Chapter 2

Handwriting Development and Comparison

2.1 Introduction

Forensic document examiners routinely give evidence relating to disputed authorship of handwriting and signatures (Ellen, 2006). This chapter looks at both the process and the product of handwriting and how it is examined by the forensic expert. The examination of signatures is considered in the next chapter.

Inevitably, the attention of the forensic handwriting expert is focused on the product—that is the handwriting itself—and relatively little attention may be given to the process that caused the handwriting to be created. Having said which, handwriting experts often infer some of the immediate factors affecting the process from the product. For example, the speed of writing may be inferred from its apparent fluency, or the naturalness of the handwriting from letterforms that are typical or otherwise. More distant factors, such as those affecting the development of handwriting in an individual, may be less thought about, but in general terms they are just as important because they underpin and justify the handwriting experts' ability to do their job. For these reasons, it is important to understand why we write the way we do and why we all differ from one another in this complex skill.

2.2 The process of writing

Handwriting is a highly developed skill that we usually start to acquire during early childhood which then develops during subsequent years through adolescence and early adulthood. By early adulthood handwriting has matured into a settled style that will remain largely unchanged for many years until such time as factors that are detrimental to handwriting production start to affect it, such as illness and old age.

Handwriting acquisition is one of many skills that are learned during the early years of life. There are a number of theories that set out to explain general skill acquisition, be it riding a bike, playing the piano or learning to write. These theories have the aim of connecting what we see in skill development in individuals with an understanding of how this correlates with what is happening in the brain. In particular, there is the idea that specific areas of the brain are pre-destined by virtue of their neurological connections to carry out particular functions (for example, see (Fodor, 1983)), suggesting that certain parts of the brain are associated with different sub-elements of the handwriting process (see Box 2.1).

One of the cornerstones of handwriting analysis is the observation that handwriting varies both for a given writer and between writers. This concept of variability is central to some theories of how psychological processes work (for example see (Siegler, 2002)) and is profoundly distinct from the frequently encountered notion of finding commonality in psychological processes that aim to show underlying factors shared between individuals. Siegler emphasised the need to embrace variability in order to obtain an understanding of the differences that occur in psychological processes, a view shared by Miller (2002) who reviewed the potential gains to be made from studying variability in cognitive processes. Indeed, Z. Yan and Fischer (2002) suggest that careful, detailed examination of variation is not only desirable but crucial for illuminating the dynamic nature of learning and development in individuals. Their work, based in part on studying the learning of new routines, showed that performance of a task did not show a simple linear improvement with practice over time, but rather periodically suddenly got better and also sometimes worsened depending on various factors that could be a reflection of the task or the person or both—it found variability both within and between participants in the dynamics of their ability to learn.

Specific areas of the brain are involved in handwriting production and these show up on brain scans, as has been demonstrated in many studies. For example, the speed of writing was examined using PET and various areas of the brain cortex were found to be implicated in the control of pen speed (Siebner et al., 2002). The handwriting of skilful and less skilful children has been examined using fMRI, with particular areas of the brain being associated with differences in skill (Richards et al., 2011). Exactly how the various factors involved in handwriting fit together to enable its smooth and efficient production will now be considered.

2.3 Models of writing production

Models of writing production (as opposed to handwriting production) have been dominated by the ideas put forward by Hayes and Flower (Gregg, L.W. & Steinberg, E. R., 1980), who proposed that writing consists first of a planning stage, then a translating phase and finally a reviewing phase. Roughly, these equated to the creation of ideas (the planning phase), their transformation into words which are set down (the translation phase) and finally the review phase (by reading what has been produced) to check that the product is suitable. Thus, often handwriting as an act is the product of a creative process that determines what to write and how it is to be written. If the words are dictated by someone else or are copied then the planning phase does not apply. Changes in the capability of the writer occur as the translation phase improves with greater handwriting skill, changes that occur during childhood and into adolescence. These are reflected in the development of overall writing skill with increasing age (McCutchen, 2000).

The mental resource within which writing (and handwriting or indeed typing) is carried out is referred to as working memory, which is considered to be a mental mechanism for storing and processing information in the short term and thus providing an interface between incoming perceptual inputs, outgoing actions and longer term memory processes (Baddeley, 2003). The concept of working memory is one that implies a limitation on what ‘thoughts’ can be stored and processed successfully at a given time. Its relevance to handwriting production is that there is potential competition between the needs of the cognitive (what to write) and the motor (how to write) in terms of working memory resource. It follows from this that the more the physical process of handwriting can be automated in a writer, the more this frees up the working memory for the cognitive elements of writing. For this reason, much of the effort in teaching handwriting to children, after the initial phase of learning letterforms, is focused on increasing speed and automaticity thereby minimising the need for working memory to deal with the mechanics of handwriting and allowing greater capacity for the more conceptual elements of writing (Berninger et al., 2010). Such changes have been found to occur in most children where kinematic factors in handwriting were measured and to change significantly with age (Rueckriegel et al., 2008). The handwriting from participants with ages ranging from 6 to 18 was analysed using a digitising pad (see Box 2.2) to measure various parameters of handwriting production. The authors found a significant correlation between the age of the participants and the velocity of writing, automaticity, movement variability and pen pressure. Automaticity was measured by the number of changes of velocity in pen strokes during handwriting production, providing evidence that there are improvements in the motor elements of handwriting as children get older.

Greater automaticity, greater speed and reduced variability all suggest that older writers are using highly learned processes to generate handwriting movements, while their younger colleagues are still having to think about how to write. This is consistent with developing neurological patterns of movement that are called upon routinely by the writer and that require little conscious input. While changes in the appearance of the handwriting cannot be inferred from these kinematic factors alone, these findings show that the process of handwriting changes as children get older.

Handwriting production is usually considered to be largely a linear process in the sense that information is passed sequentially from one stage to the next (as opposed to parallel processing where information is passed from one stage to two or more subsequent stages at the same time). Handwriting is also thought to be a modular process with high-level ideas (what to write) passed down towards the peripheral motor output (the act of writing itself), with certain regions of the brain being associated with different modules of the process, a model which is in keeping with and an extension of the model of writing production described by Hayes and Flower (Gregg, L.W. and Steinberg, E.R., 1980). Van Galen (1991) suggests that the stages are idea creation, leading to concepts, from which come phrases and then their component words, then the graphemes (the mental representation of letters, such as B) and their different letterforms (allographs, for example using b rather than  ), which finally lead to the relevant pen stroke movements.

), which finally lead to the relevant pen stroke movements.

The effective execution of handwriting requires an element of planning to make the process efficient, with the brain forming a motor plan to move the muscles and joints of the hand and wrist and fingers in a coordinated way to make appropriate pen stroke movements (but see also Box 2.3 for other modes of writing production).1

Motor planning is determined by the sequence and shape of the letters that are about to be written. This in turn may be based on the recall of appropriate syllable structure for the word (within the constraints of a syllabic language such as English). Kandel et al. (2006) found that syllable structure constrained motor production in writing, with inter-syllable boundaries being associated with a slowing down of pen movement. This suggests that at this level, the syllable (a unit based on the sound of the word) plays a part in the dynamic of the writing process. The combinations of letters within syllables, particularly those that occur more frequently, might become learned as a single ‘unit’ rather than as a sequence of individual letters. In this context, similar movements may produce different outcomes, such as when the letter pair e-l and the single letter d are written (Figure 2.1). Wing and Nimmo-Smith (1987) found that the kinetics of pen movement when writing e-l are not the same as the kinetics when writing d, even though the pen path is similar in both instances. This suggests that there is an element of learned, anticipatory context-dependent production in the writing process, consistent with the syllabic element of word construction. In other words, once we know what we are about to write, the letter groupings that make up the syllables of the about to be written words ‘queue up’ as part of the planning process, awaiting their production on the page as each set of movements in sequence turns the thought into handwritten actions.

Figure 2.1 A similar pen path is used for writing the letter d and the letter pair el.

The movements themselves are, in a skilled writer, rapid and highly time-coordinated (Longstaff & Heath, 2003). The pen movements have a very tightly controlled dynamic component that ensures that movement changes occur in the right sequence and at an appropriate velocity, without which pen strokes might be of inappropriate size or might not be correctly constructed in relation to one another. The rapidity shows that the movements are planned and held in readiness to be executed in a time-sequenced manner, with a series of overlapping discrete movements generating a smooth continual movement (Morasso et al., 1983).

Handwriting movements are constrained by the anatomy and neurological capability of the writer's arm, wrist, hand and finger movements as a result of which some pen movements are preferred to others as they are more readily executed (Thomassen et al., 1991). The smoothness and consistency of movement of arm joints and muscles improves during childhood and is often of an adult standard at the age of about 11 or 12 (Chiappedi et al., 2012)—an age at which handwriting skills are still being perfected.

Handedness in handwriting production is another consideration and is of particular interest to the forensic expert. This is because if the handedness of the writer of a piece of handwriting can be determined this may provide important evidence of authorship, since for many people writing with the unaccustomed hand is difficult, leading to poor fluency (Figure 2.2). Evidence relating to handedness may be available from the pen movements made (Figure 2.3), since left-handed writers often prefer clockwise and right-to-left movements due to the biomechanics of the muscles and joints that are in mirror image to those of right-handed writers, who generally prefer to use anti-clockwise and left-to-right movements (Meulenbroek & Van Galen, 1989). It is perhaps noteworthy that not all writing systems follow the same pattern of left-to-right alphabetic construction. For example, Arabic is also alphabetic but written right to left, and other writing systems do not use alphabets at all (see Box 2.4).

Figure 2.2 Handwriting from same person using accustomed and unaccustomed hand.

Figure 2.3 Handwriting with clockwise and right to left t-crossbar (left-hand example) and anticlockwise and left to right t-crossbar (right-hand example).

The effect of losing the use of the dominant hand (for most people this is the right hand) has been studied clinically, but it is difficult to generalise over what the impact will be on a given writer as each case is different (Yancosek & Mullineaux, 2011), albeit many writers are able to write reasonably well with subsequent retraining using the unaccustomed hand if given enough practice (Walker & Henneberg, 2007).

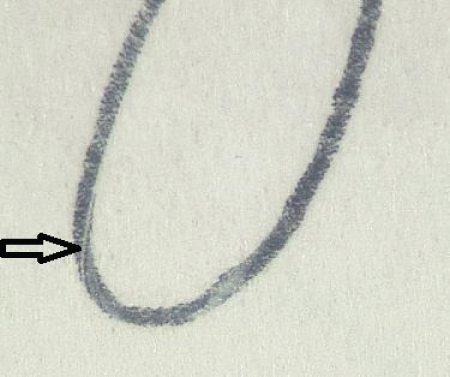

When examining a piece of handwriting, the direction of pen stroke can often be determined by a careful examination of the ink line. In particular, the presence of striations within a ballpoint pen ink line can show the direction of travel of the pen, with striations going from the inside to the outside of a curved pen stroke even if the degree of curvature is slight (see Section 2.8.2). Inferring the handedness of a writer should always be done with caution as a small minority of writers can use both hands equally well and not all writers use all of the handwriting traits associated with left- or right-handed writing.

The models that describe the process of handwriting production show just what a neurologically complex process it is and provide clear evidence for the scope of variability in handwriting both between different writers and within the writing of the same person. A consideration of the many external factors that influence the learning of handwriting will now show additional forces that affect the development of handwriting within an individual from childhood through adolescence and into adulthood.

2.4 The learning of handwriting in young children

Learning to write is regarded as one of the most important skills that a child can acquire in early school years. Given the opportunity, children as young as 12 months old like to make marks on paper with writing implements. The use of a writing/drawing implement begins in young children when they can pick it up and manipulate it in such a way as to make a mark on a substrate (usually paper). The ability to make marks and their associated meanings, which in time come to be attributed to such marks, are the embryonic stages of drawing (Kellogg, 1969). Kellogg found that the early scribblings of young children can be deconstructed into a number of common elements consisting of various orientations of lines, circular movements, zigzags and other similar movements. These movements are in essence those which are to be found in handwriting later on in a child's development.

One thing that is striking about the process of learning to draw is the use of repeated sets of movements by the child to replicate in a formulaic manner frequently drawn images (Hollis & Low, 2005). Rather than re-invent a new series of pen strokes to draw a house or a face, the young child first learns a sequence of strokes needed to produce a satisfactory image and then uses the same set of movements each time they draw that item. Of course, because of the inherent complexity of the motor and cognitive elements involved in drawing, no two drawings are absolutely identical; instead, they will show variation from one to another. Rueckriegel et al. (2008) showed that the automaticity of both drawing and writing movements increased as children got older, providing additional evidence for a maturation process in the motor components of both handwriting and drawing.

The idea that the ability to draw and the ability to write are connected has been widely investigated. Those who are proficient at drawing are also likely to be proficient at producing handwriting, as found by Bonoti et al. (2005). They showed a correlation between handwriting and drawing skills in 182 children aged 8–12 years old, scoring handwriting in terms of placement, conforming to taught styles and size and scoring drawings, such as a man or a house, to set descriptors of how they were drawn.

A number of general aspects of development in younger children's handwriting have been studied, including legibility, speed and size (Blote & Hamstra-Bletz, 1991; Graham et al., 1998; Rueckriegel et al., 2008). Handwriting speed and legibility in children aged 6–15 was studied and were both found to improve year on year, although the rate of change varied with, for example, those aged 6–10 improving more rapidly than those in the next few years (Graham et al., 1998). Graham et al. also found that legibility generally improved with age, but that again the rate of change was not even, with little improvement in the younger years and greater improvements in later years. Handwriting size tends to start larger in those learning to write, decreases in size over the next few years and thereafter some children start to write larger again (Blote & Hamstra-Bletz, 1991).

Developmental processes of handwriting change in older children attract relatively little attention in the literature (Weintraub et al., 2007). However, neurological problems in children during these formative years can lead to a range of problems in later years in terms of the legibility and correctness of the handwriting formation and its speed of execution (van Hoorn et al., 2010a). One of the reasons why handwriting attracts little attention in the later phases of development is that handwriting ability is no longer perceived as being a constraining factor on learning for most children and older children are thought to be less amenable to instruction in the case of any dysfunction. This may be a short-sighted view, however, as a child's handwriting is unlikely to improve on its own but rather requires help, and later academic performance may indeed be influenced by the ability to execute handwriting effectively (Feder & Majnemer, 2007).

The way in which the writing implement is held at the paper surface is one of the last links between the internal (biological) processes of handwriting production and its physical manifestation on the paper. Tseng (1998), for example, identifies over a dozen pencil grips in children in the 3–6 year old age range, although the number of grips used falls off with increased age as inappropriate grips are discarded by those who tried them. This is echoed by the findings of Schneck and Henderson (1990) who identify ten grips that are associated with different levels of development in children, with different grips sometimes used for different tasks, such as writing and colouring in, and with gender differences between preferred grips. Nevertheless, some children will find particular grips more comfortable than others and this is likely to be in part determined by the suppleness of their finger and wrist joints (Summers, 2001) and hence the amount of pen control that a particular grip gives the child (Burton & Dancisak, 2000). Changes in pen grip are almost bound to lead to increased variation of the handwriting since this will influence the overall fine motor movement. Indeed, the movements of muscle sets involved in handwriting have been found to be less variable in older children who can write more quickly than younger children (Naider-Steinhart & Katz-Leurer, 2007).

A significant proportion of children will have some difficulty learning to write (Hoy, et al., 2011) and a variety of techniques is used in an attempt to improve a child's handwriting, focusing often on general visual and motor integration and fine control skills (Feder & Majnemer, 2007). The techniques used will also vary depending on the root cause of the problems, such as those attributable to various medical conditions, but the main criterion for referral is generally simply the teacher finding it difficult to read the child's handwriting (Hammerschmidt & Sudsawad, 2004). A method for measuring handwriting capability is central to such techniques and a number have been devised; they are summarised in Box 2.5.

The process of learning to write, therefore, contains many factors that have the potential to affect a child's handwriting. The earliest experiences of acquiring the skill of handwriting are now passed on into the middle school years of adolescence, where yet more changes will occur.

2.5 Handwriting in the adolescent: the origins of individuality

A person's handwriting can change at any time, but generally from early adulthood through to early old age a person's handwriting is fairly stable. However, the handwriting of adolescents and those entering old age is more likely to change over time. In the former group this is because the handwriting has not yet fully developed and in the latter it is because there may be a general skill deterioration associated with old age.

Little has been published about handwriting development as it occurs in adolescents, spanning the years from about the age of 10 to late teens. By the time most writers reach the age of about 10 they have acquired a reasonable degree of fluency and speed in the production of handwriting (Weintraub et al., 2007). However, that is not to say that in these writers the developmental process stops; far from it, for once the essential elements of the skill of handwriting have been mastered, it is then possible for the writer to manipulate it to their own ends, rather like learning the basics of tennis strokes and then developing and perfecting them to fit best with your own physical capabilities. For handwriting, development during adolescence may be in terms of general features, such as the speed and legibility of the handwriting (Graham et al., 1998), or in more specific details of the letterforms used, introducing shapes and forms of letters that were not taught them at all but adopting new features for any one of a variety of reasons—from peer compliance to parental guidance (Sassoon, 1990).

It is during the adolescent years that the handwriting of an individual goes through some of its most transformative stages, becoming, on the one hand, more consistent and, on the other hand, more individual. Allen (2011) found that the handwriting of children becomes increasingly consistent with age and at the same time also becomes more differentiated from their peers. This was shown by taking a series of letterforms and determining how their use changed over time in children aged 5–18. Within-writer variability was greatest in children aged about 10 or 11 years old suggesting a period of experimentation and change, whereas individualisation was greatest in the older children, as shown by a strong tendency for samples of handwriting of a given individual to be similar one to another but different from that of his or her peers.

It is obvious that most adults' handwriting is markedly different from that taught to them as children not just in terms of general appearance and skill but also when considering specific letterforms. Changes to handwriting over the years of adolescence are largely gradual but can occasionally be more sudden, especially when a writer intentionally incorporates new features into their writing during periods of experimentation. The additional effect of striving for increased speed will also drive some of these changes as the writer becomes not only quicker but adopts a handwriting style that is more efficient in terms of pen movement, letter joining and other relevant dynamic factors. Despite this, some writers will produce handwriting of a particular style that is not so dynamically efficient, sacrificing speed for appearance. The many factors impacting upon the handwriting of an individual are particularly likely to have an effect at this time, when the basic skill of handwriting has been acquired but before it has been fully developed into a mature personal style. Given the complexity of the effects of these factors on one another, it is not surprising that at the end of the period of adolescence, each individual child's handwriting has become more distinctively their own.

The handwriting of adolescents causes some difficulties for the forensic expert since its immaturity, variability and any imitative components from within the taught or peer groups can all have short-term impacts on its appearance (Cusack & Hargett, 1989). These factors must be considered carefully when interpreting the significance of observations in casework, and there is a particular need to ensure that any specimens of handwriting are as contemporary as practicable with the handwriting in question so as to minimise differences that can occur over short time periods. This is usually less critical when considering the handwriting of adults, which will be considered next.

2.6 Mature handwriting of the adult

In Sections 2.4 and 2.5 the importance of learning and developing handwriting was emphasised in relation to its impact on how people end up writing as adults. The teaching of handwriting has changed over time and varies from place to place. This leads to general style differences and also to some character-specific variations being found in the writings from those taught in different places and at different times. In many countries, an elaborate version of handwriting was traditionally taught, such as copperplate. Whilst this may have been elegant and aesthetically appealing, over time simpler styles were considered more appropriate in terms of the ease with which children could learn to write. These educational and cultural influences will lead to an increase in variation between writers who are taught different so-called copybook styles.

Some differences are attributable to the prevailing method of teaching at a particular time in a particular country. A number of systems are outlined in the book by Huber and Headrick (1999: chapter 8) showing styles of handwriting from a number of countries. For example the following would be regarded as unusual by someone taught to write in the UK (Figure 2.4): the letter W constructed from four separate pen strokes—this is commonplace in many taught to write in West Africa; the use of the capital form of the letter R in lower case writing is a habit found commonly in the writing of those taught in Ireland; the numeral 7 written with a crossbar is widely regarded as a European affectation although increasingly common in the UK; the number 9 written with a markedly curved tail and often using two pen strokes is common in eastern Europe (Turnbull et al., 2010).

Figure 2.4 Examples of national handwriting characteristics (see text).

Such features are not necessarily universal, but they do tend to occur with greater frequency in some groups than others and hence provide another source for between-writer variation in a multi-cultural society.

The effects of these cultural influences are shown by the findings of Cheng et al. (2005) when examining the writings of three culturally distinct groups, namely Chinese, Indian (writing Tamil) and Malay (writing Arabic) people in Singapore, learning to write English as a second language. These three handwriting systems have very different appearances and this was reflected in the romanised English written by individuals from these different backgrounds. For example, the stress on straight lines in Chinese, the formation of dots in Arabic and the curvature of the strokes in Tamil were reflected in the writing in English.

As far as the handwriting expert is concerned, therefore, it is important to be aware of changes in taught handwriting styles over time and in different places and to make any necessary enquiries when examining handwriting that shows such influences. There would then be a need for information to be supplied about the nationality and age of those providing handwriting specimens so that the expert can interpret the findings giving appropriate significance to the features present.

2.7 The deterioration of handwriting skill

A variety of factors can lead to deterioration in handwriting including various medical conditions, the effects of alcohol and some drugs that affect the central nervous system, as well as increasing old age. Generally, these factors impact on either the cognitive or the motor aspects of handwriting production, disrupting at some point the pathway from thought to movement of the hand and fingers. Underlying these conditions is brain function, which is required for handwriting production (see Box 2.1).

While illness might generally be thought a factor in the handwriting of adults and, more specifically, the elderly, in fact there are a number of medical conditions that can affect handwriting in young people. Children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) are likely to show poorly constructed letterforms associated with reduced motor control (Fuentes et al., 2010). Cerebral palsy will also significantly affect a young person's handwriting (Bumin & Kavak, 2010). Even relatively minor neurological dysfunctions (MND), such as developmental coordination disorder, can have an impact on the handwriting of young people (van Hoorn et al., 2010b) in terms of legibility, speed and appropriate formation.

Handwriting errors that occur as a result of brain damage, typically after a lesion caused by a stroke, are of a number of kinds and reflect the areas of the brain affected and their role in the processing of information from cognitive to motor output. Errors can occur at the level of allograph choice, in which the style and case of the letters are determined, and damage to this process would be expected to lead, for example, to an inappropriate mixing of upper and lower case letters (Debastiani & Barry, 1989). Once the style and case are chosen the next stage is to adopt the appropriate set of movements to write the letter and errors at this point will lead to substitution of correctly formed but incorrect letters (Destreri et al., 2000). A lesion that disrupts the motor pattern will produce handwriting that is poorly formed so that it tends towards an illegible scribble (Margolin & Wing, 1983). Other medical conditions can cause very small writing, known as micrographia, including loss of blood flow to certain parts of the brain, a condition which can be reversible (Perrin et al., 2005).

Micrographia is most often associated with patients with Parkinson's disease. Indeed, micrographia is a well-established clinical indicator of Parkinson's disease with about three-quarters of patients showing it as a symptom (Bryant et al., 2010). Bryant and colleagues show that it may be possible to at least partially overcome micrographia using grid lines to help the writer to adjust letter size. Medical intervention, such as levodopa prescribed to alleviate the symptoms of Parkinson's, may reduce the micrographia (Tucha et al., 2006a) and subsequent stopping of the medication leads to a worsening of the effects on handwriting production. The effects of levodopa on handwriting performance may be noticeable just minutes or hours after being administered (Poluha et al., 1998).

Patients with multiple sclerosis do not normally have difficulty writing but have a tendency to write more slowly (Rosenblum & Weiss, 2010). This will be reflected in the apparent fluency of the handwriting as indicated by the evidence of pen speed across the paper.

A more general deterioration of writing capability is commonly found in patients with Alzheimer's disease or associated mild cognitive impairment with slower, less smooth and less consistent handwriting (Yan et al., 2008), with both the content (such as misspellings and semantic substitutions) and its motor execution being affected, with the former often occurring before the latter as the disease progressively worsens (Croisile, 1999).

Because certain medical conditions are manifested in handwriting, it may be possible to tentatively diagnose such conditions from an assessment of a person's handwriting. For example the handwriting errors that typically occur in those with Alzheimer's may be used (even posthumously) to ascertain a person's capacity to understand, for example, a document signed by them (Balestrino et al., 2012). Indeed, there is a link between handwriting and general cognitive dysfunction in the elderly in terms of handwriting ability (Ericsson et al., 1996), with deterioration of the signature being more resistant to such effects than general handwriting.

Not all medical conditions that impact on handwriting necessarily have an obvious neurological cause. For example, one study has shown that cirrhosis of the liver can affect a person's handwriting, albeit the mechanism linking them has not been established (Mechtcheriakov et al., 2006). Conditions that are more in the domain of psychiatry, such as obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD), have also been shown to have some subtle motor effects that are then transmitted to handwriting leading to slower, less well-automated handwriting (Mavrogiorgou et al., 2001).

The automatic nature of skilful handwriting is such that it might be expected that blindness, particularly if its onset occurred after the skill had been acquired, will affect the appearance of handwriting. However, there is a need for visual feedback in the process of handwriting and the absence of this will cause errors to occur (Arter et al., 1996).

The elderly are often some of the most vulnerable in society and therefore the target of criminal activity. For this reason the handwriting capabilities of the elderly need to be understood by the handwriting expert in order to be able to interpret findings in cases involving old people.

Elderly, but otherwise healthy, people do not generally have a great need to write extensively but rather tend to make infrequent, short jotting-type notes (van Drempt et al., 2011). In such circumstances, it is not surprising that in the absence of regular use of the skill the authors found that handwriting was particularly variable in terms of parameters such as baseline position, inter-word spacing and slope. Handwriting speed gets slower as people get older beyond the age of about 65 (Burger & McCluskey, 2011) and in older people the task and even the type of writing implement used can affect handwriting speed.

In only a few instances has the forensic significance of these medical factors been considered by handwriting experts. For example, the effects of Parkinson's disease (Walton, 1997) and of recent blindness (Masson, 1988) have been reported. However, only broad categories of effects can be reported due to the variable responses of people to medical impacts on their handwriting, making it difficult to generalise from one case to another.

In forensic casework, the most frequently encountered intoxicant is alcohol. The effects of alcohol on handwriting have been studied and often show a diminution in the control of pen movement rather than specific errors in handwriting production. A variety of spatial measures including word length, heights of letters, heights of ascenders (such as the left side of a letter h) and descenders (such as the tail of the letter y), and the spacing between words have been shown to be significantly affected by alcohol (Asicioglu & Turan, 2003). The reasons for the effects of alcohol on motor functions shown in handwriting are not fully understood but they are similar to the effects of cerebellar dysfunction in the brain (Phillips et al., 2009).

The forensic impact of alcohol on handwriting has been considered (Beck, 1985; Galbraith, 1986) but as with the effects of medical conditions, intoxicants have differing effects or similar effects of differing degrees from one person to another, particularly depending on their tolerance of alcohol.

The effects of caffeine have been reported (Dhawn, et al., 1969; Tucha et al., 2006b). Dhawn and colleagues also report on the impact of methamphetamine, chlorpromazine and phenobarbitone in terms of time taken to write, spacing and size of letterforms. Caffeine and methamphetamine are stimulants and lead to faster handwriting, whereas chlorpromazine and phenobarbitone are depressants and slow handwriting. Tucha and colleagues found that caffeine produced faster handwriting with smoother acceleration and deceleration of the pen as measured using a handwriting digitising tablet. These effects were dose related, so the more caffeine taken the greater the effect.

In another study, Tucha and Lange explored the effects of nicotine on handwriting (Tucha & Lange, 2004) and found increased velocity and greater fluency in handwriting production in both smokers and non-smokers with nicotine intake.

There is very little information in the literature about the forensic effects of drugs on handwriting. Commonly encountered drugs, such as caffeine and nicotine, are likely to have marginal effects on letterform but may alter writing speed to some degree. Other drugs that have greater effects on the relevant neurological pathways may have more profound effects on handwriting, especially when they are prescribed to improve an underlying medical condition. Nonetheless, handwriting experts need to be aware of the possibility that these various factors might impact on a person's handwriting.

2.8 The forensic analysis of handwriting

Up to this point in the chapter, the focus has been on the process of handwriting. Now the product of handwriting will be considered in detail since it is this that the forensic handwriting expert will examine in the real world of casework.

The forensic handwriting expert may be asked to examine all kinds of cases ranging from relatively minor fraud involving small amounts of money through to murder and terrorism. Casework inevitably involves examining material that is constrained by practical considerations. For example, the amount of questioned handwriting in dispute is usually a given, be it an anonymous note, a telephone number scribbled down hurriedly or a death threat. However, an investigator may be able to exert some degree of control over the obtaining of samples of specimen handwriting of known authorship to compare with the questioned handwriting. Requesting specimen samples from a writer provides an opportunity to get as much as is reasonable to expect, or a search of premises may provide other samples. But in reality, the handwriting expert will only have a relatively small amount of handwriting (in comparison to the whole handwritten output of an individual) to examine; typically a handful of questioned documents and a few samples of specimen handwriting—although some cases may be much larger and some even more restricted in terms of available evidence.

The vast majority of cases involving a forensic handwriting examination are centred on a comparison between the disputed handwriting and samples of specimen handwriting from one or more people who are suspected of having produced the handwriting in question. (The forensic examination of handwriting to identify authorship should not be confused with examinations that aim to identify the personality of the writer, often referred to as graphology.)

Of course, each case is unique, but there are a number of steps involved in a forensic handwriting examination that form an appropriate procedure to ensure it is carried out properly. English uses a number of general styles of handwriting that are usually called script (small unjoined letters), cursive (joined letters) and block capitals. Small letters are usually referred to as lower case and capital letters as upper case. Block capital letters are generally dissimilar in form from the letters used in script and cursive handwriting and they cannot be effectively compared. Likewise, the act of joining letters can have an impact on their appearance and so comparing script with cursive handwriting is not ideal. Many writers mix the styles of handwriting that they use. Even skilled writers may join some letters and not others, and some writers may mix upper and lower case letters. As far as the handwriting expert is concerned, the key point is that a comparison can best be done between letterforms that are comparable, usually called a like-with-like comparison. If a case is submitted in which the styles of handwriting to be compared differ, then there needs to be some dialogue between the expert and those submitting the case to try and improve the basis of the examination.

2.8.1 Specimen handwriting

There are two kinds of specimen handwriting that can be obtained in casework. The first is known as a request specimen, since it involves the investigator asking a person to provide a sample of handwriting. The details are typically dictated to the person supplying the handwriting sample and, depending on their cooperativeness, the aim of the investigator is to obtain a reasonable amount of handwriting. The amount will in part be determined by the case. For example, if there is only a single jotted telephone number in question, then obtaining perhaps 10 or 12 repeated versions of that phone number in a specimen is likely to be adequate. But if the questioned handwriting consists of many pages of handwriting, obtaining even one version as a specimen may be too much to expect.

As has been noted above, the process of handwriting is most natural when it is done quickly and with the minimum of conscious input. A specimen of writing written in such a way should be a reasonable sample of a person's handwriting. However, if the writer deliberately disrupts their normal handwriting by consciously trying to alter their handwriting, in other words disguising it, then obtaining such a specimen may not yield a satisfactorily representative sample of their handwriting. To overcome this, it may be necessary for the investigator to try to delay or distract the writer in order to take their focus away from the act of disguising their handwriting and causing them to write more naturally.

If a person is not cooperative in providing a specimen of handwriting at request, it may be possible to obtain a non-request sample of writing from their everyday lives, such as address books, letters, forms or diaries. The handwriting on such documents can generally be assumed to have been written naturally (or at least without intentional disguise), although the circumstances of writing can vary from writing carefully at a table to scribbling something down while standing, for example. A non-request specimen, therefore, has the advantage that it is likely to be naturally written. However, it has the disadvantage that there is no control over its content, so if the questioned handwriting is in cursive handwriting and an address book is supplied containing entries in block capitals and numerals, the specimen may well be naturally written but also largely irrelevant. In addition, there is always a concern over who in fact wrote a non-request specimen and, related to that, whether all of the handwriting is by one person or whether more than one person has written it.

If both request and non-request specimens of handwriting are available, this is often the ideal situation since the former can be controlled to ensure that relevant details are present and the latter should at least be natural and show the normal handwriting skill of the person concerned. In addition, if there is a concern that the requested handwriting is not natural, this can often be confirmed or refuted by checking it against the non-request sample.

The quality of the specimen handwriting obtained is a crucial factor in determining whether a handwriting expert can reach a conclusion over the authorship of a piece of questioned handwriting. If the specimen supplied by an investigator is inadequate for one reason or another, the expert must take this into account and consider the option of asking for more samples before committing themselves to any opinion.

Handwriting undergoes relatively little change during adulthood, but in adolescence and as writers move towards old age and its associated medical conditions, another factor comes into play when considering specimen handwriting, namely time. If a questioned document was written when someone was in their late 80s and suffering from Parkinson's disease, then a diary written by them when they were in their 50s may well be of little use. Likewise, a specimen of handwriting from a person aged 16 may not be ideal when compared to a questioned note written when they were 13, since their handwriting may well have still been developing during that time. Obtaining contemporary specimens may therefore be very important depending on the case, and again a dialogue between the expert and the investigator may assist.

The writing implement of choice for handwriting specimens is usually the ballpoint pen, but it must be borne in mind that the implement used can affect the handwriting and this may be a factor that the expert needs to consider when assessing the evidence in a case. For this reason, it is necessary to briefly consider writing implements and what influence they may have on a person's handwriting. (A more detailed review of ink examination can be found in Chapter 6.)

2.8.2 Writing implements

In general, the choice of writing implement (or at least conventional writing implements) does not affect the process of writing but it might affect the appearance or the fluency of the writing (Mathyer, 1969). The use of unconventional implements such as a paint brush may well affect the structure of the handwriting. Nonetheless, by far the most commonly encountered writing implement is the ballpoint pen. The viscous ink is held in a reservoir behind a rotating ball bearing (Figure 2.5). Rotation of the ball causes ink to coat the ball and be deposited on the paper. Ballpoint pen lines tend to be impressed into the surface of the paper, the extent of which is partly determined by the pressure applied to the pen by the writer. The ink is oil-based and often has a lustrous, thick appearance when viewed under magnification. The deposit of ink may sometimes be uneven, with excess ink occasionally being deposited to form so-called goops. If the pen is unused and the ball is open to the air, the ink may dry on the ball such that when next used this dry ink is lost, producing an inkless start to the pen stroke. Most importantly, many, but not all, ballpoint pens produce striation lines within the ink line. These have the property of indicating the direction of the pen stroke in curved ink lines, with the striation going from the inside to the outside of the line in the direction of motion (Figure 2.6). This may yield important information about the pen movement—for example whether a letter O is written clockwise or anticlockwise. It is because of this kind of information that the ballpoint pen is the implement of choice when obtaining handwriting samples at request.

Figure 2.5 The tip of a ballpoint pen (x8 approx.).

Figure 2.6 Striation lines in a ballpoint pen ink line (x10 approx.).

Other pens use a hard rotating ball but with different ink formulations. For example, gel pens use inks that are water-based. Other pens use nibs that are fibrous, such as felt tip pens (Figure 2.7). Some felt tip pens have relatively narrow nibs, but some are much wider—for example, marker pens—and the broad nib makes normal handwriting movements more difficult. Handwriting produced with such writing implements may be structurally different to that produced with more conventional writing implements.

Figure 2.7 A felt tip pen nib (x8 approx.).

Traditionally, the fountain pen was the implement of choice, but such pens are less and less encountered. They too use water-based ink and the ink line is often uneven along the edges. Pencils are occasionally used, typically producing a readily recognisable grey writing line.

Casework can involve handwriting produced with all manner of things ranging from paintbrushes to marks scratched onto wooden surfaces to lipstick. Such unconventional implements inevitably inhibit the normal, natural handwriting movements of the writer and due consideration of this must be given when assessing findings. In addition, the posture of the writer in such cases is also often unusual, such as standing up writing on a vertical surface or bending down writing on a flat surface at ground level. Again, such postural changes can require handwriting movements using unfamiliar joints and muscles and may impact on the handwritten product.

2.8.3 Pre-examination review

Before starting a full case examination, the expert should make sure that the material submitted is suitable given the question that has been asked by the investigator. If the material is not suitable, then the investigator should be contacted with a view to establishing whether there is a realistic prospect of improving matters. As noted above, the questioned and specimen handwritings must be comparable and the specimens must be as relevant as possible. However, there are often other preliminary considerations.

One of the most common problems is poor quality copy documents. Although most handwriting is in original form at some point (an exception might be signatures produced using a stylus on a touch sensitive pad as used by some delivery services, for example), some cases involve the examination of copy documents, that is documents that have been produced by photocopying, faxing, computer scanning or microfilming. The amount of detail that can be discerned from copy documents is always less than that from the original in terms of letterform and the fluency of the handwriting. A copy document that shows the handwriting so indistinctly as to make examination of it virtually impossible is clearly a severe limitation to a comparison such that the expert may feel it best to at least seek a better quality copy if available.

If after a preview of the submitted material the handwriting expert feels that a meaningful examination is possible, then the examination proper can commence.

2.8.4 The natural variation of handwriting

The forensic examination of handwriting is a painstaking process that requires a lot of patience on the part of the expert, an eye for detail and a comprehensive approach together with an unbiased, open mind as to the outcome. There are many sources of information in a piece of handwriting that help inform the expert about whether or not a questioned document was written by a particular person. Central to this assessment is the idea of the natural variation that is to be found in handwriting.

Variation in handwriting is its most important property and yet the one that causes the most problems. As was shown in earlier sections of this chapter, there is considerable scope for handwriting to vary both between different writers and within the handwritten output of the same person, attributable to the highly complex cognitive and motor processes involved. However, this does not mean that handwriting can vary infinitely—far from it. The automatic nature of handwriting in a skilled writer ensures that the writer generally produces letterforms that are similar but not identical from one occasion to another. In another sense handwriting is also constrained by the need for it to be readable, so there are conventional letterforms that are recognisable as conforming to expectations: a letter A must at least look like a letter A, irrespective of how it is constructed.

But in casework a forensic handwriting expert is confronted with relatively small amounts of handwriting to examine. Even with small amounts of handwriting, research has shown the scope for between-writer variability in, for example, English (Srihari et al., 2002) and Japanese (Ueda et al., 2009).

The variations to be found in handwriting generally occur along a number of dimensions. It is not necessary or possible to catalogue these letter by letter. Instead, an indication is given here of the kinds of feature that must be considered when analysing variation in handwriting. In addition, describing handwriting features using words alone is often awkward and hence diagrams are included unless the appearance of the letterform is very obvious from the description given.

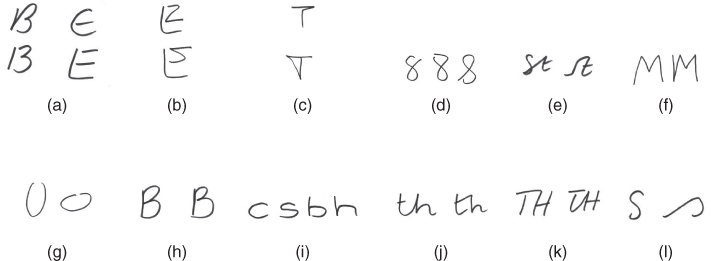

Letter construction has a number of different components. For example, the letter B can be written in one continuous movement or as two separate pen strokes, or the letter E written as a semi-circle with a second, central horizontal stroke or written as an L-shape with two further strokes (see Figure 2.8a).

Figure 2.8 Various letterforms (see text).

Characters of similar construction can themselves vary in the sequence of pen movements used to write them. Continuing with the letter E, the L-shape can be followed by the top stroke then finally the middle stroke or the middle stroke then the top stroke (Figure 2.8b). Similarly, the top stroke of the letter T may be written either before or after the down stroke (Figure 2.8c).

The direction of pen movement may vary and this can sometimes be determined, for example by examining pen striations (see Section 2.8.2). Some write their letter O in a clockwise direction (usually, but not always, left-handed writers), others write it anti-clockwise (most right-handed writers and also a significant proportion of left-handed writers)—see Figure 2.3 earlier in the chapter.

The direction of pen movement when writing the numeral 8 may vary, together with the point of initiation. The most common is to commence at the top right and move anticlockwise, the pen finally returning to the top right from the bottom left. But some writers begin at top left and may head anticlockwise or clockwise, and yet other writers start at bottom left (Figure 2.8d).

Most curved letters, such as the letter S, tend to be written starting at the top and finishing at the bottom. However, in a small minority of writers, the letter is begun at the bottom of the letter (Figure 2.8e).

As well as variation in curved movements, writers vary in the horizontal and vertical directions too. For example, some writers write the A-crossbar from left to right and others in the reverse direction. The initiation of many letters, such as M or N, with a down stroke is frequently encountered, but some writers omit the down stroke and commence with an up stroke (Figure 2.8f).

The proportions of written characters can vary both within themselves and also between various characters, although proportionality is usually fairly resistant to change. van Doorn and Keuss (1993), who focused on the repeated letter pair lele, found that there was a high level of spatial invariance when written under different circumstances (small, medium and large writing, with or without visual feedback).

Internal letter proportions are many and varied. For example, the letter O may be written as a tall, thin letter or as a squashed, flat letter (Figure 2.8g). This can be seen as a variation in proportion or as a variation in the shape of the letter. Another example of internal proportions would be the letter B with either both curved parts of roughly equal size or, as seen in many writers, the upper curve smaller than the lower curve (Figure 2.8h).

Some variations in proportion tend to occur in related groups of letters within the writing of the same person. For example, if a writer produces the letter y with a tail that is longer than the upper part of the letter, then it is likely that they will also produce the letters g and p in a similarly proportioned manner (Eldridge et al., 1985).

The shape of characters may also be connected; for example, a writer who produces a flattened, elongated form of the letter c may tend to produce a similarly flattened, elongated form of the letter s, and quite possibly the bowl elements of the letters b and h and so on (Figure 2.8i).

Thus, it can be seen that some features of writing tend to be somewhat generalised in the writing of a given person. This leads some to describe writing in very broad terms as, for example, rounded or angular.

Inter-character proportions vary too. The most common letter pair in English is th. In many writers, the two letters are of about equal height, but in a number of writers the t is routinely smaller than the h (Muehlberger et al., 1977). Not only can inter-letter proportions vary, so too can the way in which adjacent letters are joined. For instance, some writers join the letter t to the letter h via the tail of the t; others join to the letter h from the crossbar of the t, and some people do both (Figure 2.8j).

If capital letters are being hurriedly written, it is common for some letters to be joined. In this case, the joining often reflects the letter construction. So, for example, someone who writes the letter T top second will join to a subsequent letter from the end of the crossbar, whereas someone writing the down stroke second will join into the next letter from the bottom of the down stroke (Figure 2.8k).

Some letters can be written in more than one form or allograph. For instance, the letter s may be written as one curve or two (Figure 2.8l). Some writers may use one form, others the alternative and some may use both forms, often in a context-dependent way. The need to facilitate the joining from a preceding letter or the need to ease the joining to a subsequent letter can determine the usage of a particular allograph (Van der Plaats & Van Galen, 1991).

Other components of handwriting that can vary are size and slope. In most cases, size is not particularly constrained, but when required to do so people can make their writing either larger or smaller. When writing on a blackboard, for example, the writing is not only larger but also requires the writer to adjust to writing on a different surface and at a different geometrical orientation to that usually used when writing at a desk. However, such changes do not significantly alter the appearance of the writing. Slope is fairly constant for some writers, but others may vary their slope markedly.

Another way of describing handwriting variation is to refer to schemes in which handwriting has been classified in some way. One such scheme was devised by Eldridge and colleagues (Eldridge et al., 1984) with the stated aim of focusing on the variability of handwriting both between and within writers. Its underlying purpose was to inform handwriting experts about feature frequency. The study considers the letters d, f, h, k, p and t and it examines these in requested samples from 61 adults, many of whom were from an educated background. The classification scheme used is very complex with often ten or more variants described for each letter. For example, the elements of the letter f are dissected by number of strokes (two categories), top of staff shape (three categories), top of staff direction (two categories), bottom of staff shape (three categories), bottom of staff direction (two categories), crossbar position (three categories) and crossbar curvature (three categories).

Similarly, Muehlberger et al. (1977) looked at the letter pair th because of its frequency of use in English. Their scheme also was complex and looked at the height ratio of the th (four categories), the shape of the h loop (five categories), shape of the h arch (three categories), height of the t crossbar (four categories), baseline of the h (four categories) and shape of the t (five categories). The purpose of such studies was to provide some statistical data on the features described and to point a way forward for similar research. However, such schemes can only describe a very limited amount of the variability to be found in handwriting, and for this reason they are not used routinely in casework.

Handwriting classification schemes have been devised for a variety of purposes. Some schemes use feature descriptors that are, as far as possible, mutually exclusive, typified by ‘writer A uses form X’ and ‘writer B uses form Y’ for a given letterform (for example, (Hardcastle et al., 1986). Whilst, between-writer variability is determined by such schemes, within-writer variability may not be quantified to give, for example, ‘writer A uses form X 80% and form Y 20% of the time’ and ‘writer B uses the same two forms but form X 30% of the time and form Y 70% of the time’. In terms of writer identification, this more subtle view of variation is able to provide important additional information about the frequency of use of variants within the handwriting.

The diverse factors that affect the development of each person's handwriting from childhood to adulthood are, therefore, apparent in the basic letterforms used and the variations these show both between writers and within the handwriting from a single writer. The handwriting expert has to first observe these in samples of handwriting in casework and then has to interpret the significance of the observations in the context of each case situation. Studies of variation such as those mentioned above can help to provide some guide as to the frequency of occurrence of basic features in handwriting, but the subtleties of variability are much greater than such classification schemes can show, particularly when a single writer shows variation and different writers show different ranges of variation from one to another.

2.9 Interpretation of handwriting evidence

While close observation of the detail of handwriting is a necessary component of an effective forensic examination, it is not sufficient basis on its own to inevitably lead to a correct opinion of authorship being expressed. The link between observation and the resulting opinion is the interpretation phase of the examination. For a handwriting expert, interpretation requires experience to assess the significance of the many observations that are made, bringing together the various strands of the findings to reach a justifiable and defendable opinion that is capable of withstanding the glare of a court's spotlight as it seeks to assess the reliability of the handwriting expert's evidence.

Because interpretation is effectively a process that occurs in the expert's mind, it is difficult to devise procedures to ensure that the expert's thinking processes are correct. One way to gain confidence in an expert's view is for the interpretation process to be written down in the case notes, which can then be reviewed and checked independently by another expert. In other words, the checking procedure ensures that not only has a reasonable conclusion been expressed but also that the reasoning towards that conclusion is appropriate. If there is agreement in both of these elements then this provides reassurance and confidence that the first expert's interpretation is correct. Hence, the expert's opinion must contain elements that are capable of being demonstrated and explained so that there is a chain of evidence that can be followed and understood by others, from the question (‘Who wrote the document in question?’) to the opinion (‘He did or did not’). It is not acceptable for experts to simply expect the courts to accept their opinion because it comes from an expert.

2.9.1 Limitations to the evidence in handwriting cases

If there are limitations to an examination, these must be indicated clearly and their impact on the interpretation reflected in the conclusion reached. There are many factors that can limit the effectiveness of a handwriting comparison. The most obvious are the amounts of questioned and specimen handwriting. Given the wide variety of handwriting features that are used, clearly the distinctiveness of the handwriting will play a part. If the handwriting is not very distinctive, incorporating many more frequently encountered letterforms, then it may be that it is possible to identify the author only after examining quite a lot of such handwriting and assessing the range of variation across many features present in the larger volume of writing. But if a piece of handwriting is more unusual then it may be possible to identify its author even from a relatively small amount.

If for a given writer certain letters and numerals are particularly distinctive, then their presence or absence in the case material may impact on the conclusion that can be reached. In other words, if the questioned handwriting consists of very distinctive numerals 4, 5 and 6, but the specimen only contains examples of 1, 2 and 3, then the fact that the questioned handwriting is distinctive is of little consequence in reaching a conclusion based on an unhelpful specimen.

The distinctiveness of handwriting is affected by the kinds of factor discussed in earlier sections of this chapter, especially where and when a person learned to write. Any tendency for certain handwriting features to be more (or less) common in particular groups of writers (from a particular country, for instance) obviously has the potential to affect the expert's view as to how unusual those features are. This all applies in particular to handwriting that has been naturally written. However, the writing process can be deliberately altered or disguised.

There are a number of commonly encountered strategies that are used when disguising handwriting. The nature and success of such strategies varies from person to person and so it is impossible to generalise on the effect the disguise will have. However, disguise is difficult to maintain due to the automaticity of handwriting in most adults. A deliberate, conscious effort to change handwriting may start off successfully, but as time passes there is almost always a tendency for the writer to revert back to their natural style. Of course, the writer may become aware of this and so it is common to see the level of disguise change over the document, sometimes more effective disguise, sometimes more natural. If it is possible to determine which are the more natural passages in the handwriting, for example those written with greater fluency or that are more ‘normal’ in appearance, then it may be possible for the expert to at least use these as more natural handwriting features.

The strategies used for disguise include some that are applied across all features, such as a change of slope or a change of size, some that are applied to related features, such as an exaggerated loop on letters such as f, g and y, and some that are letter specific, such as use of a completely different form of a letter. Use of the unaccustomed hand is sometimes attempted, but this is often apparent due to the lack of fluency this usually involves, since most writers are not able to write equally well with both hands. Skilful writers may attempt to disguise their handwriting by deliberately writing with less apparent skill and may also deliberately make the writing less literate by, for example, purposely misspelling words.

A change of writing implement can influence the appearance of handwriting, for example graffiti written with a paint brush on a wall as opposed to writing at a desk with a ballpoint pen on paper. Whether this is deliberate or simply a consequence of the case circumstances will depend on the situation.

Handwriting is affected by the age of the writer, particularly so in younger and older writers. In some cases this can limit the effectiveness of the comparison, especially if the questioned and specimen handwritings are not contemporary with one another. In those elderly people who have severe handwriting difficulty, the ability to write may change over very short periods of time and the variability of the handwriting may be so great that it is almost impossible to come to a firm conclusion no matter how much specimen handwriting is obtained.

Observations of the handwriting and interpretation of their significance in the light of any limitations lead to a conclusion that must take account of alternative explanations for the observations. This approach to interpretation will now be discussed.

2.9.2 Reaching conclusions

Over the years a number of ways of looking at the interpretation of forensic evidence has been advocated. A detailed discussion of this topic can be found, for example, in Aitken and Taroni (2004). However, the handwriting expert generally has to consider a small number of possible situations with regard to the examination—often simply coming down to (i) the suspect did write the document in question or (ii) the suspect did not write the document in question. The expert must weigh the findings (derived from the observations) against the competing propositions with a view to determining which is best supported by the findings. It is not necessarily the case that all the findings will point in the same direction. Rather, it is sometimes the case that at least some findings will support one proposition and others an alternative proposition. In addition, some findings will be more significant than others and thus carry more weight when deciding which of the competing propositions is best supported by the overall evidence. Knowledge of how handwriting is likely to vary, the effects of age and the effects of where and when people were taught to write—all of the factors discussed in this chapter—inform the handwriting expert's interpretation in each casework situation.

The limitations of the case often affect the degree of certainty with which the expert is able to reach a conclusion. Forensic evidence is not required to be black or white. Indeed the courts require expert witnesses to be able to express an opinion and this often involves a view on how likely alternative explanations are. This must all be conveyed carefully in the wording of the report and for this reason it is common practice to have a scale of opinions that reflects the degrees of certainty available.

There have been various scales put forward over the years but most capture at least four levels of opinion and some have several more. The four major points on the scale consist of:

- Conclusive opinions, where the evidence is so overwhelming that only one interpretation is acceptable, with the alternative(s) being so unlikely that they can be discounted.

- Sometimes the evidence falls a little short of this very high standard, often as a result of case limitations, and in this circumstance the evidence is typically described as strong with alternative(s) being unlikely but not so unlikely as to be discounted—in other words there is a small element of doubt.

- If the evidence is weaker still but with one explanation being somewhat more likely than other explanation(s), but the other explanations not being by any means capable of being ruled out, then the evidence is often described as weak—in other words it is indicating which evidence, on balance, is the most likely given the observations and limitations.

- Finally, in some cases the evidence is too close to call for the expert to come to a conclusion at all, in which case the evidence is inconclusive and no alternative is favoured above any other and so the evidence could be regarded as neutral.

Opinions that fall short of conclusive are not an admission of failure by the expert to ‘get the right answer’ but rather are a very important part of the expert's role in determining the strength of evidence available from the material examined. Because of the nature of the interpretation process by the expert, it is perhaps not surprising that the use of computers to assist in the decision-making process in handwriting comparisons has been advocated, and this will be looked at next.

2.9.3 Computer use in interpretation

In the field of automated handwriting recognition, much work has been done to try to describe the written line as a mathematical function. In order to analyse handwriting mathematically, there are two components that can be measured. The first is the static component, which is the image of the completed handwriting or signature. The second component is the dynamic component, which can measure parameters such as the dimensions of the signature, the length of the written line, pen velocity over the paper, times when the pen is lifted from the paper and the pen pressure. Further measures can be calculated from these, such as the acceleration of the pen as it speeds up after starting a pen stroke and slows down as it comes towards the end of the pen stroke. Devices capable of measuring the dynamic components of handwriting and signature production are usually known as handwriting tablets (see Box 2.2).

Bridging the divide between this work and the classification of writing are studies such as that of Marquis et al. (2005), which uses mathematical techniques to convert shapes of handwriting on the page into mathematical expressions. Using this kind of approach, they showed that the letters O from three writers were different in their mathematical form. There was variation within the mathematical renditions and thus the possibility of ‘misattributing’ outliers, when looking at single examples, cannot be ruled out. Further work by Marquis and colleagues looked at similarly analysed transformations of the loops of the letters a, d, o and q from 13 writers (Marquis et al., 2006). They found discrimination values of about 70–80% for the letters a, d, o and q. Different loops were found to have different values for discriminating between different pairs of writers, as would be expected from the complex nature of writing. For example, the shape of the loop of the letter o was less discriminating than the loop shape of the other three letters studied, whereas the shape of the loop of the letter d was the best at discriminating between writers.

In a similar vein, Ling (Ling, 2002) measured 10 elements of cursive writing, such as word spacing, the space between the ascenders of the letters t and h in the th letter pair, the space between the sides of the letter u and so on. Ling also found that no one feature was able to provide discrimination between the writings of the 10 participants. Rather, he finds that a feature that discriminates between two given writers may not be so useful when discriminating between two other writers or even one of the original pair and a third writer.

A number of studies, such as that of Srihari and colleagues (Srihari et al., 2002), has shown that various algorithms can be used to examine handwriting samples offline (that is, from the static image rather than the additional dynamic information that can be obtained using a digitising tablet). The purpose of his study was to test the hypothesis of handwriting individuality in adult handwriting, a hypothesis that has come under scrutiny following various legal challenges to expert evidence in handwriting in the USA, summarised in Srihari et al. (2002). As Srihari recognises, the algorithms used may share some elements with those that forensic experts use, but they are not identical with them.

How do studies that aim to convert handwriting into mathematical constructs link in with classification studies that have the same aim, namely to give more objective data of the frequency of occurrence of handwriting features? Even the simple th letter join studied by Muehlberger and colleagues (Muehlberger et al., 1977) produced a detailed series of categories that overlapped depending on the variants present in a person's handwriting. Looked at in another way, given the advances in computing power in the years since such observation-based schemes were proposed, the absence of a computer-based approach to solving forensic handwriting problems is notable.

It is worth mentioning parallel studies that have attracted a lot of interest and that are aimed at handwriting recognition in the sense of determining what has been written, so that handwriting can be converted automatically to computer text, for example on hand-held devices with a stylus input. That there is a need for such conversion is interesting as it implies that there is still an advantage to handwriting in many circumstances, albeit clearly less need for it with the dominance of the computer keyboard, and indeed computers that have increasing capabilities of voice recognition. Contemporary studies of the amount of handwriting done by people of different ages shows that there is still a value in being able to write (van Drempt et al., 2011).

Such computer-centred studies have added support for the individualisation hypothesis. However, forensic casework is constrained by the real world and does not operate in the experimental laboratory. This is a crucial limitation on the applicability of the results of such studies. In essence, going from the general to the particular is fraught with danger. And computers are not (yet) able to factor in such human dimensions as intended disguise, the effects of intoxicants or the effects of illness on handwriting.

The value of computer-based studies is that they can help to contribute to the conclusions reached by handwriting experts about individuality, but it would be unwise to let computers replace the handwriting expert until such time that it can be shown that they can outperform the human expert across the range of case types encountered (Srihari & Singer, 2014).

2.10 Examination notes in handwriting cases

When examining any case forensically it is important to make full and comprehensive notes about what has been observed, what significance has been attached to the observations, what possible explanations have been considered and the conclusions reached. This provides an audit trail from the question to the conclusion and its description in the notes should be a close reflection of the observations and thoughts of the expert, providing evidence that the opinion has been reached in a logical and robust way.