WHEN LEGENDARY PRODUCTION designer Ed Stephenson first read the script for Susan Harris’s new high-profile pilot, he knew just the home he wanted to create for the Girls. A decades-long TV veteran and three-time Emmy winner, Ed had worked with Betty White on live TV in the fifties, and later with Bea Arthur and Rue McClanahan on Maude. Now as the in-house designer for all the Witt/Thomas/Harris productions, Ed had a gut feeling that The Golden Girls was going to be a big hit, and wanted to create a lasting environment befitting the show’s four powerhouse stars.

Even before earning his credits in TV, Ed had started his career working in Florida theater. “So he knew exactly what he wanted to do,” remembers Michael Hynes, The Golden Girls’ longtime assistant art director. “He went home one weekend and designed the whole thing, and then we started making a model of the three rooms in the house the pilot called for: the living room, lanai, and Blanche’s bedroom.”

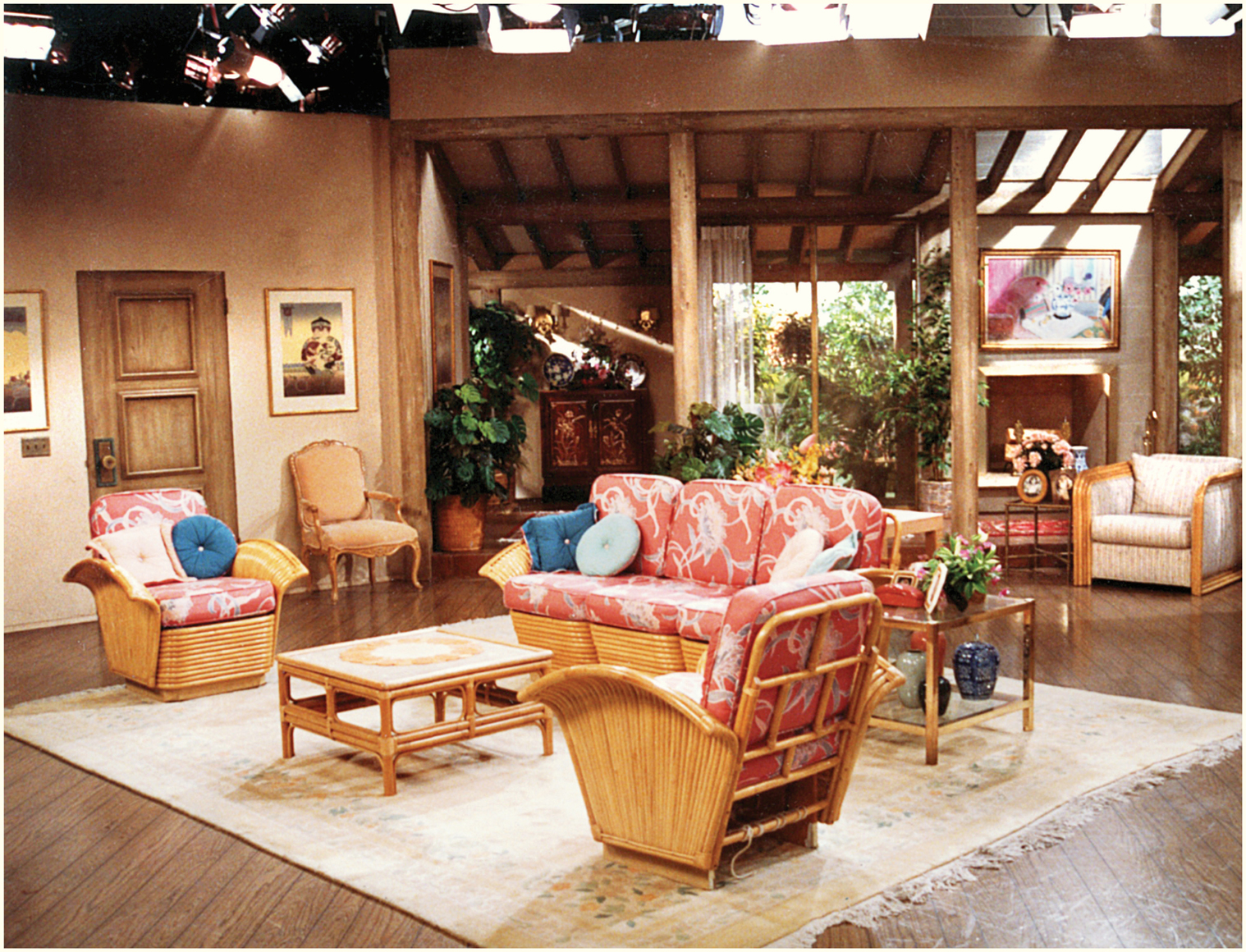

Right from the start, Ed envisioned a certain “Florida look” for the Girls’ home’s interior, explains John Shaffner, the assistant art director Ed tasked with decorating the pilot’s sets. Ed wanted the look of pecky wood, a textured cypress popular in South Florida, for the house’s doors, interior columns, and roofline. Then, it was time for the two to talk furniture. “We realized that each of these women was going to be bringing something into this house. It wasn’t just Blanche’s house now, but a little bit of everyone’s,” John explains. And so, although the living room was dominated by a tropical rattan-style couch, its adjoining end table or console might not match.

For the home’s fabrics and decorative touches, the designers opted for a palette of pastels and softer hues, with occasional pops of brighter color. Then, as John remembers, “When it came time for the set to be installed on the stage, it was so simple. The flooring I had selected was unrolled and taped down. The set walls were put up, and painted all the colors and textures Ed had selected. Prop men moved in the furniture and hung art on the walls, and I finished dressing the set down to the coffee mugs on the kitchen counter.

“The producers came through the next day, and looked at everything, and said, ‘This is wonderful. Thank you very much.’ And that was it,” explains John, who went on to design the iconic looks of Friends, Two and a Half Men, and The Big Bang Theory. “It wasn’t nearly like today, where hand-wringing executives will come to check your progress every day, and say, ‘Are those the throw pillows you’re going to use? Are you sure about that lamp?’”

It Takes a Kitchen

![]()

THEN, EVERYTHING CHANGED in a Miami minute. Not long before the actresses were scheduled to start rehearsing on the sets, Ed’s team received a revised script, complete with new scenes to take place in the Girls’ kitchen. “There had been no kitchen in the original script. But now, right at the last minute, we needed one,” Michael remembers. Luckily, having worked on so many sitcoms, Ed had kept over 150 of his past sets in storage; the Witt/Thomas warehouses were full of rooms previously seen on such shows as Soap, Benson, and It’s a Living. “Ed came back to the office,” Michael recalls, “and said, ‘What do we have in stock?’”

Perusing the company’s inventory, Michael found a kitchen he convinced Ed would work, from Witt/Thomas’s earlier show It Takes Two. “So we took what had been that show’s kitchen and just spliced it right on to the Golden Girls’ living room,” he explains. “We took out the oven area and a couple of cabinets to make it a little smaller, but otherwise that was their wall paper, their shelves, and their plants.” Outside the same kitchen window, instead of a scrim of the glittering Chicago skyline was now an image of sun-dappled Miami palms. And with that, the kitchen that would become iconic as the setting for The Golden Girls’ beloved cheesecake scenes was created, recycled from the remnants of a forgotten show that had lasted merely one season.

Left to right: Helen Hunt, Richard Crenna, and Patty Duke in ABC’s 1982–83 sitcom It Takes Two.

Photo courtesy of PHOTOFEST, with permission of DISNEY NTERPRISES, INC.

With the Girls’ new kitchen installed and ready, the show’s first crisis was averted—temporarily. By their very nature, sitcoms suffer from what Michael refers to as “the proscenium theater problem”: multicamera shows require three-walled sets, much like opened-up dollhouses, which still need to look convincingly like someone’s home. “Life exists in 360 degrees, and theater exists in 180,” Michael explains. “And yet I still have to fit everything in there: stairways, doors, the kitchen. So by their very nature, all sitcoms sets are already contorted.”

Production designers usually devise ways around this issue in their blueprint or modeling stages; but here, the Girls’ kitchen had been added after the fact, creating a ripple effect of other changes that made the layout of the house cease to make sense. “The kitchen created issues no one could ever solve,” Michael admits. For starters, now that the room was established as being off the stage-right end of the living room, where was the access to the Girls’ sleeping quarters?

The team’s solution was to create an upstage hallway, leading back to the bedrooms—but the fix created even more discrepancies. The pilot presents Blanche’s bedroom as being off the upstage-left corner of the living room, and the lanai as entered from a door just to the left of the fire-place; in the series, the lanai orientation would be reversed and its access moved upstage left, with Blanche now bunking off the same hallway as her roommates. Either way, Rose’s room now seems to be in the middle of the backyard. And now, the back exit of the kitchen, supposedly toward the garage, seems to lead right into the area of Dorothy and Blanche’s bedrooms. “We don’t know where the garage is,” Michael admits with a laugh. “All we know is there were minks in there once.”

As Michael remembers, “We said, ‘Well, when we get through the pilot, we’ll fix it’—and then we never did.” And so, throughout the series, sharp-eyed fans remained confused. “We used to get letters on occasion, saying: ‘It looks like when Rose goes into her bedroom, she’s going into the backyard, and I don’t understand,’” he reveals. “And in fact, they were right. But Ed would answer the letters by saying, ‘Just keep watching the show, and you’ll figure it out eventually.’”

Reduce, Reuse, Recycle

![]()

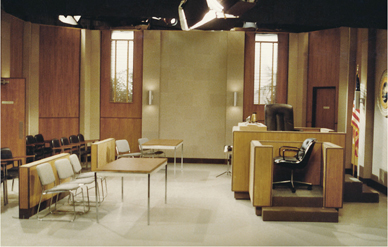

DRAWING ON HIS training in 1950s live TV, Ed Stephenson favored working with “modular” sets, which could be rearranged in different configurations to create various new rooms. By the time of The Golden Girls, Ed was expert at minimizing set-building expenses by recycling old pieces from his previous repertoire. Thus, a teak-paneled courtroom that had appeared on Soap, with a little bit of redressing, now became Golden Girls offices, waiting rooms, and even the apartment of Sophia’s ancient millionaire roommate Malcolm in the show’s fifth-season episode “Twice in a Lifetime.”

Conference room, season 7, “Rose: Portrait of a Woman.”

Courtroom, season 7, “Ebbtide VI: The Wrath of Stan.”

Psychologist waiting room, season 7, “Mother Load.”

Meeting hall, season 5, “Great Expectations.”

Set photos courtesy of the EDWARD S. STEPHENSON ARCHIVE at the ART DIRECTORS GUILD.

Mr. Edouardo’s hair salon, season 4, “Rites of Spring.”

Men’s clothing store, season 4, “Love Me Tender.”

French restaurant, season 7, “Ro$e Love$ Mile$.”

Banquet hall for Bachelorette Auction, season 6, “Love for Sale.”

Hotel ballroom, season 5, “The Mangiacavallo Curse Makes a Lousy Wedding Present.”

Banquet hall for Volunteer Vanguard Awards, season 6, “Sisters of the Bride.”

Hotel ballroom housing the East Miami High Class of ‘52 reunion in season 7, “Home Again, Rose.”

Daughters of the Old South banquet hall, season 6, “Witness.”

Because the Girls attended so many receptions and awards banquets in hotel ballrooms and restaurants, Ed also devised a set he called the Classic Interior, which would pop up on the show again and again. With a selection of French-paneled walls, arches, and Palladian windows connected by individual pilasters, the set could be assembled in various configurations. “Like LEGOs,” Michael explains. So whether they were vying for the Volunteer Vanguard Awards or crashing a high school reunion, the Girls were in differing versions of the same room.

In fact, the Classic Interior proved so versatile that when The Golden Girls’ sequel series Golden Palace ceased production in 1993, Michael opted to keep the set in storage. He has continued to use the set for years, and has even rented it out to other production designers for their shows, donating the proceeds to the Thomas family’s beloved charity, the St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital.

Plywood walls, Michael notes, “last ten years if you’re lucky.” And yet, still viable today, the Classic Interior—“which, in scenery years, is Jurassic”—has proven to be atypically sturdy. In 2012, Michael brought the set to the stage yet again, for an episode of Hot in Cleveland. For a scene in which that show’s four leading ladies attended a hotel fashion show, “I painted it white and put the runway right down the middle.”

Then, just as the scene was ready to go, Michael asked Hot in Cleveland star Betty White if the surroundings looked familiar. “When I told her where the set came from, she flipped out,” he reveals. “She went up and touched it, and got very emotional” to be back again, literally in the same halls where The Golden Girls once stood.

GOLDEN DECOR

KITCHEN

MICHAEL HYNES: Ed had picked out the original kitchen wallpaper, beige with a very small pattern of white dots. Midway through the first season, we changed it. The new paper from Astor Wallcovering had a cross-hatch rattan pattern, then big banana leaves in a darker beige over that, with three colors of green in it as well. The reason we changed it was that in those days, cameras were more primitive than they are now, and things would “flatten out” a lot. So we always looked for wallpaper that added layers and depth.

JOHN SHAFFNER: It was very smart of the writers to make the kitchen a separate room, because it gave them private places to take stories to. The swinging kitchen door allowed the storytelling to go into this other room, where you could have a conversation that wouldn’t be overheard.

MH: By adding on the kitchen, we inadvertently created this little space behind the set walls that became a Golden Girls Bermuda Triangle. It was bounded by the baker’s rack on the bottom, the right side of the hallway, and the left side of the kitchen. Often the ladies would hang out there and study their lines. Plus, it often happened that after the ladies were first introduced to the audience, and the camera would sweep in for extreme close-ups, the producers upstairs would start nitpicking their makeup. So the makeup people waited back in the triangle to fix them. But usually, the ladies would just pretend to get touch-ups. Then they’d come back out, just as before, and the producers would say, “Ah, much better.”

JS: In the pilot, the kitchen table was a round, glass-topped piece from Tropitone, with matching chairs, which we got at a patio store in the San Fernando Valley. Later the chairs remained but the table was a different piece, on a pedestal. But really, post-pilot, the look was all about the tablecloths, which they would change for each episode both to switch up the look and also to complement the ladies’ wardrobe.

MH: Everything in the vicinity of the kitchen table was graffitied by Estelle. She would take a permanent marker and write her lines all over. I kept waiting for her to say a line from a previous episode, but she never did.

MH: The tablecloths quickly became a big deal on the show. Ed always wanted a pattern, but then after dress rehearsal, the producers would often note that the tablecloth clashed with someone’s dress. So we started collecting different options. I bought quite a few on a personal trip to Paris. We ended up with a whole rack of fifty to sixty tablecloths, which we kept right behind the refrigerator.

JS: When the four ladies were in the kitchen, one would take a seat on a stool rather than the fourth place at the table, which would have her back to the camera. Today’s sitcoms sometimes can take cameras deeper into the set, put up a section of wall and do a reverse shot, so that people can sit all around the table. But I think our classic multicamera, proscenium style is more appealing to the audience, because it’s more like going to see a play.

JS: The original piece here was a butcher-block table, on wheels so that it could be moved, which was later replaced with a taller butcher-block kitchen island. The way Ed had laid out the kitchen, the sink was on a diagonal looking upstage, and the refrigerator was on the side wall. It wasn’t a playable kitchen in terms of actually cooking, because all the appliances forced you to face away from the audience. So the kitchen island gave the actresses an area where they could do things facing downstage.

MH: Ed liked using things like the Jell-O molds over the sink to fill the space and cover blank walls. Sometimes we’d go to a design center, and he’d fall in love with things and say, “Let’s put this in the kitchen.” At one point, we added a ceramic keyholder he found, with a caged bird design on it. It was imported from France, and we put it in the space above and to the left of the phone. I still have it today.

JS: Because shows are limited on stage space, Ed had come up with a way to replace the It Takes Two/Golden Girls kitchen set with something else when it wasn’t needed. This area behind the swinging door, where he put the baker’s rack, is all you see from the living room of the kitchen when the swinging door opens, so that the rest of the set could be removed.

MH: The big secret about the Golden Girls kitchen was that there was no oven. The It Takes Two kitchen had had a built-in oven next to the refrigerator, but we’d had to take it out for lack of space. We did still have a range, downstage facing the audience, where we’d sometimes see Sophia cooking. But underneath, it was just a cabinet. We took off the doors and replaced them with a piece of plywood with a handle on it. And the ladies would have to fake like they were taking something out of the “oven.”

MH: We did change the kitchen curtains a few times, but they were always so stiff and not fun. If I could go back, that’s the one thing I would change. Come on, these were four ladies in Florida. At least have flowers or something!

LANAI

JS: For the lanai furnishings, I went with pieces made by Tropitone, which had a wrought iron and vintage look, with forties-era detail.

MH: The original plants on the lanai were plastic, but they were always getting bent up and dusty. So we replaced them with living plants. Ed kept many of them, and to this day, those original plants are all still thriving at his shop.

MH: The lawn beyond the lanai was of course fake grass mats, and the scenery beyond was a giant rented backdrop. It had originally been painted for Frank Sinatra’s 1959 movie A Hole in the Head.

LIVING ROOM

JS: It’s funny how people scrutinize things over time that at the beginning had no significance whatsoever. People often comment on the “exclamation mark” in the grain of the front door. All of the woodwork on the set was not actually carved, but was painted to look grained and textured. Any marks you may see on the front door were just results of the nature of the paintbrush.

MH: This chunky doorknob was a great piece. It was made to go in the middle of a door, so I had to have it rebuilt. I was worried the actresses might have trouble with it, but they never did.

MH: Having done time in Florida, Ed really wanted to capture the distinctive wormholed look of pecky cypress wood, which a scenic artist would recreate with paint. This was before the Internet, and it was hard to find pictures in California to show just what he wanted.

JS: I had done a short-lived show for Witt/Thomas/Harris called Condo, and had purchased this large, Chinese art deco wool rug for the WASPy family on the show. It was yellow and white, and had an asymmetrical design, with a few pink and peach flowers in two corners, and a big border. It had been expensive—about thirty-five hundred dollars in 1983—and it was all the right colors we wanted for The Golden Girls, so we used it again.

JS: Putting this Chinese vase just inside the front door was just a decorative way to take up that space, and to put something with color and shape in front of a flat wall. We had no idea when we put it there that it would soon become part of a plot point, as Blanche’s treasured vase that Rose accidentally shoots and destroys.

MH: I had to have duplicate versions made of this vase, for the episode where Rose shoots it. It was a fairly standard shape, so we had to find a breakaway vase and paint it to look the same. And then of course the next week, the vase was back in the living room again, like nothing had happened.

JS: One of the first things you have to do on a sitcom is identify the big piece for the living room: the sofa. It helps tell you where else you can go with the room’s other elements. I decided I wanted a bamboo/rattan look. So I went to Harvey’s, a popular furniture store now on Beverly Boulevard in LA, which was known for carrying the Florida look, as it was being called at the time.

I chose this piece because, although most rattan couches tended to have flat arms, this one had more of a unique, fan shape, which I thought was more feminine. The couch was actually made out of sectional elements, so we had to wire them together. Then, we tested several color palettes of fabric to cover it with, and gravitated to the orange/peach color, because it also went with the paver tile linoleum floor. The couch and its two matching chairs looked great on-screen, but they did create some issues for the wardrobe department, because they clashed with so many things. So we kept a constant array of throw pillows on hand, to create more of a neutral background between the ladies’ outfits and the couch.

JS: Just a few years ago, I ran into Harvey’s owner, Harvey Schwartz, at an event, and said to him, “You’ll never remember this, but I bought the sofa for The Golden Girls from you.” And he said, “You have no idea how many of those I sold because of that!”

MH: Each Saturday, we’d change the sets over for the next show. One day, we were goofing around, and one of the prop guys put a lampshade on my head, and took a picture. They decided that Polaroid should go on the set, so they framed it and put it right near the sofa. It sat there for three or four seasons.

MH: The pilot had a different coffee table, a carved square piece in dark wood—but we replaced it immediately afterward with this large square rattan model.

JS: Today, any photograph, painting, or illustration you put on a set has to be legally cleared with the owner of the image. Back in 1985, we had no restrictions—but still, it was hard to find images in prop houses that worked, and that hadn’t been used too much on other shows. That’s where Ed Stephenson was a very clever businessman. He amassed a very large collection of two-dimensional and sometimes sculptural works, and opened a business renting works to The Golden Girls and many other shows. His shop, the Hollywood Studio Gallery, is still there on Cahuenga Boulevard today.

MH: Ed wanted the fireplace to capture another classic Florida look: cut coral was literally mined from reefs and cut into blocks. In our case, our scenic artist used paint to capture that same interesting natural texture.

MH: Ed Stephenson had a maxim: you must always design depth to a set, but do it in such a way that the director can’t really stage anything there—because if you stage something back there, against a flat wall, there goes the depth! Ed deliberately wanted to trap the action in the downstage area, which is where all multicamera scenes happen anyway. And then he made sure there was space upstage way behind the couch with a slanted roofline and fireplace that they wouldn’t be able to use.

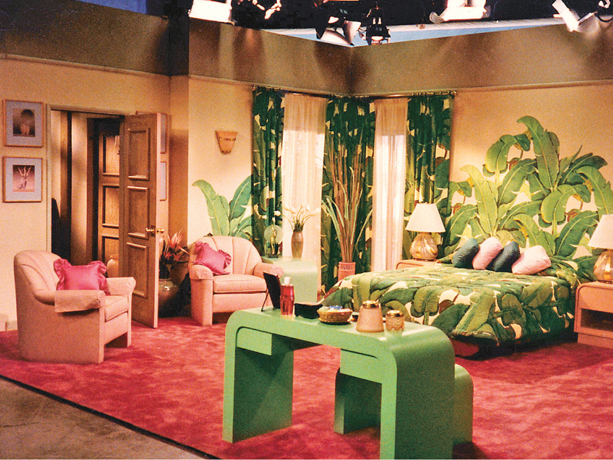

BLANCHE’S BEDROOM

JS: Ed absolutely knew what he wanted to do with Blanche’s bedroom walls, without a moment’s hesitation. He asked me to find the big banana-leaf print wallpaper from the Beverly Hills Hotel. We cut it out along each leaf, and glued each individually to the wall. Then, we didn’t even have a headboard made. Instead, to continue the pattern right onto the bed, we had a double-sided, reversible bedspread custom-made to match the wallpaper. That was not cheap. In 1985, the fabric cost over fifty dollars per yard, plus the labor. Between the shooting of the pilot and the series, I was nervous the expensive bedspread would get lost. So I took this bedspread home—and used it on my own bed all summer.

DOROTHY’S BEDROOM

MH: I used to go to the department store Robinsons-May’s outlet store in Panorama City, California to look for cheap sofas and furniture, and that’s where I found this great pair of cabinets for Dorothy’s room, to put on each side of the window. They had lots of little drawers, and I got a great deal on them. I wish I had them! They ended up in the Warner Bros. prop collection, and so I’ve used them again on other shows since.

MH: This gray rattan desk in Dorothy’s bedroom came from a big design showroom in the Pacific Design Center in Los Angeles. It cost a fortune—but by that point, the show was printing money, so the producers didn’t care.

ROSE’S BEDROOM

MH: I got Rose’s bedroom furniture for cheap at Wickes Furniture, a chain home furnishings store, somewhere in the San Fernando Valley. They had a lot of pieces that were a more modern take on rattan, so I bought a lot there.

SOPHIA’S BEDROOM

MH: Our general idea for Sophia’s room was to make it look like some of the pieces had been in her home in New York, but had been put in storage when Dorothy put her in Shady Pines. Her bedroom was the smallest of the four in Blanche’s house; Edward Stephenson figured the other three ladies had already taken all the biggest rooms before Sophia moved in. I put in some white “antiqued” finish pieces, because that was something many women of Sophia’s generation bought in the 1960s and then hung on to forever. And I thought the marquetry vanity had an old-world feeling Sophia would have liked. The headboard and much of the rest of the furniture came from Wertz Brothers Used Furniture in Hollywood, a source we used often. But Sophia did have one designer touch in the room: her wallpaper, from Albert Van Luit.

The Golden Girls house in Brentwood, CA, in 2014.

Different on Outside Same on Inside

![]()

WHEN ASSEMBLING A new sitcom, choosing establishing shots—locations to photograph that represent the outsides of the characters’ homes—is a task usually saved for last. It’s thankless work, because by definition, no existing building’s exterior will ever align perfectly with a multicamera show’s three-walled sets. “There isn’t a show on television where you’ll ever see an exact match,” Michael Hynes explains. “So you can’t become overly anxious about it.”

Seen here in March 2001, the replica Golden Girls house at the Disney-MGM Studios theme park at Walt Disney World featured landscaping, and even the house number 245, recreated to match the original in Brentwood, CA.

Photo courtesy of FRANK DeCARO, Photo by JOSEPH TITIZIAN.

So, for the Girls’ house, the production team focused on finding a structure with at least the same overall “tone:” a low-slung house, with an overhanging roofline and surrounded by lush green shrubbery. Then, after the ideal candidate was located in the Brentwood section of Los Angeles, Ed tried to match the feeling of its entryway by enclosing the Girls’ front doorstep inside an alcove, covered with vines of blooming bougainvillea.

In the middle of the Girls’ run, however, Witt/Thomas’s production partner, Disney, approached the show with an idea. As the company prepared to open its MGM theme park within Disney World in Orlando, the park’s designers planned one attraction to be an exterior street where sitcoms or other TV shows could be shot. After taking extensive photos of the real Golden Girls house in Brentwood, the company rebuilt the house in Orlando from scratch—and not just a façade, but a full, three-dimensional building.

“Disney wanted to be able to say honestly that the new house was ‘as seen on TV,’ on The Golden Girls,” the show’s associate director Lex Passaris recalls. And so for the remainder of the show’s episodes, some of the establishing shots—particularly specialized footage such as a special-effects shot of the house being pelted by hurricane-force winds and rain—were captured in Orlando. But don’t go looking to park in the Girls’ Florida driveway today; in 2003 the house, along with a similar structure built to represent the exterior setting for Golden Girls spinoff Empty Nest, was razed, as the MGM park knocked down its “Residential Street” in order to make room for a new arena for the extreme stunt-show attraction “Lights, Motors, Action!”