“Back then, Saturday was a night where no one was dominating. So the way that Brandon looked at it was that we could dominate if we found the right shows. He thought that the reason the HUT [households using television] level was down on Saturday was because nothing good was on.”

—GARTH ANCIER,

former head of current comedy at NBC:

Saturday Night Dead

![]()

ON ITS SEPTEMBER 14, 1985 debut, The Golden Girls earned golden ratings—and did so on a night where successful sitcoms have been rarer than platinum. Although Saturday night had once been home to CBS’s classic 1970s comedies—The Mary Tyler Moore Show, The Bob Newhart Show, All in the Family, and The Carol Burnett Show—the powerhouse programs had since been shifted to shore up the network’s other flagging nights. By 1985, Saturday had been all but abandoned. So when they heard that their promising new show was to air Saturdays at 9:00 p.m., the producers of The Golden Girls feared the worst.

But NBC had research to justify the bold decision. After all, the show’s presumed target audience—the older set—is often the only group home during prime weekend partying hours. Through testing, the network had learned something else: beyond anyone’s prediction, the pilot showed just as much appeal to just about all other age groups, too, including young adults, teens—even kids. Test audiences predicted that The Golden Girls would be an across-the-board hit. And with a hit early enough on Saturday night, NBC could draw people over fifty as they settled in for the night with the kids and grandkids, as well as those between eighteen and forty-nine before they decided which movie to rent or club to attend. And hopefully, the network could keep them around through the 1:00 a.m. end of Saturday Night Live.

Premiering just before the rise of cable TV, The Golden Girls became one of the last of the old-school broadcast network hits. With little Saturday night competition, the Girls routinely drew a thirty-plus “share,” meaning that 30 percent or more of the television-viewing audience was tuned in to the show; producers of today’s shows are ecstatic if they draw a share in the double digits. In all parts of the United States—red states and blue—The Golden Girls was a watercooler hit, unifying people of varying demographics and geographics if only for a half hour every Saturday.

Golden Appeal: Why People Love The Golden Girls

![]()

EVER SINCE THE Golden Girls went off the air in 1992, Saturday night has been abandoned again. The broadcast networks have once again hung the GONE FISHIN’ sign, airing no original scripted programming. But for so many of us who remember the show fondly today, The Golden Girls ushered in a comedy tradition, a comfortable world of funny grandmas and cheesecake to snuggle into on a Saturday night. Harkening back to the wholesome early days of TV, here was a show about grandparents you could watch with your grandparents. It aired on a night when bedtimes were relaxed and extended families might be together. It was witty enough for adults, while research showed that kids related to brash little Sophia.

For generations X and Y, Blanche, Dorothy, Rose, and Sophia became regular babysitters, seeing kids and young teens through Saturday nights at home while parents and older siblings might be out on dates; thirty years later for those grown-up kids, reruns on cable carry an air of nostalgia. For older viewers, The Golden Girls was the rare network show centered on relatable women “of a certain age,” bringing dignity and visibility to an otherwise-ignored bracket.

And right from its start, The Golden Girls was a watershed show for the LGBT community as well. Just as gay people often build surrogate families of their friends, the Girls choose to be together, even to the point of eschewing contact with their biological relatives. Instead of hanging out with kids who would treat them like helpless old ladies, they’ve built the fantasy family any fan would yearn for, founded on the acceptance for which so many gay and lesbian viewers yearn.

“I feel that The Golden Girls is the granddaddy—or grandmammy—of all female ensemble shows, and that’s because of the purity with which Susan created it. She took the three qualities that make up human beings and devised a character around each, of course with additional flourishes. If you consider Sophia off to the side and look at the other three, Dorothy is the intellectual, Rose the emotional, and Blanche the physical. It was so beautifully constructed that their points of view were always so different. And you knew how they were going to react in any given situation.”

—MARC CHERRY, writer

But the big draw for viewers of all ages was always the show’s impeccable writing. Working from a template designed by the revered Susan Harris, the show deftly managed a delicate balance of compelling, moving storytelling with razor-sharp jokes. As the only show on the air with such mature leads, The Golden Girls had the advantage of “owning” certain subject areas—and it mined them brilliantly for every vein of their inherent humor. What other show could bring four old ladies to a nudist colony—and wring a laugh out of their every cringe? Or have them arrested as Miami’s unlikeliest hookers? As it packed on the clever wordplay and double entendre, The Golden Girls far surpassed the IQ level of its 1980s peers and enticed veteran comedy writers and talented newcomers to join its writing staff. By the end of its run, the show had become a training ground for some of today’s hottest writer/creators, including Mitchell Hurwitz of Arrested Development, Marc Cherry of Desperate Housewives and Devious Maids, and Christopher Lloyd, one of the executive producers of Frasier and co-creator of Modern Family.

The Power of Four

![]()

THE GOLDEN GIRLS defined a generation’s view of older women, and single-handedly resurrected comedy during prime time on Saturday night. But perhaps the show’s most lasting innovation is the comedy formula it pioneered. Call it the Golden Rule of Four.

“Four points on a compass,” as Betty White aptly describes them, the characters of Dorothy, Blanche, Rose, and Sophia match up to four classic comedic types: respectively, the Brain, the Slut, the Ditz, and the Big Mouth. Comedy duos are a classic tradition, but a completely different animal. And while it’s certainly true that three women can work, especially in film—think 9 to 5—having three lead characters in a sitcom might leave one character having to carry the B plot on her own.

But four leaves us with infinite possibilities. Rose takes Dorothy’s night-school class in order to earn her diploma, while Blanche and Sophia compete for a suave Latin lover. Or Blanche and Rose try out for the road show of Cats while Dorothy tries to prove that her mother is faking her injury.

Having popularized the Golden Rule of Four,1 The Golden Girls is the thematic ancestor of many shows that followed. Only one year after the Girls’ premiere, along came the Southern version (Designing Women), followed in the 1990s by the black version (Living Single) and the urban version (Sex and the City). In recent years, the formula has shown a resurgence in popularity, spawning a suburban version (Desperate Housewives), a middle-aged version (Hot in Cleveland), a Latina version (Devious Maids), and, inevitably, more than one gay version (Noah’s Arc and Looking).

In Designing Women, which launched in 1986, vain Southern beauty queen Suzanne Sugarbaker would certainly sense sisterhood with Blanche. And apart from the difference in accents, Charlene Frazier’s hometown of Poplar Bluff, Missouri, could easily be mistaken for Rose’s birthplace of St. Olaf, Minnesota. Suzanne’s older sister, Julia, is clearly the Dorothy of the group—smart, opinionated, and prone to speak her mind. Only Annie Potts’s character of Mary Jo Shively is no easy match to a Golden Girl, perhaps because at the start, Mary Jo was the show’s least defined character. Over seven seasons, Mary Jo grew from a sheltered, naïve Rose-type into essentially a mini Julia, another Dorothy. So it’s no surprise that after his initial appearance in an early first-season episode (and also after actor Meshach Taylor’s small role in the Golden Girls pilot), Designing Women quickly promoted African-American delivery man Anthony Bouvier to regular status; like Sophia, he provides needed commentary from an outsider’s perspective (this time due to race and gender rather than age).

“There were so many pop culture references in The Golden Girls—and when you look back, many of them don’t hold up. But that also gave the writers opportunity to constantly be dogging Designing Women, putting in jokes to bash that show. I remember one example, from the fourth season, in the episode ‘Stan Takes a Wife.’ As Sophia is in a hospital bed, recovering from pneumonia, she tells the Girls, ‘I survived war, disease—and two seasons of Designing Women!’”

—RICK COPP, writer

Starting in 1993 on Fox, Living Single was almost a direct copy of The Golden Girls—and in fact, as Golden Girls writer Kevin Abbott explains, the show’s creator, Yvette Lee Bowser, even asked him for a copy of the Golden Girls pilot script to use as a template. Living Single’s characters of Khadijah and Synclaire James and Regine Hunter fit perfectly into the molds established by Dorothy, Rose, and Blanche, respectively. Again, only the Sophia role seems hard to fill, perhaps because when creating a show about young black women, there’s no obvious parallel for an old lady. But Erika Alexander’s character, Maxine Shaw, comes pretty close; in her flirtatious banter with upstairs neighbor Kyle, she can be the most outrageous and outspoken of the four friends.

In HBO’s hit Sex and the City, it’s obvious which of the characters is “the slut” and which one is a little bit naïve. And while both Miranda Hobbes and Carrie Bradshaw have moments of Dorothy-like cynicism, it’s Miranda who is the true master of the form. Although not a perfect fit in the Sophia role, obviously younger and sexier Carrie does share some of the old woman’s characteristics; in diner scenes (the show’s equivalent of cheesecake scenes) Carrie is often the character to sum up the situation, even at her friends’ expense. And just as Sophia recaps her roommates’ problems with pithy one-liners, Carrie literally narrates the travails of her friends, typing them on her laptop screen.

Inevitably, in 2005 came the first gay take on the formula, Logo’s Noah’s Arc. “I didn’t set out to make a Golden Girls,” says the show’s creator, Patrik-Ian Polk. For one thing, instead of a multicamera sitcom about women, Noah’s Arc was a single-camera, serialized drama about men. “But I did want to do a show about four black gay men, and so there are obvious parallels” to the Girls with his characters: sweet, naïve Noah, sexually voracious Ricky, sarcastic Chance, and outrageous Alex. “There were times when we’d have a funnier scene coming up with the four guys together, and I would say to them, ‘Think of this as a real Golden Girls–type scene.’ And they’d immediately get it.”

In 1990, during the Golden Girls’ run, one of the show’s writer/producers, Gail Parent, landed her co-creation Babes at Fox; but the sitcom about three overweight sisters and their elderly neighbor in a Manhattan apartment building was canceled after a single season. Ultimately it would be Gail’s fellow Golden Girls writer Marc Cherry who would find the greatest success by tapping into the power of the Rule of Four. Having tinkered with the formula in 1994 by creating The Five Mrs. Buchanans for CBS, Marc brought Desperate Housewives to ABC a decade later, while acknowledging his debt to the four ladies from Miami. “Blanche was my favorite character to write for,” he remembers. “Because the character was so selfish and vain and self-obsessed, and yet you still liked her.” Marc admits, “There were a lot of traces of Blanche Devereaux in Gabrielle Solis. It’s totally a credit to the actor. Like Rue McClanahan, Eva Longoria is one of those actors who is able to be likable when she is doing some unlikable things.”

Otherwise, though, Marc says that although his training comes from The Golden Girls, the construction of Desperate Housewives was more akin to that of one of its older siblings under the Golden Rule of Four, Sex and the City. Thus, his Lynette Scavo equaled Miranda, Bree Van De Kamp was Charlotte, and lead character Susan Mayer was akin to lead character Carrie. In creating Susan, “I chose to make the romantic character the show’s anchor instead of the common-sense one, as was done on The Golden Girls,” Marc explains. “Susan Harris’s paradigm was so successful—and indeed, Linda Bloodworth-Thomason copied it on Designing Women—that I just chose to emulate something else.”

In 2013, Marc gave the formula yet another twist in creating his follow-up series, Devious Maids. It’s easy to see parallels to Rose in naïve, good-hearted Rosie, and to Blanche in sexy and self-centered Carmen. And while the educated, intellectual Marisol has obvious similarities to Dorothy, Marc points out that “the tart-tongued part of Dorothy you will find in Zoila’s mouth.” In creating his Devious characters, he says, “I kind of took Dorothy and split her up.”

As Marc explains, “due to her youth and inexperience” there’s no obvious singular Golden antecedent for Devious’ fifth maid, Valentina; she has the naïveté of Rose, she’s a daughter like Dorothy, and as one set apart by age, she could even be seen as a twenty-first-century Sophia. But Marc does acknowledge the Girls as an influence when he was conceiving the character. In speaking with real domestic workers in Beverly Hills, he reveals, “I discovered that it was not uncommon for there to be two members of one family working in a home. And because I remembered the mileage we always got from having Sophia and Dorothy in the same household, I knew how effective it would be to again have a mother/daughter connection in this new female ensemble show.”

By 2012, viewers were ready for a foursome from a whole new generation, and HBO’s Girls was born. Although the show’s creator and star, Lena Dunham, didn’t base her Girls directly on the Girls from Miami, she does see at least one obvious parallel: “I think we can all agree that [Jessa] is Blanche.” As the show’s executive producer Bruce Eric Kaplan further explains, Lena’s creations do descend from Sophia, Dorothy, Rose, and Blanche—albeit indirectly. Addressing head-on the inevitable comparisons to its HBO ancestor Sex and the City, Girls’ pilot featured not only a discussion of Carrie and company, but also a poster of the iconic nineties series on Shoshanna’s bedroom wall. “We have a very clear connection to Sex and the City,” Bruce explains. “Girls is an update of Sex and the City, much as Sex and the City was so clearly a modernist version of The Golden Girls. So I guess Girls’ link to The Golden Girls is sort of transitive.” Thus, he adds, Girls lead character Hannah Horvath may be more direct a legacy of her more immediate predecessor Carrie Bradshaw than she is of Dorothy or Sophia. But he agrees the connection is there.

Most recently, HBO debuted another fab foursome with Looking, a San Francisco–set comedy about the lives of three gay men and their straight female BFF. One of the show’s producers, John Hoffman, explains that he and his fellow writers were so conscious from the start of their LGBT target audience’s love of the Girls that as they initially brainstormed potential titles for the series, he suggested Golden Sons.

The proposed title didn’t fly, but Looking’s 2014 debut season still ended up being book-ended by Golden Girls references. As the show was in mid-shoot of its second episode, its British-born writer/producer/director Andrew Haigh suggested a last-minute script change, replacing lead character Patrick’s reference to Friends’ Ross and Rachel with a recitation of the lyrics to the Golden Girls theme. As Andrew reveals, after each long day of shooting on location, he had gotten in the habit of unwinding in his San Francisco hotel room by watching The Golden Girls. And so was born what would become the series’ running joke, which paid off in the waning moments of the first season’s finale as Patrick climbed into Agustín’s bed with his laptop, recommitting to their roommate tradition of watching the Girls together.

As the episode faded with “Thank You for Being a Friend” over its closing credits, it was an appropriate season ending for a series about a friendly foursome—particularly one that has obvious parallels in terms of its characters: naïve Patrick to Rose, caustic Agustín to Dorothy, and sexually charged Dom to Blanche. As the group’s only female, Doris stands out as its quippy Sophia—although “for the record,” notes Looking’s creator/writer, Michael Lannan, “our Sophia is actually our costume designer, Danny Glicker.”

GOLDEN GIRLS:

THE NEXT GENERATION

“At tapings of Hot in Cleveland, during breaks between scenes, our warm-up comedian, Michael Burger, would often play different TV theme songs for the studio audience. When the Golden Girls theme would come on, everybody would go crazy. And even though I would usually be backstage, that song would pull me out in front of the crowd like a magnet.”

—BETTY WHITE

IN THE SPRING of 2010, TV Land, previously known as a home for reruns of TV classics, decided to get into the business of original programming. And for a cable network looking to make a splash in sitcoms, what better show to emulate than a certain generation-spanning megahit?

The network’s first and so far most successful original comedy, Hot in Cleveland, was the story of three aging Angelenas who decide to move to Ohio after finding they were considered more attractive in the Rust Belt, and their new house’s cantankerous nonagenarian caretaker. That last role, not so accidentally, was played by Betty White. “When I was first thinking about Hot in Cleveland, I actually was thinking about [The Golden Girls and] what those women [would be like] today,” says the show’s creator, Suzanne Martin. “The two shows certainly did have a lot in common.”

Just as had the Girls, Hot in Cleveland’s four leading ladies comprised a supergroup of TV comedy, with each actress already iconic from a previous TV role. And Cleveland’s twenty-first-century foursome hewed to the Golden formula so unabashedly that early on the show’s stars sat down to discuss exactly who compared to whom.

“We’ve been trying to figure it out,” admitted Valerie Bertinelli, who played Cleveland’s trusting and optimistic self-help writer Melanie Moretti. “I do know that I’m probably Rose.” Jane Leeves, too, had a strong viewpoint about her character, the sardonic, unlucky-at-love eyebrow stylist turned private eye Joy Scroggs: “I’m definitely the Dorothy.”

Meanwhile, the former Rose, Betty White, graduated into Cleveland’s Sophia-like part; her character, the cranky but wise Polish-born Elka Ostrovsky, was supplied not only with the wisdom that comes with age but with the show’s most devastating one-liners. But, as Betty’s costar Wendie Malick pointed out, Elka had a strain of Dorothy in her, too. Unlike with the oft-confused Sophia, with Elka, “Nothing gets past her.”

The cast of the Celebration Theatre’s Golden Girls/Hot in Cleveland mashup (left to right): Michael A. Shepperd, Max Greenfield, Hot in Cleveland stars Wendie Malick, Jane Leeves, Betty White, and Valerie Bertinelli, and Millicent Martin.

Photo by SEAN LAMBERT, courtesy of CELEBRATION THEATRE.

Wendie admitted that her character, egocentric actress Victoria Chase, was probably Cleveland’s Blanche. “Although I think you might have to split Dorothy in half, giving some of her sarcasm to Joy and some to Victoria.

“Besides,” Wendie added, “Victoria didn’t sleep around as much as Joy did,” which was, not so coincidentally, the same type of defense Rue McClanahan used to offer for Blanche.

Hot in Cleveland was not shy about paying homage to its Golden ancestor, both on- and offscreen. In March 2014, in the show’s live fifth-season premiere, the star of Cleveland’s spin-off The Soul Man, Cedric the Entertainer, crossed over to Cleveland as his character Reverend Boyce. After Elka delivered a jab about Steve Harvey being the funniest of the Kings of Comedy, Boyce came back with a retort: “Oh, the way Rue McClanahan was the funny one on The Golden Girls?” Betty expertly waited out the laugh as the audience responded to the in-joke. “I never saw that show,” Elka responded dismissively. (Betty would soon get a shot at revenge; immediately after the live episode of Hot in Cleveland, the ninety-two-year-old legend raced over to Soul Man’s soundstage next door to guest star on that show’s live season premiere as well.)

As the fifth season of the bona fide sitcom hit was airing on TV Land, one of its executive producers, Todd Milliner, was brainstorming ways to raise money to support LA’s Celebration Theatre, of which he is a board member and his partner is one of the artistic directors, along with Michael A. Shepperd. When Todd suggested a historic mashup of the Girls from Miami with the ladies of Cleveland, “Ding, we knew we had a winning idea,” Shepperd remembers.

Left to right, Hot in Cleveland co-stars Wendie Malick, Valerie Bertinelli and Jane Leeves walk the red carpet for Betty’s 90th birthday celebration at Los Angeles’ Biltmore Hotel, January, 2012.

After another of Celebration’s troupe members, former Golden Girls writer Stan Zimmerman, suggested a performance of the script for his season-one episode “Blanche and the Younger Man,” the Hot in Cleveland stars divvied up the four iconic roles. Valerie prepared to play Rose, Wendie to play Blanche, and Jane, despite her British accent, would be Sicilian Sophia. The casting happened to fit the women’s Cleveland characters—but the assignments were actually made based on Betty having first dibs. And this time, Betty wanted to play Dorothy.

“This is so surreal,” Stan told the excited audience of the theater company’s benefactors, seated on the CBS Radford lot’s Stage 19 on the night of April 26, 2014. As he introduced the table read of the twenty-nine-year-old shooting script he had unearthed from his files—which included never-before-heard jokes that had been cut for time from the finished episode—Stan gestured at the chair about to be occupied by Betty White. “One of the Girls literally is here,” he noted. “But I watched a rehearsal earlier today. And the Hot in Cleveland cast is invoking such a Golden Girls vibe, I feel like the other three are also here tonight.”

The performance would go on to be a highlight both for the Celebration Theatre, which raised more than enough money to pay off its debt—and particularly, as former Golden Girls script coordinator Robert Spina noted, for Betty White. “Betty was first cast to play Blanche, played Rose for eight years [including Golden Palace], on Hot in Cleveland is essentially playing Sophia, and now has the chance to play Dorothy,” he cited. “So as of tonight, Betty White has gotten to be all four of the Golden Girls.”

In 2010, as Hot in Cleveland began shooting its first season, Betty White scribbled a Golden Girls-themed blessing on the wall of Stage 19 at Los Angeles’ CBS Radford Studios.

Photos by AUTHOR.

SHARING CHEESECAKE WITH

BETTY WHITE

“I love cheesecake, but I never eat on camera. I just toy with it. But ask Rue about what she does. Because I’m telling you, if it’s on camera, it’s a license to steal, as far as Rue is concerned. It has no calories. So she’d not only eat the cheesecake, but when Sophia would make spaghetti, she’d eat that, too.”

—BETTY WHITE

AS AN ACTOR, you get so many bad scripts, but when I read the pilot script for The Golden Girls, I sat up and took notice. It was different from anything I’d gotten. And it was all because of the wonderful writing. The four of us get a lot of credit, but we couldn’t do it if it weren’t for the amazing scripts. I promise you, as an actor you can screw up a good show, but you can’t save a bad one if it’s not on the page.

From the first table read of the script, we knew we were on to something. Everyone was so perfectly cast that the minute you heard the lines coming out of our mouths, it was exciting. I’ve never had a read-through like that. All of a sudden, I’d start throwing them over the net, and I’d get them right back. We all had the same reaction. We could feel the chemistry. We could taste it.

The magic of the show was the way the writers drew our characters so distinctly. All these years I’ve used the analogy of four points on a compass. We balanced each other out beautifully. And not only were the lines wonderful, but they would shoot the reactions of the other characters. So pretty soon, since the audience got to know these women so well, they’d start to anticipate. “Oh, how is Bea going to react to that?” Or Rue, or Estelle. It made for a very exciting seven years.

Right from the beginning, Rue would always remark how evidently Rose and Charlie had had a very active sex life. Off camera, that was always Rue’s thing: “Come on, Rose gets more action than Blanche does!” That was the beautiful part about the writing. We could get away with murder and talk about so many things. At our age, everybody knew we’d been around the block, and so the talk wasn’t as salacious as it would have been with younger women. And it was funnier because we were our ages, rather than if we had been young enough to be participants.

I always believed that Rose was truly naïve more than dumb. I’d hear people calling her ditzy or a dumbbell, and I would defend her. Of course, she did think her second-grade teacher was Adolf Hitler, so it was a very fine line. In playing Rose, I found that the most interesting challenge was that even though as an actor I had to kind of think funny and play on things in my head I had to be careful to keep the awareness not only out of my mouth but also out of my eyes. Rose couldn’t ever look like she got it. She had to be innocence personified. That was the saving grace that would allow her to get away with saying something like “Can you believe that backstabbing slut?” about Blanche. Those were the lines where the producers would warn me: “You never get it. You’re never too smart for the room.” They knew coming from Rose the line would work, but coming from me it wouldn’t.

Rose is like me in some ways, in her optimism and her wanting to think that life always has a happy ending. That was in the script, so I don’t think I brought that to the role, but it was just something that was terribly comfortable for me. She also has a Viking temper—like me, I’m afraid—and wasn’t always sweetness and light. When she got mad, she got really mad. But I’m not as prone to telling someone off. No point in getting into a confrontation—I’ll just wait until they go home and then I’ll bitch like mad.

From the start, seventy-five percent of our mail has always come from young people, especially in their teens and early twenties. Fans will often come up to me and quote every line of a St. Olaf story, and I don’t blame them. They were brilliant. When I’d read a script and see one, I’d be thrilled. I don’t do accents, but there was just an undulating rhythm to those words that I was able to pick up on. Still, sometimes before work if I’d see a newspaper story with some very difficult-to-pronounce Scandinavian name, I’d think, “Uh-oh—I’m going to get it.” And sure enough, it would show up in the script. I swear the other girls would make bets that I’d never make it through some of these difficult words. So when I told a St. Olaf story, I always had to look over their shoulders instead of locking eyes with any of them. Because I knew they were just sitting there, thinking, “You’re going to screw up. You know you are!”

When the show premiered we were at number one, over Bill Cosby, who at that time owned the world. We felt, well, that’s just curiosity, that first show. Four old broads are not going to continue to get that kind of ratings. Well, we stayed, and I don’t think we were ever out of the top ten, which is such a privilege. It was just one of those things that comes along I would say once in a lifetime—but my “once in a lifetime” had already been used up with Mary Tyler Moore. So to get it again—and then on Boston Legal, with David E. Kelley’s writing—I mean, how lucky can one old broad get?

AUTHOR’S UPDATE:

In an appearance on Larry King Now in April 2014, Betty had to amend her last statement from 2006 to reflect her most recent work. When Larry asked how she would like to be remembered, Betty thought for a moment. “I think for Life with Elizabeth, maybe, or The Golden Girls. And Mary Tyler Moore!” Betty responded. “How lucky can you get? To get one big series or maybe two—but to get three, and now, with Hot in Cleveland! We’re having a ball.”

After The Golden Girls ended, the then-seventysomething Betty kept busy not only with a season of the doomed CBS sequel series The Golden Palace (1992–93), but by appearing in a variety of TV guest spots, plus in regular roles in the short-lived sitcoms Bob, opposite Bob Newhart, on CBS (1993); ABC’s Maybe This Time with Marie Osmond (1995–96); and CBS’s Ladies Man (1999–2001), playing the mother of Alfred Molina’s title character. After several guest appearances on ABC’s legal drama The Practice, Betty brought her secretary character, Catherine Piper, to the cast of its spinoff series, Boston Legal, where she appeared from 2005 to 2008. During much of that same period, from 2006 to 2009, she also popped up on CBS’s daytime soap The Bold and the Beautiful as Ann Douglas, the long-lost mother of that show’s matriarch Stephanie Forrester; the ever-energetic Betty ultimately outlived Ann, who died on the soap in November 2009.

Betty White addresses the press at the taping of an NBC special celebrating her 90th birthday in January, 2012.

Photo by AUTHOR.

Betty’s big-screen career blossomed as well, with hilarious roles as a foulmouthed, alligator-loving old lady in 1999’s Lake Placid, and in 2003, as racist busybody neighbor Mrs. Kline in Bringing Down the House.

But 2010 turned out to be Betty’s banner year; just as she turned eighty-eight, her career suddenly burned hotter than ever. In January of that year, she accepted the Screen Actors Guild Life Achievement Award—an honor that usually comes at the end of a career, but for Betty turned out to be just the opening curtain of yet another act. That spring continued with what turned out to be a well-timed blitz, parlaying the heat from Betty’s role in the 2009 Sandra Bullock–Ryan Reynolds film The Proposal into a buzzed-about appearance in a Snickers commercial during the Super Bowl.

A Facebook petition that built throughout the spring of 2010 landed Betty the gig hosting a May episode of Saturday Night Live—for which she ultimately won her sixth Emmy Award. Just over a month later, on June 16, Betty debuted in yet another hit series, TV Land’s Hot in Cleveland.

In 2011, Betty published her seventh book, a volume of her wit and wisdom on such topics as love, friendship, animals, aging, and television called If You Ask Me (And of Course You Won’t); in February 2012, she became, at ninety, the oldest person ever to win a Grammy Award, beating out such competition as Tina Fey and Val Kilmer in the Best Spoken Word Album category for her reading of the book.

Also in 2012, she launched Betty White’s Off Their Rockers; the hidden-camera comedy show, which she also hosts and executive produces, ran for two seasons on NBC before jumping over to Lifetime for its third. To mark Betty’s big nonagenarian celebration in January, NBC gathered the biggest names in comedy for a tribute special. Before the cameras rolled, but after properly greeting her guests—such as Mary Tyler Moore, Valerie Harper, Ed Asner, Carol Burnett, Vicki Lawrence, Carl Reiner, Tina Fey, Amy Poehler, and her Hot in Cleveland costars, Valerie Bertinelli, Wendie Malick, and Jane Leeves—Betty, in a sparkly sky-blue gown, presided over a press conference in one of the ballrooms of downtown Los Angeles’s Biltmore Hotel. I asked her if Betty White was turning ninety, does that mean Rose Nylund and her Mary Tyler Moore Show character, Sue Ann Nivens, were as well?

“Rose may very well be ninety, but if Sue Ann is, she’ll never admit it,” Betty replied with a laugh. “She would lie, and would knock off a couple of decades.

“My mother always told me, ‘Never lie about your age. Brag about it,’” Betty added. “And when you get to this point,” she said—acknowledging with a sweep of her arm the sheer size of the celebration in her honor—“you get spoiled so rotten that I love being ninety.

“And I’ll see you again in ten years!”

SHARING CHEESECAKE WITH

RUE McCLANAHAN

(1934–2010)

“Betty says that I always ate the cheesecake, but it’s not true. I would actually put a bite of cheesecake on my fork and move it close to my mouth. Then when the camera cut to someone else, I’d put it on a plate under my chair. By the time they’d cut back to me, I would pretend to be chewing.”

—RUE McCLANAHAN

IT WAS STATED from the very beginning that Blanche was more Southern than Blanche DuBois. But the accent in Atlanta where Blanche is from is very slight—hardly funny enough. So I decided to go with my instinct and make her a kind of phony. My mother had a cousin, Ina Pearl, who was from southern Oklahoma like everybody else, but put on an accent that was part extreme Southern belle and part her idea of upper-class British. It was a remarkable accent and it was really obviously hers alone. Nobody in the family knew where she got it from and although she didn’t think she was being funny, I always did. So I played Blanche the way I felt Blanche. She thought an accentuated Southern accent like Ina Pearl’s would be sexy and strong and attractive to men. She wanted to be a Southern heroine, like Vivien Leigh. In fact, that’s who I think she thought she was.

But as we rehearsed the pilot, Jay Sandrich said to me, “No, no—I don’t want to hear a Southern accent.” He said he wanted just to hear my regular Oklahoma accent, which he thought was Southern. Well, there’s no arguing with the director. So I sort of did what he asked and used a modified sort-of-Southern accent. When I heard we got picked up for thirteen episodes, I worried about it for a couple of months. Finally, when we came back to shoot in July, I went to Paul Witt and Tony Thomas and said, “Okay, I know I’m not supposed to play it with a Southern accent, so I have an idea: I’ll do a real Mae West.” And they said, “What are you talking about? Of course Blanche has a Southern accent!” And I said whew! And was thrilled I got to play it the way I wanted to in the first place.

I needed to pick a voice that wasn’t Rue that would work to help me create a character. You can’t just do your regular voice, your regular walk, your regular beliefs, your regular anything if you’re creating a character. For example, the Blanche walk came to me very quickly after the pilot. That’s not my natural walk, but it is hers. And I don’t think there’s anyone else on earth who walks like Blanche. Movement is very important to me in developing a role, and I think Blanche’s walk showed self-assurance and her always being on top of the situation. If she was at the Rusty Anchor or on a date, she felt it was irresistible and beguiling. The shoes were a big part of it, the sound they made. I always have to know what a character is going to wear, and once I discovered the walk, Blanche always wore those slingbacks.

As self-involved as she was, Blanche also had a sense of humor about herself, if the jokes were coming from the right place. It was a delightful thing for me to discover early on that Blanche would find Sophia adorable. It’s really her fault that Blanche got to be known as a slut, but Blanche would forgive her because she’d had a stroke, and find everything she said funny and endearing. So if Sophia said something particularly nasty, I’d laugh like “aw, you cute little thing,” and never took offense. It helped the jokes work, because it avoided a sour note of actual hurt feelings, and kept the audience with us.

Blanche also had a conservative side that was a lot unlike me; she could be homophobic, which I’m not, and for example she was grossed out by her daughter’s artificial insemination, which I wouldn’t have been at all. I had to act all that. Really, none of us is at all like our character—Betty probably the least of all, because she has nothing but brains. Estelle isn’t at all pushy and vitriolic like Sophia—but they both were New York funny. And because Dorothy is probably the “straightest,” least eccentric character, Bea is like her in that way. They both have a very funny take on people and are quick-witted, not suffering fools gladly. But certainly Dorothy’s failure in life is completely different from Bea’s huge successes. And when people ask me if I’m like Blanche, my standard answer is: Just look at the facts. Blanche is a man-crazy, glamorous, extremely sexy Southern belle from Atlanta. And I’m not from Atlanta.

But in truth, I actually don’t see Blanche as a slut at all. She actually had fewer dates than anybody if you go back and count. Sophia had more going on sexually than Blanche did. But Blanche talked a lot. I think that she was married to George for a long time, and she never got over him. She was always looking for a replacement; she was looking for love. She was also oversexed. I had a best girlfriend like that. They do go well together. I’m not oversexed, but I was looking for love, and I got myself into a lot of trouble that way. In fact, my memoir is titled My First Five Husbands . . . And the Ones Who Got Away. Maybe there is more similarity with Blanche than I’ve realized.

AUTHOR’S UPDATE:

Following the end of The Golden Girls and Golden Palace, Rue continued to pop up all over the small screen, in TV movies such as the 1994 made-for-TV sequel to Nunsense, and in guest roles on Boy Meets World, Murphy Brown, Touched by an Angel, and King of the Hill. In the fall of 1999, she played a regular role in the WB’s Safe Harbor, as the mother of the widowed sheriff, and grandmother to his three sons; the series lasted only eleven episodes.

Rue continued to appear on the big screen as well, in key roles in independent films and in small roles in the big-budget films The Fighting Temptations (2003) and Starship Troopers (1997). Also in 1997, she appeared in the feature film Out to Sea as Mrs. Ellen Carruthers, the owner of a cruise ship that apparently caters to a similarly Golden geriatric set, employing Jack Lemmon and Walter Matthau as dance instructors. And that same year, Rue successfully underwent treatment for breast cancer.

With her return to New York, Rue also returned to the stage, off Broadway in The Vagina Monologues and in the Broadway productions of Wicked and The Women (2001). As that production’s Countess de Lage, she was wont to proclaim her need for “L’amour, l’amour!” Rue then catalogued her own similar real-life quest in her 2007 memoir.

Rue’s final acting role was in the Logo network series Sordid Lives in 2008. Although Texas matriarch Peggy Ingram had been played by actress Gloria LeRoy in the original film—in which the character died—in the series version, as embodied by Rue, she was not only alive but embarking on a secret love affair with a younger man.

The role offered the seventysomething Rue the chance both to play a still-vital woman and to support a series by her friend, out gay creator Del Shores. Rue supported presidential candidate Barack Obama in the 2008 election, and advocated for the legality of same-sex marriage. In January 2009, she appeared in the star-studded event “Defying Inequality: The Broadway Concert—a Celebrity Benefit for Equal Rights.” That following November, she was scheduled to be honored for her lifetime achievements at the event “Golden: A Gala Tribute to Rue McClanahan” at San Francisco’s Castro Theatre, but was forced to cancel due to cardiac problems. Following triple-bypass surgery, Rue suffered a minor stroke early the next year. After suffering a brain hemorrhage, Rue (née Eddi-Rue) McClanahan died at New York–Presbyterian Hospital on June 3, 2010, at age seventy-six.

In 2006, I sat down with Rue to conduct an interview for the Archive of American Television, a daylong discussion of the actress’s life and career. At the end of the grueling shoot, I asked her how she would like to be remembered. “As alive,” she quipped, before thinking more seriously about it, and turning the question back on me. “But you’ve got to ask me about my proudest achievement in life!” she insisted. And so I did.

“My son, Mark [Bish], the jazz guitarist,” Rue replied, sounding very unlike Blanche, who always struck me as more self-involved than maternal. “He’s also an artist. He builds, he paints, he draws. And he’s my biggest pride. If I had done nothing else, I’d be satisfied that my life had meant something.”

LESLIE JORDAN

the Actor and Author

REMEMBERS RUE McCLANAHAN

WHAT A BAD queer I am. I don’t know much about The Golden Girls, because I did not get sober until 1997. I was too busy running the streets of West Hollywood to watch the show. I do come across it quite a bit in reruns. The first thing I notice is the sunny, pastel set that is so indicative of retirement complexes in Florida. My sisters worked for the Villages in Lady Lake, Florida, which is one of the largest retirement communities. They have so many stories; it is no wonder the show was able to capitalize on that arena.

And of course, if I had to pick a favorite Golden Girl, it would have to be Blanche. My contribution to this missive will have to be my association with the real Blanche, Miss Rue McClanahan. We worked together on the TV series Sordid Lives, based on the hit movie of the same name by Del Shores. It ran on Logo for one season. We were all dropped off in Shreveport, Louisiana, and had to “make do.” The show was a prequel to the movie and Rue’s character was already dead when the movie began, but her character was certainly alive and well in the TV series.

I could not wait to meet Rue, and just knew we would hit it off. I was right! We met in a casino in the hotel where we were staying. Rue McClanahan was so much like her character Blanche it’s hard to tell where Rue ended and Blanche began. I loved the quote that Del uses about why Miss McClanahan was so eager to be a part of a project where there was not a lot of money involved. She read the script and called Del that night, personally, to say, “I’ll do it. I never thought at my age I’d get an opportunity to play a woman in love again.”

A few years after the TV series was canceled, we all went on the road with a show we called An Evening of Sordid Comedy. It was Rue, Caroline Rhea, Del Shores, and me. Rue was having some back problems, and had to take pills for the pain. They made her a little testy, to say the least. Del would sell tickets to a meet and greet after each of our performances. Rue loved her public, but she just wasn’t feeling up to meeting all those people. She asked me before we went on in Dallas, “How long are you gonna go?” I said, “The same as you, Rue. We each get twenty minutes.” She looked me straight in the eye. “Do not go over. We’ve got to do this damn meet and greet. I don’t feel well.”

Well, you certainly would not have known she didn’t feel well. She walked onstage, sat down (she did sit-down comedy at her age, not stand-up comedy) and brought the house down with her stories. Trust me, she went way over her allotted twenty minutes. Then, I walked onstage and was killing! Twelve hundred gay Texans! What a response I was getting! But then all of a sudden the crowd really went apeshit. I turned around, and here was Rue marching back onstage. She walked right up to me and ran her fingers over her throat, which I took to mean, “Wrap it up!” The crowd could not get enough of her! I was livid!! But how long can you stay mad at Rue McClanahan? I miss her desperately.

SHARING CHEESECAKE WITH

BEA ARTHUR

(1922–2009)

“I hate cheesecake. I didn’t like the cheesecake scenes, either – I didn’t find them amusing, and thought of them as just a segue. But audiences love it, and to this day they still talk about it. And when I do my one-woman show and talk about this, people will come backstage and say, ‘Do you really love cheesecake? Don’t lie!’”

—BEA ARTHUR

THE FIRST THING I noticed about The Golden Girls pilot was that it was a beautiful script. It had an extra character, a gay house man, who was very charming, but they cut him by the very next episode. I don’t think they had any idea that just the four of us would be so strong together. And we were lucky enough to have brilliant writers on the show and a fabulous director, Terry Hughes. It was a great combination of all the elements.

I think the relationship between Dorothy and her mother makes for one of the most brilliant comedic duos I’ve ever known. First of all it was so ludicrous, with the fact that physically Estelle and I are so completely different. And then their love/hate relationship, where they could be so sweet yet so cutting with each other, was so real, and was just marvelous the way it was written. I also loved Dorothy’s relationship with Stan. She could be so mad at him, and claim she hated him, but the lines were written to say that they obviously still loved each other. And so it became a comedic relationship that really paid off.

I remember one scene [in season 3 episode “My Brother, My Father”] where Stan is staying over, and I’ve made him sleep on the floor. The camera is on me, and suddenly I hear him laughing. And I have a line like, “Stanley, if you’re doing what I think you’re doing . . .” I remember saying to the writer, “How are we permitted to do this?” We certainly got away from the censors more than we had on Maude, where every third day of every week we had to read the entire script to the network and then Norman Lear would start his negotiations with them. “I’ll cut that line or that section, but Bea has to say that line.” It was one fight after another. And that struck me when we were doing “Journey to the Center of Attention” in the seventh season, and Rue does a thing whereshe sits in a guy’s lap and does the “is that a gun or are you just happy to see me” joke. But it seems like that leeway came with time, because in the pilot episode, we had to change the line where Sophia calls Blanche’s fiancé a “douchebag.”

Sometimes rather than a written line, the writers would want a reaction shot from one of us. They and Terry Hughes were so good at knowing what was and was not going to work. People always ask me about my “slow burn.” I just know that I tried to keep my reactions honest. I didn’t even start out doing comedy, but I think you have to be real. So many really brilliant actors, once they are told that they’re in a comedy, turn into people from another planet. There is no similarity between their characters and reality. So you just have to make sure as an actor to make everything real for yourself.

That had been easier for me on Maude, because we taped on Tuesdays, which meant we had a few days over the weekend of not rehearsing where suddenly it would pop into my head “I know how to do that!” But there were at least a few things about Dorothy that were easy for me to find real, because they are like me. I always tell people we’re both 5´9½˝ in our stocking feet, and both of us have very deep voices. But we’re also the same in that like Dorothy, I hate bullshit. I call it bubble-pricking. Being the great leveler, the voice of reason who brings other people back down to earth. Dorothy was the voice of reason on that show. Left to their own devices, I don’t know how the other women could have survived.

I also get asked all the time if we’re going to do a reunion. But the way I see it, why would we? We’re not going to be any better than we were, or top some of the great shows we did. I left Maude after six years and Golden Girls after seven, because even then, I realized we couldn’t top what we’d already done. Golden Girls started to strain a bit by the end, and wasn’t as hysterical as it had been, so I thought it was time to leave. Today, I still have people constantly recognizing me, saying “Oh my God, it’s Dorothy!” It is so sweet and so nice. Often, flight attendants will come up and say something to me when I’m traveling. After all these years, I am delighted. It is incredible when you realize, The Golden Girls is all over the globe.

AUTHOR’S UPDATE:

After leaving The Golden Girls, Bea returned once to small-screen Miami, as Dorothy Zbornak spent a two-part episode in the fall of 1992 visiting her Girls at their hotel, the Golden Palace. Throughout the ’90s, she was in demand as a lively talk show guest, and popped up in such unscripted fare as a tribute to her former Mame co-star and close friend, Angela Lansbury, and as a presenter at the Tony Awards. In 2002, she appeared on both The Daily Show with Jon Stewart and on an Oscar-themed comedy special, The Big O! West Hollywood Story, hosted by that show’s gay movie critic [and the author’s husband] Frank DeCaro.

Bea continued to appear on TV comedies as well, with guest spots on Dave’s World in 1997 and Futurama in 2001, and in recurring cameo appearances on Showtime’s Beggars and Choosers in 1999. In 2000, Bea was nominated for an Emmy for her guest role as babysitter Mrs. White in the first season of Malcolm in the Middle, and she popped up again in another prominent role, as Larry David’s mother, in a 2005 episode of Curb Your Enthusiasm.

But after finding TV fame as Maude Findlay and Dorothy Zbornak, Bea ended up being most compelling when she appeared on the small screen just as herself. At The New York Friars Club Roast of Jerry Stiller, televised in 1999 by Comedy Central, comedian Jeffrey Ross made a hilariously crude reference to “Bea Arthur’s dick,” and Bea’s reaction from the dais was priceless.

Then, in 2005, it was Bea’s turn to do some roasting, as she read aloud from the semi-autobiographical novel Star Struck by honoree Pamela Anderson, her friend and fellow supporter of animal rights. “The story concerns a blonde, very large breasted actress, imaginatively named Star, who plays a lifeguard on a hit television show,” Bea deadpanned. “And she becomes actively involved romantically with a tattooed rocker. And a videotape that they have made of their sexual escapades is leaked to the public. Pam, where do you come up with this shit?!” 83-year-old Bea proceeded to read particularly tawdry passages from the book, with her elegant, Broadway-honed elocution. And she killed.

Having gotten her start in theater, Bea continued to perform on stage throughout her life, appearing in Los Angeles-area productions of Renee Taylor and Joe Bologna’s Bermuda Avenue Triangle in 1995-96, and in Anne Meara’s After-Play in 1997-98. Having developed a traveling act in the ’80s and ’90s, she continued to tour through 2006, including a 2002 New York run titled Bea Arthur on Broadway: Just Between Friends. A collection of stories and songs based on her life and career, the show was extended beyond its initial limited run, and was nominated for a Tony Award for Best Special Theatrical Event.

In the spring of 2008, Bea rejoined Rue McClanahan and Betty White in Santa Monica, California for the taping of the 6th Annual TV Land Awards, where The Golden Girls was honored with the network’s Pop Culture Award, presented to the three ladies by Steve Carell.

It was to be Bea’s last televised appearance. Beatrice Arthur, née Bernice Frankel, died of cancer on April 25, 2009 at the age of 86.

At her memorial service that September at New York’s Majestic Theater, her longtime friend Dan Mathews, vice president of People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals, spoke about his beloved Bea as both a force of nature and a fascinating study in contradictions. Although tall and physically imposing, he noted, Bea would often be reduced to tears by stories of animal suffering. And yet, on one afternoon at her home in California’s Pacific Palisades, when Dan the ardent vegan was helping prep for a fundraising dinner, the equally ardent non-vegetarian Bea asked him to cut up some onions and press them into the meatloaf she was preparing. “And I thought, ‘I’m a hardcore vegan, here at Bea Arthur’s house for a PETA meeting, and I’m helping her make a meatloaf?!’” Dan remembers. “But then, I don’t know if it was the look in her eye, or the knife in her hand—but I did what she said!”

BILLY GOLDENBERG

Bea’s Friend and Longtime Accompanist

REMEMBERS BEA ARTHUR

a Star Who Gave Back to the LGBT Community

I MET BEA in 1981, when we were asked to work together to prepare material for a benefit for the ACLU. We rehearsed for a day, and the next morning she called me up and said, “Would you come to dinner?” I said, “Of course”—and that was the beginning of a very long friendship.

It turned out we hated all the same, often very famous people. There is no bond like hating the same people! After a while we started to work on some songs together. After all, people who came to parties at Bea’s house were always asking her to sing. And she knew a lot of songs and performed them well, from Kurt Weill to Bob Dylan. One day, our mutual friend Nick Perito, who was the musical director for Perry Como, urged us to do a show.

As Nick reminded us, Bea knew every funny writer in the business, so we started interviewing writers and asking them to submit ideas. But they all wanted Bea to do what they were used to from her: very campy and gay material. We wanted the show to be more personal to Bea—not necessarily autobiographical, but about things Bea thought about life. So I sat Bea down with a tape recorder, and asked her to tell every funny story she’d ever told me, with her particular inflection, and with her typically funny asides and comments. We had it transcribed, we edited it, and we had a show, which we tried out in Palm Springs during Bea’s weekend break from The Golden Girls.

We did the show—that we had planned for 30 minutes but which turned into an hour, because of Bea’s ad-libs and the audience’s laughter—at the town’s most prestigious golf course, and all of the richest gay men were there. We eventually traveled the world with the show. We had our best reaction in South Africa, where I’m told The Golden Girls was on seven times a day. African-American audiences in particular loved Bea, too. But of course, gay men were her biggest fans. We always knew when the audience was predominantly gay, we couldn’t miss.

In 2005, we did a one-night-only show in New York to benefit the Ali Forney Center, which Bea had become very devoted to, doing interviews on their behalf and whatever else they needed to serve the city’s homeless LGBT youth. And throughout the years, we very often played for an AIDS audience. After the show, Bea would come out the stage door, and all these guys in wheelchairs would be waiting. Bea would talk to them, and go and kiss a couple of them. She spent hours, and they appreciated it incredibly. But Bea had a special way like that, always liking to help people.

Soon after Bea and I started doing the show together, we were invited to take it to Westport, Connecticut, to the White Barn Theater. In the first rehearsal, the director, our friend Donald Saddler, reminded me that if I was going to be on stage with Bea Arthur, people would be looking at the both of us, so I couldn’t just look at my music or at the piano. He told me the first rule of performing was reacting. And so Bea and I began to try things out each night on stage. Some nights, as we walked off, she’d say, “You did something tonight—I want to know what it was.” I’d tell her, and she would often say, “Okay, I think we could do something further with that,” and we would invent fun little bits of interplay.

I’ll always remember one of those bits: another director later suggested that before Bea would sing “The Man in the Moon Is a Lady,” one of her famous songs, in the encore, she should walk over to me and whisper something in my ear. It didn’t matter what she would say—it could be “fuck you”—and often was. She would then walk downstage, and I would have a line: “You’re not serious.” He expected we’d get a big laugh out of it. So the first night, Bea whispered in my ear, and I said my line right away—and no laugh. The second night, I tried making a disdainful face—and still nothing. So on the third night, I decided to try something. That night, I let Bea walk off almost to the edge of the stage, and then I said to her, “You’re not serious.” It got a huge laugh.

As we walked off stage that night, Bea said to me, “Darling, you’ve just discovered the secret of comedy.”

I said, “What’s that?”

And she said, “Waiting.”

To this day, I can tell a joke better than anybody because of all the training I got with Bea. I learned from the best.

Golden “Girls”: Drag Tributes to TV’s Fab Foursome

![]()

NEW YORK, NY

IN 2003, NEWLY dating couple John Schaefer and Peter Mac first came up with the idea of celebrating the Girls’ appeal to gay viewers via an all-male stage production of two of the show’s episodes, “Break In” and, inspired by the fun they had pronouncing the word “LES-bian” à la Rue McClanahan, “Isn’t It Romantic?” As a payback to Estelle Getty for her early fund-raising to fight AIDS, their show Golden Girls . . . Live, which ran for sixty performances at the cabaret room Rose’s Turn in Greenwich Village, raised money to fight progressive supranuclear palsy, the disease with which Estelle had been at the time diagnosed. (The diagnosis was later changed to Lewy body dementia.)

After coverage in Entertainment Weekly, the tiny cabaret club routinely found itself with a wait list seventy-five deep. “It was a lot like Rocky Horror,” Peter remembers, because the audience comprised of gay men, bachelorette parties and sorority groups “would say the lines with us. People had fun being so close to the ‘Girls’ who weren’t trapped in that little box anymore.”

Then, in the spring of 2014, writers Nick Brennan and Luke Jones reprised the idea by joining with Chad Ryan and John de Los Santos for Thank You for Being a Friend, an unauthorized parody musical at the Laurie Beechman Theatre featuring four characters named Dorothea, Blanchet, Roz, and Sophia as well as original odes to Miami and, of course, cheesecake.

SAN FRANCISCO, CA

IN 2006, SAN Francisco drag icon Heklina began staging a tribute to the Girls in a friend’s home in the city’s Lower Haight neighborhood. Quickly outgrowing that original parlor, the show then moved to the five-hundred-seat Victoria Theatre, where it has become an annual holiday tradition. The Golden Girls: The Christmas Episodes stars Heklina as Dorothy, female impersonator Matthew Martin as Blanche, Pollo Del Mar as Rose, and Cookie Dough as Sophia, complete with rattan purse and shuffling gait. “It’s a perfect fit,” Heklina explains, “because with the clothes they wear, the situations they get into, Bea Arthur’s genius comic delivery and Blanche’s reputation for being a slut, the Golden Girls are all like drag queens anyway.”

Clockwise from top: Heklina, Matthew Martin, Cookie Dough, and Pollo Del Mar as the Girls.

Photo by KENT TAYLOR.

LOS ANGELES, CA

IN THE SUMMER of 2014, another California drag doyenne, Jackie Beat, teamed up with an import from New York, Sherry Vine, and actors Sam Pancake and Drew Droege for their own Golden Girlz Live at LA’s underground Cavern Club Theater at the Casita del Campo restaurant. Tall Jackie, whose own home contains a room she has turned into a shrine to the four holy ladies of Miami, made for the perfect Dorothy, while Sherry essayed a vampy Blanche, Drew a ditzy Rose, and Sam a bespectacled comic Sophia in performances consisting of two episodes from the troupe’s growing repertoire of episodes, including “The Flu,” “Blanche and the Younger Man,” “Isn’t It Romantic?” and “A little Romance.” The foursome reconvened in the spring and summer of 2015, with more weekends scheduled to come. But Jackie says she’s already noted some VIPs in the basement theater’s tiny audience. When Golden Girls writer Winifred Hervey caught the show in 2014, Jackie says, “she came backstage after the show and said, ‘Thank you for keeping our words alive.’”

PORTLAND, OR

IN 2013, INSPIRED by Heklina’s holiday success, Trenton Shine decided to round up some “Girls” of his own to reenact the Girls’ two holiday episodes at Portland’s Funhouse Lounge. After their sell-out success, the Portland Girls returned the following summer, presenting “Isn’t It Romantic?” and “Sisters of the Bride” with a revised cast including Trenton himself as Dorothy—“which people expected me to do, because I’m tall and sarcastic,” he explains—and the roles of Rose, Sophia, and Blanche played by Scott Engdahl, Randy Tutone, and locally known drag queen Honey Bea Hart. By yuletide 2014, the troupe’s repertoire included “My Brother, My Father” as well, with impressive impersonations of Stan and Uncle Angelo by Andy Barrett and Sean Lamb. And at Christmas 2015, the show evolved again, this time with an all-new script in which the Girls performed in a nativity pageant at Dorothy’s school.

All told, the productions have raised over twenty-eight hundred dollars for the antidiscrimination advocacy group Basic Rights Oregon, and five thousand dollars each for the human services charity JOIN and the Cascade AIDS Project. The performances—each of which began with a selected audience member singing “Thank You For Being a Friend” as the cast acted out the opening credits—had a profound effect on their audiences as well, Trenton explains. “We’ve found that people are really emotionally attached to The Golden Girls, and will come up to us, crying, to say, ‘Thank you so much for doing this.’”

The LA troupe’s recreation of season 1 episode “Blanche and the Younger Man,” starring Mario Diaz as Dirk, Drew Droege as Rose, Sam Pancake as Sophia, Sherry Vine as Blanche, Melanie Hutsell as Alma Lindstrom, and Jackie Beat as Dorothy.

Photo by JACKIE BEAT.

NEW ORLEANS, LA / PROVINCETOWN, MA

HAVING ONCE PLAYED Blanche when Heklina brought her Girls to New Orleans, drag diva Varla Jean Merman joined her longtime friend and collaborator Ricky Graham in 2012 to mount their own hometown stage rendition. Their Big Easy production of The Golden Gals became such a smash, selling out its two month-long weekend runs, that Varla then decided to export the Gals to the gay summer mecca of Provincetown, on the tip of Massachusetts’ Cape Cod. The summer 2014 edition, stitching together the full episodes of “In a Bed of Rose’s” and “Isn’t It Romantic” with one of the vignettes from “Valentine’s Day,” proceeded to sell out every single one of its nightly performances at the Art House theater from early June through Labor Day weekend; the Gals then returned in the summer of 2015 and beyond. Each time, the show’s cast has included Varla, with her perfect impersonation of Blanche—“I’ve noticed that Rue as Blanche always led with her breasts, so I play it with my breasts shaking and head bobbing,” she says—plus Ptown theater impresario Ryan Landry as Dorothy, Olive Another as Sophia, and Brooklyn Shaffer playing Rose. That last role, Varla explains, is always the hardest to cast, “because Rose has to be sweet and innocent, and it’s hard to find a man who can play that.”

BOSTON/SALEM, MA

A FEW YEARS after their first turn playing the Girls in New York, John Schaefer and Peter Mac moved west and attended Heklina’s show on a weekend in San Francisco. Soon after the couple, now known as John and Peter Mac since their 2014 wedding, “decided to give Golden Girls fans the reunion they never really got,” John remembers. And so, running for 194 performances at the Los Angeles gay bar Oil Can Harry’s in 2012–13, their “Lost Reunion Episode” took place at the funeral of Blanche’s uncle and Dorothy’s husband, Lucas Hollingsworth, bringing all four Girls back together—and sidestepping the debacle of Golden Palace.

In the fall of 2014, while performing another show at the Opus Theater in Salem, Massachusetts, John and Peter were inspired by the witchy environs to write and perform a “lost” Golden Girls Halloween “episode,” in which English teacher Dorothy visited town to research her teaching of Arthur Miller’s play The Crucible, with the other three Girls in tow. The couple followed with a second show, “The Golden Girls Lost Christmas Episode,” before premiering yet another original hour, “The Lost ‘Shady Pines, Ma’ Episode” at Boston’s Jacques Cabaret the following spring. Each show, Peter explains, contained “eighty percent new material, and twenty percent classic lines fans remember.”

The Golden Gals at Provincetown’s Art House theater in 2014 (clockwise from top): Varla Jean Merman, Brooklyn Shaffer, Olive Another, Ryan Landry.

Photo by MICHAEL VON REDLICH.

Back in 2003, Golden Girls . . . Live was visited by two of the show’s early writers, Stan Zimmerman and James Berg; later, producer Marsha Posner Williams caught John and Peter’s L.A. show. But there were still a certain four older ladies the guys always wished would pop by. As the 2003 Entertainment Weekly article covering the show had noted, Rue McClanahan herself once tried to attend at Rose’s Turn, but couldn’t secure a seat.

John and Peter still hope to this day they’ll look out one night and see Betty White in the crowd. After all, they do know for sure that Betty is aware of their act. Back in September 2003, Betty appeared on one of the earliest episodes of Ellen DeGeneres’s daytime talk show, in which the host asked her if she knew about this new show in New York where four gay men played the beloved Golden Girls.

“Yes,” Betty replied with enthusiasm. “And I hear they play them better than we did!”

SHARING CHEESECAKE WITH

HARVEY FIERSTEIN

the Legendary Actor and Playwright on

ESTELLE GETTY

(1923 - 2008)

YOU CAN’T BELIEVE everything Estelle said in that autobiography she wrote, If I Knew Then What I Know Now . . . So What? The book presented what Estelle wanted to show the world, her public persona. But I would love to have read Estelle’s real story. As I used to say to her, if the world had known where Estelle really came from, and what magic had happened to her, they would have loved her ten times more.

Whatever stand-up Estelle had done early in her life, whatever community theater, when I met her, she was a housewife in Bayside, Queens. Named Estelle Gettleman. Later on, I would hear her telling people she was from Long Island, and I’d tease her and yell, “You’re from Queens!” And she’d yell, “Long Island!” Her husband, Arthur, had a business changing automobile glass, and they were a very funny, curmudgeonly couple. Estelle was friends with Ann and Jules Weiss, who were supporters of the La MaMa theater, where I was at the time. And so Estelle used to come to see all my shows. When I wrote Flatbush Tosca, I cast Helen Hanft in it, but then for whatever reason, she decided not to do it. The Weisses recommended Estelle, and she came in and auditioned—but then an actress named Suzanne Smith, with whom I had done Andy Warhol’s Pork, said she would play the role. Estelle was mad at me, but when I wrote my next play, International Stud, which was the beginning of Torch Song Trilogy, Estelle came to see it, and loved it. Same thing with the next part, Fugue in a Nursery. Estelle kept saying to me, “Why don’t you write a mother, and I’ll play her?”

So for the third part of the trilogy, Widows and Children First!, I did write a mother, and gave the part to Estelle. We did a reading, and she was hysterical. Estelle was ready to go legit, and to be an actress. In fact, you can tell you have a first edition of the book of Torch Song Trilogy by the cast list for the third act. Because just as the play was being published, Estelle called me up and said, “I want to be listed as Estelle Getty.” They had to reset the print, and in doing so, her name ended up not lining up with all the other actors’.

Harvey Fierstein and Estelle Getty in Torch Song Trilogy, 1982.

Estelle had strong opinions, and was the expert on everything. When we were rehearsing the big fight scene in Torch Song Trilogy, Estelle objected to the speech her character gives to mine about what it’s like to be widowed. She told us, “I don’t want to say that, because that’s not the way it is. My sister lost her husband, and that’s not the way she felt.” And I said, “Estelle, just shut up and do it.” The director broke up the fight between us, and gave Estelle specific instructions on what to do: “Stand here, turn, count to three, walk three steps forward, put down the bag, say the line, pick up the bag, turn, walk out the door.”

She agreed to do it, but warned us: “I’m telling you it’s terrible, and nobody’s going to like it.” At the first preview, just to prove it wouldn’t work, Estelle did just as the director had instructed. As she exited, she said to the stage manager in the wings, “Did you see how badly that went? The whole audience was shuffling, and coughing. They were all bored by that speech, that’s how bad it was!” Well the truth was the audience had collapsed in tears, and that noise was people getting out their handkerchiefs. Later, one of Estelle’s friends came backstage and raved about how moved she was. “Oh, I know,” said Estelle. “I told Harvey that speech was a winner.” That was Estelle.

When we transferred the show in 1981 to the Richard Allen Theatre off-off-Broadway, the cast included Joel Crothers, who was on The Edge of Night. Estelle used to tease him: “Mr. Handsome! Mr. Soap Opera! Mr. Rich Guy!” Those started out as great times. Then suddenly Joel got a stomach bug that we all thought was due to a parasite he’d picked up on his last vacation to South America. When the show moved to off Broadway, Joel said he wasn’t well enough to come with us. So another actor, Court Miller, came in. Court would come in to work every day with a new ailment, and we’d all laugh, thinking this man is the biggest hypochondriac of all time. One day it was cold sweats, then stomach problems, then this, then that. Shortly after that our pianist, Ned Levy, brought in this article from a San Francisco newspaper about this newly discovered gay cancer.

We had had no idea. They didn’t even know yet that it was sexually transmitted, and Court had never been to California. But very slowly, it began to dawn on us that Court was sick. It still didn’t dawn on us that Joel had already been sick, one of the earliest cases before it was even an epidemic. So already, in those early days, two people whom Estelle loved had already been stricken with what we would learn was called AIDS.

When we moved to Broadway, our stage manager, Herb Vogler, was sick. We hired an actor to understudy the boyfriend in act two and the son in act three, a young man named Christopher Stryker. And again, another young man Estelle came to adore. Christopher started getting sick, and then people at my other show, La Cage aux Folles, started getting sick.

Torch Song had really become Estelle’s family—and not in that clichéd way that most actors talk about; Estelle yelled at me the way only a mother would yell. I’d have to remind her all the time that she was merely acting as my mother. By the time the show closed on Broadway in 1985, Estelle was out in California, about to begin work on The Golden Girls, and was doing whatever she could to fight the disease. She had been heartbroken not to be cast in the movie version of Torch Song Trilogy, but she was there at its premiere, which became the first AIDS benefit ever held in LA.

Estelle backstage on tour with her Torch Song family, including Jonathan Del Arco (right).

Photo by GERRY GOODSTEIN, Photo courtesy of JONATHAN DEL ARCO.

So Estelle ended up being in the middle of the AIDS epidemic from day one. We were fighting that war very early on. Because this was Estelle’s family. These were her kids. She loved them, and seeing them die, one by one, just destroyed her.

When she got to LA, Estelle settled into a new life as a single woman. She hadn’t let Arthur come to California with her, nor were her two sons there. She lived in an apartment, and hung out with her gay entourage, her “five-fag minimum.”

In 1994, I did a very short-lived series for Witt/Thomas called Daddy’s Girls, which was shot on the same lot, so I got to see Estelle all the time; she was next door doing Empty Nest. I know I found acting in a sitcom very difficult, because during the dinner break between the night’s two tapings, the writers could rewrite possibly the entire script. When you go back out there, you might be doing a whole new scene you’d never rehearsed. They say doing that, it’s like with any other muscle; if you do it long enough, it gets easier. And certainly the other three Golden Girls, Bea, Rue, and Betty, were all veterans.

But Estelle had a different style. Doing a sitcom versus a movie versus appearing onstage is all called “acting,” but they’re all such different disciplines. For an actress like Estelle, in the theater, you would learn your lines, and then have them under your belt so that you don’t ever have to think about them; then you can really act. But unfortunately, that’s not how sitcoms are. And on top of that, Estelle was beginning to have memory issues, and for such an independent woman, that frightened the hell out of her. And then the fear only made the issue worse.

Estelle (center) joins Jenna von Oÿ (left) and Mayim Bialik on crossover episode “I Ain’t Got Nobody” of Witt/Thomas/Harris’s NBC series Blossom, aired February 11, 1991.

Photo by CHRIS HASTON/NBCU PHOTO BANK, via GETTY IMAGES.

Estelle and Rue join Betty on her CBS sitcom Ladies Man, in an episode airing May 19, 2000.

Photo courtesy of CBS via GETTY IMAGES.

Nobody’s ever going to be Estelle to me. With all our fighting and all the other dynamics that went on between us, that was a relationship that was singular in my life. I created Torch Song for her; I created that character for her. I owe her a large piece of my success. When I turn on The Golden Girls now, it’s not for the guest stars. I prefer the episodes where it’s just the four women. I don’t care about the stories either; they’re just bullshit. What you want when you turn on The Golden Girls is to spend thirty minutes with your friends. For me, I turn it on, and get to spend a little more time with Estelle.

AUTHOR’S UPDATE:

After appearing for a year in the Golden Girls sequel series Golden Palace, Estelle proved there was still life in the nearly nonagenarian Sophia Petrillo, bringing the character back to appear in nearly fifty episodes of Golden Girls spinoff Empty Nest. After that show’s demise in 1995, Estelle continued to make sporadic TV guest appearances on such shows as Touched by an Angel and Mad About You. As her issues with remembering lines progressed, Estelle was drawn particularly to voice-over roles, where she could perform with a script; so she voiced a character in an episode of the animated series Duckman, and played a role in HBO’s 1999 animated adaptation of The Sissy Duckling, written by her longtime friend Harvey Fierstein.

Having made a few movies, including Mannequin and Stop! Or My Mom Will Shoot, during the run of The Golden Girls, Estelle landed a few more roles on the big screen, in The Million Dollar Kid in 2000, and, belovedly, as the voice of the grandmother of the title mouse in 1999’s Stuart Little.

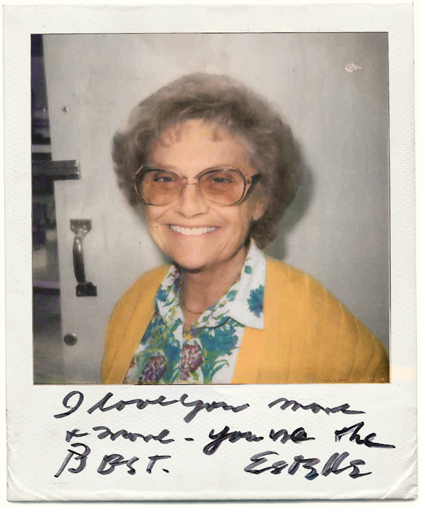

Photo courtesy of ESTATE OF RUE McCLANAHAN, estateofrue.com.

In 1996, Estelle reunited with Betty White and Rue McClanahan, as they played themselves in a hilarious and surreal episode of NBC’s The John Larroquette Show, written by former Golden Girls scribe Mitch Hurwitz, titled “Here We Go Again.” A parody of Sunset Boulevard, in which Betty wants to stage a demented, hours-long Golden Girls musical in Larroquette’s St. Louis busstation, Estelle was Max the butler to Betty’s Norma Desmond. In 2000, Estelle was reunited again with two of her Girls when, visibly frail, she was led through the door by fellow guest star Rue to make a brief appearance in the tag of an episode (“Romance”) of Betty’s CBS sitcom Ladies Man.

By the early 2000s, Estelle had faded from public view, as she battled what came to be diagnosed as Lewy body dementia. Bea, Betty, and Rue all tried to stay in touch, but it wasn’t easy, as the disease took its toll. On July 22, 2008, Estelle Getty, née Scher, died at age eighty-four. The self-described “little girl from the Lower East Side” had moved west late in life, and then made it bigger than she had ever dreamed she could. She is buried in a Los Angeles cemetery, open to the public and fittingly called Hollywood Forever.