Chapter 9

Indented Impressions

One of the functions of forensic practice that is sometimes forgotten is that it can provide intelligence information during an investigation as opposed to providing evidence in the aftermath of a crime. One area in document examination where this is especially true is in the examination of documents for indented impressions of handwriting or signatures. A typical case situation might be where an anonymous document contains some kind of threat and the investigator wants to know the origin of the document. One avenue to explore is to see whether there are any indented impressions of handwriting on the document which were created when some other (upper) document was written whilst resting on the threatening (lower) document. If the handwriting on the upper document contains information such as a name or address or some other detail which indicates its origin, then that can provide useful intelligence information for the investigator to pursue as a possible line of enquiry.

When writing on a sheet of paper that is resting on at least one other sheet of paper (for example pages in a pad, but the pages need not be bound together) the act of writing tends to produce a groove in the paper caused by the pressure from the ‘nib’ (be it the ball in a ballpoint pen, the fibrous tip of a felt tip pen or the traditional nib of a fountain pen). The amount of pressure applied on the writing implement varies from one writer to another. The pressure is relayed to the paper surface via the nib of the writing implement. An inflexible hard nib, typified by the hard metal ball in a ballpoint pen, will relay the pressure to the paper surface and this translates to a noticeable groove in the paper corresponding to the line of writing. A flexible fibrous nib in a felt tip pen will tend to absorb the writing pressure and so produce little by way of a groove in the paper surface.

The act of writing with, for example, a ballpoint pen, will often cause an indentation in the sheet of paper below, indeed it may be detectable several sheets below. If the writing pressure is large then the indentation on the lower page may be visible to the naked eye. However, it is often the case that there is no visible indentation on the lower page and yet there is disruption to the surface, the nature of which enables the handwritten details to be visualised.

9.1 Visualising indented impressions

There are two main methods used to visualise indented impressions of handwriting. A third method, sometimes portrayed in fictional accounts, is to lightly apply a pencil to the paper surface to help show up any deep impressions – this is not an appropriate method and should not be used.

It should always be remembered that a piece of paper has two sides. In those instances in which there is only handwriting or other details on one side, that does not preclude the possibility that there are impressions of handwriting on the other side of the paper.

9.1.1 Electrostatic method

There are pieces of equipment on the market that enable the document examiner to examine the electrostatic properties of a sheet of paper (see also Box 9.1). The use of these electrostatic devices has been universal in the document laboratory since the late 1970s and they are regarded as an essential piece of equipment for the forensic document examiner.

The reason for making such examinations is that the act of writing on an upper page causes disruption to the surface of the lower page and, as noted above, this disruption can sometimes be so large as to cause a visible indentation. This is also accompanied by a disruption to the electrostatic properties of the paper and it is these that are exploited by the components and processes involved in an electrostatic examination (Daéid et al., 2008).

Visualising the impressions is a matter of first placing the piece of paper on the device. It is typically held on a sintered metal bed (which allows a vacuum to be drawn through it) and a vacuum pump is switched on to ensure a good contact between the piece of paper and the device. The paper is then covered with a sheet of thin, transparent polymer film that is capable of taking the electrostatic charge produced by passing a high voltage corona wire a few millimetres above the surface of the polymer film. This gives it a charge and then the film is exposed to a (black) powder that is attracted preferentially to the charged areas of the plastic that coincide with the electrostatic disruption to the paper surface. The toner application can be either via a cloud spraying device or by combining toner with microscopic glass beads that carry the toner on their surface and which can be cascaded over the document manually.

Whichever method is used, the end product is a polymer film with black powder attached in areas that correspond to the writing impressions, and thus the handwritten details can be deciphered. The electrostatic image can be preserved (for evidential purposes) by placing a transparent adhesive plastic sheet over the polymer and toner and lifting the whole from the electrostatic device.

The fact that such devices work has been shown innumerable times. What is less certain is the underlying science that explains why electrostatic techniques work (see also Box 9.1). The physical deformation (the ‘groove’ whether visible or not) itself may not be the cause; rather the disruption to the paper surface caused by frictional forces between the upper and lower sheets appears to cause changes to the electrostatic properties of the polymer and paper combination and this, together with the toner materials used to develop the image, leads to a decipherable trace (Daéid et al., 2008). This apparent need for a frictional component is consistent with the poor results obtained from impacting devices, such as typewriters, where the impression is created not by a moving object (such as a pen) but by a striking object, such as the typeface, as it impacts the paper with no lateral movement.

Furthermore, good quality papers tend to yield the best results in terms of a decipherable trace, but if the paper is too heavily processed (such as a glossy magazine cover) the fibres on the surface may not be so readily disturbed leading to a poor result. Similarly, rough paper surfaces (such as blotting paper) tend not to give good results. The overall physical smoothness of the paper is also important such that, for example, heavily creased or crumpled paper will tend not to lie flat on the metal bed leading to poor contact between the paper and the polymer film.

High relative humidity (see also Box 9.2) is also often beneficial to electrostatic paper examinations (D'Andrea et al., 1996) (see also Box 9.2).

When examining a piece of paper on which there is visible ink-written handwriting, such handwriting will often appear as white on the electrostatic trace. Also, when examining the ‘reverse’ of a piece of paper that has either original ink-written handwriting or impressions of handwriting on the ‘front’ these may well show up on the electrostatic trace but in mirror image orientation.

9.1.2 Secondary impressions

Not only can electrostatic devices be used for visualising impressions caused by the straightforward act of writing on an upper sheet of paper, they can also be used in a number of related situations. If a first sheet of paper has indented impressions of handwriting on it, and that sheet of paper comes into contact with a second piece of paper which does not initially have those impressions, then the very physical contact between the two sheets can sometimes lead to the ‘impressions being transferred’ to the second sheet, forming what are often referred to as secondary impressions (Barr et al., 1996).

9.1.3 Determining the sequence of handwriting and impressions

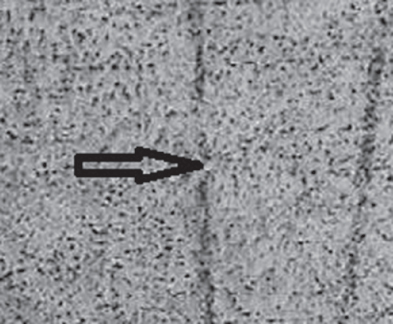

In some case situations a document can bear handwriting and also indented impressions of some other handwritten details, and a question may arise over whether the handwriting visible on the sheet or the impressions were present first. Sequencing handwriting and impressions of handwriting requires that they cross over at some points. An electrostatic examination shows that where the ink of some handwriting is already present on the surface of the paper and indented impressions are then created on that same sheet, the usual dark line of the handwriting impression on the electrostatic trace is interrupted by the presence of the ink (Radley, 1993) – see also Figure 9.1.

Figure 9.1 The dark grey line is typical of that produced by an impression and the pale tramlined line (running from bottom left to top right) is typical of that produced by an inkline on the paper. Where they cross (arrowed) any break in the lines may indicate whether the impressions were present on the page before the ink or vice versa (×3 approx.)

As noted in Chapter 3, signatures may be traced in such a way as to create a visible groove in the paper which is subsequently inked in to produce the forgery. If the inking in stage is done carefully, it may be difficult to detect the initial groove. An electrostatic trace of the area associated with the signature may show the presence of the groove and help to demonstrate how the forgery was created.

9.1.4 Examining multiple-page documents

Electrostatic examinations tend to work best if only one sheet is examined at a time on the device. This creates a problem if the document consists of multiple pages. If the pages are bound into a book then the page to be examined can be isolated and the remaining pages carefully moved away so that the page can be held on the device and covered with the polymer film. This therefore requires two people, one to hold the document in place and one to carry out the examination.

Alternatively pages can be cut from a document but only if permission to do so has been obtained from the investigator. If this approach is used, then it is important to identify the sequence of pages in the book before any are removed, for instance by writing a sequence of page numbers in the corner of each page.

Some pads are held together by spiral bindings. It is possible to manipulate these spirals by rotating them so that they can be removed. If this is done, again pages need to be numbered before dismantling the pad and permission from the investigator is needed.

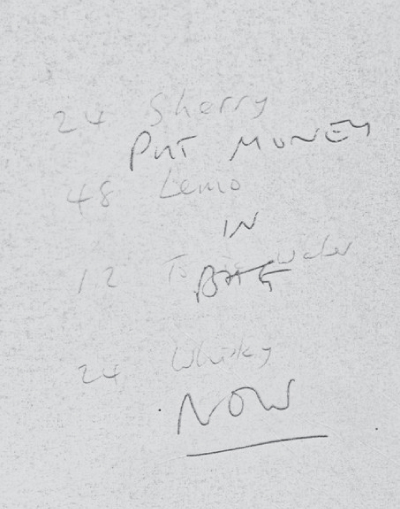

9.1.5 Deciphering electrostatic traces

The interpretation of an electrostatic trace can be straightforward when there is good contrast between the dark toner (showing the indented handwriting) and the general background (see, for instance, Figure 9.3 in the Worked Example at the end of this chapter). However, in some cases the handwriting is shown very faintly and it may be difficult or impossible to decipher the details with certainty. When deciphering faint impressions, it is important to try to avoid cognitive bias such as: Do the impressions say such and such? If there is uncertainty over what the impressions say then alternatives should be reported. For example: The impressions can be deciphered to read ‘0878 (5 or 6) (1 or 7) 33’. Similarly, where there are impressions present but they cannot be deciphered then their presence should be reported but their content left undeciphered.

Deciphering of words, in particular, is often context dependent. For example the letters ‘Chris’ at the start of a longer word may be very clear but the ending of the word may not be clear for some reason. However, if the surrounding words are concerned with Christmas then there is an inevitable temptation to ‘fill in the gaps’ and to read the whole word as Christmas. In these cases, care must be taken not to over-interpret what is seen and a common-sense view taken as to whether the unclear element is at least consistent with any filling in (for example if the word in fact was Christopher and not Christmas that would probably be obvious). Such deciphering is similar to the process of reading handwriting that is poorly formed and semi-illegible but which can be made sense of by the capacity of the human brain to ‘work out’ what has been written, not from each letter but from our knowledge of words, spelling, context and use of language.

As noted above, impressions of handwriting will often be detectable on not just the page immediately below that being written on but also on the next pages, commonly the third or fourth pages and sometimes beyond even those. If each page in a pad is written on, this means that on, say, the fifth page in the pad, there may be fairly clear impressions of handwriting from the handwriting on the fourth page, somewhat fainter impressions from the handwriting on the third page, even fainter impressions from the handwriting on the second page and perhaps yet fainter impressions from the handwriting on the first page. An electrostatic examination of the fifth page may reveal several sets of impressions from the pages above and these may well overlap one another making them very hard to disentangle to decipher. It may also be difficult to decide which impressions go together. For example, if there is a name and a telephone number revealed by the trace, were they written on the same sheet of paper (therefore suggesting an association between the name and the number) or were they in fact written on different sheets (and therefore do not necessarily suggest an association between the name and the number) and coincidentally show up roughly in the same place on the trace? Again, the human brain's capacity for language can assist and may suggest which entries might go together and this, taken with any differences in intensity of the impressions revealed by the electrostatic trace, might help make sense of the pattern of evidence.

When impressions are overlapping and difficult to decipher, it is sometimes a good idea to give the electrostatic trace showing the impressions to the investigator to see whether there are any details that appear to be significant to them. Of course, this again risks cognitive bias as the investigator is effectively looking for impressions that fit in with his or her preconceived ideas of what might be there, so it is essential that the eventual deciphering of any details of interest is done by the document examiner who can put forward any alternative interpretations where there is uncertainty and avoid misrepresenting the evidence.

Occasionally the revealed impressions are very faint and cannot be deciphered readily. One possibility is to carry out a second electrostatic examination and to superimpose the two traces obtained with the view of getting a darker combined trace.

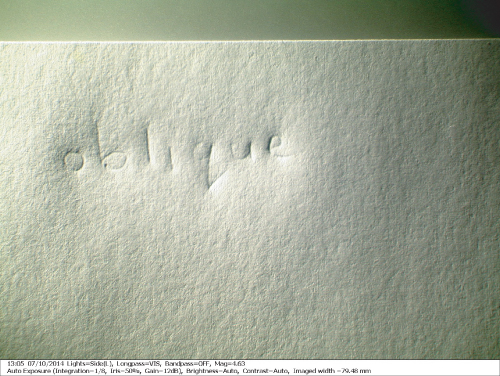

9.2 Oblique light

When examining a document for impressions of indented handwriting, the use of electrostatic devices is often the first process to be considered by the document examiner. However, there are some circumstances where the use of oblique light is more effective. The oblique light method for detecting impressions requires simply the illumination of the paper surface with a strong light source (such as light from a fibre optic) shone at a grazing angle to the paper surface (Figure 9.2). Any reasonably deep (visible) impression grooves in the paper will cast a shadow due to the grazing angle of the light, which can be photographed as a record of the evidence. The deciphering can be done at the time of the examination but the photographic record should show, as far as possible, those details that are deciphered.

Figure 9.2 Indented impressions revealed using an oblique light source to produce shadows created by the deep impression.

As noted in Section 9.1, deep impressions that produce easily visible indentations in the paper surface are not always well visualised using electrostatic devices. By their very nature, indentations that can be seen with oblique light vary in depth from barely detectable to very obvious. The less deep impressions are very likely to also be visualised using an electrostatic device. This is important when the expert is confronted by a lot of pages to examine (such as a thick pad of paper) and when searching for any pages that might have any impressions at all. By their very nature, writing pads can be written on at any page and pages can be readily removed, so to examine every single page using the electrostatic method would be very time consuming and sometimes time is critical in an investigation – such as in a kidnapping. Using an oblique light source to (relatively) quickly examine each page of a 200-page pad for any faint signs of impressions might enable attention to be focused on a small proportion of the pages for further electrostatic examination – broadly, an oblique light examination may take seconds per page, an electrostatic examination will take several minutes per page.

As already noted, oblique light is often the only method that enables deep impressions of indented handwriting to be visualised and recorded. Impressions caused by other factors, such as typescript, are again best examined using oblique light (see Section 9.1). One case situation that occurs now and again is the examination of very glossy paper, such as is found on magazine covers. Electrostatic techniques do not always work well with such paper and oblique light is made more difficult by the considerable reflection of the light from the shiny surface. If the impressions are deep enough, it may be possible to take a cast of the impressions using a very fine-grained casting material of the type widely used by forensic practitioners that examine toolmark impressions. When dry, the cast can be viewed with oblique light to emphasise the impressions, which are now in relief to the background, to assist with the deciphering process.

Recording impressions viewed with oblique light is done photographically. Getting the ideal lighting angle is important to make the impressions as clear as possible. If, for example, a whole page of A4 paper bears impressions, it may be difficult to cast a strong enough light at an ideal angle to record the impressions across the entire page in one photograph. Instead, it may be better to photograph several areas of the page, making sure that the photographs record slightly overlapping regions of the page so as not to omit any details. The recording of the impressions serves not only as a record of what the document examiner found but also allows such evidence to be presented to others at a later date in a court hearing, for instance.

9.3 Case notes in indented impressions cases

The primary purpose of notes in such cases is to record what has been done and what has been deciphered. All findings, including negative findings, should be recorded. For example, the use of oblique light may be tried and may well reveal nothing visible, but the process and outcome can be briefly noted. If an electrostatic method is used, then the humidity and temperature conditions can be recorded. It is essential that an electrostatic trace can be linked back to the relevant document from which it is derived by appropriate labelling of the trace.

The deciphering stage can be carried out in a number of ways. For example, a photocopy of the trace can be annotated and the deciphered details written adjacent to each entry. It is essential that any uncertainty in the deciphering is clearly recorded and that this corresponds to the way that the results are presented in any final report or statement. If it is unclear which deciphered details belong together, then it is essential that this is indicated in the manner in which they are represented in the written report to avoid misleading the investigator.

It is a common occurrence to carry out an electrostatic examination of a document and not observe any evidence of impressions of handwriting. Such negative findings can also be retained since it is a record of what was found and if called into question subsequently, the trace can be produced as evidence of what was not found.

In cases in which oblique light has produced evidence, a photograph of the impressions should be obtained as noted above. In some cases the oblique light findings and the electrostatic findings may complement one another with some details better revealed by one process and other details by the second process. Which details are best revealed by which process also needs to be recorded.

9.4 Reports in indented impressions cases

Reporting cases involving indented impressions of handwriting are generally straightforward since they require just a description of the details deciphered. The main issue is to make sure that any uncertainties about specific elements of the deciphering are clearly indicated (see also Section 9.1.5). If a piece of equipment is used to visualise the impressions then this needs to be mentioned in the report, but it is not normally necessary to describe how the machine works.

If the evidence is particularly difficult to decipher, it may be worth considering scanning any visualised impressions and including these images in the report to assist the reader in interpreting the findings.

Figure 9.3 Worked example: Electrostatic trace from the hold up note.

References

- Barr, K. J., Pearse, M. L., & Welch, J. R. (1996). Secondary impressions of writing and ESDA-detectable paper-paper friction. Science & Justice, 36(2), 97–100. doi:10.1016/S1355-0306(96)72573-X.

- D'Andrea, F., Mazzella, W. D., Khanmy, A., & Margot, P. (1996). The effects of the relative humidity and temperature on the efficiency of the ESDA process, International Journal of Forensic Document Examiners, 2(3), 209–213.

- Daéid, N., Hayes, K., & Allen, M. (2008). Investigations into factors affecting the cascade developer used in ESDA—A review. Forensic Science International, 181(1–3), 1–9. doi:DOI: 10.1016/j.forsciint.2008.09.003.

- Radley, R. W. (1993). Determination of sequence of writing impressions and ball pen inkstrokes using the esda technique. Journal of the Forensic Science Society, 33(2), 69–72. doi:10.1016/S0015-7368(93)72983-7.