12.

The Place to Be Happy

1933–now

Humanist organizations, manifestos, and campaigns—Born of Mary—courts, parliaments, and schools—Relax!—“glory enough”—enemies—architecture and city planning—Vasily Grossman—machines and consciousness—the posthuman and the transhuman—Arthur C. Clarke and the Overmind—the humanist bark—when, where, and how to be happy.

Also looking for Russell’s “world of free and happy human beings” throughout the twentieth century, and into the twenty-first, have been people who gather into groups under the name of Humanists. Some of these groups first developed out of Secular, or Rational, or Ethical Societies of the previous century. Some were strongly atheistic; others had links to quasi-religious organizations such as the Unitarians. Some mainly sought to promote scientific and rationalist ideas; others put more emphasis on moral living. Some were allied with radical socialism; others avoided political affiliation.

During the crisis of the 1930s it had occurred to a few people in America, mainly Unitarians, that it would be useful to make connections between groups by writing “some kind of humanist blast.” That blast became the world’s first Humanist Manifesto, issued in 1933. It presented humanism as a “religion,” partly because that was the Unitarian approach, and partly because it made a handy way to talk about a movement that otherwise fit no obvious category. Not all humanists wanted to be involved, in some cases because they disliked the idea of agreeing to any dogma at all. One of those invited to sign, Harold Buschman, wrote back warning, “There will be ‘heresies’ and misunderstandings instead of a free checking of experiences, one with another.” Another, F. C. S. Schiller, observed ironically, “I note that your manifesto has 15 articles, 50% more than the Ten Commandments.”

Thirty-four signatories did put their names to the manifesto. They thus endorsed a statement that showed concern with civil liberties and social justice, and a preference for reason as the best means of governing public affairs. Although the manifesto called humanism a religion, it also said that humanists see the universe as “self-existing and not created,” and that they expect no “supernatural or cosmic guarantees of human values.” A humanist may have “religious emotions,” but these mainly take the form of “a heightened sense of personal life and [a belief] in a cooperative effort to promote social well-being.” A humanist, they agreed, is a person whose field of concern “includes labor, art, science, philosophy, love, friendship, recreation—all that is in its degree expressive of intelligently satisfying human living.” In short, a humanist values “joy in living” and is someone to whom (to quote Terence) “nothing human is alien.”

This statement attracted strong responses from those whose idea of religion was quite different. The Bristol Press in Connecticut approvingly cited an anecdote of one student telling another, “Thomas, you say just once more that there is no God, and I will knock hell out of you.” The paper added, “Such a dose of medicine is the only argument which these professors are capable of understanding and in our humble opinion they would be cured.” In that fateful year of 1933, that was the least of the threats that would face humanists, “professors,” and everyone else besides.

In the postwar years, humanist organizations emerged, or old ones were revived, in many parts of the world. They included several notable groups in India—with its ancient freethought tradition going back to the Cārvāka school. The most flamboyant of the Indian activists was Manabendra Nath Roy, the founder of the Indian Radical Humanist Movement. In the earlier years of the century he had been a Marxist and spent time in Mexico helping with the foundation of the Communist Party there. He then spent eight years in the Soviet Union, once (as he recalled in his memoirs) cooking an excellent soup for Stalin. But he became disillusioned with Communism, especially in its Stalinist form, because of its lack of respect for individual lives or for personal freedom. Roy returned to India and became involved in the independence movement, spending six years in prison for his activities. (As Bertrand Russell remarked of the British at this time, they shared with Fascists the belief that one could “only govern by putting the best people in prison.”) He knew Mohandas K. Gandhi, but had some disagreements with his approach and formed a breakaway Radical Democratic Party. They differed as much in temperament as in political principle: Gandhi was known for his austere living, but Roy preferred the ebullient Robert Ingersoll tradition. For him, the humanist way of life meant appreciating the pleasures of this planet to the maximum: besides soup, he loved good food in general, as well as good wine, traveling, socializing, freedom, friendship, and “joy in living.” To promote these excellent things and his political commitment to internationalism and ethical living, he launched a “New Humanism”—definitely not to be confused with the elitist New Humanism of Irving Babbitt and his associates. Roy’s manifesto prominently featured Protagoras’s line: “Man must again be the measure of all things.”

Other Indian humanists were in the forefront of a new project after the war: the attempt to establish a unified body to support and coordinate the many groups around the world. A key mover came from the Netherlands: Jaap van Praag, cofounder in 1946 of the Dutch Humanist League. He was Jewish and had survived the war in hiding throughout the Nazi occupation. For him, promoting humanist values was one way of warding off the possibility of such things happening again. He and others organized a congress in Amsterdam in 1952 that convened more than two hundred delegates from all directions, brought together with the aim of founding a lasting institution and, naturally, writing a new manifesto to go with it.

As usual when humans get together with an important purpose in mind, the congress immediately fell to arguing strenuously over ideology and the choice of terms. According to an entertaining account by Hans van Deukeren, the disputes began with the question of what to call themselves. Some delegates wanted to make it an International Ethical Society; for them, “ethical” was a well-established general term for such groups, whereas “humanist” brought to mind Auguste Comte’s Religion of Humanity. Others were in favor of “humanist” and thought “ethical” was too bland. Only after fourteen hours of discussion did someone suggest calling it the International Humanist and Ethical Union. And so it became—IHEU for short—although it has now changed, to become Humanists International. It has continued to flourish, weathering further ideological disputes, and it remains the hub for the world’s humanists with their varied national challenges and battles.

As for the 1952 manifesto, known as the Amsterdam Declaration, this had an enduring success, but in evolving forms; it has been through several updates to add new ideas or adjust the emphasis of older ones. The latest version, issued by Humanists International in 2022, follows the 1952 original in many ways, above all by emphasizing the ethical focus of humanism. Both versions speak of the importance of personal fulfillment and development, as well as of social responsibilities and connections. Both support free scientific inquiry, informed by human values, as our best hope for finding solutions to our problems. Humanists, says the new version, in line with the original, “strive to be rational,” but artistic activity and “creative and ethical living” are also important. Both documents remind us of the long, inspiring traditions that lie behind modern humanism. Both also express a guarded optimism for the future. In the 2022 Declaration, this is summed up with the words: “We are confident that humanity has the potential to solve the problems that confront us, through free inquiry, science, sympathy, and imagination in the furtherance of peace and human flourishing.”

The 2022 version expands on all this, however, by including new elements that were missing in 1952. It puts more stress on the wide range of those humanistic traditions that nourish modern humanism: “Humanist beliefs and values are as old as civilization and have a history in most societies around the world.” Humanists, it says, hope for “the flourishing and fellowship of humanity in all its diversity and individuality.” Thus: “We reject all forms of racism and prejudice and the injustices that arise from them.” The 2022 Declaration follows the original in promoting the life-enhancing effects of arts, literature, and music, but also adds a mention of the “comradeship and achievement” to be found in physical activities. It shows a greater recognition of humanity’s connection and duties to the rest of life on Earth—“to all sentient beings,” as well as to future generations of humans. Finally, it sounds a new note of modesty in the closing section: “Humanists recognise that no one is infallible or omniscient, and that knowledge of the world and of humankind can be won only through a continuing process of observation, learning, and rethinking. For these reasons, we seek neither to avoid scrutiny nor to impose our view on all humanity. On the contrary, we are committed to the unfettered expression and exchange of ideas, and seek to cooperate with people of different beliefs who share our values, all in the cause of building a better world.” (To read the 2022 manifesto in its entirety, see the Appendix at this page.)

The evolving manifesto reflects changes in how humanists see themselves, as well as broader changes in the world: it provides more subtlety and respect for difference; there is no triumphalism when it talks of humanity. Adding these new levels of complexity has made for a longer text. But I like the new tone; I like the modesty and inclusiveness, alongside the older elements. Like earlier versions, the 2022 manifesto continues to ground humanism firmly in the realm of ethics and values, and the duty of care we all owe to one another and to our fellow living beings. All versions emphasize this more than matters of belief, irreligion, or even reason—important though those matters are. They focus less on religious doubt than on wider human questions of fulfillment, freedom, creativity, and responsibility. They make it clear that humanism is not primarily about carping at the faithful—an activity that can be alienating for many, and that is anyway not the most cheerful way of spending one’s time on Earth. (Carping at those in authority who insist on imposing their faith on others, on the other hand, seems to me an excellent way of spending one’s time.) Instead, this is a manifesto for something deeper: a joyful and positive set of human values.

This is also true of a 2003 manifesto issued by the American Humanist Association (founded in 1941, and glorying in the acronym AHA). It speaks of living life “well and fully,” guided by compassion as well as reason:

We aim for our fullest possible development and animate our lives with a deep sense of purpose, finding wonder and awe in the joys and beauties of human existence, its challenges and tragedies, and even in the inevitability and finality of death.

As humanist organizations work to become more positive and more approachable, they have also sought to build better connections with wider communities—including some that may have a high level of distrust or dislike of humanism. Religious institutions and beliefs can be central features of life in these communities, and often bring people a sense of social identity and shared meaning. If humanists are perceived mainly as anti-religious, they may be thought of as opposing the validity not just of specific beliefs but of the whole principle of meaning and identity. The Black American humanist Debbie Goddard has described running up against this perception when, as a college student, she openly declared herself an atheist. As she has said: “My closest black friends told me that humanism and atheism are harmful Eurocentric ideologies and implied that if I’m an atheist, I’m turning my back on my race.” Atheism was as seen as threatening “black identity and black history.” Goddard decided to work toward two goals: “getting more humanism in to the black community and more people of color into the humanist community.”

One of the things that modern humanist organizations—such as African Americans for Humanism, of which Goddard is now director—have tried to do is to emphasize how deeply Black and other perspectives enhance, inform, and enrich the humanist world, rather than being treated as something separate, supplementary, or distracting. In return, as a 2001 declaration by AAH stated, humanists can work more specifically to promote “eupraxophy”—“wisdom and good conduct through living”—in the Black American community. AAH is not the only U.S.-based organization for humanists of color; others include the Black Humanist Alliance and the Latinx Humanist Alliance, both affiliated with the American Humanist Association. In the UK, the Association of Black Humanists is similarly affiliated with Humanists UK.

Organizations for LGBTQ+ humanists also form part of larger humanist groups. The British version, LGBT Humanists, owes its foundation to an extraordinary case in 1977, when Christian fundamentalists resuscitated old blasphemy laws in order to prosecute the journal Gay News after it published a poem by James Kirkup, “The Love That Dares to Speak Its Name.”

The poem was certainly shocking to some Christians. It portrayed a Roman centurion kissing and caressing the crucified body of Jesus in a way that is at once sexual and tender. It caught the velociraptor eye of Mary Whitehouse, a conservative campaigner always on the lookout for more battles to fight—her previous ones had included trying, unsuccessfully, to get the BBC to ban the Chuck Berry song “My Ding-a-Ling.” Encountering Kirkup’s poem (presumably as she browsed innocently through her copy of Gay News), Whitehouse got to work organizing a criminal prosecution for blasphemous libel, not against the poet but against the journal and its editor, Denis Lemon.

The case, opening at the Old Bailey on July 4, attracted much interest; perhaps not as much as the Lady Chatterley’s Lover trial of 1960, but close. It was the first UK trial on a blasphemy charge in fifty-six years. The previous one had been brought in 1921 against the Bradford trouser salesman and freethinker John W. Gott, after he published a book called God and Gott; despite his fragile health, he was given nine months’ hard labor. Since then the law had not been used, but it was still officially in force.

Lemon and Gay News were defended, respectively, by two high-profile liberal barristers, John Mortimer and Geoffrey Robertson. Leading the prosecution case was John Smyth, who delivered a dramatic opening account of the offense the poem caused to those with Christian belief. After the case, he would rarely appear in the media again until, in 2017, he was obliged to leave the country after accusations of violent abuse of boys attending a Christian summer camp.

An obvious factor to consider in the trial would seem to be that of literary worth. Kirkup was a fellow of the Royal Society of Literature and a university tutor, so his credentials seemed good, and several noted writers offered to testify as to the poem’s quality. (The poet himself avoided getting involved in the case, later saying that he disapproved of any politicization of art.) But no literary testimony was heard, because the judge, Alan King-Hamilton, ruled it irrelevant. His summing-up to the jury at the end included remarks such as: “There are some who think permissiveness has gone far enough. There are others who may think that there should be no limit whatever to what may be published. If they are right, one may wonder what scurrilous profanity may next appear.” He would later recall that he felt “half conscious of being guided by some superhuman inspiration” while delivering this summation. On July 11, the jury duly brought in a ten-to-two guilty verdict. Both defendants were fined, and Lemon was also given a nine-month suspended sentence. The implication, as John Mortimer wrote afterward, was that making Anglicans blush was a criminal offense. And it was only Anglicans: other religions remained unprotected by the British blasphemy laws, as the British Muslim Action Front discovered in 1988, when it tried to use them against the publisher of Salman Rushdie’s The Satanic Verses.

Meanwhile, with all the publicity, and an excellent BBC docudrama based on the transcript, the main effect of the Gay News case was greatly to raise the profile both of LGBTQ+ rights and of the humanist cause. Mary Whitehouse had ranted about a “humanist gay lobby,” yet no such thing formally existed. Therefore, gay humanists decided to create one. In 1979 the Gay Humanist Group was born—later LGBT Humanists. In honor of its origin, they took the motto “Born of Mary.”

Fighting against blasphemy laws has continued to be a crucial part of what humanist organizations do. In some places the fight seems to be won, or nearly so: in the UK, blasphemy ceased to be a crime in England and Wales in 2008 and in Scotland in 2021, although at the time of this writing it remains illegal in Northern Ireland. In the United States, thanks to the First Amendment’s protection of freedoms of speech and belief, no such law ever existed on a national level, but a few do in individual states. The last conviction was almost a century ago: in Little Rock, Arkansas, in 1928, Charles Lee Smith received a prison sentence for displaying a sign reading “Evolution Is True. The Bible’s a Lie. God’s a Ghost.” At the first of his two trials, he could not even testify in his own defense, because, as a known atheist, he was not allowed to swear the necessary oath on the Bible to tell the truth.

A range of other countries have blasphemy laws on the books (in some cases inherited from British colonial laws), and seven currently go further by allowing for death sentences. An international “End Blasphemy Laws Now” campaign was founded in 2015, and the Center for Inquiry in the United States also created a “Secular Rescue” program. For those emerging from high-control religions and regimes, it offers help, including with asylum claims, immigration, legal needs, and scholarships. It has been described as an “Underground Railroad to save atheists.” During the period I have been writing this book, American humanists have also acquired new challenges to deal with in the United States itself, especially from the undoing—largely rooted in conservative religious views—of abortion rights that had once seemed firmly established.

All this lies at the most dramatic end of the activist spectrum, but organized humanists also keep busy working toward more modest achievements in their various countries: more inclusive and humanist-friendly treatment of religious subjects in schools, equal recognition of humanist wedding and funeral ceremonies, access to dignified assisted dying for terminally ill people, and so on.

In Britain, Humanists UK has some particular battles to fight, notably against the bizarre privileges still given to Anglicans in the political system—perhaps not surprising in a country with a long tradition of designating the monarch as “Defender of the Faith.” The House of Lords includes seats for twenty-six Church of England bishops, meaning that, in company with a handful of other theocracies, the UK automatically reserves a say in government for clerics. Both there and in the House of Commons, each day starts with prayers, usually led by a senior bishop (in the Lords) and a specially appointed Speaker’s Chaplain (in the Commons). Attendance is voluntary, but members who want to be sure of a place to sit on busy days find it advisable to reserve one for the prayer session; otherwise, they risk turning up later to find standing room only.

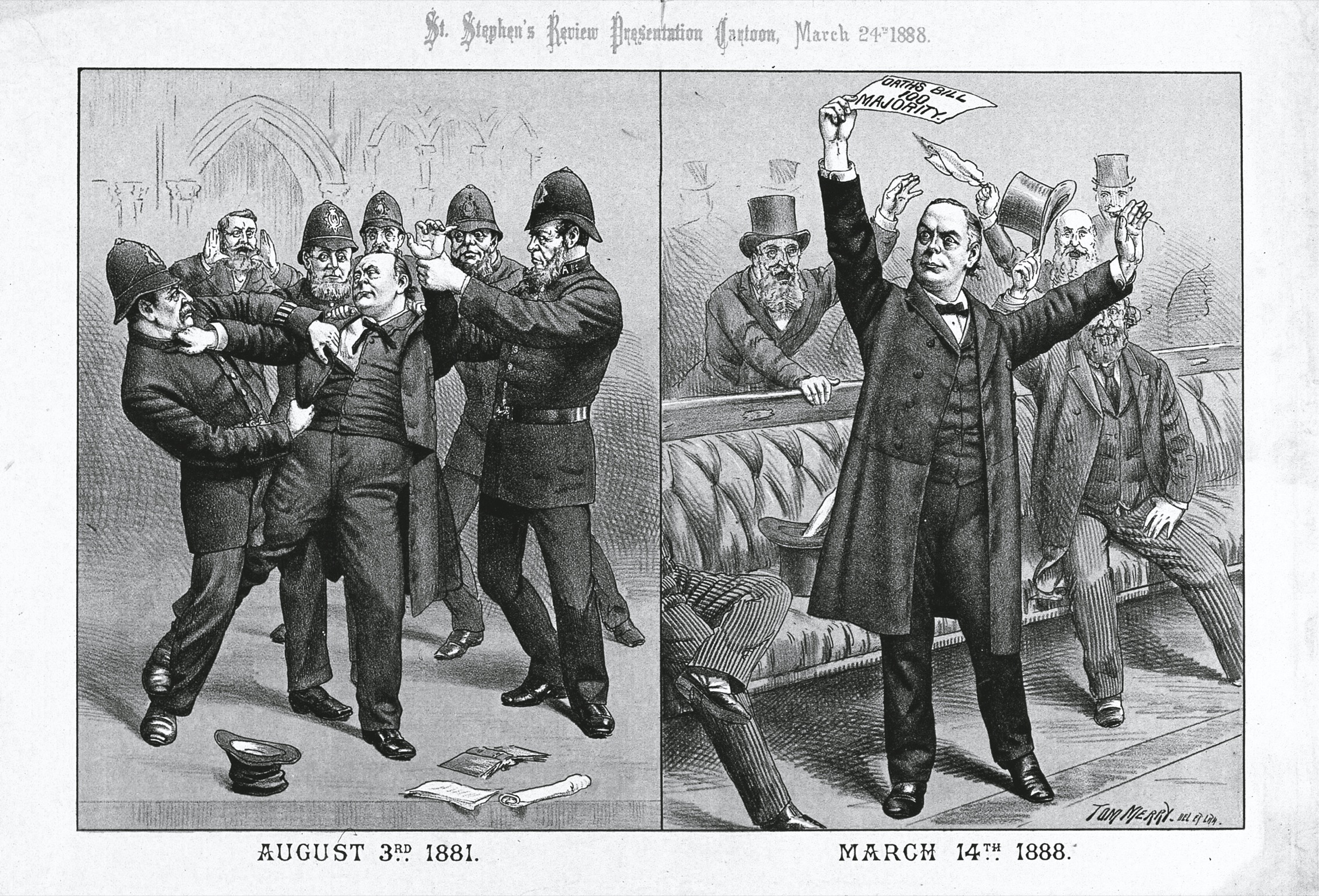

At least MPs no longer have to swear a specifically religious oath when they take office. The option to choose a secular affirmation was secured for them in 1888 by Charles Bradlaugh, MP and founder of the National Secular Society. Elected in 1880, he refused at first to swear the usual oath, and was not allowed to take up his seat. The theory, as always, was that non-believers could not be trusted to speak honestly in politics or do the right thing for the country, just as they could not be trusted to speak truly in court. As a paradoxical result, those without acceptable beliefs could prove their reliability only by lying. Bradlaugh offered to do that, giving the religious oath anyway. But now he was told he could not, since he had admitted to not believing in it. Each time he tried to enter Parliament he was ejected. Once he was held overnight in a cell underneath Big Ben, and another time he was forcibly bundled out of the building by security—not easy, as Bradlaugh was (like Robert Ingersoll) built on formidable dimensions. His friend George William Foote described his appearance on the street after his expulsion: there “he stood, a great mass of panting, valiant manhood, his features set like granite, and his eyes fixed upon the doorway before him. I never admired him more than at that moment. He was superb, sublime.” With Bradlaugh’s seat officially considered vacant, it kept going to by-elections, but he kept standing for it and winning again. At last, in 1886, he was allowed to take it up, making the standard religious oath—but soon after entering Parliament he proposed a bill to have the non-religious affirmation recognized instead. The bill passed and became law.

The United States also has religiosity woven into its political life, but in a different way. In contrast to the UK, it is officially secular, yet a strong assumption reigns that no (openly) irreligious candidate could ever attain high office. The older political foundations of the country were quite different: they were based on the principle of separation of church and state, and were in any case created by people who often had skeptical, deist, or pluralist beliefs themselves. Thomas Jefferson, for example, before creating his de-amphibologized Bible, wrote in his Notes on the State of Virginia that “it does me no injury for my neighbour to say there are twenty gods, or no god. It neither picks my pocket nor breaks my leg.” Some of the most conspicuous religious elements in the American public realm became established only in the 1950s. The phrase “under God” was added to the Pledge of Allegiance in 1954. “In God We Trust,” although used on coinage and elsewhere before that, began appearing on paper currency in 1957, following a law approved in 1956. Also in 1956, it replaced E pluribus unum as the motto of Congress.

Even during those pious postwar years, the United States’ secular principles meant that, in theory, children should never be obliged to attend religious lessons. In practice, this was often ignored. A quietly determined activist, Vashti McCollum, brought a case in 1948 against her son’s school for effectively making it impossible for him to avoid such classes. After repeated losses, she won at last at the Supreme Court. Along the path to that victory, she and her family endured much abuse. People threw rubbish at their door, including entire cabbage plants with roots and mud. Scrawled over both house and car windows was “ATHIST.” Letters arrived saying things like “May your rotten soul roast into hell.” When McCollum showed these letters to a woman who knocked at the door, hoping to persuade her to repent, the woman claimed that no Christian could have written such things. McCollum replied, “Well, it’s a cinch no atheist wrote them.”

In the UK, a similar outcry came in 1955 when the educational psychologist Margaret Knight delivered two BBC radio programs aimed at parents who wanted to teach their children moral principles without a Christian slant. She had to fight internal opposition within the BBC, and afterward the media rushed to deplore her. The Sunday Graphic printed her picture with the words, “She looks—doesn’t she—just like the typical housewife: cool, comfortable, harmless. But Mrs. Margaret Knight is a menace.” In a memoir, she recalled how, in her own youth, she had tried to suppress her religious doubts, until she read Bertrand Russell and realized that it was possible to say and feel such things. All she wanted to do with the radio series, she said, was to give parents and children a similar awareness that one could speak openly about matters of belief and doubt.

Raising such awareness still forms part of what humanist groups do today. Even if one lives in a society where non-religious views are widespread, generally, it can be hard to admit to doubts about a religion one has grown up personally embedded in. Humanist organizations hope to promote a general spirit of acceptance and even comfort, reminding people that if they do question their religion, they have company, and that living with a purely humanistic morality is a valid choice.

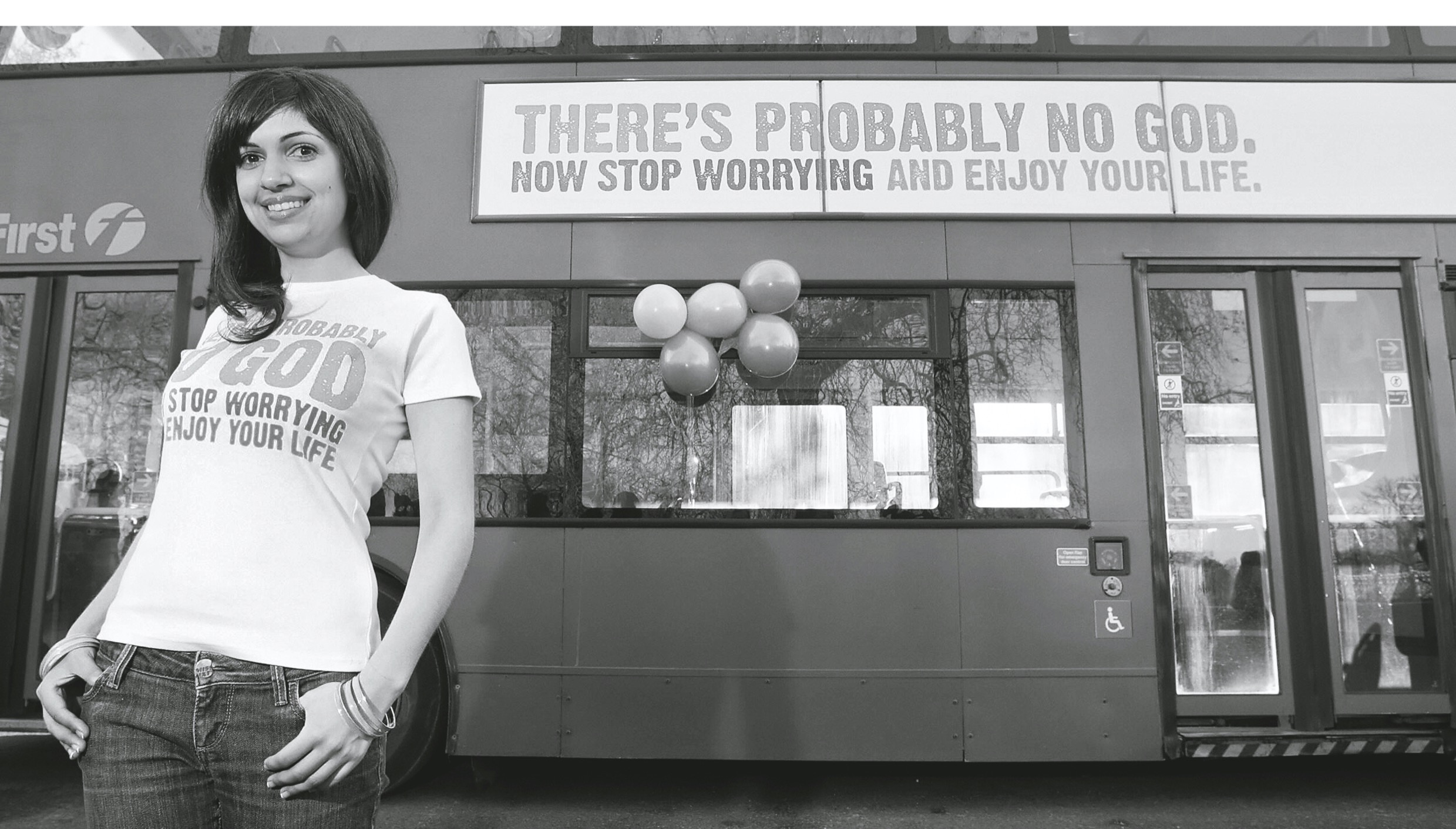

This was why both British and American organizations ran advertising campaigns in 2008 and 2009, putting posters on billboards and the sides of buses. The American Humanist Association’s messages read: “Don’t believe in God? You’re not alone.” And: “Why believe in a God? Just be good for goodness’ sake.” The British message, instigated by Ariane Sherine, was the one we met in our introductory chapter: “There’s probably no God. Now stop worrying and enjoy your life.” Not everyone liked that thought. Along with the more predictable letters of complaint received by the BHA from the religious were also some from hard-core atheists who thought the word probably was a cop-out, and from radical agnostics who felt that announcing even the probable nonexistence of God was too definite a statement to make. It goes to show that you can’t please all of the people all of the time—a good humanistic principle in itself.

The priority in these campaigns was, as always, to strike a positive note. Relax! Just be good—you have plenty of company—enjoy your life. The advertisements were meant not as attacks but as attempts to connect with people who might already be, to some extent, humanists without knowing it.

Meanwhile, religious practices and communities still offer many people joy, fellowship, and fulfillment. Why would humanists wish people not to have such (highly humanistic) forms of satisfaction in their lives? Indeed, most humanists do not wish this. They concentrate on helping those to whom religion has brought trouble or fear; they promote awareness of humanistic possibilities, and work for better laws and political structures to serve the needs of the non-religious.

Humanism should never mean taking anything away from the riches of human life; it should open up more riches. I am with Zora Neale Hurston, whose Democritan vision of material existence we met in the opening chapter. In the same passage, she also said:

I would not, by word or deed, attempt to deprive another of the consolation it affords. It is simply not for me. Somebody else may have my rapturous glance at the archangels. The springing of the yellow line of morning out of the misty deep of dawn, is glory enough for me.

My own sense of rapture and glory comes mostly from trying to imagine the grandeur and complexity of the universe, about which we are learning more all the time. Science tells us things that I can only describe as sublime: that we live in a universe estimated to contain some 125 billion galaxies, of which our galaxy alone contains some 100 billion stars, of which our particular star shines upon our planet and fills it with some 8.7 million diverse species of life, of which 1 species is able to study and marvel at such observations. That makes us a marvel, too: somehow, our three pounds or so of fleshy brain-substance are able to encompass and develop such knowledge, and to generate a whole mini-universe of consciousness, emotion, and self-reflection.

Atheists may find it simply perplexing that, given all this, so many people instead remain wedded to the idea of merely local gods who seem concerned mainly with collecting tributes and watching to see if we are having sex correctly. The question such atheists ask is: Why should not the human mental landscape reflect what we have managed to learn, so far, about the universe and its life and beauty—as if in a clear, undistorting mirror?

But very little of the human mental landscape is ever remotely like a reflection in a clear, undistorting mirror. Julian Huxley wrote of a human being as a transforming mill, “into which the world of brute reality is poured in all its rawness, to emerge . . . as a world of values.” We can try to make ourselves think as rationally and with as broad a scientific reach as possible; it is a good thing if we do. But we will also always live in a world of symbols, emotions, morals, words, and relationships. And that will often mean a porous border between non-religious and religious ways of relating to that world.

As the nineteenth-century Russian short-story writer, playwright, and physician Anton Chekhov wrote in 1889, in a letter to a friend—alluding to a song by Mikhail Glinka, with words by Alexander Pushkin:

If a man knows the theory of the circulatory system, he is rich. If he learns the history of religion and the song “I remember a Marvelous Moment” in addition, he is the richer, not the poorer, for it. We are consequently dealing entirely in pluses.

Dealing in pluses: that is glory enough for me.

But this does not mean that all is well. A more serious problem occurs not when supernatural beliefs are asserted but when deeper humanistic values come under threat, including in ways touched on throughout this book: cruelties to humans and other living things, the denial of respect to certain kinds of people, the preaching of intolerance, the burning or other destruction of “vanities,” and the suppression of freedom in thinking, writing, and publishing. In 1968, the doyen of British humanists, Harold J. Blackham, helpfully supplied a list of what he considered the “enemies” at that time—enemies being a word peaceable types are often reluctant to use, as he acknowledged. Nevertheless, he argued, it is necessary to recognize enemies. They are:

bigots, sectarians, dogmatists, fanatics, hypocrites, whether Christians or humanists, and all those, however labelled, who seek for any purpose whatever to dupe, enslave, manipulate, brain-wash, or otherwise deprive human beings of their self-dependence and responsibility, all those particularly who victimize thus the young and inexperienced. The humanist cause, in the vastest and vaguest of phrases, is “life and freedom,” and on the enemy front are all those doctrines, institutions, practices and people hostile to life or freedom.

We could add more for our own time: a whole breed of authoritarian, fundamentalist, illiberal, repressive, war-mongering, misogynistic, racist, homophobic, nationalist, and populist manipulators, some of whom claim devotion to traditional religious pieties, whether or not this is sincere. They show contempt for actual human lives yet promise—always!—something higher and better. As enemies of humanism, and of human well-being, they must be taken seriously.

On the other hand, they may also help us to answer the question “What is humanism?” We can find an answer by looking at the gaps left behind whenever a casual disregard of individuals is in the ascendant. Humanism is whatever should be there instead.

One can see this in specific areas of life, not just on a wide political canvas. For example: What is humanist architecture, or humanist city planning? It is the sort that does not constantly crush the ability to live a decent, satisfying human life. A humanistic civic designer pays attention to how people use a space and to what makes them comfortable, rather than trying to make a big impression with buildings of gasp-inducing size or a field of stylish obstacles that is frustrating to walk around. For humanistic architects, it is better to start with “the human measure.” Geoffrey Scott, author of the influential 1914 study The Architecture of Humanism, explained this by reminding us of our tendency to talk about buildings in terms of our own bodily experience, saying that they feel top-heavy, or soaring, or well balanced—descriptions derived from our own physical sense of existing in the world. A humanist architect will look for “physical conditions that are related to our own, for movements which are like those we enjoy, for resistances that resemble those that can support us, for a setting where we should be neither lost nor thwarted.”

These goals drove the great American advocate of humanistic city design, Jane Jacobs. She began by campaigning successfully in 1958 against a plan by Robert Moses to run an expressway right through the center of Lower Manhattan, demolishing Washington Square Park. She went on to write studies of how people actually live and work in cities—observing, for example, that it may seem a good idea to put large parks on the edge of town, but that people are more interested in walking through somewhere nice on their regular routes to work or the shops, rather than making special trips. She also noted that a bustling neighborhood street, filled with bars and frequented by unruly teenagers, may feel chaotic and noisy but is likely to be a safer environment than a clear open space—and certainly one more conducive to human relationships. The work of Jacobs influenced others, such as the Danish city planner Jan Gehl, who spent hours dawdling on Italian streets, taking notes about how the residents walked across a piazza or how they paused to chat while leaning on a bollard. A local paper printed a picture of him at lurk, with the caption “He looks like a ‘beatnik,’ but he isn’t.” Then he applied his discoveries to projects around the world, working with local citizens. In one case, after he and residents of the Danish housing project of Høje Gladsaxe had jointly designed a children’s play area, the original architects called the results “an act of vandalism against the architecture.” For Gehl, that always made more sense than architecture vandalizing people’s lives.

What applies in urban design applies in many other fields as well—politics, certainly, but also aspects of medical practice and the arts. Anton Chekhov, whose thoughts on “pluses” we met a few pages ago, took this human-first approach in his work both as a physician and as a writer. His short stories, especially, are humanistic in the close attention they pay to the events (or quiet non-events) from people’s everyday lives: moments of love or heartbreak, journeys, deaths, boring days. His views on religion and morality were also those of a humanist: he disliked dogma and was skeptical about supernatural beliefs. As one twentieth-century admirer of Chekhov wrote:

He said—and no one had said this before, not even Tolstoy—that first and foremost we are all of us human beings. Do you understand? Human beings! He said something no one in Russia had ever said. He said that first of all we are human beings—and only secondly are we bishops, Russians, shopkeepers, Tartars, workers. . . . Chekhov said: let’s put God—and all these grand progressive ideas—to one side. Let’s begin with man; let’s be kind and attentive to the individual man.

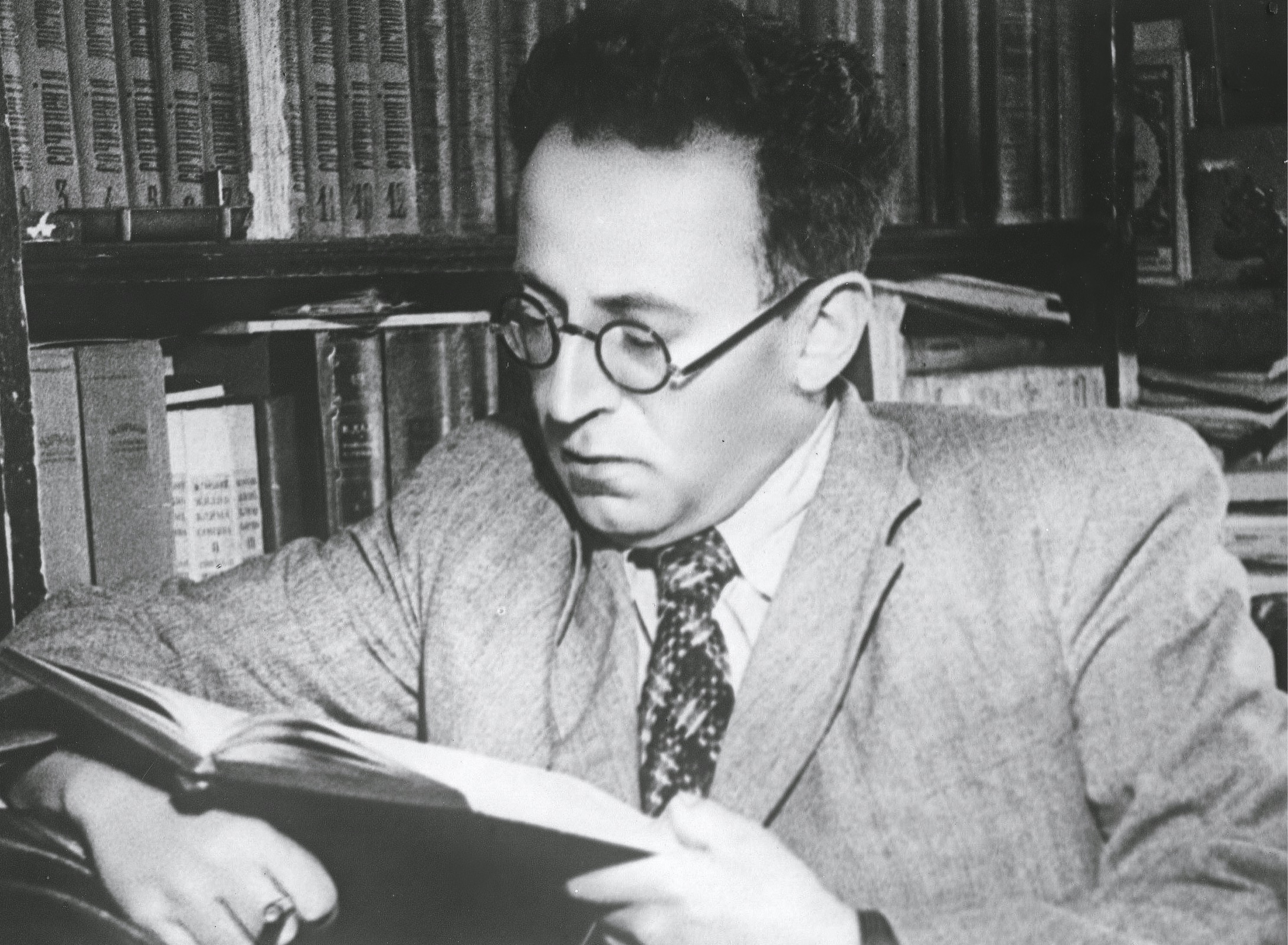

These words are actually spoken by a fictional character, in a scene from the novel Life and Fate by the Jewish Ukrainian writer Vasily Grossman, another of the great humanist authors. Like Chekhov, Grossman was a scientist as well as a creative writer: he began in a career as a chemical engineer. Then he took up writing fiction, much of it light and comic at first, and journalism during the Second World War, especially by filing reports from the battle front at Stalingrad. In the 1950s, he worked on Life and Fate, which was much influenced by his war experience and especially by the loss of his mother, Yekaterina Savelievna, who was murdered by the Nazis. Life and Fate plunges us into the very worst that the twentieth century had to offer: war, mass murder, cold, hunger, betrayal, racist persecution in both Nazi-occupied territory and the Soviet Union—in short, human grief and suffering on a staggering scale. It takes us to places we can hardly bear to go, including into a Nazi gas chamber and right into the moment of death. But through all of this, Grossman imbues the narrative with his humanist sensibility, putting individuals at the center, never ideas or ideals.

He was a humanist in other ways, too. He did not like religious institutions, which he saw as tending to obstruct rather than encourage people’s natural tendency toward kindness and fellow feeling. For Grossman, those two qualities were all that really mattered. As another character in Life and Fate says, “This kindness, this stupid kindness, is what is most truly human in a human being. It is what sets man apart, the highest achievement of his soul. No, it says, life is not evil!”

In a Communist regime, it was fine to criticize the ideologies of traditional religion, but not those of the state. Grossman particularly courted disfavor by exposing the Soviet Union’s own anti-Semitic tendencies, which were not acknowledged to exist. When he began Life and Fate, Stalin was still alive and there seemed little likelihood that such a book could be published. But in 1953, Stalin died and was succeeded by Nikita Khrushchev, who promised a cultural “thaw.” So by the time Grossman finished the novel in 1960, it seemed to him that it was worth sending it to a publisher, after all. Friends warned him that he was being too optimistic; they were right. Soon after he dispatched it, he received a visit from the KGB. They searched his house and removed other copies of the typescript, along with all his drafts and notebooks. They also took carbon paper and typewriter ribbons, wanting to obliterate even those faint imprinted ghosts of the words. The book seemed to have been wiped from the Earth.

What they did not know was that Grossman had taken the precaution of giving two other versions to two different friends, who hid them and waited. Grossman wrote other books, including an unfinished novel about the confused emotions of a man emerging from a thirty-year imprisonment in the Gulag, and a beautiful account of his own travels and encounters in Armenia. By that time, he was ill with stomach cancer. He died in 1964, still seeing no prospect of getting Life and Fate published.

More than a decade went by. Then, in 1975, one of the friends managed, with help from others, to smuggle a microfilm of the manuscript out of the country. The film was hard to read, but further copies were made, and a partial version of the text appeared from a publisher in Switzerland in 1980. Five years later, a more complete version came out in English translation. It was immediately hailed as a twentieth-century masterwork, comparable to Tolstoy’s War and Peace—or to an interlinked series of Chekhov stories. Part of its fascination was its own story; one of survival against the odds. Like so many works by our humanists in earlier times, it had been saved by ingenuity, concealment, rescue, and reduplication. And, as Petrarch and Boccaccio and the early humanist printers knew, nothing is so good for rescuing a book as making lots of copies of it.

There are certainly lots of copies of Life and Fate around today. If someone asks you “What is humanism?” and a more direct answer does not come to mind, you could do worse than taking that person to a bookshop and buying them one.

Every time a person dies, writes Grossman in Life and Fate, the entire world that has been built in that individual’s consciousness dies as well: “The stars have disappeared from the night sky; the Milky Way has vanished; the sun has gone out . . . flowers have lost their colour and fragrance; bread has vanished; water has vanished.” Elsewhere in the book, he writes that one day we may engineer a machine that can have humanlike experiences; but if we do, it will have to be enormous—so vast is this space of consciousness, even within the most “average, inconspicuous human being.”

And, he adds, “Fascism annihilated tens of millions of people.”

Trying to think those two thoughts together is a near-impossible feat, even for the immense capacities of our consciousness. But will machine minds ever acquire anything like our ability to have such thoughts, in all their seriousness and depth? Or to reflect morally on events, or to equal our artistic and imaginative reach? Some think that this question distracts us from a more urgent one: we should be asking what our close relationship with our machines is doing to us. Jaron Lanier, himself a pioneer of computer technology, warns in You Are Not a Gadget that we are allowing ourselves to become ever more algorithmic and quantifiable, because this makes us easier for computers to deal with. Education, for example, becomes less about the unfolding of humanity, which cannot be measured in units, and more about tick boxes. John Stuart Mill’s feeling of being fully “alive” and “human” as one comes of age; Arnold’s sweetness and light; Humboldt’s “inexpressibly joyous” experience of intellectual discovery—these turn into a five-star system for recording consumer satisfaction. Says Lanier: “We have repeatedly demonstrated our species’ bottomless ability to lower our standards to make information technology look good.”

To see this demeaning thought taken to its logical conclusion, we can turn back by more than a century to—surprisingly—George Eliot. Not normally known as a science fiction writer (or, indeed, as a pessimist), she came up with a terrifyingly pessimistic sci-fi image in her final book, Impressions of Theophrastus Such, published in 1879. A character in the chapter “Shadows of the Coming Race” speculates that machines of the future might learn to reproduce themselves. Having done so, they might also then realize that they do not need human minds around them at all. They are able to become all the more powerful “for not carrying the futile cargo of a consciousness screeching irrelevantly, like a fowl tied head downmost to the saddle of a swift horseman.” And that is the end of us.

Oh well. These days some think that, if humanity ends in disaster, caused by rogue artificial intelligence or environmental collapse or some other blunder, the world would be better off without us anyway. We are hardly a good influence: we are wrecking the planet’s climate and ecosystems, obliterating species with our crops and livestock, and redirecting every resource to the production of more and more humanity. Even our satellites proliferate like a rash over the night sky. Our impact is so great that geologists are debating the possibility of officially designating our epoch the Anthropocene, a period that may be identifiable in the sediment, in part, by a layer of our domesticated chicken bones. That puts the screeching fowl of consciousness in a new light. But if we do humanize everything, in the end we will consume the basis for our own lives, too, and thus dehumanize everything again.

Contemplating this, some human beings seek paradoxical consolation by embracing the prospect. “Posthumanists,” as they are sometimes known, look forward to a time when human life is either drastically reduced in scope or no longer around at all. Some propose deliberately bringing about this self-destruction ourselves. That is the message of the Voluntary Human Extinction Movement (VHEMT), founded in 1991 by environmentalist and teacher Les U. Knight. Half serious and half a surreal work of art, the movement advocates doing the Earth a favor by giving up breeding and waiting for ourselves to gently fade away.

Posthumanism has a benign air of modesty about it, yet it is also a form of anti-humanism. Somewhere at the heart of it, I think, is an old-fashioned sense of sin. The desire is to imagine the Earth returned to an Edenic state, with humanity not just expelled from the garden but actually uncreated. It is not all that remote from the idea of a few extreme Christians that we should accept (or even accelerate) the environmental crisis on Earth, because it will bring Judgment Day all the sooner. In a 2016 survey, 11 percent of Americans endorsed the statement that, with the end times coming anyway, we need not worry about tackling the climate challenge. More puzzlingly, 2 percent of those identifying as “agnostics or atheists” agreed with it, too.

Others devoutly wish for a different consummation. “Transhumanists,” unlike posthumanists, look forward eagerly to technologies that will, first, extend the human lifespan considerably, and, later, allow our minds to be uploaded into other data-based forms, so that we can ditch the need for human embodiment. Some talk of a moment of “singularity,” when the rate of development has accelerated to the point that our machines and ourselves may fuse into one. In the stage after that, as Ray Kurzweil writes in The Singularity Is Near, “vastly expanded human intelligence (predominantly nonbiological) spreads through the universe.”

Posthumanism and transhumanism are opposites: one eliminates human consciousness, while the other suffuses it into everything. But they are the sort of opposites that meet at the extremes. Both agree that our current humanity is something transitional or wrong—something to be left behind. Instead of dealing with ourselves as we are, both imagine us altered in some dramatic way: either made more humble and virtuous in a new Eden, or retired from existence, or inflated to a level that sounds like that of gods.

I am a humanist; I cannot happily contemplate any of these alternatives. As a science fiction enthusiast, I used to have a weakness for transhumanism, however. Years ago, my mind was blown by a classic science fiction novel: Arthur C. Clarke’s Childhood’s End, published in 1953.

The story begins, as many in the genre do, with aliens arriving on Earth. They promptly shower us with gifts, which include hours of entertainment. “Do you realize that every day something like five hundred hours of radio and TV pour out over the various channels?” asks one character in the book, conveying 1953’s idea of a cornucopian abundance. But the bounty of the aliens comes with conditions: humans must stay on Earth and give up exploring space.

A few people resist the gilded cage, declining to watch the entertainment and proclaiming defiant pride in human achievements. But as time goes on, this aging minority is forgotten and a new generation emerges. They have new mental gifts, including the first stirrings of an ability to access the “Overmind,” a mysterious shared consciousness in the universe, which has outgrown “the tyranny of matter.”

That generation in turn gives way to the next, and these beings are hardly human at all. Needing no food, having no language, they simply dance for years, in forests and meadows. Finally they stop and stand motionless for a long time. Then they slowly dissolve upward, into the Overmind. The planet itself becomes translucent like glass and shimmers out of existence. Humanity and the Earth have gone, or rather, they have been transfigured and merged into a higher realm.

Such an ending for humanity is neither optimistic nor pessimistic, writes Clarke; it is just final. So is his novel, in a way. It pushes fiction to its limits. Earlier science fiction writers had also imagined a future in which humanity dies, notably Olaf Stapledon in his 1930 work, Last and First Men. But Clarke goes further, into a realm where there can be no more stories at all. Species have vanished; even matter has vanished, at least from Earth. He goes where Dante went in his Paradiso—and Dante complained in that work’s first canto that this necessarily defeats the powers of any writer. To write about Heaven is “to go beyond the human”—transumanar—and, says Dante, this also means going beyond what language itself can accomplish.

When I first read Childhood’s End, I loved its finale. Now I feel the melancholy of such a vision far more. It leaves me in mourning for those flawed, recognizable individuals that we are and for the details of our planet and our many cultures, all lost to a universal blandness. Every particularity has gone: the atoms of Democritus, Terence’s nosy neighbor, Petrarch’s lack of patience and Boccaccio’s bawdy stories, the Lake Nemi ships and the fishlike Genoese divers, Aldus Manutius and his exuberance (“Aldus is here!”), students floating down rivers, Platina’s recipe for grilled eel à l’orange, Erasmus’s polite farts, the Encyclopédie (all 71,818 articles of it), Hume’s games of backgammon and whist, Dorothy L. Sayers’s comfortable trousers, Frederick Douglass’s magnificently photographed face and his eloquent words, the priestly and poetic Kawi language, sea squirts, bloomers, the Esperanto plaque by Petrarch’s beloved stream, M. N. Roy’s good soups, ridiculous heraldry, Rabindranath Tagore’s classes under the trees, the windows of Chartres, microfilms, manifestos, meetings, Pugwash, busy New York streets, the yellow line of morning. They have all gone up in the ultimate bonfire of the vanities. To me, this no longer says sublimity; it says, “How disappointing.”

Where, in all this pure divinity and mysticism, is the richness of actual life? Also, where is our sense of responsibility for managing our occupancy of Earth? (Not that Clarke himself supported abdicating such responsibilities—quite the contrary.) And what about our relationships with fellow humans and other creatures—that great foundation for humanist ethics, identity, and meaning?

These dreams of elevation perhaps emerge from memories of being a small child, lifted out of a cradle by big arms. But the Earth is not a cradle; we are not alone here, since we share it with so many other living beings; and we need not wait to be spirited away. Give me, instead of the Overmind, or the sublime visions of any religion, these words of a more human wisdom by James Baldwin:

One is responsible to life. It is the small beacon in that terrifying darkness from which we come and to which we shall return. One must negotiate this passage as nobly as possible, for the sake of those who are coming after us.

A sense of sin is of no help on that journey; neither is a dream of transcendence. Dante was right: we really cannot transumanar, and if we have fun trying—well, that can produce beautiful literature. But it is still human literature.

I prefer the humanist combination of freethinking, inquiry, and hope. And, as the late scholar of humanism and ethics Tzvetan Todorov once remarked in an interview:

Humanism is a frail craft indeed to choose for setting sail around the world! A frail craft that can do no more than transport us to frail happiness. But, to me, the other solutions seem either conceived for a race of superheroes, which we are not . . . or heavily laden with illusions, with promises that will never be kept. I trust the humanist bark more.

Finally, as always, I am brought back to the creed of Robert G. Ingersoll:

Happiness is the only good.

The time to be happy is now.

The place to be happy is here.

The way to be happy is to make others so.

It sounds simple; it sounds easy. But it will take all the ingenuity we can muster.