The blade itself incites to deeds of violence.

—HOMER, The Odyssey

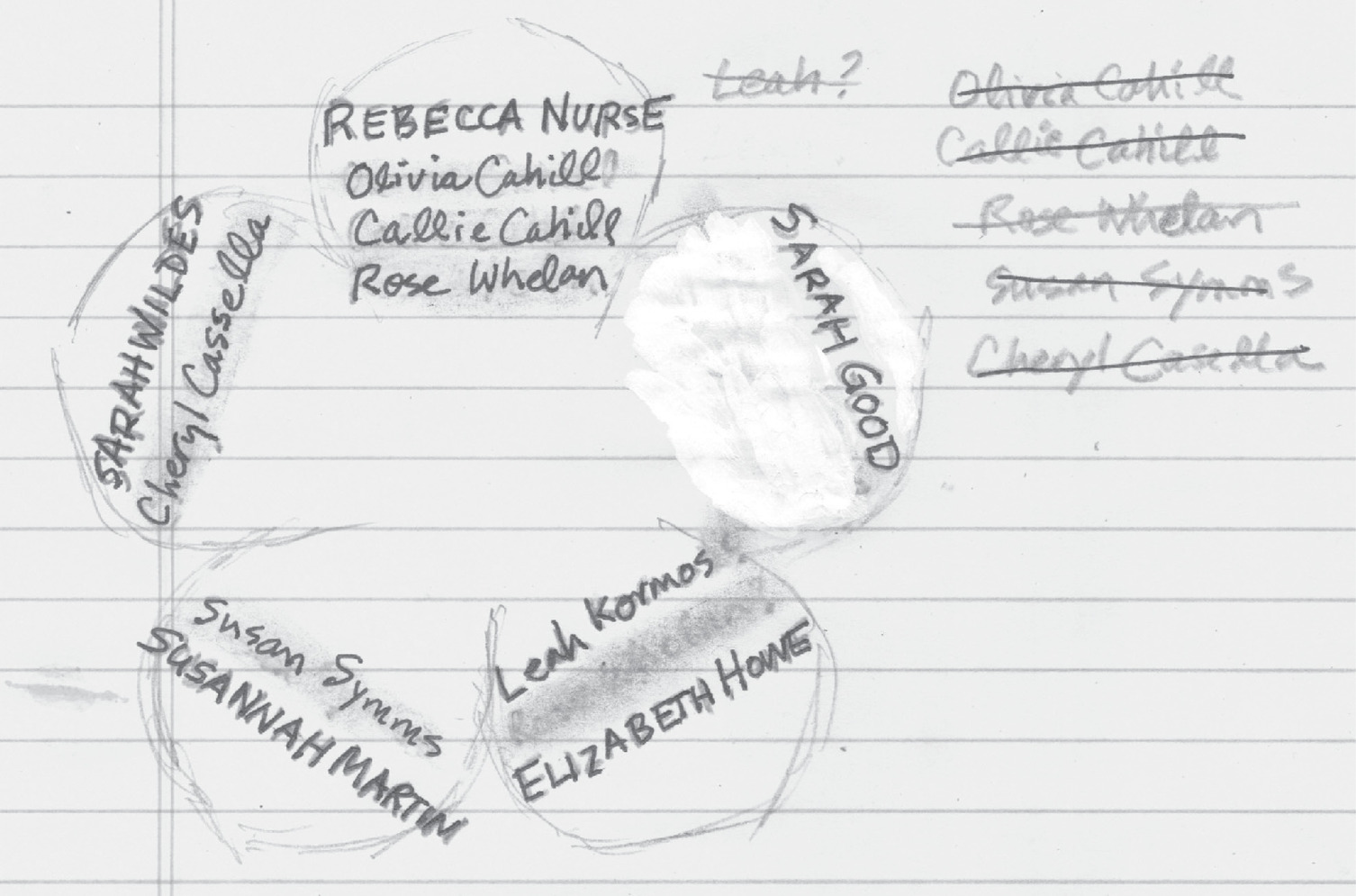

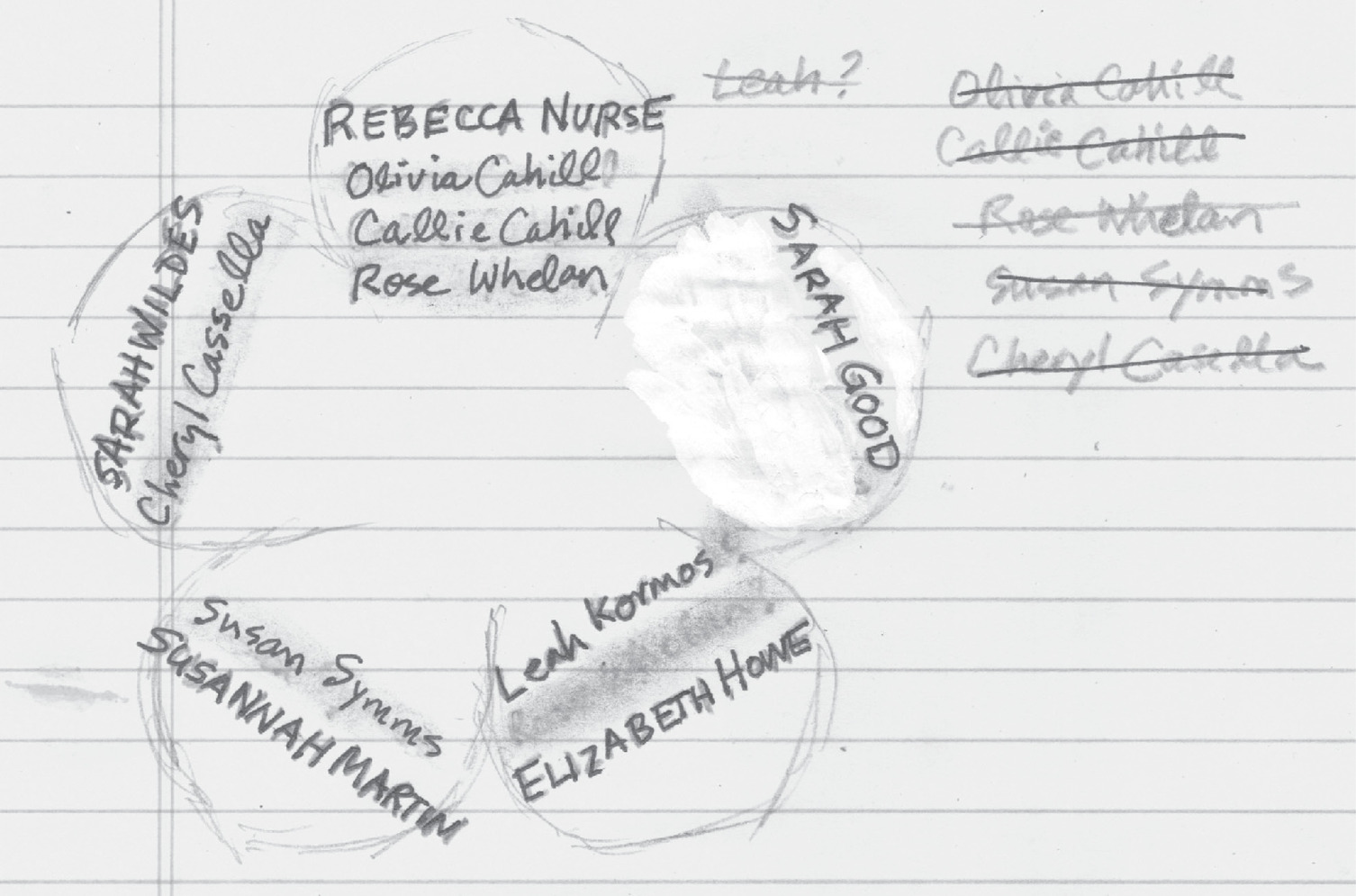

“Leah Kormos isn’t related to Sarah Good. She’s related to Elizabeth Howe.”

Mickey’s news didn’t come as a complete shock. For quite a while now, and certainly ever since he’d talked to her sister, Rafferty had become certain that Leah was no longer the primary suspect. But if Leah wasn’t related to Sarah Good, if she wasn’t the fifth petal, then who the hell was?

He’d already erased Rose’s name from under Good’s. He’d made Mickey recheck the others against their ancestors, not with Sarah Good this time, but confirming the corresponding names and ancestors now written on each petal. They’d checked out; the positions were right. Now he erased Rose’s name from Elizabeth Howe’s petal, inking in Leah’s instead. Finally, he removed Leah’s penciled-in name from under Sarah Good’s, but the eraser smudged the paper so badly it would have been impossible to add another name, even if he had one. He found an old bottle of Wite-Out in the desk drawer and painted the petal until it became as white as Susan Symms’s albino skin, which made it stand out even more. Four of the petals now had correct links from ancestors to women in modern times. All that was missing was the name of the descendant of the fifth petal, Sarah Good’s, which was now more mysterious than ever.

One thing was beginning to become obvious. There hadn’t been just one petal missing from the blessing that night on the hill. There had been two people who were absent that night: Leah Kormos and someone else.

“No luck?” Towner said, looking over his shoulder at the blank white petal.

“I’m at a loss,” he said, shrugging. “I know each of the girls was related to one of the executed, and that Callie said Rose was related to more than one of them. But Rose wasn’t related to Sarah Good, Mickey has already established that.”

“I’ve been thinking about that,” Towner said. “I seem to remember hearing that Rebecca Nurse had a sister who was also accused. So I just checked it out online. Actually, she had two sisters who were accused of witchcraft, and one of them was executed. Not on July nineteenth, though.”

“Rose never told Callie it was on July nineteenth, just that she was related to more than one of the executed. I guess that means Callie and Olivia were also related to more than one.”

“That still doesn’t tell you who the fifth petal was.”

“There was someone else on the hill that night. Someone who was related to Sarah Good. Was there another Goddess we don’t know about?”

Towner was silent for a long moment. “Why does it have to be a woman? Didn’t the blessing simply require a descendant?”

“True enough,” Rafferty said. It wasn’t as if the thought hadn’t occurred to him, but that he was hoping it wasn’t a possibility. If it were a man, there were so many as yet unrevealed suspects that Rafferty might have to check half the population of Salem before he found the one he was looking for.

He’d already told Callie that he didn’t think it was Leah who had killed the Goddesses. “Leah got pregnant, Callie. That was the rule she broke.”

He started looking for another suspect. And the place he started was the love letters.

If Rafferty had been moved by the youthful romanticism of the letters when he’d first discovered them, reading them now had the opposite effect. They were very personal, and he found himself embarrassed, so much so that he got up and closed his office door. Each letter contained a description of the sender’s fantasy and how the Goddesses had fulfilled it in a way he had never dreamed possible. These weren’t love letters per se. They were thank-you notes. That any man had put such personal details down on paper amazed him. That one man had actually signed his letter with his full name was even more astonishing. If the young women weren’t witches, they were certainly bewitching.

Rafferty looked up the number and phoned the man who’d signed his letter.

“I spoke to you people about this years ago,” the man said.

“We people, as you so politely refer to us, have been replaced by newer people. Which means drop your attitude because you’re going to have to talk to us again.”

“Okay,” the man agreed, put in his place. “But not at my house. I’ll come to you.” He lowered his voice. “I don’t want my wife to know.”

The man, Donald Booth, was in his midfifties, a successful lawyer and married for the second time. Once he started talking about the Goddesses, he became energized, much less reticent than Rafferty had expected.

“It was only one night, but it was the most memorable of my life. It wasn’t just the number of them. There was something magical about those girls.”

Rafferty didn’t react.

“As far as the trouble they caused around town,” he went on, “it wasn’t the sex. It was the obsession.”

“Can you elaborate?”

“The night I was with them, guys showed up at the door twice; each time they were begging to see the girls again, but the girls refused. The thing was, they would only consent to be with you the one time. Then you had to write them a note. Those were the rules. There were exceptions to the one-night thing, I heard, but I wasn’t fortunate enough to be one of them.”

“Do you know who the exceptions were?”

“I don’t.”

“What about the two stalkers who showed up while you were there?” Rafferty asked. “Did you know them?”

“I wouldn’t call them stalkers,” the lawyer said. “I’d describe them as…moonstruck. It’s difficult to be possessive of four women at the same time.”

“Four? Are you sure of the number? It wasn’t five?”

“You tend to remember the number when you’re being seduced by four women,” he said. “Even if you’re high as a kite.”

“High on what?”

“Pretty much anything we could find,” he said. “Grass, X, ludes, coke, scotch. Everything was around in those days. Anyway, you couldn’t possess those girls, even if you wanted to.”

“Not sure who’d want to take that on,” Rafferty said, meaning it.

The man laughed knowingly. “I think those guys just wanted another night with them.”

“Is that what you wanted?”

“Absolutely. Why not? I was single at the time. And hey, it was the best sex I’d ever had. But it wasn’t just sex. I mean it was, but it was more than that. It was a transcendent experience.”

Rafferty paused but didn’t comment. “Did you ask to see them again?”

“Several times. But they declined, which was probably a good thing. I might never have finished law school if they had said yes.” A shadow of sadness passed over his face. “Terrible, what happened to them.”

“It certainly was.”

“There’s a double standard, don’t you think? If men had behaved like they did, a group of them with one woman, it would be called gang rape.”

“Are you saying they forced themselves on you?”

“No, not at all.”

“Not against your will, then.”

“Hardly.” The man laughed.

“Then it’s not gang rape, is it?” Rafferty saw too much of that these days. Cell phone postings with drunken young women and alcohol-fueled men.

“No, that wasn’t the case with the Goddesses. But make no mistake, they were definitely in control.” He paused. “At least they were for a while.”

“Did you know any of the other men they were involved with?”

He shook his head. “They were actually pretty discreet about their conquests.”

Rafferty thanked him, and the two men shook hands. The lawyer started toward the door, then turned back, remembering something. “There was one guy who was at the house quite a bit,” he said. “I only know this because I heard them talking about him. He was the one who painted their portrait, the one on the wall. That one might have been a stalker.”

“Who was that?”

“H. L. Barnes.”

“Any relation to Helen?”

“Her husband.”

Rafferty did a double take. H. L. Barnes was Helen’s husband? He’d never imagined Helen had ever been married. Everything about the woman said spinster.

“But you won’t be able to talk to him.”

“Why’s that?”

“He’s dead.”

Rafferty had never been inside Helen’s Chestnut Street house. It seemed more museum than home, with chinoiserie and Federal-style pieces crowding every available space. The architecture featured the understated elegance of the Loyalists, in particular Samuel McIntire, whose woodworking defined the entire eponymous historic district. From what Rafferty could tell, nothing but the reproduction rotary phone in the front hall was less than two centuries old. Definitely old money, he thought.

He had been directed to wait for her in the parlor and had been sitting for twenty minutes on a chair that was far too delicate for his large frame, trying not to move for fear of breaking the damned thing.

“It’s four o’clock. May I offer you some tea?” she asked, arriving at last, her springer spaniel at her heels. The tray arrived as she spoke.

“Yes, thank you.”

She directed her housekeeper to leave the silver service and poured the tea herself, asking how he took it, then handing it to him. He could not get his fingers to grip the delicate flowered cup, and so he held it with two hands, sipping as she did, putting it down on the side table carefully so as not to rattle the saucer.

He had the childish urge to brag to her that he and Towner lived in a more elegant mansion than this one, down on Washington Square, that it was in the Jeffersonian style, had twin marble fireplaces and a hanging spiral staircase, and that if and when he took tea at all, it was at the tearoom, where they brewed a better cup. Nothing she could do to intimidate him would work.

“Your message said you wanted to talk about my husband,” she said, her expression pinched.

“H. L. Barnes,” Rafferty said. “Until recently, I had no idea you had a husband.”

“I suppose you also learned of his demise?”

“I did.”

“Then you should know that poor Henry wasn’t well. He is the last person I want to speak ill of.”

“I would never expect you to speak ill of anyone,” Rafferty said. Yet somehow it seems to happen with regularity.

“You have questions for me?”

“I have several,” Rafferty said, handing her the photograph of the portrait Henry had painted on Rose’s wall. Underneath the portrait, he had signed his initials: H. L. B. She looked it over briefly, a pained but not surprised expression on her face. She’d seen the photo before, he realized. She handed it back to him and walked to her desk. “There are different kinds of bewitchment,” she said, her tone implying that he, of all people, should understand what she meant.

Rifling through papers in a hidden compartment, she returned with an envelope, stamped and hand lettered. Rafferty could see from the condition of the paper that it had been reread many times. She handed the letter to him. “Keep it,” she said. “I’ve seen quite enough of it for one lifetime.”

My Dearest Helen,

I cannot go on.

Forgive me…Henry

Rafferty sat for a long moment. “Why in the world did you insist on the exhumation? You must have known it would bring attention back to Henry and yourself—”

“Henry didn’t kill those girls.”

“I haven’t suggested he did. But by insisting we reopen this investigation, you identified yourself and your husband as prime suspects.”

“Not my husband, certainly.”

“Why not?”

She handed him the envelope. “Look at the date.”

The letter was dated October 13, 1989, a few weeks before the murders.

“My husband was a very sick man, Detective Rafferty.”

He was surprised by the empathy he heard in her voice.

“That letter was sent from a hotel in Boston. He was kind enough not to take his life here, knowing I would never have been able to stay in the house with the memory.”

“I still don’t understand your motivation, Helen,” Rafferty said. “Why did you call attention to yourself this way? Why cause yourself trouble? As well as a probable scandal—”

“She killed my grandnephew.”

“You know that’s not true.”

“She confessed to the crime!”

“There was no crime.” Rafferty took a deep breath before continuing. “You know as well as I do, Helen, that your nephew died from a cerebral hemorrhage as a result of narcotics.”

Helen sat for a long moment before she replied. “The girls she took in and protected, those so-called Goddesses, killed my husband. Rose may not have done it directly, but make no mistake: Rose Whelan was responsible. My husband had AIDS, Detective.”

Rafferty stared at her.

“Given to him by those girls at the brothel Rose Whelan was running over on Daniels Street.”