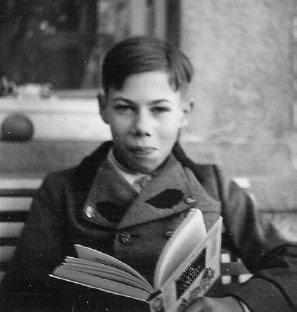

The young Wolfram, here in 1934 aged 10, spent all his spare time drawing and painting. During the Third Reich, he tried to avoid the Hitler Youth in order that he could pursue his passion for art.

Wolfram’s father, Erwin, in the garden of the family’s magnificent villa. He was a celebrated wildlife artist and he kept a large menagerie of animals.

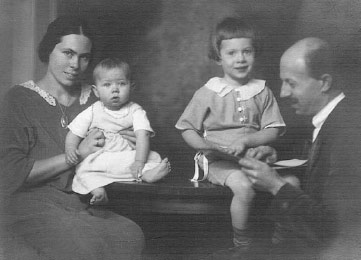

The Aïchele family circa 1925. Marie Charlotte, Wolfram, Reiner and Erwin. Wolfram’s sister, Gunhild, was not yet born. The years before the Third Reich were happy, despite economic hardship.

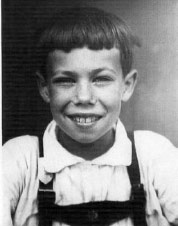

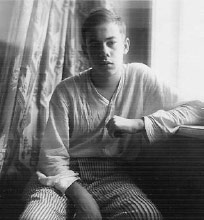

Wolfram, aged 11. He was a curious young lad with a passion for Gothic art and medieval sculptures.

Wolfram and his brother, Reiner, built a miniature medieval hamlet in the lower garden. Each cottage was about three feet high; the accuracy of the construction astonished adult visitors.

The young Wolfram had a lively sense of humour. He would later amuse his comrades – and unknowingly risk severe punishment – with his impersonations of a ranting Hitler.

Wolfram loved to sketch the medieval villages of his native Baden. This drawing was published when he was just 11 years old.

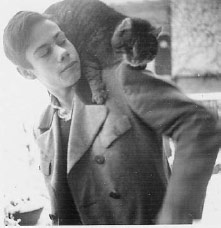

Wolfram loved to play with his father’s animals. Here he is, aged 15, with Peter the cat.

Marie Charlotte with Hansi and Thora.

Erwin produced animal sketches for a hunting magazine. It was banned by the Nazis because the owner was Jewish.

When local farmers found injured animals in their fields, such as this deer, they brought them to Erwin because they knew he would look after them.

The family’s Italianate villa in Eutingen was very different from most houses in rural Swabia. The Aïcheles’ private world, it was an island of culture that remained isolated from the worst realities of the Third Reich.

Reiner, Gunhild, Erwin and Marie Charlotte in the dining room. The house in Eutingen was filled with beautiful furniture.

Pforzheim’s reformed synagogue was the principal meeting place for the town’s large Jewish population. It was attacked and seriously damaged in November 1938.

The Marktplatz (or market square) in central Pforzheim. It was here, in 1933, that the town’s Nazi authorities staged a public burning of books deemed un-German.

Wolfram’s wood-sculpting tutor in Oberammergau, Johann Georg Lang. Wolfram became good friends with Lang’s nephew, Werner, when they served together in a communications team in Normandy.

Wolfram, on the right of the picture, greatly enjoyed his time in Oberammergau. He was infuriated when he was conscripted into the Reich Labour Service.

The studio in Oberammergau. Wolfram excelled at his studies and was one of the best students in his year. He returned there after the war; it was the beginning of a lifetime’s creativity.

A youthful Peter Rodi says farewell to his sister, Ev-Marie, as he begins his obligatory service in the heimatflak, or home defence, the first inevitable step towards military conscription.

Wolfram on leave in February 1944, his final holiday before invasionstag (or D-Day). It was the last time his parents saw him for more than two years.

Adolf Hitler visits Pforzheim and Eutingen, en route to the fire-damaged village of Öschelbronn, in September 1933. The Aïchele family were criticised by neighbours for declining to join the cheering crowds.

The Nazi leader of Baden, Robert Wagner, inspects a rally in the market square of Pforzheim, November 1934. Wagner was one of the most fanatical regional leaders.

Election poster, 1932. Women were instructed to vote for Hitler. Wolfram saw posters like this all over Pforzheim.

Poster celebrating the League of German Girls – the female branch of the Hitler Youth. Girls went from door to door collecting money, in this case for ‘youth hostels and homes.’

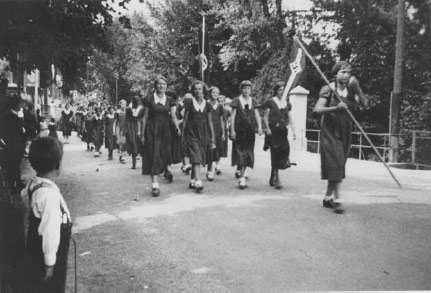

A 1933 street march of the League of German Girls in Hornburg, near Pforzheim.

Uniformed officers confiscate books in preparation for burning them. The above took place in Hamburg: similar scenes occurred in Pforzheim in June, 1933.

Nazi policy was to deport all Jews in Germany (left). Among the first communities to be deported was that of Pforzheim in October 1940.

State sponsored anti-Semitism was ubiquitous: here, one of Pforzheim’s Jewish owned shops, Ehape, is guarded by uniformed Nazis. ‘Scoundrel’ reads the banner outside.

Hitler held inflexible views about art. National Socialist art (right) was championed by the state, while ‘degenerate’ art (above) was displayed for public ridicule at the infamous Munich exhibition, 1937. The caption reads: ‘German peasants viewed through Yiddish eyes.’

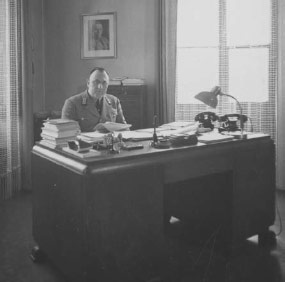

Hans Knab was the local Nazi leader in Pforzheim – the eyes and ears of the regime. Gestapo officers and informers helped him monitor all aspects of life in the town.

Sebastopol, above, was seriously damaged during its capture by German forces. In 1942, Wolfram saw similar scenes of destruction in Kerch, at the eastern end of the Crimean peninsula.

Wolfram recuperating in a military hospital in Marienbad, 1943. As soon as he was better he was sent to Normandy, arriving in time for the D-Day landings.

Wolfram served as a ‘funker’, or wireless operator, working in a small team similar to the one pictured. It was dangerous front-line work as wireless operators were specifically targeted by Allied forces.

‘Schnell! Quick! Take cover!’ On 17 June, 1944, Wolfram and his comrades were attacked from the air. Wolfram was one of the lucky few to survive.

Wolfram and his comrades gratefully surrendered to American forces. They were taken to a makeshift encampment, similar to above, adjacent to Utah Beach.

German prisoners of war were transported from New York to their prison camps in Pullman trains.

German prisoners painting the letters PW onto their uniforms. The American uniforms were of a far superior quality to the German ones.

Wolfram and his fellow prisoners were obliged to watch a film showing Allied forces liberating an extermination camp. They were deeply shaken by what they saw.

Pforzheim, 1945. The historic town centre was obliterated by RAF incendiary bombs on the evening of 23 February. Among the 17,000 dead were many acquaintances of the Aïcheles.

Wolfram returned to his studies in Oberammergau in 1946. His sculpture of Christ on a donkey was carved for the parish church of St Peter and St Paul. It remains there to this day.