THAT STORY WAS NEVER PRINTED

DECLARED INCURABLE BY LEADING medical experts and judged to be insane by a jury of the finest men in Memphis, Alice was remanded to the Western Hospital for the Insane in Bolivar, Tennessee.

She was to be committed on August 1, 1892. After six months of being a public figure—the subject of endless lurid speculation across the country— Alice was gone, out of sight in nearby Bolivar. The Wards silently accepted that justice would not be served, and returned home to Golddust. The big urban dailies called their reporters home, and the emptied city moved on.

WHEN ALICE ARRIVED IN BOLIVAR, the insane asylum was only in its third year of operation and already overcrowded. The third of its kind in Tennessee, the asylum was built to accommodate some 300 patients, divided by race and gender. But Alice’s arrival pushed the asylum’s population to 319, a number that would continue to rise. The luckiest among the 151 males and 168 females retained at least some semblance of privacy, but when patients began to number in the thousands, they were crowded into large dormitories.

Alice joined Bolivar’s largest patient population, the 37 percent who had a “hereditary predisposition.” This was followed closely by alcoholism and epilepsy in men, and for women, uterine trouble, those who suffered by the vaguely defined “ill health,” and even the flu.

The only recorded therapy Alice received was “moral treatment.” It should have entailed regular exercise, a healthy diet, some kind of work or hobbies to occupy the fragile mind, and occasional amusements, like dances, concerts, and magic lantern shows. Men farmed and went to workshops, while women did laundry and spent their days in the sewing room.127

But patients during this time period often received harsh treatment, and there was little oversight. The asylum staff was overworked, and they were easily frustrated when patients receiving ineffectual treatment failed to progress.

Not that there was ever any expectation that Alice would “recover.” The asylum was run and staffed by doctors who had declined the prosecution’s requests to testify at the lunacy inquisition. There was no need to interview Alice, they had said, as the sensational news stories had already convinced them of her insanity. The year she was admitted, the asylum’s own publication, the Bolivar Bulletin, reported that experts believed “her insanity is progressive, and it is only a question of time when this victim of erratic [sic] mania will be a driveling idiot through the decay of brain tissue.”128

Of course, the efforts of George Mitchell could never be underestimated. He had, by that time, already proven to be highly effective at getting women in his family institutionalized. Alice had made the Mitchell family front page news, and it was easier to move on with her out of sight. Should the doctors ever consider releasing Alice, the Attorney General would have the option of reopening the case, but it seems unlikely George would have allowed that to happen.129

ALICE, WHETHER BY HER OWN VOLITION OR NOT, gave few interviews in the years that followed. When she did, the questions posed were curiously devoid of any reference to Freda, the murder, the inquisition, or her mental state. In a dubious article from March, 1893, Alice was described as a “bright, happy, laughing girl” who nonchalantly referred to the “tragedy that ruined her life.”

These articles sought to reverse the public’s conception of Alice as a perverted, masculine murderess. She now lived “in a pretty little room,” which she kept neat before dashing off to spend her days doing the kinds of feminine activities she had allegedly shunned her entire life. At Bolivar, she was said to love needlework, embroidery, and even reading—despite the fact that the Hypothetical Case had asserted she had shown “no taste for books or newspapers, and reads neither the one nor the other.” She suddenly played the guitar, even though “efforts to teach her music and drawing were a failure” for the first nineteen years of her life.

The least believable claim of all: “The dances and concerts in the amusement hall were dull and spiritless without Alice Mitchell’s presence. She dances well and never misses a set.”130

Of course, if any of that were true, it would suggest that Alice was indeed on her way to “recovery,” if not already capable of standing trial for murder—but that was not the goal of these articles. They assured the public that Alice was now tame and docile, and everyone was safe: she from herself, and from harming others. It comforted readers to see that Alice, at the end of the day, posed no serious threat to their values, or their class. She was now happy and feminine, vindicating their way of life. And if Alice was really the good, well-bred lady she was raised to be all along, the storm had passed.

Even the record itself hints that this public narrative of Alice was, as usual, not quite accurate. The Bolivar Bulletin, for example, concurred that Alice attended every dance, but did not specify whether or not they were mandatory. And their description of her refusal to dance with anyone other than male asylum attendants strongly suggests that the dances were indeed mandatory, and belies the image of her bringing jollity and high spirits to the amusement hall.

“No, I don’t care to dance or have anything to do with Bolivar boys,” she is reported to have said, “for I know they want to meet me merely for curiosity.”131

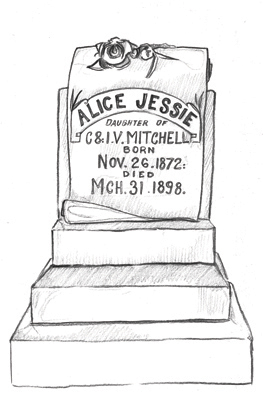

ON THE LAST DAY OF MARCH, 1898, Alice Mitchell died. She was twenty-five years old.132 There was no cause of death listed on the patient rolls, but the local papers declared her the victim of consumption. Alice appeared to be faring well, at least physically, until about 1897, when her health suddenly waned. She was described as “wasting away.” Her body “gradually failed until the end came as it usually does to the insane— a collapse of the whole system.”133

In Alice’s case, consumption may have meant that she starved herself, which she had previously considered, or it could have meant tuberculosis, which was certainly on the rise at the asylum. Of the sixty-nine deaths from 1896 to 1898, twenty-three resulted from the respiratory disease referred to at the time as “phthisis pulmonalist.”134

Alice’s unexpected demise from tuberculosis could be easily reconciled with the account of her “happiness” at the asylum—but there is another possible explanation.

Thirty-two years after Alice died, Malcolm Rice Patterson made a startling admission. He told the Commercial Appeal, “Those closest to the case knew . . . she had taken her own life by jumping into a water tank on top of the building. But that story was never printed.”135 By his own description, Patterson would have been privy to this kind of information; he had represented Lillie Johnson in the trial, and had been employed by the same law firm that represented Alice, often supporting the defense’s case and appearing alongside them in court.

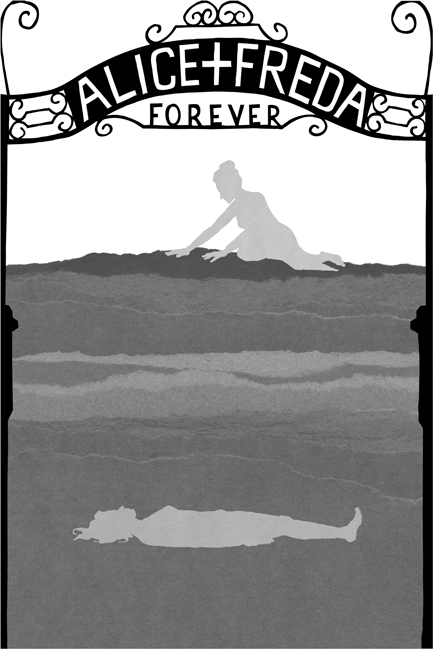

Like much about her life, the story of Alice’s death may have been a projection of the people around her, driven by fear and shaped by what they wanted to be true. We do not know exactly how Alice Mitchell died. We might never know. But we do know that it reunited her—almost—with her beloved: Alice and Freda were both buried at Elmwood Cemetery, about a quarter of a mile from each other. Because the Mitchells were of comfortable means, Alice was buried in a family plot, and her ornate headstone still stands; Freda’s was unmarked until recently, when a tree was planted on the site.

ON HER WAY TO THE INSANE ASYLUM IN 1892, Alice made one last request.

During the inquisition, the Mitchell family had insisted that Alice, in her insanity, believed Freda was still alive, but if her own testimony on the stand had not convinced the public otherwise, her final stop should have: Before being committed, Alice wanted to visit Freda’s grave at Elmwood Cemetery.

Freda had no headstone, nor marker of any kind. Whether it had been a gesture of sympathy or much needed aid, Freda had been buried in a plot owned by the very same church she and Alice had hoped to be wed in. When Alice arrived at Elmwood on that August day, a year after they were forbidden to speak, she was trailed by reporters.

But even without a marker, Alice found Freda’s plot, a mound of dirt that had settled while she was in jail. The spring had brought grass, and the summer wildflowers. At night, fireflies flew low, illuminating the ground.

What did Alice say to Freda? What was she thinking about? Was it the first time she saw Freda at Miss Higbee’s? Did she imagine what their life would have been like, had they made it to St. Louis? Maybe she felt a jolt, like when a letter arrived from Freda, or when she picked the perfect rose for her beloved. Or maybe she thought about that photograph of her beautiful Freda, the one Alice had said she would not part with, even after they were forbidden to ever speak again.

But in the end, that photograph had been taken from her, along with the engagement ring she had engraved “From A. to F.,” and all of the other treasures she kept hidden in her family’s kitchen. It was all gone now.

We will never know what Alice was thinking at Elmwood that day, and neither did the journalists who watched from afar. But they did report what they saw, and, for once, what they wrote seems believable: Alice dropped to her knees and, for the woman she loved without shame, wept openly.