In accordance with the convention established earlier for Italian scripted comedy, the comic scenarios of commedia dell’arte were devised for fixed street settings, however simple their representation may have been in practice, given the expense of set construction and the difficulties of travel for the itinerant performing troupes. In this chapter I first take up the theatrical appropriateness of the fixed street setting and describe the set. I then show how it is of a piece with the life represented in the Scala scenarios, and, in recovering that life, I continue to put on view an important part of the interest that the scenarios would have had for their contemporary audience. I consider the relevance of the urban setting in general and then focus on various of its aspects: houses, inns, night-time, and the street or piazza itself. I move from there to considering the suitability of the street set for the display of certain kinds of behaviour, in particular the presentation of the self, the attacks or perceived attacks on that self-presentation, and the attempts to restore one’s public image. Finally I take up the unrealistic representation of upper-class women in the street. Again I choose these particular matters for consideration because they are omnipresent in Scala’s scenarios.

The action in all but one of Scala’s comic scenarios takes place in what may be either an urban street or a piazza. Day 6 is set in the country but appears to utilize the same kind of road-and-house configuration as does the urban set. Andrews calls the convention of the fixed exterior setting that never allows a scene to take place inside a domestic dwelling “a crippling restriction on the development of [all] Italian comedy.”1 By comparison, English drama of the period, including that of Shakespeare, had no such restriction to an exterior setting, much less to one that was fixed. As Andrews points out, “as long as the setting was restricted to the public street, the appearance of a respectable female either automatically broke social taboos, or else had to be justified by extreme developments in the plot.”2 Foreign travellers to Italy remarked upon the dearth of [upper-class] women in the streets. One Englishman visiting Venice, for instance, commented that “Woemen … if they be chast, [are] rather locked up at home, as it were in prison.”3 Middle-elite women, featured in this drama, could not be realistically represented in the street.

Donald Beecher believes, nevertheless, that the view “that the common setting was deemed an impediment is debatable … for what could whet the creative genius more than the necessity of creating intrigues so specifically timed that all their component parts must flow seriatim through the local square. Much of the dramatic effect of these works is generated precisely by the near collisions, the fortuitous timings, the unexpected encounters and impromptu explanations, the eavesdropping, and the claustrophobic compactness.” The fixed street setting, he argues, provided the scenarist with defined limitations in which to create and generate its characteristic dramatic devices. The very limitation called forth a “consummate skill in the designing of the play.”4

Andrews’ observation that the exterior setting was a limitation to the development of comedy, at least of a particular kind, seems undeniable. I would, however, like to add to Beecher’s comments about the dramatic advantages of the fixed setting.

In addition to the plot mechanisms Beecher has observed, there are other theatrical devices that take full advantage of, and indeed depend upon, the street setting. In Scala the double, often parallel, plots rely upon the simultaneous representation of two familial houses. The public gossip and slander, the night scenes including ghosts, and the mistaken identities (of twins and of those in disguise) are of a piece with or are inspired by the street setting. Similarly, this setting fits, or is required for, the out-of-bounds love, the athleticism (including duels, chase scenes, out-of-breath entrances, characters carrying one another), and the stage business with the props and the set (including travelling bags, a ladder, a door bar, and windows, at which people not only presented themselves but from which they threw bread, a letter, a handkerchief, a glove, or the contents of a chamber pot). The street setting suited the arrival of unexpected strangers in town; it facilitated the representation of a postman, innkeepers, a hangman, sailors, merchants, professionals, henchmen, ruffians, rogues, a fortune-teller, a galley captain, an astrologer, a pimp, policemen, gypsies, an actress, animals, a card sharp, slaves, a mountebank, Turks, Armenians, porters, pilgrims, and beggars. In other words, the street setting allowed the great panoply of characters presented in Scala’s scenarios and the linguistic bazaar they provided, which in itself seems to have served as a source of comedy. The street, as Domenico Pietropaolo has observed, is where “the representatives of all these classes and professions could cross each others’ paths and converse without great prejudice to their social status” – at least, I should add, when they were male or disguised as male.5 The unexpected street encounters required improvisation on the part of the characters and, to the pleasure of the audience, what was, or at least appeared to be, improvisation on the part of the actors.

The street setting allowed for a particular kind of highly regarded “copiousness.” Leon Battista Alberti explained that aesthetic pleasure comes primarily “from copiousness and the variety of things … I say that history is most copious in which in their places are mixed old, young, maidens, women, youths, boys, fowls, small dogs, birds, horses, sheep, buildings, and landscapes and all similar things.”6

The many, sometimes breathless, entrances and exits from many places, together with the abbreviated ending and the condensation of events into a twenty-four-hour period, impart the sense of speed and urgency critical to much comedy.7 So does the double vision provided for the audience by characters both above at windows and below in the street, by disguises and night scenes (in which the audience can see but the characters cannot), by eavesdropping, and by asides – all made possible or greatly facilitated by the street scene. If represented by a perspectival set, the street setting provided the illusion of distance between groups of characters that, as Maggie Günsberg observes, helped make credible the aside as a secret form of speech addressed to oneself or to the audience.8

Finally, the fixed setting not only focused scenic composition for the scenarist but also aided the improvising actors, who would have learned well how to move in the specified place with its windows and doors and who would have been familiar with the kinds of encounters they allowed.

The various activities facilitated by the street setting – the duels, disguises, eavesdropping, and night scenes – too often seem to be but endlessly recycled theatregrams. For their audience, however, the use of a city street as setting, despite the fact that it may have been borrowed from Roman drama by way of the commedia erudita, facilitated the representation in stylized form of early modern life.

The set represented two or three dwellings with openings for windows and doors, facing onto a street or piazza. In Days 1 and 37 there are four houses. For the most part, the dwellings are those of the middle-elite old men, usually Graziano and Pantalone. Occasionally the houses are those of others, and often there is an inn.

The means of representation of the houses in commedia dell’arte was probably dependent on the performance context. We cannot rule out performance on a raised stage in a piazza, with perhaps no more than openings in curtains indicating house doors and windows. But it seems safe to infer that for some years prior to 1611 Scala had enough prestige that he would have been writing in the main for troupes that performed for periods of time in the preferred enclosed and largely interior performance spaces that were favourable to construction of a perspectival set. This would likely have consisted of a painted backdrop, foreshortened paintings on wing drops, and downstage buildings represented by angled wings with useable window openings and doors. In Day 36 Scala refers specifically to a set painted in perspective. Owing to budgetary constraints, a built commedia dell’arte set was probably reused, perhaps with minor alterations, regardless of the various cities designated as the location for the action.9 It was not unusual for the written comedy that so influenced the commedia dell’arte to have been played before a set that represented no particular city. Donato Giannetti remarked in a letter that his Il vecchio amoroso, 1536, set in Pisa, could just as easily be imagined in Genoa. And Machiavelli, in the prologue to his La mandragola, 1524, said quite clearly: “Watch now the stage, as it is set up for you;/this is your Florence;/another time perhaps, Pisa or Rome/don’t laugh too hard, or you’ll break your jaw.”10 In his note to readers in Scala’s edition of scenarios, Scala’s friend, the famous actor Francesco Andreini, explained with reference to the sets for the scenarios that “since in each good city there is no shortage of excellent men, who take delight in mathematics, out of such respect he [Scala] did not want to attempt that which is not necessary, allowing that each could create as they wish every sort of comic, tragic and sylvan set.”11 Andreini gives the impression that the set, requiring skill in mathematics, would have been perspectival but that the specifics of it were no more important than were the particular words spoken by the actors.

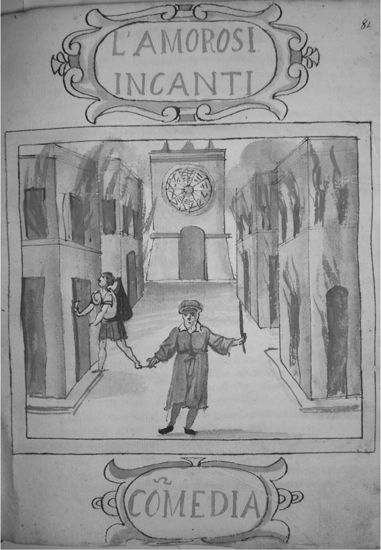

The title pages of scenarios in the Corsini manuscript provide a hundred rather primitive watercolours representing commedia dell’arte from perhaps the 1590s and showing perspectival scenery with some actors within the set, at least to the depth of the front houses and the space immediately behind them.12 Recently it has been concluded that the images sometimes denote a specific event in the text and that otherwise they serve to represent a combination of events based on more than one passage of text or are emblematic of plot elements that cannot be directly related to a specific text passage or to the title of the scenario.13 In the images, doors are at a height that the pictured actors could not have entered comfortably. In one, La commedia in commedia, the play within the play is shown being performed all the way at the back wall. In another, La battaglia, figures are represented in a fort at the rear. Il torneo similarly shows a figure at some depth. Either these figures were painted onto the backdrop, which seems unlikely, or the artist of the title pages simply imagined them deep within the perspectival view. Actual placement of actors near the painted backdrop would have utterly destroyed the illusion of depth.

The Corsini watercolours are nonetheless probably our most reliable guide to commedia dell’arte performance with a perspectival set. They show figures in or having climbed to second-storey windows, and functional entryways, facing front or onto a centre street rendered in perspective. Together, actors at the height of the second-storey windows and at entrances and exits from front- and side-facing doors and window openings allow for considerable variety in the stage pictures, thus contributing to the visual interest of the performance. The space indicated immediately behind the functional two-storey buildings may also have been used for entrances and for hiding. I take these representations of characters at limited depth within a perspectival set and, in one case, L’amore costante, either hiding or entering behind the front set of buildings (figures 1 and 2), to be reliable because we can also see similar representations by other artists.14 It seems less likely that the artists simply copied from one another or independently imagined such entrances for their pictorial interest than that they were representing something they had seen. It is possible that a single reference in one Scala scenario suggests more than the one functional street: “confusamente partono per diverse strade, e via” (in confusion they [the three characters] leave by different streets).15 We can, however, only be absolutely sure that there were entrances from the houses, from stage left and right in front of the houses, and at windows. Day 21 also specifies a loggia or roof where an actor can make an appearance.

3.1. Title page of L’amarosi incanti, Corsinia Album, Biblioteca Corsiniana, Rome. By permission of the Biblioteca Corsiniana.

3.2. Title page of L’amor costante, Corsinia Album, Biblioteca Corsiniana, Rome. By permission of the Biblioteca Corsiniana.

Literary critic Lodovico Castelvetro (1505–71) declared that the set represented should be limited “to that vista alone which would appear to the eye of a single person.”16 The earlier commedia erudita suggests that, in fact, considerable liberty was taken with Castelvetro’s prescription. The set represented the city but not literally; rather, it served as a metaphor for the larger city.17 In the prologue to Pietro Aretino’s La cortigiana, 1525, Histrion 1 explains: “Look there’s the Palace, St. Peter’s, the piazza, the fortress, a couple of taverns – the Hare and the Luna – the fountain, St. Catherine’s – the whole thing.” The city, in turn, served as a metaphor for the world. This is made most clear in the prologue to L’amfiparnaso, 1597: “And the city in which is presented this opera, [is] the great Theatre of the World.”18

The comings and goings of characters in the street or the piazza in Scala’s scenarios invited the audience to envision it as part of a larger reality. This perception was enhanced by offstage voices, specificity about where the characters were going when they exited, and characters’ sightings of characters offstage. In Day 9, act 1, for instance, Pantalone calls for Pedrolino from indoors, and then Graziano calls for Arlecchino from indoors. In Day 6, act 1, Pedrolino leaves because he sees Pantalone and his family and friends offstage, arriving. The setting also predisposed the audience to entertain the illusion that dramatic characters were real individuals who belonged to a community where they lived as ordinary people.19

Altogether, Scala specified a large number of cities as the locales for his action: sixteen scenarios are set in Rome; three each in Perugia, Florence, Bologna, and Naples; two each in Venice, and Genoa; and one each in Pesaro, Milan, Mantua, Parma, and a villa near Padua. In his scenario collection there is no discernible pattern to the cities chosen, and it seems unlikely that the cities mentioned refer to actual performance locales, which were in fact probably largely limited to a northern circuit. Written drama like Ludovico Ariosto’s I suppositi, 1509, was set where it was performed in order to make harmless references to local life or, in the work of Pietro Aretino, 1492–1556, to satirize local phenomena. Whether in performance of Scala’s scenarios the city names were changed to accommodate the places of performance we do not know. When entering a new town, Scala’s Capitano often praises it and sometimes its women. Flaminia in Day 26 praises the city. The actress, a character in Day 39, praises the city, the Duke, the court, and the city’s gentlemen. Although Scala specifies the city in which each scenario is set, with few exceptions (Days 29 and 36, set in Naples), there is nothing in the scenarios that requires the particular locale specified. Opportunities for spoken references to the city in which the performance was taking place may have been afforded by simply changing the name of the city specified by Scala for the action, along with the rare reference to some particulars of that city (like Porta Tosa in Milan in Day 11 or the Florentine eight lords of justice in Day 18), to the name and particulars of the city in which the performance was taking place.

Many cities, place names, and cultural references are mentioned in the Arguments or in the scenarios. In the first scenario in the Scala collection, for instance, Venice, Syria and “other parts of the Levant,” “Alexandria in Egypt,” Persia, Florence, the Prato Gate, Pisa, Livorno, an Armenian, and a Turk are mentioned; in the second, Constantinople, Rome, the Strait of Dardanelles, Sicily, Pantelloria, Bari, Milan, Palermo, Malta, the Pantallarian Sea, and Naples, as well as Pantalone, a Venetian, a Turkish performer, and Greek wine. The picaresque nature of the scenarios is conveyed not by movement of scenes from one locale to another but by reference to the characters’ origins and to what had happened to them before the start of the action. This multiplicity of place references was perhaps calculated to provide a sense of adventure and to appeal to the geographically diverse audiences encountered by a travelling company.20

The Italian city provided audiences for theatre, and thus logically the city was the setting for the scenarios’ comedy. Italy in the sixteenth century was the most urbanized area in Europe and one of the most urbanized areas anywhere, with the possible exception of Flanders. It was made so by the increasing importance of its merchants (like Pantalone), professional men (like Graziano), and craftsmen and tradesmen, who naturally gravitated to business centres.21 A third of the Italian peninsula was urban. In 1550, forty towns had populations of ten thousand or more and, of those, half had populations over twenty-five thousand. Naples, Venice, Milan, Palermo, Florence, Genoa, and Bologna each had populations of sixty thousand or more. And these urban populations were lower, in some cases much lower, than before the plague had struck. Thereafter the urban populations continued to rise.22 They rose despite the fact that even in non-plague years the mortality rate was extremely high; the recorded excess of deaths relative to births was probably largely among the poor and numerous peasants relocating to the cities.23

Excluding towns that served principally as administrative centres, the large Italian cities were primarily commercial centres, seaports, banking networks, or centres of textile production.24 The merchant Pantalone, the professional man Graziano, the wily servant Pedrolino (determined to make his way), and the perennially hungry Arlecchino (the latter two both relocated peasants) would all have been familiar urban figures. Reflecting the general age of the population, these are plays of youth. In Venice where we have information from between 1610 and 1620, over half the population was under the age of thirty.25 The successful exploits are those of the young – servants and lovers alike. The old, or rather those that seemed old at the time and to the young, do not generally fare well.

In 1455 Marsilio Ficino made clear the relationship between house and family, casa and famiglia; “the house,” he said, ‘is nothing other than the union of the father with his sons in one residence,” the father’s house.26 The houses that we see on stage in the scenarios are at one with the family dramas represented. They stand for the structured world of authority, kinship obligations, and obedience. By the time Scala was writing, however, “the house” may have referred not to the extended family that Ficino had envisioned but to the kind of nuclear families we see in Scala.27

The houses usually had two floors, although in the larger cities, where space was at a premium, they might have had three. The main door was massive, iron bound, barred, and locked with a large lock and bolts supplemented with chains. In appearance and in fact, it needed to be capable of withstanding assault, which was a real possibility.28 Most of the extant renderings of houses in the commedia dell’arte show them as two storeyed. In Scala the door and the attempt to gain entry could be a focal point of the action. In one scenario, Day 35, acts 1 and 3, a door bar plays a comic role. Edward Muir’s comment that the threshold of the house often served a ceremonial purpose – reinforcing the transitional or liminal phase of the rites of marriage – suggests the possible location of the taking of right hands to signify agreement to marry.29

Günsberg points out that the fixed exterior setting of the scripted commedia erudita required that, when characters wished to talk without being overheard, they came out onto the street, thereby providing a pretext for being out of doors and onstage, rather than indoors and offstage.30 In the first scene of Ariosto’s I suppositi, 1509, Polinesta is instructed by her nurse to come outside Damone’s house in order to avoid household spies: “There’s no one around; come out, Polinesta, into the street, where we’ll be able to see around us, and we’ll at least be certain of nothing being overheard by anyone. I think in our house even the bedsteads, the chests and the doorways have ears.” Similarly, in Bernardo Dovizi da Bibbiena’s La calandra, 1521, the adulterous Fulvia decides that it is best to speak to the sorcerer “out here because inside, the benches, the chairs, the chests, the windows all seem to have ears” (act 4, scene 1).31

This contrivance, also employed in Scala’s scenarios (see, for instance, Day 21, act 2) may not have seemed as improbable at the time as it seems to us now. Upper-class women, to be sure, stayed within and would not have come out into the street to speak. But the house, in fact, provided little privacy. The front door opened directly into the main room, and the interior was essentially a shell subdivided by wooden partitions. Rooms connected immediately with each other, and the space-wasting corridor was used only in large buildings. One of the few places for privacy in the house was the canopied bed, about which curtains could be drawn to make a little private room, but even such privacy might be limited by a servant’s truckle bed beneath it.32 Also, to a greater extent than we might suppose, the street was an extension of the house and often afforded more privacy. Andrea de Jorio observed in 1832 that in the crowded city of Naples the street was, in effect, an extension of the house or apartment and that, therefore, it was more accurate to say not that Neapolitans do everything in the street but that they “do everything in their house” (his emphasis).33 Naples is warmer than the northern cities, and de Jorio wrote two hundred years after Scala, but his observation seems worth bearing in mind.

An ordinary day’s journey would have averaged about forty kilometres,34 or even less on foot. Given the great number of people on the move, inns were a central feature of the city, intermixed in the heterogeneous street setting, as they are in Scala’s scenarios. Scala makes frequent use of them for the stranger come to town who initiates an important plot element. The few actual women travellers would have been in gypsy bands or commedia dell’arte troupes, or they would have been army-camp followers (wives, mistresses, prostitutes, laundresses, food gatherers, and nurses). The women travellers in the Scala scenarios are generally in disguise, often as male. I will have occasion to discuss them in the third major section of this chapter.

The night scenes extended the single day in which comedies were to have been set. Night, like cross-dressing, also served as one of the many kinds of disguises for the characters and facilitated hiding and covert activity, including romance, escapes, and break-ins. Undoubtedly it also lent itself to a lot of comic peering into the darkness, terror, mistaken identity, and bumping into and falling over things and one another. It was one of the many comic devices that allowed the audience to feel superior in knowing what the characters did not know, in this case, because they literally could not see. It was also an iteration of the contemporary drama’s preoccupation with the irony of sight and blindness, appearance and reality. The exterior setting facilitated the many night scenes in Scala’s scenarios.

Lacking artificial light, night in the early modern street was, in point of fact, dark. It had particular significance in Italy where the hours were counted not from the sun’s meridian but from its setting. Ora di note and due ore di notte are respectively one and two hours after dusk. In accordance with God, day belonged to work, and night to sleep.35 The distinction made between “Apollonian, virtuous, luminous and active time, and demonic time” was very clear. Where a compulsory curfew was not in force, men knew to be off the streets and safely behind barred doors. As Sabba Castiglione apprehensively warned in 1554, “you will be on your guard when walking at night, if not out of extreme necessity, firstly against scandals, inconveniences and dangers which lurk there continuously; then against the various and diverse infirmities which are often generated in human bodies by the night air … It is certain that going out at night without need is nothing other than disturbing nature’s order.”36 Night was a time of disease and crime.37 More than that, night in and of itself was a reminder of death: “God created the distinction between day and night for a particular purpose, and that purpose is to serve as a reminder, even a paradigm, of the cycle of death.”38 To know that night was approaching was to be reminded that death was round the corner and to be reminded of all that that implies for the conduct of one’s life. As late as 1782 the Jesuit Giulio Cesare Cordara argued against the adaptation of French time, which was counted from the sun’s meridian, because it downgraded nightfall to an incidental occurrence that had no definite hour to call its own.39 The representation of night was a representation of danger. To evaluate Andrews’s comment that Scala overused ghost scenes,40 one has to appreciate the real anguish invoked by the night: it belonged to terrifying apparitions, ghosts, goblins, spells, and collective hallucinations spread by uncontrollable rumours. The perceived porous or permeable nature of the body in the period41 meant that ghosts were regarded as real. “All it took was a ghost – a supposed masked apparition – to throw a city into confusion and fear.” In Modena, as late as the eighteenth century, fear of a spirit provoked a collective hysteria.42

David Wiles makes the important observation that piazza is a Latinate term with, significantly, no German or English equivalent, “signifying the ‘place’ that matters, the centre of the community, the space for collective performances.” The genius loci of the sixteenth-century piazza is strong; it is the centre, the seat of collective memories, “where natural topography requires journeys to begin and end.” Citing the cultural geographer Don Mitchell and the sociologist Henri Lefebvre, Wiles points to the urban ideal of the “public space” characterized by the piazza as one associated with interaction, inclusiveness, and conflict, and subject to constant metamorphosis; its rhythms were constituted by promenading, trading, and scheming.43 The piazza was a space to which people gravitated, and the scenarios reflect this. It is, to use a slang expression, “where the action is.”44

The climate and the lack of interior space encouraged the preference for a life lived in public. Documenting the family life of three distinguished families in Florence, historian Francis Kent notes that their formal meetings, except perhaps for their more private business, were conducted in the street and piazzas near their houses and palaces. One of the families had a wedding feast in the small open area ringed by their family houses.45 “Men’s lives were dramas played out in the streets and other civic spaces.”46 Unlike the impersonal, socially segregated society that one associates with modern urbanization and economic development, Italian sixteenth-century society and capitalism were intimate and personal.

In this face-to-face society, people continually crossed paths in the performance of daily activities, both public and private.47 The basic units of Italian social organization in the closely packed towns throughout the early modern period remained family and neighbourhood. The early modern city, even a large one, was in many ways a confederation of villages. The neighbourhood or vicinanza provided a tightly knit informal grouping that linked the members of the same parish or the neighbours bordering the same piazza.48 Dale Kent and Francis Kent describe the neighbourhood as “a stage on which many of the events of a man’s life were acted out with the co-operation and participation of his parenti, vicini, and amici.”49 One was always under the watchful eyes of friends and neighbours. Newcomers to the neighbourhood could not stay strangers for long. Everyone knew everyone else. As in the scenarios, the street and the piazza were arenas for personal, sometimes emotional, social interactions. These were at home in the street setting.

In his introduction to his English translation of Andrea de Jorio’s Gesture in Naples and Gesture in Classical Antiquity, 1832, Adam Kendon tries to account for the elaboration of gesture in Naples: it allowed private communication and communication over noise, at a distance, and in both the verbal and visual medium, not necessarily consistent. Although the climate of Naples was, as I have noted, particularly conducive to a life lived out of doors year round, Kendon’s observations pertain to the whole of Italy and to the sixteenth century as well:

for much of the time, people were always co-present in spaces only partly well-bounded and screened, not only with members of their own family but also with others, most of whom would have been at least acquaintances. Life, all facets of it, tended to be carried out … always in the presence of a widening range of possible witnesses. Even the most private relations either were public or could become public at any time.50

Personal privacy was virtually unknown.51 The theatrical convention of the comment aside was consistent with the street setting, where one might realistically overhear private conversation.

The mixing of high and low classes in the neighbourhoods, which may seem to modern readers to be mere theatrical convenience, preserved the economic and social practices surviving from the formation of cities in the Middle Ages.52 The neighbourhoods contained both the poor and the rich (whose palaces, essentially fortresses, provided them with a measure of seclusion), and the members of many different professions. Their daily proximity and the presence of foreigners made the early modern city a place of social uncertainty and potential danger.53 The panoply of figures entering the street scene in Scala’s scenarios – pilgrims, gypsies, merchants, beggars, and soldiers – would not have seemed out of place or their unexpected interactions altogether improbable. Historian Peter Burke observes that while the literary multilingualism may have been comic, the humour may also have been, at least in part, a humorous-hostile reaction to country people and foreigners in the towns.54

Male life was lived in public on the square. Indeed, there was something shameful about a man remaining at home indoors. While “it would hardly win us respect if our wife busied herself among the men in the marketplace, out in the public eye,” remarks a cousin in Alberti’s Della famiglia, expressing a common view, “it also seems somewhat demeaning to me to remain shut up in the house among women when I have manly things to do among men, fellow citizens and worthy and distinguished foreigners.”55 Merchants conducted their business out of doors in places like the Rialto in Venice where they could be seen bargaining before the eyes of spectators.56 (Artisans would also have been seen in the street making and selling their wares, but they play no part in Scala.)

Male servants, central to the scenarios, could be seen going about the streets alone, dispatched to collect bills, receive goods, deliver messages, and run various other errands,57 or with their masters whom they served to escort about the city, clearing a path for them through the crowds during the day or providing them with lantern light at night. They were expected to protect their masters from danger, if need be, by engaging with them in their quarrels. In a humorous reversal of this expectation, in Day 35, act 2, Arlecchino ducks out of a quarrel to which his master, the cowardly Capitano, has been challenged, with the same preposterous excuse just provided by the Capitano.

Serving women could be seen at the windows, lowering baskets for the postman or baker. Their disposal of waste fluids from windows inevitably became a source of comedy (see for instance Day 35, acts 1 and 2). Serving women too were dispatched to run errands, which in real life they frequently did with scarved faces in an attempt to protect themselves from the danger of the streets.58

Another street activity represented in Scala (Day 12), although surprising, was also realistic. Dentistry, the profession of barbers and itinerant quacks, was often conducted on seated patients in public places. Other public acts that may surprise us include the procession of a condemned man through the streets, and other public punishments, as shown in Day 18, act 2.59 Pantalone, frequently driven to despair, had many opportunities to express his rage tearfully in the street. Rage, piety, and grief found expression in tears. Men openly weeping in public was not regarded as unusual or unseemly, at least on certain occasions.60 In Day 5, act 1, Flavio weeps because he believes that Isabella has betrayed him. In Day 24, act 1, Pedrolino, unjustly charged by his master, weeps in humiliation.

The vitality and variety of the street scene was represented not as it would be at one moment but cumulatively over time and at both levels of the houses in the many scenes of Scala’s action-packed, fast-moving scenarios.

People worked hard at creating and maintaining impressions, at manipulating reality to serve their own ends. In public spaces people performed themselves as they wished to be seen. The male sense of identity was affirmed by the successful performance of self with style, fare bella figura. Italy was what Peter Burke calls a “theatre society.” The facade was far more important than the reality.61 Showing off, self-presentation, was synonymous with life.62

The public square was ideally suited both to such performance and to its observation. Indeed, the architect Leon Battista Alberti regarded the public square as specifically suited to the framing of public action as performance: “Glory springs up in public squares; reputation is nourished by the voice and judgment of many persons of honor, and in the midst of people.”63 Urban historian Alexander Cowan argues for the very close relationship between the stage set that was based on the rules of perspective and the late sixteenth-century reshaping of public squares that were intended for the “dramatic presentation of the elite, both to each other and to observers.”64

Disguise, so prevalent in the scenarios, was a regular part of life, albeit without a mask or a costume, and not just at Carnival (a time of special liberty from normal rules and social hierarchies that extended from late December or early January to Shrove Tuesday, the eve of Lent). Historian Eric Dursteler points to the extent to which “dualistic self-presentation was widespread throughout the early modern world.”65 The sprezzatura that Castiglione recommended for courtiers – the cool nonchalance that concealed all art and made whatever they said or did appear to be effortless and almost without any thought about it – was a kind of disguise. The culture of craft and craftiness was pervasive. In 1609 the Venetian lawyer and historian Paolo Sarpi observed that he was, in effect, “obliged to wear a mask, because no one in Italy may go without one.”66The mask was a common metaphor for dissimulation in early modern culture. No one knew with certainty whether the face was “already a mask and its owner no different than an actor in a comedy: in the culture of secrecy, the natural was always already artificial.”67 Imposters were potentially everywhere. It was an age of dissimulation in Europe.68 The French nobleman Louis d’Orléans lamented in 1594 that it was impossible to know the true identity of the dissimulator; all were left as if “in the darkness of night.”69 Adovardo, in Alberti’s treatise on the family, declared that everything in the world was profoundly unsure and that the world was filled with deceitful, false, perfidious, bold, audacious, and rapacious men. In the face of the many traps such a world provided, one had to be continually “far-seeing, alert, and careful.”70 In a society in which many people were impoverished and in which appearance was cultivated and deceptive, suspicions ran high. People might not be what they seemed. Surveillance was critical. Not surprisingly, the eavesdropping evidenced in the scenarios was a major literary motif.71 The period’s characteristic consideration of the limits of human perception and of the capacity to make distinctions was of a piece with the prevalence of dissimulation.

A century and a half before Scala published his scenarios, Leon Battista Alberti forcefully explained the centrality of honour: “[Honor is] the most important thing in anyone’s life. It is one thing without which no enterprise deserves praise or has real value. It is the ultimate source of all the splendor our work may have, the most beautiful and shining part of our life now and our life hereafter, the most lasting and eternal part … Satisfying the standards of honor, we shall grow rich and well praised, admired, and esteemed among men.”72 It was the supreme social value. Virtually everyone, rich and poor alike, male and female, saw honour as more dear than life itself.73 Dale Kent came across the following telling anecdote from about the same time: Manetto Amannatini was invited to a dinner party with twenty-two friends, almost all of higher rank and status than he. When he did not appear, the friends were miffed by his unexplained absence. They decided to revenge the insult with a practical joke; they treated him as if he were no longer Manetto but someone called Matteo. Having been thus humiliated and dishonoured, Manetto moved to Hungary.74 In various ways, reflecting the continuing central concern about it, each of Scala’s scenarios takes up the issue of honour: its loss, or the struggle to maintain it, or gain it. Honour had altogether to do with public perception. It existed entirely in the eyes of other people and disappeared when their favour was lost. The street was the natural setting for maintaining honour, the “good opinion others have of us.”75 A man’s honour derived primarily from his success in business and public life, and it was understood differently according to class. Children, servants, and wives whose character was excellent proved the diligence of the husband and father and brought honour to him, the house, and the country.76 An orderly society depended upon the good sense of and control by its adult men. Social historian Elizabeth Cohen explains that an attack on honour is anything which shows to the audience of society that a man cannot protect what is his – his face, his body, his family, his house, his property.77 One family member’s fall into dishonour cast doubt on the authority and power of the family, proving its weakness and inability to defend its reputation. Scala’s comic scenarios variously pose the threat of dishonour that could be brought upon a family by its members. Patriarchs could bring dishonour upon themselves with their gullibility and foolish lusting after young girls and obviously unobtainable women. Children, servants, and the occasional wife represented in the scenarios could, and regularly do, present a threat to the honour of the patriarch and the family as a whole. One might understand the scenarios’ inevitable love matches as merely occasions for raising issues of honour.

A woman’s honour (or rather her absence of shame) was defined, as we know, by her chastity.78 Women who did not abide by their husband’s or father’s control of their sexuality were regarded as “immodest” or “shameless.”79 Even the appearance of immodest behaviour was a concern. A proper upper-class woman or girl was not even to sit at her window, idly watching the activity in the street. Sizing up a possible marriage partner for her son, the widow Alessandra Strozzi made note of the fact that she “had not seen her looking out of the window every day, which was a sign that she was not frivolous.”80 A low profile, silence, and a consistently modest demeanour indicated that women knew their place in the social hierarchy and served to avoid any hint of sexual provocation. To engage in conversation from the window gave the wrong impression. Conversation across social classes and between genders was associated with liberty and promiscuity.81 “A man might court a girl at her window only by serenading her and even then in the fellowship of other men.”82 The scenarios regularly show upper-class women both at windows and in the street talking to men, and thus honour becomes an issue in ways we may too readily overlook.

In the streets the chastity and fidelity of women were at risk. Like the representation of night, the representation of women in the street was a representation of danger. In the street, women might act upon the temptation to interact with men or otherwise put themselves in harm’s way. The streets and alleys were narrow and unlit, unknown persons lurked about every corner, the police were hardly efficient, and females were in fact always vulnerable to robbery or sexual assault, particularly because unlike men, who regularly carried either a dagger or a staff for purposes of self-defence, they did not go about the city armed.83

While upper-class girls were sheltered and married off at a young age, upper-class males presented a challenge to civic society, which depended upon a disciplined citizenry.84 In their prolonged adolescence under their fathers’ rule – at least until marriage, when they were admitted to full manhood85 – they constituted some of the primary denizens of the illicit world.86 Scala’s repeated representation of upper-class youths in street fights and in inappropriate pursuit of young girls and women, widowed or married, disrupting their fathers’ plans and the general neighbourhood, as I have indicated, seems scarcely to have been an exaggeration. The unruly behaviour of young unmarried men provoked fathers’ tirades in Scala and, no doubt, in real life.

While the upper classes regarded threats to the padre di famiglia, whether from offspring or servants, as threats to the city fathers and to the whole of the social hierarchy, public acts of disobedience, the kind we see repeatedly in Scala’s street setting, were considered especially grave because honour was a matter of public perception.

No one was immune to insults and gossip.87 Insults could readily damage one’s honour and were taken very seriously. For women, who were less able to resort to physical violence than men, such insults were powerful tools and were freely used.88 However, they were not only the tools of women. Insults by inferiors to superiors, and especially in public, were particularly grievous.89 Insults could lead to gossip. Gossip, even women’s gossip, was a potent form of power that could both create and destroy honour.90 In the small-scale communities that made up the city, gossip spread quickly. The prevalence of gossip meant that dishonour was widely disseminated and hard to live down.

Ordinary speech was rich in insults against both men and women. Slurs against a woman included the terms liar, fool, coward, witch, procuress, but most of all adulteress, whore, dirty whore, or poxy whore. These latter and most serious insults make clear that defamation of a woman’s character consisted primarily in calling into question her chastity and fidelity in marriage. In The Book of the Courtier the speaker identified as the playwright, Bibbiena (Bernardo Dovizi da Bibbiena), observes that for men “a dissolute life is not thought evil or blameworthy or disgraceful, whereas in women it leads to such complete opprobrium and shame that once a woman has been spoken ill of, whether the accusation be true or false, she is utterly disgraced forever.”91 As the qualities of men’s honour were more various, so were the insults: liar, thief, rogue, traitor, coward, spy, bugger, pimp, and cuckold.92 Accusations of dishonesty directly attacked the honour upon which a man’s business and social relationships depended, and so called into question his success and stature as a merchant, tradesman, artisan, or labourer. Still nothing was worse than calling a man a cuckold, accusing him of his inability to control or satisfy his wife, and thus threatening the very foundation of the patriarchy. The term makes clear that a woman’s honour was never solely her own.

There was not only a rich verbal vocabulary to impugn someone’s honour but also a rich gestural one. Such gestures included sticking out one’s tongue at an enemy, pulling a man’s beard or a woman’s hair, singing lewd songs in front of the house of an enemy, spitting in his face, knocking off his hat, and making hand gestures that implied that she was a whore or he was a bugger or a cuckold.93 There was also the public charivari-like shaming, which served the function of group social control by humiliating those individuals who stepped out of line and discouraging other breaches of custom.94 Thus in Day 6, without even promising her marriage, old Graziano wants in the worst way to go to bed with Flaminia, an upper-class (and probably young) widow. Pedrolino serves Graziano right by arranging a bed trick in which Graziano lies with a lower-class woman instead and is disgraced at the exposure of this before a large crowd. The larger the crowd, the greater the humiliation.

Lesser insults might be counter-attacked with quick, often witty or biting verbal skills. Effective responses and threats could sometimes stave off violence by allowing participants to verbally repair their honour before the court of public opinion.95 But defamation of character could also easily lead to blows.

The many verbal fights, chase scenes, and duels in Scala’s scenarios may seem to us now to be merely dramatic, even overused, melodramatic devices. All, however, need to be understood in the context of the ready verbal abuse and violence of the sixteenth-century Italian society. At Carnival, sometimes the setting of the Scala scenario, drunkenness and a high degree of sexual licence frequently led to street violence and civil commotion. The masking and the disguises often enabled the perpetrator to remain unidentified.96 A regular, brutal Carnival amusement consisted of watching or volunteering to participate in a melee of blindfolded men who were trying to break an earthenware pot on the ground with long cudgels. The first to break the pot got the prize contained within the pot.97

Verbal and physical violence were not limited to Carnival, nor was drunkenness regularly a significant problem; there was much less of that in Italy than elsewhere in Europe.98 Violence was endemic. One cause was the number of starving poor flowing into the towns, their overcrowded living conditions, and severe competition for jobs and food.99 However, the poor were by no means the only cause of violence. Social relations in general, marked by suspicion, jealousy, envy, and rivalry,100 led to the explosive, murderous quickness of the sixteenth-century Italian temper. It was not mere theatrical convention but a fact of life. However, in life, as opposed to comedy, the consequences of the fights were often grave. A single thrust of the rapier could be fatal. Gentlemen wore swords, not merely for decoration but for violent and sudden use.101

The pretext for violence was often trifling: a simple contradiction, the mentita, could be enough to spark bloodshed.102 Over and over again in Scala’s scenarios the immediate precipitant of a fight is calling someone a liar. In Day 33, act 1, Flavio says that Orazio is a traitor. Overhearing this, Orazio’s servant Pedrolino calls Flavio a liar. As a result, Flavio draws his sword. While the young men of every class were particularly willing to risk death, maiming, or exile on the spur of the moment and constituted a rowdy menace in the streets,103 no one was immune. To resort to force was a sign of social superiority; to be sensitive to slights and to be bellicose, belligerent, and otherwise always spoiling for a fight was to imitate the behaviour of the great and the good. Turning the other cheek to a challenge was a sign of contemptible weakness and stupidity. Mantegna hired thugs to beat up a rival, Michelangelo had his nose broken in a fist fight, and Caravaggio killed a man over a tennis match.104

The evidence of violence is more than anecdotal. There are a multitude of court records of criminal legal cases brought by peasants and artisans in which angry words had quickly escalated to serious and lethal woundings.105 These cases do not begin to tell the full story of the extent of the violence, because to resort to a court of law in the matter of a private dispute was to risk being thought cowardly and stupid. It was far more honourable to take matters into one’s own hands.106 In Scala’s scenarios, youths regularly invoke violence; recourse to the legal system is rare. Even Scala’s old men fight one another. In Day 29 old Pantalone accuses old Graziano of conspiring with Graziano’s son Flavio to help Pantalone’s daughter run off with Flavio. Graziano responds that he is lying through his teeth, and the public fight between them is on. Acts quite regularly end with characters exiting, their swords drawn, and chasing one another. Historian John Hale notes that the popularity of fencing lessons among the upper classes in the sixteenth century reflected not just some new fashion in a costume sword, the rapier, but the need to be prepared for the high incidence of violence that could follow even a jostling on the street.107 City life afforded frequent occasion for taking offence and provided a wide audience for one’s bravado, certainly a wider audience in which to win or lose one’s reputation than did the countryside.108

One of the primary causes of violence – perhaps the primary cause – was defence of honour. To fail to avenge an injury, no matter the cause, was to lose honour; it was to suffer a loss worse than death.109 Social historian Gregory Hanlon notes that “young men challenged in public were ready to swing out at acquaintances for reasons historians often find to be pointless, but they were acting with the same concern for their reputation as heads of families.”110 While, “according to the traditional values of the culture, the honorable man must retaliate when attacked or lose his honor … according to the laws of the state, if he retaliates, he is likely to suffer arrest, confiscation of his property, and exile or execution. If he does nothing or relies on the law courts to exact justice for him, he appears the coward, loses his honor, and makes himself vulnerable to future assaults and the unpredictability of the judge.”111 In Scala’s scenarios, as in life, honour takes precedence over the law. A true gentleman tolerates no stain to his name and upholds the chivalric ethos to the death. In most of the scenarios in which he appears, Capitano Spavento is a figure of mockery because, despite his vainglory, the audience knows (as he explicitly says in Day 37, act 3) that, if it comes to that, he will suffer any indignity to avoid death.

It was a further point of honour to fight as quickly as possible after an insult had been given and satisfaction demanded. Taking time to think was tantamount to a declaration of cowardice.112 The sudden escalation from verbal exchanges to drawn swords in the Scala scenarios is realistic. At the end of act 2, Day 33, Arlecchino tells Flavio that he, Flavio, will never have the woman he loves. At that, Flavio becomes enraged and draws his sword on Arlecchino.

The defence of family honour was as important as or even more important than the defence of individual honour, and a man was expected to defend it even with his life.113 Any slur on the family’s integrity or ambition called for retribution. Defence of the family honour could entail long-term hostilities that passed from one generation to the next.114 “Just as honor was something one inherited (and which like material wealth, could then be squandered or increased by one’s own actions), animosities and alliances were also inheritable.”115 Guicciardini, 1530, explains the account-book model of revenge: “it is perfectly all right to avenge yourself even though you feel no deep rancor against the person who is the object of your revenge.”116 Scala’s Day 18 begins with Orazio returning to Florence in protective disguise because he believes that some months ago there he had killed the son of the Doctor who was a long-standing enemy of his family. Honour killing was illegal.

In Scala the upper-class youths threaten one another with duels. This method of fighting was the exclusive prerogative of those who bore arms by profession or by hereditary right: officers, nobles, and gentlemen. Duelling sustained the prestige of a class and also of the male sex, assigning men the role of natural guardian and protector of women.117 Thus it is that in Day 25 the Capitano grandiosely comes to the defence of Isabella, whom he does not even know. Members of the lower class were left to clubs and sticks, exemplified by Arlecchino’s ever-present bastone. Women, as Scala shows, resorted to bare hands (or hair pulling). In Day 17, after some name calling (specifically, Flaminia calls Franceschina a “bawd”), the two women engage in fisticuffs. Angry words quickly led to blows. Duelling and brawling mixed; two-on-two and crowd-on-crowd encounters were common; the duelists’ “seconds” participated – they did not just watch.118 In Day 1 Arlecchino comes to take revenge for the slap he received from Pedrolino. When he beats Pedrolino with his stick, all those present on stage – Flavio, Orazio, and the Capitano – join in the fight, and all exit fighting along the street.

While in the Scala scenarios there are few fights that result in injuries, many, including murders, are recounted in the Argument preceding the scenario, which would have served as exposition in the course of performance. The absence of actual physical violence had a basis in reality. Many of the quarrels in real life had a distinctly theatrical quality. They proceeded by a ritualized sequence of words and gestures that could be all the more violent because the opponents could count on being separated by their friends before any serious harm could be inflicted.119 Scala shows near-death fights in which a friend intercedes. In Day 2, act 3, when Orazio and the Capitano enter fighting, Cinzio and Flavio intervene and stop the fight. The threatened duels and chase scenes that end acts almost never result in any evident untoward effect. In the rare cases that physical harm is actually inflicted in the course of the action, in Days 29 and 38, the victim recovers fully and uneventfully. Most important was to give the appearance of being ready to defend one’s honour at all costs, because once it was lost it could not be regained.120 Perhaps the absurd excuses that the Capitano provides for sidestepping a duel recall the elaborate formal rules for duels. The duel provided a ritual frame to regulate private combat.121

The elaborate formal rules and protocols for duels that were propagated in popular manuals followed the anti-duelling decrees issued at the final session of the Council of Trent, 1564, and both the decrees and the manuals seem to have resulted in some decline in duelling in Italy.122 In the frequent representation of duels or threats of duels, Scala seems to harken back to an earlier period, as he does in the dramatically expedient marriages, which take place without benefit of clergy, and in the intended hunts:123 by the end of the sixteenth century, the game had been all but hunted out.

Thus far, in this chapter, I have shown how well the fixed street setting served the drama. I have also argued in specific detail the extent to which it accorded with and served to imitate life in what we might think of as a kind of heightened realism. The sixteenth-century Italian city, houses, travel, inns, night, the piazza itself, the male presentation of himself, disguise, eavesdropping, the aside, honour, gossip, insults, and violence are all central to Scala’s scenarios.

At the risk of appearing to defend the limitation to the requisite street setting no matter what, I want to argue in the last section of this chapter that it was a limitation that was salutary for both theatrical and, from our point of view, socio-political reasons precisely because it was not realistic.

Scala acknowledges the restriction of women to their homes, often by having them appear first at their window, and even there alone and silent, as observers to the action below. Jane Tylus has counted 120 appearances at a window in the Scala scenarios. Of these, 109 are made by women, including women of various marital and social statuses.124 In the relatively safe liminal space of the window the women sometimes go unnoticed by those in the street below. And from the window they can readily absent themselves. When upper-class women come into the piazza in the Scala scenarios, Tylus observes, they may be framed by a doorway and thus are only tentatively present in the public space.125 Even when extraordinary developments in the plot bring the upper-class women out into the street, they often appear in protective disguise or – without regard for such protection – mad. The disguises are of considerable range, including those of a pilgrim, a gypsy, an astrologer, a servant, a porter, a page, a ghost, and a madwoman. Even the disguises do not leave the women safe; as gypsies and servants they are shown to be fair sexual game.

In eighteen of Scala’s forty comic scenarios the primary inamorata disguises herself as male.126 In real life women did disguise themselves as male and not just during Carnival, when their disguises may have been deliberately easy to see through. Rudolf Dekker and Lotte van de Pol provide ample documentation from the Netherlands of travel by women in disguise.127 From the sumptuary laws against cross-dressing in Italy, Laura Giannetti concludes that the practice was widespread there. Transgression of the codes governing dress disrupted the official view of the social order in which identity was largely determined by station or degree and which was, in theory, providential and immutable.128 Women in men’s clothes symbolically became masterless women, and as such they threatened the hierarchy.129 They also risked the loss of their virginity and of the family’s honour. Women travelling are known to have so disguised themselves, particularly on long trips, to make themselves less vulnerable to the frequent highway robberies. Masculine attire was also more practical than travel in a skirt. In Italy young women could successfully pass as young men because the early teenage years of both males and females were seen as sexually androgynous.130 There was, however, always the risk of discovery resulting in an even greater risk of sexual assault: courtesans and actresses sometimes dressed in male attire because men found it erotic. Thus, while male disguise allowed females the freedom to move outside of the house, to express a spirit of initiative, and even to speak in public, the acute risks involved always contained tragic potential.

However frequent the women disguised as youths may have been in real life, it is most likely that their frequency in Scala’s scenarios serves dramatic purposes and expresses societal fears more than fact. Disguise is, of course, intimately related to drama; onstage, actors appear to be other than who they are. In the scenarios, women’s disguises, like the women’s appearances at the windows, acknowledge the impropriety of women in the street. And, just as in reality upper-class women would not ordinarily have appeared in the streets, they would not have appeared in disguise. However, like women in the street, the effect of the disguises on the drama and on the culture was, from our perspective, beneficial.

In commedia dell’arte, unlike in the commedia erudita, actresses, not actors, played the roles of females. The disguises, as M.A. Katritzky makes clear, allowed these actresses to escape from the domestic space of women to a variety of roles that permitted them to more fully explore and realize their potential as performers. Actresses “created and starred in a wide range of disguises, drawn from the spheres of gender, race, age, mental competence and social class … as creative passports to new dramatic territory – in terms of performance modes as well as theatrical space – traditionally monopolized by men.”131 The skill of the actresses in these roles may have suggested, by extension, the capabilities of women. And by bringing actresses into roles that they would otherwise not have had, at least in the instance of some performers (like the celebrated Isabella Andreini and Vittoria Piissimi), the street setting, ironically enough, aided in elevating the status of female performers above the perception of the actress as whore. Both Isabella and Vittoria were invited to perform for the wedding of Grand Duke Ferdinando de’ Medici in 1589, and Isabella was invited to became a member of the learned Accademia degli Intenti. Within the troupes the popularity of the female performers, Ferdinado Taviani argues, disrupted the usual sexual hierarchy in “the evident need to recognize a greater weight for those who – regardless of their sex -contributed the most to the success of the company.”132 Some women even became troupe leaders.

The roles themselves may also have served women. I turn to the observations made by Jean Howard about cross-dressed female characters in English drama and to those made by Laura Giannetti about them in the written Italian drama. Their observations can readily be extended to the Scala scenarios.

Jean Howard remarks that one social function of the cross-dressed role was simply “the recuperation of threats to the sex-gender system” at the end of the play where the woman assumes her rightful place in marriage subject to male domination. At the same time, though, Howard points out that the recuperation is never perfect. During the course of the play a space had been opened up for women’s speech and action.133 Simply having female characters playing male roles, however temporarily, calls attention to the constructedness of the roles and thus raises the question of the inevitability of the sexual hierarchy.

With respect to the written Italian drama of the early sixteenth century, Giannetti observes that it often shows a society in which women are not merely objects of exchange in the patriarchy but rather one in which they succeed in satisfying their own sexual desires without regard for the economic and social concerns of their families. In the process they often live on their own for a time disguised as male, risking their chastity and honour, and demonstrating skills usually considered to belong only to men. Giannetti argues that “education, freedom of movement, and culture subtly triumphed over ‘nature’ in the imaginative vision of these comedies.”134

It is an easy matter to extend the comments of Howard and Giannetti beyond cross-dressing to all the roles played by women in Scala. One might argue, however, that what Giannetti sees is merely the unintended consequence of presenting women on stage, combined with the limitation to the outdoor setting, rather than the result of any “imaginative vision.” The extent to which Scala consciously participated in the lively debate in Italy at the time about the position of women in society cannot be known.135 The roles that the characters play and the complications in which they find themselves are largely necessitated by the fixed exterior setting. The realm of the possible for women was pushed by it. It allowed characters to engage in and succeed in situations that they would not otherwise have encountered. Even the love matches around which the actions pivot depend upon the exterior setting. It allowed upper-class young people an access to one another that they would not have had. The disguises in the scenarios, at one with the street setting, similarly provide characters with opportunities and actions in which they would otherwise not have engaged and require them to resourcefully confront situations that they would otherwise not have encountered. The women garner our sympathies in so doing, suffer no long-term ill effects of their actions, and, indeed, succeed in their objectives. In these ways the street setting was a fortuitous choice.

Moreover, if the ordering of the scenarios in the Scala collection is in any way chronological, the actresses and their roles to some extent seem to have grown into the use of the setting over time. Particularly in the earlier scenarios in the collection, a number of the young women merely serve as interchangeable marriage partners. In the later ones, many of their roles are more individuated. In Days 36 and 39 the female characters are the plot manipulators, albeit the goal of the female characters remains a marriage in which they will presumably remain faithful.

In the first part of this chapter I argued that the fixed street setting served commedia dell’arte as drama. In the second part I argued the extent to which the street setting was linked to the culture represented by the scenarios, that culture having been largely overlooked from a distance of four hundred years and in the focus on the analysis of the scenarios in terms of other theatre. By showing the relationship between the street setting and life, I have called into question, as in chapter 2, the assumption that little information about contemporary history and society can be gained from the pages of the Scala scenarios. In the third section I argued that there are theatrical and, from our perspective, socio-political advantages inherent in the limitation to the fixed street setting precisely because upper-class women would not realistically have appeared there. The setting obliged the female performer and her character to show themselves and to succeed in activities in which women were ordinarily not even allowed to engage, thus suggesting at least indirectly the potential of and possibility for all women. I have called for greater appreciation of the scenarios by attempting to shift the reader’s perspective on the scenarios to a perspective more aligned with that of their contemporary audience than with that previously provided by critics.

Having focused for two chapters on the relationships between the scenarios and life, I turn now to the self-conscious artfulness of scenario construction. As, in my discussions of character relationships, behaviour, and setting, I try to adapt my perspective to one that early modern audiences might well have had. I begin with a discussion of Scala’s imitation of models rather than of life.