When a stream of revenue large enough to finance an armed group cannot be extracted by any legitimate nonviolent enterprise, the businessmen who rise are by their very nature violent and illicit: they are warlord entrepreneurs.

It would be easy to dismiss these actors as phenomena of the edges, like cracks in neglected sidewalks, but they are really phenomena of failure, and failure is everywhere, once you let yourself see it. The cracked sidewalks are not only far away in countries with UN missions, they are in wealthy countries too, in those pockets where old industries died, leaving deskilled wastelands. In a stable, competitive environment, business eats the lunch of prospective warlord entrepreneurs. Vast capital assets, high trust networks, and deep human resources will always win against the comparatively small and disorganized warlord entrepreneur’s tenacious little businesses. But things fall apart, the center cannot hold, and a certain somebody and friends do business where the state, IBM, and Walmart have all failed. Just as scrub comes in shortly after great oaks are felled, so our warlords are first through any available gap.

What is it that fails, giving the warlord entrepreneurs room for maneuver? Some say rule of law. Others, property rights or the state itself. I say it is accountability that fails: when nobody is willing to go to the wall for what is right, the failure that counts has started. The gap between no profit for business and loss of state legitimacy is filled with corrupt authorities. A warlord entrepreneur’s customers were first turned away by regular service providers, then alienated from the state. A customer should be able to get a legitimate visa, but the office is closed—except for bribes. A container ship is leaving on Thursday, but the available space is unavailable because there is nobody to inspect the shipment for arms until Monday. This area is meant to have regular police patrols, but after nine in the evening they are hardly seen.… The warlord entrepreneur is always last. It is the place you go when there is nobody else—the loan shark, the protection racket, the forged travel papers.

America’s past warlord entrepreneurs are lionized. The Mafia and Vegas, baby, their town. During Vegas’s heyday, the Rat Pack fluidly bridged acting, music, politics, activism on race issues, and organized crime. Nobody doubted that Frank Sinatra was tight with the mob; it was part of his charm, all part of the glamour. To this day, Vegas provides a service: vice. Once, that vice included alcohol, but now it is just drugs and prostitution. For Vegas to exist, the state had to turn a blind eye to warlord entrepreneur operations there—not just for a few years, but for decades. In this crisis—a failure of values—comes the inevitable transfer of legitimacy from the state to warlord entrepreneurs. In your mind’s eye, meet Big Joe, who could be from anywhere. He genuinely cares about your problem, as he is personally responsible for your money and for the merchandise. He will take personal responsibility for outcomes, unlike all other actors involved in the situation, who hide behind job titles, policies, and badges. Everybody else has a policy. Warlord entrepreneurs have obligations. Everybody else has a hierarchy. Warlord entrepreneurs are accountable to the situation. Our bureaucracies create an enormous gap between the laudable goals and the public-relations front and the actual dysfunction and callousness of front-line operations. Dragons grow in this gap.

Every place a promise is made and then broken, the state loses legitimacy. Everywhere legitimate business will not do business, black-market business thrives. Cannot get a wire transfer from Guyana to Ghana to pay for your website, because the banks charge a fortune or simply will not send the money? That is just fine—use bitcoin like normal people. Cannot get a MasterCard in Liberia? Use a prepaid debit card from a foreign bank through your cousin in New York—and refill it by acting as a smurf for structured payments when they are laundering money. Every barrier to normalized business, to the smooth and effective functioning of business as usual, creates a shadow. In the deep shade, those dragons mature.

The little man who fixes visas sprouts teeth and becomes the criminal logistics magnate of a war-torn city. His protection racket works, because this is not Iowa and his men are accountable. Five AK-47s and an old Toyota become civilization’s darning needle, holding together enough to let life go on just one more day. Everybody knows it’s wrong, but in these times, what else to do? The budding warlord entrepreneur delivers when nobody else can. Pretty soon there’s a vehicle fleet and a pool of capital and an operations base with a small training and recruitment program. If the guy’s smart, he’ll clean up a little and sign on with the State Department after the army leaves, providing logistics and security for programs with lax oversight. How often has this happened in Iraq and Afghanistan already? The answer is: always. Once the social fabric is torn, the warlord entrepreneur is like the clotting blood, the scab forming over the wound. It is a messy healing process, and infections can be terminal to the rule of law. But without the clean, smooth function of the legitimate system—without unbroken skin—these problems are inevitable. And once a situation has mostly scabbed over? The smart, logical thing to do is to mainstream the previously warlord entrepreneurs as businessmen who did rather well during the crisis period. That’s the right thing to do, isn’t it? I mean … sure, we all know this guy had a past, but we can leave him out there in the cold, running a criminal syndicate, or we can get him to focus on his legitimate businesses … the least bad of the bunch … and pretty soon this kind of thinking puts the Taliban back in charge, because, you know, they’re tough on opium production.

How did we wind up in this mess? The answer is disturbingly simple: we lost our legitimacy at the goat rodeo.

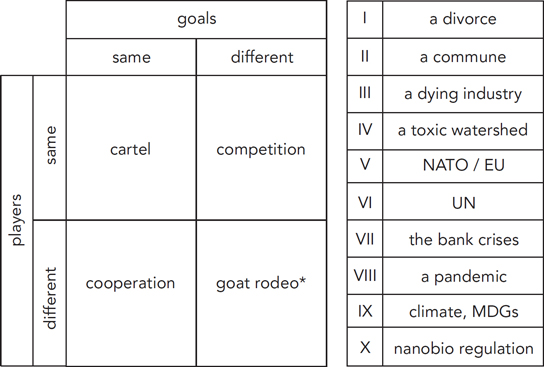

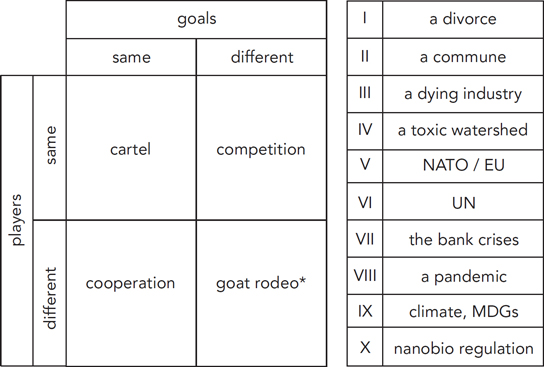

Figure 1.1 Left, players versus goals in goat rodeo; right, levels of goat rodeo complexity.

The term goat rodeo is taken from aviation, where it means a situation in which several impossibly difficult things have to simultaneously go correctly for there to be any realistic chance of survival. The term also refers to the messy Texas practice of having small children practice their lasso skills on goats, as a safer alternative to full-sized cattle. For our purposes, a goat rodeo occurs when a committee sets out to solve a problem but is composed of individuals with different goals who are representing different classes of organization or agency. A typical post-disaster goat rodeo might include a couple of people from State Department or another government agency, some NGO reps, a few local partner organizations, and a few people from national monopolies for water and electricity, plus the host-state representatives, of course. Lacking a shared competitive framework or genuinely shared goals, the situation inevitably devolves into failure. Cooperation is impossible, because people want different things, and competition is implausible because the actors involved have entirely different rule sets. For larger problems, increase the size and diversity of the group until no action is possible at all. The size of the failure can be estimated using the scale above.

Again and again, chains of command and responsibility are abrogated in complex, shared governance arrangements that produce no responsible parties when failure comes. From no-fault divorce through to Kyoto, Copenhagen, Cancun, and the Millennium Development Goals, we plead that none of us are responsible, because all of us are. Warlord entrepreneurs eat this for breakfast. Every time the world of the white picket fences or the blue helmets of peace and justice fail to deliver on their promises, every time they burn people in internecine bickering over different priorities in the crisis, legitimacy bleeds out. Every time the bureaucrats do the wrong thing for the right reasons—or, more commonly, simply fail to do anything at all—a little more of the lifeblood of our civilization leaks out.

That’s where the warlord entrepreneurs are coming from: it’s us, screwing up one day at a time. American drug policy burns half of South America. European immigration policy ensures human trafficking remains intensely lucrative. Uneasy collusion in Africa is good for business, but that’s not just legitimate business, it’s every dirty scam going—from diamond mining to over-advertising breast-milk substitutes in places where we know there’s no clean water.

You have to wonder how the world runs at all when we, the people who are supposed to be governing, supposed to be helping, cannot get our acts together. Every time we quietly complain about the bureaucracy, about lax decision making, about human resources, about inadequate briefings and vague political goals, that’s your reminder that we are part of the problem, not just vendors of the solution.

My advice is to prevent goat rodeos: permit only a single class of player to participate, or fix the goal and bar those with alternative objectives.