4.

Marvelous Network

Mostly 1492–1559

Books and bodies—Girolamo Fracastoro and his beautiful poem on a terrible disease—Niccolò Leoniceno: bad texts kill people—botanists and anatomists—death delights in helping life—Andreas Vesalius and his humanistic masterpiece—although he did overlook something—all is in flux.

Just as a mighty city like Rome could be invaded and turned into a scarred, depleted mess, so could a human being be invaded and ruined by disease. This was the starting point for a poetic journey through a not very glamorous topic: Syphilis, or The French Disease, published by the humanist physician Girolamo Fracastoro in 1530, though written earlier and influenced by the general disasters suffered throughout the peninsula. He addresses Italy: Look, he says, how you were once so happy and peaceful—loved by the gods, fertile, wealthy—and yet now your land has been plundered, your holy sites defiled, and your relics stolen. This calls to mind the likely fate of a good-looking young man if syphilis were to attack his face and body, and wreck his mind and spirit.

As he says all this, Fracastoro’s poem is achieving the opposite: turning an ugly subject into beautiful Virgilian verse. Like Boccaccio in his plague prelude to The Decameron, Fracastoro piles on the miseries at the beginning, but soon goes on to the pleasures of storytelling. He gives us magical rivers of mercury flowing underground, beaches sparkling with gold dust, air filled with brightly colored birds, and the tribulations of a naive shepherd—all doubling as ways of presenting possible syphilis cures. Applying the best medical expertise of the era, he explores a series of approaches culminating in the medicament he thinks most likely to succeed: the bark of guaiacum, or guaiac wood, which comes from a flowering shrub found in the New World.

What I love about Fracastoro’s poem is its blend, characteristic of its time, of genuine inquiry into the world with literary elegance reveled in for its own sake. It resembles Pietro Bembo’s dialogue De Aetna—and lo, Bembo is its dedicatee. There are two good English translations through which non-Latin readers can appreciate Fracastoro’s imagery. I have a fondness for the 1984 one by Geoffrey Eatough, which, although in prose, really goes to town with Fracastoro’s voluptuous love of words. Here is dietary advice for the syphilitic:

Shun tender chitterlings, the belly of a pig curving with fat, and, alas, the chine of pig; don’t feed on boar’s loin, however often you have slain boars out hunting. Moreover, don’t let cucumber, hard to digest, nor truffles entice you, nor satisfy your hunger with artichokes or lecherous yonions.

And here is his final paean to guaiacum:

Hail great tree sown from a sacred seed by the hand of the Gods, with beautiful tresses, esteemed for your new virtues: hope of mankind, pride and new glory from a foreign world; most happy tree . . . you will also be sung under our heavens, wherever through our song the Muses can make you travel by the lips of men.

Besides giving rein to his literary skills, Fracastoro was a working physician who genuinely wanted to help people recover. Sadly, guaiacum, which induces sweating, is of little use against syphilis. (It does have another application today, however: by reacting chemically with hemoglobin, it can flag the presence of blood in urine or feces.) But Fracastoro could draw only on the materials of his time. Like any researcher or practitioner today, he studied the literature, tried to excel in his field, and worked toward the goal of all medicine: reducing suffering and improving human lives. He just did it in hexameters.

Mitigating the suffering of one’s fellows is a humanistic goal in the broadest sense, and in general the practice of medicine straddles the worlds of science and of humanistic study. It uses quantifiable research (far more so now than in Fracastoro’s day) but also patients’ personal accounts of what they feel; a working doctor must know how to listen and talk well with those patients. Medicine deals in observable and experienced phenomena. But it also relies on books: knowledge is passed from practitioner to practitioner through education and the sharing of professional experience. Like other sciences, it explicitly deploys the humanities, especially history, so as to reflect on its own past and to refine its approach. Far more than other sciences, it draws on contemporary prevailing ideas of who and what we are as humans, and generally as living beings. In return, medicine helps to change what we are, as we become (hopefully) more knowledgeable about our own systems and ultimately able to meddle a little with our own basic chemistry and processes.

This is why, in his 1979 book Humanism and the Physician, Edmund D. Pellegrino wrote that medicine “stands at the confluence of all the humanities.” And the nineteenth-century scientist and educationalist T. H. Huxley (who will reappear in a later chapter) recommended the study of human physiology as the best foundation for education of any kind:

There is no side of the intellect which it does not call into play, no region of human knowledge into which either its roots, or its branches, do not extend; like the Atlantic between the Old and the New Worlds, its waves wash the shores of the two worlds of matter and of ymind.

Humanism and medicine mingle: this chapter is a case study in how humanistic skills intertwined themselves with early modern attempts at the study of actual people. It could be read as an interlude, but it is also a turning point in our story, as European humanists become less subservient to the ancients, look more closely at the real world, and inquire into physical and mental life, asking, What sort of creatures are we, and what does it mean to have a human body?

I said that the aim of medicine is to reduce suffering, but unfortunately for much of history it failed to achieve this, and even inadvertently made things worse. Some practices were needlessly invasive, as with cutting to release blood in the belief that it had become toxic or needed reducing. Ingesting substances such as dung or “mummy” (fragments of human remains, sometimes blended with bitumen) was thought to be good for you precisely because it was disgusting. The luckiest patients received treatments that were merely useless instead of life-threatening. Ideas of regimen were also variable: shunning chitterlings might be helpful at times, but Petrarch was advised by doctors to avoid all vegetables, fruit, and fresh water—not considered healthy advice for most situations today. No wonder Petrarch had nothing but invective for doctors, even though he counted several among his best friends. He reserved special scorn for those who showed off their humanistic learning most: “All are learned and courteous, able to converse extraordinarily well, to argue vigorously, to make quite powerful and sweet-sounding speeches, but in the long run capable of killing quite artistically.”

Some thirty years after these remarks by Petrarch, Geoffrey Chaucer included a physician in his Canterbury Tales who thought gold was the best remedy for the plague—if administered to himself in the form of a coin. “Gold in phisik is a cordial. / Therfore he lovede gold in special.” Chaucer prefaces that remark by listing the authorities the physician has studied: Hippocrates, Dioscorides, Galen, Rhazes, Avicenna. This amounts to a good summary of the canon of early medicine. The first two were Greek pioneers; the last two were the great Persian scholars al-Rāzī and Ibn Sīna. The most influential authority on the list was the middle one: Galen, physician to the emperor of Rome in the second century CE and writer on almost every area of medical practice, ranging from anatomy and pathology to diet and psychology.

All these authors were intelligent, judicious, and full of good advice, but they all had failings. Also, as happened in other fields, their texts had become fragmentary and corrupted by repeated copying. With Greek having been unreadable to most western Europeans for so many centuries, the Greek authors tended to come into Latin via Arabic, doubling the potential for mistranslation. In the 1400s and 1500s, new generations of humanists applied their philological skills to translating the authors afresh, using the most accurate sources they could find. They promoted their work with the usual jailbreak images: one physician rejoiced in his preface at how, thanks to himself, Hippocrates and Galen had both been “rescued from darkness perpetual and silent night.”

More than with other subject areas, medical humanists had an urgent sense of the need for such work. No one is likely to die because a line of Homer has been misread. If a fake legal or political document is allowed to pass, as with the Donation of Constantine, it can have major consequences but is not directly lethal. But when a medical text is garbled, people can die.

The first to make this point forcefully was Niccolò Leoniceno, in his On the Errors of Pliny and Other Medical Writers, first published in 1492. Pliny the Elder’s Natural History was a first-century compilation of secondhand information about herbs and health, among other topics, and it was often relied upon too much, even though Pliny himself made no claims to quality control. Humanists loved him just as much as their medieval predecessors did. Petrarch filled his Pliny manuscript with notes, and a copy now in Oxford’s Bodleian Library glories in notes by Coluccio Salutati, Niccolò Niccoli, and Bartolomeo Platina. For humanists, Pliny’s appetite for miscellaneous information was congenial, and if they noticed errors, they politely blamed them on copyists, not on him. Leoniceno, however, squarely blamed the author. He said he could fill a whole book with Pliny’s blunders, especially when it came to identifying medicinal plants. The question is not just one of words, he wrote, but of things. And people’s health and lives depend on getting medical language right.

Like Lorenzo Valla before him, Leoniceno was not afraid to attack an ancient authority when he felt the truth was important. Also like Valla, he preferred to lead readers away from bad versions and back to earlier, more authentic sources. In his case, that could include looking at the actual plants. He ended his treatise:

Why did nature grant us eyes and other senses, if not that we might see and investigate the truth with our own resources? We should not deprive ourselves and, following always in others’ steps, notice nothing for ourselves: this would be to see with others’ eyes, hear with others’ ears, smell with others’ noses, understand with others’ minds, and decree that we are nothing more than stones, if we commit everything to the judgment of others and decide on nothing ourselves.

Even with this defense of what now sounds like a modern empirical approach, Leoniceno was still a humanist. He expresses himself with the usual gestures of elegance; he sees no conflict between being a good philologist and being a good investigator of the real world—in fact, they go well together. After all, Lorenzo Valla, too, had looked into questions of real-life plausibility and veracity, as well as purely linguistic considerations. What neither of them believed in was excessive veneration of authorities just because they were authorities.

Leoniceno collected manuscripts himself, and he was that other very humanist thing: a courtier, working in the ambit of rich patrons. He developed his career while working as physician to the Este dukes in Ferrara, the intellectually lively court now presided over by Alfonso I and his wife, Lucrezia Borgia—who was a great friend to humanists. Leoniceno dedicated his little treatise On the Dipsas and Various Other Snakes to Lucrezia, perhaps very delicately implying that she had a special interest in the venom of the species described in ancient literature as dipsas. (The snakes now called that are not venomous at all.) He also published a work on syphilis in 1497, thirty-three years before Fracastoro, no doubt another subject that had a certain relevance at court. Like good popular science writers today, Leoniceno could communicate well with a non-expert audience while also pursuing specialist work. His combined editing and scientific career was crowned when, at the age of eighty-six, he produced his own edition of selected Galen works with a commentary, published by the French humanist printer Henri Estienne in 1514.

By that time, checking books against plants was becoming easier, thanks to the creation of botanical gardens in courts and university towns around Italy. These gardens positively bloomed with humanists. In Ferrara, the court physician Antonio Musa Brasavola simultaneously gathered plants from the surrounding countryside and multilingual synonyms for their names from books. In Bologna, Ulisse Aldrovandi assembled huge volumes of natural history based on his personal museum of specimens and also wrote commentaries on ancient texts.

While the philologist-botanists were comparing plants and words, other critical thinkers were applying a similar principle elsewhere. They began comparing anatomical books to the human bodies those books claimed to describe.

It had long been recognized that looking inside bodies was a good idea, when possible. Galen was all in favor. But in practice it was hard to achieve, because religious and political authorities in the early Roman, Christian, and Islamic worlds alike outlawed it. Galen had to use non-human species such as sheep or the Barbary macaque for his dissections. Later, a long shadow was cast by Augustine’s view in the early fifth century that anatomical dissection was wrong because it ignored the holistic harmony of the living body—never mind the fact that better anatomical knowledge might help stop that harmonious living body from dropping dead. As the nineteenth-century pro-anatomy campaigner Thomas Southwood Smith would later say, “The question is, whether the surgeon shall be allowed to gain knowledge by operating on the bodies of the dead, or driven to obtain it by practising on the bodies of the living.”

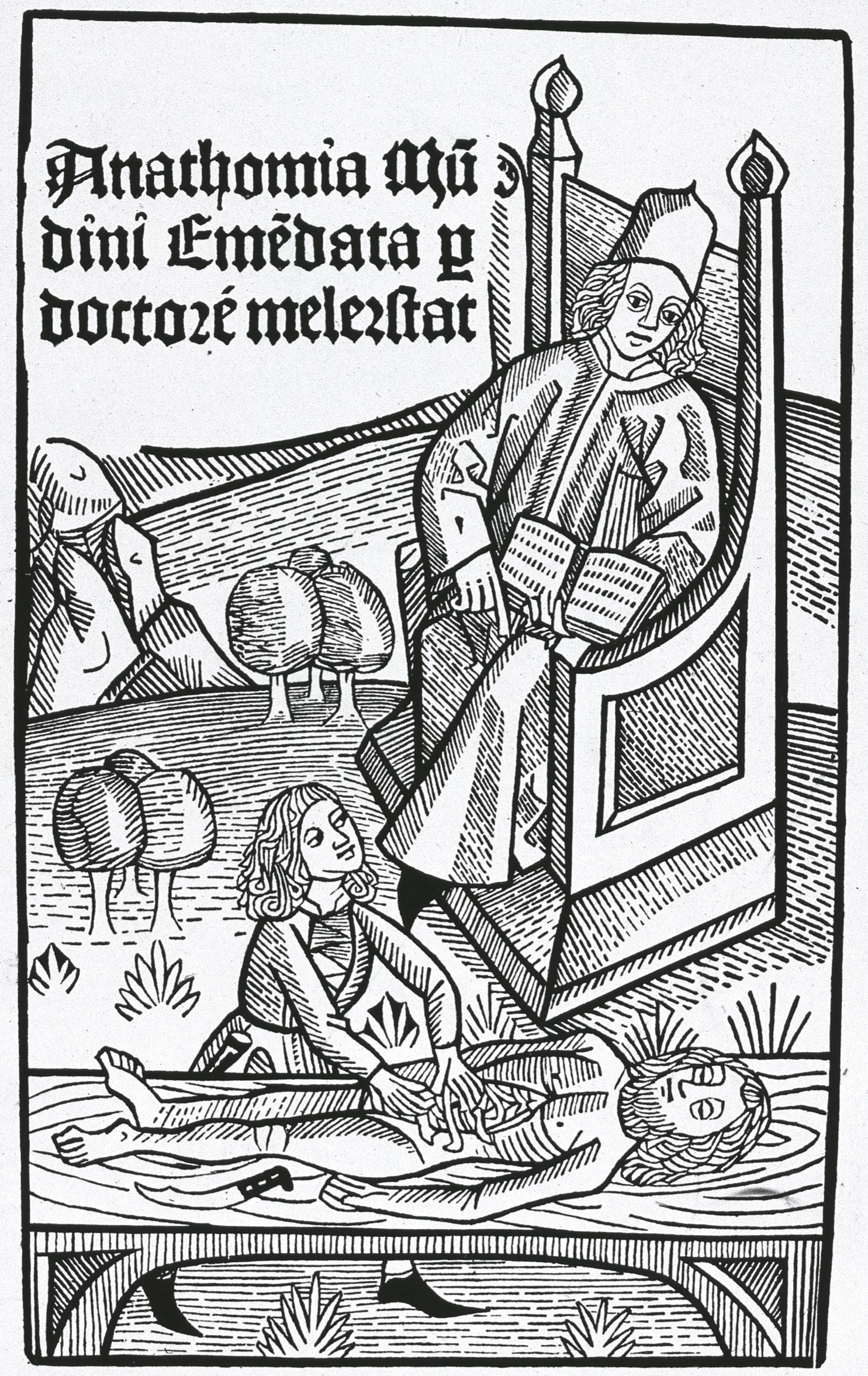

By the late thirteenth century, some had begun to defy the dissecting ban, notably in Bologna, where Mondino dei Liuzzi used corpses of executed criminals to demonstrate anatomy to students. Others followed him. Eventually, the rules were relaxed and anatomy teachers were permitted a small number of human bodies per year. Since opportunities were so limited, it was important that everyone have a good view, so purpose-built theaters were designed. One from the 1590s survives at the University of Padua: an unnervingly small room with six narrow oval galleries rising steeply around the central table. The students leaned forward against the balustrades; there was no room to sit. What with the heat and smoke from the illuminating torches, and the smell of the open cadaver slowly rotting as it went through dissection by stages, it was not unusual for members of the class to faint. The balustrades and the shoulders of their fellow students prevented them from falling headfirst into the scene below.

Even today, nice and clean and empty, the theater in Padua calls to mind Dante’s circles of Hell. Unlike Dante’s version, however, this was not a place that needed a sign telling anyone to abandon hope upon entering. On the contrary, hope was what it was about. The words inscribed at the entrance of the Padua theater were Mors ubi gaudet succurrere vitae: “Where death delights in helping life.”

In the early stages of this new educational method, the corpse, however formidably real and uncompromising in appearance, was still expected to defer to the book. A lowly barber or surgeon would do the cutting, an “ostensor” would point out each part, and somewhere above it all the professor would stand at a lectern reciting from (usually) Galen.

But, awkward: the body sometimes refused to cooperate. For example, Galen had described an organ at the base of the brain known as the rete mirabile, or “marvelous network.” In life, it was supposed to infuse “vital spirits” into the blood, to be further distributed by nerves; the process left a phlegmy residue to be excreted via the brain and down the nostrils. (We can probably all recognize this substance; its familiarity perhaps made the theory sound more credible.) But ostensors blushed for their inability to point to the rete mirabile when it was called for. The Parisian professor Jacobus Sylvius desperately wondered whether it had existed in Galen’s time but then degenerated out of existence in modern humans.

The real reason is simply that humans don’t have it. Dogs do. Dolphins do. Giraffes do, to protect them from blood pressure surges when they lower their heads to drink. But in humans it is just not there. Galen had probably seen it while dissecting sheep. Some commentators began suggesting this, notably Giacomo Berengario da Carpi, a Bologna professor who wrote, “I have worked hard to discover this rete and its location; I have dissected more than a hundred heads almost solely for the sake of this rete and even now I don’t understand it.”

The final blow came from a brilliant former student of Sylvius: Andreas Vesalius, born Andries van Wesel in Brussels in 1514. Besides being an anatomist, Vesalius was an innovative educationalist, a writer, an editor of classical texts, and the creator of one of the outstanding works in printing history—in short, a perfect humanist, but of the kind who subjected ancient authorities to scrutiny and testing.

He began his investigations as a young student in Louvain, where he and a friend would sneak outside the city walls at night to collect easily detachable parts from rotting victims of execution who were displayed at the roadside as a warning. He and his friend used them for a different kind of edification. While still at Louvain, Vesalius also wrote a commentary on al-Rāzī, correcting errors of terminology that had crept in from previous translations and trying to identify the substances referred to: a project in the spirit of Leoniceno.

He went on to study in Paris and then in Padua, where he was so precocious that he was taken on to teach surgery and anatomy the very day after he graduated. He immediately set to devising better ways of preparing bodies for educational demonstration, and, unlike others, he insisted on doing the cutting himself as he lectured. Surviving notes made by a student show how he proceeded through the parts of the body over several days, racing against time and decay as dissectors always had to.

Vesalius’s copy of works on respiration by Galen

To help with this problem and provide more leisurely aids to study, he began working up large printed illustrations. First came a set of six tables, big enough to show the body parts clearly. It did still include the rete mirabile; later Vesalius confessed that he had used a non-human animal as the source, since he was embarrassed to admit not having found it.

That feeling would change as his confidence grew. A couple of years later, he was carrying out dissections in Bologna with his colleague Matteo Corti. Unusually, Vesalius played the role of humble cutter and ostensor while Corti read out the texts. Vesalius became annoyed with Corti’s loyalty to the standard sources, so he kept interrupting to point out where the body differed, until the two anatomists were arguing openly over the body in front of the onlookers. (I see them throwing kidneys and clavicles at each other, but that’s just me.)

At last, in 1543, Vesalius produced his masterwork: De humani corporis fabrica, or Of the Structure of the Human Body, in which he repudiated the notion of a human rete for once and for all. He blamed both himself and other anatomists for having been too Galen-reliant: “I shall say nothing more about these others; instead I shall marvel more at my own stupidity and blind faith in the writings of Galen and other anatomists.” He ends the section by urging students to rely on their own careful examinations, taking no one’s word for anything, not even his own.

This was a good warning, since Vesalius himself did not get everything right. One error was that he failed to identify the clitoris correctly, misdescribing it as part of the labia. It took another Padua anatomist, Realdo Colombo, to correct him. Realdo even knew what it was for, which implies that he had noticed it in contexts other than the dissection table. He named it “amor Veneris, vel dulcendo” (“love of Venus, or thing of pleasure”), gave details of its role in women’s sexual experiences, and remarked, “It cannot be said how astonished I am that so many famous anatomists had not even an inkling of such a lovely thing, perfected with such art for the sake of such utility.”

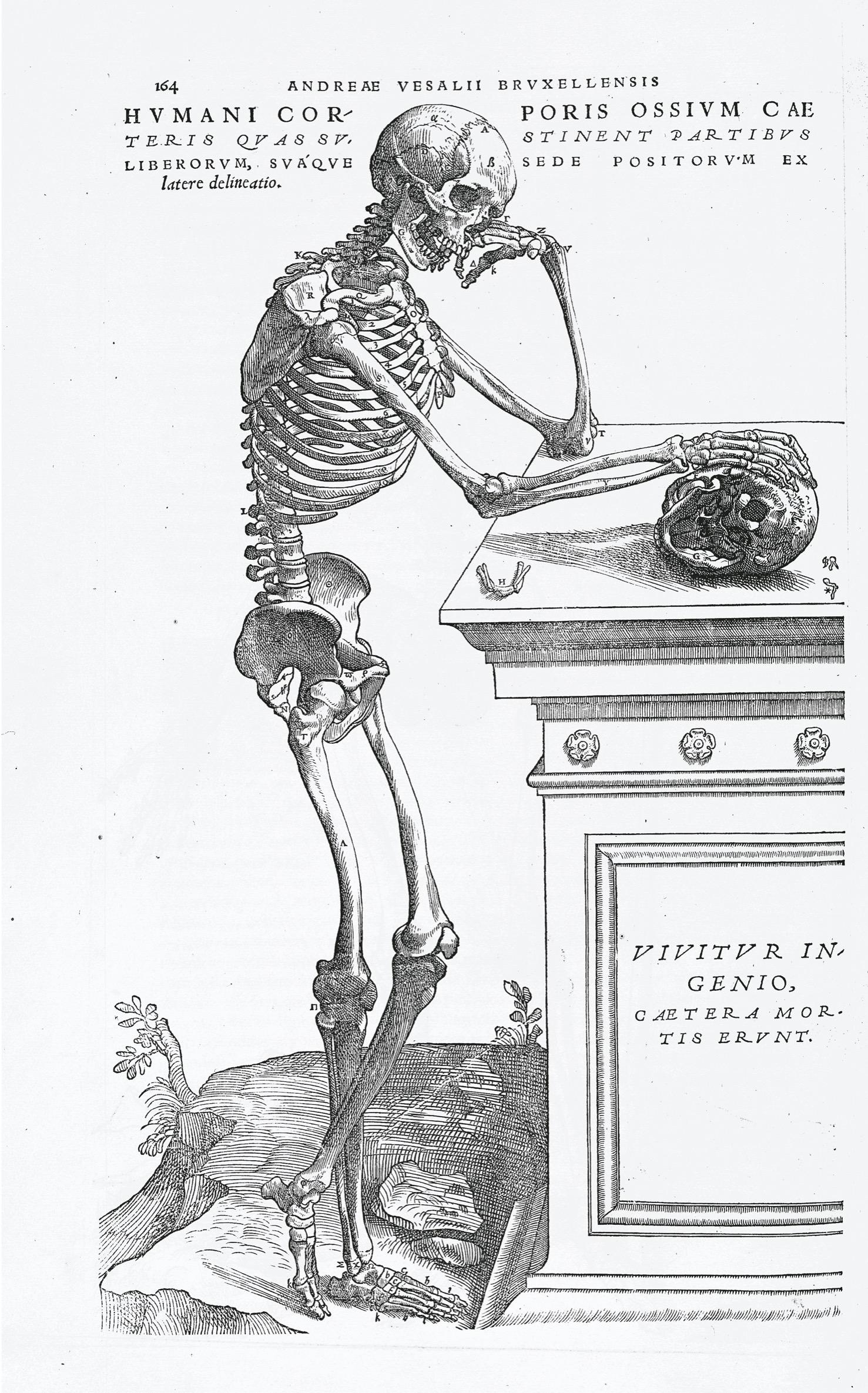

With a few such exceptions, Vesalius’s Fabrica is distinguished by its detail, its description of methods of preparing the bodies, and its judicious assessment of errors in the classical authorities. And, with all this, it is also a superb work of humanistic book-production and visual art. It is printed in a clear, easy-to-read font, and features eighty-three plates of images, drawn under Vesalius’s guidance by Jan van Calcar and engraved by various hands. The engravings were made in Italy on blocks of pear-tree wood, which were then transported by a mercantile firm across the Alps to Vesalius’s publisher of choice in Basel, Joannes Oporinus. The author followed behind, ready to attend every phase of the operation. He constitutes an equally personal presence in the book itself, which includes a portrait of him, with a rather solemn and challenging-looking expression as he demonstrates the muscles in an arm, and a scene on the engraved title page showing him dissecting a body in a packed lecture theater. Balustrades notwithstanding, students and eminent officials—as well as Galen, Hippocrates, Aristotle, and a dog—almost tumble around him in their eagerness to see. The whole work is filled with such stylish touches: cherubs fly around in the capitals, a skeletal figure leans on a tomb contemplating a skull, a muscular man flings back his head in anguish. Many of the figures are shown against natural backgrounds or the scenes of half-ruined classical buildings that so many humanists loved. Their poses are those of heroes, especially when they are displaying the structure of muscles.

It is poignant to see these dignified human beings and to reflect that their models were likely to have been executed as criminals, or else were destitute people who had died in poverty and had no say in the fate of their bodies. They almost certainly never chose to end up on the page like this: right through to the nineteenth century, many people resisted the prospect of being dissected. One reason was that they believed in physical resurrection in the afterlife; no one wants to rise into heaven as an empty torso or a flapping curtain of shredded nerves and muscles. The prospect of helping anatomical students to learn—far from being something to “delight” in, as the Padua motto had it—was considered a powerful deterrent to crime, almost more so than execution itself.

Yet these unfortunate nameless people have indeed made it possible for others to live. And here they are, in one of the most magnificent books in history, in their full dignity, after all: forthright, muscular, and beautiful. They look, many of them, as if they had been sculpted by Michelangelo.

There is a good reason for this similarity: fascinated by musculature and sheer physical heft, as well as by human dignity, Michelangelo made a close study of anatomy in order to improve his art. He was friends with Realdo Colombo, and they planned to produce a book together. This did not happen, but Realdo’s posthumously published anatomy book probably does owe something to their collaboration.

Other artists had conducted anatomical study before, the outstanding example being Leonardo da Vinci. A serious researcher, he undertook deep investigations into the mechanics as well as the beauty and harmony of bodily forms. Early in his career, he drew detailed sections of a human skull and a muscular leg. Later, studying each end of the human span, he dissected a child of two and a man of one hundred. The latter, a pauper in the charitable hospital of Santa Maria Nuova in Florence, told Leonardo almost with his dying words that he felt fine, if a little weak. Leonardo wrote: “I dissected him to see the cause of so sweet a death.”

As with so much of his work, Leonardo kept his results to himself in his notebooks, so that few contemporaries realized what a pioneer of many sciences he was. He was also rather better educated in classical culture than his oft-quoted self-description as an omo sanza lettere (unlettered man) suggests: he brushed up his Latin to compensate for learning it poorly when young, and was the owner of a reasonable number of books (including a copy of Pliny). Leonardo intended to write a full treatise on anatomy, but got no further than an outline: “This work should begin with the conception of man, and describe the form of the womb, and how the child lives in it. . . . Then you will describe which parts grow more than others after the infant is born, and give the measurements of a child of one year. Then describe the grown man and woman, and their measurements . . .” and so on, presumably through to the centenarian stage.

As an anatomical textbook, this would have been extraordinary in also being a narrative account of human bodily life. Artists and anatomists alike knew very well that we do not hold to one unchanging form throughout our lives. Contrary to the image in Vitruvian Man, there is no single, static model for how to be a human being. We are born, we develop, we decline. As Lucretius had said, both spirit and body have “a birthday and a funeral.” Along the path between these events, all is in flux. The mind certainly is. For all our exalted sense of ourselves as spiritual beings, our conscious selves are prone to being befuddled by alcohol or enfeebled by disease. Even the wisest sage can lose her reason in a flash if a stone falls on her head. Lucretius and his ultimate source, Democritus, observed how mind and body alike are affected by the senses and events throughout life; they reminded us that, one day, each of us will come to an end in the gentle, silent dissolution of our atoms. Writers through the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries continued to reflect on these thoughts; a new sensibility was formed around them. Ultimately, as it turns out, neither books nor bodies are completely reliable.