to work on Guernsey. In reality, he was told he would have no ration cards if he refused to comply with his local employment office’s instructions. He worked as a builder on Guernsey; he was paid, and was free in the evenings to come and go as he wished. Skilled OT workmen like van Grieken, from ‘Germanic’ nations like Belgium and Holland, lived in requisitioned private houses in St Peter Port and St Helier, or in camps closer to their place of work. They may have got a few kicks up the backside and some verbal abuse, but they lived to return home after the war. Between twenty and twenty-five per cent of the islands’ OT workforce could be included in this category.

Thirdly, the bulk of the OT workers on the islands, about forty per cent, came from the occupied territories of the Eastern front, where they had been rounded up behind German lines. They included prisoners of war, and boys too young and men too old to have been conscripted. They were mostly from Russia, Ukraine and Poland. According to Nazi racial theories, Slavs were ‘Untermenschen’ – sub-human – and were consequently used as slave labour; they were not paid, and had little freedom or time off. They were seldom deliberately killed, but the inadequate food, arbitrary beatings, utter disregard for their safety at worksites and lack of medical care exacted a heavy price in lives.

The remaining quarter of the workforce was something of a ragbag of different nationalities. Each had their own story. Several thousand Spanish Republicans arrived in the islands; they had fled to France after Franco’s victory in 1939, and were handed over to the Germans to help fill France’s labour quotas. Similarly, the French rounded up North African dockworkers from Algeria and Morocco and a few Chinese in ports such as Marseilles. French Jews also appeared on Alderney, as did a thousand-strong SS building brigade which included German, Czech, Dutch and French political prisoners.

The concrete bunkers are now overgrown with brambles, and the anti-tank barriers serve as seawalls. It is hard to imagine the suffering their construction entailed now, especially on a sunny summer’s day, when families picnic on their concrete bulk and the beaches are dotted with the brightly coloured towels of holidaymakers. Even the dank, dark tunnels of Guernsey, Jersey and Alderney, used for fuel and ammunition depots and underground hospitals, have almost lost their power to disturb. Having survived the depredations of generations of inquisitive children and memorabilia hunters, several have been converted into highly successful museums, bustling with coachloads of tourists snapping up souvenirs and scones.

A few scraps of graffiti, such as a star of David, or initials scraped into the setting concrete, hint at the hundreds of men and boys who lost their lives building these vast monuments to Hitler’s grandiose ambitions. For the last fifty years, most of the individual workers have remained nameless and faceless. Little was known about where they had come from, how many of them were brought to the islands, the conditions of their lives there, how many died or what happened to those who survived the war.

There were survivors living in London, Paris, Belgium and Cologne, but few people were sufficiently interested to listen to their stories. Hundreds more disappeared behind the Iron Curtain in 1945, and returned to their homes in Russia, Ukraine and Poland. Most have now died, but since the collapse of the Soviet Union, sixty-four of the last Channel Islands survivors have been traced there. Many of those I met were astonished that anyone was interested in the memories they had buried in their hearts for half a century, and which some of them were telling for the first time. It has finally become possible to put names and faces to these victims of the Channel Islands’ war.

Vasilly Marempolsky was fifteen when he arrived on Jersey in August 1942:

My sister had been selected to go and work for the Germans in Germany, but she ran away, so the Germans took me. I was put in a cattle truck and travelled through Poland and Czechoslovakia to Germany, and then on to Paris and finally St Malo. We were beaten with sticks as we were loaded onto the ships; it was the first time I had seen the sea.

After we landed on Jersey, I was taken to Lager Himmelman on the west coast near St Ouen’s. The camp consisted of only six huts and was surrounded by two rows of barbed wire. In the huts there were three wooden platforms, one on top of the other, which served as beds; there was a bit of straw on them, but no blankets. There were about five to six hundred people in the camp, and we were organised into working units of fifty men. We nicknamed the guard who was in charge of our unit ‘Cherni’ – ‘the Black’ – because he had black hair.

We got up at five o’clock and had dirty black water called coffee. After breakfast, we heard the whistle and we had to stand to attention for the Germans; those who were slow were beaten.

We were building a railway and we had to level the ground. Sometimes we had to crush rocks. Between one and two o’clock we had a lunch break and we were given turnip ‘soup’; it was water with a tiny lump of turnip in it. We usually worked for twelve or fourteen hours a day. The Germans watched us from behind, and as soon as anyone paused to straighten their back, they would beat him. We had to stay bent over and pretend to work all the time. Then the Germans got wise to that and watched to see if we were working hard enough. If they decided we weren’t, the Germans would beat us.

At the end of the day, we all received tiny cards with ‘supper’ printed on them. This entitled us to half a litre of soup and 200 grams of ‘bread’ which had bits of wood in it. Every second Sunday we had a day off and then we didn’t get any food because we weren’t working.

Sometimes as we marched back to camp, we would steal a turnip or a beetroot. Sometimes an islander would put out some bread or proper soup for us. I never knew the islanders’ names but we knew they had a lot of sympathy for us. Within a few months of arriving, my jacket had disintegrated. As we marched past a farm I saw some people waiting by a gate. One of them was an island girl and she had a big jacket and she threw it over my shoulders. It was very useful.

Lice were a great problem because there was no disinfectant. People began to catch illnesses like typhus and dysentery and many people died of exhaustion. By the end of October I couldn’t walk, I was so weak from exhaustion and dysentery, but my friends helped me. One day I had stayed behind when the others went to work and I went to the camp medicine post. A Spanish doctor and nurse at this post took me to a hospital the Spanish had set up for the foreign workers. A Spaniard took pity on me and nursed me back to life; his name was Gasulla Sole. A Jerseywoman also came to the hospital to give me bread.

When I was better I had to go back to Lager Himmelman. The men had begun work on the underground hospital.fn1 We thought it might be some kind of mine but it had no coal. We had to march from the camp to the underground hospital every day. About a quarter of our brigade died, and they were replenished by men from another camp on Jersey.

It was barely light when we began the march to the underground hospital. We were very young boys, we were thin, exhausted, dressed in torn clothes and blue with cold. The worksite was a huge labyrinth of tunnels. I was terrified. The roof was supported by wooden props in some places and we could hear running water and smell damp. It felt like a grave. The walls were rough-hewn and there was mud underfoot. Everywhere there were people working like ants. It was hard to believe all these tunnels had been dug out by the weakening hands and legs of these slaves. People were so frail, they could barely lift a spade. The future for everyone was the same – death.

During the night shifts, they blew up the rock with dynamite and slaves had to crush the stones into small pieces and then load the trucks with the debris which was taken out and emptied. We were making a tunnel through virgin rock and thousands of tons of rock were excavated. For twelve hours a day we were underground. Many people died, especially during the dynamite explosions, when they were wounded by falling pieces of rock. Those who were seriously wounded were taken out by SS guardsfn2 and were never seen again. I remember one morning three prisoners had been killed in the next-door tunnel where there had been a rockfall. A week later eighteen people were killed when some wooden props collapsed and the roof fell in.

I think about five hundred Russians and Ukrainians died on Jersey. The same lorry which brought the soup took the corpses away from the worksite. ‘Cherni’ killed more than one person by beating them with a wooden stick or a rubber hose filled with sand.

Most of the prisoners on Jersey were either Spanish or Russian. Some of the Spanish were doctors, and they helped the Russians because they remembered how the Soviet Union had helped them in the Spanish Civil War.

Vasilly Marempolsky is now a Professor of Ukrainian Literature in the industrial city of Zaporozhye in eastern Ukraine. He was fortunate enough to be able to resume his studies after the war, and was chosen to visit Jersey as part of Soviet delegations in 1975 and 1985, to mark the thirtieth and fortieth anniversaries of the Liberation.

Gasulla Sole, the Spaniard who saved Marempolsky’s life, stayed on Jersey after the war and married a local girl. Before he died in 1980, he told his life story to the Imperial War Museum’s sound archivist:

I was born in 1919 in Barcelona into a Republican family. When the Civil War ended in Spain, I escaped to France where I was put into one camp after another; the conditions were terrible. When the war was declared the Spaniards were forced to work for the French and I worked on the Maginot Line. After the French had been defeated, the Germans asked for volunteers to work for them. About a thousand Spanish were swapped by the French government for French prisoners of war captured by the Germans. We had no choice about it; all we could think was that every day we were alive was a bonus.

I worked on the submarine base in La Rochelle before I was sent with another three hundred men to Jersey. We had to build a camp at St John’s [a village in the north of the island]. Jersey was painful, but it was not like Belsen; we were lucky. I worked as a nurse in the Spanish hospital. Twice, patients we couldn’t cure were taken off Jersey in Belgian boats which had been used for transporting cement.

Rations consisted of a tiny piece of what was called cheese, a few carrots and vegetables and some bread. There was no meat. People ate worms, there was so little food. We did some petty sabotage such as derailing trains and breaking cement mixers.

As Marempolsky and Sole’s accounts indicate, there were small ways in which islanders on Jersey helped the foreign workers to survive. The jacket flung around Marempolsky’s shoulders and the bread brought to him in the hospital may have saved his life. Many slave workers also managed to steal the odd bit of food from the farms and villages. The Spaniards set up a hospital in one of the camps, in which they treated the slave workers with the help of islanders concerned at the danger of infectious diseases spreading.

On Alderney, these forms of help were not available. The few Britons living or working on the remote island were vastly outnumbered by the thousands brought to it to build fortifications. This was one of the factors which made Alderney a hell on earth for the workers who lived and died there between 1942 and 1944.

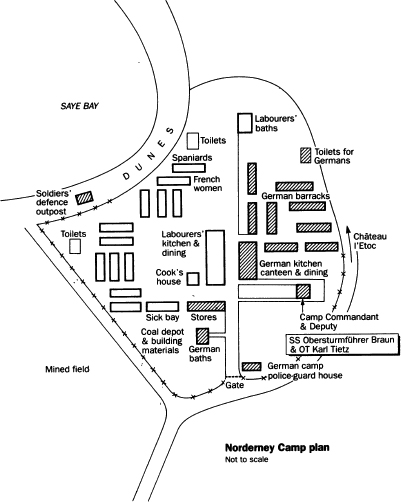

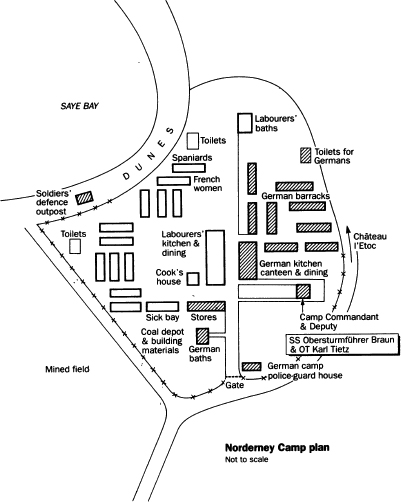

There were four camps on Alderney, each named after a German island in the North Sea: Borkum was largely for skilled (and paid) ‘Germanic’ workers from Belgium, Holland and Germany. Helgoland, Norderney and Sylt were for the slave workers. The last two were the worst.

It was not the OT’s job to run death camps, but the combination of their haste to achieve construction targets on Alderney, the corruption which flourished on this outpost of the Reich, and their disregard for the safety of the slave workers ensured a terrible cost in human life. There is evidence that the higher reaches of the OT attempted to check the loss of life and instituted inquiries on the island, and complaints were allegedly made by the military authorities on Alderney. But Alderney was too distant for the writ of German rule to run effectively; black marketeering was rampant, and only a fraction of the rations calculated as necessary in Berlin reached the bowls of the Alderney workers. The German authorities on Guernsey and Jersey heard disturbing rumours of what was happening on the island, and islanders returned to Jersey and Guernsey after their stints working on Alderney shocked by what they had seen. The island was referred to in hushed voices – a horrible and embarrassing secret.

About twenty Alderney survivors live near the city of Orel, four hundred miles south of Moscow. They form the remnants of a contingent collected from villages in the district in June 1942, when it was deep behind German lines.

The region around Orel is a land of undulating fields which stretch to the horizon under vast skies. The scale is continental; forests cover huge patches of the map. The roads are wide and the verges even wider. Space is abundant, and the land provides no obstacles such as mountains, ravines or even boulders.

A few of the run-down wooden houses where the Alderney slave workers would have been born remain, shabbily painted in bright colours and with carved shutters. The gardens are carefully tended, the orchards full of twisted old apple trees and surrounded by rickety wooden fences. The winters here are harsh, but they give way to sweet summers when the gardens are full of the much-loved dill and coriander, and the forest floor is carpeted with rich, fleshy mushrooms.

The landscape of the tiny island of Alderney must have been as alien as the moon to the slave workers from this country. They had never seen the sea, and had little conception of what an island was. On Alderney the great body of water, the Atlantic, is visible from every point, pressing in, pounding at the cliffs and rolling over the sandy beaches. Alderney is tiny; there are few fields and virtually no trees behind which to shelter from the gales which sculpt the bushes and hedges.

The Russians remember being terrified of the sea and its strange sounds. They hated the island’s wetness, its frequent rain and mists heavy with water. They were stunned to see houses made of stone with little walled gardens, and the narrow, paved streets of St Anne’s, Alderney’s small town. Perhaps it is because this environment was so strange and unfamiliar that Alderney has remained stamped on the memories of the survivors with an extraordinary clarity and detail.

Georgi Kondakov, one of the survivors of Alderney, has doggedly traced sixty-three other survivors over the last ten years. He lives in Orel in a tiny two-bedroom flat, bulging with family and books. He had puzzled over his recollections of that strange, wet island for twenty-five years before he managed to find out where Alderney was; a British businessman at a trade fair was finally able to tell him. At first, the other survivors Kondakov contacted were suspicious of him, and feared he might have links with the KGB, but they were won over by his remarkable charisma, his wide smile, handsome face and self-evident integrity.

Kondakov tells his story with slow deliberation, as if it requires a great effort to put words around these memories. At one point, his voice grew husky and his eyes were wet.

I was eighteen, and was working in a shell factory when the Germans arrived in Orel in October 1941. All the munitions factories were being blown up to comply with Stalin’s orders of ‘scorched earth’.fn3 They didn’t usually bother to tell the workers when they were going to blow them up. Besides, the factories were guarded, so there was no way out. Many were killed in this way. It was chaos, with the NKVDfn4 ordering one thing, and others ordering the opposite. I escaped from the factory and saw the German tanks in Orel. There were women screaming in the streets and fires burning everywhere.

I ran back home to my village and stayed there until 20 June 1942. The crops hadn’t been harvested because the men were at the front, so food was very short. We collected grain left over from the silos which had been burnt by the Russians to prevent them falling into German hands. The grain had been doused in petrol and we had stomach-aches after eating it. We even dug the snow to find left-over potatoes. That winter of 1941–42 was little different from life in Alderney, and I think surviving these conditions helped me to survive later.

The Germans imposed labour quotas on each village, and the skood [the village assembly] had decided that the fairest way to fill the quota was to take children from the largest families. I was selected to go and work for the Germans. My family were very shocked, my grandfather burst into tears and my mother fell ill.

We were loaded onto trains by the Germans. When the doors were first closed in the cargo trucks, people kept silent, and some were crying. Then the pain calmed down and we began talking to our neighbours. There I met the boy who was to become my friend, Kirill Nevrov. We mostly talked about one subject: where were we going, and what did the future hold for us?

We arrived at a huge sorting centre at Wuppertal in Germany. They decided where you should go according to your appearance. The older and weaker were led outside, and we never saw them again. Men were separated from women. People had to declare their professions, and they were led off in different directions. The young and healthy were designated for hard labour in the mines or on construction projects. I saw a hut full of people who had come back from the mines in Belgium. They were so exhausted they looked like walking skeletons, and they cried out for food. I was completely overwhelmed.

Kondakov was sent to St Malo, where he was loaded onto a ship to be taken to Alderney. The boat journey took several days, and the German guards poured water into the packed hold for the thirsty prisoners, who had to open their mouths and cup their hands as best they could to catch the precious drops. On arriving at Alderney, the slave workers were divided between Helgoland, Sylt and Norderney camps. Kondakov was sent to Helgoland.

About four hundred people died in Helgoland while I was there; many died at the beginning of January 1943, when it was cold. One of the most common signs of the approach of death was that people started to swell. When we were woken in the morning, there were corpses in the beds beside us. Those who had been allowed off work because they were sick had the job of collecting the bodies, which were then thrown from the breakwater into the harbour. When I was building a road in the harbour, I saw special lorries come to the breakwater and tip bodies into the sea two or three times. Each lorry contained at least eight corpses. Human psychology is a strange thing; one gets used to even the most terrible experiences. Nature created human beings to adapt quickly to any situation.

All our conversations on Alderney were about food or the death of someone we knew. On our one day off a month we discussed home and the progress of the war. If my brain was not too exhausted I would always dream of home.

At first I had the trousers which I had been wearing when I was taken from home, but the fabric disintegrated. I found a blanket and cut holes in it for my arms and head. For a belt I used some wire. The blanket covered my knees like a poncho and I attached sleeves to it with wire; the sleeves were different colours initially, but they both became cement-coloured. I wrapped my feet in cement bags and wore sabots, but my legs were open to the wind. I suffered from the cold and wet. I had blisters and boils on my hands which eventually got infected.

Many times when I was on Alderney I thought death was close. Most of my worst memories come to me now as nightmares; in the daytime I can suppress those thoughts in my subconscious, but against the nightmares I am powerless. One nightmare I had on Alderney came to me at the end of October 1942. I was completely exhausted at that time, my hands and legs had started to swell and I thought I was dying. I dreamt we were building a road, and we dug a hole and suddenly a staircase opened up, going down to a huge long hall with a vaulted ceiling. Sitting at long tables eating were rows of naked people. I was also naked and very hungry, but there was no room at the table, so I slipped under the table and gathered breadcrumbs. One of the people sitting at the table kicked me and told me to go and bow to Death. I was frightened, but they motioned to me that she was next door. I followed their instructions and was greeted by a skeleton in a red robe. When I fell on my knees and kissed her feet, the skeleton said to me, ‘Go back, go back.’ I woke up, and found myself lying on my bunk. My heart did not seem to be beating and I was covered with sweat; I didn’t know whether I was dead or alive. I still don’t know whether it was a dream or whether I nearly died, but death had not wanted me, and after that dream my life improved.

We had a guard who let us go off to steal food. I often stole food at night. The Germans started shooting prisoners who were stealing potatoes out of the fields, but the desire for food was much stronger than the fear of death. The will to live is instinctive in each living creature. We were also determined to defy the will of the Germans, who had told us that no one would leave the island alive.

The prisoners worked in pairs; one would steal and one would protect him from being robbed by other prisoners. The Russians never stole anyone’s bread ration, that was sacred because someone’s survival was at stake, but anything they might have managed to steal could be taken; it was an unwritten law.

I was imprisoned and beaten for stealing food three times. Once I was selected to go to Sylt camp,fn5 but I escaped by hiding in a sewage ditch. I almost died there because my arms and legs went numb with cold and I couldn’t move them.

But Kondakov survived, and in October 1943 he was taken to northern France to work on construction projects; the work was easier and food more plentiful, and his health improved.

The friendship between Kondakov and Kirill Nevrov, who met on the train journey from Orel to St Malo, has lasted fifty years. It has been punctuated by astonishing coincidences, which both delight in recounting.

On arriving at Alderney, to their bitter disappointment, they were separated, and Nevrov was sent to Norderney camp. It was not until two years later that they bumped into each other in Paris, during the jubilant celebrations following the city’s liberation in August 1944. They travelled home to Orel together in 1945, and then lost contact for several years, until by pure chance they were allocated flats almost next door to each other and Kondakov was offered a job at the plant where Nevrov worked.

Nevrov has an air of faded refinement, which he attributes to the year he spent in hiding with Russian émigrés in occupied Paris. He made a point of using his rusty old-fashioned French as he kissed my hand and offered hospitality with the ceremony appropriate to Paris in the 1940s.

Nevrov was seventeen, and living in a village about twenty-five kilometres from Orel when the Germans invaded. His family had been relatively well off, and his father was the accountant with the local collective farm.

Our homes were taken for the German soldiers and we were forced out into hastily constructed shelters for the harsh winter. When spring came, the Germans started to round up young people, and I was unlucky. My father was very sorry for me, but there was nothing he could do.

We were transported in cargo trucks; they packed us in so tightly it was as if we were cattle. But even cattle are treated better. There were only tiny windows for fresh air and we were given food only twice on a journey which lasted several days. [People had to urinate and defecate in the trucks.]

In St Malo, I was very frightened by the sea. When we got onto the ship I felt we were floating in the air and the horizon was just a line of water. I was so relieved to see Alderney because it was land in the middle of this ocean, and I wanted to get off the water, which seemed like hell. I did not know that the island would turn into a hell. I still remember the sound of the sea roaring all day and all night.

We worked sometimes for as long as sixteen hours a day, building concrete walls around the island. Often we worked for twenty-four hours at a stretch, and we were then given half a day’s rest before resuming work. My only wish was to rest; it was completely exhausting. I didn’t even have the strength to move my hand. On one occasion we were working with the huge concrete-mixing machines and one man was so exhausted he lost his balance and slipped into the concrete. We told the German supervisor that someone had fallen in, but he said it was too complicated to stop the machine. It carried on pouring concrete over him. Many people died at the construction sites.

After two or three months people started to die at the rate of about twelve men a day. There was a yard in the centre of the camp where people were shot for stealing cigarettes. In the morning many people were found dead in their beds, and the naked corpses were loaded into trucks. A truck would tip the corpses at low tide into pits dug in the beach fifty to a hundred metres off the shore. There would be about twelve people in each pit. You could never find the grave after the tide had been in and out because sand had been washed over it. I saw the bodies being buried with my own eyes, because I was working about fifty metres away on a concrete wall.

Kondakov and I have discussed many times why the corpses were naked. Perhaps it was because people came from work in clothes which were soaking wet, and they would take them off to sleep naked and then die in the night. We also took off our clothes to get some relief from the parasites at night. People stole blankets, but they wouldn’t have bothered to steal clothes, because they were no more than rags.

I was nothing but skin and bones, and I had only the clothes I was wearing when they rounded me up in Russia the previous summer, which quickly fell apart. We made replacements out of old cement sacks; we cut off the corners to make holes for the arms and I used a rope as a belt. We used cement sacks for everything: blankets, leggings and even hats. We slept in cement powder because it was softer than our beds. We were covered in cement day and night and our hair got cemented. There was nowhere to wash it off, but it did give us some protection against parasites. My trousers went so stiff with cement that when I took them off they remained standing. I used to be able to jump from my bunk into my standing trousers.

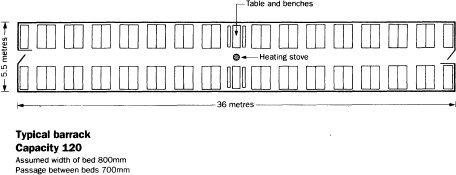

Our huts were about thirty metres long, with men sleeping on either side on two levels of planks. At first it was one blanket per person, but after people began to die they gave us more blankets. When you lay down you fell asleep immediately; there was no time to feel cold. It was the sleep of a dead man.

There was a passageway about one and half metres wide down the middle. At either end there were doors. There was a rail along the ceiling which the guards would beat with a hammer to wake everyone up. The last to leave the hut was beaten by the guards. We went to the canteen for breakfast, which was only a cup of herb tea that tasted of copper. There was about thirty minutes for lunch, which was cabbage soup; it only took a few minutes to drink it. Supper was more soup and bread. There was a one-kilogram loaf to share between seven people.fn6 The flour had been mixed with bonemeal and sawdust, so it wasn’t like proper bread, and it was as hard as a brick. Occasionally we got 10–15 grams of margarine. Going to the toilet during work was a farce; a German guard would hold out the spade for me to do it on.

One of my happiest memories was when a German supervisor with a pair of binoculars was standing near to where we were working. He was looking in the direction of England. You can’t imagine how strong my desire was to see England through those binoculars. The German saw me looking at him with shining eyes, so he offered me the binoculars and showed me how to adjust the focus. I was very happy to see England – it was as if the Holy Spirit had come down upon me!fn7

The worst times were when the weather was bad and the sea was roaring. Then I could have committed suicide. Alderney left a mark on the lives of all of us. Each time I go to bed or have a spare minute, I remember the things that happened on Alderney. I want people to know what it was like and to remember what happened. It was my sacred duty to come and talk to you.

I thank Our Lord for my survival, I never thought I would live to sixty-eight – not that I believe in God. None of us old people who have suffered so much in our lives believes in God. How can a superhuman being like God allow atrocities to happen to innocent people?

Ivan Kalganov, Alexei Ikonnikov, Alexei Rodine, Ivan Sholomitsky and Ivan Dolgov have less detailed memories. Their rough faces are worn by hard work and vodka. Talking of Alderney broke these tough men, and they tried to brush away the tears which spilled over their gnarled hands.

Kalganov is a simple man with a sheepish, boyish smile. He was so nervous about talking of his experiences on Alderney to a British journalist that his plump, red-cheeked, grown-up son Vladimir had accompanied him. Vladimir listened closely; it was the first time he had heard his father’s story.

Kalganov was working at the same munitions factory in Orel as Georgi Kondakov in 1941 when the Germans arrived, and he too fled to his village.

No one in our village had been able to evacuate east because we had been encircled by the German advance. We were trapped behind their lines. Everyone knew what occupation would mean, and we were all talking about atrocities before the Germans even arrived. It was a terrifying feeling, waiting for them to come. It took them a few months to reach us because the road from Orel was very bad. I remember the Germans arriving in my village. They had machine guns and they shot all the birds; they just sprayed bullets at the geese, chickens and hens. Whatever moved, they shot. Then they demanded sheep and all the cattle. They killed some with their machine guns to feed themselves. They only stayed a week at our village before moving on.

In the spring, the Germans divided the kolkhoz [collective farm] land up and distributed it amongst individual farmers. My father was a Communist, so my family got no land, although I had seven brothers and sisters. The only job I could get was tending other people’s cows.

In the summer of 1942 I was selected to work for the Germans. It was a complete surprise. A Russian policeman and a German came to where I was looking after the cows and told me. I was allowed home to say goodbye to my family, and I remember vividly my three-year-old brother running after me, waving goodbye. They put me in a cart along with about fifteen others from my village and took us to the railway station.

I saw the sea for the first time in St Malo, and I liked it; it was night and the water was calm, and the stars were reflected in the water. It was very beautiful.

Alderney was covered with barbed wire and signs saying ‘Beware of the mines’. I was sent to Sylt camp where I stayed until March 1943, when the SS arrived and I was moved to Helgoland. Sylt was terrible, terrible. If they caught you at the rubbish heap, you would be beaten. Dogs were used against us in Sylt.

Kalganov stumbled to a halt. He was crying. He insisted he would go on, but asked for a few moments to collect himself. Georgi Kondakov provided a glass of vodka, and Vladimir took him aside. Then he continued:

Sylt was much worse than Helgoland, because it was in a very exposed position on top of the hill and open to the winds. How many died each day varied. Sometimes it was six, sometimes a dozen. People died of dysentery, hunger or bad food. More Ukrainians and Poles than Russians died because the Russians were used to living in bad conditions. There were about five hundred men in Sylt camp, and at least three hundred died while I was there. I don’t know how I survived. I had boils, I was always wet from the rain and I was exhausted from the work. I nearly died on the ship back to France, but my friends helped me.

I hardly remember those friends now. If I had something to eat I shared it with them, and they with me; that was all our friendship consisted of. If we had any spare time we were too tired to talk, we just fell asleep.

We were marching from the camp to work once and I saw a man who couldn’t walk any longer. He was shot down right there by the Germans. I saw one man crucified for stealing; he was hung by his hands in the hut where the corpses were piled up. I think he was still alive when I saw him.

When I got up in the morning I saw dead bodies in the neighbouring bunks. Sometimes I saw that their lips, nose and ears had been eaten by rats. Rats ran over our bodies while we were sleeping, looking for the dead. There was a special hut in Sylt where the dead corpses were piled in the morning. Later they were taken away, and I saw corpses being loaded onto trucks. Other prisoners told me that they were dumped in the sea.

The food was just water with a few bits of turnip floating in it. Life was a constant struggle to find food. I found a good rubbish heap near to the construction site where I worked. It must have been near where German officers lived because there were different kinds of vegetable peelings and even cabbage leaves. I would fill a bag I had with this rubbish. Once someone from the kitchen saw me and set a dog on me. The dog tore all my clothing; I was very weak at the time. Again and again the dog attacked me. When the dog let go and I got back to work I was beaten with a stick by a German.

I didn’t know how many hours we worked or slept. Everything was a blur. All I know is that we went to bed when it got dark. I was working on the Westbatterie, the largest gun emplacement on Alderney, and sometimes we worked all night, especially when we were concreting the base of the guns.

I didn’t wash myself once the whole time I was there. My clothes were those I had brought from home, and they were crawling with lice. I could have scooped a handful of lice out from under my armpit. When we came back to the hut after work, we would shake out our clothes over a stove to burn the lice.

I still suffer from the memories; sometimes I can’t get rid of the thoughts. When I go to bed, it all comes back to my mind, and in my dreams I revisit all those places.

Ikonnikov’s face is raddled by drink. As he talks of Alderney, his eyes are wild:

On Alderney, people were treated like cattle; there was no hope of surviving. I was called number 146, no one ever used my name. A Dutchman in the Strabag Firmfn8 used to say that after the roads had been built on the island, we would be killed. We would either be destroyed or worked to death. People who stayed in the hut because they were sick wouldn’t be there in the evening. A man was killed for stealing bread in our camp. We came back from work, had supper and immediately fell asleep, and we never considered the question of how many people had died, or how they had died, or where they were buried. When a man is exhausted, he doesn’t talk.

I wouldn’t have survived if another prisoner hadn’t pointed out that the Germans kept pigs and grew potatoes in a place near the camp. He kept watch while I crawled under the fence to get potatoes. When one of the prisoners found something to steal, he shared it with the others. Once we broke the lock on the kitchen door and put all the rubbish in bags to take back to the camp. Two of my friends were caught by German guards and I hid amongst the pigs, but one of my legs was sticking out and they found me. We were put in a lorry, and we heard the Germans discussing what to do with us: the younger one said they should shoot us, but the older one disagreed, and said that we were dying of hunger and that when he had been a prisoner of war of the Russians in the First World War he hadn’t been shot. So we were sentenced to twenty-five blows with a stick. We were lucky – the commandant was a Polish German, and only the first few blows were on my body, then he ordered me to continue screaming while he beat the wall.

Once I found some cow leather which we boiled and ate. People were so desperate for food they went down to the beaches to get seafood. We gathered oysters, mussels and fish. But you had to be careful. Half a dozen people, maybe more, were blown up by mines on the shore. The area around the bakery was also mined. Some Russians tried to get bread by squeezing through the bars of the window. One of them was blown up and the German commandant ordered that a special coffin be made, and asked to see the corpse of a man brave enough to risk death for bread.

Not all the Germans were bad; some shared their food with us and some secretly helped us, but I don’t think the SS should ever be pardoned. To make Germany a human nation will take another fifty years. Some of the SS prisoners cried out to us that they had been in concentration camps since 1933, and told us we were only beginners compared with them.

I often think about Alderney, and I still have nightmares. Once I dreamt I was being eaten by a German, and I was so desperate to escape that I put out my arms as wings to fly, and then I saw the sea beneath me and found I was too weak to fly; I was terrified of falling into the sea.

One Sunday after the battle of Stalingradfn9 we were allowed to bathe in the sea; I was frightened of it at first, but I came to like it. It was transparent and I could see the fish. The island was very beautiful when the weather was fine. I liked the air – it was very soft and salty and had a strong smell of grass. I liked the stone houses around the harbour and the little gardens they each had. I liked seeing the other islands in the distance. I always had this idea that Alderney was a place where people before the war were happy and free, and when the war was over, they would be so again. We dreamt about escaping to England, but it was impossible to swim there.

Like Vasilly Marempolsky, Albert Pothugine lives in Zaporozhye in the eastern Ukraine, a huge steel- and iron-making centre where a forest of metal chimneys blaze brilliant flames and endlessly puff thick smoke into a polluted sky. Pothugine worked in these plants until he retired on invalidity benefit. The combination of his time on Alderney, a lifetime of smoking and Zaporozhye’s pollution has left his health in a parlous state.

Pothugine told his story with a fierce intensity; at times he staggered to his feet and flung his arms about in wild gesticulations, and at the points of greatest horror he fixed me with a penetrating glare. His diminutive wife Anna watched anxiously, for fear that the emotion the memories aroused would give him a heart attack.

Albert was born in 1928 in Belorussia, and when he was only four his father was killed in a peasant uprising against collectivisation. When the Germans invaded in 1941, his mother was drafted to dig anti-tank ditches around Bryansk, about a hundred miles from Orel, and was forced to leave twelve-year-old Albert and his ten-year-old brother to fend for themselves. They survived by collecting wild berries and exchanging them for milk. Their mother eventually returned, and in occupied Belorussia the family scraped a living for a few months, trading old clothes in remote villages for food to bring back to the town. On returning from one of these long journeys by foot, Albert found his home had been bombed and his mother murdered. He believes the culprits were ‘partisans’ – who, he claimed, were no more than bandits. He and his brother were forced to forage for food in the ruins of bombed buildings until the Russian police arrested them and handed them over to the Germans as ‘partisans’. They were separated, and it was not until 1953, eleven years later, that the brothers saw each other again.

Albert ended up in a forced labour transport which took him across Europe to Alderney; he was fourteen years old when he arrived in Helgoland camp. He never knew where the island was or what it was called; he only knew it as ‘Adolf’.

I worked at the stone crusher where I was given a thirty-two-kilo hammer to crush the stones, but I was too young and weak to do that work, so they made me load sand into trolleys and take it to the shore, and when I was there I slipped off to hunt for mussels.

I avoided all the Germans, but there was one who picked on me. Every time I went past he beat me, and once he beat me so hard he broke my ribs. Later, I heard that his son had been killed in Russia, so he was taking out his anger on me.

I’m still angry with the Germans. It wasn’t just the fascists who beat us but the civilians [OT personnel] as well. When I saw the English planes coming over I wanted them to bomb Alderney with all my heart. Not a single British plane was shot down over Alderney while we were there because we prayed to God to look after them. All our hopes were with Britain to liberate us.

We suffered from fleas and sometimes my blanket was white with their eggs. They were so bad I don’t know how I slept. Between ten and fifteen people died every day, especially in the winter of 1942/43, when there was terrible dysentery. A loaf of bread was a matter of life and death, but I would still exchange my share of bread for tobacco, I needed cigarettes so much.

They used dynamite at the quarry to blow the rock out. On one occasion we were told to take shelter from the explosion, but the force of it came from exactly the opposite direction and I received the full blast. My ankle was hit by a rock and to this day I am lame. I couldn’t walk back to the camp, and an old Russian sailor hid me in sacking at the quarry for three days. He brought me water, but the only food he could give me was wild blackberries. I had to start work again to get my food rations. People helped me by loading the trolley and pushing it to the beach. First my foot started to swell, then the other leg started to swell and then my face. I would have recovered if the wound had been cleaned but there was no medical care. The Lagerführer’s method of curing people was to beat them. People were either dead or working; you couldn’t be ill.

Early in 1943, between six and seven hundred of the weakest people, including myself, were loaded onto the Xaver Dorscb, and more on another ship, the Franka. The plan was to take us to Cherbourg in one day, so they had packed the ships with as many people as possible. A severe storm shipwrecked both ships and they were pushed onto Alderney’s rocks by the waves. For fourteen days we were kept inside the wrecks with no bread and no water. Each day six barrels of soya flour mixed with water were distributed amongst the prisoners. The Germans didn’t go into the hold and they appointed the Russians to distribute the ‘soup’. The Russian ‘police’ always took one barrel for themselves, which meant that a lot of prisoners got no food at all. The prisoners crowded around the barrels, knowing that there might not be enough for the last in the queue. In the rush, about six people were crushed to death every day.

The Russian police then found a big long stick and stood on the ladder which led up to the deck and beat those who were near the front of the queue on their heads. These prisoners lost consciousness and fell, and the people behind them would rush forward and trample them to death. After the stick was introduced, the number who died went up to ten or more a day.

The most dreadful thing on this wrecked ship was the toilet. There was only one barrel for more than six hundred prisoners, and it was emptied only once a day. Because of the rough seas, the boat was moving all the time, and the excrement slopped over. In fourteen days at least four barrels were poured over the floor. No one was allowed out on the deck, and the air was so thick that if you had lit a match there would have been an explosion. I was sitting near the staircase leading to the deck. Everyone was wet with excrement and the lice multiplied so quickly you could collect handfuls under your armpits, but there was nowhere to drop them other than on your neighbour. There was no room to lie or stretch your legs. We were covered with wounds and our skin was eaten up with lice and sores.

The dead people were taken out of the hold by a rope around the neck, but the rope broke sometimes, so they changed the technique and passed the rope round the body. Then the Germans decided the bodies had to be buried with a priest. There was no Russian priest, so a Russian policeman who wanted to ingratiate himself with the Germans selected one of the slave labourers. This man had been a poet and a writer before the war, but he had been beaten by the Germans for stealing potatoes and he had gone mad. The Russian policeman told him to pray, and ordered all the other Russians to copy the madman. Fifteen corpses had been taken out of the hold and were laid out on the deck. For the first time we were allowed up onto the deck; we were wet with excrement. The Germans watched the ‘funeral’ and we knelt in circles around the corpses. The ‘priest’ started crossing himself and singing – not prayers, but a Ukrainian folk song. It was a farce. The Germans rewarded the ‘priest’ with bread. Then the corpses were thrown in the sea and we were sent back into the hold.

The next day we were taken off the ship. We were told to take all our clothes off and to leave them behind in the ship. We were each given a blanket smelling of horses, otherwise we were naked. I cut a hole in the blanket and put it over my head. Two or three days later, after the ship had been repaired, we were finally taken to Cherbourg.

Pothugine’s suffering didn’t end with his departure from Alderney. In Cherbourg he was beaten by one of the Russian policemen from Alderney with a metal rod and lost all his teeth. For the rest of the war, he could only eat wet bread and mashed cabbage.fn10

Another Alderney survivor who lives in Zaporozhye, Ivan Sholomitsky, was trapped in the other wrecked ship, the Franka. He still works at one of the steel plants, and in his lunch hour he came to Pothugine’s flat and gave his account. He thought that there were about three hundred prisoners trapped with him for ten days amongst drowned bodies in a half-submerged ship.

Ted Misiewicz has lived in London since the war. He was born in 1926 in a village in eastern Poland, from where he was taken for slave labour in 1942 and sent to Alderney. He never returned to Poland after the war, but came to England from France. After a period in the British army, he trained to be an architect.

My village of Niemilla was about twenty-eight kilometres from the Russian border. It was at the conflux of two rivers and had very poor, sandy soil, and there was only subsistence agriculture. Life was never easy. The rivers regularly flooded and then we were cut off on both sides. We lived a very introverted life, but we were never bored because there was just too much to do; everyone worked from sunrise to sunset. There was no electricity in the village but we did have a radio and in the evenings everyone would come and gather round it to listen.

We would spend all year preparing, pickling and storing food for the long winter months. February was usually the worst month – sometimes we only had boiled salty potatoes to eat for a whole week at a time. At these times it was very tense in the house. There was a cold wind that was so sharp that any exposed skin would dry and crack up.

The first sign of spring was the appearance of the sorrel, and my mother would send me and my sister to gather it for soup. The next sign was the new potatoes; only then did you start living again.

Misiewicz’s village heard on the radio that Germany had invaded Poland in September 1939, but they believed the war would pass them by, much as the First World War had done. They saw the Russians cross the border (Poland was partitioned by the Molotov–Ribbentrop pact in August 1939), but the soldiers didn’t come to the village. Then came the German invasion of the Soviet Union in 1941: ‘We knew about the German invasion from the Russian newspapers. For days we could hear distant guns rumbling. We saw a lot of Russians withdrawing; they marched barefoot with their boots hanging around their necks. Then the Germans attacked and the Russians were thrown back; there were tanks and abandoned armaments everywhere. Many of the defeated soldiers slept in the forest.’

The war moved on, leaving the village in German-occupied Poland. The Germans intervened in village life only for work duty and requisitioning foodstuffs. In spring 1942 the Germans gave the village a labour quota, and the sixteen-year-old Misiewicz was selected: ‘Only three of us went from our village, and each of us took a small bundle of food. We were made to sign papers which said we had volunteered to work for the Germans, and we were then loaded into cattle trucks with the Russians. On the journey we were given no water, and some of the Russians even drank their urine. I think the journey lasted ten days.’

After stopping briefly at a camp in Kestelbach in Germany, Misiewicz was put on a train for St Malo. He reached Alderney by boat in June 1942, in a transport of 1500 prisoners. He was among the first to arrive at Norderney camp.

I was taken to start work in the quarry. At first I was working as an interpreter, because nobody could speak a word of German in our group. But I quickly found out that it was a privileged position which also obliged me to beat people, and I resigned.

There were eight Russian and Ukrainian police chosen from among the slave workers. One of them was a tiny fellow called Boris who was only seventeen, but he was a real little animal. Of course you could never fight back if you were being beaten by one of them. All you could do was fall down, curl up and hope they would only kick you a couple of times. If you fought back you were dead. I suppose they had to beat people, it was their job.

A lot of the workers were very heavy smokers, and they would often trade the little pats of margarine we occasionally got for cigarettes. The old men told me that these boys were sentencing themselves to death, that they were committing suicide by giving away their food. They were right – after a few weeks they looked like living skeletons. The wind blew them down and they didn’t get up.

There was no money, so prisoners bartered. There were fights, and gangs who bullied other prisoners. There were some beatings in the barracks, and some murders as well. The Germans didn’t give a damn. The body would be thrown outside the barracks, and in the morning the Germans would collect it. Different nationalities kept together; we Poles were a small minority.

Misiewicz fell ill. His body began to swell, and the camp commander’s interpreter, Jean Soltisiak, who was a Pole, took pity on him because he was one of the youngest in the camp. Soltisiak saved Misiewicz’s life several times over the next few years. He managed to get him small jobs in the camp, thus sparing him the hard construction work and giving him more time to hunt for food scraps. One of these jobs was cleaning the home of the camp commandant, Karl Tietz. Misiewicz had been almost beaten to death by Tietz once, and now his job included cleaning up the blood after other prisoners were beaten. He also had the task of clearing the tables: ‘So started my slow recovery. The Germans would always leave food on their plates and they always had more bread than they needed. I never ate it all at once, but put little pieces of food away in a small suitcase.’

Then Soltisiak got Misiewicz an even better job, in charge of the baths.

During the winter I made a small bed next to the hot-water boiler with some roofing felt and nailed it round my bed to make it very cosy and warm. I finally began to live again. I was quite comfortable and for once I even had enough food. In return for food, I used to let the cooks use my machine room for meetings with their French girlfriends.fn11 Even the Germans liked me, because there was a small spyhole in the machine room and I would let them watch the French girls bathing.

We had big political discussions, and sometimes we had parties. One night the hospital staff supplied some ether which we made into ‘punch’. Luckily I was late and there was very little left to drink. The next day several people who had drunk the punch found they had gone blind. One of the cooks whom everyone, including the Germans, liked never regained his sight; the Germans injected him with something in the sick bay and he died. They told me to write to his relatives to say he had died defending his country.

In July 1943 a Spaniard who acted as postman came running up to me shouting my name; I was one of the lucky few to have received a letter, and he thought I would be pleased. He was not to know what it contained. It was from a cousin who had fled to Austria. He wrote to tell me that our village had been destroyed and everyone had been killed by the Ukrainians. It hit me very hard. My brother, my mother and my sister had all been killed. My sister’s breasts had been cut off before she was burnt. My cousin had survived by hiding underwater in the roots of a tree.

In October 1943, Misiewicz was transferred to Sylt camp without explanation. ‘That was very bad news. To be honest, in Norderney or Helgoland we could live. It was hard, but we could survive. In Sylt, you died. We were made to work very hard on the Westbatterie, pouring concrete and bending the steel reinforcements. One time we worked non-stop for a day, a night and another day. They brought us soup from time to time. It was raining. By the time we eventually returned to the camp, ten people had died.’

Misiewicz is the only slave labourer known to have escaped from Alderney during the Occupation.

I honestly don’t remember why I decided to escape, because it was an enormous risk; escapees were always recaptured, and they did not just kill them, they tortured them.

One evening at sunset when the dogs were being fed and all the SS were in the outer compound, I decided to go. Other slave labourers posted a lookout and spread two blankets over the first wire. I climbed up over the second wire and jumped down into a field of beetroot. I crawled on my stomach along the furrows for a hundred yards until I found the road.

Misiewicz went to Norderney camp to find Soltisiak, but as luck would have it, his friend had just left Alderney for the Continent. Other friends told him that another transport for the Continent was due to leave in about three weeks. For three days and nights he hid in an old fort above the camp. One night, the German anti-aircraft guns used the fort for target practice, terrifying Misiewicz. He then spent two weeks hidden in the roof of one of the barracks in Helgoland camp while the Germans searched the island for him.fn12 Friends brought him food. ‘Eventually my friends came and told me the transport was in the harbour. They told me a Belgian would meet me at 7 p.m. This Belgian told me I should wait until a particular Russian name was called, and then I should board the ship. I was so nervous I completely forgot the name, and it had to be called out three times before I got my wits together. I reached Cherbourg safely.’

Norbert Beermart insisted that before he talked of his experiences on Alderney, we should first visit the tiny Chapel of Our Lady of the Old Mountain, which sits on a small hill overlooking the old Flemish market town of Geraardsbergen in Belgium where Beermart was born and to which he has retired. It is crowded with the paraphernalia of devotion, and the walls are lined with marble plaques commemorating a prayer answered, or a loved one lost. When sixteen-year-old Beermart disappeared from his home in 1940, his mother put up a plaque asking for the safe return of her son. In 1944, when she had lost hope, he arrived in the town in an American Jeep. It was a miracle, she believed, a gift from Our Lady of the Old Mountain.

Beermart’s miraculous survival is a continuing source of boyish delight to him, and he regales any willing listener with his wartime stories in the bars of Geraardsbergen. He has revisited Alderney frequently, and he recounted his story wearing a baseball cap emblazoned with the logo of Alderney Channel Islands Yacht Club. ‘For me,’ he says, ‘the war is never over. Some people don’t like to talk about it, but I talk about it all the time. I was a little hero in this town when I returned.’

Beermart was born into a family of six children, and was apprenticed to his uncle, a butcher. The skill was to stand him in good stead in the camps. On 18 May 1940, he and his older brother, along with thousands of other men of military age, were told to leave their homes and join the Belgian army in France. They walked to the border, but in the chaos of German bombing, Beermart was separated from his brother. A French soldier took the boy under his wing, and together they travelled south through France, away from the advancing German army. When the Frenchman rejoined his regiment, Beermart was forced to steal to eat, and before long he was caught and imprisoned in a camp full of Spanish, Belgian and Russian refugees who had fled across the Pyrenees after fighting in the International Brigade in the Spanish Civil War. A few months later the French handed the camp inmates over to the Germans, to fulfil demands for labour. Beermart found himself amongst a contingent of twenty-four prisoners boarding a ship in Cherbourg in December 1940.

We sailed to Alderney and disembarked with no food, no German guards and no shelter. It was very cold. We could have been in Africa for all we knew. Before 1940, the furthest I’d ever been from Geraardsbergen in my life had been a few miles with my friends on our bikes.

The next day it was lovely weather and we began to look around. All the windows in the houses had been shattered and the doors were broken off their hinges. Books were scattered everywhere. There was no sight of any Germans.

The first man to die on Alderney was an American called Williams; he was born in 1915 in Boston, Massachusetts. I know because I made his cross. He’d fought in the International Brigade. There was a motorbike lying on its side by the road. It was a booby trap, but he didn’t know and he went over to pick it up and it blew him up.

After several days without any food or water, about twenty Germans arrived with some horses and we started to build Norderney camp. One of the horses stepped on a mine and was killed, and I volunteered to cut it up. That’s how I started working in the kitchen.

My best friends were Polish. They’ve been an unlucky nation but they have a lot of character. On Alderney they believed that they had to survive, and they never doubted that sooner or later they were going to get their own back on the Germans. I learnt to speak Polish and Russian on Alderney. Janek Novak was Polish and he worked in the kitchen with me; he was one of my best friends.fn13 I took Janek’s shoes off his feet before he was dead because I had no shoes. I arrived on Alderney a small boy. I was growing and I had to steal clothes and shoes. Now it seems terrible, but you stole anything. Many times I feel guilty about the things we did.

Those of us working in the kitchen were a strong gang of friends, and we all had the same tattoo done. I designed it and the Poles used three needles and made colours from the ashes. Some prisoners died from the tattoos going septic. The Germans wouldn’t let you do tattoos but we did it to prove we were stronger than the Germans.

There were about 150 women on Alderney who were brought over from France in batches of about thirty at a time. They were either French or Portuguese workers. They had been hand-picked by the Germans in France; they were all under twenty-five and beautiful. It was like a cattle market the morning after they arrived when the German officers looked them over. If they ‘stayed’ with an officer all they had to do was clean his room, make his bed and sleep in it. If they refused to do that, they ended up working in the camp kitchen, peeling potatoes. I know of only one woman, a Belgian, who held out against the Germans, and she eventually committed suicide.

A lot of us used to go and use a peephole in the washing room to look at the girls bathing. We used to pay the head of the washroom in cigarettes, which were the currency of Norderney. There was one very beautiful Polish girl, and I think she knew we watched her. All the men with good jobs such as the Ukrainian guards, the barbers and the kitchen staff used to go and look at the women.

The Germans had plenty of parties on Alderney. If a prisoner was good at dancing or singing or playing the guitar, they’d be called in to entertain the Germans. Even the gypsies danced for them. Anyone who had a special skill survived. I remember one night the gypsies danced for us around the bonfire. It was beautiful. The Russians were good at dancing and singing. We even played football with prisoners from Sylt. We weren’t allowed to talk to them. The Russians played football in bare feet but they were very good.

The big boss was Adler, who was drunk from morning to night, and all the time he played with his gun. Heinrich Evers, the deputy camp commandant in Norderney, was a small man and a sadist; I saw him beat people to death many times. I was forgotten on Alderney as if I was just a dog hanging about in the kitchen; nobody could remember what I was doing there.

There were a lot of suicides. Once, a former jockey went into a minefield. The Germans offered to help him get out by going to fetch a map of the mine positions, but he refused and danced on the mines until he was blown up. It took him twenty-five minutes.

Every day you saw perhaps as many as five people die. At the beginning of 1943, ten people were dying in Norderney daily. I saw several people being buried in one grave. Other prisoners took the clothing off the corpses so there was no means of identifying them or their nationality. Three men worked full time as gravediggers, and four men in a truck used to go round picking up the dead bodies from the fields or from where they had fallen.

Beermart eventually managed to get transferred to Cherbourg. Once there, he slipped through the German net and joined the French resistance.

It was the French Jews who christened Alderney ‘le rocher maudit’ – the accursed rock. Eight hundred of them were brought to Alderney to work for the OT after they had been rounded up in the ‘rafles’ (raids) organised by the Vichy government. They were all married to ‘Aryan’ Frenchwomen, and were thus designated ‘half-Jews’ by the Germans. Instead of being sent to the gas chambers, they were detailed to work as slave labourers. They counted themselves the lucky ones; a few food parcels managed to get through to them from their families, and few of them died.

Albert Eblagon, now a frail nonagenarian, was lucky enough to be sent to Alderney because he was married to an Aryan; his unmarried brother died in Auschwitz. Most of the French Jews sent to Alderney were older than the Russian slave workers. Many of them were middle-aged or even elderly, highly educated, and had held prominent positions in pre-war France; they included a large number of doctors, the former head of the Pasteur Institut, a parliamentary deputy, First World War veterans, civil servants, writers and lawyers. Eblagon had been a publisher’s travelling salesman; he says modestly that everyone else was much more high-powered than himself. The Jews’ consignment also contained a handful of Chinese, Arabs, Spaniards, Italians and Greeks who had been included in the rafle of Marseilles to augment the numbers.

The first transport of French Jews arrived on Alderney in July 1943. They were put in Norderney camp, in a separate section from the Russians. Accounts vary as to their working conditions. Some of the Russian survivors claim that the Jews were better treated, and Albert Eblagon says that less than a dozen French Jews died, although the low death toll may have been due to the fact that they were only on the islands a few months, at a time when most of the hard construction work had already been completed. But according to statements made to French war crimes investigators in 1944 by two doctors who had been among those transported, Henri Uzan and J.M. Bloch, the treatment of French Jews was as cruel as that meted out to the rest of Alderney’s slave workforce.

In August 1943 [Uzan’s report reads], we were loaded onto boats with kicks and shouts. The Germans spat on us from the bridge above us. We stayed like that for twenty-four hours. It was a very rough crossing for everyone. A German, Heinrich Evers, greeted us with slaps, kicks and threats of his revolver. I was carrying two suitcases, and a soldier grabbed them from my hands. We had to march to the other end of the island. There were among us many who were more than sixty years old and who were ill. We were put to sleep in barracks without straw or blankets – only some dried leaves to sleep on. In the morning we discovered that we were covered with lice.

All our luggage was taken except one blanket, one shirt, one pair of trousers and shoes. Then a very watery soup before we began work at 5 a.m. the following day. We had to be inspected by a German doctor; we waited naked for four hours. The German doctor came for twenty-five minutes to inspect four hundred men; he picked out the unfit. There was a quick interrogation by the German company to which I had been assigned. They asked if I had any skills. I said I was a doctor, and the German just dictated to the secretary that I was a ‘labourer, unskilled’. I was assigned to carry fifty kilos of cement. It was the same for a deputy, a famous lawyer, a pianist of world reputation, a lieutenant colonel.

Dr Uzan mentions the use of one particularly ‘cruel and sophisticated’ technique. The Germans would order a prisoner to beat a fellow inmate – even his best friend. If they didn’t beat hard enough, another friend would be chosen.

Dr Bloch told the investigators how some work teams had to work sixty hours at a stretch, with only twelve hours’ rest.

An Armenian who was already very weak and on the list of ‘unfit’ fell from the scaffolding from a height of two metres. His comrades were forbidden to go to him; he was left without cover in the open air. At about 11 p.m. a German officer went to him and said that he was not yet dead. He died at about two o’clock in the morning from cold. We never knew where he was buried.

One deportee was blinded by kicks in the eye, another’s arm was paralysed after he was hung for two days by his arms. Another had his ear ripped off. I think about eighty per cent of deportees were this badly treated.