Resisting reruns of SpongeBob SquarePants while revising; avoiding the shark-like gaze of your cruel, capricious maths teacher; trying to think of something hilarious-but-alluring to say to that person you’re dying to snog – your school years are pretty tough. As if all that wasn’t hard enough, the average age at which people usually ‘come out’ as gay, lesbian or bi is now seventeen years old – while still at school or college. Just one more thing to worry about, and it’s not on the curriculum.

How to do it? When to do it? Whom to tell? To tell at all? Coming out is a potential minefield. One wrong step and your metaphorical gay leg will be blown clean off.

Seriously, though. For a young LGBT* person, there is NOTHING more terrifying than the idea of telling your nearest and dearest that you fancy people with the same bits as you or that you’ve pretty much had enough of your original gender. This fear is perfectly reasonable, but there are ways in which we can make the transition from ‘closet case’ to ‘out and proud’ as smooth as caramel.

In the olden days (and to this very day in some rather traditional quarters), fancy young society women, known as debutantes, were dressed up and paraded around for potential suitors and the like. These events were known as ‘coming out parties’, and this is where we get the term ‘coming out’. Before the First World War, the phrase meant more to ‘come out’ into society.

These days, we refer in particular to ‘coming out of the closet’, an American slang term for no longer concealing one’s identity. Once you’re ready to let the world know about your identity, you are no longer ‘closeted’ or ‘on the down-low’.

The word ‘identity’ is key. ‘Coming out’ isn’t when you first swap love juice with someone of your own gender, but rather the public adoption of a label. It’s telling people.

As I’ve said numerous times, labels aren’t for everyone. Lots of people may choose to have sexyfuntimes with people of the same gender without identifying as gay or lesbian, just as a gay man who has sex with a woman isn’t automatically straight. (‘Hallelu! He’s seen the light!’ Yeah, that’s not gonna happen). The process of establishing an identity can take years. The good news is, no one is stuck with one label for their whole life. Many people change their sexual identity as they become more comfortable with themselves and their sex lives.

The same is true of gender labels. Gender doesn’t have to be concrete.

One only has to look at the thriving queer club scene to see hot young things experimenting with traditional gender roles. These have nothing to do with sexuality, as we’ve discussed.

At its core, ‘coming out’ is the part where you tell someone what your sexual or gender orientation is – and that can be anything.

Perhaps the real question is: is there any benefit to coming out? The answer is almost certainly …

People cheerfully profess their religion, marital status, ethnic origin and favourite food, but discussion of sexual orientation or gender remains uniquely taboo. Perhaps with good reason.

As we have learned, there are eighty countries where men and women can be prosecuted for having sex with someone of the same gender. MEGA POLITICAL SADFACE.

If it is safe to ‘come out’, however, there are many benefits to doing so. At the end of the day, desires, crushes, dating and relationships are a massive part of anyone’s life, and hiding something so vital from your friends and family is both hard work and isolating. It may sound trite, but ‘being yourself’ is good for you. Sharing is caring, yo!

‘For me, the main benefit was a general sense of ease – I no longer had to hide where I was going, why I had the letters “G-A-Y” stamped on my wrist or the uncomfortable feelings when asked why I didn’t have a boyfriend or what kind of boys I liked.’

Mica, 23, London.

The single phrase mentioned time after time after time in the survey was ‘a weight off my shoulders’. So cliché, but so, so true.

On a more practical level, once a young person has ‘come out’ as gay, lesbian, bisexual or trans, it is that much easier to find like-minded people. Allsorts Youth Project, just one example of an LGBT* group for young people in Brighton, has a weekly club night where young people can socialise in a safe space – without the need for gay bars or clubs. (More on that in chapter 8.)

Furthermore, once a person chooses to identify as gay, lesbian, bisexual or trans, you’d be surprised at how supportive family and friends can be. Very often, parents and friends have already worked it out, and ‘coming out’ leads to a closer, more honest relationship with the people you love the most. Perhaps best of all, they’ll stop trying to fix you up with people who are the wrong sex!

Finally, don’t underestimate the personal satisfaction and pride you’ll feel at simply being yourself. It’s freeing.

‘There are so many [advantages to coming out] that it’s hard to know where to start. The main things are to know that you will still be loved, and that you are happy and contented in who you really are. I was so worried about how my family would react to my sexuality that it used to keep me awake at night … now I know how well [coming out to them] went, I wish that I had talked to them sooner. It took a few months to adjust to being open about my sexuality, but it definitely made me closer to my family. I did run into some issues with bullying at school, being the first boy to “come out”. Once I was accepted (begrudgingly) as a part of the school, I think it was easier for others to be honest. I was very lucky in that I had some good teachers, lots of friends and my family for support.’

Mike, UK.

Of course, there may be good reasons why people choose not to discuss their sexual or gender identity. For one, it does often seem that there are three choices – straight, gay or bi. Sometimes it’s just not that simple, so defining yourself may take more time.

Moreover, some communities and religions believe that homosexuality is wrong. That doesn’t prevent anyone from being lesbian, gay or bisexual but rather restricts their ability to be ‘out’, as this may mean they feel their parents and friends might not be supportive of them.

The worry of what family and friends might think or do is what keeps people in ‘the closet’ more than any other factor, regardless of background. Remember, every ‘out’ gay or bisexual man or woman and every ‘out’ trans person has gone through this process and survived the ordeal. Most retain the family and friends they had before they ‘came out’.

The fear that you’ll be disowned, shamed and tossed out onto the street is absolutely the worst-case scenario and one that very rarely happens. There may be friends who are unable to accept your new identity, and that’s sad, but you can always make new friends. The worst fear is that your family, especially your parents, might react badly. At first many do – I won’t lie – but with time, nearly all build a bridge and get over it.

If (and I can’t stress how rare this is) the situation becomes so bad that you have to leave home, there is support out there. Some people live with other family members or family friends. Alternatively, Young People’s services will be able to refer you to the right people who can help you. There’s a list of groups near you at the back of the book.

‘It started when my mum saw me hugging a friend on Facebook. She is Catholic – very Catholic – and for months I was getting, “You’re gay – I’m gonna kick you out”. After about two months of this, something in my head snapped and I said, “I’m not gay, I don’t know what I am!” I was fourteen. Two days later I got kicked out. I had to work … I worked in a Chinese takeaway. Eventually I became a chef, and now I own my home.’

Shane, 23, Shoreham-By-Sea.

So you’ve decided you might identify as LGBT*? The hardest part – admitting it to yourself – is done. But how to tell everyone else?

I decided it was time to come out about six months after my Dean Cain–based revelation. I told a very close friend whom I trusted not to write it on the sixth-form common room noticeboard. She had also done a very good job of signalling to me that she was A-OK with THE GAYS. As a young questioning person, you would do well to surround yourself with cool, open-minded people – it lubes the passage out of the closet, as it were.

I chose to tell her – well, ‘chose’ isn’t the right word; rather it popped out as I carried a treacle tart home from school one day. (I stress I had made the tart earlier in a home economics class. I don’t just carry cakes around to make people like me.)

Predictably, my friend was cool and reassuring and herself came out as queer in the same conversation, so I felt a million times better. To this day, though, I cannot eat treacle tart without feeling like my world might come crashing in around me, as it did that night after I had come out – because even though my afternoon had been perfectly pleasant, the cat was now out of the bag, and I couldn’t get the furry bugger back in it. That is always going to be scary.

I adjusted quickly. Over the following weeks, I talked about boys CONSTANTLY, making up for lost time, and within a few weeks I was happily telling my friend and a couple of other friends which boy I’d most like to snog on the rugby team. It was all fine and I haven’t looked back.

I came out to my parents much later – I waited until I was living away from home and able to support myself financially. You can decide if that was cowardly or sensible. In the end, my mum actually asked me outright and I answered her honestly. I got my stepmum to tell my dad!

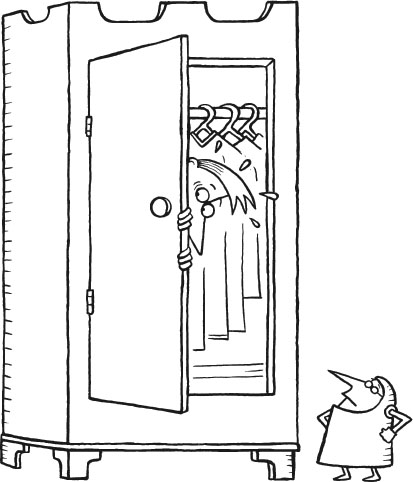

Every LGBT* person’s experiences are different, but here are the dos and don’ts of coming out:

Every ‘out’ gay or bisexual or trans man or woman has been through it all before!

‘I first told my then boyfriend. We’d only been going out about a fortnight, and he came out as transvestite to me as we were curled up in bed together, so it only seemed right that I told him I was bi.’

Sarah, 35, Ireland.

‘I told my friend in the tiny music practice room in our school. It amuses me today to think that most people come OUT of the closet. I came out IN a closet. I thought I was bisexual at first, although, in retrospect, I think that I was having difficulty understanding the difference between the strong kinship I felt with my female friends and the sexual attraction I had to other boys. It felt like a large part of puberty was finding out the answer to this conundrum.’

Rick, 29, UK.

‘[I came out on a] residential trip to France. My gay friend asked me how I felt about her being gay, and I said I was OK. She asked me if I was straight. I said no. We carried on talking about how sh*t the French weather was when you had to do an assault course in the mud.’

Nina, 16, UK.

‘[I first told] People at my halls of residence at uni. We went on a night out just before Christmas, and I made sure they were all there and told them one by one. The first was someone I had gotten really close to, and after that, admittedly with a drink or two inside me, it got easier.’

Chris, Manchester.

‘I first told a girl I was friends with at school. I was sixteen and we were at a party, and we went for a long walk and had a deep and meaningful. She told me she was in love with another one of our friends, and I said I really fancied our art teacher.’

L, 28, Brighton.

Of course … it’s not always so smooth. Coming out can be tough.

‘I told my girlfriend at the time, whom I’d been with for three years, about my thoughts and feelings regarding my desire to transition to female, my self-view as female and my experimentation over the past number of years. She broke up with me then and there, refusing to discuss it.’

Laura, 21, UK.

‘The first person I told was a female friend who believed she was in love with me. She was married and had made it clear that she was prepared to abandon that to be with me. I felt like I owed it to her to explain why that could never happen.’

BFL, 43, Minnesota, USA.

‘My stepmum discovered photos from the Internet that I had printed at college … It kind of went from there!’

Dani, 29, Newcastle upon Tyne.

Friends are relatively easy to come out to, as you’ve (presumably) picked mates who aren’t total douches. Some LGBT* people are in heterosexual or cisgender relationships when they figure it out, and it can be very hard to tell a partner that you’re not (exclusively) sexually interested in them.

But most LGBT* people worry the most about telling their parents. It really scares the plop out of us. Why? Well, they knew us as babies, and coming out (as gay, bi or lesbian) is essentially offering a delightful insight into your sexual desires.

Something NO ONE enjoys saying: ‘Hey, Mum, you’ll never guess what I like having up my bum!’ See my point?

For trans people, some parents see it as a bit of a slap in the face. Like they GAVE you your assigned gender and they RAISED you accordingly. As with sexuality, though, it often comes as no surprise, and many parents can be hugely supportive of transgender children – even very young ones. There are support groups, such as MERMAIDS, for parents of trans children (see ‘Helpful numbers and websites and stuff’ at the back of the book).

Coming out is as personal as your identity. The following is only a guide – a one-size-fits all approach for you to adapt.

1. Pick your time

It might be spontaneous, or you might plan a specific time (although the build-up would be TORTURE). A lot of LGBT* people seem to use the TV as a prompt; i.e. bringing it up when gay rights are mentioned in the news or when gay couples are shown in soaps (which is pretty much every day). Whatever time you pick, I think a 1-2-1 conversation is always best.

2. Pick a venue

Remember, your loved ones might need a bit of time to process, so I wouldn’t recommend a Topshop changing room. Nine times out of ten, home is best, or at the very least an establishment that serves tea. Tea makes everything OK – remember that. (Do you have somewhere to go if they need some space – could you pop round to a mate’s house?)

3. Is it safe?

Your safety is more important than anything else on earth. Do you live in Saudi Arabia or one of the eighty-ish countries (see chapter 6) where you might be locked up or stoned to death? Look into getting a passport.

Joking aside, if your parents have expressed homophobic sentiments in the past, it may be wise to make a plan B should they react badly. A lot of people choose to wait until they have a degree of independence before taking this step. Make contact with gay youth groups – a list of which are at the back of this book – and ensure you have support should things go awry.

OK, so now we’ve set it all up, here are some openers:

‘I really wanted to talk to you about something …’

Now, at this stage, it’s possible your parent(s) might say, ‘Is this about your being gay?’ VERY OFTEN parents have got an inkling. This is exactly how my mum dragged me out of the closet.

If they don’t, however …

‘For a while now, I’ve been attracted to men/women/men AND women’ or ‘I identify much more as a guy than I do a girl’ (or vice versa).

Then …

‘Nothing’s changed. I’m still exactly the same person you know, and I hated keeping that a secret from you.’

And then give them a chance to reply. You might be surprised and delighted.

‘I told my parents I was bisexual at twenty. They were conservatively religious, but they told me they loved me just the same. I told them I was actually gay shortly after turning twenty-two, and this time they didn’t bat an eyelid.’

Stephen, 22, Johannesburg, South Africa.

‘I told them both, although separately, as they are divorced, and each one was in a pub while we were having dinner. They were a little taken aback, but after a while, I think after they had thought about it for a bit, they realised that it explained a lot of my previous behaviour and appearance. They couldn’t care less now and are happy that I am happy.’

Jools, 38, Madrid, Spain.

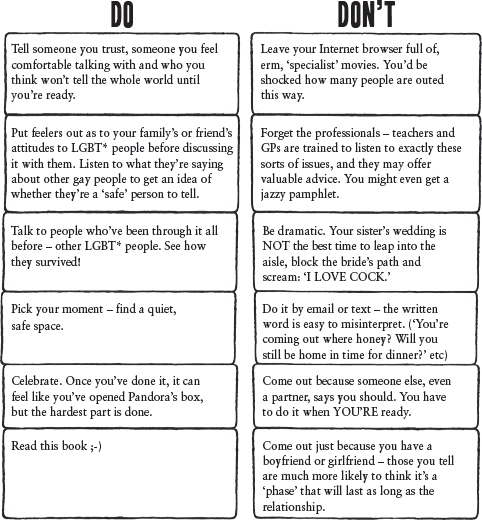

But what if they’re not happy? Some likely objections:

Keep strong and listen to Lady Gaga’s Born this Way. Or simply present them with this very book and get them to turn to this chapter!

After you’ve told them, back off. You’re not going to pester anyone into being fine. You’ve probably known for much longer than they have. Also try to remember that the reason a lot of parents flip their weaves on finding out is that they’re CONCERNED out of LOVE. Remember how I said that coming out is accepting a place in a persecuted minority. The fact of the matter is, identifying as LGBT* is going to make your life that little bit harder … and no parent actively wants that for their kids.

Accept that they need their own time to accept your new identity. It may take minutes, days, months or even years. They will come around in time. They stand to lose something hugely valuable if they don’t: YOU. Remember, there are groups out there especially for LGBT* youths. Should things go wrong, there is help out there (see ‘Building a Bridge’ at the back of the book).

‘I promised myself I would tell my parents if I ever had a boyfriend (I felt that being in a relationship and having to hide it was possibly the crappiest thing ever) – and so I did. I came out during the Easter holidays just after having been asked out by this boy. My parents were surprised and shocked – they hadn’t suspected a thing – and it was weird talking about my gay feelings with them to start with, but over the past year we’ve all gotten more comfortable about it.’

R, 17, London.

If you’re ready to come out, congratulations! Now you’ve got your membership card, you’re joining a legacy of people who’ve gone before, a sense of belonging and queer culture – should you want it. The most important thing is that you are now free to be you AND shout about it from the rooftops. Or not – it’s your choice.

Coming out as LGB* is relatively easy compared with coming out as trans. Once you’ve come out, life pretty much carries on as normal. WHAT? THERE ISN’T A PARADE DOWN THE HIGH STREET? No, I’m afraid not.

Becoming trans requires work. Situations vary wildly. Some young trans people have been dressing in clothes often assigned to the opposite gender* since they were little kids. Some people have been doing so in secret or in a performance-based way as a drag queen or king.

*You’ll note that a lot of this crap wouldn’t be necessary if society didn’t have such closed ideas of what a man should dress like and what a woman should dress like.

When a person comes out as trans, it could mean admitting they sometimes like to cross-dress or that they intend to identify as their chosen gender full-time. As with sexuality, it’s the admitting it aloud part that’s terrifying. This time, however, people expect a physical transformation afterwards.

The process is unique to every individual, but for people wishing to transition into a new gender full-time, there is a set plan. For most people, the first port of call is their GP. People under the age of eighteen will be referred to the Child and Adolescent Mental Health Services (CAMHS), while adults will be referred to a specialist gender dysphoria clinic or a psychiatrist. That is not to say that being trans is a mental illness of itself, but when dealing with such a big step it’s important to establish it’s the correct choice.

The NHS now recommends swift action for people desiring to transition. There are guidelines on the NHS website that you can take along to your GP, as most won’t be experts on this. Once you’ve been referred, you may well start on hormone treatment – for MTF patients, this involves taking oestrogen, and for FTM, testosterone. The effects are sudden and, in some cases, irreversible.

It is important to seek medical help instead of self-administering hormones. The results are better. End of.

Hormones will change how you look and sound, but some trans people also opt for surgery. Some surgical procedures are available on the NHS, but some would have to be bought privately (like facial feminisation procedures). To have genital surgery (it’s worth pointing out here that a huge percentage of FTM transsexuals never have a phalloplasty – or winky job), most surgeons require you to have been living in your chosen gender for about two years.

Obviously, genital surgery is painful and the recovery period is lengthy, so some people choose to not have it. Others, however, feel they need a full physical overhaul. It’s very much about choice and understanding what’s right for you.

One thing is for certain: if you or someone you know comes out as trans, the most important element is the new identity. Choosing a name and making sure everyone uses the correct pronouns is as important as how you dress and look.

Irene, 33, is an MTF transsexual from New Jersey, USA.

I opted for hormones, after taking some time to be sure I wanted this, because it had been my understanding that they are a very important medical step that can produce profound changes in body and mind. For some people, they’re more important even than the things that we have to do through surgery, but I wouldn’t go that far for myself.

I’m given to understand that I personally am on the slower end of the scale of how fast changes tend to occur. I’ve been on hormone therapy for eighteen months now. It was quite exciting for the first couple months, and still is every time I notice some new progress. For a while, I would measure my chest with a tape measure to reassure myself that things were happening there. It wasn’t frightening at all; this has always been my fondest desire, and it’s a quite gentle process, really; there’s nothing to be scared by.

As far as what changed, the first thing I noticed was that my nipples became developed – that is, stopped being shrivelled up like male ones are. Then, over about three months, my hips widened, from thirty-two inches to forty inches! I was still presenting as male at work during that period, so that was a little difficult for me, since I couldn’t wear my actual wardrobe and had to find male slacks that sort of fit.

Something should probably be said about facial-hair removal, by the way. Hormones don’t do that (nor do they change the voice, which has to be done through practice and often special training), so I had sessions for that every weekend. There’s a controversy about whether laser treatment or electrolysis is better, which prevents there being good advice in the community on it. The facts are that laser covers many times more follicles per session, while electrolysis is always permanent, even on tough follicles. So what everybody winds up doing is laser to get a clear face at first and electrolysis later on to finish the job.

But nobody gave me this advice! So I just went for electrolysis, concurrently with starting hormones, because I didn’t know any better. It was intensely painful, but I actually viewed that as a good thing, since it gave me some concrete sense of progress that I wasn’t getting from the hormones at that time. Also, since most trans women (though I hardly knew any back then) have been through it at some point, there was a sense of belonging, which was nice.

For the first eight months or so, I had virtually no breast growth – enough that I could tell things had happened, with my shirt off, but it was quite distressing. They finally did start growing – I talked to my doctor and we played with my dosages a little – but I’ve never had the ‘growing pains’ sensation that almost everybody mentions. As of today, I wear a B cup, but I don’t really fill it.

I don’t view that hormone therapy, nor the genital surgery that I am also seeking, as cosmetic at all; it’s correcting a vital mismatch between body and soul. But the insurance company will see it that way on both counts (what could be less cosmetic than a complete change of genitalia?), so I’ll be paying out of pocket.

I’ve spoken with other trans women on the subject, and most agree that there is an improved capacity to feel emotion. I can definitely confirm that in my own experience; it’s too pronounced to be psychosomatic. Frankly, I don’t like the person who I was before starting hormones, and I never want to be that coldhearted again. Also, I am able to summon tears when I feel the need, nowadays, which I never was before. Tears are very liberating.

In addition to increased emotionality, I had an almost immediate mood improvement. I had been depressed my whole life. For probably ten years prior to hormones, I was also deeply suicidal, making two very serious attempts – with subsequent hospitalizations. Once I got some oestrogen in my system, I could no longer notice depressive ’spiral’ thinking patterns in myself. Even my psychiatrist saw a profound difference and ultimately took me off most of the psychiatric medications she had had me on, because, as we both agreed, they were no longer relevant to me. It was a complete turnaround, which is something that ’just depression’ patients never, ever experience. Beyond doubt, oestrogen saved my life.

There are other aspects of transition which you didn’t even tangentially ask about, so I won’t go into them all, but just to name a few: There’s the social side – telling one’s friends (and, generally, losing most of them); telling one’s family; losing any spouse and children that one might have. There’s the clothing side, presenting as oneself regarding attire, hair, make-up and so forth. There’s the legal side, fighting with every single political and corporate entity that you had no idea even existed – I currently can’t open a Verizon Internet-service account in my new apartment because, in my new legal name, I have no credit history. Then there’s the fact that, as a woman who plays video games, I face a hell of a lot of name-calling and hate speech from the twenty-something males who inhabit the same virtual spaces as me. And there’s the fact that software development, my profession, is at least ninety-five per cent male.

I wouldn’t trade any of these problems for the world. I am so, so glad to have them.