The genre to which Isabella Astrologa belongs, commedia grave, was developed by playwrights in the latter half of the sixteenth century, notably by Sforza Oddi and Giambattista Della Porta. They borrowed from the romances and novelle of the period to show heroic intent, tragic potential, and exalted self-sacrifice. They began with an unhappy situation that was attributed to fortune and typically subjected their strong female heroines to various trials and adventures, throughout which they exhibited their constancy in love. Consistent with the relative seriousness of the scenario, the plot unravelling depends not on trickery but on the resourcefulness of an extremely capable woman; on benevolence; and, more than in other of the scenarios I have examined here, on Divine Providence, which provides escape from a near tragic end. Commedia grave plays, like this scenario, could feature upper-class characters generally within the purview of tragedy. In his second prologue to Prigione d’Amore (Love’s Prison), 1589, Sforza Oddi provided the rationale for this mixed genre: “In the bitterness of tears there is yet hidden the sweetness of delight; and I who wish in every way to give delight often make thus a most lovely mixture of both tears and laughter, and the bitterness of weeping makes more joyous the sweetness of laughter.”1

The same rationale seems to lie behind Isabella Astrologa. The tone is very different from that of the other scenarios whose actions I have reconstructed. More than any other of the scenarios in the collection it incorporates the business of a city, and one with international trade. It is necessarily set in its specified locale. In a number of the comedies in the latter part of the collection, as I have suggested, Scala seems more experimental than in those in the earlier part. At the same time that this scenario seems to be a considerable departure from those earlier in the collection, its structure is at times mechanical, motivated by dramatic convenience rather than by the story. Perhaps it was envisioned as a onetime extravaganza to be funded and performed, as Andrews suggests, before a princely court.2 It aligns that court, probably Spanish, with Divine Providence, judicial restraint, personal forgiveness, peace, and harmony.

Day 36

Isabella [the] Astrologer

COMEDY

Argument

In Naples a most noble gentleman from Spain named Lucio Cortesi held the office of the Regent of the Vicariate. He had a most noble daughter named Isabella with whom a gentleman, called Orazio Gentili, fell in love. It happened that her brother (whose name was Flavio) became aware of the courtship he was paying to his sister, therefore, overcome and moved by the greatness of Spain and by honour, he had thoughts of attacking him in the night and killing him; on the other side, the young Orazio had the same thought; and, encountering each other one night, they attacked each other; in this brawl Flavio was left wounded, [taken for] dead and thrown into the sea; by twist of fate he saved himself, and for shame he went off lost in the world, wandering for a long time. The aforementioned Orazio was caught by the [forces of the] law and condemned to death; and, while awaiting death, Isabella, daughter of the said Regent, who was in love with him, saved him with the help of the prison guard, and ordered him to prepare a frigate, with which she intended to escape with him. The unlucky lover went and, preparing everything, stayed in the frigate waiting for his woman to come with the guard, when, he was brought out to sea by a sudden storm; he was made a slave by pirates from the Barbary coast, and brought to Algiers; then hearing this news caused the grief-stricken lover to desperately board a ship, whose sails at that point were unfurling towards Alexandria of Egypt; having arrived there, she set about being a servant to a very great Arab philosopher and astrologer, who lived there; and because she was much inclined towards speculative matters, and [already] understood some of its principles, in not much time she learned a large part of the true astrology.

Flavio, after he found himself thrown into the sea by his enemy Orazio, supporting himself on top of a piece of wood, was driven by a sudden storm from the shore into the sea, and, found by pirates, he was made a slave, and he too was brought to Alexandria, and there was purchased from these same pirates by a very rich Alexandrian merchant. Flavio was liked by the daughter of the said Arab astrologer, who lived in a villa near that of his master; and such was their love that he, having secret relations with her, got her pregnant. It happened that the said merchant abruptly decided to board a ship from Alexandria going to Naples, to trade merchandise, and with him he brought Flavio, who was not able, as he [had] wished, to say goodbye to the young Turkish woman. The young woman seeing herself at that point abandoned and betrayed, spoke to the said Isabella, who was her friend – and from her [Isabella] hearing how, because of her master’s [the astrologer’s] death, she wanted to go to Italy, she entreated her to be so kind as to take her along. So agreed, having left and having arrived in Italy, after much time they get to Naples, [with] Isabella meanwhile, like a perfect astrologer, practising the art of astrology. Orazio arrived in Naples (and almost at the same time); [he was] captured by the galleys of Naples, while he went along with his master plundering the seas. For fear of the law, he said he was Turkish, nor did he wish for freedom. Finally, after many twists and turns of the tale, we reach a very fortunate and happy end.

The scenario’s long Argument is very complicated, and its overlong sentences and organization make it hard to follow. Part of the difficulty may be that, unlike in the scenarios where the Argument explains a sequential action, the Argument in this case tries to relate in linear fashion the two strands of action that happened simultaneously.

The Argument is also not altogether self-consistent. In the first paragraph Scala states that after Flavio attempted to murder Orazio in order to preserve the family honour and failed, for shame he went off, lost in the world and wandering about. In the second paragraph we are told, instead, that he was immediately found by pirates and enslaved.

While the time that passes in the scenario is very short, the time that passes in the Argument is long. Its various parts need to be narrated piecemeal by different characters at specified points in the scenario, and this suggests that the audience was interested in narrative form as well as in drama. Spavento’s windy tales in other scenarios, as well as other narratives to be supplied at indicated points in other scenarios, also testify to the audience’s interest in narrative. Commenting on the comedies of Aretino, Andrews observes, “It is a commonplace to say that Renaissance rhetoric made a large contribution in Renaissance dramaturgy: perhaps we should consider whether on some occasions a dramatic spectacle was really a disguised form of rhetoric.”3 In this scenario it is, but the spectacle is itself striking and provides a kind of grandeur and ceremony that would befit a presentation before dignitaries.

We do not know that the scenario was, in fact, ever presented. If it was, it had to have been funded by someone very wealthy and probably for a single occasion, perhaps in Naples, where it is set – a city, the scenario suggests, with which Scala had some familiarity. The scenario requires a very large number of extras (who would have to have been carefully rehearsed), their costumes, a singular set with a fine palace expressly rendered in perspective, and a suitably grand chair. This is one of the few scenarios in which, as in The Jealous Old Man, seating for characters is specified.

Naples was under direct Spanish rule from 1503 to 1707. It was not mandatory that the Regent of the Vicariate in Naples, the judicial official presiding over the main court in the kingdom, be Spanish, but in practice he likely was.4 Orazio’s attentions to the Regent’s daughter were out of bounds, not only for the usual reason that their courtship was not authorized by her father but also because, in this case, the woman is from the Spanish ruling class. Characteristically, Orazio is Italian and upper middle class. Flavio perceived that the honour of his family was threatened by Orazio’s secret courtship of his sister, not only because it lacked parental approval but also because marriage was regarded as a tool for the social advancement of the family and a means for the exchange of material resources. He must have had words with Orazio, words that led Orazio to believe that his honour too was threatened. The code of honour required that threats to honour be avenged.

After the murderous encounter between Orazio and Flavio, through many coincidences that Scala takes pains to explain, their fates run parallel: both Neapolitans have been separated from their true loves and both live under assumed names – one as a slave to an Alexandrian merchant; the other, first as a galley slave on a Barbary pirate ship, and then, pretending to be “Turkish,” in the galleys of Naples, part of the Spanish fleet that operated primarily out of Naples and Sicily. Flavio and Orazio were both picked up by galleys near the coast. The large number of men needed to outfit galleys required that they hug the coast in order to be able to stop repeatedly to take on water and food.5

In 1600, in Algiers, where Scala specified that Orazio was brought, there were thirty thousand to forty thousand Christian slaves, of whom perhaps a third to a half were Italian.6 Although the Barbary slavers ranged most widely and employed the most sophisticated of means, virtually everybody in the sixteenth-century Mediterranean was trying to enslave some other group. Christians took Muslims in numbers that were comparable to those of their Muslim counterparts.7 Muslim and sub-Saharan African slaves were common in southern Italy, the majority, like Christian slaves, being victims of piracy or warfare. Most male slaves served as rowers on galleys, along with convicts and a few others desperately in need of any form of employment. The powerful Spanish fleet required vast numbers of rowers. In the seventeenth century, between 20 and 30 per cent of the crews of the galleys of Spanish Italy were slaves. Female slaves, relatively less numerous, served as domestic help.8

When Orazio and Flavio return to Naples at the same time, coincidentally their loves, Isabella and Rabbya, also arrive. However, Isabella does not appear as she did when she was last in Naples; she has become an astrologer, having learned part of the true astrology (vera astrologia). Astrology, the means for determining the nature of the alliance between the events on earth and the stars, was seen as key to predicting fortune and was widely accepted. But much of astrology came in conflict with the Church. The belief that the destiny of human beings was irrevocably governed by the position or pattern of stars and planets was inconsistent with the doctrine of free will, the belief in Divine Providence, including the influence of Divine Grace, and the value of intercessory prayer. It left no way for the Church to teach moral responsibility, to promise eternal rewards, or to threaten eternal punishments.

Under Pope Pius IV, the Council of Trent in 1564 produced an index of banned books on astrology. More leniently, the papal bull of Sixtus V in 1586 repudiated all books on judicial astrology, that is, astrology that dealt with the influence of the stars and planets upon human events, declaring that God alone knew the future. The Church permitted only natural astrology, that is, opinions and natural observations written in the interest of navigation, agriculture, or medical art. In practice, the distinction between the two was not clear cut, and judicial astrology continued to penetrate deeply into the lives of most people, including some popes. As Lynn Thorndike observes, even the bull of 1586 inadvertently signalled that the force of the stars on humans was fact, by affirming that each human soul has a guardian angel to aid it against the stars.9 The more lenient Index librorum prohibitorum of 1596 allowed books containing judicial astrology by Christians, provided they were corrected or expurgated in so far as they claimed that contingent future events in human lives were certain, even in cases where the author denied that he was making any claim of certainty. Books on judicial astrology by pagan authors, the ones that would have been the source of Isabella’s learning, curiously enough, were permitted.10 Thus the Neapolitan dramatist Giambattista Della Porta in the preface to his tragedy Ulisse, 1614, ducked the prohibition with the following defence:

The present tragedy is performed by pagans. Therefore one finds in it the following words: fate, destiny, luck, fortune, the force and compulsion of the stars, gods, etc. This has been done to accord with their ancient customs and rites. The latter, however, according to the Catholic religion, are all folly since one must attribute all outcomes and events to our Blessed Lord, the supreme and universal cause.11

We cannot know how much Scala knew about changing Church doctrine. We know that in other of the scenarios he played it safe, steering wide of anything that might in any way offend the Church. In Day 26, Flaminia, disguised as a gypsy, pretends to read in Pedrolino’s palm what she has secretly overheard. Similarly, in Day 32, Pedrolino claims to identify Flavio by means of fortune telling, when in fact he has just overheard Flavio speak his own name.

In Isabella [the] Astrologer almost all of the knowledge that Isabella attributes to her special powers appears to be a function of her common sense. There seems to me a distinct possibility that a number of scenes in which she claims to have extraordinary knowledge are meant to be comic. She is never called upon to predict the future. The action of the play in no way depends upon her professed skills in astrology. The turns in the Argument and the scenario are determined by a number of forces that were given great credence in the sixteenth century: Fortune, Love (here that of Orazio, Isabella, and Flavio), and Reason, a force “more powerful than Fortune” (that of Pedrolino and, more importantly, of Isabella).12 The resolution depends upon forgiveness, grace, and finally on the force regarded as the most powerful: Divine Providence.

The translation provided here differs in significant respects from that of Andrews.13 In the cast of characters we have left untranslated the name Aguzzino, much as we have left untranslated the names given in the Argument, Cortesi, meaning kind and gracious, and Gentile, meaning courteous and kind. Aguzzino can mean either the overseer of galley slaves or a (usually cruel) jailer. Galere is here translated as “galley.” Only later, when galleys were no longer in use, did it come to mean “jail”; elsewhere (act 2, scene 12) Scala uses the word carcere for jail. As I show, information about the use of jails at the time and the story itself require that galere mean “galley.” Accordingly, and again because the logic of the story requires it, we take Capo, later referred to as Capitano di galera, to mean “Captain of the Galley.” In Andrews’s translation he is the governor of the prison. Andrews takes Capo della galera listed in the cast of characters and the guardino in the Argument to be one and the same. We do not. Our choices have depended on close reading of the scenario and, as will become clear, on cultural history.

The Regent is the only political personage to appear in a comic Scala scenario, and he is safely presented as a very dignified and reasonable person, a far remove from the laughable Capitano Spavento, who in other of the scenarios is the hungry and haughty Spaniard swaggering as a noble cavalier over the peninsula. The Spanish ship captain, who makes only a brief appearance, is all business. The merchant from Alexandria is no Pantalone but rather an upstanding and gracious man, not withstanding his keeping of Orazio as a slave and his desire for a prostitute. Neither would have been a source of disapproval. The aversion and animosity that mercantile activities prompted in the past, inviting performers to make Pantalone a figure of fun, are not in play. In 1585 Spain signed a peace treaty with the Ottoman Empire, but whether at war or at peace, the extensive and highly profitable trade between Italy and the Ottoman Empire continued, often on very friendly terms.14 An Alexandrian merchant would have been a familiar and desirable figure in Naples.

This is the only comic scenario in which Pantalone does not appear. Perhaps it is for this reason that Scala specifies that the role of Graziano can be played by Pantalone. Evidently either mask would do. At the lower end of the social spectrum, Scala represents the only pimp in his collection. There are also slaves. Altogether, it is clear that in this scenario Scala does not confine himself to imitating the actions of private citizens of moderate social rank, their servants, and children. Contrary to Aristotle’s dictum, the characters do not appear to be worse than those in ordinary life: Pedrolino is a loyal servant; Graziano has a serious role.

Four important new characters are created: a Spanish dignitary (the Regent), an Alexandrian merchant, the Turkish woman Rabbya, and the captain of the Spanish galley. This is one of Scala’s two comic scenarios in which a baby appears.

Isabella, very different from the Isabella in, say, The Fake Sorcerer, works to support herself and manipulates the plot. Arlecchino, in a minor role as a pimp, is an independent literate contractor.

The list of properties makes clear that Scala, at least for this scenario, envisioned scenery using perspective painting.

|

First Act |

|---|---|

1. AGUZZINO [SLAVES] [AMETT, SLAVE] |

comes with the galley slaves to get water from the well of the palace of the Regent, sends the slaves in to get water, and remains with Amett [who is really Orazio] sitting on top of two barrels; asks the slave why he sighs every time they come to that palace to get water and stays reluctantly. Amett tells him that in Algiers he had a friend, named Orazio, who was a slave because of Love. Several times he [the friend] had told him the story of his misfortune; here he tells all that had happened [to him], as is written in the argument of the fable, adding that he sighs out of pity for his friend. Aguzzino: that he remembers that case, which happened many years ago. Amett then tells how the said Orazio died. Aguzzino: that it would be good to give this news to the father of the one who had been killed by Orazio, because they would get a tip out of it; at that |

The entrance and then, in the next scene, the exit of a chorus of eight slaves in chains and carrying barrels provide an arresting frame for the long narration during which the speaking characters are seated and thus rather static. Visually striking entrances and exits substitute for dramatic action and, along with the narrations and seated figures, establish a measured ceremonial pace. Each of the first five scenes entails entrances and exits of either multiple slaves or servants. Remarkably, no action begins until scene 10 and then only in the tertiary plot. Urgent action only comes into play at the end of the second act.

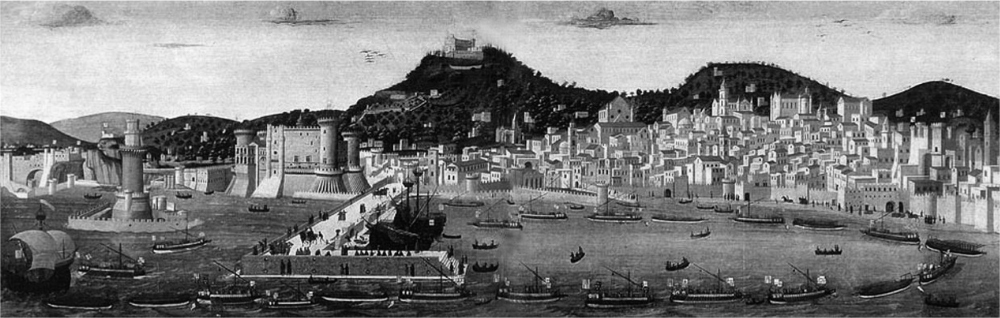

Maps of Naples from 1550 and 1572 show the urban area of Naples all very close to the shore. The bay would have been a presence from much of the town.15 An actual castle, Castel Nuovo, was very near the port (see figure 8.1).16 At the time Scala wrote, it served as an important military fortress, did not have the colonnade specified by Scala for the Regent’s palace, and would have been too vast (even without the pictorial exaggeration in figure 8.1) for the palace of the Regent, but its location may have been suggestive to Scala. It would have been a logical place for a galley of Naples, as part of the Spanish fleet harboured there and directly under Spanish control, to get water.17

In Roman drama, the entrance to the harbour and foreign parts was stage left, and the entrance to the city proper was stage right.18 It is impossible to know whether Scala was familiar with this convention and employed it here, but his scenarios do show that he carefully visualized offstage spaces and thus would have had some such means of defining them for the actors and the audience.

8.1 Tavola Strozzi, View of the City of Naples in Italy from the Sea, 1470 (depicting the naval victory of Alfonso V of Aragon over John of Anjou). Museo di San Martino, Naples. Public domain.

Orazio is enslaved by and as a result of Love. His determination to find Isabella, like hers to find him, is long-standing. He evidently is not enchained and has not been assigned the hard labour of the other galley slaves but is, rather, at liberty to sit and talk. Scala motivates his long exposition by Aguzzino’s query about his sighs. Given the small-town quality of life in even large Italian cities, and the facility with which gossip spread,19 Aguzzino would have known about the fight between Flavio and Orazio, about Orazio’s escape from the law, and about the storm that brought the frigate out to sea. Breaking up Orazio’s narration, Aguzzino can tell, reiterate, or enhance those parts of the story and make clear the relationship of Flavio to the Regent. His interest in the story, to “get a tip out of it,” promptly arrests the sadness of the tale and the tone of its delivery and shows that he does not realize that Amett is Orazio.

If the audience is not enabled to deduce or know in advance that Amett is Orazio, the scenario seems to me seriously diminished. The scenes that follow from Orazio’s story about his own death must be appreciated at the time of their performance and not just in retrospect, otherwise the audience can take no pleasure in his disguise and indeed would feel deceived by him and by Scala. What means Amett might use to convey the information that he is Orazio is not clear. We cannot rule out the possibility that at least this part of the Argument was provided in a prologue.

In the second half of the sixteenth century there was an increased interest in comedy that included stories of lost children, pirate raids, shipwrecks, abductions, the misfortunes of war, abandoned lovers, presumed deaths, and the exotic people discovered in the course of maritime exploration and commerce. Similar increasing interest in such misadventure and travel is revealed in Scala’s scenarios, and when, as here, the misadventures are central to the action, they tend to darken its tone.

2. SLAVES |

return with the barrels full of water, and all together with Aguzzino as guard they go to the galleys, away. |

|---|

The sad narration is long enough for the slaves to have filled the water barrels.

It seems unlikely that any of the men just having exited in chains, carrying barrels, could readily reappear as servants following a costume change, particularly because the space they would take up in exiting suggests that the Merchant and his entourage would enter from the opposite side of the stage.

That the Merchant, again in a sudden departure, intends to board a ship from Dubrovnik makes clear that the port of Naples was of enormous commercial and maritime importance20 and that Scala intended to represent it as such. The Merchant’s urgency suggests that there is urgency to the action although neither we nor Flavio (Memmii) know that Flavio’s love is in Naples and that in leaving Naples, he would be leaving her. The captain likely exits towards the ship, ostensibly to see to his departure and to allow the number of people in the next scene to enter from the city side, laden with goods.

The typical things from Naples that a merchant might seek as gifts included velvets, laces, braids, frills, trimmings, light fabrics, fine linens, and silk clothes.21 Memmii is a trusted slave who, having come from an upper-class family, can read and write.

In this narration, barely separated from the one that opened the scenario, the audience learns that Memmii is Flavio in disguise, alive and present in Naples. That he would logically experience internal conflict about being a slave in his native land where he is comfortably the son of a high-ranking dignitary makes the monologue more interesting than would mere exposition, and motivates it. We are set to anticipate the meeting of the mortal enemies, Orazio and Flavio.

It is difficult to determine whether or not the character addresses the audience directly. Apart from a single sentence at the end of act 2 in Day 37, Scala’s comic scenarios provide no clear evidence of direct address (see p. 276 note 59). Plautus used direct address; Terrence did not. Andrews demonstrates that in the learned comedy, which commedia dell’arte imitated, Donatus’s prohibition of direct address was not strictly followed.22

4. PEDROLINO [SERVANTS] |

buyer for the Regent, with servants loaded with stuff, he sends them into the palace, then he is interrogated by the slave and asked if the father of a certain Flavio, called Lucio Cortesi, [the] Regent, is alive, and if a sister of his [Flavio], named Isabella, lives. Pedrolino is surprised, he tells him he [the Regent] is alive, but that the sister ran away from Naples, nor have they ever been able to get news [of her]. The slave tells him that he had known Flavio in Alexandria, and that he is alive; at that |

|---|

Now comes another procession of men carrying things. At least in this instance there has clearly been time enough for the slaves, or some of them, to reappear here as servants, probably from the opposite side of the stage in order to represent more clearly the new characters. Pedrolino must identify the palace of the obviously wealthy Regent and his own role relative to the Regent. Having introduced Orazio and his story, and Flavio and his, the latter by means of a response to Flavio’s query, Scala now introduces the Regent and explains in yet another long narration the events that caused Isabella to leave the country. Flavio must surreptitiously be relieved that his father is alive and disturbed that his sister has run off.

5. MERCHANT [SERVANTS] |

arrives and, seeing Pedrolino speaking with his slave, he asks him what his profession is. Pedrolino: that he is a pimp. Merchant: that he find him a beautiful Spanish courtesan. Pedrolino promises. Merchant, away with Memmii and servants. Pedrolino stays, unsure whether he should tell the Regent about Flavio or not; at that |

|---|

In another scene with an entourage, the Merchant returns with his servants. Scala provides a comic break from the long, sad narrations. Pedrolino, in his only and little trick, misleads the Alexandrian merchant into thinking that he is a pimp. The Merchant wants the best of prostitutes, a courtesan, and a Spanish one at that. Nothing comes of this request, but Arlecchino and his business are introduced by means of it, and later another character does make use of Arlecchino’s services. Arlecchino turns out to be a character with whom a significant number of the characters interact, thus providing one of the means that make the actions cohere. Pedrolino’s uncertainty about whether to report to the Regent that Flavio is alive may tell us something about the Regent’s present state of mind regarding his son’s supposed death and lead us to anticipate his learning that he is alive.

6. ARLECCHINO |

professional pimp. Pedrolino asks him for the courtesan for the merchant. Arlecchino names a number of courtesans from different countries, having written them all down on a list, and [says] that when it gets late, he will give him a very beautiful one; on condition that Pedrolino get him permission from the Regent for him to go around at night without a light; so agreed, Pedrolino, in[to] the palace; Arlecchino, praising the art of the pimp, leaves. |

|---|

Conveniently, an actual procurer appears, presumably from his place of business, to establish it as such for the audience. His place of business would not have been distinguished from other houses. Dianne Ghirardo explains that

everything about both the activity [of prostitution] and its settings revealed constant and irresolvable contradictory impulses. At once shameful and endemic, officially unacceptable but a useful complement to the imperative of female chastity, prostitution was both an everyday activity that blended almost seamlessly with the rest of civic life and the most readily available scapegoat for a variety of social, economic, and cosmological ills.23

The procurer’s brothel, although inconspicuously intermixed with other dwellings, would have been located not far from the market or some other good business location, like the port.

One of the few successful activities for entrepreneurs in Spanish Naples was prostitution, owing particularly to the influx of Spanish troops and the destitution of the urban poor, although prostitutes frequently came from elsewhere in search of both work and anonymity. Thus, a list of prostitutes in Rome included names like Antonia Fiorentina, Fran-cesca Ferarese, and Narda Napolenta.24 Such names on Arlecchino’s list would have added to the actor’s comic turn. He might also have added prices as in the famed Catalogo di tutte le principale et più honorate cortigiane di Venezia, 1565.25 One contemporary observer commented that the freedom the prostitutes had to live in Naples meant that they were much in evidence, including in the best streets and squares, and had come from all over the world.26 Arlecchino very likely dealt in common prostitutes, however he may have referred to them.27

Prostitutes generally worked under male protectors.28 Arlecchino, the businessman, provides a list of goods of another sort than that the Merchant has asked Flavio to make. The repeated showing or mention of goods and services and the processions of their bearers give coherence to the scenario and suits the port city.

Arlecchino’s praise of the art of pandering may lend itself to song. Again, we do not know whether the speaker directly addresses the audience. His doing so would increase the lightness that his scene adds to the scenario. He leaves, presumably looking for new “stuff” (robbe) for his shop, as we see in scene 8.

7. ISABELLA [RABBYA] |

dressed in Syrian style, acting as an astrologer, with the Turkish woman her companion, and her son in swaddling clothes, narrates to her companion how she still carries within her the memory of her [Rabbya’s] father – most perfect astrologer among the Arabs, from whom she learned the art of astrology – and how before his death he made her an astronomical chart, telling her that he had learned [from it] that she would return to her native land and be happy and content, but that so far this has not yet come to pass; telling her [Rabbya] again the story of her misfortune, as it is written in the argument of the fable, and lastly she tells her how she too will be happy one day, although she [Rabbya] has never wanted to tell her who the father of the child was. Rabbya: that one day she will know; at that |

|---|

The male lovers have been introduced one at a time, one in a dialogue, one in a monologue. Scala now introduces the two women together along with Rabbya’s male child, the women’s relationship, and the story of Isabella’s misfortune. The narrations of extreme events have the added appeal of their narrators’ being in disguise as slaves or as an astrologer. The narrations have been punctuated by Aguzzino’s suggestion of an action at the end of scene 1, by Pedrolino’s pretending to be a pimp, by a real pimp, by processions of slaves and servants, and by a “Turkish” woman carrying a baby. These breaks in the narration of the primary action add activity and vividness to the city, and they add comedy to the otherwise, thus far, slow-moving scenario. Along with the narrations, and perhaps Rabbya’s withholding of information, to add a little suspense, these seem easily sufficient to hold an audience’s attention for the time being.

What the astrologer told Isabella and now what she tells Rabbya, namely, that each would be happy one day, may depend as much on faith and hope as on astrology. The promised happiness, as Isabella reminds us, has yet to come to pass. However, the playwright, the real fortune-teller, here reliably foretells that the sad predicaments thus far narrated will be resolved happily.

All the central players have now been introduced at least by name. A familiar return motif has providentially brought the four dispersed lovers to Naples at the same time. They have yet to meet. No major conflict has been introduced. The audience must strongly suspect that Rabbya is Flavio’s beloved and anticipate their meeting.

8. ARLECCHINO |

looking for new stuff for his shop, sees the women, he wants to lead them to the store of shame. They: that they are not of that sort. Isabella tells him that she is an astrologer, and, looking at him, by palmistry and by physiognomy tells him that he is a pimp, and that the galley and the gallows threaten him. Arlecchino wants to lead them into his house by force; at that |

|---|

Now in another comic interlude, suggesting the perils of women on their own, Arlecchino tries to lure them into his place of business, perhaps quite indirectly, in language full of double entendres. His manner will, nonetheless, betray him, and Isabella requires no palmistry or reading of physiognomy to know him for what he is. If she pretends to require such skills here, the effect is comic. This is the first display of the gumption of Isabella that is manifest in the Argument.

Isabella’s threat of a punishment of the galley for Arlecchino cannot be a reference to a prison sentence. Prisons only held people until their cases were decided. Cost-effectiveness suggested quick punishments: penances, fines, floggings, mutilation, time on the galleys, expulsion, or the gallows.29 Not only was time on the galleys a cost-effective punishment, but it also served the naval fleet and thus was a frequent punishment for serious and even petty crimes.30

The Spanish authorities taxed the earnings from prostitution, but as Scala’s scenario suggests, prostitution, though regarded as a necessary social evil, was increasingly viewed with opprobrium.31 Moreover, Arlecchino is found trying to force the women.

In the Argument, Isabella is said to have come from Egypt dressed in Syrian style. Here she says she comes from Syria. It was all “Turkish” to Scala because, at the time, the term was broadly used to refer to anyone who was Muslim or from the Ottoman Empire.

In this first meeting of any of the plot’s major constituents the benevolent Regent saves the women. He does not recognize his daughter, and she does not acknowledge him as her father. Contrary to any expectation that women should remain in the house, silent, with head bowed, Isabella lectures at length to a high-ranking man in a public place. Moreover, contrary to all belief that science, philosophy, and rhetoric were not appropriate topics for women, Isabella demonstrates her formidable knowledge of astrology. There were in fact some very learned women and even a very few female philosophers who wrote about astrology. Isabella’s outspoken mental ability was earlier a feature of the women in plays by the Academy of the Intronati, in which, Laura Giannetti observes, women, given the opportunity to study, were shown to be as competent as men.32 Their confident mental agility was excused by disguises and by the constancy in true love for which they undertook their risky ventures.33

Isabella’s identification of the Regent by name requires no astrology; he is her father and he has entered from her house. The Regent probably exits in one direction towards the Vicariate (located, actually, in Castel Capuano), and the servants, seeking Isabella, in the other.

We are introduced to another father and son, who perhaps enter from a third onstage building, and finally to a conflict, in a tertiary plot line, entailing a third set of lovers. Graziano points to the potential story parallel between Cintio and Orazio. We hear, or hear again, about the class and ethnic differences as well as the failure of the fathers to give their assent to the sought-after love matches. The cast list specifies that Graziano is a physician. Perhaps this is made clear here. Left alone, in another long monologue, Cintio does not resist his father’s admonitions as do sons in other Scala scenarios, but worries, rather, that they are appropriate, thus suggesting the dignity of Graziano’s role.

11. PEDROLINO |

aware of his love, consoles him, telling him he has a [piece of] good news to give him, but that he does not want to tell it if not in the presence of Flaminia; enters into the palace to tell her to come to the window, then returns; at that |

|---|

Pedrolino comes out onto the street from the palace. When he returns inside the palace, Cintio will have to fill the time with expression of his fears and hopes. Scala finds a reason to introduce Flaminia at this point because she does not appear again until the third act and because her response and Cintio’s response to Pedrolino’s idea make a highly emotional closing for the act.

Scala’s directions for the action are very explicit and include dialogue. Pedrolino, having found a way to use the information he has that Flavio is alive, no longer hesitates to have it provided. By means of it, Scala points towards a meeting between the Regent and Flavio and interweaves two plot lines. In Pedrolino’s characteristic interest in serving the young in their affairs of the heart – here Flaminia – he goes so far as to forgo any reward he might receive, by providing the information himself. Having seen Flavio, the audience knows that Pedrolino’s information that Flavio is alive is reliable; however, it seems impossible to the lovers. With weeping and rage, some tension is established finally at the very end of the first act.

|

Second Act |

|---|---|

1. REGENT [SERVANTS] |

returns from the Vicariate to go to the palace, asks the servants if they have found the Astrologer. They: that they have not; at that |

There is no indication that the barrels are used for seats after act 1, scene 1. At what point they have been removed is not clear, perhaps even by Aguzzino and Orazio at act 1, scene 2. In any case, they are unlikely to be present in this act.

We are reminded of where the Regent went at act 1, scene 9, and that when he left, he was seeking the astrologer in order to question her. Scala delays and builds suspense for this meeting with her. We do not know from where the servants appear.

2. AGUZZINO [AMETT] |

greets the Regent, giving him news that Orazio, who killed his son Flavio, has died in Algiers, [a] slave in chains. Amett confirms [this], and [tells] how he died at his [galley] bench. Regent: that they [should] return after the meal, that he will give them a very good tip, and goes inside the palace. Amett sighing, promises Aguzzino that he will have him earn some additional tips, and away they go. |

|---|

The overseer of the galley now comes to earn the reward that he had proposed at the end of act 1, scene 1. Orazio, still fearing punishment for having killed the son of the Regent (as he thinks), provides what is probably a gruesome tale of his own death on the galley bench. In contrast to this slave is the Regent, whose presence is enhanced by servants. The Regent goes into the palace with them. Orazio in his present state apparently has little hope in life but to generate further tips for Aguzzino. How he can do so is unclear; he has already provided the news that the Regent would most like to hear. Scala seems to want to add suspense and a nice exit line.

3. GRAZIANO [CINTIO] |

hears from Cintio what Pedrolino has ordered him to tell the Regent. Graziano: that he should not trust him, and he [Cinzio] adds that Pedrolino is the go-between in his affair with Flaminia and how she does not trust anyone else but him; at that |

|---|

The audience is reminded of this tertiary plot, but it is not further advanced by this scene except in so far as Cintio seems to be trying to persuade himself and his father of the trustworthiness of Pedrolino and therefore of his claim that Flavio is alive, and that he should act upon that claim. The scene prepares for the next one in which Graziano hears Pedrolino’s assurance directly from him.

4. PEDROLINO |

who is going [around] looking for the Astrologer, sees Graziano, to whom he says that Flaminia, his mistress, is in love with his son Cintio, and that she wants no other husband but him, and he asks him [Cintio] if he has spoken to the Regent, and told him all that he had been ordered to. Cintio: that he has not. Pedrolino urges him again. Cintio, goes into the palace to tell him. Graziano, away. Pedrolino says: “Where the devil will I find this Astrologer?” |

|---|

The search for the Astrologer is now becoming a running joke and conveniently provides Pedrolino with an opportunity to further persuade Cintio to action, which now he takes, leaving us to anticipate conflict. Graziano, whose resistance to that action has evidently been lessened by the words of Cintio in scene 3 and now by those of Pedrolino, seems not to protest it further; he exits.

Pedrolino functions primarily as a loyal servant. His role as plot manipulator and mezzano, or go-between, is slight. Commenting on the work of Sforza Oddi, Robert Leslie notes that the reduction of the role of the go-between in plot manipulation is characteristic of commedia grave34 because the great force is Divine Providence.

5. ISABELLA |

immediately says: “I am here.” Pedrolino: that his master the Regent wants to converse with her again, and wants to know from her if a certain Orazio is alive or not, having been told by one Aguzzino and by a slave that he died in Algiers. Isabella: that for now she cannot come, but that in one hour she will go to the Regent and will be able to tell him everything. Pedrolino gives her two scudi, entreating her to tell him if one Flavio, son of the Regent, is alive or dead, because a certain Alexandrian Merchant has told him that Flavio is alive. She is amazed by the news and promises Pedrolino that she will be able to tell him the truth. Pedrolino, away. Isabella, remaining alone, laments her fortune, because the truths of astrology show themselves to be uncertain. By the power of the stars she has always known Orazio to be alive; she resolves to converse with Aguzzino, with the slave and with the Alexandrian Merchant, one and all, to learn the truth of what was said by Pedrolino, whom she recognized very well, and away. |

|---|

Isabella, like the pimp before her, appears fortuitously. Pedrolino’s searching everywhere for her builds our anticipation for her entrance and for her powers and serves to herald her. The Regent seeks her to learn whether Orazio is alive. Owing to the extreme difficulty in getting a letter through, spell casters and charm chanters were frequently asked whether those missing were alive, slave, free, or turned Turk (that is, converted to Islam).35 Isabella’s surprise upon hearing that Flavio is alive must be hidden from Pedrolino because she would ostensibly have no knowledge of who he is. Her response to the news, however, must be evident to the audience.

His search complete, Pedrolino presumably returns to the palace. Significantly, Isabella is not called upon to predict the future but only to state what is in the present. The truths of astrology are uncertain; Isabella will ask around to learn the answers to the questions put to her. Her meeting with the Regent is delayed, and the suspense is increased.

6. ALEXANDRIAN MERCHANT [MEMMII, SLAVE] [SERVANTS] |

asks his slave the reason for his sadness, and why he has not had lunch. Slave says he is not feeling too well; at that |

|---|

The scene recalls act 1, scene 1, in which, at Aguzzino’s urging, Orazio explains why he sighs. It forebodes Flavio’s fall to the ground in the next scene and partially motivates it; Orazio has had no lunch and feels ill. The servants need to be onstage in this scene only to carry Flavio off after his collapse in the next scene.

7. RABBYA, TURKISH [WOMAN] |

with her little son in her arms. Merchant, seeing her dressed in the Turkish [style], asks her about herself. She says she is a native of Alexandria and the daughter of an Arab astrologer and Muslim named Amoratt, and how her father when he was alive kept her in a villa of his not far from the city; the slave looks at her, and, as if filled with wonder, he falls to the ground unconscious. Merchant is surprised and has him taken away to the ship, and leaves with them. Rabbya, having recognized her lover, complains of his betrayal of her;* at that |

|---|

The lovers have each had a scene in which to explain their backgrounds. Rabbya had exchanged her honour / material good for the honour/word of Flavio. The transaction was inherently unequal. In giving away her honour, she gave away the one asset essential to her contracting a respectable marriage. A young woman who succumbed to a man promising marriage often found herself as abandoned as Rabbya feels here.36 The lovers have miraculously found one another, but there is no interaction.

Isabella presumably returns from the search she conducted to learn whether Flavio and Orazio are alive. There is no reason, except dramatic, for Rabbya to keep denying Isabella her full story. The departure of Rabbya with her baby to rest serves to allow Isabella to be onstage alone. It is unclear whether Isabella has learned that Orazio and Flavio are alive by way of diagrams as she says or whether she expresses her hope and faith. The audience already knows that Flavio is alive.

It is Orazio who is about to be in grave danger. Scala seems to have provided Flavio’s name in error. Orazio’s impending danger is a new potential plot complication arising just when a resolution seems to be in the offing. It is the one clear prediction that Isabella makes in the scenario and then only to herself.

9. AGUZZINO [AMETT] |

with Amett, the slave, on their way to the Regent for the tip. Isabella immediately withdraws; then he [Aguzzino] tells him they are too early, and that he wants to go into the pimp Arlecchino’s house to stay [for a while] and that he [Amett] wait for him at the door; at that |

|---|

Scala further delays the meeting of Isabella with the Regent and with Orazio. He reintroduces Arlecchino and his whorehouse and brings them together now with Aguzzino and Orazio. It is Aguzzino, not the higher ranking, more respected Merchant, whom we see actually making use of Arlecchino’s services. Aguzzino likely knocks on Arlecchino’s door. The audience must be made aware that Isabella, who has withdrawn, sees Orazio. At what point she recognizes him is not clear. She must indicate to the audience that she has.

10. ARLECCHINO |

[comes] out, leads Aguzzino into the house. Amett remains at the door to wait for him; at that |

|---|

There is opportunity here for a brief comic scene involving Aguzzino’s sexual interest and Arlecchino’s promise of untold pleasures. Arlecchino serves to get Aguzzino offstage for the next scene.

It requires no astrology for Isabella to know that Orazio is lying about his death because she recognizes him. She knows from having overheard his conversation with Aguzzino at act 2, scene 9, that the two of them were attempting to earn a tip from the Regent by reporting that death. In pretending to be dead, Orazio, from Isabella’s perspective, effectively denies his relationship with her. Thus, in despair and anger, she declares herself dead. The two women, both feeling betrayed, have now recognized their lovers, the most important of the women last. Their lovers have yet to recognize them. The audience will know that Orazio’s response to hearing that she is dead proves his faithfulness and devotion to her. Her despair and anger seem to prevent her from understanding this until too late.

12. REGENT [SERVANTS] [CINTIO] |

arrives; Orazio immediately kneels down, reveals who he is and his [real] name [that] he had concealed by using the name Amett and by [pretending to be] Turkish; [he was] nabbed by the galleys of Naples. He says that, because he has heard that his Isabella is dead, he resolves that he too will end his life. Regent is surprised by Orazio’s steadfastness and has him taken to the prison. Regent remains with Cintio, talking about his [Orazio’s] action; at that |

|---|

The Regent comes out of his palace with Cintio and servants. The servants have rather awkwardly to be present to lead Orazio away. Isabella must have withdrawn again because the Regent, who has been in search of her since act 1, scene 9, never so much as acknowledges her. But she is clearly present onstage, reacting to Orazio’s plight. It is not obvious where she might exit.

The potential conflict between Cintio and the Regent seems to have been resolved successfully offstage. With the news that Flavio is alive, the Regent has evidently been willing to overlook any possible obstacles to his daughter Flaminia’s marriage and has given his assent to it. Both he and Cintio are pleased. Without complication, the tertiary plot is all but resolved.

Orazio by contrast, believing Isabella to be dead, finds no reason to go on living and, on his knees before the Regent, gives himself up as Flavio’s murderer. The kneeling pattern will be repeated with Flavio on his knees before Rabbya, Pedrolino on his knees before Isabella, and Isabella on her knees before the Regent. The scenario is marked by the humility of its characters.

Orazio is taken off to jail to await trial.37 The scene between Cintio and the Regent reveals their new relationship and reiterates the story of the presumed murder and of Orazio’s escape from jail, aided by Isabella and the prison guard, whom we never see. Enough time is passed by their conversation to make plausible the return of the servants and the police who meanwhile have been wholly moved by Orazio’s tale of all that he suffered for true love.

13. SERVANTS [COPS] |

bring with them many cops and tell the Regent how Orazio has made all those who have heard his case weep; at that |

|---|

Men could weep openly in public on certain occasions, as we know, without seeming unmanly.

14. AGUZZINO [ARLECCHINO] |

arrives; Regent has Aguzzino taken prisoner. Arlecchino wants to defend him, cops take Arlecchino prisoner too, and the second act ends. |

|---|

The Regent is perturbed, having just learned that Orazio is alive, and must presume that Aguzzino has been lying about Orazio’s death and has been knowingly harbouring the criminal all the while. On this account, Aguzzino is taken prisoner (prigione). Arlecchino may be arrested for obstructing justice. Prostitution, as I said, was a legal activity, one in which the Regent already knew that Arlecchino was involved.

The second act ends with three men being jailed prior to their sentencing. Given the nature of his supposed crime, the sentence for Orazio is likely to be execution.

|

Third Act |

|---|---|

1. ISABELLA |

mad at herself for not having revealed herself to him [Orazio], having seen his love and his faith [to be] still pure and intact, and having suffered at seeing him be taken prisoner; goes about thinking of various ways to free him, or to die with him; at that |

Isabella reminds us of what happened at the grievous end of the second act. She reacted too late to Orazio’s response to her declaration of her death. As with Orazio’s prior arrest (the one narrated in the Argument), she seeks to free him. Failing any present rescue, without him she is as willing to die as he is.

2. RABBYA, TURKISH [WOMAN] |

with her child, unsettled by what she has seen of her lover the slave, sees Isabella, who again entreats her to tell her who it was who took her honour. She: that she does not know his Christian name, telling her in brief how that slave was the slave of an Alexandrian merchant, who had a villa near that of her father of blessed memory, and how he so knew just what to do and just what to say, that he went [to bed] with her, with the promise of taking her as wife, [once] she became a Christian, and how he went away from Alexandria with his master; and she has never seen him again, nor does she know where he may be. Isabella consoles her again, telling her that she has seen by way of her art how she will soon be happy; at that |

|---|

This narration further reminds us of events in the second act. Finally our strong suspicion that Flavio is the father of Rabbya’s child is confirmed, and the details of their relationship are supplied. Here, as in several of Scala’s scenarios, it is conversion to Christianity, not ethnic difference, that matters. Isabella, while herself very unhappy, reassures Rabbya that she will soon be happy. Flavio, in his devotion to Rabbya, is, we know, disguised and a slave. We deduce that Flavio, alone empowered to restore Rabbya’s honour, will do so by marrying her.38

Again, an entrance is motivated by a search for the astrologer, about whom everything seems to revolve. Evidently, Flavio speaks in an aside about his intention to find her: in order to make Rabbya’s immediate confrontation of him plausible, she must see him before he sees her. During their interchange Isabella quickly conceives of an ambitious plan. She thinks of a way to resolve all their problems, not as an astrologer, but as the daughter of the Regent and the sister of Flavio. It remains to be shown who might be the second person Isabella wants forgiven.

4. GRAZIANO [CINTIO] |

hears from Cintio his son how Orazio, the one who killed Flavio the son of the Regent, is a prisoner for [taking] his life, and that the following morning they will kill him, as he has already been tried and everything, and how the Regent has promised him Flaminia, since he brings him news that Flavio is alive; at that |

|---|

In the small world of the neighbourhood, news travels fast. Cintio makes a point of explaining for the audience’s sake the speed with which Orazio has been tried and sentenced and is to be executed. The whole action, after so many delays, now rushes towards a crisis.

5. PEDROLINO |

in despair since he can find neither the Alexandrian merchant and slave, nor the Astrologer, and he [says] how they want to kill Orazio; at that |

|---|

Scala repeats the refrain of Pedrolino’s not being able to find the astrologer and of her arriving pat to the occasion in the next scene. It is not clear why Pedrolino seeks the merchant and his slave except that Scala needs to bring all the characters back onstage for the ending.

6. ISABELLA |

arrives; Pedrolino immediately entreats her on his knees to free Orazio from death with her art (if she can), and moreover to tell him, as she had promised him, if Flavio is alive or dead. She consoles them all, saying affirmatively Flavio is alive, and that she wants to converse at length with the Regent. Cintio, cheerful, says that the hour of the public audience is near; at that |

|---|

Isabella has no need of astrology to know that Flavio is alive; she has just seen him.

There is no indication of any exit for Cintio and Graziano after act 3, scene 4, or of their participation in this scene, and their presence onstage, presumably to begin to mass the characters for the scenario’s conclusion, is awkward.

7. REGENT [CAPTAIN OF THE GALLEY] [SERVANTS] |

with the Captain of the galley, asks what he wants. The Captain tells him he wants his Aguzzino, and his slave Amett, who are imprisoned – it being [the case] that his Most Illustrious Lordship does not have power over the men of his galley, and galley of his King of Spain. Regent reveals to him that Amett is not Turkish, but is that Orazio who killed Flavio his son, who kept himself [hidden] under the Turkish name so as not to be recognized, but that he will give him back Aguzzino. The Captain agrees; at that |

|---|

Evidently the Regent is now seated for his public audience.39 It is not certain when the chair might have been brought on, perhaps by the servants at this point.

This is the first appearance of the Captain. His relationship with the Regent is cordial.40

8. ISABELLA |

presents herself before the Regent, telling him she has come [before him] to make him happy and console him, although at first sight it will all seem to him to be the opposite. Regent receives her gladly. Isabella entreats the Regent to have that Orazio who killed his son Flavio brought before him. Regent sends for Orazio. Pedrolino and the servants go away for Orazio. While they are going to get Orazio, Isabella makes a speech on morals, showing that all of the trials that come to us from the heavens are for the greater happiness of humankind; at that |

|---|

Isabella’s speech makes plausible the passage of time that is required to fetch Orazio. More important, it makes clear that all the tribulations have been the working out of a heavenly plan for human happiness. Louise George Clubb notes that in play after play of the commedia grave “it is expressly stated that the seeming chaos and confusion of the intrigue are in fact part of a plan above change, a divine pattern implicitly or explicitly Christian, guiding the characters … to perfect order.” In the second prologue to his Prigione d’amore Sforza Oddi explains that commedia grave teaches people, especially lovers, not to despair, because even in their darkest confusion the pattern for their happiness is taking shape.41 Their fidelity seems to deserve divine intervention. We await Isabella’s plan.

9. ALEXANDRIAN MERCHANT [MEMMII, SLAVE] [SERVANTS] |

having been informed of everything by Flavio, his slave, bows before the Regent, telling him that, when he has finished his business, he wishes to talk to him about something very important; at that |

|---|

The audience already knows all that the merchant has learned, but for the merchant’s role in act 3, scene 11, it must be clear that he knows. The merchant is discreet and respectful. We await his important disclosure.

10. RABBYA |

with her child in her arms, bows before the Regent, saying she is appearing before him seeking justice; at that |

|---|

Rabbya’s honour is at stake.

Now for the first time Orazio appears as a prisoner, bound. By having moved back the time of his execution, the Regent intensifies the crisis and serves to confine the action to within twenty-four hours. The lost son, presumed dead, has been found. That Rabbya has borne a son rather than a daughter makes her, as well as her child, more acceptable. Perhaps even more important is the fact that Rabbya is the daughter of a well-respected and influential man. Isabella has resolved the secondary plot.

For Flaminia, Isabella will have to identify her brother, whom she has not seen for a long time, and his wife and their child, about whose existence she has been unaware. In a quick ceremony of hand-holding, Flaminia and Cintio are espoused. Scala provides the words that Isabella now addresses to Flavio, “A voi sta di fare la seconda grazia, di perdonare alla seconda persona, et inoltre farle perdonare al padre,” presumably because of the importance of their being spoken just so; at the beginning of the sentence we still do not who the person to be forgiven is and must be surprised when, a little later in the sentence, the person is identified as female and, finally, as none other than herself. Just as Pedrolino often sums up the action of a scenario, including his role in it, so Isabella’s summary of all that she said and did leaves no doubt as to her centrality in the action and allows the audience the pleasure of reliving the action. Having just learned that his son is alive, having satisfactorily married off one of his daughters, and having been reunited with his son, the Regent (in the last of the scenario’s weeping, this time for joy) is in a forgiving mood and willingly gives Isabella to Orazio. Following a series of linked revelations, the whole family is reunited, and Orazio is accepted into it. The last and most important of the plots comes to a happy end. Quite surprisingly, having learned about Isabella’s great capabilities, Orazio values her more. But then, again, she did all that she did out of love for him.

As usual, there is one last small matter to resolve. The merchant, as charitable as is the Regent, forgoes the remuneration that might make up for Flavio’s original purchase price. The gifts for the Pasha that Flavio will provide are more than financial recompense; they will serve as proof of the Merchant’s personal contacts in Naples and of his elevated status there.42 Moreover, the goodwill offering to the Pasha will facilitate trade between the two empires.

13. AGUZZINO ARLECCHINO |

thank the Regent, |

|---|

The tag ending prolongs even more the great grace and joy of the conclusion that makes up for all that has gone before.