2

Falstaff among the Minions of the Moon

In the long cultural tradition that has sought to relate Elizabeth I and her most talented subject, Sir John Falstaff plays a starring role.1 Anecdotal evidence suggests that the queen intervened repeatedly in Shakespeare’s shaping of this character. So, according to his eighteenth-century biographer Nicholas Rowe, Shakespeare wrote The Merry Wives of Windsor (1597) because Elizabeth “was so well pleas’d with that admirable Character of Falstaff . . . that she commanded him to continue it for one Play more, and to shew him in Love.”2 A previous generation of scholars used this posthumous “tradition” of royal interference to speculate that the inconsistencies between Falstaff in The Henriad (1596–99) and his “impostor” in The Merry Wives of Windsor resulted from artistic compromises made to an unperceptive royal command.3 We might consider these stories as evidence of a different sort. Regardless of their veracity, anecdotes like Rowe’s bear witness to a vestigial connection between the Virgin Queen and Shakespeare’s fat knight in his aspect as a senescent lover. Although recent critics have shown little interest in this association, Falstaff does introduce himself as one of “Diana’s foresters, gentlemen of the shade, minions of the moon . . . men of good government, being govern’d, as the sea is, by our noble and chaste mistress the moon, under whose countenance we steal” (1 Henry IV, 1.2.25–29).4 The old man’s fondness for such euphuisms is no accident; a web of references binds Shakespeare’s plump Jack to Elizabeth’s “minions” and “men of good government” as they were described in antigovernment tracts or represented in John Lyly’s Endymion (1588)—especially the greatest minion of them all, Robert Dudley, Earl of Leicester. Shakespeare’s Falstaff is, among many other things, a vehicle for thinking about the sexual and generational transgressions of the late Elizabethan court.

The word “minion” referred to the male favorites of sovereign princes.5 Given the prevalence of the moon cult in the 1590s, Falstaff’s opening invocation of Diana invites audience members to consider his relationship to Elizabeth I. Although David Scott Kastan argues that Falstaff’s self-description does not signal “a submission to authority but an authorization of transgression; he serves not the monarch whose motto . . . was ‘semper eadam alwaies one,’ but only the changeable moon,” the moon cult allowed for and indeed celebrated the paradoxical concept of constancy-in-change.6 The eponymous hero of Endymion, a source for Merry Wives, defends his beloved Cynthia against charges of inconstancy, for example, by praising her ability to wax and wane while keeping “a settled course.” Elizabeth embraced the identification, and had herself portrayed as Cynthia in the famous Rainbow Portrait (ca. 1600; see figure 6). The moon’s properties helped court writers portray a queen who claimed constancy, but whom they perceived as an agent of transformation. Most famously, Sir Walter Ralegh used lunar imagery to describe Elizabeth’s adulterating effect on his watery speaker in “The Ocean to Cynthia”: a change in “Belphoebe’s course” here converts the smooth “ocean seas” into “tempestuous waves” there.7 When Falstaff compares himself to a sea, influenced by his “noble and chaste mistress the moon,” he identifies himself, and his transgressions, with the men about the Virgin Queen.

As a royal favorite “fat-witted with drinking of old sack” and given to taking “purses . . . by the moon and the seven stars,” Falstaff evokes the picture of the “moon’s men” (1 Henry IV, 1.2.2, 14, 31) not just as it was drawn by adherents of the court but also as it was drawn by its most assiduous detractors. In 1584, the authors of Leicester’s Commonwealth had asked that Elizabeth grant their “lawful desire and petition” to try Leicester in court, because of the earl’s “intolerable licentiousness in all filthy kind and manner of carnality,” and because he was guilty

of theft, not only by spoiling and oppressing almost infinite private men, but also whole towns, villages, corporations, and countries, by robbing the realm with inordinate licenses, by deceiving the crown with racking, changing, and embezzling the lands, by abusing his prince and sovereign in selling his favor both at home and abroad . . . in which sort of traffic he committeth more theft oftentimes in one day than all the waykeepers, cutpurses, cozeners, pirates, burglars, or other of that art in a whole year within the realm.

The earl, the authors opined, was a figure of misrule who should be arraigned under the same “laws” that Elizabeth used “daily to pass [judgment] upon thieves.”8 Cardinal Allen concurred, qualifying Leicester’s military activities in the Netherlands as “publike robberies,” and arguing that under the earl’s leadership English soldiers had become “companions of theeves and revenous woolves: and publike enimies of al true Kinges and lawful Dominion.” From the perspective of Elizabethan dissidents, the queen was not a “noble and chaste mistress” but a changeable moon, a monarch who had countenanced the multiple robberies of her “amorous minion,” the “cheife leader” of her “wicked and unwonted course of regiment.”9

By echoing these attacks on the queen’s favorite while showing us an unruly favorite in the company of his prince, the second scene of 1 Henry IV positions its audience to think about the loaded topic of monarchical judgment generally and Elizabeth I’s judgment more specifically. Machiavelli, who was in the revolutionary business of defining the criteria by which one might judge princes, held that “the first thing one does to evaluate the wisdom of a ruler is to examine the men that he has around them.” Thomas Blundeville agreed that “the sufficiency of the manne” was an accurate gauge of “the choyse of the Prince.”10 Falstaff, well-versed in politic authors, endorses this logic when he claims that “it is certain that either wise bearing or ignorant carriage is caught, as men take diseases, one of another; therefore let men take heed of their company” (2 Henry IV, 5.1.75–77). Under such conditions, the “Inclination of Princes to some men, and their Disfavour towards others” might indeed become “fatal,” as William Camden averred, in reference to the great favor that Elizabeth I showed the Earl of Leicester.11 Because “mignonnerie” captured “the straying king personally,” Laurie Shannon thinks it “posed a constitutional conflict” for royal advisors and for “the monarchy itself, as embodied in a king who always has the capacity to act ‘unkingly.’”12 A royal favorite reputed a thief, a drunk, and a lecher was also “fatal” in that people might be persuaded the monarch’s lack of judgment offered “just cause” for rebelling, when subjects technically were, as the pro-government pamphlet A Briefe Discoverie of Dr. Allen’s Seditious Driftes (1588) insists, “private men, and subjects, and therefore can have no lawfull authority . . . to judge.”13

This pamphlet describes the “infamous libels” aimed at Leicester, examined in the previous chapter, as part of an innovative assault on Elizabeth I’s prerogative. The author’s fear that “private men” might arrogate to themselves the place of “judge, corrector, and executioner of Iustice” substantiates Curtis Perry’s claim that “debates about court favoritism” laid “the groundwork for larger transformation of the kind theorized by Habermas.”14 Shakespeare’s contemporaries were aware of these changes, even if they lacked the critical vocabulary to describe them. Habermas defines the bourgeois public sphere, which he sees as emerging in the eighteenth century, as constituted of “private people come together as a public” to engage “in a debate over the general rules governing relations”; what is at stake is in part the rights of the private subject to pass judgment on the sovereign.15 The development of a public sphere had roots in earlier phenomena, including Machiavelli’s secular approach to historiography; according to Michel de Certeau, “When the historian seeks to establish, for the place of power, the rules of political conduct”—like those that govern the selection of political advisors—“he plays the role of the prince that he is not.”16 De Certeau’s metaphor imagines this as a form of theatrical usurpation. By construing Leicester as a “carped . . . knight” who had “never had merited . . . to be so highly favored of [her Majes]tie,” the earl’s detractors urged “private men” to pass judgment on Elizabeth’s judgment, a necessary preliminary to playing the prince by passing judgment on the sovereign herself.17 In the first play of the Henriad Shakespeare signals his interest in this process by having Bolingbroke preface his usurpation and deposition of Richard II with the execution of two royal favorites who have “misled a prince, a royal king” (3.1.8). Although Richard II does not pursue the implications of this sequence of events, granting little stage time to the king’s favorites, the Bishop of Carlisle’s related question—“What subject can give sentence on his king?” (4.1.121)—haunts the rest of the tetralogy in the form of a fat old man.

The issue of the prince’s fallible judgment, as manifested in the injudicious treatment of favorites, is raised explicitly in 1 Henry IV when Falstaff admonishes Hal, “Do not thou, when thou art king, hang a thief” (1.2.62). This admonition is self-interested; as soon as Hal is crowned, his “fat rogue” of a minion (1.2.187) intends to emulate Leicester in letting “his gredy appetite” range free.18 Even though critics like Kastan equate transgression with resistance to monarchical authority, the fascination exerted by Elizabeth’s eldest minion shows unruliness came in other forms than political dissidence for Tudor subjects. In his eagerness to have “England . . . give him office, honor, might,” Leicester was accused, as Falstaff is, of committing “the oldest sins the newest kind of ways” (2 Henry IV, 4.5.126–29), and committing them “upon her Majesty’s favor and countenance towards him.”19 That Hal appears at first willing to “countenance” the “poor abuses of the time” (1 Henry IV, 1.2.156) in Falstaff thus raises all manner of questions, for, as Falstaff asks of Poins, “if men were to be sav’d by merit, what hole in hell were hot enough for him?” (1.2.107–8).20 By casting these questions in the familiar terms favored by Catholic dissidents, Shakespeare places his “most comparative, rascalliest, sweet young prince” (1.2.80–81) in relation to his own prince, and his “lugg’d bear,” the subject of “the most unsavory similes” (1.2.74, 79), in relation to the queen’s “Bearwhelp,” the subject of “all pleasant discourses at this day throughout the realm.”21

The Falstaff plays allude to the recent past to constitute their audiences as a “remembering public.” By always leaving us wanting “one Play more,” Falstaff is the poster boy for theatrical “ghosting”—the recycling of actors, plots, props, patterns, allusions and so on that, according to Marvin Carlson, encourages audiences “to compare varying versions of the same” material.22 Such “base comparisons” (1 Henry IV, 2.4.250) engage faculties of judgment, and, when they involve historical persons, prompt what Castiglione calls “words of severe censure, of modest praise, and of cutting satire.”23 A Briefe Discoverie objects to Allen’s “offering a comparison betweene the D. Parmaes glorious exploits, and his Lordships [that is, Leicester’s] famous factes . . . as though his vertues were so farre inferiour, to the others” on precisely these grounds. Similarly, when anticourt polemicists likened Leicester to Richard II’s favorites, they were implicitly comparing Elizabeth I to a monarch deposed for showing “too much favor towards wicked persons.”24 Elizabeth’s famous identification with Shakespeare’s Richard II betrayed her well-founded anxiety about the provocative function of such analogic “pastimes,” made particularly dangerous, perhaps, by a theatrical setting. In 1 Henry IV, Henry IV attributes Richard’s downfall to his taste for “shallow jesters” and his consequent vulnerability to “every beardless vain comparative” (3.2.61, 67) before castigating his own son: “For all the world / As thou art to this hour was Richard then” (3.2.93–94). The king’s censure places Hal in the same comparative relation to Richard II as the authors of Leicester’s Commonwealth had placed the queen. As such comparisons show, to go from evaluating the merits of a royal favorite to evaluating the merits of the prince is but a short step—and one abetted by Shakespeare’s introduction of a measure of contrast into comparative relations. The Falstaff plays encourage their audiences to take this step by doing what no dissident pamphlet could do. They provide theatrical substitutes for Elizabeth I, who shine more brightly than she does. The audience is asked to weigh these substitutes’ “glorious exploits” against Elizabeth’s “famous factes,” at least in the matter of countenancing an “old fat man, a tun of man” as chosen “companion” (1 Henry IV, 2.4.448).

The ways in which Falstaff’s multiple transgressions prompt “discourses” is key to these comparative processes. Gossip, slander, and rumor follow Falstaff at the heel, a sure indication of his public notoriety and of his hold on collective memory. In an argument that highlights Falstaff’s connection to the figure of Rumor, Harry Berger Jr. proposes that Falstaff stands for judgment, in that he both represents judgment and asks to be judged.25 Like Berger’s Falstaff, Leicester was a knowing collaborator in his prince’s project, “growne so far” in her “Majesties favor” as to inspire “much talke . . . muttered in [every] corner, [and] much whisperinge.”26 Although commentators disagreed in their assessment of the earl, they agreed that he generated compulsive chatter and found themselves retelling his story in an effort to substantiate their judgments. The attacks of the 1580s had initiated a series of responses and imitations over the next few decades—an unprecedented phenomenon that the theorist Michael Warner might identify as the “concatenation of texts through time” that conjures a public.27 This public was not organized around the ideological values of the exiled Catholics who helped call it into being: several of the texts concerned came out of court circles, show signs of Protestant affiliation (e.g., the anonymous News from Heaven and Hell), or reflect the mixed motivations of theatrical entrepreneurs (e.g., The Henriad and The Merry Wives of Windsor). What the audiences for these works did have in common was a taste for satiric representations of fat, vain, thieving, lecherous, cowardly, lubricious, hypocritical old men: the kind whom “men of all sorts take a pride to gird at,” the ones who are “the cause that wit is in other men” (2 Henry IV, 1.2.6, 10).

By situating Falstaff in the context of anti-Leicestrian discourses, I show that Shakespeare’s old knight is a vehicle not just for thinking about the Elizabethan court, but also for thinking about the public theater’s relation to that court and the society it governed. In making Falstaff, Shakespeare transformed the raw materials of Leicester’s “black legend” through his distinctive modes of theatricality, self-reflection, and showmanship.28 Like his own “honey-tongued Boyet,” Shakespeare is in this “wit’s pedlar,” retailing courtly “wares” while “grac[ing them] with such show” that he outperforms his models (Love’s Labour’s Lost, 5.2.317–34). I mention Boyet not only because Berowne’s description articulates in Shakespeare’s own terms the “populuxe” appeal, subversive impact, competitive motivations, and commercial value of early modern theatricality, but also because Boyet is the resented servant of a convention-defying princess. Love’s Labour’s Lost (1594–95) thus calls attention to a category of analysis—gender—often disregarded in public sphere approaches to Shakespeare’s works but crucial to the evaluation of Elizabethan political phenomena.29 Falstaff is more closely associated in the critical tradition with the transcendent “agency of [Shakespeare’s] theater itself” than any other character, with the possible (and significant) exception of Cleopatra.30 To take seriously Falstaff’s contention that he is Diana’s minion is to accept Elizabeth’s central influence on the transformative powers of Shakespeare’s art. This chapter traces one aspect of that influence, the way that the unconventional and scandalous relationship between the aging queen and her elderly favorite contributed to a Shakespearean theater that sought sport and profit from exposing political material to public evaluation.

Among Falstaff’s salient features in this regard is his unparalleled ability to incite judgment and thereby to induce “other men,” including playgoers, into a community defined by the willingness to engage in critical dialogue: what matters about the old knight is not so much that he is witty in himself but that he is the cause of wit in others.31 The radical impulses that critics identify with Falstaff—his so-called “resistance to the totalizations of power”—inhere in this effect.32 There is something democratizing about a process that unites and elevates “men of all sorts” in the intellectual baiting of a figure associated with Elizabeth I. There is also something gendered at work in this process. The exercise of wit and judgment, faculties that, as Castiglione’s emphasis on them shows, were associated with elite masculinity, compensates for and even averts the threat of erotic and political subjugation that the lecherous old man embodies.33 The age-in-love trope has the potential to catalyze horizontal exchanges as well as vertical ones, since it moves people to discriminate according to age and gender rather than class. Shakespeare seizes on this potential in his unforgettable portrait of “an old fat man” who looks to be made “either earl or duke” (1 Henry IV, 5.4.142) by rendering dubious service to his prince (in the Henriad) or his mistresses (in Merry Wives).

That Shakespeare’s dissolute favorite glances at Elizabeth’s deceased favorite is not as much of a stretch as might at first seem. Leicester died eight years before the first Falstaff play was staged, of “continuall burning Feaver,” or what Mistress Quickly calls “a burning quotidian tertian” (Henry V, 2.1.119).34 But the earl had by then achieved a lasting impact, due to his dual status as the period’s preeminent patron and its favorite target of invective. The form this celebrity took was all the more unprecedented for being diachronic; even postmortem, Leicester continued to represent certain feared, despised, and admired traits in the English imaginary.35 Writing about this long afterlife in seventeenth-century political discourses, Perry shows that “the changing uses of the image of Leicester provide an excellent case study of the longevity”—and, I would add, the commercial viability—“of topical reference.”36 Notably, Shakespeare highlights the issue of Falstaff’s afterlives. All three plays featuring the old knight ask us to compass his death and to imagine him at his final judgment. By recycling the motifs of Leicester’s posthumous reputation, these aspects of Falstaff’s characterization exploit the “perpetual infamy” that Castiglione ascribed to the old man in love, and that Leicester embodied for his contemporaries.37

Leicester’s self-promotion laid the groundwork for his lasting cultural cachet. While his was in some ways a traditional sense of politics, the earl relied on newfangled methods to pursue his ends.38 Like the “popular breeches” described in Jonson’s Cynthia’s Revels (1600), a satiric comedy about court favorites, Leicester was “not content to be generally noted in court” but did “press forth on common stages and brokers’ stalls to the public view of the world.”39 He did so by commissioning frequent and frequently copied portraits of himself, and by accepting the dedications of over a hundred printed books, available for purchase in “broker’s stalls.”40 For Jonson as for Jeff Doty the word “popular” designated “communicative acts that subjected political matters to the scrutiny of ‘the people.”41 Because of the personal nature of Elizabethan politics, the matter that the earl most often sought to communicate about was himself. Jonson attributes to the “common stages” a role in the popularization of court materials, thinking perhaps of the enterprising earl. Leicester had patronized a traveling troupe of players from the moment he took office as Master of the Horse in 1558 to the moment he died in 1588, and helped launch the careers of James Burbage, Will Kempe, John Heminge, and possibly Shakespeare himself.42 These actors, who would go on to found the Lord Chamberlain’s Men, valued the connection with Elizabeth’s eldest favorite enough that in 1572 they requested and were granted the right to become his liveried household retainers.43 The earl spent copiously on clothes for his actors, including livery shirts adorned with the Dudley bear badge and ragged staff, meant to advertise the troupe’s relationship to him. As Ann Rosalind Jones and Peter Stallybras remind us, “memories and social relations were literally embodied” in such garments.44 When others uttered “leawd words . . . ageynst the raggyd staff,” the earl’s players took umbrage because their own identities were at stake.45 As long as audiences remembered Leicester’s men, these players could no more shed their employment history than they could shed their skin.46 Like Jonson’s pants, the actors carried their courtly past onto the “common stages,” inviting the ghost of their old patron to haunt their performances. The theatrical metaphors that became part of the evaluative lore on the earl reflect his long-standing association with players of all kind, including those at the Globe, and conveyed a widespread perception that he was an inherently theatrical person.

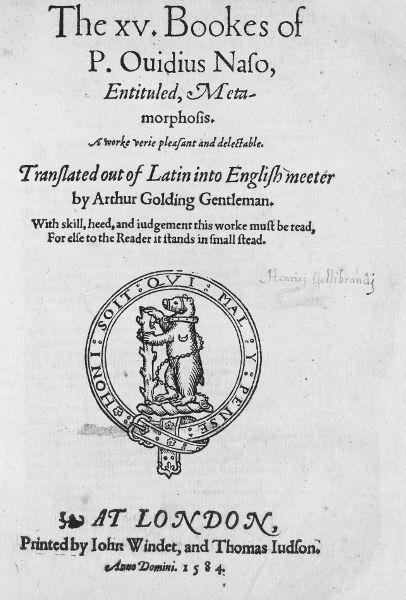

Not content to show himself only on stages, Leicester was also a pioneer when it came to using the new modes of publicity afforded by the printing press. Entertainments like the ones he hosted at Kenilworth helped shape Shakespeare’s imagination not just because they were spectacular, but also because they found their way into print, and so into the stalls of booksellers. As we saw in the last chapter, George Gascoigne’s Princely Pleasures was reissued in the late 1580s, when Shakespeare was in his mid-twenties, so that it continued to “advertise [the earl’s] position as the queen’s favorite” for years after the original performance. Although some scholars speculate that Shakespeare attended the entertainments as a boy, it is more likely that he read about them in works like Gascoigne’s.47 Other books pressing the earl’s case also found their way into the playwright’s hands. Gascoigne’s The Noble Arte of Venerie or Hunting (1575) includes a woodcut of the kneeling earl, offering the choice part of a deer to the queen during a hunting party at Kenilworth.48 Spenser’s The Faerie Queene (1590, 1596) glances at the earl in the character of Arthur, an association that Leicester had promoted at Kenilworth and that might explain the Hostess’s insistence that the dead Falstaff is “not in hell” but “in Arthur’s bosom” (Henry V, 2.3.9–10). Arthur Golding’s translation of Ovid’s Metamorphoses (1576), the source for multiple allusions describing the effects of lust on older Shakespearean males, displays the Dudley bear and ragged staff on its title page, and includes a long dedicatory letter to “the ryght Honorable and . . . singular good Lord, Robert Erle of Leycester.” Most pertinently, perhaps, the major source for Shakespeare’s history plays, Holinshed’s Chronicles (1587), offers up a long description of the earl’s banqueting in the Netherlands, as well as a treatise establishing his aristocratic credentials, including his descent from the Beaufort Earls of Warwick.49 By the mid-1590s, when Shakespeare began writing the Falstaff plays, he had to look no further than his bookshelf for the “famous factes” about the earl.

The malicious gossip about Leicester proved as enduring as his efforts at self-promotion. Through the 1590s, commoners continued to be brought before the authorities for claiming “my lord of Leicester had four children by the queen’s majesty.”50 In 1592, Nashe’s Pierce Penniless’s Supplication to the Devil recalled a time when “the beare . . . being chiefe burgomaster of all the beastes under the lyon, gan thinke with himself how hee might surfet in pleasure.”51 As such references show, where Leicester had pursued popularity, he obtained notoriety; this “pathological version of fame” was an unintended effect of forces that he had sought to harness to his own ends—“emergent capitalism” and “textual and theatrical reproduction.”52 The proliferation of “millions of impieties “sith [the earl’s] death,” abusing “the people by their divelish fictions . . . all to bring” Leicester’s “vertues & person in popular hatred,” prompted an impassioned posthumous defense, “The Dead Mans Right,” in 1593.53 Coy about the precise nature of the multitudinous slanders involved (the anonymous author only notes that these made his ears blush), the tract nevertheless suggests that the materials derived from Leicester’s Commonwealth continued to shape the earl’s public image long after he died.54

Fig. 4. Title page of Arthur Golding’s translation of Ovid’s Metamorphoses (1584). By permission of the Folger Shakespeare Library.

Meant to alarm, Leicester’s Commonwealth had succeeded in entertaining. As Perry points out, plays ranging from The Spanish Tragedy (ca. 1587) to The White Devil (ca. 1612) continued to assume “a ready familiarity” with its slanderous contents.55 While these tragedies allude to Leicester’s reputation as a Machiavellian politician, other works show the late earl as “the noble lecher / that used art to provoke.”56 The recurrent pun on lecher/Leicester confirms that the “nascent public sphere of the Elizabethan era involved identity and decorum more than rationality or policy, and was often irreverent rather than somber.”57 Playing on the bear and ragged staff, the more salacious entries in Leicester’s “black legend” expose the earl explicitly to mocking social judgments. One poem rejoices, for example, that

The stately Bear that at the stake would stand

’Gainst all the mastiffs stout that would come forth

Is muzzled here and ringed with our hand . . .

Great Robin, whom before all could not take,

Is here by shepherd’s curs made for to quake.

Thus may we learn, there is no staff so strong

But may be broken into shivers small

No beast so fierce the cruel beasts among

But age or cunning gins may work his fall.58

The poem reflects conventions established by Leicester’s Commonwealth in relating the earl’s bear badge, his upstart ambition, his bestial nature, and his failing genitals. But it also outdoes its source by envisaging the “staff so strong” reduced to “shivers small” by “shepherd’s curs.” Emphasizing the class differential between the bear and his pursuers, the poem endows these curs with the homegrown courage of the celebrated English mastiff.59 The “fall” of the earl’s “staff,” meanwhile, stands for the moralistic and socially conservative admonition “to be content and not desire / For all do fall that do aspire.”60 In this way, the earl’s impotence becomes the inevitable consequence of his social mobility and sexual opportunism. Shakespeare mines this same vein of humor in his representation of Falstaff.

Nowhere are the salient aspects of Leicester’s posthumous reputation more entertainingly on display than in News from Heaven and Hell, an unpublished satire written by an anonymous adherent of the court sometime after the earl’s death in 1588. In its competitive escalation of inherited materials, the little-known News sets a precedent for Shakespeare’s conversion of Leicester’s black legend to theatrical purpose. Among other things, this satire makes elaborate and equal opportunity fun of both the earl’s “ragged” and his “Stewardes staff.”61 The anonymous author evokes a theatricalized world, in which Heaven is a kind of castle, as in the morality tradition, and hell the domain of vice-like fiends. News’s “quandam Earle of Lescester” is a lover of the moon, who shares multiple traits with Endymion’s Sir Tophas, including a rotund physique, a fondness for having “a page” carry a “bole of wine to refresh him,” and a tendency to lecherous and animalistic behavior (144, 146). By devising condign punishments for this elderly lover, News shows the figure of Leicester-in-lust remained attractive to writers because it authorized their political judgments. The satire thus corroborates the suspicions of pro-government thinkers that the “slanderous inveighing” against the queen’s great favorite contributed to a usurpation of royal prerogative, which might result in “private subjects” allocating to themselves “the power of setting up and putting downe Princes.”62 That such power is a source of great pleasure is implied by the frankly pornographic bent of the narrative.

News signals its participation in a broader and ongoing discussion about the earl by its self-conscious orientation toward a remembering public familiar with anti-Leicestrian lore and eager to hear “the last reporte . . . brought by the post” of the earl’s adventures (158). Although it never saw print, News thus shows the reflexivity and attention to temporality that Warner defines as characteristic of public-making texts.63 In addition to engaging in the “traffic in news” about the earl, News invites debate by construing its readers as members of a jury, instructing them to “waye” with their “charytable wisdomes” what the earl deserves (155), and elevating them to the level of St. Peter and Pluto, the authorities passing judgment within the narrative.64 Its legalistic account of the earl’s postmortem travails capitalizes on the notion first aired in Leicester’s Commonwealth that Leicester has “a conscience loaden with the guilt of many crimes, wherof he would be loth to be called to accompt or be subject to any man that might by authority take review of his life and actions when it should please him.”65 The author introduces Leicester’s ghost on his way to Final Judgment, clad in “a fine white shirte wrought with the beare and the ragged staffe,” with “his Stewards staffe of office in his hande,” trying “with shewes to delude the worlde there as he had done here” (144). Where in life the earl’s “vaine pompe” (144) fooled the powers-that-be, including Elizabeth I, in his imagined afterlife “Munsur Fatpanche” (146) meets with a more discerning public, alerted to the pleasures that await by the coy references to the bear badge. News recycles old material for its “corpulent” (145), lubricious, and theatrical antihero but also adds new touches, endowing the ghost with such a propensity for “much sweating,” that his embossed “shirte” becomes “all wet” (145–46), a nod to the mysterious fever that killed Leicester, and to the fiery torments that await him.

In its depiction of these torments, News reconfigures the familiar device of bearbaiting to draw attention to Leicester’s violations of gender and generational norms. The author’s tongue-in-cheek construction of heaven as situated near the “orb of the moone” equates Leicester’s failure to enter the pearly gates with his misguided attempts to enter the “bewtifull venirus dames” who had “dazeled him on earth” (146). Escorted by Sarcotheos, the god of flesh whom he worshipped in life, “Munsur Fatpanche” finds himself put on “triall” by St. Peter for his lechery and his “wantonnes of flesh” (148–49). Where the portly ghost repents other sins—the author offers a lengthy list of these, including various murders and “the robbing and stearving of pore souldiers” in the Netherlands (152)—he confesses that he holds lechery “no sinne”: “it was so swete and I accustomed to it even from my youth” that he “could never repent me of it nether in youth nor age” (154). After clarifying that he disdains the conventional distinction between youthful “lustynes” and the “gravitye” proper to old age, the ghost volunteers for castration to avoid damnation. He begs “to have the member only punnished that hath only offended” (154).66 Instead, St. Peter has this “bellye claper marked with an L”; far from signifying that “he had bene a great lorde,” it brands Leicester a lecher (154). The pun on Leicester’s name designates the earl’s conversion of sexual service into political capital as his supreme offence.

Chained by his branded member to an “iron brake,” his “privites” made to “enduere” such abuse that he made a “dolfull sight for any his beawtifull ladies . . . to have beheld,” his “Robinships” is then carried off to hell, where

a naked feind in the forme of a lady with the supported nose should bend this bere whelp in an iron cheane by the middle and . . . she should be so directly placed against him that the gate of hir porticke conjuntcion should be full oposit to the gase of his retoricke speculation, so that he could not chose but have a perfit aspect of the full pointe of her bettelbroude urchin in the triumphant pride and gaping glory thereof. Now there was no doubte made but that this pleasant sight, togeather with the remembrance of his wounted delight, would make his teath so to water and geve him such an edge that he could not forbeare . . . to geve a charge with his lance of lust against the center of her target of proffe, and rune his ingredience up to the hard hiltes into the unserchable botome of her gaping gullfe. . . . Thus was his paradice turned into his purgatory, his fine furred gape into a flaminge trape, his place of pleasure into a gulfe of vengeance, and his pricke of desire into a pillor of fier. (155–58)

This scene of pornographic bearbaiting translates into infernal terms Castiglione’s contention that those who give in to “unbridled desire” soon return to it, experiencing once more “that furious and burning thirst.”67 Where most early modern scenarios of sexual abandon focus on the transgressions of the female partner (e.g., Spenser’s Acrasia), this one highlights the male’s culpability. With his head below the fiend’s “bettelbroude urchin,” the ghost reenacts his violation of normative heterosexual relations in which the man functioned as the head to the woman’s body.

By depending on familiarity with preexisting materials for its humor, News illustrates the ways in which satire “near and familiarly allied to the time” draws on its readers’ memories to constitute them as an “adjudicating public.”68 The ghost’s “pricke of desire,” for example, glances back at the Kenilworth entertainments, where Leicester had presented himself as the holly bush Deep Desire, animated by “the restlesse prickes of his privie thoughts.”69 That this same “pricke” is now turned to a “pillor of fier” frames the earl’s courtship of the queen as a cause of damnation. Although the identity of the “lady with the supported nose” is ambiguous, paradoxical references to her demonic double’s “gaping g[u]llfe” and “bottomeless barrell of virginnitye” evoke the woman who was ever the “center” of Leicester’s ambitious and amorous designs; who had costarred in the bearbaiting in Leicester’s Commonwealth (see chapter 1); and who had endured controversy about her own “gaping gulf” (157).70 Multiple allusions to the Dudley badge further establish the earl’s bestial nature, while singling out his phallus—described in prosthetic terms, as a pillar, lance, or staff—for condign forms of punishment. The discursive detachment of the earl’s penis from his body proper culminates in his fiery castration, an emasculation reinforced by the ghost’s narrative status as the feminized object of the readers’ gaze and the satiric butt of the readers’ laughter. By provoking derisive laughter, the author positions his readers as knowing and authoritative collaborators in the castigation of the deceased earl. News from Heaven and Hell offers a compensatory fantasy of empowerment, in which the sexual and generational inversions of the Elizabethan court are avenged through the immolation of this old lecher/Leicester, forced “to offer dayly to his god Priapus . . . a burnd sacrifice,” and reduced in the process to a mere “feminine suppository” (157).

As News shows, Leicester’s death, far from quieting his critics, reenergized them. Elizabeth’s councillors were right to think that far more was at stake (so to speak) in “the slanderous devices against the said Earl” than the personal animosity and angry grumblings of a Catholic minority.71 A. N. McLaren argues that Elizabeth I’s gender helped men like Leicester arrogate unprecedented power. It also made them vulnerable to the chastening attacks of inferiors. The perceived sexual subjection of the queen’s aging favorites authorized other subjects to speak against and about them by virtue of their own conformity to gender and generational norms, a process that contributed to the emergence of a public sphere during this period. Leicester’s “legend” belongs to the “gossip about public figures” better described as scandal, in that it circulates among strangers and “has both reflexivity . . . and timeliness.”72 Knowing references to the earl as a man whose “experience in chamberwoorck exceeded his practize in warr” survived him for many years.73 The longevity of Leicester’s “black legend”—the paradox of its enduring timeliness—indicates that it addressed a range of concerns about early modern government, as Perry shows. The age-in-love trope contributed to this phenomenon by drawing the unseemly body of the queen’s “amorous minion” into public discourse for the purposes of ridicule, a process that encouraged subjects to think themselves more discerning than their queen, and that established the authority of communally held social norms over that of the monarchy. Such factors explain why as late as 1593 the author of “The Dead Mans Right” accused the “ungratefull Malecontents” who spread “rebellious and seditious Libells” about the dead earl of having “an aspiring minde,” and felt an obligation to defend the queen, who had “wisely judged of [Leicester’s] vertues, and worthily rewarded his loialtie and paines.”74 Notably, the last installment of the Elizabethan tradition, Leicester’s Ghost (ca. 1602–04, printed in 1641), reproduces the usual charges about the lascivious earl, who used “strange drinks and Oyntments . . . [to make] dead flesh to rise” when he “waxed old.”75 Loath to let such fat meat go, writers imagined the elderly Leicester/lecher postmortem, like so much dead flesh irrepressibly rising from the beyond.

Polemical works on Leicester show how a masculine, disembodied ideal of public life emerges in response to the embodied and sexualized modes of publicity at the Elizabethan court.76 Although the buffoonish figure of Leicester-in-lust first appeared in works opposed to the Elizabethan government on ideological grounds, it proved portable and entertaining enough to cross the divisions that separated the Catholic authors of Leicester’s Commonwealth in Paris from the Protestant author of News at court (News makes scoffing references to the Pope and papists that establish its Protestant bona fides). The cultural mobility of this figure indicates that, rather than conveying narrowly partisan positions, the age-in-love trope had a catalytic effect, encouraging those who encountered it to form and voice opinions of their own. In describing an old ghost damned in hell for being lecherous, News emphasizes the politic pleasures attendant on debating Leicester’s transgressions. Pluto gathers a “solemn assembly,” whose members model deliberative processes by discussing the earl’s punishment: “sum were of opinion that his harte should be pressed through,” while “sum that his hands and fete should be loked in a paier of stokes and manackels which should be made all fiery, of purpose becase his handes had bene always geven to rapine,” and still others that hot sulfur be poured down his throat, that “gaping gulfe of all gluttony, drunkenness, and riott” (156). Leicester’s Ghost also references such a divergence of opinion by noting objections to its narrator’s claims; in familiar terms, he denounces those “Doggs that at the Moone doe fondly barke.”77 Joining the conversation initiated by Leicester’s Commonwealth, these later tracts imagine themselves as contributing to an ongoing and highly entertaining debate about the controversial earl (one that allows, moreover, for surreptitious glancing at other royal favorites). The “slanderous devices” aimed at Leicester by the polemicists of the 1580s had conjured a public eager to consume satiric representations of their government, a public whose members enjoyed discussing and passing judgment on the sexual misbehavior of their superiors. This phenomenon was bound not just to erode the authority of the ruling class but also to attract the notice of playwrights like Shakespeare, “whose main business,” according to Paul Yachnin, consisted of “marketing popular versions of elite cultural goods to public audiences.”78

The association of the surfeiting old man in love and the Elizabethan court was fostered on the common stages by the publication, in 1591, of Lyly’s Endymion, which advertised on its title page that it had been performed “before the Queen’s Majesty at Greenwich,” and which is an acknowledged source for Shakespeare’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream (1595–96), as well as for the Falstaff plays.79 Bottom, Falstaff, Malvolio, Orsino, Claudius, and Antony all follow Endymion in lusting after female characters modeled on Elizabeth I.80 And several of these characters follow Sir Tophas in being hybrids of the miles gloriosus and the amans senex, who violate gender and generational boundaries.81 Where Lyly offers distinct idealized and satiric representations of Elizabeth’s favorites, Shakespeare often confounds the two modes, presenting us with characters who defy easy categorization and who challenge our faculties of judgment. In privileging problems of sovereignty and judgment, Shakespeare’s experiments with aging male characters engage the later tradition on Leicester, and come to altogether different conclusions about the theatrical possibilities inherent in the figure of the lusty old man than his theatrical predecessor did. If, as I argue above, age-in-love tropes function as vehicles for the political empowerment of “aspiring minde[s],” they also provide aspiring playwrights with a means for artistic self-assertion. Indeed, Shakespeare’s repurposing of this inherited material is deeply competitive—he embraces the escalation inherent in anti-Leicestrian discourse by outperforming his models.

An early version of this tendency to confound, recycle, synthesize, escalate, and aestheticize is discernible in A Midsummer Night’s Dream, where Bottom’s amorous encounter with a fairy queen make him into something more than “an ass” (3.1.120). Leonard Barkan argues that the precedent for the meeting between Bottom and Titania is “the story of dangerous eye contact between Diana and Actaeon,” a myth that, as we saw in the previous chapter, came preloaded with courtly associations.82 Like the Leicester of antigovernmental lore, and like Lyly’s Tophas, Bottom deceives himself into thinking that all parts suit him, including that of the lover. The object of his amorous attentions is an infantilizing fairy queen who charms her lover to sleep on a flowery bank: a combination of Spenser’s Gloriana and Lyly’s Cynthia, who shares a name and a taste for “lion, bear, or wolf, or bull” (2.1.180) with Ovid’s Circe.83 In his depiction of this mercurial queen bestowing “sweet favors” on a “hateful fool” (4.1.49), Shakespeare alludes to Elizabeth’s alleged preference for theatrical upstarts and her tendency to emasculate her courtiers. The incongruous “meddling monkey” on which Titania might dote (2.1.181) even recalls one of the queen’s more controversial pet names. Although Ovid’s Circe has no simian creatures dancing attendance on her, Elizabeth had dubbed Jean de Simier, the go-between in her last courtship with the Duc d’Alençon, her monkey. The “sweet favors” she showed that meddling gentleman had enraged a jealous Leicester, causing tongues to wag throughout the country.84

Like Diana and Circe, the Fairy Queen appears in works connected with Leicester’s courtship of Elizabeth, including the Kenilworth entertainments and the Woodstock entertainments (1575, published in 1585).85 Because of such factors Stephen Greenblatt endorses the critical tradition that casts the entertainment at Kenilworth as the inspiration for A Midsummer Night’s Dream, which he characterizes as a “gorgeous compliment to Elizabeth.” If Shakespeare’s play attends to “the charismatic power of royalty,” however, it also manifests an abiding interest in those touched, translated, or “transported” (4.2.4) by that power.86 The phallic image of “Cupid’s fiery shaft, / Quench’d in the chaste beams of the wat’ry moon” (2.1.161–62) pays a Lylean compliment to Elizabeth, praising her ability to raise and to stay male desire.87 But it also reformulates in high poetic terms the lurid image of Leicester’s “pillor of fier” vainly drowning itself in the “gaping g[u]llfe” and “bottomeless barrell of” female “virginnitye.” And, more intriguingly still, in its attention to the swerve of Cupid’s “bolt,” which falls on the “little western flower, / Before milk-white, now purple with love’s wound” (2.1.166–67), it locates the origins of Oberon’s transformative magic in erotic energies misdirected at the Virgin Queen. As we have seen, Leicester was associated with “ointment[s]” meant to “provocke . . . filthy luxury,” similar in kind if not in effect to the “juice” that Oberon uses to make “man or woman madly dote / Upon the next live creature that it sees” (2.1.170–71).88 A Midsummer Night’s Dream, by replaying such familiar motifs in a higher register, renders ambiguous homage to Leicester, relating his role as the queen’s failed lover to his role as the patron who commissioned Golding’s translations of Ovid, the poet renowned for confounding misplaced erotic desire and the “desire with externall fame above the starres to mount.”89

The unorthodox suggestion that the rechanneling of vain desires for the queen enabled a flowering of magical or creative powers—that brutish sleep might lead to a substantial dream—is confirmed by Bottom’s experiences in the play. An ass who falls asleep on stage as Lyly’s Tophas does, and who dreams up an erotic encounter with a fairy queen as Spenser’s Arthur or Chaucer’s Thopas do, Bottom also expresses desires and ambitions that Shakespeare shared. By revising the Actaeon myth to have Bottom’s physical transformation precede his visionary experience, Shakespeare fuses “metamorphic exaltation and degradation into a single, causally connected act.”90 The transformation becomes the enabling condition of Bottom’s “rare vision” of the Fairy Queen, which inspires him “to write a ballet of this dream” entitled “‘Bottom’s Dream,’ because it hath no bottom” (4.1.214–16). A Midsummer Night’s Dream thus parallels Bottom’s experiences with the playwright’s own, encouraging us to find artistic value in the amorous ambitions that the Fairy Queen inspires. Bottom’s encounter with bottomlessness produces radically different results than Munsur Fatpanche’s; to “have been the lover of the Fairy Queen” in this play, Helen Hackett explains, is to have had “a metaphysical experience, a transformatory revelation.”91 Bottom is not, or not only, a satiric butt, since the behaviors that he renders ridiculous are rewarded with improved status by play’s end, when he becomes a “made” man (4.2.18).92 Richard Dutton finds in A Midsummer Night’s Dream “a perfect allegory of relations between the acting companies and the court” at century’s end.93 In Bottom this allegory conflates the role of the actor-playwright with that of the royal favorite. Bottom may become “the privileged vessel” of aesthetic “experience,” but only because he willingly subjects himself to the degraded and degrading desires of a queen.94

Not coincidentally, Bottom is the play’s most memorable character. Shakespeare himself remembers Bottom throughout his career, and endows the characters that derive from Bottom with the same haunting quality, the result of their preposterous violations of social expectations on the one hand and their status as reconstructions of preexisting materials on the other. These two functions are related; according to Patricia Parker, the “Shakespearean preposterous,” a category in which she includes both Bottom and Falstaff, is a means of “breaching” the topic of “responsibility for actions in the past or what had gone before.”95 A Midsummer Night’s Dream concerns itself with conflicted reactions generated by the queen’s leading favorites, the hateful fools who had risen to preeminence by preposterously humbling themselves to please court ladies. Having, in the popular imagination, traded sexual services for high political status, these men were as much a contradiction to the Elizabethan “sex/gender system” as the queen herself.96 A Midsummer Night’s Dream emphasizes the role that individual perception plays in the evaluation of such protean creatures; as Barkan puts it, “that the Fairy Queen sees Bottom as the incarnation of beauty transforms him upward just as surely as the physical change imposed by Puck transforms him downward.”97 Although many, like Francis Bacon, recoiled from “men of this kind,” Shakespeare found that the strange mixture of praise, condemnation, and mockery they elicited made for theatrically compelling material.98

That Shakespeare found much to say on behalf of the men made, or remade, by his queen is best evidenced by his “corpulent” and narcoleptic knight, Falstaff (1 Henry IV, 2.4.422), to whom we are now ready to return. Fat, sweaty, cowardly, drunken, lecherous, hypocritical, and eager to exploit his status as a royal favorite to social advantage, Shakespeare’s “reverent Vice, that grey Iniquity . . . [and] vanity in years” (1 Henry IV, 2.4.453–54) is constituted of the same materials as the Leicester of opposition literature, that greedy figure of “intolerable licentiousness” who became “old in iniquitie.”99 A lying “round man,” who disregards the safety of the soldiers under his command, and who urges his prince to become “for recreation sake . . . a false thief” (2.4.140, 1.2.155–56), Falstaff has been given short shrift by recent literary critics interested in stage representations of royal favoritism, presumably because Hal terminates the relationship when he ascends the throne.100 For the length of two plays, however, Falstaff’s fantasies of social elevation by means of his prince’s ill-judged favor are given free play: “the laws of England are at my commandment,” he gloats when Hal is crowned, “Blessed are they that have been my friends, and woe to my Lord Chief Justice!” (2 Henry IV, 5.3.136–38). When Hal at last turns his countenance from “that vain man” (2 Henry IV, 5.5.44), Hal’s own past is not the only “foil” that sets off his “reformation” (1 Henry IV, 1.2.213–15). Shakespeare’s prince accomplishes a task at which Shakespeare’s queen had signally failed.

The possibility that Shakespeare’s surfeiting “town bull” (2 Henry IV, 2.2.158) glances at the “common bull of the court” need not preclude other well-established “pastimes,” including the identification of Falstaff with Lord Cobham, or his connection to the Marprelate controversy.101 On the contrary, the layering of possibilities contributes to the celebrated richness of Falstaff’s character. A quintessentially theatrical creature, Falstaff never fails to generate “the uncanny but inescapable impression . . . that ‘we are seeing what we saw before.’”102 Throughout the Falstaff plays, Shakespeare urges audiences to recognize that they are revisiting familiar ground. Falstaff famously refers to the recent kerfuffle over his original name (offensive to Cobham because Oldcastle was an ancestor by marriage), for example, when he assures us that Oldcastle is “not the man” (2 Henry IV, epilogue, 32), in effect publicizing the Cobham reading while quashing it.103 He also encourages further speculation regarding the intended target: if Oldcastle is not the man, who is? Meanwhile, the new name signals a renewed emphasis, in the wake of the Cobham affair, on the conjunction in Falstaff of the amorous minion and the “aged counselor.”104 Where “Oldcastle” evokes an elderly courtier (as in the phantom reference to “my old lad of the castle” [1 Henry IV, 1.2.41–42]), “Falstaff,” with its familiar pun on detumescence, highlights that character’s sexuality, the subject of knowing jokes in the plays that feature him.105

The characterization of Falstaff as a hypocritical Protestant is consistent with both the Cobham controversy and the materials of Leicester’s black legend. In A Briefe Discoverie’s view, the “infamous libels” about the earl “secretly cast out and spred abroad” were motivated by the fact that he was “one of the greatest, & principall patrons of true religion.”106 Perhaps, then, Shakespeare turned to Oldcastle, the proto-Protestant leader accused of treason, because of his commonalities with Leicester, another Protestant leader accused of treason.107 Consider the woodcut in Foxe’s Actes and Monuments, which shows Oldcastle chained to the gallows, yet another sweaty old man subjected to fiery baiting.108 The “image of the grotesque puritan” that Falstaff evokes, while popularized by the Marprelate controversy, first gained currency when Leicester was depicted as an “icon of bacchanalian revelry,” given to “overmuch attending his pleasures” and excessive “drinking and belly chere,” nearly a decade before Shakespeare’s fat knight disgraced the English stage.109 A “roasted Manningtree ox” (1 Henry IV, 2.4.452), a “whoreson little tidy Bartholomew boar-pig,” who needs to leave “foining a’ nights” and “patch up” his “old body for heaven” (2 Henry IV, 2.4.231–33), Falstaff appears destined to suffer a familiar fate for his defiance of age and nature. When he recoils from “remember[ing]” this promised “end” (2 Henry IV, 2.4.235), his odd locution suggests a kind of textual déjà vu, as if the self-conscious fat man remembers always already being dismembered.

Over the course of the three plays in which he appears, the entire “dictionary of slanders” devised for Leicester is leveled at Falstaff.110 The correspondences between “Munsur Fatpanche” in News and Shakespeare’s “fat paunch” (1 Henry IV, 2.4.144) are numerous: both sweat copiously enough to stain their shirts (2 Henry IV, 1.2.208–10, 5.5.24–25; News, 146); both are “greasy” (1 Henry IV, 2.4.228; News, 148); both are likened to a “Flemish drunkard” (Merry Wives of Windsor, 2.1.23; News, 148); and both stand accused of “gluttony, drunkenness, and riot,” as well as lust. Although we never see Falstaff in hell, we are repeatedly asked to imagine him there, by Hal’s references to him as a “devil” or an “old white-bearded Sathan” (1 Henry IV, 2.4.447, 463), or by his own wistful musings that “If to be old and merry be a sin, then many an old host that I know is damn’d” (1 Henry IV, 2.4.471–72).111 Even Falstaff’s telltale name evokes anti-Leicestrian discourses: not only does News make jokes about the ubiquitous bear and ragged staff, it also imagines Leicester’s ghost letting “fall [his] staffe” of office for fear of being sent to hell (150). The falling staff was a favorite symbol for what we would now call Leicester’s erectile dysfunction—a tactic that Shakespeare exploits in his depiction of his “wither’d elder,” whose “naked weapons” form the constant object of his own as well as other men’s wit. “Is it not strange,” Poins asks Hal as they observe the old man flirting “that desire should so many years outlive performance?” (2 Henry IV, 2.4.258, 207, 260–61).112

At the theater, such verbal resonances were substantiated, quite literally, by the actor who likely personated Falstaff: the clown Will Kempe, who had been a member of Leicester’s troupe, and whom Sir Philip Sidney referred to familiarly as “my Lord of Lester jesting plaier.”113 Kempe’s Bottom must have shaped the reception of Kempe’s Falstaff, prompting returning spectators to compare Falstaff’s relationship with Hal (or with the merry wives) to Bottom’s relationship with Titania.114 Shakespeare exploits Kempe’s past in other ways, too. Hal draws attention to the clown’s former employment when he notes “how ill white hairs becomes a fool and jester” (2 Henry IV, 5.5.48). Kempe had been with Leicester at his court in the Netherlands (according to News and other sources, a carnivalesque place of “quaffing” [148], more like a tavern than a place of business), where the earl used the clown to entertain local magnates fond of drinking, gaming, and rioting.115 Spoken by this former servant, the remark about knowing an old host (or an old ghost, in the alternate reading of this line) damned for being merry thus takes on a topical cast. References of this sort served as “the animating spark” of early modern clowning, and, according to Robert Hornback, Kempe had developed a special knack for satirizing the puritans associated with his former employer.116

Even the garments Kempe wore may have evoked his deceased patron for members of the original audience. A conversation between Falstaff and Pistol in the crucial moments before Hal’s rejection calls repeated attention to what Falstaff’s clothing “doth infer” or “show” (1 Henry IV, 5.5.13–14). As Jonson’s “popular breeches” show, old clothing repurposed as theatrical costume carried its history on to the stage, where it could materialize relations with court figures, thus exposing these to the audience’s collective judgment. Such old clothes inferred a “world of social relations,” carrying with them memories which had the power to “mold and shape” the wearers “both physically and socially.”117 Actors were alert to these powers and used them to produce certain effects. Henry Wotton felt that Globe actors who showed like “Knights of the Order with their Georges and garters,” for example, made “greatness very familiar, if not ridiculous.”118 When Falstaff dreams about having “new liveries” made (5.5.11) as he stands “stained with travel, and sweating with desire to see [Hal], thinking of nothing else, putting all affairs else in oblivion, as if there were nothing else to be done but to see him” (5.5.24–27), we are made to take special note of his costume.119 Alluding to Elizabeth’s motto—“’Tis ‘semper idem’” (5.5.28)—Pistol frames the tableau of the devoted old knight in his sweaty shirt as a reenactment of previous events, a staged memory. Did Kempe don his old livery garments, adorned with the Dudley bear and ragged staff, to play Shakespeare’s fat favorite?120 And did the clown in staging the dream “of such a kind of man, / So surfeit-swell’d, so old, and so profane” (2 Henry IV, 5.5.49–50) put on the manners of his ex-patron, a man infamous for embodying these traits, notorious for his breach of generational decorum, known to have been killed, as Falstaff fears that he will be, both with “hard opinions” and “a sweat” (2 Henry IV, epilogue 30–31)? Whatever the answer to these questions, we might see in Leicester’s jester playing Falstaff the embodiment of the theater’s commodification of court materials.

Leicester was a natural candidate for such treatment, not only because of his notoriety, but also because of his deep associations with the theater in general and fools in particular. According to his critics, the earl was a man “full of colors, juglinges, and dissimulations” who had earned the queen’s favor through his talent for “shewes” (News, 156, 144), and who therefore had an affinity for “harlotry players” (1 Henry IV, 2.4.395–96).121 These constructions of the earl as a man of the theater had, as we have seen, a basis in fact. Leicester had presided over key events in the development of the theater as an institution, including the grant of the first royal license in 1574. In this document, the queen awarded special privileges to Leicester’s troupe in exchange for “the recreation of oure loving subiectes [and] for our solace and pleasure.”122 The man accused of elevating himself by serving the queen’s “filthy lust” thus procured the social elevation of actors, so that they could serve the queen’s “pleasure.”123 Leicester also furnished Elizabeth with her official fool, Richard Tarleton, who served the queen’s pleasure so efficiently that he became Groom of the Chamber and Master of the Fence.124 The licensed fool and the licentious favorite occupied similar positions in relation to the queen: both agreed to humiliate themselves to elevate themselves. The homology between earl and actor, favorite and fool, struck observers, like the author of News, who makes “Tarlton his ruffin” a member of the earl’s seedy entourage in hell (155). Critics have long linked elements of Falstaff’s characterization to the foolery of Tarleton and Kempe.125 Falstaff’s taste for histrionics and his talent for self-promotion—he hopes to translate his talent for counterfeiting into an earldom or a dukedom and to immortalize himself in printed ballads with his “own picture on the top” (2 Henry IV, 4.3.48–49)—reflect their enterprising former patron as well. Collapsing the distinction between fool and favorite, Shakespeare gives us in Falstaff a “ruffin” (2 Henry IV, 4.5.124) who is both Leicester and jester, a royal minion confident of his ability to please “the gentlewomen” but understandably more anxious about his reception with men (2 Henry IV, epilogue, 23–24).126

The network of connections tying Leicester to the theater must have registered differently with Shakespeare and his colleagues than with the authors of opposition tracts, a factor that helps account for the ambivalence and ambiguity in the character of Falstaff. When polemical writers made a taste for histrionics a component of the earl’s notorious identity, they meant no praise to the earl or to the theater: in their hands, “age in love” is an antitheatrical trope, which conflates dramatic performance with categorical transgression, attributing both to the queen’s Circean powers. If the incident with William Storage offers any indication, in 1588 members of the earl’s troupe viewed attacks on his “raggyd staffe” as attacks on themselves: they identified their professional fortunes with his reputation, which they defended.127 Nearly a decade later, with Leicester dead and that reputation destroyed, and with the theater staking out a new and more independent position for itself, matters had gotten more complicated. Whatever Shakespeare and Kempe were up to with their “Sir John Paunch” (1 Henry IV, 2.2.66), they were not in the business of defending or attacking the historical Earl of Leicester. Like Joseph Roach’s Betterton, the multiply-ghosted figure of Leicester’s jester playing Falstaff may have functioned instead as a kind of “effigy” to “gather in the memory of audiences.”128 Leicester’s notoriety showed “perpetual infamy” to be a hot commodity; “loud Rumor,” a “pipe / Blown by surmises, jealousies, conjectures” upon whose “tongues continual slanders ride” (2 Henry IV, prologue, 2–16), seems always to leave people wanting more. Strikingly, Shakespeare’s unholy goddess figures slander as a kind of political “news,” brought by “the wind, [her] post-horse,” to an eager public which spreads “from the orient to the drooping west” (2 Henry IV, prologue, 38, 3–4). The metaphor of the wind, which, as we saw in the last chapter, was used by Lyly and Sidney to describe verbal assaults on Leicester, conveys the boundlessness associated with the circulation of slanderous materials among potentially infinite strangers. Thanks to the invocation of Rumor, for the duration of 2 Henry IV, the audience in Shakespeare’s theater is made coterminous with this virtual public of “open . . . ears,” eager to be stuffed with “false reports” (prologue, 1, 8). All become avid consumers of Rumor’s news, who taste of the “contempt” that she inspires and assume the feelings of “moral superiority” that she retails.129

Although the queen’s councillors worried about notoriety and wise individuals tried to avoid it, Shakespeare harvested its perpetuating and leveling energies to theatrical ends.130 He is predictably self-conscious about this development. When Poins and Hal secretly observe, laugh at, and pass judgment on the “strange” disjunction between Falstaff’s age and his sexual desires, the metatheatrical device highlights a shared, voyeuristic fascination with the clownish spectacle of senescent male sexuality. This self-reflective moment illustrates the process by which a violation of sexual and generational norms transforms individual spectators into a critical public, defined and elevated by its collective adherence to rules of social and moral decorum. According to Hobbes, laughter on such occasions results from “the sudden glory arising from some sudden conception of some eminency in ourselves, by comparison with the infirmity of others.” Earlier thinkers, too, had commented on the emancipatory force of communal laughter; in a passage decrying the tendency of plays to extend “judgement” to “the worste sorte,” Stephen Gosson rebukes defamatory depictions of real people that provoke the “wonderfull laughter” of the “commen people.”131 Even Falstaff comments on the socially productive force of laughter, which he relies on to secure his position with Hal: “I will devise matter enough of this Shallow to keep Prince Harry in continual laughter” (2 Henry IV, 5.1.78–80). 2 Henry IV dramatizes the power of the theater to unite and elevate its audience through “continual laughter.” Made privy to the conversation between Hal and Poins, the audience is invited to pass judgment by laughing with the prince. The common work of enforcing social norms through laughter suspends class divisions, so that Shakespeare’s audience momentarily participates by means of theatrical proxy in the “being of the sovereign.”132

As Poins’s offer to “beat” Falstaff “before his whore” (2 Henry IV, 2.4.257) suggests, the figure of the old man in love also instills a desire for more spectacles, of a distinctly punitive kind. There was a vogue for such spectacles at the turn of the sixteenth century: Merry Wives, Twelfth Night (1601–2), Hamlet (1600–1601), The Revenger’s Tragedy (1607), and Antony and Cleopatra (1608) are all extended exercises in beating old men before their whores. By dwelling on the sexual subjection of their elders, and reducing these bloat men to “huge hill[s] of flesh” (1 Henry IV, 2.4.243), Hal, Poins, Hamlet, Octavius, and Vindice claim the masculine authority associated with disembodiment for themselves. Barbara Freedman wonders why “Shakespeare was interested . . . in writing about clownish male sexual humiliation and punishment.”133 One answer is that this theatrical pattern appealed to disenfranchised, second-generation Elizabethan men, weary of (or eager to reflect on) their double subjection to the queen and her aging minions. Like Poins, who remembers with pleasure “how the fat rogue roar’d” when Hal describes Falstaff “sweat[ing] to death” (1 Henry IV, 2.2.108–9), or the writer of News, who fantasizes “Munsur Fatpanche” subject to eternal fiery torment, these younger men must have enjoyed watching their elders burnt in effigy.

While Hal’s “I know thee not, old man” (2 Henry IV, 5.5.47) may mark a collective reaction to the Elizabethan regime, it had more intimate implications for Shakespeare and his colleagues. The age-in-love trope helped them not just to capitalize on but also to distance themselves from their own institutional past, tainted by the very condition that glamorized it: service to the moon’s pleasure. In this context, Falstaff’s desire for new livery signals a shift in institutional allegiance from the patronage system to the public theater. His old shirt, soon to be discarded, becomes a reminder of the duty, obedience, and service owed the infamous earl. The parricidal themes that attend Hal’s rejection of Falstaff suggest Shakespeare’s adulterating awareness of the treachery involved in this process. The Falstaff plays coincide with a period of transition in the history of the theater, which culminated with the 1598 edict “allowing” only the Lord Chamberlain and the Lord Admiral’s men, a “watershed” event that Richard Dutton argues changed the status of shareholders in these companies, lifting them from a vagabond state to a “privileged position.”134 Before they secured this position, the artisans of the newly professionalized theater had occasion to reflect on their ambiguous status in relation to the court. Although their former patron had become a target of widespread satire, he may have also functioned as an aspirational model for these theatrical artists, who, like Falstaff and Bottom, sought to translate their histrionic talents into social and material advantage. Kempe playing Falstaff is, among other things, a servant parodying his deceased master to secure the patronage of a new one, the paying audiences of the public stage: at once an image of a kind of petty treason, an eloquent and multifaceted figure of love and betrayal, and a poignant reminder of how close the “harlotry players” had once been to the celebrated queen.

In his final moment in the histories, Falstaff conveys the ambiguity of his position by kneeling, “before you”—that is, the mixed audiences of the theater—“but indeed, to pray for the Queen” (2 Henry IV, epilogue, 16–17). In this posture Falstaff recalls iconic representations of courtly submission, like the Leicester pictured in Gascoigne’s Noble Arte, or the epilogue of Endymion, who encourages the entire audience to “not only stoop, but with all humility lay both our hands and hearts at Your Majesty’s feet” (15–16).

Submitting to the audience of the public theater instead, Falstaff highlights the ways in which Shakespeare’s customers have usurped a place of authority formerly reserved for the queen. Falstaff goes on to note that “all the gentlewomen here have forgiven me” (2 Henry IV, epilogue, 22–23), a comment that conflates the women in the audience with that queen, implicitly inviting men to reach a different conclusion.135 By emphasizing the function of gender in the exercise of good judgment—only “good wenches” would place Falstaff among the “men of merit” who “are sought after” (2 Henry IV, 2.4.375)—the history plays call the queen’s qualification for good rule into question. At the same time, however, Shakespeare shares in Elizabeth I’s fondness for self-dramatizing old men, since his Sir John Paunch is no mere “Munsur Fatpanche.” A strong toil of affect (guilt, melancholy, nostalgia, admiration) modulates what had been, until Shakespeare came to it, a straightforward satiric trope. Even the coldly rational Hal finds that “were’t not for laughing” he “should pity” Falstaff (1 Henry IV, 2.2.110). Shakespeare turned the national pastime of baiting courtly old men into a profitable theatrical venture, a process that involved a recalibration of the theater’s relation to the structures of power and to the concepts of recreation and pleasure. Falstaff is the self-identified “lugg’d bear” who facilitates this transaction, but whose fecund charm, self-conscious wit, and inexhaustible talent for “shewes” also threaten to undermine it. Since drama, unlike polemics, thrives on ambiguity and conflict, this tension made for a successful stage formula. If early responses offer an indication, Falstaff achieved instant immortality, becoming a prime mover in establishing his author’s reputation and conjuring the enduring public to which we—along with Elizabeth I—belong.136

Fig. 5. George Gascoigne, The Noble Arte of Venerie or Hunting (1575), 133. By permission of the Folger Shakespeare Library.

Often disregarded in analyses of Falstaff, Merry Wives best illustrates Shakespeare’s conversion of scandalous material into renewable forms of theatrical pleasure. Perhaps the Cobham controversy emboldened the playwright to develop features of his knight left latent in 1 Henry IV. Although Falstaff eats and drinks to excess in that play, the erotic aspects of his surfeit are subsumed in a series of jokes and in his Endymion-like propensity for napping on stage. The Circe/Elizabeth figure associated with the age-in-love pattern is relegated to the margins of the play, where she takes the shape of the Welsh lady, whose speech is “as sweet as ditties highly penn’d / Sung by a fair queen in a summer’s bow’r” (3.1.206–7).137 In his perceptive analysis of 1 Henry IV, Garret Sullivan argues that the Circe myth haunts Shakespeare’s representation of the relation between Hal and Falstaff. While Sullivan contends that Falstaff plays “both tavern Circe and dangerous male favorite” to Hal, Falstaff himself casts Hal as the enchantress, at least if we take his observations that he is “bewitch’d with the rogue’s company” and that “the rascal” has “given me medicines to make me love him” (2.2.17–19) as referring to the young prince.138 Falstaff’s associations with bestiality, effeminacy, and idleness identify him, meanwhile, as a stereotypical victim to the classical goddess.139 Hal further emphasizes this pattern by bestowing animal monikers on his favorite and by categorizing Falstaff as a “latter spring” (1 Henry IV, 1.2.158), a preposterous old man who, having failed to observe the natural “race and course of age,” espouses lusty behavior inappropriate to “hys due tyme and season.”140

The patterns marking Falstaff as an aging lover in 1 Henry IV are concretized in 2 Henry IV and amplified in Merry Wives. Where in 1 Henry IV identifies Falstaff as “a whoremaster” (2.4.469), who “went to a bawdy-house not above once in a quarter—of an hour” (3.3.16–17), 2 Henry IV stages the lecherous (Leicesterous?) aspect of the royal favorite, and provides him with a “quean” who loves him “better than . . . e’er a scurvy young boy of them all” (2.4.272–73). And Merry Wives gives the amorous aspect of its aging antihero free reign: a “greasy knight,” “well-nigh worn to pieces with age,” Falstaff nevertheless determines to play the “young gallant” (2.1.108, 21–22). The command to show Falstaff in love (whether or not Elizabeth issued it) is thus far more perceptive, and the characterization of Falstaff more consistent, than critics normally allow.141 The farce returns the old man in lust to the context of female domination: the “female-controlled plotting . . . parallels the Queen-dominated court politics,” while magnifying “the pattern of provocation, deferral, prohibition, and frustration found in the cult of Elizabeth.” This is the context in which Falstaff—like the queen herself “inclining to threescore” (1 Henry IV, 2.4.425), and, as W. H. Auden remarks, way too old to be Hal’s favorite—belongs.142

From its opening conversation about upstarts and coats of arms, laced with sexual and bestial innuendoes, to its allusions to the Actaeon myth and the Order of the Garter, to its final restaging of the paradigmatic bearbaiting scene, Merry Wives tightens the connections between its antihero and Elizabeth’s amorous minions. Falstaff no longer operates at the safe remove of history: worried about appearing ridiculous to the “fine wits” and “the ear of the court” (4.5.100, 95), he blurs the distinction between the action on- and offstage, encouraging the audience to indulge in “pastimes.” The setting and the language of the play abet this process by situating the characters in comparative relation to offstage courtly figures, including Leicester, who had been “constable” (4.5.119) of Windsor from 1562 until his death, and the “radiant Queen” (5.5.46) who often resided in its castle, the seat of the Knights of the Garter. When he imagines one female target as “a region in Guiana, all gold and bounty” (1.3.69), Falstaff likens his amorous ambitions to those of Ralegh and Leicester, who had parlayed their status as royal minions into profitable new world ventures.143 The fat knight also imagines playing the “cheaters,” or escheater, to the wives’ “exchequers” (1.3.70–71), framing his sexual opportunism as a lucrative form of royal service. Elsewhere, Mistress Quickly asks us to judge Falstaff’s preposterous courting style against that of “the best courtier of them all (when the court lay at Windsor) who could never have brought her to such a canary; yet there has been knights, and lords, and gentlemen, with their coaches . . . they could never get her so much as sip on a cup with the proudest of them all, and yet there has been earls, nay (which is more) pensioners” (2.2.61–77). Even her malapropism—“canary” for “quandary”—recalls the specific earls and pensioners, who for all their “alligant terms” and “wine and sugar” (2.2.68), failed to secure the lady’s agreement: Leicester and Essex, who translated their courtship of the queen into the right to farm customs on the Mediterranean wines of which Falstaff is so fond.144 Merry Wives imagines Falstaff as one in a long line of such amorous and ambitious “knights, and lords, and gentlemen” who court in vain, arguably the most memorable, and certainly the largest, Elizabethan embodiment of “age in love.”

As Shakespeare’s promiscuous layering of allusions and references indicates, his repurposing of the age-in-love trope in Merry Wives does not weigh in on particular conflicts among courtiers. Rather, the play’s handling of this trope, and of the bearbaiting motif associated with it, clarifies that it became bound up for Shakespeare with broader issues of memory, judgment, empowerment, and recreation. While all the Falstaff plays imagine the transgressive old man as a baited animal, in Merry Wives this baiting structures the plot.145 Falstaff’s first appearance follows an extended reference to bearbaiting, a “sport” Slender loves well (1.1.290), which sets the scene for the “public sport” of punishing the “old fat fellow” (4.4.13–14) in the final act. Slender prides himself on having “taken” an actual bear “by the chain” (1.1.295–96) but the play awards the honor to its middle-class wives, who are immune to Falstaff’s courtship, discerning in their judgment of him, and resourceful in administering punishment.