THE GREAT DRAMA

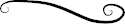

ALICE AND FREDA MET at the Higbee School for Young Ladies, where well-to-do white Memphians sent their daughters. Together, they roamed the hallways with Freda’s older sister, Jo, and Alice’s bestfriend, Lillie. The foursome was well known, as was their coupling. Alice and Freda had made no attempt to hide their relationship: their kissing and hugging and hand-holding was certainly noted by those around them. But Jo and Lillie were also seen with their arms linked, sharing meaningful glances and speaking in hushed voices.

During the Victorian era, proper American women were not to speak of their desire for men, let alone show it, but demonstrative relationships with other women were considered unremarkable. In Memphis, “chumming” was the regional term for intimate female friendships, but it was by no means particular to Eastern Tennessee. The poet Henry Wadsworth Longfellow called these romantic friendships a “rehearsal in girlhood of the great drama of woman’s life,” a kind of training ground for the main event, the courtship by a young woman’s future husband.4

But for Alice, this was no rehearsal.

In Europe, sexologists were just beginning to define same-sex love, but this nascent research had barely reached American soil; the word lesbian would not be in circulation for another forty years. In the South, a white woman from a respectable family was bombarded with a consistent message at home, school, and church: She was expected to play the role of wife, and then the role of mother to as many children as her husband desired. A couple like Alice and Freda had no name for what they felt for each other, no adults to advise or serve as examples, and certainly no literature to call upon.

They went to the theater often enough to know that actresses could play male roles convincingly, but that was likely the furthest either of them saw gender boundaries pushed—and even then, this deviance was safely contained within the realm of playacting, much like the notion of chumming itself. Once the curtain came crashing down and the house lights blinded the audience, the rules of society were reinstated. The actresses discarded men’s costumes in favor of their own dresses, as if to acknowledge their male characters belonged within a very small and specific space, for a limited time only.

American newspapers would later speculate that French fiction, full of risqué tales of same-sex love and other noteworthy acts by libertines, had possibly influenced Freda’s murder. But even if English translations of books by novelists Honoré de Balzac, George Sand, or Théophile Gautier made it to Memphis, it was unlikely that Alice would have happened upon them.

If Alice had indeed read those French novels, she might have realized that other women shared her desires. She seemed to feel trapped by emotions she understood to be unique, and may have taken some comfort in the idea that there were other women in the world to love and, more importantly, who would love her back.

But would French novels have really made a difference, either way? Alice’s obsession with Freda was so great, so all encompassing, that any tale of alternate domesticity was unlikely to alter their tragic ending—even if the tale was their own.5

FREDA WAS FAR MORE CAPRICIOUS with her affections, as Alice would soon realize, but in 1891, their greatest challenge was geographical. Freda’s eldest sister, Mrs. Ada Volkmar, had moved to Golddust, a small town on the Mississippi River, and their father, the widower Thomas Ward, soon followed. He relied on Ada to look after Freda and Jo, but the new city offered him more than just help with his younger daughters. Back in Memphis, Thomas had been a machinist at a fertilizer company, but in Golddust, he was able to work as a merchant and a planter. Things were looking up for the Ward family.

Alice and Freda had no choice but to make the best of it. They no longer lived in the same city, but when they visited each other, they did so for weeks at a time. Every day was spent together, every moment precious.

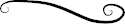

The nights were advantageous, too. After they kissed their families goodnight, it was expected that they would share a bed, their bodies close, their movements obscured under the covers.

Long visits spent in such close proximity had a downside, too. It became harder for Freda to hide her infidelities from Alice, and even harder still to escape her anger over them.

Late one night in December, the Mitchell home was still. The entire family, with the exception of Alice, was fast asleep. She lay in bed, alongside Freda, wide awake. In her hand, she clutched a bottle marked POISON.

Before falling asleep, Freda had admitted to loving not one, but two men. The sun would rise soon enough, ushering in the day Freda would return to Golddust, where she would once again move freely, far from Alice’s watchful gaze. As the hours passed, Alice concluded that either she or Freda would have to die. Laudanum, a potent mix of opium and alcohol, was easy to procure for various aches and pains, but it came with a warning. The solution was highly concentrated, and fatal overdoses were not uncommon. If Alice could get enough past Freda’s lips while her beloved slept, the drink would likely be her last.

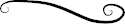

Alice would eventually write out a more comprehensive list—“How to Kill”—but that night laudanum was her only option, and she could hardly guarantee there was enough for both of them. And so she lay there, inches from her love, contemplating how many doses she held in her hand.

And that was the scene that greeted Freda when her eyes fluttered open. She was sharing a bed with a young woman who was deciding whether or not to kill her. The night was fraught, with Alice openly brandishing the bottle, and Freda too scared to close her eyes—and yet, Freda stayed in that bed with Alice. She never called for help, and she never told the Mitchells, or her own family, what had happened.

Daybreak did nothing to quell the drama. Laudanum in hand, Alice followed Freda onboard the steamer that would soon leave for Golddust, cornered her in the stateroom, and locked the door behind them.

“Marry whomever you want,” she said, and downed the bottle herself.

DIE, ALICE DID NOT, but the aftermath could not have been pretty. A laudanum overdose did not guarantee death, but symptoms like insufferably itchy skin, constricted breathing, and obstructed bowels may have made her wish it had.

If nothing else, it was clear that Alice needed a better plan, one that took control of the situation. If things continued this way, Freda would be married soon enough. She might settle in Golddust, near her family, or worse yet, move to where her husband’s people lived. Alice needed to find a way to possess her love completely, to make her ineligible to all bachelors.

Alice’s own future would soon come into question as well. Whether she liked it or not, the cult of domesticity was the prevailing value system in the United States and Britain, and it identified the home as the proper sphere for women of Alice’s race and class. She had certainly been told this at Miss Higbee’s. The first page of the school’s catalog stated its educational aim quite clearly: “The Systematic Development of True Womanhood.”6 The four cardinal virtues—piety, purity, submissiveness, and domesticity—were not only taught in schools, but reinforced by magazines, cookbooks, newspapers, literature, and in church every Sunday.7

Alice was adept at discouraging suitors, but that would be difficult to maintain, especially if her family forced the issue. If she relented to pressure and married, there would be babies, one after the other, both her own or those of her siblings. She would be expected to help maintain the household, with little-to-no autonomy or authority over anything, including her own body.

If she did not marry, her father and brothers would decide her fate. The options in that scenario were clear: Alice could continue to live in her parents’ home, as her older sisters had, or with her married siblings.

Alice seemed to want out of the Mitchell home and into her own, but it was not as if she could just go out and get an apartment, or the job she would need to pay for it. Occupations for women were extremely limited in the 1890s, especially for her class. Of the 8,200 women employed in Memphis in 1891, 2,200 were white, and the majority of these wage earners were servants and seamstresses, and they still ended up in someone else’s home, whether it was their family’s, their employer’s, or a boarding house. They were rarely from well-to-do families like the Mitchells, working out of necessity, and yet, only about three percent made enough to claim economic independence.8

One way or another, a man would be the head of Alice’s home, and she would live the kind of life he saw fit. The other Mitchell women seemed perfectly happy to spend day after day inside, with women like Lucy Franklin tending to the household’s daily demands. Their hours were spent in a state of perpetual anticipation, filled with leisurely activities like mending and knitting, writing letters, and reading the Bible. Whether they enjoyed these tasks, or regarded them as mere distractions was immaterial; everything depended on the Mitchell men. Any time Alice’s father and brothers came in the front door, their needs were prioritized above all else.

The kind of power Alice craved, the right to come and go as she pleased and, most importantly, fully dominate Freda, could only be wielded by a man.

And so Alice would have to figure out a way to become one.