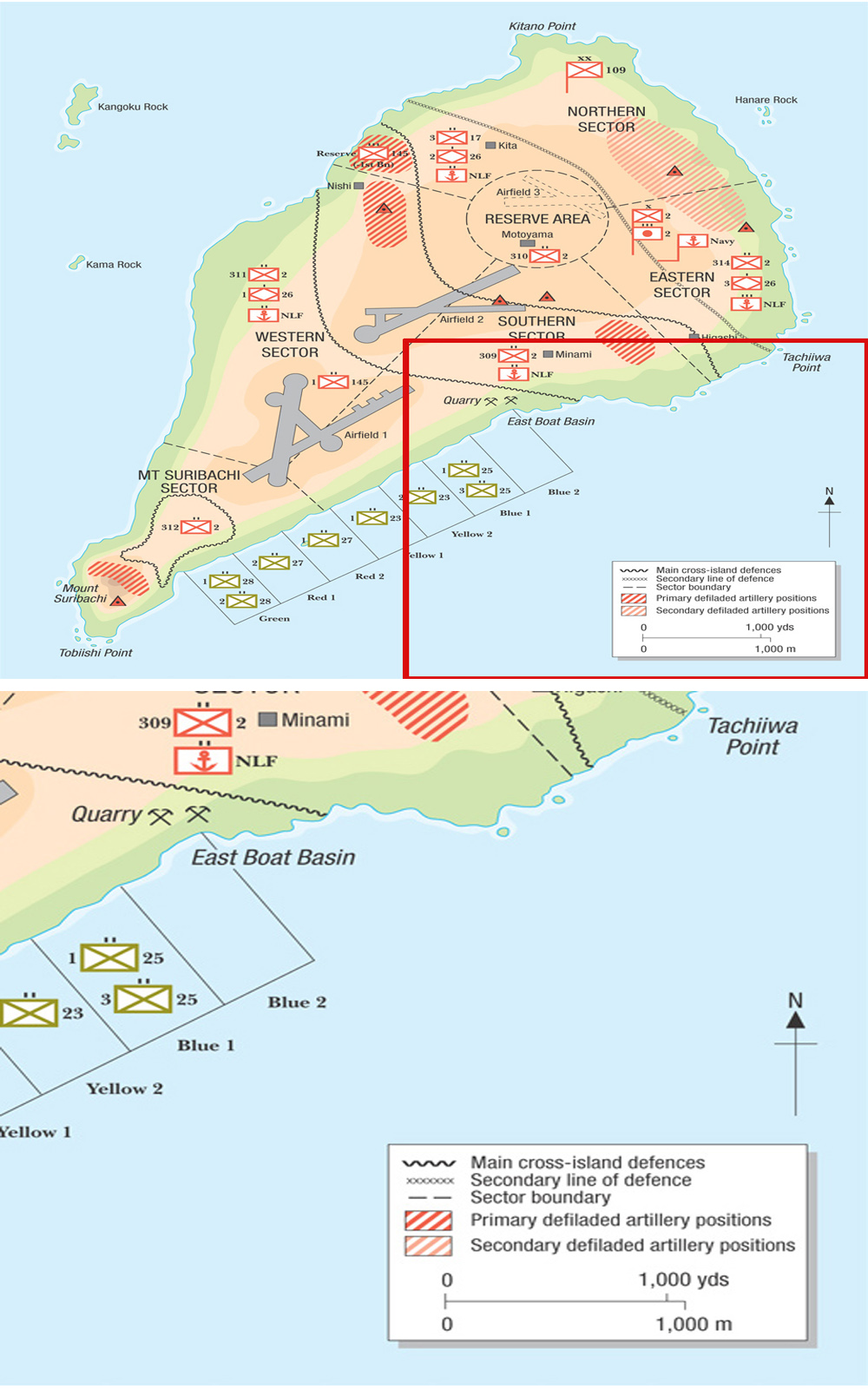

The plan of attack that was devised by V Amphibious Corps planners looked simple. The Marines would land on the 2-mile (3.2km) long stretch of beach between Mount Suribachi and the East Boat Basin on the southeast coast of the island. These beaches were divided into seven sections of 550 yards (914m) each. Under the shadow of Suribachi lay Green Beach (1st and 2nd Battalions, 28th Regiment), flanked on the right by Red Beach 1 (2nd Battalion, 27th Regiment), Red Beach 2 (1st Battalion, 27th Regiment), Yellow Beach 1 (1st Battalion, 23rd Regiment), Yellow Beach 2 (2nd Battalion, 23rd Regiment), Blue Beach 1(1st and 3rd Battalions, 25th Regiment). Blue Beach 2 lay directly under known enemy gun emplacements in the Quarry overlooking the East Boat Basin, and it was decided that both the 1st and 3rd Battalions of the 25th Regiment should land abreast on Blue Beach 1. General Cates, the 4th Division commander, said: “If I knew the name of the man on the extreme right of the right hand squad (on Blue Beach), I’d recommend him for a medal before we go in.” The 28th Regiment would attack straight across the narrowest part of the island to the opposite coast to isolate and then secure Mount Suribachi. On their right, the 27th Regiment would cross the island and move to the north, while the 23rd Regiment would seize Airfield No. 1 and then thrust northward towards Airfield No. 2. The 25th Regiment, on the extreme right, would deploy to their right to neutralize the high ground around the Quarry overlooking the East Boat Basin.

General Kuribayashi’s first priority was to reorganize the archaic defense system that was in place when he arrived, a defense system that he recognized was completely inadequate to cope with the future US onslaught. All civilians were sent back to the mainland as their presence could serve no useful purpose and they would be a drain on the limited supplies of food and water. With the arrival of more troops and Korean laborers he instigated a massive program of underground defenses. A complex and extensive system of tunnels, caves, gun emplacements, pillboxes, and command posts was constructed in the nine months prior to the invasion. The soft pumice-like volcanic rock was easily cut with hand tools and mixed well with cement to provide excellent reinforcement. Some tunnels were 75ft (23m) under ground, most were interconnecting, and many were provided with electric or oil lighting.

Supply points, ammunition stores, and even operating theaters were included in the system and at the height of the battle many Marines reported hearing voices and movements coming from the ground beneath them. When Mount Suribachi was isolated many of the defenders escaped to the north of the island, bypassing the Marine lines through this labyrinth of tunnels.

The tunnels were constructed at an unprecedented speed. The specification called for a minimum of 30ft (9.1m) of earth overhead to resist any shell or bomb. Most were 5ft (1.5m) wide and the same high with concrete walls and ceilings and extended in all directions (one engineer in his diary said that it was possible to walk underground for 4 miles / 6.4km). Many tunnels were built on two or even three levels and in the larger chambers, airshafts of up to 50ft (15.2m) were needed to dispel the foul air. Partially underground were the concrete blockhouses and gun sites, so well constructed that weeks of naval shelling and aerial bombing failed to damage most of them; and the hundreds of pillboxes, which were of all shapes and sizes, were usually inter-connected and mutually supporting.

The complexity of the underground tunnel system can be judged from this picture of one of the existing passages. (Taro Kuribayashi)

The Japanese general had studied earlier Japanese defense methods of attempting to halt the enemy at the beachhead and had realized that they invariably failed, and he regarded the traditional banzai charge as wasteful and futile. In September at Peleliu the Japanese commander, Lieutenant-General Inoue, had abandoned these outdated tactics and concentrated on attrition, wearing down the enemy from previously planned and prepared positions in the Umurbrogol Mountains. Kuribayashi approved of these tactics. He knew that the Americans would eventually take the island but he was determined to exact a fearful toll in Marine casualties before they did.

The geography of the island virtually dictated the location of the landing sites for the invasion force. From aerial photographs and periscope shots taken by the submarine USS Spearfish, it was obvious that there were only two stretches of beach upon which the Marines could land. Kuribayashi had come to the same conclusion months earlier and made his plans accordingly.

Iwo Jima is some 4½ miles (7.2km) long with its axis running from southwest to northeast, tapering from 2½ miles (4km) wide in the north to a mere ½ mile (0.8km) in the south, giving a total land area of around 7½ square miles (19.4 square km). At the southern end stands Mount Suribachi, a 550ft (168m) high dormant volcano that affords commanding views over most of the island, and the beaches that stretch northward from Suribachi are the only possible sites for a landing.

On a plateau in the center of this lower part of the island the Japanese built Airfield No. 1, and further north a second plateau roughly a mile in diameter housed Airfield No. 2 and the unfinished Airfield No. 3. The ground that slopes away from this northern plateau is a mass of valleys, ridges, gorges, and rocky outcrops that provide an ideal site for defensive fighting.

Major Yoshitaka Horie, staff officer to Kuribayashi, had many discussions with his superior about the role of anti-aircraft guns. Horie was of the opinion that they would be far better employed as artillery or in an antitank role as it was obvious that the Americans would have overwhelming air superiority before and during the battle. His reasoning seems to have impressed the general, who overruled the objections of some of his staff officers and implemented some of Horie’s ideas.

Horie was interviewed by a Marine officer after the war and his comments were recorded for the Marine Corps Historical Archives. He told General Kuribayashi:

We should change our plans so that we can use most of the antiaircraft guns as artillery and retain very small parts of them as antiaircraft guns. Antiaircraft guns are good to protect the disclosed targets, especially ships, but are invaluable for the covering of land defenses.

The staff officers had different opinions.

The staff officers were inclined as follows; they said at Iwo Jima it is good to use antiaircraft guns as both artillery and antiaircraft guns. The natural features of Iwo are weaker than of Chichi Jima. If we have no antiaircraft guns, our defensive positions will be completely destroyed by the enemy’s air raids... And so most of the 300 anti-aircraft guns were used in both senses as above mentioned, but later, when American forces landed on Iwo Jima, those antiaircraft guns were put to silence in one or two days and we have the evidence that most antiaircraft guns were not valuable but 7.5cm antiaircraft guns, prepared as antitank guns, were very valuable.

Horie, in his curious English, went on to describe the initial Japanese reaction to the landings:

With Mount Suribachi in the foreground, the invasion beaches can be seen on the right of the picture, stretching northwards to the East Boat Basin. Isolating the volcano was the number one priority for the Marines and involved crossing the half-mile neck of the island as rapidly as possible. (US Navy)

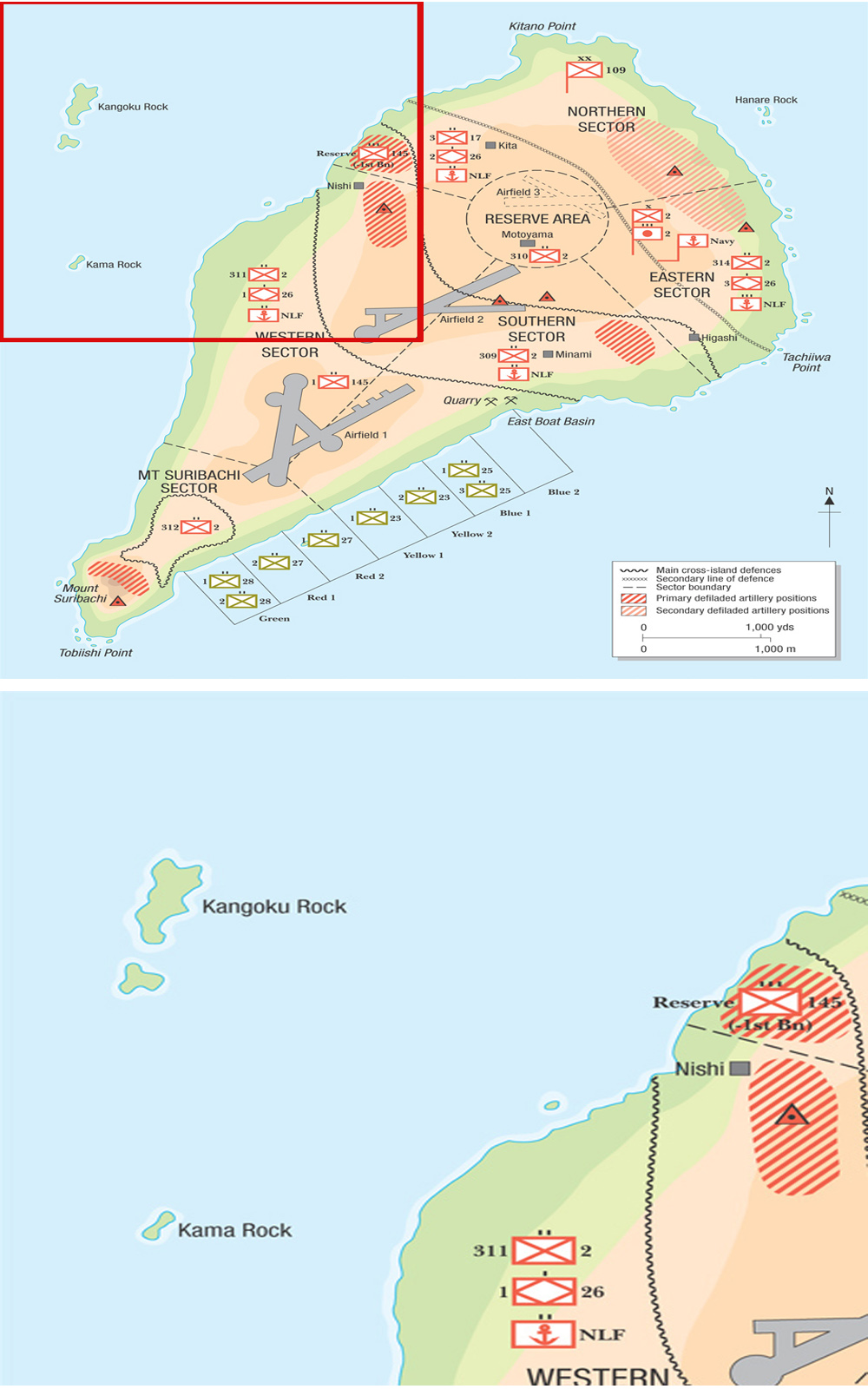

Japanese defense sectors and US landing beaches. Note how the Mount Surbachi area was confined in the south of the island – capturing this was just the beginning of the campaign to secure Iwo Jima.

On the February 19, American forces landed on the first airfield under cover of their keen bombardments of aircraft and warships. Although their landing direction, strength and fighting methods were same as our judgment, we could not take any countermeasures towards them, and 135 pillboxes we had at the first airfield were trodden down and occupied in only two days after their landing.

We shot them bitterly with the artillery we had at Motoyama and Mount Suribachi, but they were immediately destroyed by the enemy’s counter-firing. At that time we had opportunity to make offensive attacks against the enemy but we knew well that if we do so we will suffer many damages from American bombardments of aircraft and vessels, therefore our officers and men waited the enemy coming closer to their own positions.