3.

Provocateurs and Pagans

Mostly 1440–1550

Lorenzo Valla questions everything—Cicerolatry, paganism, and Rome—Pomponio Leto and Bartolomeo Platina, who annoyed a pope—Tuscany, especially Florence—Pico della Mirandola and the human chameleon—Leon Battista Alberti and the universal man—the human measure again—Vitruvians—Girolamo Savonarola burns the vanities—Sack of Rome—portraits—everything in question.

When the emperor Constantine the Great fell ill with leprosy sometime around 315 CE, he was all set to treat himself with the conventional remedy of bathing in children’s blood, but a dream told him to seek help from Pope Sylvester I instead. He obeyed; the pope blessed him, and his leprosy disappeared. Constantine showed his gratitude by granting the pope and his successors dominion over all the western territory of Europe, including the Italian peninsula. The emperor had the gift recorded in a document known as the Donation of Constantine. The scene of the signing was immortalized later in a Vatican fresco painted by pupils of Raphael in the 1520s: you can stand in front of it and see with your own eyes how it happened.

Except that it didn’t—a fact that was already well known at the time the fresco was done. The leprosy story was just a story, and the document was a forgery, apparently produced in the eighth century and used later to strengthen the papacy’s land claims while also justifying German emperors’ desire to call themselves Holy Roman Emperors. The Donation document had drawn skeptical attention for a while. But the most thorough debunking was done by a fifteenth-century literary humanist, who brought all his century’s intellectual effervescence to the task.

His name was Lorenzo Valla, and his 1440 treatise On the Donation of Constantine is one of the great humanist achievements. It combines a precise scholarly assault with the high rhetorical techniques learned from the ancients, served up with a sauce of hot chutzpah. All these assets were necessary to Valla, because he was daring to attack one of the church’s central modern claims: its justification for having complete power over all of western Europe. It could be a short step from that to questioning its other claims to authority, too, including the authority it held over people’s minds.

Valla seems to have been a man who had no fear and could never be persuaded to keep quiet. He traveled all over Italy, working for a series of patrons and supporters—at this point he was living in Naples—but he made enemies everywhere as well. The poet Maffeo Vegio had already warned him to seek advice before writing things that would hurt people’s feelings, and generally to restrain his “intellectual violence.” This he could or would not do. Valla’s energies burst out of his body: another scholar, Bartolomeo Facio, summed him up by saying that he held his head high, he never stopped talking, he gesticulated with his hands, and he walked excitedly. (In Facio’s beautifully concise Latin, this can be said in just eight words: “Arrecta cervix, lingua loquax, gesticulatrix manus, gressus concitatior.”) Valla acknowledged his own bumptious character: in a letter, he admitted that he took on the Donation task partly for the sheer fun of displaying his abilities: “to show that I alone knew what no one else knew.”

His attack begins in that sort of tone. He addresses the pope directly: I will show, he says, that this document is illegitimate and that claims based on it are false. He throws in jaunty insults against anyone else who has been fooled by the deception: “You blockhead, you dolt!” (“O caudex, o stipes!”). In fact, this way of opening the argument is also a well-calculated rhetorical strategy, grabbing the reader’s attention. Having done this, he goes on to more focused arguments. First he uses the methods of a historian, inquiring into plausibility and evidence. Is it likely, he asks, that a ruler such as Constantine would have given away so much territory from his empire? And: Has anyone ever seen supporting documentation of Pope Sylvester’s having accepted such a gift? In both cases, the answer is no.

Following these blows from rhetoric and historical reasoning, the third and last weapon in the strategic sequence is the killer one: philology, or the analysis of language. Valla shows that the document’s Latin is not correct for the fourth century. He lists anachronistic blunders, as in one passage featuring the phrase “together with all our satraps” (“cum omnibus satrapis nostris”). Roman officials were not referred to as “satraps” until the eighth century. Another passage uses banna for “flag,” but a pre-medieval writer would have said vexillum. The term clericare, with the meaning “to ordain,” is not of the fourth century. He also points out such absurdities as a reference to udones, which for Romans were “felt socks,” yet the text describes them as made of white linen. Felt is nothing like linen, says Valla, and it is not white. He rests his case.

Valla knew he was on firm ground as an expert Latinist (and a Hellenist, too: he later translated works by Homer, Thucydides, and Herodotus). The most influential of his works would be a style manual of good Latin, Elegances of the Latin Language, on which generations of later students came to rely in their compositions. “How brilliant Valla is!” gushed one of the many who learned from it. “He has raised up Latin to glory from the bondage of the barbarians. May the earth lie lightly on him and the spring shine ever round his urn!”

The Elegances took on the task of scraping off the medieval barnacles that had grown on the ancient language and starting again with truer, more original models instead. That notion also drove the Donation project, only in that case the whole thing was a barnacle. An alternative image for such a process might be digging out weeds, which was how Valla had presented a work written shortly before his Donation: the strikingly named Repastinatio dialecticae et philosophiae. The title means something like a hoeing or redigging of dialectic and philosophy. It made the case for turning over the medieval clods to get down to a more fertile field where truth might grow, even if this entailed upending such peacefully sleeping authorities as Aristotle, who had been much revered in previous centuries. Valla also redug the texts that were more revered by fellow humanists of his own time, as with the series of Amendments he produced to surviving books of Livy—of which he had Petrarch’s personally edited copy to hand. He did the same even to the Bible. In his Annotations to the New Testament, he identified defects in the standard Latin translation of the Greek New Testament made in the fourth century by Jerome. Again, using his ability to think historically about processes and origins, Valla went beyond just pointing out errors to speculating about how they might have crept in, for example, by confusion arising from similar-looking Greek letters.

Risking enmity from old-style Aristotelian scholars, or from modern humanists, or from church authorities: none of it seemed to deter Valla. Of these opponents, the last was the most dangerous one to rouse. Sure enough, in 1444 he would become the target for an investigation by the Inquisition of Naples. Its main problem was not with his Donation but with some of his other unorthodox views on the Christian Trinity and on the question of free will—and on the ancient, very un-Christian philosophy of Epicureanism, which recommended living wisely and well in the present life rather than worrying about the beyond.

Valla had written the work that flirted with danger on this topic back in 1431: a dialogue called De voluptate (On Pleasure). This featured three speakers giving their views on that subject in turn. First, a Stoic says that all is misery and there can be no pleasure for human beings at all. “Oh, if only we had been born animals instead of men. If only we had not been born at all!”

Then an Epicurean puts the opposite case. Life is full of pleasurable and beautiful experiences, he says, such as listening to the voice of a woman speaking sweetly or tasting good wine. (I myself, he digresses, have cellars filled with the best vintages.) There are deeper pleasures, too, such as those that come from having a family, holding public office, and lovemaking. (He has a lot to say about this last one.) Even better is the self-satisfied glow that comes from knowing how virtuous one is: that is just another kind of pleasure.

A third speaker argues for the Christian view: pleasure is nice, but it is better to seek heavenly pleasures instead of worldly ones. The Christian is allowed to keep the last word and win the case, but it is hard not to notice the sympathetic treatment the Epicurean receives along the way, especially at one moment when the character of Lorenzo (that is, the author) is shown whispering to him, “My soul inclines silently in your direction.”

Indeed, this was noticed. When the first version of the work attracted controversy, Valla adjusted it slightly, renaming characters, moving the scene from Rome to Pavia, and changing its title from On Pleasure to the more spiritually uplifting De vero bono—On the True Good. He sent the Christian final part to Pope Eugenius IV as a gift, but with a typically cheeky cover letter: “What in Heaven’s name could afford you more pleasure than this book?” The letter goes on to ask for money.

So there were plenty of reasons in 1444 for the Naples Inquisition to want to Inquire into Valla. He was saved almost immediately, however, because his patron and protector, King Alfonso of Naples, intervened to stop the process. The king owed him: Valla had been part of his court entourage for some time and always lent his eloquence to helping the king’s interests. As an itinerant humanist, of course, Valla had to please his current protector, just as Petrarch had. That was one of the main reasons—besides philological purism—for writing his Donation: at the time, Alfonso had been trying to defend his territory against attempts by Pope Eugenius in Rome to encroach on its borders. By undermining all such territorial claims from Rome in general, Valla was aiding that objective. I don’t think this takes anything significant away from the achievement: Valla still loved cleaning up texts as a matter of principle. By bringing his fearless, scholarly questioning of authority to bear on the bogus Donation, and pleasing his patron, Valla also managed to save himself from the consequences of all the other fearless and scholarly questioning he had done.

The post in Naples did not last forever; humanists’ positions rarely did. In the end, Valla found a substitute in the last place you might expect: in Rome, with a new pope. Succeeding Eugenius in 1447, Nicholas V was much more sympathetic to humanistic ideas and activities than his predecessor. Valla now secured a berth in the Curia (the papal court) as an apostolic scriptor, or scribe. This allowed him to live in Rome; he would also be appointed a professor of rhetoric at its university and go on to be a secretary to the next pope, Calixtus III, who also gave him a canonry at the papal basilica of St. John Lateran. You could hardly ask for a more typical array of humanist positions: royal court, church, and university, all smoothly woven into the life of a man who still managed to keep himself mostly devoted to free, bold investigations on his own terms.

But his life never became entirely relaxed or easy, and neither did his earthly afterlife. When he died in 1457 at the age of fifty, his mother—who survived him—arranged for a fine tombstone to be created in the basilica, with an inscription praising his eloquence. At some point, probably in the mid-sixteenth century, when the Reformation made the church extra-sensitive to anyone who had criticized it, the tomb was removed and placed out of sight somewhere. From there, it descended to further indignities. The German historian Barthold Georg Niebuhr, visiting Rome in 1823, was astonished to see Valla’s memorial stone in the street being used as a paving slab—the same fate that had met so many other insufficiently Christian hunks of stone. It was rescued shortly afterward and moved to a safer place back inside the basilica, where it still is.

Valla’s real monument was his works, but, like the memorial stone, they were also repurposed in unpredictable ways. His commentary on the New Testament seemed to be forgotten, until Erasmus found a manuscript copy in an abbey library and edited it for publication in 1505—a book-discovery story in the Petrarchan tradition, but this time of a modern work that had served its “prison” sentence for only a few decades. That discovery helped inspire Erasmus to do his own new translation of the New Testament. Like Valla, he preferred to work from old, clean sources, partly because of general pride in good scholarship and partly because he also believed that Christianity was a better thing before it became so preoccupied with its own institutional power.

Neither Erasmus nor Valla would have pursued that argument as far as did a new breed in Erasmus’s time: the Protestants. In their rejection of church authority, they seized on Valla’s treatise as a support. That at least was the motive of the German Ulrich von Hutten when, in 1517, he issued a new, printed version with an overtly antipapal purpose. No wonder Pope Julius II felt the need to commission the Vatican fresco at that time: it was a way of hammering home the Constantine story, while simply ignoring the fact that it had already fallen victim to the humanist harpoon.

Later still, with religious conflicts becoming less prominent, other generations of intellectuals were drawn to Valla just because they admired his methods and his goals. For them, he came to represent freethinking in the most general sense of that word—that is, the insistence on trusting expertise rather than authority and on exploring how texts and claims came to be the way they were. They would follow him in investigating suspicious documents and analyzing their origins and validity. Later still, non-religious humanists (thus, “freethinkers” in a more specific sense) would also recognize something of themselves in Valla’s outspoken attitude and his apparent sympathy for Epicurean ideas.

Even his wild and bellicose manner has had a certain appeal, especially because he made a kind of philosophy of it. In a letter, he laid out his vision of universal contrarianism, asking, “Who has ever written on any field of learning or science without criticizing his predecessors?” Aristotle, for example, was criticized by his student and nephew Theophrastus. “Indeed, as far as I recall from my extensive reading, I can hardly find an author who does not at some point refute or at least reproach Aristotle.” By doing that, they are following no less a model than Aristotle himself, who also took issue with his own former teacher, Plato—“Yes, Plato, the prince of philosophers!” Turning to Christian writers: Augustine criticized Jerome, and Jerome attacked older church authorities, saying that their interpretations themselves required interpretation. Physicians criticize each other and give different diagnoses. Sailors, when a storm looms, can never agree on how best to steer the ship. As for philosophers: “What Stoic can resist challenging nearly everything an Epicurean says, only to suffer the same from him in return?” Dispute and contradiction, not veneration and obedience, are the essence of intellectual life. And, crucially, Valla did not merely tell people they were wrong; he gave them the reasons why they were wrong.

As he concluded this letter: sometimes fighting with the dead is one’s duty, because it benefits those who will follow. And that is a matter of duty, too: one must train the young and also, where possible, “restore the others to their senses.”

The young did flock to Valla in search of his instruction. Poggio Bracciolini, who was among his enemies, complained that Valla was setting students a bad example by his constant picking of holes in even the most revered works, such as the classical rhetoric manual Rhetorica ad Herennium. Valla seemed to fancy himself “superior to any ancient writer,” complained Poggio. He added violently that one would need “not words but cudgels, and Hercules’ club, to beat down this monster and his pupils.”

One reason Poggio had such respect for the Rhetorica ad Herennium was that it was thought to be by Cicero, although in fact this was the wrong attribution. (The real author is unknown.) And Poggio was one of a series of humanists who considered Cicero so eminent and perfect as to be beyond attack by any mere mortal. He thus took the opposite side from Valla in a long-running battle of many minds, concerning a question that sounds ridiculous now but seemed of great importance then. Should Cicero be the only guide to Latin style worth following, or might one emulate other classical authors, too? A few humanists were so dedicated to the first alternative that they swore—perhaps partly in jest—to use no word in their own writing that could not be found in their hero’s works. If it wasn’t in Cicero, it wasn’t Latin.

Behind this lay a whole tradition of humanist Cicerolatry. Petrarch, who was less uncritical in his admiration, amused himself at the expense of a friend who was so deeply pained by hearing attacks on the great orator that he exclaimed, “Gently, please, gently with my Cicero!” The friend then admitted that, for him, Cicero was a god. That’s a funny thing for a Christian to say, remarked Petrarch. The friend hurriedly explained that he meant only “a god of eloquence,” not an actual divine being. Ah! said Petrarch, then if Cicero was only human, he could have flaws—and did. The friend shuddered and turned away.

That was part of the problem: treating Cicero as superhuman implied setting him on a level comparable to that of Jesus Christ himself. If that sounds like overstretching the case, consider a dream reported by the biblical translator Jerome a millennium earlier. While living in a hermit’s retreat near Antioch, feverish from starvation and determined to give up classical authors and all other worldly pleasures, Jerome dreamed that he was summoned before Jesus, sitting as judge.

“What condition of man are you?” asked Jesus.

“I am a Christian,” replied Jerome.

“You lie,” replied Jesus. “You are not a Christian but a Ciceronian.” He had him whipped for it, and when Jerome woke up, he swore never again to own or read a non-Christian book.

In reality, Jerome did continue referring to such books in his work. Commenting on this, Lorenzo Valla generously suggested that it was okay, because Christ had banned him only from using Cicero’s philosophy, not from citing or imitating him as literature. Valla himself had no aversion to reading Cicero. It was merely that he thought other literary models were just as good, and maybe better—especially Quintilian, whom he greatly admired.

All these people loved their classics, but this long series of Ciceronian quarrels shows a rift appearing between two types of humanists: those who adored and imitated certain long-lost authors unquestioningly, and those who considered nothing beyond question, not even Cicero (or, indeed, the pope). It is no surprise to find Valla on the latter side. Besides his general spirit of inquiry, he had a good reason for approaching writers historically rather than seeing them as timeless models. If everyone really did start writing like Cicero, it would be impossible for those such as Valla ever to date a piece of writing by internal evidence again. All texts would sound the same, and philologists would be finished.

Fortunately, there will always be slipups that give imitators away. One of the most extreme Ciceronians was Christophorus Longolius, born Christophe de Longueil in the Low Countries in 1490. But he betrayed his difference from Cicero every time he used his own first name, whether in Latin or vernacular form, since Christophorus means “Christ-bearer,” a word that Cicero, who died in 43 BCE and knew nothing of Christ, could not have used.

Longolius’s problem was pointed out in a satirical dialogue by Erasmus, The Ciceronian, published in 1528. Two friends are trying to talk a third out of joining the fad, so they run through a list of all the writers who have tried it and failed. For a moment they think they have found one successful case in Longolius, until it dawns on them that his name makes it impossible. Erasmus is having fun at the expense of fanatics here, but he also makes a serious point. If Ciceronians cannot allow themselves to speak of any Christian subject, what does that imply about their belief system? Ciceronianism might be a sign of a secret, subversive “paganism” in the heart of the modern Christian world.

This word pagan, originally meaning “peasant” or “country bumpkin,” was used by Christians to describe all pre-Christian religion, but especially that attached to the old Roman gods. Relations between the two traditions had always been strained, hence the eagerness of early Christians to literally stamp the Roman temples and statues out of the landscape. The relationship mellowed with time, however. It became clear that pagan traditions were so interwoven with Christian ones in European culture that they could not be fully untangled again. The very stones of Rome were pagan in origin, and Roman and Greek mythology was so full of good stories that artists, in particular, could never resist it—especially when it featured love goddesses emerging from seashells wearing floaty, translucent clothes. Perhaps, rather than trying to wipe out the pagan tradition, it was better to try to assimilate and Christianize it.

That process necessitated some mental athletics. Petrarch reassured himself that Cicero, if only he had had the chance, would have been a good Christian. Others tried to reinterpret classical works as prophecies of the coming religion. Virgil lent himself well to this. His Fourth Eclogue mentions a new age on its way and the birth of a special boy: could that be Jesus? And Aeneas’s round trip to the Underworld of death, in the Aeneid: was that not an allegory of the Resurrection? Back in the fourth century, the poet Faltonia Betitia Proba, herself from a prominent family of pagan-to-Christian converts, had managed to assemble enough bits of Virgil to form a whole narrative telling the story of the Creation, Fall, and Flood, as well as Jesus’s life and death. In the end, though, Virgil himself still had the misfortune of having been born too early to be saved. This is why Dante, despite relying on him as his guide through Hell and Purgatory in the Comedy, cannot let him continue as far as Paradise. He tells us that Virgil’s usual home is in Limbo, a not too unpleasant first circle of Hell where other good pagans live, unlike such bad pagans as Epicurus (and all his followers), deep inside the sixth circle.

Ciceronians tried similar merging of pagan and Christian terms to get around their problem, such as referring to the Virgin Mary as the goddess Diana. But suspicion continued to hang over them. As Erasmus had one of his characters ask another: Have you ever seen a crucifix displayed in any of these classicists’ precious private museums of antiquities? The speaker answers himself: “No, everything is full of the monuments of paganism.” Given a chance, he says, they would probably bring it all back—“the flamens and vestals, . . . the supplications, the temples and shrines, the feasts of couches, the religious rites, the gods and goddesses, the Capitol and the sacred fire.”

The thing is, Erasmus was clearly right, at least about some of the earlier Ciceronians. During the 1460s, several men in Rome had begun meeting up in what came to be called an “Academy,” an allusion to Plato’s ancient “Academy,” or school, in Athens. In the Ciceronians’ case, their interests were less focused on Greece than on the pre-Christian world of their own city. There was some serious history involved: the group included eminent scholars with university jobs, and they delivered lectures and gave tours of Rome’s ruins. Petrarch would have loved to join such a tour. Perhaps Erasmus would have gone along, too, but he and Petrarch alike would have been shocked by some of the group’s wilder evening events. They met amid the ruins, dressed up and put laurel wreaths on their brows, and enacted ancient festivities. They also recited their own Latin poems, including love poetry addressed to each other or to younger men. They put on comedies by Plautus or Terence—a daring venture, as Christianity had disapproved of non-devotional theatrical performances ever since Justinian closed the theaters in the sixth century. The prime mover behind many of these spectacles was one Giulio Pomponio Leto, or Julius Pomponius Laetus, a professor of rhetoric originally from Naples. “Laetus” was a name of his own choice; it means “happy.”

Happy professors cavorting by moonlight, declaiming love poems to one another, putting on theatrical extravaganzas: was it all . . . quite . . . Christian? Well, most of the Academy’s members were employed or otherwise involved in various ways with the papal court, sometimes in combination with their other posts, so one would think so. But many intellectuals in the city held a paid role in the church, and it did not necessarily mean much. A report sent home by a Milanese ambassador alleged that their true beliefs were very different: “The humanists denied God’s existence and thought that the soul died with the body,” he wrote, adding that they considered Christ to be a false prophet.

With their adulation of the Rome of the Republic—of Cicero’s time—they could also look seditious in other ways. Some onlookers suspected that they wanted to restore the republican political system, perhaps through an uprising or revolution. This was plausible: such a feat had previously been tried by an acquaintance of Petrarch’s, Cola di Rienzo, another enthusiast for the city’s ruins and inscriptions. After early failed attempts, he successfully overthrew the city’s ruling barons and set himself up as a consul in the old Roman style, with a certain amount of public support—though that was short-lived, as was he. In 1353, the mood shifted, and a crowd assembled outside his palace, chanting, “Death to the traitor Cola di Rienzo!” He escaped the building in disguise and mingled with them, trying to blend in by shouting the same thing, but he was recognized, stabbed, and taken away to be hanged. Some people now wondered whether the Academicians had it in mind to see if a similar coup could have more success a second time around.

Hostility began to gather around them. At first, they remained safe in their various secretarial and clerical posts in the Curia, because the pope of the time, Pius II, was himself a humanistic and studious man who appreciated their interest in antiquity. Things changed in 1464, when the next pope succeeded him: Paul II. He had no understanding of the things humanists cared about and no respect for their studies or skills. Above all, he disliked any whiff of paganism, despite the fact that he also had a taste for lavish processions that merged classical and Christian imagery. A deeper interest in the ancients was less to his taste. It was better to be devoutly ignorant, he said, than to fill young heads with heresy and tales of sexual immorality. “Before boys have reached the age of ten and gone to school, they know a thousand immodesties; think of the thousand other vices they will learn when they read Juvenal, Terence, Plautus, and Ovid.” (In truth, you didn’t need classical literature to learn vices: according to a dialogue on hypocrisy by Poggio, one preacher often provided so much detail in his sermons against lust that the congregation rushed home afterward to try out the practices for themselves.)

Disliking the humanists, and wanting to save on their cost, Paul II abolished their secretarial and other jobs at the Vatican. But people who had such posts had usually paid a sum to get them in the first place, so the humanists complained about being swindled. Now that they were protesting, they sounded more like rebels than ever. One of them, named Bartolomeo Sacchi but known as “Platina” after his hometown of Piadena, was arrested for his outspokenness and spent four months in the papal prison in the Castel Sant’Angelo. He was released, but in February 1468, the pope ordered about twenty Academy members to be rounded up, including Platina again. They were charged with conspiracy, heresy, sodomy, and other crimes and put through the castle’s torture chambers. Platina suffered permanent damage to his shoulder from the strappado, a hideous procedure which raised victims off the ground by their wrists tied behind their back, sometimes with the addition of sudden drops and other torments.

Pomponio Leto was not initially among the group arrested, as he was teaching in Venice at the time, but he soon joined them. He was arrested in Venice on an accusation of sodomy, because he had been writing erotic poetry to his male students; the Venetian authorities then extradited him to Rome, where the charges were altered. Like the others, he was accused of heresy.

They all now had a long ordeal, confined in their cells, uncertain how it would end. Their one consolation came from a sympathetic prison warden, Rodrigo Sánchez de Arévalo, who delivered their letters, wrote his own works of consolation for them, and allowed them to resume meeting one another. Pomponio wrote, thanking him: “Captivity is nothing amid the conversations of friends.” Rodrigo expressed amazement that, in such a dismal situation, they still managed not only to write but to do it with their usual beauties of style. But as we saw with Petrarch’s letters, humanists found nothing strange in expressing their sufferings in as elegant a way as possible. The cult of inarticulate or mystical silence—like the cult of ignorance—had no appeal for them. To exercise their eloquence was to affirm the values for which they were being persecuted.

Some of them were freed later that same year, but again Platina had the worst of it: he was kept inside until March 1469. None of the charges could be proved against any of them; nor did any evidence of real seditious activity ever subsequently emerge. A few years after these events, their situation became much better with another change of pope, to Sixtus IV. He allowed them to resume their jobs for the Curia. Platina would also later be taken on as the librarian of the Vatican Library. Meanwhile, he was able to resume his literary activities. He published a recipe book he had been working on for a while, with the very Epicurean title On Right Pleasure and Good Health; one of its dishes, grilled eel à l’orange, was so appealing that Leonardo da Vinci made it part of the fare in his fresco of the Last Supper. Platina also wrote a long history of all the popes, culminating in a scathing account of his former persecutor, Paul II.

The group eventually resumed its meetings and activities, though a little more discreetly than before. It was relaunched in 1477 as a lay Christian fraternity, which gave it a more respectable air. All the same, its members continued to meet sometimes in the ruins, for a discreet cavort.

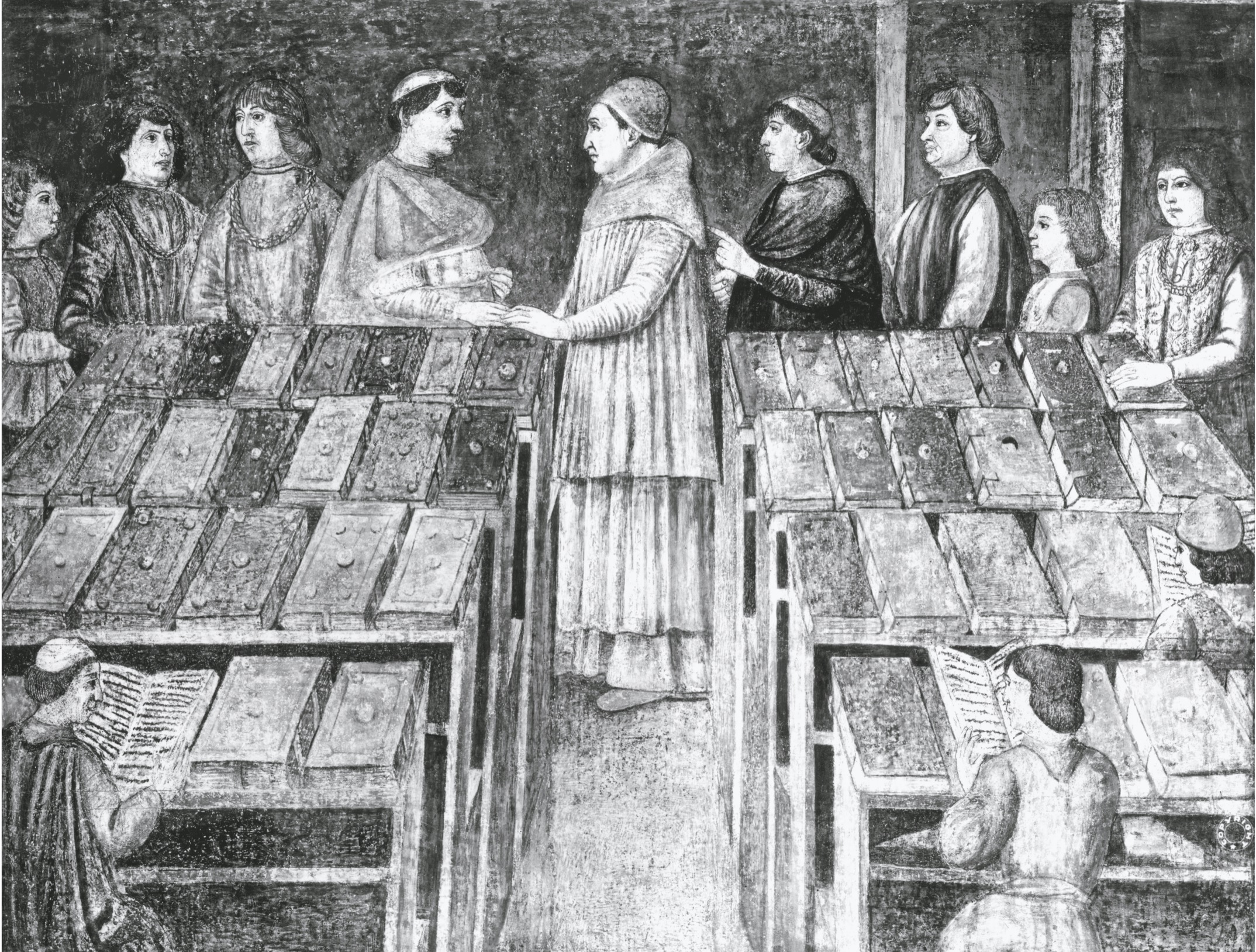

Platina and Pope Sixtus IV with the Vatican Library collection

While Roman humanists tended to remain bound, for better or worse, to the affairs of the church, those farther up the peninsula in Tuscany had a different set of obligations, and different kinds of masters to please. (Typically inclined to wandering, of course, some humanists had interludes or obligations in both places.) The Tuscan humanists were more likely to work either in purely private posts as tutors and secretaries or to have civic, diplomatic, or political appointments in the great Tuscan cities. These cities tended to present themselves as beacons of freedom, openness, and harmony. Their ideal image had been given visual form in frescoes by Ambrogio Lorenzetti in the late 1330s for the city of Siena, bringing out a contrast between good and bad government. One scene shows a city full of dancing merrymakers and happy traders, surrounded by fertile fields and well-fed peasants. This is the result of good government. Its opposite shows empty fields, desolate except for armies advancing on one another, and a grim and ruined city: bad government at work. To prefer good government to bad is to prefer order to chaos, peace to war, prosperity to starvation, and wisdom to stupidity.

That Florence was, out of all the Tuscan cities, the epitome of the “good” option was the argument of the city’s humanistic chancellor Leonardo Bruni. In his Praise of the City of Florence, written around 1403, he had characterized his community in terms of its freedom and its ability to harmonize sweetly with itself, like the strings of a harp. “There is nothing in it that is out of order, nothing that is ill proportioned, nothing that is out of tune, nothing that is uncertain.” Its citizens surpass others in every achievement. They are “industrious, generous, elegant, pleasant, affable, and above all, urbane.” And, as he wrote elsewhere, the humanistic studies—that is to say, “the best and most distinguished branches of learning and the most appropriate to humankind”—naturally flourish here:

Who can name any poet, of this or an earlier age, who was not a Florentine? Who but our citizens brought back to light and into practice this art of public speaking which had been completely lost? Who, if not our city, recognized the value of Latin letters, which had been lying abject, prostrate, and almost dead, and saw to it that they were resurrected and restored?

He reserves a special mention for the way “even the knowledge of Greek letters, which had become obsolete in Italy for more than seven hundred years, has been brought back by our city so that we may contemplate the great philosophers and admirable orators.”

Bruni himself had a lot to do with that, being a Greek expert and translator. He was especially interested in the historian Thucydides—who, among much other material, had provided a version of a famous speech given by the Athenian leader Pericles in 430 BCE. Amid an ongoing war with Sparta, Pericles addressed the citizens to commemorate fallen soldiers and praised Athens in terms that would be almost directly copied by Bruni in his praise of Florence. According to Thucydides, Pericles begins by asking, in effect, Why are we so much more wonderful than our enemies? Answer: Unlike the Spartans, obsessed with military drills and discipline, we have built Athens on a basis of freedom and harmony. Spartans shut themselves off, but we trade openly with the world. They brutalize their children to make them tough, but we educate ours for liberty. They are hierarchical, but in Athens everyone takes part freely and equally in the city’s affairs. What Pericles does not think to mention is that “everyone” here excludes women and slaves. His only mention of women comes in the final words, where he reminds any war widows in the audience that none of this applies to them, since a woman’s only virtue is not to be talked about by men, whether in praise or criticism.

Florence, too, had women and slaves who neither spoke in public nor were officially talked about. In general, the reality of both cities was not quite as described. Far from being harmonious, Athens experienced public disorder, plague, and uprisings, and it eventually lost that war with the Spartans. Florence, too, was a welter of dynastic conflicts, plots, regime changes, and general insecurity. Yet in both cases the humanistic ideal was central to their identities—and there is no question that Florence did become an energetic, artistic, intellectually active place through the fifteenth century, filled with larger-than-life characters and generally friendly to the activities of humanists.

The most eminent of these formed a circle associated with the Medici during the time when that family was effectively in control of the city. Several members of the circle, like their Roman counterparts, took up the Platonic name of “Academy,” and got together for meetings in a semi-formal group. They were particularly encouraged and supported in this by Lorenzo de’ Medici, “the Magnificent,” who was himself a humanistic poet, collector, and connoisseur, as well as a businessman, man of action, and political leader.

A central figure in the group was Marsilio Ficino, who translated Plato’s works using manuscripts in the Medici family’s collection, and also wrote his own study, Platonic Theology, advancing a philosophy that merged Christianity with Platonism. Plato was another of those “pagans” who had the bad luck to be born before Christ, but he did speak of the harmony of the cosmos and of an ideal “Good” in ways that some Christians had long seen as prefiguring their own theology. Although far from the first to explore this, Ficino brought a new style of scholarship to the task. Also, he was prepared to make bold claims about the role of humans in the universe. Highlighting human achievements in literature, creativity, scholarship, and political self-governance, he asked, “Who could deny that man possesses as it were almost the same genius as the Author of the heavens? And who could deny that man could somehow also make the heavens, could he only obtain the instruments, and the heavenly material . . . ?” That was quite a claim: if only we had the right tools and raw materials (admittedly, a tall order in both cases), we might rival God himself as Creator.

Similar speculations came from another member of the Academy circle in Florence: the dashing young aristocrat and book collector Giovanni Pico della Mirandola. He read widely, both within the Christian tradition and outside it, delving into esoteric and mystical ideas of all kinds. Having assembled material on such themes, he went to Rome in 1486 with the intention of organizing a giant conference, at which attendees could debate nine hundred theses or propositions supplied by himself. The event did not happen: the church did not like the sound of it and squelched it. Pico fled back to Florence for fear that he might be squelched, too. But the theses remained, and he had also written an introductory oration for them that would later acquire a resounding title: Oration on the Dignity of Man. For centuries, this would be held up as a kind of manifesto for the Florentine humanistic worldview, embodying a moment when the humanities research of the literary scholars became something grander: a philosophical vision of unfettered, universal humanity, proudly facing the cosmos on equal terms.

Recent Pico scholars have tried to tone down this view of him, arguing that he was really more interested in arcane mysticism, and reminding readers that the “dignity of man” part of the title was not his, anyway. This restoring of Pico’s Oration to its original context has been a valuable corrective to overexcitement. Still, there is no denying the emotional impact of its first few pages, where Pico, like Ficino, communicates an ambitious view of human capacities. He does it—as Protagoras had long before him—by telling a story about human origins.

In the beginning, goes Pico’s version, God created all beings. He set each kind on its own fixed shelf, as it were, allotting places according to whether they were plants, animals, or angelic creatures. But he also made humans, and for them he imposed no predefined level. God told Adam: instead of giving you a single place or nature, I will give you the seeds of any way of being. It is up to you to choose which kinds to cultivate. If you choose your lower seeds, you will become as an animal, or even a plant. If you choose the higher ones, you may rise to the height of the angels. And if you choose intermediate ones, you will fulfill your own variable, human nature. Thus, says God: “We have made you neither of heaven nor of earth, neither mortal nor immortal, so that you may, as the free and extraordinary shaper of yourself, fashion yourself in whatever form you prefer.” Pico comments, “Who will not wonder at this chameleon of ours?” And: “Who will admire any other being more?”

This passage was by far the most memorable in Pico’s work, and no wonder: this shimmering, shapeshifting chameleon presents a thrilling image of ourselves. It seems considerably more exciting than the work of the patient literary scholars, copying manuscripts and fussing over their Ciceronian Latin. Yet in reality Pico was not that remote from them. He, too, was trying to produce an erudite, cross-disciplinary work of scholarship, mixing materials from a wealth of philosophical and theological traditions. Just as humans in general can be anything they choose, he implies, so should scholars be able to take the wisdom and knowledge they need from any source, whether Christian or not. One can see why the church thought his conference in Rome would be too much to tolerate.

Meanwhile, one also has to ask: Could such a multisided, self-determining, free, harmonious marvel ever actually exist? How many human chameleons were walking around Florence?

Certainly, if you hoped to find one, Florence was a good place to look. Candidates for models of all-capable humanity who might often be found there included Leonardo da Vinci, the versatile artistic and scientific genius, and the architect Leon Battista Alberti. Those were in fact the two names chosen by the nineteenth-century historian Jacob Burckhardt when he was looking for exemplars of what he considered the era’s distinctive figure: the uomo universale, or “universal man,” who could take on any form and achieve almost anything in a fluid, constantly changing society.

The choice of Leonardo makes some sense, given the astonishing range of his interests. (We will come back to him in a moment.) Leon Battista Alberti seems an apt choice, too, especially if we read a glowing contemporary account of his achievements written by an anonymous author who—we are now fairly certain—was none other than Alberti himself. It portrays him, not without justification, as a man of innumerable facets, capable in every field of life, excelling in every quality except modesty.

He did have a lot to be immodest about. Besides designing buildings and producing pictures, he wrote important treatises on the arts of painting, building, and sculpture. He was an expert surveyor and devised new techniques to produce a study of Rome’s ruins. He wrote Latin poems, a theatrical comedy about Greek gods, and a book titled Mathematical Games. Each of his fields of expertise enhanced the others, as when he used his mathematical talents to work out rules for creating the illusion of perspective in visual art.

Those achievements are well documented, but the biography goes further. Alberti wrestled, he sang, he pole-vaulted, he climbed mountains. In youth, he was strong enough to throw an apple over the top of a church and to jump over a man’s back from a standing start. He was so resistant to pain that, when he wounded his foot at the age of fifteen, he could calmly help a surgeon to stitch it closed.

He cultivated subtler abilities, too. By going bareheaded on horseback (an unusual thing to do), he trained himself to endure chills on his head, even in the fierce winds of winter. Applying the same principle to the cold winds of social life, he “deliberately exposed himself to shameless impudence just to teach himself patience.” He loved talking to everyone he could find, seeking new knowledge. He would invite friends over so that they could talk about literature and philosophy, “and to these friends he would also dictate little works while he painted their portrait or made a wax model of one of them.” In every situation, he sought to behave virtuously; “he wanted everything in his life, every gesture and every word, to be, as well as to seem to be, the expression of one who merits the good will of good men.” At the same time, he valued sprezzatura, “adding art to art to make the result seem free of artifice,” especially when it came to three important activities: “how one walks in the street, how one rides, and how one speaks; in these things one should make every effort to be intensely pleasing to all.” Throughout all of this, he “kept a cheerful manner and even, insofar as dignity permitted, an air of gaiety.”

Alberti was thus the very model of the splendid, accomplished, free human being in the full sunlight of his days. True, he was exceptionally able. But what is being conjured up here is more than that; it is an ideal figure of the human in general. All the qualities highlighted are those of humanitas: intellectual and artistic excellence, moral virtue and fortitude, sociability, good speaking, sprezzatura, being courteously “pleasing to all.” Along with this comes his excellent physical condition: the mental abilities were reflected in his physical proportions. Reading his description, one pictures another figure of the time: that of “Vitruvian Man.”

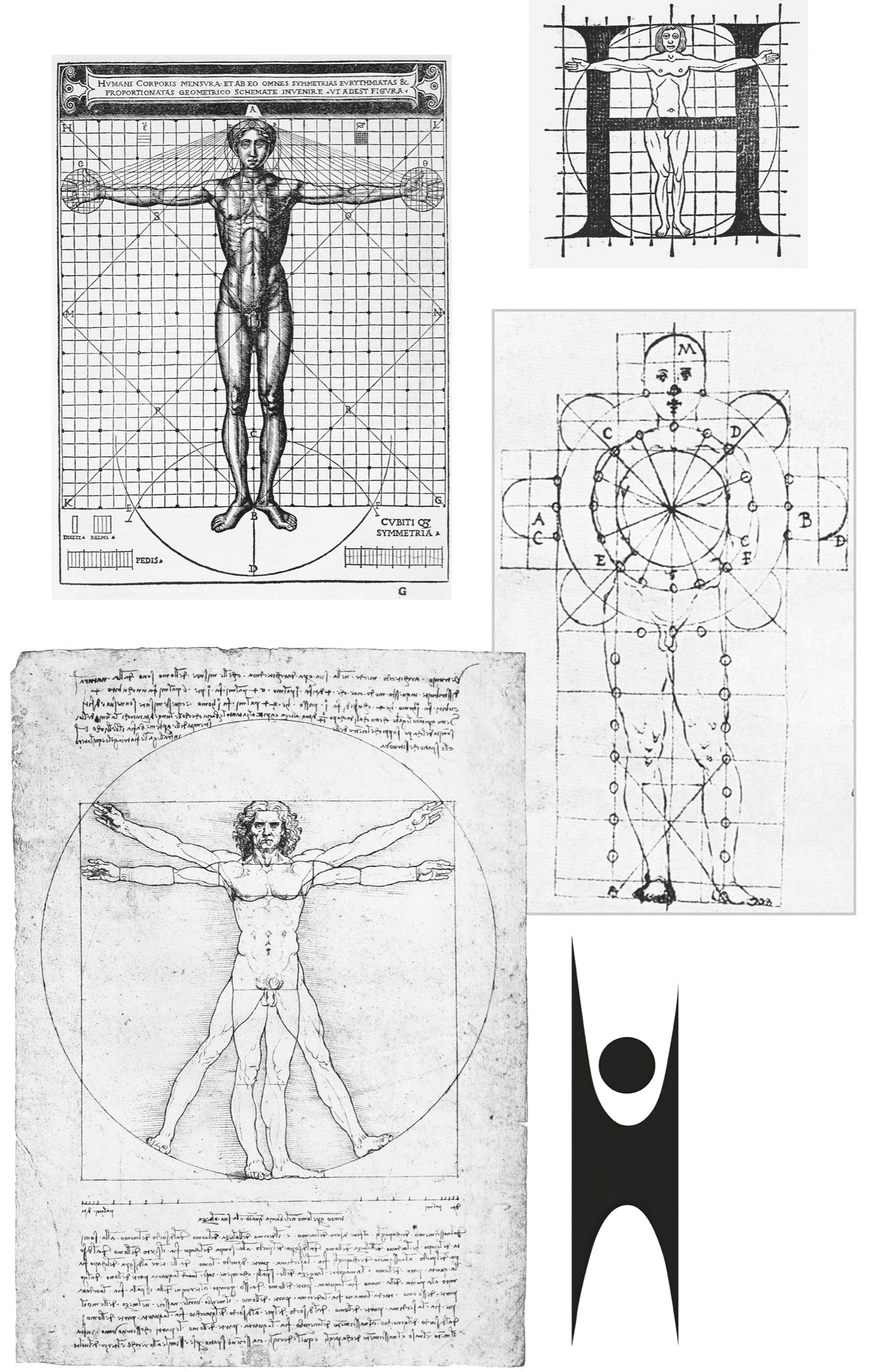

Vitruvian Man was a perfectly proportioned, steady-gazing, well-formed male figure, whose origin is purely mathematical. He illustrates the ratios of distance that were supposed to exist between parts of the human body: the chin to the roots of the hair, the wrist to the tip of the middle finger, the chest to the crown of the head, and so on. Calculating these ratios in the first century BCE, Vitruvius was interested not so much in anatomical design as in architecture: these proportions of the male body seemed to him the best basis for the shape of a temple. Thus, the human being—as Protagoras would have said—should literally be taken as the measure, or criterion. Vitruvius gave the method for deriving the data. If a man lies on his back with hands and feet spread, and you draw a circle with his navel as the center, the circumference will touch his fingers and toes. You can also create a square based on the span of his arms and the length of his body, when he brings his feet together.

Artists of the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries did their best to make this Vitruvian ideal come true. Even designers of printing fonts modeled their letters on the Vitruvian body. Michelangelo Buonarroti followed the temple theme by designing a facade for the San Lorenzo church in Florence based on such dimensions—although he never built it, because he could not source the marble he wanted.

Most celebrated was the drawing made around 1490 by Leonardo da Vinci, showing a man in the two positions simultaneously, along with his measures in delicate box shapes. The man is positioned inside a circle centering on his navel, as well as a square. His expression is frowning but serene; he has a fine head of hair, and turns one foot sideways to show how its dimensions fit with the whole. He is perfect—apart from having too many arms and legs.

Leonardo’s original drawing sits well guarded in the Gallerie dell’Accademia in Venice, but the disembodied image has traversed a huge sweep of history and geography, representing human confidence, beauty, harmony, and strength. It has become an instant icon for the idea of the “Renaissance,” and of “universal man”; a visual companion to Pico’s dignified chameleon. Even the international symbol for the modern humanist movement echoes it: the “Happy Human” image, designed by Dennis Barrington in 1965, shows a human shape with arms flung up in a similar way, full of confidence, openness, and well-being. (Interestingly, Humanists UK has now moved away from this toward a more fluid symbol resembling a dancing piece of string—chosen because it is a figure following its own motion instead of standing before us to be measured. You can see this symbol at the end of the last chapter of this book.)

In fact, what distinguishes the Leonardo image from other Vitruvian ones is that it does not submit to symmetrical measurements; its shapes are not concentric. Leonardo achieved the figure’s visual beauty and plausibility by displacing the square downward. The circle centers on the navel, but the square centers somewhere around the base of the man’s penis. Also, the upper tips of the square poke through the circle’s radius. The proportions had to be tweaked, because even “ideal” humans are not a precise set of boxes and circles. Many correspondences do exist: the finger-to-finger span of a broad-shouldered man is likely to be more or less the same as his height. But without adjustment, a real Vitruvian man would look mighty weird, as is clear from some other examples, such as the one in a 1521 Italian translation of Vitruvius illustrated by Cesare Cesariano.

The message here is that real human beings, even those who match the dominant template of muscular masculinity, are characterized by something less than perfect harmony. They are subtly off-center. An ideal, harmonious human cannot be found any more than an ideal, harmonious city can (or even a harmonious chameleon). Immanuel Kant was surely closer to the truth when he wrote, three centuries later: “Out of such crooked wood as the human being is made, nothing entirely straight can be fabricated.”

Another young man, from farther north in Italy, had also started his intellectual career by studying Platonic philosophy, along with medicine: Girolamo Savonarola. Born in Ferrara in 1452 to a family of physicians, he was all set to follow the same profession. As part of his studies, he wrote poetry in the Petrarchan vein and essays on Plato’s dialogues. But then he heard the voice of God, quit medical school, and tore up his work on Plato.

What God said to him, in effect, was: Destroy these vanities! This appetite for knowledge, this poetry, this reading of pagan philosophers—it is all so much futility, egotism, and distraction from piety, and it must be rooted out. No earthly matter is as important as preparing for death and heaven. While in this world, as Savonarola said later, we should be “like the courier who arrives at the inn and, without removing his spurs or anything, eats a mouthful, and . . . says, ‘Up, up quickly, let’s get going!’ ”

“Up” he did. Savonarola left his family without a word and walked the fifty kilometers or so from Ferrara to Bologna. There he presented himself at the city’s Dominican monastery. They took him in, and afterward he wrote to his father to tell him what he had done. To explain his reasons, he referred his father to a tract he had written on the need for contemptuous rejection of all worldly things.

Having taken his monastic vows, Savonarola found that he had a rather worldly talent, after all: he was brilliant at inspiring people with his preaching. He tried to develop this skill further by seeking lessons in humanistic eloquence and oratory—arts of pagan origin, but ones that promised to be useful. The teacher he approached for lessons, Giovanni Garzoni, gave him a rude brush-off, which would not have improved Savonarola’s attitude toward the whole humanist enterprise. He started whipping himself regularly and acquired a haunted look, with frowning brow and piercing eyes, which went well with his huge nose and gave extra impact to his words. In 1482, he moved to the Convent of San Marco in Florence, where he taught novices; then he spent some years on the road preaching in other cities before being called back to Florence by no less a personage than Lorenzo de’ Medici.

Lorenzo at that time was ill with an arthritic condition, perhaps ankylosing spondylitis; he would soon die. Being in extremis might help explain his seeking someone as extreme as Savonarola to guide him spiritually through to the end. Yet many of the other humanists in his circle became fascinated by Savonarola too, including both Pico and Ficino. They were drawn to his talk of cleansing Christianity of the corruption that had crept into it; as we saw with Valla, humanists were often interested in clearing out corruption, of texts as well as of morals. There was also Savonarola’s charismatic intensity, which seemed to hypnotize everyone; the humanists fell for it without thinking that they, and everything they held dear, might easily join his other targets. The possibility became clearer only when he proposed making more funds available to the poor—by removing such funds from the university. Not all the humanists were connected with that institution, but it represented principles of learning and scholarship generally. One thinks of the way some twentieth-century Western intellectuals fell in love with totalitarian communism, never considering what such a regime would be likely to do to them.

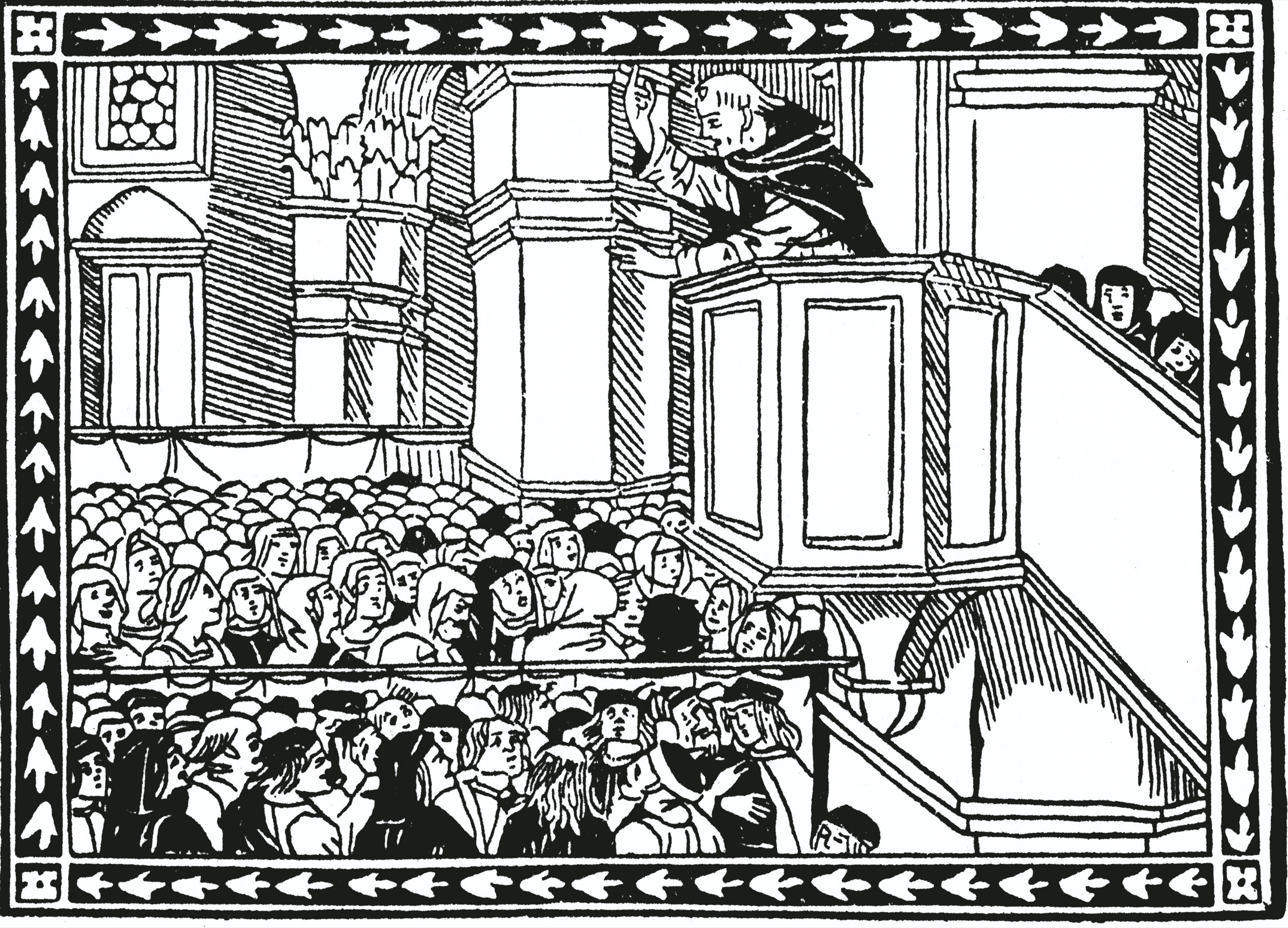

Savonarola’s appeal to the poor was easier to understand, with his condemnation of elitism and of the greed of clergymen. He built up a huge audience for his sermons at San Marco, and at the Florence cathedral—where ten thousand people at a time could hear him under the beautiful cupola designed earlier that century by Filippo Brunelleschi.

As he acquired more followers, they took to processing through the streets chanting and lamenting, and became known as his piagnoni: big weepers, or wailers. Gangs of children, fanciulli, were organized to march behind banners and collect money. They assaulted passersby, especially women considered immodestly dressed, and went from house to house demanding “vanities.” As a witness wrote, describing the scenes of February 16, 1496:

So great was the grace poured out on their lips that all were moved to tears, and even those who were their enemies would give them everything, weeping, men as well as women, diligently searching out everything such as cards, tables, chessboards, harps, lutes, citterns, cymbals, bagpipes, dulcimers, wigs, veils (which at the time were very lascivious ornaments for women’s heads), disgraceful and lascivious paintings and sculptures, mirrors, powder and other cosmetics and lascivious perfumes, hats, masks, poetry books in the vernacular as well as Latin, and every other disgraceful reading material, and books of music. These children inspired fear in any place where they were seen, and when they came down one street, the wicked fled down another.

In following years, the processions culminated in bonfires. A huge eight-sided wooden pyramid would be built in advance, stocked with logs inside for fuel; then the vanities collected by children could be balanced or hung on tiers on each side. There they went—mirrors, perfume bottles, paintings, musical instruments—all arranged “in a varied and distinctive way in order to appear delectable to the eye,” as one witness said. (The burners of vanities were not lacking in aesthetic sense themselves.)

Savonarola was not the first to devise such a spectacle. Fra Bernardino da Siena and Fra Bernardino da Feltre had burned books and other items a decade earlier in Florence, the latter while declaiming catchy phrases such as “Each time we read the ribald Ovid we crucify Christ!” Savonarola’s bonfires featured modern authors together with the classical ones. And if the books were beautifully written and bound, so much the better: among the items in his 1498 fire was a Petrarch collection “adorned with illustrations in gold and silver.”

He would also have liked to do the same thing to certain kinds of people. He called for hideous penalties for “sodomites”—homosexuality being officially illegal in Florence at the time, but seldom actually punished. Instead, he thought the law should be administered “without pity, so that such persons are stoned and burned.” He did succeed in persuading the city’s legislators to some extent: mild incidents previously punishable by a fine were now deemed to require an escalating series of atrocities for repeat offenders: the pillory, then branding, and finally burning alive. When officials proved sluggish about imposing such horrors (the fines had been more lucrative, after all), Savonarola raged: “I’d like to see you build a nice fire of these sodomites in the piazza, two or three, male and female, because there are also women who practice that damnable vice.” They must be made “a sacrifice to God.”

In the end, Savonarola himself suffered the fate he was so keen to see others suffer. He fell foul of the church, not directly for the bonfires or processions but because he claimed to be led by visions, particularly one in which the Virgin Mary told him that Florentines must repent of their ways. Personal visions, especially when combined with anticlericalism, amounted to a challenge to the church’s right to mediate all religious experience. The pope called Savonarola to Rome to explain himself in 1497 and, when he refused to go, excommunicated him. The Florentine authorities did not want to fight with the Roman ones, so they arrested Savonarola and tortured him with the strappado until he signed a confession saying that he had only pretended to have real visions. After a series of further inquisitions and trials, he was sentenced to death. On May 23, 1498, he was hanged with two other men, then burned on the scaffold. The ashes were taken away on wagons and thrown into the river, so that no relics would remain. Even La Piagnona, the bell at San Marco that had called his followers to his sermons, was put on a cart and whipped through the streets, then exiled from the city. But Savonarola did live on in human memories, which were harder to obliterate. The city’s two greatest historians of the next generation were both affected by their experiences of this time: one, Francesco Guicciardini, was the son of a piagnone and may have been a fanciullo himself. The other, Niccolò Machiavelli, had heard Savonarola preach. Machiavelli tried to work out why someone so able to tap into popular feeling had ended so badly, and concluded that the main problem was that Savonarola had failed to enforce continuation of that feeling by keeping a private army.

One might feel a certain sympathy for Savonarola, precisely because his story did end so ignominiously, and because of his salutary critique of church corruption and his championing of the interests of the poor. He gave eloquent voice to real grievances. Like Valla, he was unafraid to challenge a huge institution whose claim to authority rested on dubious foundations. And to be really generous to him: he wanted to help Florentines by pulling them back from the risk of damnation after death.

But he was a man of violence, whose desire to kill sodomites was murderous, and who used his oratorical skills to raise a storm of angry self-righteousness in his listeners. He sent out his followers to gather everything that showed a love of the human body or mind, everything that was refulgent and decorative and exquisitely wrought, every game that was fun to play, every book that was delightful to read, every flirtatious trinket, every symbol of worldly joy. He assembled these things with the dedication of the great humanist collectors—and burned them. All those productions of human skill and beauty were converted to carbon dioxide and ashen sludge.

As for his overall philosophy, Thomas Paine would sum it up centuries later when he wrote that some people seem to think it an expression of humility to call “the fertile earth a dunghill, and all the blessings of life by the thankless name of vanities.” Instead, in Paine’s opinion, it looks more like ingratitude.

Violence against art and people alike swept through other parts of the Italian peninsula at the end of that century, with invasions by French forces, who seized the territory of Naples, so ably defended by Valla and his philology, and took it over without a battle in 1495. Their advance through the rest of the peninsula left much trauma in its wake. The worst shock for Rome came a few decades later, in 1527, when unpaid, mutinous former soldiers of the emperor Charles V broke through its defenses and sacked the city. Many of the soldiers were followers of Martin Luther, leader of the Protestant Reformation: a rather more successful rebel against church authority than Savonarola could ever have been. Having been deprived of their own pay, they grabbed any money or treasures they could find, and smashed things they could not use. They moved through the streets attacking locals unfortunate enough to meet them, and hauled out relics from churches. Among graffiti on the walls inside the Vatican, one can still see the single word “Luther” scratched into the plaster under a Raphael fresco.

Many books were destroyed in the city, too, both from the Vatican Library and from private collections. After the humanist Jacopo Sadoleto’s library was wrecked, he wrote to Erasmus, “It is unbelievable, all the tragedy and loss that the ruin of this city has brought upon mankind. Despite its vices, it was virtue that occupied the greater place. A haven of humanity, hospitality, and wisdom is what Rome has always been.”

Among others who lost a personal library was Paolo Giovio, physician to Pope Clement VII. He helped Clement to escape, lending him his own cloak to cover the distinctive white papal gown as they scurried along a secret passageway out of the Vatican to the Castel Sant’Angelo: the very place where the church had tortured Platina and the other Academy members six decades earlier.

Later, Giovio left the city and spent some time getting over it all on the island of Ischia, where Vittoria Colonna hosted a retreat for her friends, with the old humanist entertainments to soothe them. They spent their days telling stories, like those refugee nobles of The Decameron again, and elegantly debating topics, just as Castiglione’s courtiers did in Urbino. Giovio would publish their discussions in a work called Notable Men and Women of Our Time.

In the real world, much had changed, for humanists and for others. Rome’s sufferings in 1527 shocked all of Catholic Europe. It was one thing for a humanist to mock and goad Roman authority, but this was food for thought: If even this ancient and august city could be attacked in such a way, how could anyone feel safe anywhere? The rest of the 1500s bore out such fears, as religious war and chaos raged through Europe.

Out of such experiences, as well as other challenges to Europeans’ understanding of life—notably their encounter with a “new” world across the Atlantic and an explosion in the amount of printed information available—sixteenth-century humanists would become ever less naively adoring of the past and ever more interested in social complexity, human fallibility, and the effects of large-scale events on individual lives. The spirit of questioning, pioneered by Valla and other humanistic scholars who refused to limit themselves to approved sources, gained further ground. The interest in the changeable human chameleon shown by a Pico or Ficino remained but became less theological and more pragmatic. For example, the historians Niccolò Machiavelli and Francesco Guicciardini developed a tough, investigative attitude; they reflected on the causes of historical changes and on the reasons why people behave as they do.

A similar interest in human complexity brought a revival of another human-centered genre: biography, with its questioning of causes and consequences in individual lives. Paolo Giovio was among the new biographers, though his work was gentler than the historians’. He returned north to his home region near Lake Como and built himself a villa, as you do when you want to get away from mayhem and discord. He based the design on descriptions of ancient villas once owned in the area by the local uncle-and-nephew team, Pliny the Elder and Pliny the Younger. The latter had even written of having a bedroom window so close to the lake that he could fish from it: a beautiful thought. Giovio did not manage that, but he did turn his villa into an even more extraordinary window on life. He used it to house a museum, open to visitors and filled with portraits of people who he hoped would inspire viewers to emulation. He also published a book of these pictures, writing a potted text to go with each woodcut. The original villa collection does not survive, but copies of the portraits were painted for Cosimo I de’ Medici by Cristofano dell’Altissimo. These works now run high on the walls down the whole First (or East) Corridor of Florence’s Uffizi Galleries, occupying such an honored position that many people, hurrying toward their Botticellis, don’t quite notice that they are there.

One evening at a dinner party, Giovio mentioned that he would like to devote a volume to the modern artists of the day. Sitting near him was the painter Giorgio Vasari, who knew absolutely everyone in the art world. Splendid idea, he said. But why not bring in a real expert to advise on it? Others at the table chimed in: You should do it, Giorgio!

So he did, and Vasari’s Lives of the Great Painters, Sculptors, and Architects was published in 1550. It was a treasure house of gossip and of reputation-making praise, as well as an assessment of techniques written by a working professional. (Vasari’s work included gigantic, somewhat blowsy frescoes, but he also did smaller paintings, one of which is a chronologically fanciful group portrait of six Tuscan poets, dominated at the center by Dante and Petrarch with Boccaccio peeking between their shoulders.) In the Lives, Vasari did more than anyone else to advance the idea that a “renaissance,” or “rebirth,” had taken place since the times of those poets: thus, he suggested the fulfillment of Petrarch’s dream, albeit in the visual rather than literary arts. But Vasari saw a rebirth in the world of scholarship, too: he compared his own project to the achievements of the new, subtle historians “who realize that history is truly the mirror of human life—not merely the dry narration of events . . . but a means of pointing out the judgments, counsels, decisions, and plans of human beings, as well as the reason for their successful or unsuccessful actions; this is the true spirit of history.”

The actions of humans, the difficulty of making good judgments, the uncertainty of all things—these themes would continue to fascinate sixteenth-century writers. They would have to face the religious split in western Europe, and the revelation that the world was much bigger and more diverse than the ancients had expected. This would bring some of them to a subtle understanding of uncertainty and complexity. A few would also realize that nothing was more complex or self-divided than an individual human being.

We shall see where these ideas took them. But first, let’s talk about bodies.