Chapter 15

When Freddy escaped from Mr. Flint, he didn’t go back home, for he had begun to realize what a vindictive nature the man had, and he thought he had better go into hiding for a while. Some time, he knew, he would have to settle with Flint, but he would have to wait until he could think out a good plan. He swung around down into Centerboro and he and Cousin Augustus—for the mouse of course was still in his pocket—rode into the handsomely landscaped grounds of the county jail, which was in charge of his friend, Sheriff Higgins.

The sheriff was at the front door, saying good-bye to a prisoner, Red Mike, whose sentence had just expired. All the other prisoners were there; they had all bought going-away presents for Mike, and Mike had his arms full of them. One of them was a cake with thick chocolate frosting, and the inscription on it in pink: “To Centerboro’s most popular criminal. Come back soon, Mike.” With all these presents in his arms, Mike was unable to wipe his eyes, out of which tears were trickling, for he had been very happy in the jail.

“Well, Mike,” the sheriff said, “we are happy to have had you with us, and if you come back, we will have a big celebration. Of course, I can’t ask you to try to come back, because that would be askin’ you to commit another crime, and that would be a crime in itself—compound-in’ a felony and bein’ accessory before the fact and I don’t know what all. Of course they couldn’t put me in jail for it, because I’m here already. But they might put me out of the jail, which would be worse.

“And I ought to tell you boys,” he went on, addressing the others, “that there’s been some criticism in town of the way I handle things here. Folks say I’m too good to you boys, that lots of you do wrong just so you can get back here, and that I’m causin’ a crime wave in these parts. So I’m askin’ you when you’re out around town, don’t talk too much about the good times we have. Tell ’em I’m a hard man—rule you with an iron hand—that sort of thing. And Mike, don’t go showin’ that cake around town either. If folks see that—” He broke off as Freddy rode through the gate. “Well, now what in tarnation’s this a-comin’?”

Freddy had thought that with his hat gone, he would be easily recognized. But the wig and the moustache changed him so completely that the crowd at the door just stared, and most of them grinned. Freddy stopped, and sat there, pulling his moustache.

“Howdy, gents,” he said. “Sheriff, I’m Snake Peters, from Squealin’ Snake, Wyoming. Been visitin’ the rodeos at some of these Eastern dude ranches, pickin’ up a little change doggin’ steers and such. Well, sir, this mornin’ I’m joggin’ along easy, headin’ west—I been to this rodeo up to Flint’s—when I see two fellers laying up in the bushes above the road. I made out like I didn’t see ’em, but when I was by a piece I left my horse and circled around behind ’em. I figgered they wasn’t there for no good.

“Well, sir, sheriff, they sure wasn’t! I crep’ up and listened. They was part of a band of about thirty cattle rustlers, and the west got too hot for ’em, so they come to do their rustlin’ in New York State. They already rounded up some cows—none of these cows ain’t branded here in the East, you see. All they got to do is put their own brand on ’em—well, they got three cows off a settler named—lemme see—named after some vegetable. I just can’t remember—”

“Maybe ’twas Edgar Cucumber,” said the sheriff. “He lives around here.”

Freddy felt a little suspicious. He was supposed to be kidding the sheriff, the sheriff wasn’t supposed to be kidding him.

“I got it!” he said. “Bean! That’s the man. They got his cows and drove ’em up to Flint’s—he’s in with the gang. If you want to round ’em up, you better get you a posse and go up there. Shore be a feather in your cap pulling in thirty rustlers at one whack.”

The prisoners looked at one another gloomily. The jail was pretty full now, and they had a nice time together. Thirty more guests would mean a lot of doubling up, and strangers, too. It would spoil a lot of their fun.

The sheriff polished his silver star on his sleeve and said: “Well, Mr. Peters, that’s certainly news to me. But I got some news for you, too. There’s a warrant out for your arrest. Let me see.” He drew a paper from his pocket and pretended to read from it. “Snake Peters, long black hair, black moustache, little weasly eyes, large nose, has a very sly sneaky smile—yes, that fits. Face in repose—dirty. Eyebrows—none. Conversation—dull.” He folded the paper. “I guess you’re the Peters we want, all right.”

Freddy saw that the sheriff knew who he was. It was very discouraging. He could fool lots of people with his disguises, but he had never yet been able to fool the sheriff. “Well,” he said, “what’s the charge against me?”

“Impersonating a pig,” said the sheriff, and reached up suddenly and pulled Freddy out of the saddle. Then he snatched off the wig. “There you are, boys,” he said to the prisoners; here’s our man. What’ll we do with him?”

The prisoners all knew and liked Freddy, who often dropped in for a dish of ice cream and a game of croquet. “Stick him in solitary!” they said. “Bread and water.” Red Mike said: “Maybe we’d better string him right up, sheriff. I’ll give him a piece of my cake so he won’t mind so much.”

The idea of cake appealed to all of the prisoners, however, so they all went back in and Mike cut it and gave everybody a piece. Freddy told them his story, and at first they were all for going up to the ranch in a body and taking Mr. Flint apart. But the sheriff said no, he didn’t think it would look well. “You know how people are,” he said. “Always ready to find fault with us.”

“It’s my problem anyway,” Freddy said. “If you can let me have a cell here for a few nights, sheriff, maybe I can think out something.”

So they arranged it that way, and they had supper and after they had eaten up the rest of the cake for dessert, Red Mike said good-bye again and left. And this time he just sobbed right out loud when he went down the walk.

“I didn’t know you could ride, Freddy,” said the sheriff. “Where did you learn?”

“My horse taught me,” Freddy said.

“By George,” said the sheriff, “that is the most sensible thing I ever heard of. Most people get a riding master to teach them. But you go right and hire the horse himself. How are you—pretty good?”

So before it got dark Freddy gave them an exhibition, and then he offered ten dollars to anybody who could stay on Cy ten seconds. Several of the prisoners were Texans who had got chased out of Texas and had come east to continue their professional activities, and naturally they thought they were pretty good riders. But Cy didn’t even have to buck them off; he unseated them all with the same stumble and twist that he had used first on Mr. Flint. Afterwards they sat around on the lawn and had refreshments and talked.

They were sitting there when a strange procession came through the gate. First came the two dogs, Robert and Georgie, going sniff-sniff-sniff as they worked slowly up the drive. And after them came Bannister’s car, chugging along in low, and sounding as if it, too, was sniffing out a trail, with Bannister at the wheel, and Mrs. Wiggins peering anxiously over his shoulder.

The dogs, with eyes and noses on the ground, came sniff-sniff-sniff right up to Freddy, and then they raised their eyes and saw him. They began jumping up and down and yelping with delight, and Bannister piled out of the car and came up, and first he started very politely: “Mr. Frederick, sir, very happy to see you in good health”; and then he forgot his dignity and threw his arms around the pig and gave him a big hug.

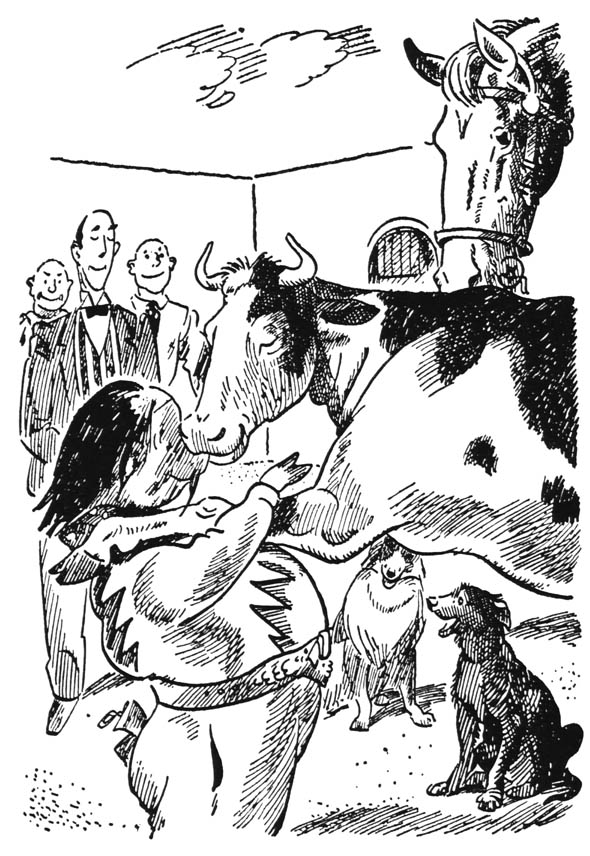

“Will somebody get me out of this thing?” Mrs. Wiggins called. For they had left her in the car. So six of the prisoners ran out and lifted her out, and she came right up to Freddy and kissed him. I don’t know if you have ever been kissed by a cow, but it is a large-scale operation. But Freddy didn’t mind because he was very fond of Mrs. Wiggins.

“We thought you’d been shot, Freddy,” she said, “because Old Whibley found your hat way up beyond the ranch, and it had bullet holes in it.”

So Freddy explained that Mr. Bean was responsible for the bullet holes.

It is a large-scale operation.

“Well, my land,” said the cow, “you certainly had us worried.”

“And you can go right on worrying,” Freddy said. “Flint’s madder than ever at me now, and he’ll shoot me if he gets a chance.”

“Well, you got guns,” said one of the prisoners. “Why don’t you plug him first? Ambush him some night.”

“This is why,” Freddy said, and he pulled out his gun and pointed it at a big window which was about three feet behind him, and pulled the trigger.

“Hey, quit that!” the sheriff yelled, but he was too late to stop Freddy; and then he looked at the window, and there wasn’t any hole in it, and he said: “Gosh sakes, you missed it!”

“ ’Tain’t possible to be as bad a shot as that,” said a prisoner.

“It is for Freddy,” said the sheriff. “I expect he could probably get to be famous as the worst shot in the world, if he set his mind to it. He’s an awful smart pig.”

So Freddy explained about the blanks, and told them the whole story.

“Well, you’re welcome to stay here as long as you want to,” said the sheriff.

“I thought nobody could stay in a jail unless he was a prisoner,” said Mrs. Wiggins.

“Generally speakin’, that’s so,” the sheriff said. “But we’ve made an exception before in Freddy’s case. If there’s any questions asked—well, we don’t have to know he’s Freddy, do we? He’s a dangerous character—Snake Peters, claims his name is. Arrested for prancin’ around town shootin’ off guns and hollerin’ and generally disturbing the public peace and creatin’ a nuisance of himself. And if that ain’t enough, I’ll arrest him for wearin’ that moustache. I never see such a thing in all my born days! Looks like two rat tails, tied together.”

“It was thicker when I bought it,” Freddy explained. “But I guess the hair wasn’t fastened in very tight; it kind of sheds.”

Cy, who had been out in the barn getting some oats, came around the corner of the jail. He stepped very carefully on the lawn, so as not to cut it up with his iron shoes. “Say, Freddy,” he said, “that Cousin Augustus—I guess he had too much cake. He’s out in the barn and he looks kind of greenish. Maybe you better come out—I ain’t much of a hand nursing sick mice.”

So Freddy and the sheriff went out. The mouse was lying on his back on some hay in the manger, and moaning. When he saw his visitors he turned his head from them. “Go away,” he said weakly. “Let me die in peace.”

“No peace for the wicked, old boy,” said Freddy cheerfully. “How about it, sheriff?”

“Kinda fretful, ain’t he?” said the sheriff. He looked thoughtfully at the sufferer. “H’m, I know what’s the matter. We’ve got just the thing for it—just the thing. Yes sir, just the thing for what ails you.”

“Well, you needn’t say it three times,” said Cousin Augustus crossly. “Because I know what it is and I won’t take any.”

It isn’t as easy as some people might imagine to give a mouse a dose of castor oil—even a mouse’s dose, which is one drop. It took the sheriff and two of the prisoners to give it to Cousin Augustus. One prisoner held him, and the other held his nose, and the sheriff got the oil in his mouth and made him swallow it. And even then the prisoner named Looey got bitten in the thumb.

“I wonder how they give the animals medicine in these here zoos,” said Looey when they were back on the lawn. “Lions and like that.”

“Mr. Boomschmidt has a lot of animals in his circus,” said Freddy. “The way he manages it, he’s got a tame buzzard that really likes cod liver oil and such things. Old Boom gets the buzzard to smacking his beak over whatever nasty medicine he wants to give his animals, and then the animals are all so ashamed of being more scared of it than the buzzard is that they swallow it right down.”

“Let’s talk about something else,” said the sheriff, and he swallowed uneasily himself several times. “I don’t know but maybe I ate a mite too much of that cake myself.”

So they talked about other things for a while, and then Bannister drove the dogs and Mrs. Wiggins back home, where the news that Freddy was alive and well was greeted with such a happy uproar that if Mr. Bean had been home, the animals would certainly have got a good talking to. It must have been midnight before they all quieted down and went to bed.