8.

Unfolding Humanity

Mostly 1800s

Bear cubs and seedlings—Three great liberal humanists on education, freedom, and flourishing—Wilhelm von Humboldt, who wanted to be fully human—John Stuart Mill, who wanted to be free and happy—Matthew Arnold, who wanted sweetness and light.

When Simone de Beauvoir wrote, “One is not born, but rather becomes, a woman,” she was putting a new spin on older thoughts by educationalists such as Erasmus, who said that “man certainly is not born, but made man.” Erasmus cited an old legend taken from Pliny: that baby bears were born as formless lumps, and then licked into a proper bear shape by their mothers. Perhaps humans needed to be formed into a human shape, too, at least mentally if not physically.

It was a nice thought for teachers to contemplate, since it made them sound very important. They actually made human beings! But some preferred to say that humans—while needing the guidance of good educators and influences—came out best if they developed their own natural “seeds” of humanity from within. The two aspects of development were not contradictory: the student still needed a good teacher to nurture that growth and ward off bad influences. Even if teachers were there mainly to nudge and guide, rather than to create a shape, they still had reason to feel pride in their work. One could even see them as guiding the whole future development of humanity. If each generation had a better education than the one before, and then produced new teachers in their turn, the result was that great Enlightenment goal: progress. The Prussian philosopher Immanuel Kant promoted this idea in a series of lectures on education in the late eighteenth century: by helping individuals to reach their highest capacity, the teacher also helps generally to “unfold humanity from its seeds.” It would be hard to top that on the importance scale.

Similar visions of education as an unfolding of humanity would live on throughout the nineteenth century, initially in Prussia and other German-speaking lands, then elsewhere as other countries picked up on these (literally) progressive ideas. The approach can be summed up in two German words. One is Bildung, which means “education,” but with an added implication of making or forming an image, since it comes from the root Bild, meaning “picture.” Bildung suggests the making or forming of a person, usually a young man. Life experiences and the influence of mentors help him to develop his complete humanity as he grows, until he is ready to take up his place as a well-rounded personage in adult society.

The other word was Humanismus. Surprisingly, it was not until nineteenth-century German usage that this emerges as a noun describing a whole field of activity or philosophy of life. There had been umanisti aplenty in Italy in earlier centuries, but what they did was not yet summed up as umanesimo. Initially, the German term meant mainly an educational approach based heavily on Greek and Roman classics: that was the context for its first recorded use, by the pedagogue Friedrich Immanuel Niethammer in 1808. It later expanded to denote the whole area of history, language, the arts, and moral thinking, as well as education. By the mid-nineteenth century, German historians were also applying it retrospectively to the Italians of the earlier era: it features prominently in the Leipzig professor Georg Voigt’s 1859 book The Revival of Classical Antiquity, or The First Century of Humanism—a huge survey starting with a long chapter on Petrarch, casting him as the embodiment of “humanitas, all that was uniquely human in the spirit and soul of man.” It also comes up as a theme in the Swiss historian Jacob Burckhardt’s Civilization of the Renaissance in Italy the following year, although Burckhardt was less keen on the book collectors and philologists. He was more excited by figures such as Leonardo da Vinci, the multidimensional, versatile “universal man” of his time. Now the educators of the north wondered if they could produce such figures, or fairly good approximations to them, by means of a new education system. It should be an education aimed at many-sidedness, or complete human harmony, rather than on the narrow business of inculcating skills.

The first person to have a chance actually to put this into practice on a large scale was Wilhelm von Humboldt, the man to whom the Prussian government entrusted the job in 1809 of redesigning their entire educational system for a new era. Prussian education would acquire a reputation for being strict and regimented, yet the man who invented it was startlingly unconventional in many ways, driven by a great personal love of freedom and of humanistic culture. His ideas—those he was able to promote in his lifetime, as well as those he had to keep unpublished for a while—would inspire other educators and thinkers around Europe, including in Britain. They would influence two English writers in particular, and we will come back to them later in the chapter.

But first, Wilhelm von Humboldt. Besides his educational work, he was an art collector, a serious linguist, and a decidedly kinky character in his sex life. Curious to find out what kind of art he collected and which languages he studied? Read on.

Humboldt’s own early “unfolding” took place in a situation of high privilege. He was born in 1767 into the family that owned Tegel, a sixteenth-century mansion beautifully set near a lake on the edge of Berlin. There, he had his education from private tutors, as did his brother Alexander. Despite being two years behind him in age, and also despite doing very little work at his books, Alexander tended to attract more attention. While Wilhelm was a quieter, “inward” type, as he admitted himself, Alexander was mercurial and outgoing. Alexander went on to become an explorer and scientist, renowned for an intrepid five-year expedition to Central and South America and for his multivolume science book Cosmos; he would have literally hundreds of things named after him, from mountains to plants to penguins. Johann Wolfgang von Goethe said of him later, still reeling after one of Alexander’s visits, “What a man he is! . . . He is like a fountain with many pipes, under which you need only hold a vessel; refreshing and inexhaustible streams are ever flowing.”

Wilhelm had his own charm, but it ran in a smooth stream rather than bubbling like a fountain. Although he also had some interest in the sciences and natural history, what really excited him were the humanities, especially languages, the arts, and politics. In those fields, and in his “inward” way, he became just as adventurous and just as much of a maverick as Alexander, determined to live by his own lights. He was studious but not solemn: his daughter later described him as being habitually “merry and witty,” as well as showing “perfect goodness and kindness.” Things would be named after him, too. It is just that they were schools and universities rather than penguins.

As the two boys grew older, they went to university together, their tutor rather oddly accompanying them. In 1789, two things happened in Wilhelm’s life. While he and another tutor were traveling in France, the French Revolution broke out. They rushed to Paris so Wilhelm could have the educational experience of witnessing it. What he saw did not convert him to revolutionary politics, but he was struck by the general atmosphere of freedom in the air, as well as by the extreme poverty still so evident in the city. This led Wilhelm to write: “How few people study human misery in all its horrible extent, and yet what study is more necessary?” The feeling that it was essential to study human life and experience remained with him.

The other event of 1789 had its origin in his own reasonings, rather than in outward events. He laid out these thoughts in a tract, “On Religion,” written while he was still a student. It discussed the contentious issue of whether the state was entitled to tell people what to believe, an idea once thought obviously true (at least by the authorities), but questioned through the long Enlightenment period by philosophers including John Locke and Voltaire. The young Humboldt was also inclined to question it. Two years after that first tract, he incorporated his conclusions into a longer political work: Ideas for an Attempt to Define the Legal Limits of Government. That is a literal translation from the German, but it came out in English in two alternative versions, called The Sphere and Duties of Government and The Limits of State Action, respectively. It doesn’t matter what you do with it; the title remains less than thrilling. The contents, however, were bold.

Humboldt’s subject was the state in its self-appointed role as moral and ideological arbiter for people’s lives. Government authorities, he writes, seem to feel it their duty to impose some particular religion or dogma on their society, because they think that otherwise everything will turn into immorality and chaos. Humboldt disagreed, and for humanistic reasons. He had a humanist’s view of morality: he thought that its seeds lie in our own natural predisposition toward kindness and fellow feeling. Such impulses need guidance and development, but they do not need replacing by state-imposed commandments. For Humboldt, principles such as love or justice harmonize “sweetly and naturally” with our very humanity, but for this harmony to have any effect, there must be a free field of operation. If the state imposes moral principles by diktat, it obstructs their natural development. Thus, in effect, a state that enforces a particular belief is denying people the right to be fully human.

So Humboldt advises the state to limit itself, at least where matters of individual humanity and morality are concerned. People should be able to explore these things in their own way—with one proviso, however. If their actions lead them to encroach on the development or well-being of others (say, through violent or destructive behavior), then the state should intervene to stop them. Humboldt thus asserts the key principle of political liberalism. The government is not there to tell people whom to marry, or what to believe or say, or how to worship, but mainly to make sure their choices do not harm others. We do not need a grand moral vision from our state; we need it to provide the underlying conditions for a decent life, and for our freedom.

And similar principles apply for Humboldt in matters of education. Human character develops best when it is “unfolded from the inner life of the soul, rather than imposed on it or importunately suggested by some external influence.” For that to happen, we need good humanistic teachers, but we do not need or want intrusive rules by the state.

This is not a philosophy likely to appeal to any traditionalist regime. (It has little to offer revolutionaries, either; they are more likely to want a radical transformation in every aspect of society, which does eventually mean intruding on individuals’ quiet lives and private choices.) It may seem strange that the man who wrote this book would one day be entrusted by the authorities with the job of designing a major national educational program. But almost no one knew that he had written it, because the book was unpublishable. He did try to get it into print, with help from his friend the playwright Friedrich Schiller, but Schiller managed to have only a few sections published in periodical form. The work as a whole did what humanistic works frequently do: it went into the author’s desk and stayed there for decades. Occasionally Humboldt would look through it again and make amendments, but mostly it just waited.

In the meantime, he became an eminent Establishment figure. He moved around Europe, taking up governmental and diplomatic postings: he lived at various times in Rome, Vienna, Prague, Paris, and London. This solid career was what made him a good choice when the Prussian education project came up in 1809. Humboldt applied himself to it systematically—but he also seems to have seen an opportunity at last to put some of his liberal ideas into practice. His reforms combined his love of Bildung with his belief that young people would develop their “humanity” best if they could have as much freedom as seemed feasible.

For the earlier age groups, he believed that everyone should start with the same all-around foundation. (All boys, that is, since like everyone else in his world, he did not think to include girls in the system.) Instead of working-class children being immediately trained for a vocational skill, they would start with a general Bildung aimed at forming good character. Education at all levels was not to be primarily about acquiring skill sets, but about creating human beings with moral responsibility, a rich inner life, and intellectual openness to knowledge. Having all this, people would be able to continue in a well-formed way in whatever course of life they adopted.

Those with scholarly aptitudes could advance to higher levels. By the time they reached university, they were expected to be able to manage most of their learning for themselves, seeking knowledge through seminars and independent research more than by passively listening to lectures. University education, Humboldt said, should mean “an emancipation from being actually taught.” Even after students graduated, that should not mean the end of education. He believed in lifelong learning, rather than in getting through school and then forgetting the lot.

In some ways, this was a vision very much of its time, not least in its taking no account of girls. But in parts it almost sounds like some of the radical educational experiments of the mid-twentieth century—although they would take the freedom element a good deal further. Humboldt’s principle was not “anything goes”; he sought to allow and foster the development of truly harmonious, many-sided humans. His vision of humanity and freedom remained at the heart of the Prussian educational system and went on to influence educational thinking elsewhere. Questions were raised that we are still wrestling with in our own time: What is a humanistic education for? If the aim is to create fully rounded, responsible citizens, how do you quantify this target? How do you justify it financially, or politically? What is the right relationship between useful-skill learning and the more nebulous benefits of an all-around Bildung? How much freedom should the student have, and what is the role of the teacher as a personal presence in the student’s life? And how do you put a value on continuing to learn after the career-training years? These questions go beyond educational theory to touch on deeper questions of what we want in life generally.

Humboldt himself certainly loved pursuing his own lifelong learning. He was never happier than when left quietly to research some intellectual project—and the subject of his researches was often, in one form or another, that elusive thing: the human. As he wrote in a letter:

There is only one summit in life: to have taken the measure in feeling of everything human, to have emptied to the lees what fate offers, and to remain quiet and gentle, allowing new life freely to take shape as it will within the heart.

This pursuit gave him so much pleasure that, perhaps naively, he imagined that it would be fulfilling for many other people, too—but he knew it could only be encouraged, never forced. Life must freely take shape in each of us. And, besides applying his belief in freedom to education, government, and religious belief, Humboldt applied it in his personal life.

He was married, to Caroline von Dacheröden (or “Li,” as he always called her); they had children and seem to have been happy together. But both his ideas and their practice were unconventional. In the secret tract on the role of the state, Humboldt had already suggested that freedom should also mean trusting people to work out their own choices in marriage and sexuality—again, so long as no harm was done, and so long as the situation was consensual. Otherwise, each marriage should mostly be allowed to follow its own course, just as each human individual should. A marriage has its own character; it comes from the characters of the two people involved. Making it conform to an external rule is unhelpful. The state’s task, as always, is to protect people from harm and otherwise to allow them to do as they wish.

Thus, Caroline took other lovers, sometimes spending more time with them than with him. And Wilhelm pursued his fantasy life. I mentioned that his sexuality was unorthodox; we know about this only because he wrote about it—not in published form, of course, but in his journal, where he recorded his daydreams. What fascinated him was the idea of struggling to subdue physically strong working-class women, in various situations. One woman, for example, particularly caught his eye when he saw her working on the ferry that crossed the Rhine. Sometimes he explored such scenarios with prostitutes, but at other times he just fantasized. What makes this so interesting is that, in writing about it, he also reflected on both its origins and its effects in his own psychology. Long before Sigmund Freud made such an idea seem obvious, Humboldt wondered in his journal whether such desires might shed light on other aspects of human nature. He speculated that leading a life of such vivid sexual imagination had also helped to form his whole path in life: it made him more “inward.” It also fed his interest in human relationships, and in “the study of all character”—the central pursuit of his intellectual career.

So, does the Prussian educational system owe something to Wilhelm von Humboldt’s sex kinks? Yes, in a way! But even more interestingly, both sides of his life show how engrossed he was in the general question of human nature, in all its complexity and changeability.

The unusual aspects of his relationship with Caroline had another fortunate consequence: as they were often apart, we have a voluminous correspondence between them, which we would not have had if one of them had always been in the drawing room and the other in the study. His letters to her are a rich resource, filled with his reflections on humanity, on education, and on his other research interests. He was a good correspondent in general—one of those copious letter writers to set alongside Petrarch, Erasmus, or Voltaire. Having lived in so many parts of Europe, he knew people everywhere, and was always interested in them, despite his inwardness. As he wrote in one of his letters to Caroline:

The more in life one searches for, and finds, human beings, the richer, more self-sufficient, more independent one becomes oneself. More humanized, more readily touched by all that is human in all the facets of one’s nature, and in all aspects of creation. This is the goal, dear Li, to which my nature urges me. This is what I live and breathe. Here for me is the final key to all desire . . . Who, when he dies, can tell himself, “I have comprehended as much world as I am able, and have transformed it into my humanness,” has fulfilled his aim.

After all these experiences, however, what he loved most was to go home to the estate of Tegel—which he and Alexander had now inherited from their parents. Wilhelm had the place completely rebuilt in the early 1820s, turning it into a mansion in the neoclassical style. He and Caroline spent time together there; they developed an art collection, which especially featured a form very popular in German lands at that time: copies made in plaster of the great classical sculptures and statues of Rome and Greece. Wilhelm enjoyed the company of their children, and later of his grandchildren. He read and wrote and studied.

Above all, he pursued his greatest intellectual passion: the study of language. He considered this the key to studying humanity itself, since we are cultural creatures who live largely in the world of symbols, ideas, and words. He wrote to Caroline: “It is only through the study of language that there comes into the soul, out of the source of all thoughts and feelings, the entire expanse of ideas, everything that concerns man, above all and beyond everything else, even beauty and art.”

One benefit of his jobs in other countries had been the opportunity to immerse himself in their languages. He had learned Basque while spending time in or near the Spanish peninsula, and he worked on Etruscan inscriptions during his period in Rome. He studied farther-flung languages, too: Icelandic, Gaelic, Coptic, Greek, Chinese, Sanskrit. Alexander brought back materials from his travels so that Wilhelm could learn a little about Native American languages.

As time went on, Alexander became a more frequent visitor at Tegel—a place he had mostly avoided earlier in life. He would come and amuse Wilhelm’s family by bringing stories and political news from the world outside. Wilhelm, by contrast, liked to claim that he never read a newspaper: “You are sure to hear what is important, and can spare yourself the rest.” The contrast between the two brothers was as clear as ever: one looking outward, one inward; one following the fountain flow of current events, the other immersing himself in deep, long studies of culture.

Caroline died in 1829, and Wilhelm’s remaining years at Tegel were dedicated to his final project: the study of Kawi, the priestly and poetic classical Indonesian language of Java. He hoped to write an authoritative study, and began by writing an introduction, which became as long as any ordinary book. It discussed his general theory of languages: with his usual holistic approach, he saw them as expressions of each particular culture’s entire view of the world.

But time ran out on him, and he never finished the rest of the book. Five years after Caroline’s death, his own health went into a decline. His daughter Gabriele von Bülow came over from her home in England to help him, bringing her children; ever the linguist, Humboldt was impressed by the careless way these cosmopolitan youngsters mixed German and English in their speech. In March 1835, he developed a fever and drifted into semiconsciousness, during which he, too, murmured multilingually, in French, English, and Italian. At one point, he said clearly, “There must be something to follow—something to come still—to be disclosed—to be . . .” The family gathered around him in his final days. On April 8, he asked for a portrait of Caroline to be taken off the wall and brought to him. He pressed a kiss to it, with his finger. Then he said, “Good-bye! Now hang her up again!” With these last words, he died.

The Humboldtian model of education would have a widespread influence, and in large parts of German-speaking territory it remained dominant well into the twentieth century—until 1933, that is, when the Nazis came to power and threw out its humanistic ideals entirely. They replaced Humboldt’s model with a giant indoctrination machine, designed to turn boys into warriors and girls into mothers for producing more warriors. The forming of well-rounded, fully human, free, cultured individuals had no place in the Fascists’ world. They had no wish to “humanize” anyone; quite the opposite.

Along with the afterlife of his educational ideas, Humboldt’s youthful political ideas about freedom would have an afterlife, too. When he died, his heirs began going through the papers in his study, and they found—still there after half a century—the tract on the limits of the state. It finally saw publication, thanks to Alexander, who did the formidable labor of preparing a multivolume collected edition of Wilhelm’s works. The Limits came out as part of that, in 1852.

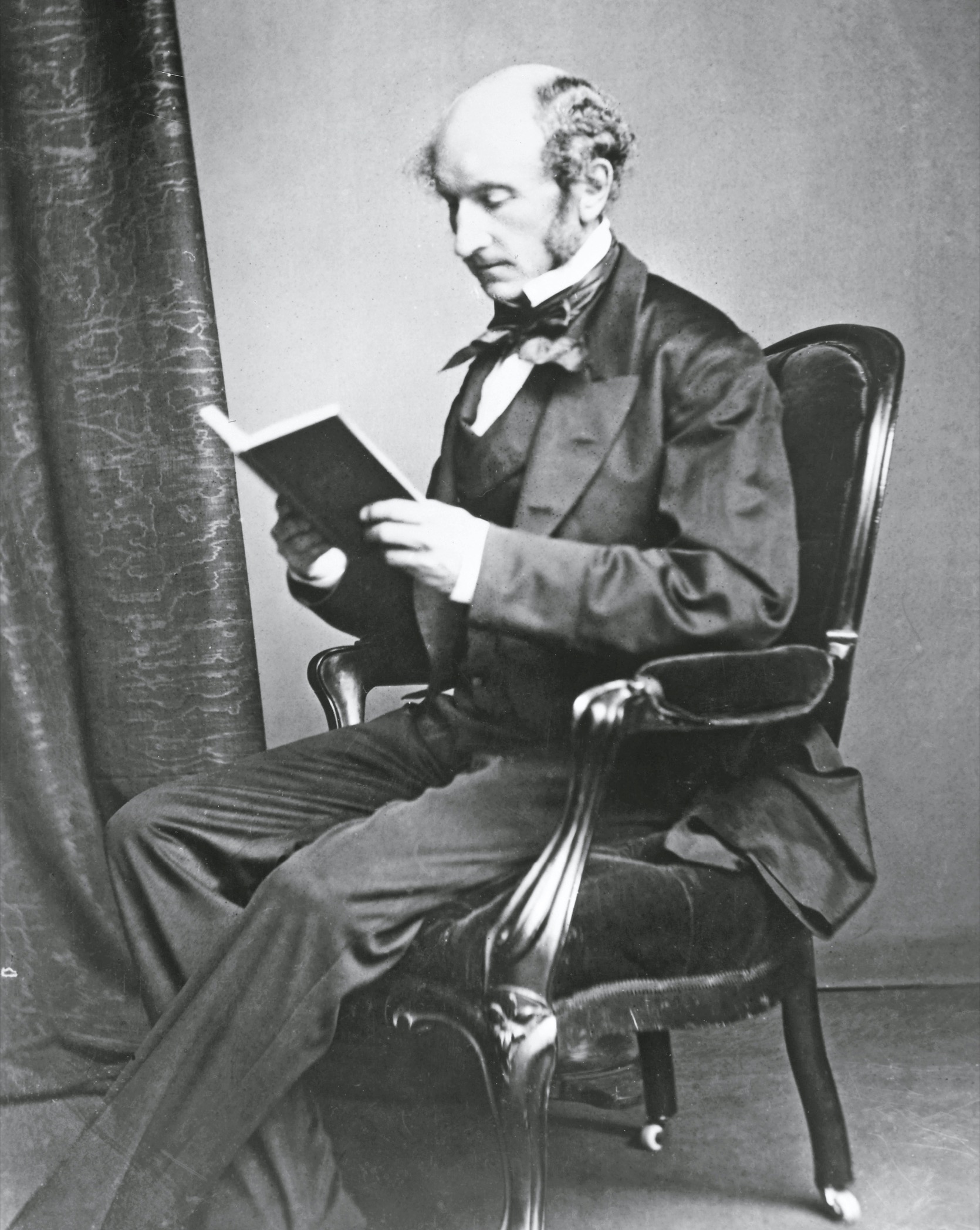

It was translated into other languages, including English, and promptly caught the imagination of English readers. Among those who read it was one of the most important liberal thinkers of that later generation, John Stuart Mill, along with the collaborator and partner whom he had just married: Harriet, formerly Taylor, now Mill.

We met the Mills in the previous chapter, in the context of their feminism. Harriet’s arguments for women’s right to aspire to the largest and highest “proper sphere for all human beings” struck a strongly humanist note. John, meanwhile, developed a full-scale theory of political liberalism. His own feminism and his discussions with Harriet were powerful influences on this, and so was his reading of Wilhelm von Humboldt. In 1859, when he published his own very influential short work, On Liberty, he prefaced it with a quotation from Humboldt’s rediscovered book on the state:

The grand, leading principle, towards which every argument hitherto unfolded in these pages directly converges, is the absolute and essential importance of human development in its richest diversity.

Mill’s subject is liberty, but by quoting this at the outset, he plants that liberty firmly in a broader humanist tradition. The two words featured in those lines, diversity and development, would always go together with the word freedom in Mill’s thinking. Each of those three nourished the others. For him, we become fully developed human beings if we have freedom, but also plenty of contact with the diversity of ways in which one can live a human life—including even the most eccentric possibilities. A liberal society lets us develop our own such possibilities through contacts with diversity, all taking place in a culturally rich environment and without state interference. Except, of course, if what we do hurts others. For Mill, as for Humboldt, the state’s task is to step in if my own pursuit of freedom and experience is damaging yours. The state has no business telling people what they should do: it is no part of its role to define a single perfect form of life or morality. Its role is to enable each of us to have the space we need to stretch ourselves, without robbing others of their space.

For Mill, too, the right approach to education is crucial, and here again, he stressed diversity. We need experiences that make us expand, and this means making “experiments in living.” Humboldt, too, had written of how we learn best through a “variety of situations,” rather than through aspiring to a unitary model of life. Moreover, the encounter with variety helps make us more tolerant: as Montaigne had said, speaking of the benefits of travel, “So many humours, sects, judgments, opinions, laws, and customs teach us to judge sanely of our own.”

Thus, Mill recommends that a liberal society support “absolute freedom of opinion and sentiment on all subjects, practical or speculative, scientific, moral, or theological.” This includes supporting the freedom to express all this openly, since a freedom that must be kept secret is no freedom at all. He does note that such expressions may offend sensibilities; it may mean that people will do things that others consider “foolish, perverse, or wrong.” That is not a problem unless it causes real harm to those others. (Of course, defining “harm” is so complicated that we are still arguing about it today.)

On Liberty also hinted at other implications, especially for sexuality and religion. Mill believed, like Humboldt, that individuals should be free to work out their relationships for themselves, with the usual no-harm clause. Like Wilhelm and Caroline, he and Harriet had an unconventional relationship, although this time no ferrywomen were involved (so far as we know). For twenty years after they met and fell in love, the couple were unable to marry, because Harriet was already married to someone else and divorce was almost impossible at the time. Her husband, John Taylor, sounds like a nice chap, but they had married when Harriet was only eighteen, and she realized only later that they were not well matched. When she met Mill, she fell for him mainly because he was someone with whom she could talk philosophy and politics and morality for hours. They developed from being passionate friends to being lovers, and eventually they began (more or less) living together, by discreet agreement with John Taylor. To avoid distress all around, they kept to a quiet life in a suburb well away from fashionable society. This continued for some fifteen years, until John Taylor died, of cancer, in 1849. Once a decent period of mourning had passed, she and Mill married, but with some adjustments added to the standard wedding vows. Marriage, at that time, gave the husband almost total control over his wife’s affairs, including over her property. Such control could not legally be renounced, but at the wedding Mill read out a “Statement on Marriage,” noting that he disagreed with those rights and promising never to exercise them. Thus, like the Humboldts, they rejected the predefined path laid down by the state, and chose the principles that suited their views.

The other delicate matter was religion, and here Mill’s feelings varied through his life. In his late years, he seems to have considered the possibility that there was an abstract, deist-style God out there somewhere, remote from human affairs. But on the whole he showed no sign of even that belief. Very unusually for the time, he had been brought up without religious indoctrination: his father, James Mill, was an agnostic who had rejected his own Presbyterian upbringing in favor of the utilitarian philosophy of his friend Jeremy Bentham. So John was indoctrinated with that instead. Let us wind back to his childhood for a moment.

Immersion in utilitarian theory had been just one part of what was surely one of the strangest experiments in child-rearing since Montaigne’s father had tried to make his son a native Latin speaker. James did not do that, but he did homeschool his children and gave John an astonishingly early start on the classics. The toddler was learning Greek by the age of three, using Aesop’s Fables; afterward he moved on to Herodotus, Xenophon, and Plato. Latin was added when he was about seven. He also acquired the job of teaching what he learned to his younger siblings as they grew up behind him. Each morning, his day began with a pre-breakfast walk, taken with his father in the pleasant, still-rural area around their north London home at Newington Green. This should have scored high on the happiness-o-meter, except that while they walked John had to give a verbal report on whatever he had read the day before, then listen as James held forth on “civilization, government, morality, mental cultivation.” Finally, John had to repeat the gist of these arguments back in his own words. It would be nice to know what his mother, Harriet Barrow Mill, thought of all this, but—oddly for a feminist—James never mentions her in his autobiography.

At first, John absorbed his father’s influence, and as a youth he founded his own little Utilitarian Society with a membership of three. He continued to develop and use utilitarian ideas later: you can see them at work in the balance of liberal benefits and harms described in On Liberty. At the age of about twenty, however, he went through an experience that changed his perspective on such balances. He fell into a depression. It produced the sort of accidia that Petrarch had suffered five centuries earlier: an inability to feel pleasure in anything. This threw doubt on the felicific calculus. What was the point of counting happiness units if, for deeper reasons, you could not feel that happiness?

Mill’s path out of this came partly through an unexpected discovery: poetry. Neither his father nor Bentham had ever seen the point of it; Bentham flippantly defined a poem as writing with lines that failed to reach the margin. Now, rebelliously, John fell in love with the form, and particularly with the work of William Wordsworth, filled as it was with gushing emotion and love of nature. Wordsworth also tried, in his Prelude, to trace the unfolding and development of an individual’s inward experience from childhood on: a very Bildung-ish thing to do.

Reading Wordsworth made Mill reflect that humans need such deeper satisfactions, in a way that other animals do not seem to. We long for meaning; we crave beauty and love. We seek the fulfillment to be found in “the objects of nature, the achievements of art, the imaginations of poetry, the incidents of history, the ways of mankind, past and present, and their prospects in the future”—all the aspects of culture. (One thinks of Giannozzo Manetti, in his treatise On Human Worth and Excellence: “What pleasure comes from our faculties of appraisal, memory and understanding!”) Happiness is still the good to be sought, but from now on, Mill knew that some forms of happiness were more meaningful than others. One such form is that feeling of being free, “alive,” and “a human being,” which he would write about in The Subjection of Women. Strict utilitarianism cannot easily accommodate this: instead of countable happiness units, we are taken back to qualities that are incalculable and immeasurable. But what Mill’s new approach loses in rigor, it gains in subtlety. His version is more human than Bentham’s.

As well as improving utilitarianism, Mill’s human element improves liberalism. It distinguishes it, for example, from the travesty now described as “neoliberalism,” which allows the rich to pursue profit without regulation while the rest of the population is left to deal with the consequences of such ravaging of society. For Mill, as for Humboldt, this is not what freedom means. A truly liberal society both values and enables deeper fulfillments: the pursuit of meaning and beauty, the diversity of cultural and personal experiences, the excitement of intellectual discovery, and the pleasures of love and companionship.

Mill always said that Harriet contributed much of the thinking that went into On Liberty, as well as into the much later Subjection of Women, although he did not go so far as to put her name on the title page of either work. Had he done so, he would have had to do it posthumously, since she did not live to see the publication of either. She died in 1858 of a respiratory disease that was probably tuberculosis, while they were in Avignon on their way farther south in search of sunshine and healthier air. In his grief, having buried her there, Mill even bought a house nearby, so that he and her daughter (by Taylor) could remain in the area. He wrote an inscription for her tomb. Full of praise for her achievements, it includes the line “Were there but a few hearts and intellects like hers, this earth would already become the hoped-for heaven.” He does not mention any other kind of heaven: her afterlife, as with that of other humanists, was to exist solely in human memory, through the effects of her deeds and writings.

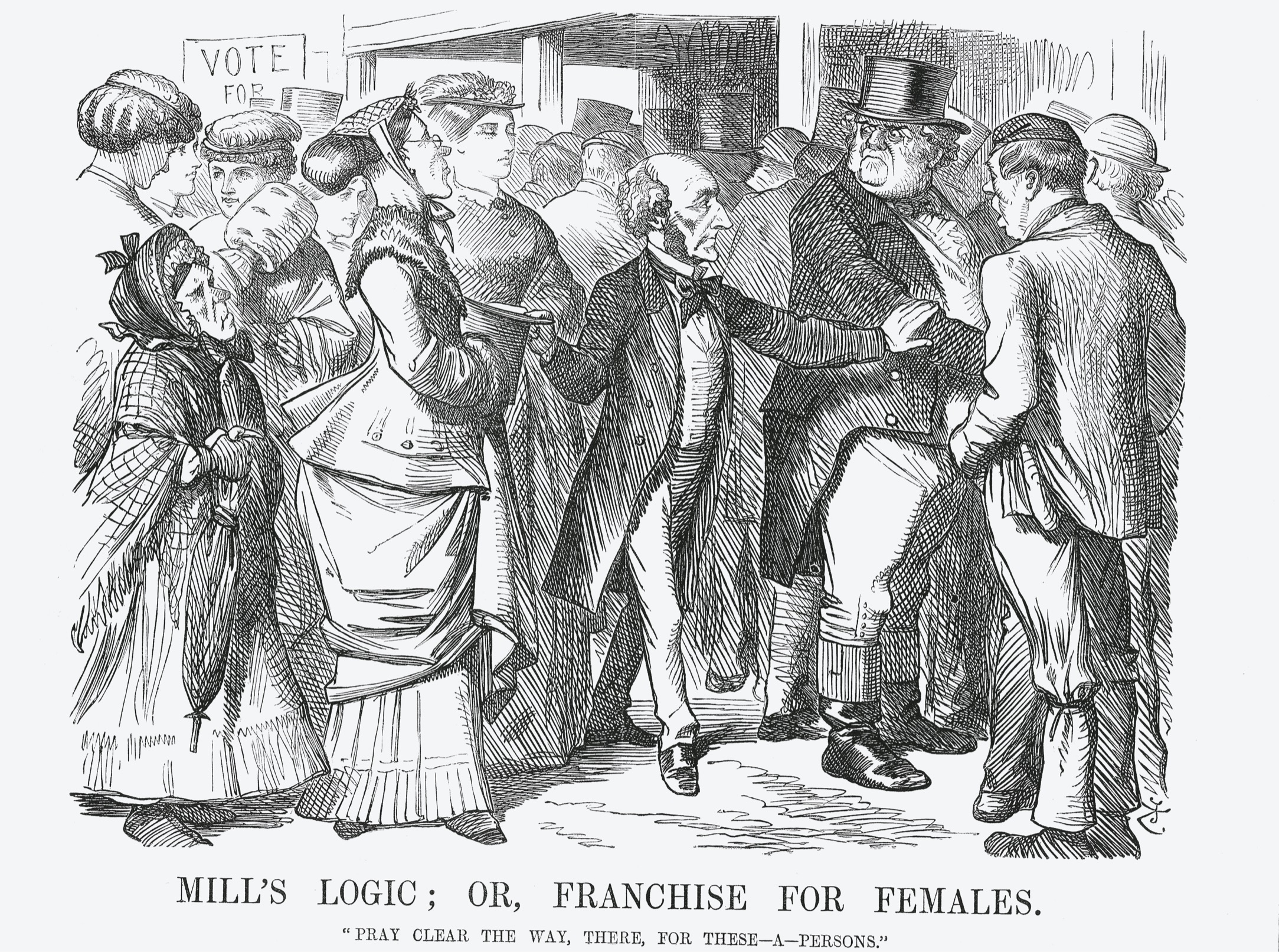

Mill continued his work in politics and philosophy, and put his feminist ideas into practice in 1865 by running for the British parliament, partly on a platform of extending the vote to women. He won the seat, but when he proposed a women’s suffrage amendment to an electoral reform bill of 1867 (he suggested changing the word “man” to “person”), it failed. The parliamentary debate around it was a step forward, however, and he came to look back on this as his most important achievement in this role. Five years later, in 1873, he died, and was laid to rest with Harriet in the Avignon grave.

The ideas of Humboldt and the Mills remain at the foundation of liberal society today, not only for their thoughts about freedom but for their humanism: their vision of a society based on human fulfillment, in which each of us can unfold our lives and realize our humanity to the utmost. No society can claim that it has achieved such a thing to perfection—far from it. But arriving at static, ideal perfection never has been a liberal goal, or a utilitarian one. Or, indeed, a humanistic one. The goal in all three cases is to create just a little more of the good stuff in life, and less of the bad stuff.

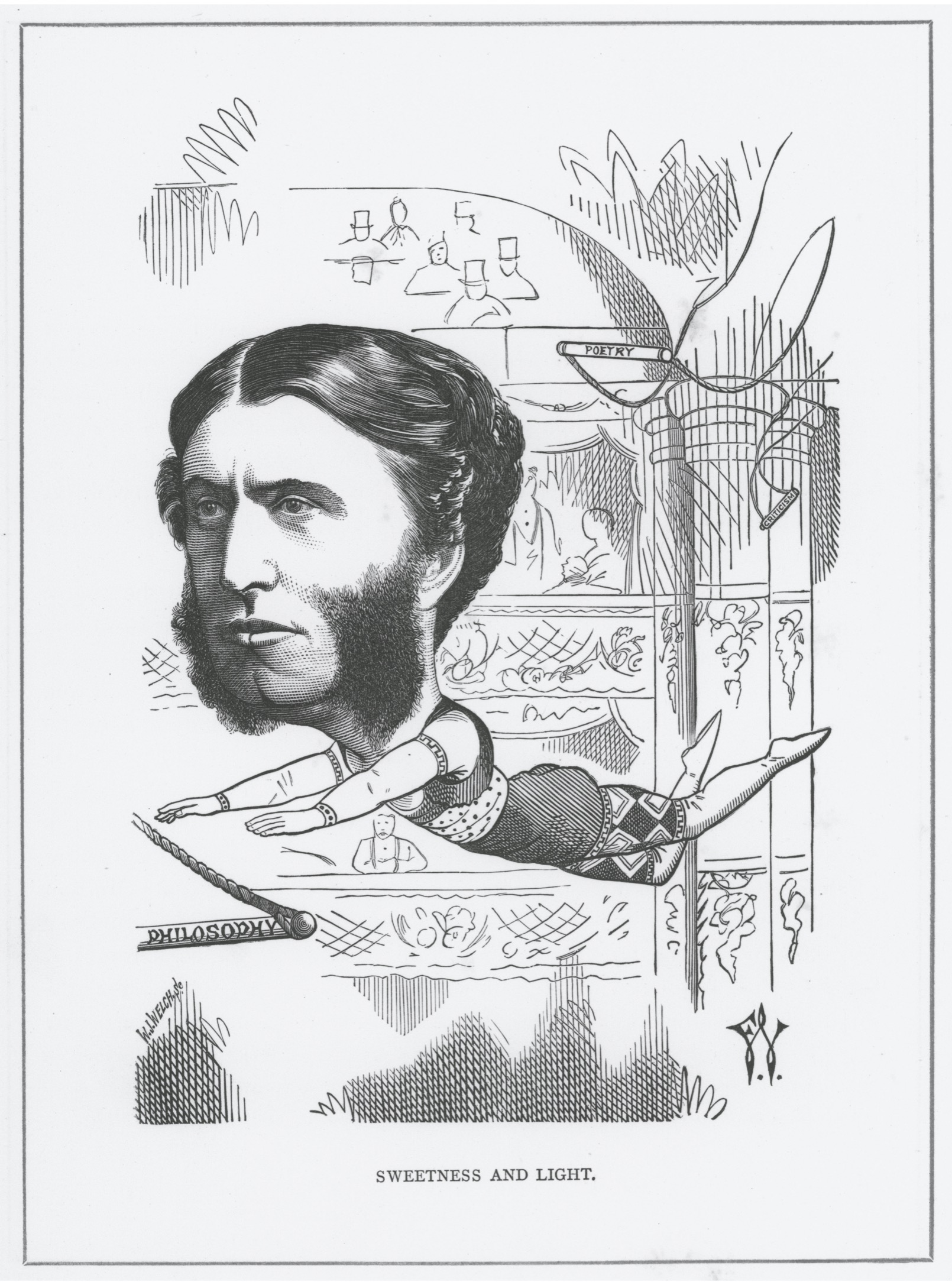

Also inspired by Wilhelm von Humboldt was another Englishman, Matthew Arnold. A poet, a critic, and a witty and controversial essayist, he was also a professional educator who spent thirty-five years inspecting schools around the country, as well as writing reports on the systems of other countries—all in the attempt to improve the level of human unfolding.

There was certainly a lot of room for such improvement. Schools for the poor in Britain were of variable quality. Arnold argued for bringing them all to a consistent standard, and raising that standard several notches, mainly by introducing better cultural materials into classrooms. You can tell he has been reading Humboldt when he writes, in his 1869 study Culture and Anarchy, that the goal of such reforms is to make it possible for us to develop “all sides of our humanity.” Also Humboldtian is that he takes this to mean all levels of society developing their humanity together. No one should be left behind: we are “all members of one great whole, and the sympathy which is in human nature will not allow one member to be indifferent to the rest, or to have a perfect welfare independent of the rest.” Instead of being content to develop alone, the individual should be “continually doing all he can to enlarge and increase the volume of the human stream sweeping thitherward.” Arnold has me at “thitherward.” I’ve long thought the family of terms including thither and thence (“to there” and “from there”) should be brought back into usage, and here he is doing something even better.

Matthew Arnold had grown up in an educational environment, as his father was Dr. Thomas Arnold, the vigorous and very Christian headmaster of Rugby School. Matthew went on to study at Oxford, and may have developed doubts about religion while there; the theme continued to trouble him, and often crops up in his poems. (We will return to that point in the next chapter). He married a devout woman, Frances Lucy Wightman, known as “Flu.” Unlike the Humboldts and Mills, the Arnolds’ marriage followed a more conventional path—but one marked by much sorrow. At the time Thomas was revising Culture and Anarchy from a lecture into a book, they were in mourning for two children lost within a single year, most recently their oldest son, Tommy, who died after a fall from his pony.

Yet somehow, Culture and Anarchy came out sparkling with wit and playfulness, as well as advancing serious arguments. Arnold’s overall point is that anarchy, which he deplores, can be warded off by means of culture, which he admires. But much happens along the way. He surprises and amuses the reader with his turns of phrase; he knows how to make the humanistic heart swell with enthusiasm at regular intervals. He can charm you into assent even when making somewhat absurd or ill-supported claims. At times, you can only look on perplexed as he rides some idiosyncratic hobbyhorse off into the distance for a page or two; eventually he trots back. Above all, he shows an almost willful tendency to confuse people by using words to mean things they normally don’t mean. Thus, he borrows the term “Hebraism” from the German Jewish poet Heinrich Heine, but mostly uses it to denote Christian Puritanism. When he speaks of the “Barbarian” social class, a careless reader may think he is talking dismissively of the lower orders, but no; he uses it for the aristocracy. (The working class is “the Populace,” and the middle classes are “Philistines.”)

Also misleading are two key phrases that he repeats often in the book. One is the statement that “culture” can be defined as “the best which has been thought and said in the world.” The other is also a definition of culture, this time as whatever brings “sweetness and light.”

The first of these, “the best,” sounds elitist, implying high things accessible only through rarefied tastes and an exclusive education. But Arnold is emphatic in rejecting the tendency of the middle and upper classes to feel that all culture somehow belongs to them by birthright, whether or not they ever touch a book or look at a work of art. For him, real culture is accessible to all, and it comes from an “eagerness about the things of the mind.” It means curiosity and the questioning of received ideas; it means “turning a stream of fresh and free thought upon our stock notions and habits, which we now follow staunchly but mechanically.” This is the exhilarating sense of expanding into the human world that Humboldt described in his letters. It is also the widening of life that Mill believed came from encountering diverse life experiences. You can be cultured even if you only read a newspaper, said Arnold, so long as you read it with a free, fresh, and critical mind.

Developing such a mind is difficult, however, if you have not had sufficient exposure to high-quality material, which is why education is important. And it should be the right kind of education. Even the poorest members of society should have access to good, original works of art and literature, not the dumbed-down pabulum that is often given to them in the belief that pre-chewed and undemanding things are all they can handle. For Arnold, there is a challenge for the educator here: to find ways of presenting the best culture in its original richness, while also making it accessible. What must be done with culture is “to humanise it, to make it efficient outside the clique of the cultivated and learned”—and still to keep it “the best knowledge and thought of the time.”

The other phrase, “sweetness and light,” is even worse in its suggestion of fairy-like sugary fluffiness. In fact, it comes from a scene in Jonathan Swift’s “Battle of the Books,” itself drawn from sources in the Latin poetry of Horace. In Swift’s satire, a spider and a bee have an animated discussion about which of them is better. I am, says the spider, because I am an original creator. I build from my own silk, needing nothing else. I am, says the bee. You may be more original, but all you can create is cobwebs and venom. Instead, although I collect my pollen from flowers, I use it to produce honey (sweetness) and wax for candles (light). For Arnold, too, culture feeds on many secondhand experiences but turns them into something fresh and illuminating. There is nothing fey about the “light” he means; it is more like the intellectual light that the Petrarchan humanists felt they were liberating from the monastic cells—or perhaps the Enlighteners’ light of reason.

Culture and Anarchy is a book from which you can read different messages, depending on your inclinations. Conservatives often took it to heart because they shared Arnold’s horror of “anarchy,” specifically the public disorder and street demonstrations that were a feature of British life at the time of publication. Privileged himself, Arnold could see no call for people to behave in such an uncouth and unharmonious way when they could be reading Horace instead. Yet some of what he says is remarkably forward-looking: he is against exclusivity, and open-minded in his support of critical and curious thinking. He also describes himself as a liberal. At the heart of Culture and Anarchy are humanist ideas of an enduring vintage: that our shared humanity connects us all, and that no one has a right to condescend to others or dismiss them as unimportant.

Arnoldian thinking does have a certain air of earnestness, which was carried forth during its long afterlife of influence in Britain and elsewhere. It was a force behind the foundation, in the twentieth century, of the British Broadcasting Corporation, which aimed at enlightening and informing as well as entertaining the masses. It lay at the center of countless institutions of adult education founded earlier in that century, such as the Workers’ Educational Association, established in 1903.

It also had an impact on the publishing industry, which had a very Arnoldian phase in America and Britain alike. Sets of “Great Books” could be good earners for publishers, since Shakespeare and Milton required no royalty payments. Even translations could work well, despite the need for translators. One early series, Bohn’s Standard Library, published many Greek and Roman classics in English, although it did frustrate readers by leaving any lines referring to sex in their original languages.

Then came such outstanding productions as Dr. Eliot’s Five-Foot Shelf of Books, the name bestowed on the fifty-one-volume set of literature edited in 1909 by Charles W. Eliot, the president of Harvard University. In Britain there was the Everyman’s Library, founded in 1906 by J. M. Dent, the working-class son of a housepainter. Unfortunately, Dent’s own habit of shouting “You donkey!” at members of his staff on a regular basis suggests that he was not a fan of every man or woman himself. Those employees were, in fact, the secret of the publisher’s success, especially the series editor Ernest Rhys, a coal-mining engineer who had run reading groups for miners before shifting to the book world. He gave the series its ethos: the books must be cheap yet designed to the highest standards. Each sported an attractive woodcut title page and the dolphin-and-anchor printer’s device of Aldus Manutius—a tribute to that pioneer of clear, well-printed, portable books.

To help readers find their way around such abundance, lists of Arnoldian “bests” began to appear, such as the “Best Hundred Books,” chosen in 1886 by the director of the Working Men’s College, Sir John Lubbock. Besides the usual Eurocentric choices, he recommended such works as Kongzi’s Analects and potted versions of the Mahābhārata and the Rāmāyana. He did admit that he had not personally enjoyed everything on the list: “As regards the Apostolic Fathers, I cannot say that I found their writings either very interesting or instructive, but they are also very short.”

The list included other ideas, added by well-known figures whom Lubbock approached for suggestions. John Ruskin said he wanted to see more books on natural history: “I chanced at breakfast the other day, to wish I knew something of the biography of a shrimp.” Henry Morton Stanley, the adventurer who had gone to Africa to retrieve David Livingstone, told a swashbuckling story about doing that journey accompanied by Darwin, Herodotus, the Quran, the Talmud, The Thousand and One Nights, Homer, and much else. But as his porters left him or fell ill, he had to throw books away, until, he said, “I possessed only the Bible, Shakespeare, Carlyle’s ‘Sartor Resartus,’ Norie’s Navigation, and Nautical Almanac for 1877. Poor Shakespeare was afterwards burned by demand of the foolish people of Zinga.”

Working-class people themselves reflected on Arnold’s belief in fulfillment through reading and culture, and they diverged in their responses. Some feared that—as the radical author and former cotton-mill worker Ethel Carnie put it in a letter to the Cotton Factory Times in 1914—too much culture would “chloroform” working people, distracting them from the task of agitating to bring about real changes to their lives. For such readers, working-class people would do better to read Karl Marx, not Kongzi or shrimp biographies, and to turn to revolutionary political action to change their living conditions.

But others did not see any contradiction: they argued that reading and studying were the best way of opening one’s eyes to the exploitation going on in society and equipping oneself to fight against it—thus, not being chloroformed into sleep, but emerging into wakefulness. George W. Norris, a post office worker and union official who spent twenty-two years taking Workers’ Educational Association courses, looked back on the effect they had had on him, and wrote: “Training in the art of thinking has equipped me to see through the shams and humbug that lurk behind the sensational headlines of the modern newspapers, the oratorical outpourings of insincere party politicians and dictators, and the doctrinaire ideologies that stalk the world sowing hatred.”

And there was another factor involved. Studying, reading, looking at art, exercising one’s critical faculties: all these things could generate pleasure.

Humanists had always emphasized the hedonistic aspect of cultural life. Manetti had written of the enjoyment that came from thinking and reasoning. Cicero had argued for giving Roman citizenship to the poet Archias because of the pleasure as well as moral improvement he gave Romans. All three of our humanists in this chapter were in agreement that pursuing culture and developing one’s humanity to the utmost were deeply satisfying things to do. For Arnold, it brought life a taste of honey. In Mill’s case, personal experience of “the imaginations of poetry” and the study of “the ways of mankind” had given him back his ability to feel anything at all. Humboldt was the most blissed-out of the three, writing in a letter: “An important new book, a new theory, a new language appears to me as something that I have torn out of death’s darkness, makes me feel inexpressibly joyous.”

Inexpressible joy! To appreciate the difference between this sensibility and some of the narrow notions of culture that have held sway among duller pedagogues, it suffices to look at an ideology that briefly flourished in some American universities in the early twentieth century, known as “the New Humanism.”

That name for it came later, but the ideology was mostly the invention of Irving Babbitt, another Harvard scholar, though of a very different mentality from that of its president Charles Eliot. Babbitt argued for moral training based entirely on a monocultural canon: mainly the literature of the ancient Greeks, with perhaps a few Romans. Any other cultural sources were of no interest, and there was to be no talk of freedom in education. He began his polemical career with a published attack on Eliot’s educational philosophy; it appeared the year before the arrival of the Five-Foot Shelf. Such outreach projects, for Babbitt, were an abomination. In some ways he agreed with Arnold’s vision, but emphatically not in others: he had no wish to sweep the whole of humanity thitherward. For him, it did not matter whitherward the general public went. The humanist’s job was only to train an elite, who should be encouraged to have a “selective” and disciplined sympathy for others, tempered by judgment—not an empathetic free-for-all. We are not all connected by our humanity. Of Terence’s line “I consider nothing human alien to me,” Babbitt wrote that it was a mistake: it fails to be sufficiently selective. That line, for him, was responsible for the excess of weak-minded, wishy-washy do-goodery he saw everywhere around him in society. For him, and for the New Humanists who followed, the “best” was something to be shored up with ramparts and defended against outsiders.

Such ways of talking lose sight of everything that makes cultural life worthwhile for a genuine humanist: the ability to connect to others’ experiences, the free pursuit of curiosity, the deepening of appreciation. In particular, it loses joy, replacing it with compulsion—or a kind of accidia, if you will. When the novelist Sinclair Lewis (whose choice of the name Babbitt for one of his novels and its protagonist was surely a piece of deliberate mischief) won the Nobel Prize in 1930, he scolded the New Humanists in his acceptance speech. “In the new and vital and experimental land of America,” he said, “one would expect the teachers of literature to be less monastic, more human, than in the traditional shadows of old Europe.” Instead, what do we find? The old dryness and negativity.

Much later, Edward Said would observe in the context of another culture war that such a “sour pursing of the lips,” such a “withdrawal and exclusion,” and such disconnection of humanities from any concern with the “humane” produced a joylessness that no humanist such as Erasmus or Montaigne would recognize. Nor would a Humboldt, a Mill, or an Arnold, he might have added. Instead, as Montaigne wrote, speaking of the schools of his time:

How much more fittingly would their classes be strewn with flowers and leaves than with bloody stumps of birch rods! I would have portraits there of Joy and Gladness, and Flora and the Graces, as the philosopher Speusippus had in his school. Where their profit is, let their frolic be also.

This may seem a long-ago quarrel, and the New Humanists are mostly forgotten. Yet they have contributed to leaving a bad odor hovering around humanism, in some quarters. For some of those who now seek a diverse and more generous approach to culture, the very word humanism suggests a narrow elitism. Thus, if one ever sees humanism in academic life today being dismissed as conservative and opposed to the values of diversity and inclusion, some of the blame, at least, must go to the lack of humanitas in the New Humanists.

In fact, even as Irving Babbitt and his supporters were writing their polemics, they had lost their case. An explosion in access to reading, writing, and cultural life was already under way around the world. The cheap and popular books, the new circulating libraries that lent them to all and sundry, the courses accessible to anyone who wished to sign up: these were not going away.

Also, those lending libraries, cheap books, and courses provided a way for a large number of people to encounter some of the most radical of ideas to emerge in that century. For a few shillings, one could read skeptical investigations of God, works of Marxist economics, and scientific reevaluations of the origins of the Earth or of the living species to be found on it. You could read about human origins. All these fresh departures proceeded from what Arnold called “turning a stream of fresh and free thought upon our stock notions and habits.” And they, in turn, would take humanism itself down a new path.