Chapter 11

But Freddy didn’t go home that night. He had no wish to be pulled out of his comfortable bed in the pigpen in the middle of the night by an enraged Mr. Flint, and maybe shot full of large round holes. So he rode around the end of the lake to Mr. Camphor’s house. He rode up to the front door and rang the bell.

Bannister answered. Bannister was Mr. Camphor’s butler, a very tall man in a tail coat with a very high bridge to his nose which he held so high in the air that unless you were an important personage, he could almost never see you over it. Freddy, however, was pretty high up in the air, too, being on horseback, so after Bannister had said: “Sorry, sir, Mr. C. Jimson Camphor is not at home,” he caught sight of the pig. “My word,” he said, “it is Mr. Frederick! Happy to see you, sir.”

“Thank you, Bannister,” said Freddy. He pointed to two mice who were peeking out of his pockets. “You remember Cousin Augustus. And this is my friend, Howard. And this pony is another new friend, Cy.”

“Happy to see you, gentlemen,” said Bannister. “Mr. Camphor is in Washington. He will be sorry to have missed you. But come in, come in. Your room is always kept ready for you, you know, Mr. Frederick. And we can put these two gentlemen in the blue room, I think. As for Mr. Cy—” he looked doubtfully at the horse.

“Cy’s a Western pony—never sleeps indoors,” said Freddy.

“We’d rather sleep in the kitchen if it’s all right,” said Cousin Augustus, and Howard said: “We don’t feel at home in bedrooms. No crumbs usually.”

“Dear me,” said Bannister, “two mice with but a single thought.” Then he looked startled. “Ha!” he said. “Ha, ha! I seem to have made a joke!”

Cousin Augustus was offended. “Yeah?” he said. “Well, it doesn’t seem very funny to me.”

“He’s not making fun of you, mouse,” said Freddy. “It’s just a quotation he’s twisted around. It’s two minds with but a single thought, you know.”

“No offense meant,” said Bannister.

“O.K.,” said Cousin Augustus grumpily, for he was still a little seasick from the ride. “O.K., O.K., O.K.. Well, let him mind his manners and not go throwing his quotations at me.”

So they spent a quiet night at Mr. Camphor’s, and in the morning they held a council of war, with Bannister’s help. There was a good deal of arguing, particularly between Bannister and Cousin Augustus, who still seemed to hold a slight grudge against the butler. But at last a plan was decided on.

That afternoon they paddled across the lake—all but Cy who refused (and I think, on the whole, sensibly) to get into the canoe—and had a picnic at their old camp site on the north shore. And the following morning Bannister drove them into Centerboro, where Freddy bought a number of things. He bought a false moustache and a wig with long hair, that made him look like pictures of General Custer. He bought a green shirt with a design of yellow pistols on it, and a new gun belt studded with what looked like diamonds but probably weren’t; and he bought a great many packages of red Easter egg tint. After that they spent nearly a whole day tinting Cy, and turning him from a buckskin into a roan.

Both Cy and Bannister agreed that the plan that Freddy had finally adopted was a very dangerous one, because its success depended on how good his disguise was. And as a rule Freddy’s disguises were interesting, but not very convincing. If his moustache fell off, or if his wig slipped sideways, he was sure to be recognized. And if he was recognized, he ran a very good chance of being shot at. But Freddy was determined. He was really quite a courageous pig. I don’t mean that he wasn’t scared; he was so scared thinking about it sometimes that his teeth chattered and his tail came completely uncurled. But he didn’t propose to let being scared interfere with what he intended to do.

And so, after all his preparations were made, on the day of Mr. Flint’s rodeo he saddled Cy and they started for the ranch.

Now a good disguise isn’t just something you put on, like false whiskers, or a funny hat. You have to take all the little things that people might recognize you by, and change them. And one of the most important of these is the way you walk. For people can recognize you by your walk long before they get close enough to see your face. So Freddy, who ordinarily sat up pretty straight, slouched in the saddle and held his head on one side, and Cy trotted along with a quick little jerky step that was quite unlike his usual gait. From a distance they certainly wouldn’t look familiar to Mr. Flint. And when they got closer, Cy’s color, and Freddy’s long drooping moustache and lank black hair hanging down over his collar, would throw him completely off the track.

Mr. Flint’s rodeo was of course a small one, but he had brought along a few animals for the steer-wrestling and calf-roping events, and a few horses that would buck mildly when teased. The prize money he was offering wasn’t large, but several riders who had been making the rounds of the eastern rodeos dropped in to try to pick up a little of it. Some bleachers had been knocked together and when Freddy got there there was a good-sized crowd filling the bleachers and strung out along the fence surrounding the arena. A lot of his friends from Centerboro were there. He saw Judge Willey and the sheriff, and Mr. Weezer and old Mrs. Peppercorn.

Freddy rode up to the gate through which the contestants entered just as the calf-roping was over. Mr. Flint had won with a time of twenty seconds, and the audience applauded him as he came out. He stopped as he caught sight of Freddy. I guess you can’t blame him, for Freddy, though small, was a pretty tough-looking specimen as he sat there pulling at his long black moustache. He didn’t of course pull it very hard, for it was only fastened on with mucilage. One of the dudes, who was familiar with the pictures of the old-time Western bad men, said that he looked like Wild Bill Hickok, seen through the wrong end of a telescope.

“Howdy, mister.” Freddy made his voice as hoarse and rough as he could. “You the boss here?”

“That’s right,” said Mr. Flint. “You want to get in the show?” Suddenly he turned away from Freddy, to look towards Jasper who had set up a target on one of the corral posts, and was about to give an exhibition of knife throwing. “Jasper,” he called, “lay off that till I get around back of the pen.”

“I forgot, boss,” said Jasper. “Can’t stop now; you look the other way.” And he pulled out a sheath knife and balanced it on his palm.

Freddy started to say something and then stopped, for Mr. Flint seemed to have been taken suddenly sick. He reached up and took hold of Freddy’s saddle horn and supported himself by it as he leaned against Cy. Big drops of sweat ran off his forehead and he shut his eyes and began to tremble. Cy looked around and raised his eyebrows inquiringly, but Freddy shook his head at him warningly. It was a nice chance to take a good bite out of Mr. Flint, but it would spoil their plan.

Jasper held the knife flat, on his open hand, point towards him; then tossed it underhand with a flip, and it turned over twice in the air and went plunk! into the center of the target. And Mr. Flint jerked as if it had gone into him.

“You shore look sick, mister,” said Freddy. “Likely you ought to get in the bunkhouse.”

Plunk! went another knife, and Mr. Flint jerked again and moaned faintly, and then Jasper came running over to them. “Get him out of here,” he said disgustedly, “I’ve got to finish this now I’ve started it. He can’t stand knives—makes him sick to see ’em. I guess he cut his finger when he was a little boy or somethin’. Hey, you—Slim!” he called to another puncher, “Get the boss out of here.”

Slim came over and said: “Come on, boss,” rather contemptuously, and then he hooked Mr. Flint’s arm over his shoulder and led him around behind the bleachers.

Freddy watched the knife throwing. Jasper was good. He threw mostly underhand and could make the knife turn over one, two or three times before it hit the target. His final stunt was to throw at a can tossed in the air. He pierced it on the third try.

Freddy waited around. He watched some fancy riding, and after a while Mr. Flint came back. He looked all right.

“Must have et something that disagreed with me,” he said. “Now, was you aimin’ to get into the show? Good chance to make a little prize money, if you can beat the time of some of these other boys.”

Freddy shook his head. “Your money don’t interest me none, pardner. Maybe you heard of me; I’m Snake Peters. Come from Buzzard’s Gulch, Wyoming. I been sort of sashayin’ round mongst these rodeos, tryin’ to find somebody could stay on this little horse of mine more’n thirty seconds. You got any good riders?”

“He don’t look very tough,” Mr. Flint said. Cy certainly didn’t. He stood awkwardly with his front feet crossed, and everything about him drooped—his tail, his eyelids, his head; and his mouth was open. He looked worn out and sort of half-witted, if there is such a thing as a half-witted horse. Mr. Flint went up and stroked his neck, then he poked him in the ribs. Cy didn’t move.

Mr. Flint shook his head, “We can’t use horses like that in our show, friend. Even if you put up money for any rider that could stay on him. We got to give the customers some excitement, and there ain’t enough excitement in that animal to put in a bug’s ear.”

“I’ve got five dollars for anybody can stay on him thirty seconds,” said Freddy.

“Move along, move along,” said Mr. Flint irritably. “And take that hunk of crowbait away from here. Go on; beat it.”

A number of the onlookers had edged up to listen, and among them was Bannister, who now pushed forward. “I say, hold on a minute,” “I’ll ride this creature for five dollars. I have never ridden a horse, but if someone will help me up into the saddle I am sure I can stay on thirty seconds.”

Mr. Flint started to object, but some of the crowd had begun to laugh, and he hesitated. “Well, O.K.,” he said. “We need a good clown act. Get down you, Peters; and Jasper, get that megaphone and give ’em an announcement.”

So Jasper went out in front of the bleachers. “Ladies and gentlemen,” he said, “Mr. Snake Peters, the gentleman with the wind-blown bob and the soup strainers, has offered five dollars to anyone who can stay on this here wall-eyed roan horse of his for thirty seconds. His offer has been took up by the gentleman in the claw-hammer coat. This gentleman—what’s your name? Bannister?—this Mr. Bannister claims he’s never rode anything livelier than a wooden horse on a merry-go-round, but in spite of the way Mr. Peters’ horse is a-rarin’ and snortin’ fire, he’s going to try for the five dollars.”

The bleachers laughed and applauded, and Mr. Flint hoisted Bannister into the saddle, and shoved Cy through the gate. It certainly wasn’t much of a show. Cy walked slowly up to the fence, leaned against a post, dropped his head and went to sleep. When Mr. Flint called, “Time!” he woke up, walked back, and Bannister was helped down.

Freddy handed over the five dollars. Then he grabbed the megaphone and before Mr. Flint could stop him, he addressed the crowd. “Ladies and gentlemen, I am now offering Mr. Flint himself fifty dollars if he can stay on my horse thirty seconds.” Then, remembering that he was supposed to be a wild and wooly Westerner, he continued: “This here horse, gents and ladies, has got a kind nature. He knowed that this Bannister wasn’t a fair match for him, and he let him off easy. But Cal Flint here, he’s good, he’s—”

“Oh, dry up and get out of the arena,” Mr. Flint interrupted. But there were shouts from the bleachers: “Go on, Cal. See if you can wake the old nag up. Ride him, cowboy!” He turned to Freddy. “Let’s see the color of your money.”

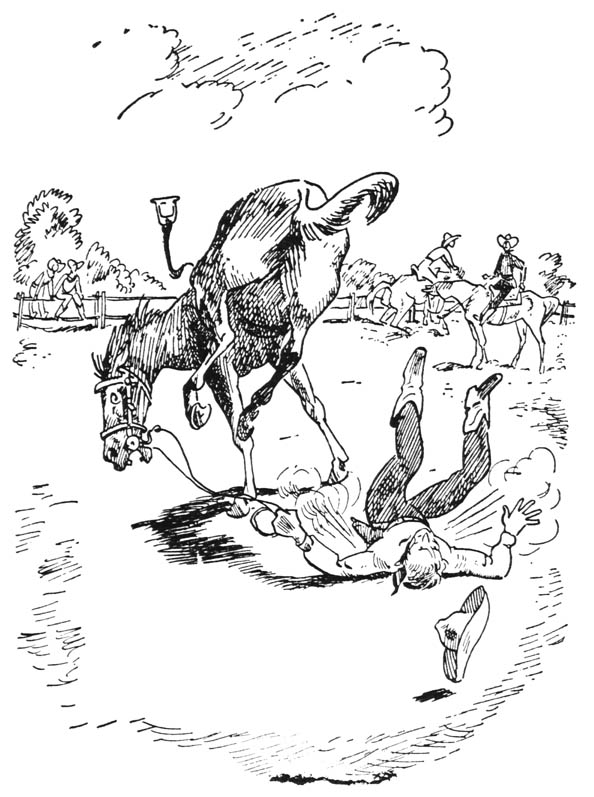

So Freddy pulled out some bills. Mr. Flint looked at them, then swung into Cy’s saddle. Jasper held the watch, and when he yelled, “Time!” Mr. Flint jabbed his spurs in and whacked Cy with his hat. But Cy didn’t start anything. He just ambled off around the arena, and when Mr. Flint realized that he looked rather foolish yelling and jumping around on such a quiet animal, he relaxed and sat easily in the saddle, dropping the reins and folding his arms. It was then—at the twentieth second—that Cy stumbled. His forefeet stumbled, and at the same time his hindquarters twisted sideways. And Mr. Flint somersaulted right over his shoulder.

His hindquarters twisted sideways.

He was up in an instant. He paid no attention to the crowd which was staring open-mouthed, but ran after Cy who had trotted back to the gate. “Hey!” he shouted to Freddy. “That wasn’t fair—it was an accident! It was a trick! I demand another trial.” He grabbed Cy’s bridle.

“You’re a poor sport, Flint,” said Snake Peters, smoothing his long moustache. “You had your trial. You ain’t earned your money. ’Tisn’t my fault if you can’t ride a horse without being tied to the saddle. Stand away from that pony.” He dropped his right hand to the butt of his gun.

Freddy was sure that Mr. Flint would not care to put himself in the wrong with the crowd by shooting, and he was right. The man took his hand from the bridle. “That was a trick,” he said angrily. “I don’t want your money. But I ain’t going to have it said that Cal Flint can’t ride a half-dead old plug that ought to be shipped off to the boneyard.”

“I don’t want your money either,” said Freddy. “But you ain’t going to get another trial free.” He started to spit out of the side of his mouth to make himself more like Snake Peters than ever, but decided against it on account of the moustache. “Lemme see, those are nice guns you got there. You stay on this horse thirty seconds and you get fifty dollars, but if he throws you, I get the guns. Is it a deal?”

“If I can’t stay on that camel I’ll shoot myself with those guns,” said Mr. Flint. “Sure it’s a deal. Keep the time, Jasper.” A second later he was astride Cy.

When Mr. Flint got into the saddle, Cy woke up. He woke up so violently that it was as if he had suddenly exploded. He bucked and whirled, reared up and twisted and put his head down and almost stood on his forelegs. Mr. Flint’s arms and legs flew in all directions and his head snapped back and forth until it looked as if it would fly off. He lasted seven seconds. Then he catapulted through the air and smacked flat on his face on the ground, and Cy picked him up in his teeth by the seat of his pants and tossed him over the fence.

The crowd in the bleachers yelled and waved and were so excited that several of them fell between the benches and had to be dragged out from below. Mr. Flint sat up slowly, shook his head several times, then got to his feet.

Freddy came up to him. “I’ll take those guns, Flint,” he said.

Mr. Flint glared at him viciously. He pulled out the guns, and for a minute Freddy thought that he was a gone pig. But Jasper had hold of Mr. Flint’s arm. “Easy, boss,” he said. “Don’t let the crowd get sore on you.” And he took the guns from him. Then he turned to the bleachers. “Mr. Flint wants me to say,” he called, “that he’s paying up because he lost the bout, according to the terms as they was arranged. But he also wants me to say that what you have just seen here is not a straightforward performance. This horse is not the usual wild horse used in such trials. He’s a trick horse, trained to throw you off your guard and then cut loose on you. He wants me to say—”

The crowd began to jeer. “Yah! He lost, didn’t he? Why don’t he shut up?”

Freddy had got into the saddle, and he now rode up towards the bleachers. So far everything had gone as he had hoped. He had disarmed Mr. Flint; now, in front of all the people, dudes from the ranch and neighbors from Centerboro and the surrounding farms, he planned to stand up and tell his story. He was going to take off his disguise and then, holding the guns on Flint to keep him from interfering, he was going to tell of Mr. Flint’s cruelty to Cy, of his plan to rob the Animal Bank, and of his threat to shoot him, Freddy, on sight. For he believed that to get his story before the public was the only way to protect himself from being killed. The anger of the whole community, Freddy thought, turned against Mr. Flint, would make him behave himself.

Now this was not a bad plan. If nobody knew about his threat, Mr. Flint could shoot Freddy and pretend that it was an accident. But if everybody knew about it, he couldn’t make the accident story stick. Everybody would be pretty mad at Mr. Flint, for Freddy was a popular pig, not only among the animals, but among the Centerboro people.

Unfortunately, just as Jasper turned to hand the guns to Freddy, a little gust of wind came along. It swirled around Freddy, lifted the brim of his hat, twisted his moustache, lifted the long hair of the wig that hung over his shoulders. Mr. Flint was looking at him, and suddenly he recognized him. He gave a yell and grabbed the guns back from Jasper. “The pig!” he shouted. “Draw, pig, defend yourself!”

This time Freddy just about gave up hope. The guns were within a foot of his stomach, and he could feel his stomach trying to sneak around and hide behind his backbone. Jasper said: “Hey! Hey, boss; don’t do it!” But Freddy could see that nothing was going to stop Mr. Flint this time. Bannister had come through the gate and was trying to get round behind Mr. Flint, but Freddy knew that he would be too late.

And then Howard climbed up out of Freddy’s pocket and did one of the bravest deeds ever done by any mouse in the history of the world. He jumped to one of the pistol barrels, ran up the arm to the shoulder, and dove right down the open collar of Mr. Flint’s shirt.

Mr. Flint gave a yell and threw up his arms, and then as Howard galloped around inside his shirt, tickling his ribs, he danced and squirmed and slapped himself, and finally lay down and rolled on the ground. The people on the bleachers thought he had gone crazy, of course, and Jasper kept dancing around him and saying: “Hey, boss! For goodness’ sake! What’s got into you? Hey, quit it; they’re all looking at you!” He was plainly ashamed of Mr. Flint’s behavior.

After a minute Mr. Flint stopped and sat up, for Howard had managed to sneak out again down one sleeve, and had run through the grass to where Bannister was standing and climbed up into his pocket. Mr. Flint looked around in a dazed way, then suddenly leaped to his feet, snatched up the guns he had dropped, and ran for his horse. “Jasper!” he shouted. “You fool, you let that pig get away. Come on!” For Freddy, on his dyed pony, was galloping off across the fields towards the woods.

The first few minutes of the chase were the worst for Freddy, because it was in those minutes that Mr. Flint almost caught up. His tall bay horse was faster than Cy, but Cy was a better jumper and quicker at dodging obstructions. Freddy gave Cy his head, and the pony sailed over walls and ditches, and the pig stuck to his back as if he was glued on, although at the third wall his hat had flown off and he had nearly gone after it, trying to catch it. But he had certainly learned to ride. At each jump Mr. Flint lost ground, gaining it again on the open stretches. But pretty soon they got into rougher going on the edge of the woods—a pasture studded with big boulders and half overgrown with spiny thorn brush—and here Mr. Flint began to fall farther and farther behind. He had fired two or three times, but the bullets had gone wide, and at last he gave up and waited for Jasper to overtake him. They sat staring for a few minutes after the escaping pig, then turned back towards the ranch.