On October 3, 1944, the Joint Chiefs of Staff issued a directive to Admiral Chester Nimitz, Commander in Chief Pacific (CINCPAC) to occupy the island of Iwo Jima. As with previous amphibious landings in the Marine Corps’ “island hopping” campaign, he entrusted the planning and implementation of the assault, codenamed Operation Detachment, to his experienced trio of tacticians – Spruance, Turner, and Smith – who had masterminded almost every operation since the initial landing at Tarawa in 1943.

Nimitz was a quiet somewhat introverted Texan who never lost a sea battle. President Roosevelt had been so impressed by him that he bypassed nearly 30 more senior admirals to appoint him CINCPAC after the removal of Admiral Husband E. Kimmel following the debacle at Pearl Harbor. One of Nimitz’s greatest abilities was to resolve conflicts with other senior officers. However, his long-running disputes with General Douglas MacArthur, Supreme Commander of all US Army units in the Pacific Theatre, were legendary. A man of striking contrasts, MacArthur was arrogant, conceited, egotistical, and flamboyant, and yet a superb strategist with an amazing sense of where and when to strike the enemy to greatest advantage.

Four Grumman Avenger torpedo-bombers unload their bombs in the area between Airfields Nos. 1 & 2. The cliffs of the Quarry overlooking the East Boat Basin can be seen in the foreground. (National Archives)

Nimitz and MacArthur disagreed throughout the war on the best way to defeat the Japanese, with MacArthur favoring a thrust through the Philippines and on to Formosa (Taiwan) and China. Nimitz stood by his “island hopping” theory – occupying those islands and atolls that were of strategic importance and bypassing those that had little military value or were unsuitable for amphibious landings.

Admiral Raymond A. Spruance had been Nimitz’s right-hand man since his outstanding performance at the Battle of Midway in June, 1942. His quiet unassuming manner concealed a razor sharp intellect and an ability to utilize the experience and knowledge of his staff to a remarkable degree. He would continue in the role of operations commander until the final battle of the Pacific War at Okinawa.

Admiral Richmond Kelly Turner, the Joint Expeditionary Force (JEF) commander, was by contrast notorious for his short temper and foul mouth, but his amazing organization skills placed him in a unique position to mount the operation. Dovetailing the dozens of air strikes and shore bombardments, disembarking thousands of troops and landing them on the right beach in the right sequence was an awesome responsibility fraught with the seeds of potential disaster, but Turner had proved his ability time and time again.

Fleet Admiral Chester Nimitz was appointed Commander-in-Chief Pacific (CINCPAC) after the Pearl Harbor debacle. A great organizer and leader, he was by the end of 1945 the commander of the largest military force ever, overseeing 21 admirals and generals, six Marine divisions, 5,000 aircraft, and the world’s largest navy. (US Navy)

Lieutenant-General Holland M. Smith, Commanding General Fleet Marine Force Pacific, “Howlin’ Mad” Smith to his Marines, was on the other hand nearing the end of his active career. His aggressive tactics and uncompromising attitude had made him many enemies. In America a powerful clique of publishing barons was running a vitriolic campaign against him in favor of General MacArthur, and his recent dismissal of the Army’s General Ralph Smith during the Saipan battle for “lack of aggressiveness” had not endeared him to the top brass in the Pentagon. At Iwo Jima he was content to keep a low profile in favor of Major-General Harry Schmidt, V Amphibious Corps Commander: “I think that they only asked me along in case anything happened to Harry Schmidt,” he was to say after the battle.

The Iwo Jima landing would involve an unprecedented assembly of three Marine divisions: the 3rd, 4th, and 5th. Heading the 3rd Division was Major-General Graves B. Erskine, at 47 a veteran of the battles of Belleau Wood, Chateau Thierry, and St Mihiel during World War I. Later he was the chief of staff to Holland Smith during the campaigns in the Aleutians, Gilbert Islands, and the Marianas.

The 4th Division was also commanded by a World War I veteran, Major-General Clifton B. Cates, who had won the Navy Cross and two Silver Stars. At Guadalcanal in 1942 he had commanded the 4th Division’s 1st Regiment and at Tinian became the divisional commander. In 1948 he became the Commandant of the Marine Corps.

Lieutenant-General Holland M. Smith, “Howlin’ Mad” to his Marines, was a volatile leader who did not suffer fools gladly. His dismissal of Army general Ralph Smith during the Saipan operation was to cause friction between the Army and the Marines for years. Seen here in two-toned helmet alongside Secretary of the Navy James Forrestal (with binoculars) and a group of Iwo Jima Marines. (National Archives)

Major-General Keller E. Rockey was another Navy Cross holder for gallantry at Chateau Thierry. He won a second Navy Cross for heroism in Nicaragua in the inter-war years and took command of the 5th Division in February 1944. Iwo Jima was to be the division’s first battle, but it boasted a strong nucleus of veterans of the recently disbanded Raider Battalions and Marine Paratroopers.

Responsibility for preparing and executing Marine operations for Detachment fell to V Amphibious Corps Landing Force Commander Major-General Harry Schmidt. A veteran of pre-war actions in China, the Philippines, Mexico, Cuba, and Nicaragua and later the 4th Division commander during the Roi-Namur and Saipan invasions, he was 58 years old at Iwo Jima and would have the honor of fronting the largest Marine Corps force ever committed to a single battle.

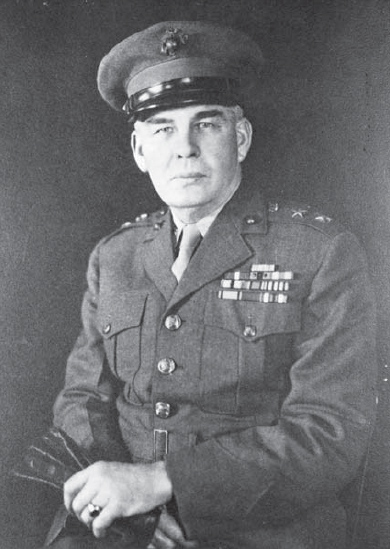

“The Dutchman,” Major-General Harry Schmidt, was to command V Amphibious Corps, the largest force the Marine Corps had ever put in the field. A veteran of numerous inter-war actions ranging from China to Nicaragua, he was 58 years old at the time of the battle. (USMC)

In May, Lieutenant-General Tadamichi Kuribayashi had been summoned to the office of the Japanese prime minister, General Tojo, and told that he would be the commander of the garrison on Iwo Jima. Whether by accident or design the appointment proved to be a stroke of genius.

Kuribayashi, a samurai and long-serving officer with 30 years of distinguished service, had spent time in the United States as a deputy attaché and had proclaimed to his family: “the United States is the last country in the world that Japan should fight.” He looked upon his appointment as both a challenge and a death sentence. “Do not plan for my return,” he wrote to his wife shortly after his arrival on the island.

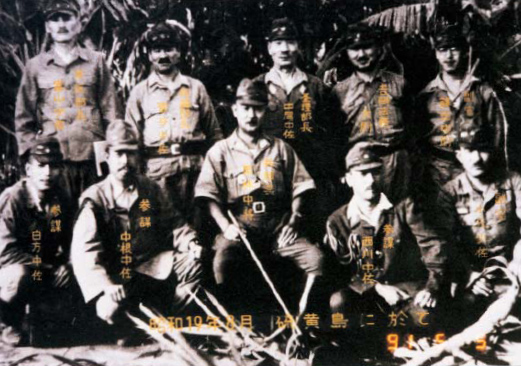

Kuribayashi and his staff had time to pose for a formal group photograph before the Americans arrived. None was to survive the battle. (Taro Kuribayashi)

Kuribayashi succeeded in doing what no other Japanese commander in the Pacific could do – inflict more casualties on the US Marines than his own troops suffered. Fifty-four years old at the time of the battle and quite tall for a Japanese at 5ft 9ins (1.75m), Radio Tokyo described him as having the “traditional pot belly of a Samurai warrior and the heart of a Tiger.”

Lieutenant-General Holland Smith in his memoirs was lavish in his praise for the commander’s ability:

His ground organization was far superior to any I had seen in France in WWI and observers say it excelled the German ground organization in WWII. The only way we could move was behind rolling artillery barrages that pulverized the area and then we went in and reduced each position with flamethrowers, grenades and demolition charges. Some of his mortar and rocket launchers were cleverly hidden. We learned about them the hard way, through sickeningly heavy casualties. Every cave, every pillbox, every bunker was an individual battle where Marines and Japanese fought hand to hand to the death.