CHAPTER SIXTEEN

Confederacies

PAYAMATAHA LAY DYING. At the time of his birth, the Chickasaws could count the French, Choctaws, and Quapaws among their many enemies. Six decades later, in 1785, Payamataha could look back on a remarkable transformation. Once a formidable warrior whose hatred for the French was renowned, Payamataha had led his people to peace. For two decades, he had worked with other Chickasaw leaders to change his people’s place in the world, and he had succeeded. Once called “the most military people of any about the great river,” the Chickasaws were now known as peacemakers.1 Only the Kickapoos remained to be fully folded into the Chickasaw peace. Payamataha could look back on his work with pride and hope that his successors would continue to protect Chickasaw independence through a commitment to peace.

However, in the coming years, Payamataha’s small nation would have to contend with a changing landscape, as neighboring political entities sought to combine to increase their power. The next Chickasaw leaders would find it increasingly difficult to remain independent while confederacies grew around them. The fate of Payamataha’s people would illustrate the paradox of independence. He had worked to protect Chickasaw independence through unilateral peacemaking, but when coalitions insisted that the Chickasaws prove themselves by breaking peace with others, his strategy broke down. As in the past, independence depended on others.

Beginning in the mid-1780s, American immigrants by the thousands poured over the Appalachians, and many prominent Americans sought to speculate on large landholdings to divide and sell to settlers. While Chickasaw leaders continued to employ peaceful methods of diplomacy to protect their independence, other southeastern Indians, including Alexander McGillivray, advocated that Indians should surrender some local and national independence in favor of a Southern Confederacy that would join the Northern Confederacy being led by Mohawk Joseph Brant. Together they should form a “Grand Indian Confederacy of the Northern and Southern Nations” to fend off what we today would call illegal immigration, although the immigrants saw it as taking land that should belong to them. Alliance with the Spanish and British would keep Indians supplied with European weapons and trans-Atlantic legitimacy. Yet for the Chickasaws, McGillivray’s plan for a Southern Confederacy threatened Chickasaw independent foreign policy-making and could potentially draw the Chickasaws back into war.2

As Indians debated which interdependencies would be useful and which were too dangerous, the westward migrants themselves raised new questions about sovereignty in the Gulf South. They opposed Indian control of the land and Spanish control of the Mississippi, yet they were equally disgusted with their new nation’s failures to live up to the lofty ideals of the Revolution. Immigrants and speculators wanted independence from regulation and taxation but also access to economic connections and the economic security provided by American surveyors, diplomats, and soldiers. They wanted all of the benefits of a strong government with no intrusions on their independence. Congress struggled to honor their expectations while building a nation under the excruciating constraints of the optimistically named “Articles of Confederation and Perpetual Union.” Some Americans wondered if Spain, Britain, or even Indians might better protect their independence and prosperity than this weak new government. Like Alexander McGillivray, George Washington and other national leaders found it difficult to persuade people to give up some independence to secure their country’s permanent independence.3

The failings of the Articles of Confederation are well known, yet it is important to remember that they were in operation for over a decade during what John Quincy Adams, in his commencement address at Harvard in 1787, termed “this critical period.” According to young Adams, “the prospect of public affairs is dark and gloomy,” and “the bonds of union which connected us with our sister States, have been shamefully relaxed.”4 Both among and within the States, Americans found that their interests often seemed incompatible. In the 1780s, they would need to decide what sort of a confederation they wanted to be, if any at all. It might turn out not to be a “Perpetual Union.” Meanwhile, Spanish officials began to hope that the very immigrants who were causing the problems might cease being Americans and become independent Spanish allies or even dependent Spanish subjects. As multiple sovereignties tried to band together to defend against the others, land increasingly became the primary point of contention. The most powerful confederations and alliances would be those that could protect and advance their people’s right to land and international markets for their products. The most successful path to sustained political and economic independence paradoxically involved ceding more power and authority to confederacies, as both McGillivray’s Southern Confederacy and the federalist plan that would come out of the Constitutional Convention ultimately illustrated.

The Southern Confederacy

As Alexander McGillivray worked to centralize Creek foreign policy, he realized that it would be even more effective if implemented in conjunction with other southeastern nations and even Indians to the north. However, trying to make diverse polities contribute to united military action would be at least as difficult for southern Indians as it was for the British empire or the Continental Congress.

In 1785, knowing that Diego de Gardoqui and John Jay were negotiating borders in New York City and having promised the Northern Confederacy to convene a council to discuss coordinated action, McGillivray invited the Creeks, Chickasaws, and Cherokees to meet in a “general convention” at Little Tallassee in July 1785 to discuss what to do. The delegates crafted a joint resolution for the Spanish king. Because Congress would try to persuade Gardoqui that Creek, Cherokee, and Chickasaw lands belonged to the United States, the nations “in the most solemn manner protest against any title[,] claim[,] or demand the American Congress may set up for or against our lands, settlements, and hunting grounds.” Because “we were not parties” to the Treaty of Paris, the Indians declared, they would “pay no attention to the manner in which the British negotiators ha[ve] drawn out the lines of the land in question.” Indians had not been in Paris, and the British could not speak for them. The Americans well knew that “from the first settlement of the English colonies of Carolina and Georgia,…no title has ever been or pretended to be made by his Britannic Majesty to our lands except what was obtained by free gift or by purchase.” Despite understanding the illegality of Britain’s cession, Americans had, on the Cumberland and Oconee rivers, “divided our territories into counties and sat themselves down on our land, as if they were their own.” The Indians called on Spain to use its power to challenge these baseless claims. They reminded the king that they did not “forfeit our independence and natural rights” to anyone.5

At the council, McGillivray proposed going much further than a joint resolution. He proposed that to defend their “independence and natural rights” against non-Indians, the Creeks, Cherokees, Chickasaws, and Choctaws surrender some of their national independence to a Southern Confederacy, to which they would also invite the Shawnees who had settled in Creek country. As “Nations in Confederacy against the Americans,” with the Creeks as “the head and principal” in the south, they would fight the Americans together. Spain would fulfill its promises made at the end of the war to provide weapons and to negotiate for its Indian allies in the capitals of Europe and the United States.6 The previous year’s attempt by Northern Confederacy Indians to pull southeastern Indians into a “General Confederacy” had failed when the Kickapoos and Chickasaws could not get along, but a separate and allied Southern Confederacy might work.7 Southern Indians had been at peace with one another since Payamataha’s mediation of the 1760s, and the new Southern Confederacy could coordinate with the Northern one whenever possible. McGillivray figured he could be the glue holding the Southern Confederacy together, as he was already coordinating the Creeks’ diplomacy with Spain. Indeed, by 1788 he would describe himself to Europeans as “head of a Numerous brave Nation, and of a Confederacy of the other Nations.”8

McGillivray saw parallels between his efforts and the founding of the United States. Like George Washington and John Adams, McGillivray hoped to make a loosely affiliated people into a lasting nation. He held what he called “the honest ambition of meriting the appellation of the preserver of my country.” Americans ought to recognize a little of themselves in the Creeks if their dispute in fact turned to war. After all, McGillivray pointed out to Congressional Superintendent of Indian Affairs in the Southern District James White, the thirteen colonies had come to a point in 1775 when, “after every peaceable mode of obtaining a redress of grievances having proved fruitless,” they resorted “to arms to obtain it.”9

There were internal parallels as well. Although McGillivray directed most of his centralizing efforts toward foreign policy, like the American revolutionaries he needed to persuade his fellow citizens to comply. Rather than the Revolution’s tarring and feathering, McGillivray had a group of men from his clan who tried to intimidate people who opposed his policies. At one point in a disagreement with the headman Hoboithle Miko, McGillivray ordered his house and goods destroyed.10

If McGillivray could consolidate the Creek Confederacy into a Creek Nation, welcome additional towns such as the Chickamauga Cherokees and Shawnees who had moved to Creek Country during and after the Revolution, lead a Southern Confederacy in league with the Northern Confederacy, and secure supplies from Spain and Britain, he could create a network of interdependencies that could help them all stay independent of the United States. To continue his plans into future generations, he sent his nephew Davy Taitt, the son of his sister Sehoy and British Indian Agent David Taitt, and his son Aleck to be educated in Scotland. In 1782, when the British evacuated Savannah, Lachlan McGillivray had returned to Dunmaglass, where he grew up. While at Dunmaglass he managed the estates of his extended clan. Scotland had surrendered some political independence to England and in return received the commercial benefits of being in its union and local rule in most matters. This was not a relationship McGillivray would want for his Creek Nation, but it was a dependent role that he hoped others such as the Chickasaws would accept when joining the Southern Confederacy. He might have remembered, though, that Scotland did not join willingly.11

McGillivray was prepared to fight for Creek independence and, like the thirteen colonies, would need regional confederation and European alliance to succeed. By the 1770s, after decades of warfare, the Creeks, Chickasaws, Choctaws, and Cherokees were working as allies with one another and with the Spanish, in part because Payamataha had made them allies. Becoming the kind of Southern Confederacy that McGillivray had in mind would prove much more controversial. In the future, he would chastise and threaten southeastern Indians who violated the Confederacy he believed he had created.

War Against Georgia

Small-scale Creek raids against Georgia began again in the fall of 1785, and after the Congress at Pensacola with the Spanish and the meeting to create the Southern Confederacy, McGillivray was ready to urge the Creeks toward a more comprehensive war. Yet when the Creeks received notice from Congress that it had finally appointed commissioners Benjamin Hawkins, Andrew Pickens, and Joseph Martin, McGillivray agreed to meet with them, hoping that the appointments were a sign that Congress could discipline its states. Still, he chided Congress for taking so long. He wrote Pickens that “when we found that the American independency was confirmed by the peace, we expected that the new government would soon have taken some steps to make up the differences that subsisted between them and the Indians during the war, and to have taken them into protection, and confirm to them their hunting grounds.” This kind of diplomacy would have been the right way to end a war. Instead, Congress had been silent, while Georgia was “entirely possessed with the idea that we were wholly at their mercy.” Having heard nothing from Congress, McGillivray wrote, “we sought the protection of Spain, and treaties of friendship and alliance were mutually entered into: they to guaranty our hunting grounds and territory, and to grant us a free trade in the ports of the Floridas.” Whatever border Spain and Congress eventually settled on, “we know our own limits, and the extent of our hunting grounds” and “as a free nation” would “pay no regard to any limits that may prejudice our claims, that were drawn by an American, and confirmed by a British negotiator.”12

The Creeks decided not to send a delegation large enough to make an agreement. They knew the shenanigans that could take place in treaty negotiations with Americans. The Congressional commissioners’ chosen meeting place was “Galphinton,” a new town west of the Ogeechee River (and therefore on lands the Creeks claimed), named for George Galphin, the trader who had served as Congress’s agent during the Revolution. In their role as negotiators with the United States, Hoboithle Miko and Neha Miko went to Galphinton with about sixty Creeks to “protest in the warmest manner against the encroachments” by American immigrants. They declared that their instructions were not to sign anything or even to discuss a treaty until Georgians evacuated the contested lands. The Creeks who went to Galphinton returned with tales of American incompetence. In the presence of the Indian delegates, the Congressional commissioners quarreled with Georgia’s commissioners, who wanted to force a treaty even though most of the Creek towns were not represented. The Indians watching saw them as “completely ridiculous.”13

After the Congressional representatives and most of the Creeks left in disgust, the Georgians again somehow persuaded Hoboithle Miko and Neha Miko to sign a treaty. McGillivray would later deride them as gullible and even “traitors.”14 But in fact, Hoboithle Miko and Neha Miko were men of moderation performing their assigned roles within traditional Creek diplomacy in the face of this strange new tactic, presenting a treaty as a fait accompli. This treaty confirmed the Oconee cession from the disputed 1783 Treaty of Augusta and added a new cession on the coast south of the Altamaha River, lands that were both Creek and within the claims of Spanish East Florida. In exchange, the Georgians pledged to keep settlement off the rest of Creek land.15

In late March 1786, the Creek National Council met to discuss what had happened and to decide whether to go to war against Georgia. Leaders from all the major Upper and Lower towns met at the Upper Creek town of Tuckabatchee with that town’s Great Chief Mad Dog presiding. Lower Creeks described how when Georgia was a British colony, it was a two-week journey between there and the closest Creek town, but now there were settlements only two days away. Individual Creeks described continually running into Georgians as they hunted on their own lands. Creeks wanted to know from McGillivray if Spain would support them if they went to war. He assured them that the Spanish king “will afford us means of defense…of lands that our fathers have owned and possessed, ever since the first rising of the sun and the flowing of the waters.” McGillivray also argued in the Council that, as the Indians closest to Georgia, the Creeks had a duty to the Southern Confederacy “to check the Americans in time before they got too strong for us.”16

The longer that Georgians encroached on Creek hunting lands, the harder it would be to remove them. The Creeks had tried to live peacefully, but the Georgians strong-armed “every straggling Indian hunter” into signing “an instrument of writing, which they falsely call a grant, made them by the Nation.” McGillivray deemed this practice of getting Hoboithle Miko and Neha Miko to sign treaties “as unjust as it is absurd.” Creeks’ “only alternative” was war. After lively discussion, the Creek National Council unanimously resolved “to take arms in our defense and repel those invaders of our lands.” They agreed to drive off squatters and destroy their settlements but also to try to avoid bloodshed and not to cross into land they recognized as belonging to the United States. They sent word to the Spanish and other members of the Southern and Northern Confederacies to tell them of the resolution and their hope that they would all “consider the Americans as common enemies.”17

War was on. After the council, Creek leaders dispersed to their towns to prepare. In mid-April, McGillivray and Mad Dog of Tuckabatchee sent the leaders red war clubs and bundles of sticks indicating that “the broken days” had begun. The recipient was to make the announcement in his town and then break one stick each day at sunrise. When the last stick was broken, the warriors were to ready themselves for battle while their sisters and wives prepared their weapons and provisions.18 There were plenty of young men eager for war. Not only did they support Creek goals of political independence and territorial defense, they also wanted to fight for the same reasons young men always had—for the reputation of their clan and town and individual glory and prestige. When the time came, war parties rode to the Oconee lands, where they destroyed houses and crops and killed any squatters who put up a defense. Other war parties joined with Cherokees to raid the Cumberland settlements. By the following spring, Shawnees joined in the Cumberland raids, and Northern Confederacy Indians renewed attacks in the Ohio Valley and Great Lakes. War sent squatters fleeing and threw into doubt the claims of speculators.19

As the warriors went to war, McGillivray worked to make good on his promises of Spanish support. In Pensacola he collected musket balls and gunpowder from West Florida Governor Arturo O’Neill. After sending those home on packhorses, McGillivray headed west to New Orleans to meet with Louisiana Governor Esteban Miró. Lower Creek representatives collected ammunition at Spanish St. Augustine. Creeks and Cherokees used the thousands of pounds of powder, musket balls, and flints to inflict serious damage on the squatters.20

Georgians expressed surprise at the attacks. They had misinterpreted the lack of Creek violence as a sign that the treaties were valid and that the settlements were legitimate. According to the Georgia Assembly, the Creek attacks came without provocation. Georgia called on Congress for help, but Congress had no funds to support an expedition and no mandate to send troops at the request of one state. Similarly, states had no obligation to help one another in time of war, so Georgia could only attempt to make military alliances with neighboring states. Georgia also sent Colonel Daniel McMurphy, the state’s superintendent of Indian affairs, to try to negotiate with the Lower Creeks. In early August, the Creek National Council met at Tuckabatchee. Sick with fever, McGillivray fitfully sat through the negotiations. By then, McMurphy had returned home, perhaps fearing Creek violence, but Neha Miko and Hoboithle Miko delivered his offer to withdraw to Georgia’s old boundaries if the Creeks would cede “a small piece of land” on the Oconee.21 Rather than consent to the peace proposal, the Creeks came to “very spirited resolutions” to continue the war until Georgia admitted that the “Treaty of Augusta” and “Treaty of Galphinton” were invalid.22 The Council sent Hoboithle Miko and Neha Miko to try to persuade Georgia to, as McGillivray put it, “remove the cause of our dissatisfaction by recalling from the Oconee lands all the individuals settled there, renouncing all idea of pretension to the disputed lands, and by restraining the settlers within the boundaries established and agreed upon in the year 1773, when Georgia belonged to the British government.”23

Two diplomatic meetings in the spring of 1787 left Creeks unsure whether to continue fighting or to wait and see if their violence thus far was enough to intimidate the United States. First, in April, Congressional Indian Superintendent James White arrived to meet with Creeks and Seminoles in the Lower Towns. Yaholla Miko of Coweta said that elderly Creeks could still remember granting the English permission to build a city on the Savannah River in the 1730s. The English had agreed not to expand beyond Savannah without Creek permission. Yet now “the descendants of a people that have so recently settled on our lands, and have been protected by us,” had forgotten the Creeks’ gift and were trying “to destroy a nation to which they and their Fathers are so much indebted.” It was time for Congress to discipline Georgia.24

The Creeks were disgusted to hear from White that he had no authority to remove settlers. When he suggested making peace without removing the illegal settlers, his proposal was unanimously rejected. However, the Creeks agreed to a ceasefire while White explained their case to Congress.25

In their second diplomatic meeting that spring, Creeks convened in May and June at Little Tallassee to hear a call to war from a large deputation of Hurons, Mohawks, Oneidas, and Shawnees representing the Northern Confederacy. They advocated joining together “for a general defense against all invaders of Indian rights.” Creeks agreed they should work together for the purpose of “restraining the Americans within proper bounds.”26 They gave their assent for the Northern Confederacy to notify the Americans that both confederacies had resolved as a Grand Confederacy of North and South “to attack the Americans in every place wherever they shall pass over their own proper limits, not never to grant them lands, nor suffer surveyors to roam about the country.”27

Despite the insistence in the Articles of Confederation that “no State shall engage in any war without the consent of the United States in Congress assembled,” Congress could not stop Georgia from provoking a war. A few weeks after the council with the Northern Confederacy representatives, several Lower Creeks from the town of Cussita were hunting near some Georgia settlements. They had every expectation of safety. Not only was there a truce, but Cussitas had friendly relations with those settlements. The Cussitas often sold meat to the Georgians before returning home from a hunt. Georgians knew that Cussita Headman Neha Miko had negotiated with them when few other Creeks would and had argued against the war in Creek councils. Despite these ties and the truce, a group of Georgians attacked the Cussita hunters and killed between six and twelve, according to various accounts, and scalped and hacked up the bodies with axes. The survivors attested that the victims had cried out that they were friends from Cussita.28

This attack was a serious escalation of a war in which few thus far had died. Creeks were shocked. A letter representing “the voice of the whole Lower Towns” and signed by Neha Miko demanded of Georgia Governor George Mathews to know why Georgians “have killed your friends.”29 Governor Mathews wrote back to Neha Miko apologizing for the “mistake” and trying to divide the Creeks by proposing a truce with only the Lower Creeks.30 Having traveled to the Lower Towns to deal with the emergency, McGillivray was pleased to witness Neha Miko admonish Georgians for falling “upon our people your real friends.”31 Neha Miko and Hoboithle Miko were the Creeks’ primary diplomats with Georgia, and it was within their role, indeed their mandate, to conduct diplomacy even when other Creeks had decided on war. But when Georgia proved itself unworthy of such efforts, Hoboithle Miko and Neha Miko decided it was time for Creek unanimity. They were not alone. From the north to the south, American violence pushed many a moderate Indian leader into thoughts of war.32

In September, the Creek National Council resolved “to take vengeance.”33 Hoboithle Miko and McGillivray went together to Pensacola to show their unanimity and collect munitions. Cussitas and Cowetas joined the fight. By November, Creeks had pummeled a force of 150 militia under Revolutionary War hero Brigadier General Elijah Clarke, destroyed multiple settlements, and killed thirty-one white Georgians.34

The Southern Confederacy and Chickasaw Independence

To protect the territorial sovereignty of all Indians, supporters of pan-Indian confederation urged Indians to commit resources to common defense. They believed that the best defense would be to protect the whole border around Indian country rather than individual Indian nations. It was a difficult case to make to separate sovereignties. The Creeks had tried to incorporate the Chickasaws into the Creek Confederacy earlier in the century, perhaps on the same terms as the Alabamas. Now McGillivray believed that the Chickasaws had finally agreed to surrender some of their national independence to a Southern Confederacy. A Creek and Cherokee delegation to London in 1791 told crown officials that the Creeks and Cherokees “are now united into one, and are governed by one Council” and that the Chickasaws and Choctaws were now “swayed in all their public measures” by this Council.35 The Chickasaws and Choctaws, however, did not agree.

The Chickasaws wanted good relations with their Indian neighbors, but they did not believe that they had surrendered independent Chickasaw foreign policy-making to McGillivray and the Creeks. The Chickasaws, like the Choctaws, were far from the American states and were only beginning to experience pressure on their land. They already had direct access to the Spanish and did not need McGillivray’s mediation. The Chickasaws even had an additional source of European trade, French traders in the Illinois country, who brought goods from British Canada. They continued Payamataha’s strategy of peace.36

When Congress invited the Chickasaws to negotiations at Hopewell Plantation on the Seneca River in South Carolina, Chickasaw leaders followed their policy of peace and accepted. On the morning of January 9, 1786, Piomingo and Mingo Taski Etoka formally introduced themselves to Congressional Commissioners Andrew Pickens, Benjamin Hawkins, and Joseph Martin as well as North Carolina’s representative, Congressman William Blount. The two Chickasaw headmen presented white strands of beads to signify peace and explained that “our two old leading men are dead,” meaning Payamataha in 1785 and Mingo Houma in 1784. Piomingo had taken Payamataha’s place as leading diplomat, and Mingo Taski Etoka had taken on the role of Mingo Houma as the Chickasaws’ principal civil chief. The new leaders promised that they came “with the same friendly talks” as their predecessors.37

The Chickasaws were surprised when the Congressional commissioners presented a draft treaty, although the Creeks could have warned them. As the Chickasaws listened to the interpreter read the treaty, they heard a shocking lack of understanding of the region and its history. The first article declared that, now that the Revolutionary War had ended, “Chickasaws will free all American prisoners and return all negroes and other property.” Piomingo protested that the Chickasaws had no American prisoners or property because they had not fought against the Americans. The second article declared the Chickasaws “under the protection of the United States of America, and of no other sovereign whosoever.” This was the kind of white lie to which the Chickasaws did not mind agreeing, in the spirit of Payamataha’s desire to please everyone. Then the third article began with “The boundary of the lands hereby allotted to the Chickasaw nation to live on and hunt on.” Piomingo stood and halted the reading. Congress could not “allot” lands to the Chickasaws. Chickasaw land was Chickasaw land. Piomingo agreed to proceed only once the commissioners assured him that they “were not desirous of getting his land” and that Congress merely wanted “five or six miles square” for “a trading post” at Muscle Shoals on the Tennessee River (now the northwestern corner of Alabama).38

An American trading post was exactly what Chickasaws wanted. There had been a British post on Chickasaw land in the 1760s and 1770s, and they missed its convenience. With that assurance, Piomingo “readily acquiesced.” Knowing the American reputation for interpreting agreements loosely, Piomingo used a map to mark out the allowed spot and offered that the traders could use some lands north of the Tennessee River to raise crops and livestock for their own use. Piomingo also agreed to the Americans’ plea that the Chickasaws not aid ongoing Creek and Cherokee attacks on the Cumberland. Piomingo even let the Americans believe that Chickasaws might consider fighting against the Creeks if they persisted—a typical Chickasaw pledge meant for assisting good relations with the United States, not actually an offer of military action.39

Piomingo and Mingo Taski Etoka hoped that the meeting at Hopewell would help protect their lands. Chickasaws had heard tales from Delawares, Shawnees, and Cherokees of hordes of squatters, but they were just now seeing the beginnings of them. During the war, they had allowed loyalist refugees to live in Chickasaw country, but now Americans had joined them, and the hundreds of immigrants were starting to act entitled rather than indebted. Repeatedly, Chickasaws had to tell them that they could not simply build houses or pasture their cattle wherever they liked. At Hopewell, Piomingo complained to the Congressional commissioners that there were too many “white people in our land” ignoring Chickasaw sovereignty. When a new immigrant arrived, those already there would “without our permission, or even asking of it, build a house for him, and settle him among us.” Their disrespect for property rights was such that, when a Chickasaw horse got loose, occasionally “they brand him and claim him.” The Chickasaws had decided to kick out all of the white people living in the nation except for the most useful traders, but they needed pressure from Congress on its own citizens to make their policy function without bloodshed. The Commissioners agreed that Congress would warn against illegal settlement, and they approved the Chickasaw “right to punish” disobedient whites.40

In the past, the decision to give five square miles of Chickasaw land for a trading post or anything else was an exclusively Chickasaw decision. But McGillivray and those who agreed with him had adopted a new concept of pan-Indian confederation, one that Nativists in the Ohio Valley had promoted since the 1760s. McGillivray accused the Chickasaws of ceding land “which belongs to my Nation” and threatened to “chastise that people for their fault.” McGillivray went personally to the Chickasaw Nation to try to bring them in line with Confederacy policy.41

Like the Chickasaws, the Choctaws and some Cherokees signed treaties with the United States at Hopewell, while Creek and Cherokee advocates of a Southern Confederacy believed it was their right to use violence to dissuade treaty-making without the approval of the Confederacy. Bands of Creeks and Cherokees tailed both the Chickasaws and Choctaws on their way to Hopewell and stole horses and supplies from their camps. Cherokees attacked Piomingo’s delegation on their way home, taking the presents the Americans had just given them, while Creeks attacked the returning Choctaws. As soon as McGillivray learned of the Chickasaw cession of Muscle Shoals, a party of Creeks rode there and surprised the Americans who had begun building a post, sending them fleeing without time to collect their goods.42

McGillivray’s claim was an audacious one, that the Chickasaws had joined a confederacy that now had jurisdiction over their land. To McGillivray and other proponents of the Southern Confederacy, Chickasaw land was now Confederacy land, at least vis-à-vis the Americans, and the whole point of the Confederacy was keeping the Americans out. If Piomingo continued “failing to keep faith with the general Confederation of the other Nations,” they had the right to force him “to desist from his friendship” with the Americans. McGillivray informed the Spanish that the Creeks, “together with the other Nations of the Confederation, are resolved to exterminate these friends of the Americans among the Chickasaws.”43 Payamataha would have been shocked at Creek threats to assassinate Piomingo and other Chickasaw leaders for exercising their own nation’s independent foreign policy.

As conflict with the Creeks grew, Chickasaws could no longer sustain Payamataha’s policy of peace with everyone. Some Chickasaws wondered if it was time to jettison Payamataha’s policy and take up arms with the Creeks against the Americans. Right after the convention with the Creeks and Cherokees in 1785, some Chickasaws had circulated a message to the Quapaws and their other allies about joint action if the Americans attacked. These Chickasaws had advised that if Northern and Southern Indians worked together and recruited both British and Spanish support, perhaps “they can destroy them or drive them from all these continents.”44 In 1786, some Chickasaws traveled to Creek country and to Spanish Natchez and Mobile to complain about Chickasaw leadership. The old policy of negotiating with multiple sides would not work if Chickasaw unanimity devolved into real factions and even intra-Chickasaw violence.45

While the Chickasaws maintained a tenuous peace, evidence of the need for anti-American action grew. In 1787, one group of American squatters floated down the Ohio and Mississippi rivers and formed a settlement at Wolf Creek, only a half day’s journey from a Chickasaw town. Even Piomingo had to agree that “the Americans intend to take all our country before they are done.”46 Attempting to persuade the Americans to move farther away, Piomingo and Mingo Taski Etoka offered them a tract on Chickasaw Bluffs, but many Chickasaws objected to these concessions and were “murmuring that now the Americans had obtained one piece of land in the neighborhood of their Nation they might soon expect to hear of further encroachments.”47 Indeed, within three years, emigration agents were advertising in Maryland for settlers to come to Chickasaw Bluffs, where they could have one hundred acres for $13.50 plus traveling expenses. The advertisement claimed that the Chickasaws were “a peaceable, friendly, and humane people” who had made “repeated and pressing solicitations” for the settlement. If that stretch of the truth did not persuade immigrants, the agent added a big lie: Despite the name, the Chickasaws lived far away from Chickasaw Bluffs, “down in Georgia, about 120 miles distant.”48

When faced with an American trading post in the heart of Chickasaw country, the Southern Confederacy employed violence to discipline the Chickasaws. In the spring of 1787, when Congress had not renewed its attempt to build a trading post, Piomingo invited Georgia Commissioner William Davenport to build one. As the Georgians were working on construction, a party of Creeks rode in. Not bothering to speak to the Chickasaws and Choctaws present, the Creeks killed Davenport and six others, dispersing the rest. Shocked at this violence on their own land, the Chickasaws “stood nearby speechless.” The Creek party headed for home, making a point of riding through Chickasaw towns displaying the seven scalps and seventy rifles they had seized. Soon thereafter, McGillivray sent messages from the Southern and Northern Confederacies to the Chickasaws and Choctaws demanding that they “declare themselves openly, whether we are to consider [them] as friends or not.”49 Chickasaws continued to demand that Congress build a trading post, and a joint Chickasaw-Choctaw delegation traveled to New York in 1787 to press the point. President Washington would attempt again in 1790, in hopes that a military force at Muscle Shoals would “enable us either to intimidate the Creeks or strike them with success,” but Creeks, Shawnees, and Cherokees drove off that attempt as well.50

McGillivray urged the Spanish to help him punish the Chickasaws. He suggested to Governor Miró that if war against the Chickasaws and Choctaws broke out, they should not receive any Spanish supplies. But he also recommended that if the Chickasaws and Choctaws fell in line, then the Spanish should send them more goods at better prices to prevent American recruitment. For McGillivray, effective violence and improved trade would ideally show the Chickasaws and Choctaws the power of the Southern Confederacy and confirm his position in charge of the Confederacy’s foreign relations.51

The Spanish Empire and Its Dependencies

Louisiana Governor Esteban Miró agreed that the Chickasaws should not recruit American trade. At the 1784 Mobile congress, the Chickasaws had agreed not to admit any trader without a Spanish passport. Yet not only had they allowed Americans into northeastern Chickasaw territory, they had also given William Davenport a spot for a trading post near the Mississippi River, clearly within Spanish dominion right across the Mississippi from the Spanish colonial town of Ste. Geneviève. Still, Spanish officials’ vision of their alliance with southeastern Indians was not the same as Alexander McGillivray’s. The Spanish believed they were in charge. Indian nations could govern themselves internally but should follow Spanish guidance in foreign relations. In fact, the Spanish view looked a lot like both Britain’s wartime view of Indians and McGillivray’s view of the Southern Confederacy, but with Spanish officials on top. Indians should be dependencies within a strong and expanding Spanish empire.52

Despite these differences of opinion, the Spanish relationship with southeastern Indians could work well as long as they maintained mutually compatible layers of sovereignty. The Upper, Lower, and Seminole towns, paths, and agricultural and hunting lands were Creek but within the claims of the Spanish empire. Although colonial officials pined for true control, they knew that the Creeks controlled their lands. The Creeks in turn did not mind if European mapmakers labeled their region Spanish. When an American emissary tried to persuade West Florida Governor Arturo O’Neill that the United States and Spain were on the same side against the “savage” nature of Indians, O’Neill saw this rhetoric for what it was, an attempt to get Spanish arms out of Creek hands. O’Neill’s representative responded with Spain’s own self-serving but more accurate principle of Indian sovereignty, claiming that the governor “makes it a rule never to direct or influence anything that the Assemblies of the Nations ought to decide.” The Pensacola Congress, he explained, granted Creeks and others “the commerce and the protection of our Monarch…without encroaching on their laws or customs.”53

Disputed lands on the edges of Creek country were more complicated for Spain. Spanish officials sympathized with the Creek argument that Georgians were squatting “on their hunting lands” and that Spain’s treaties with southeastern Indians obligated it to protect them from the encroachments.54 The responsibility was double if the lands also fell within Spain’s colonial borders. Diego de Gardoqui and John Jay still had not rendered a treaty delineating the border between Spanish colonies and the United States. If the Spanish empire extended as far east and north as King Carlos III maintained, then Georgians had settled on Spanish land without permission. However, if the border with the United States was west of Oconee, things got trickier. For their part, Georgians interpreted sovereignty unilaterally. To them, these lands were part of Georgia, and they could not be ruled by Spain, the Creeks, or even their own Congress. At least some Georgians extended their border claim to the Mississippi River and believed that all of Creek country was “within the State of Georgia.” In these Georgians’ view, Indians had no “rights at all but what are subservient to or dependent on the legislative will of the State claiming Jurisdiction over the lands they live and hunt on.”55

Spain’s policy was secretly to fund Creek action, making it impossible for Americans to settle beyond Spain’s ideal borders and thereby persuading Congress to agree to Spain’s treaty terms. Gálvez instructed Miró to give the Creeks powder, ball, and guns but “with the greatest secrecy and dissimulation.” Miró was to pretend that they were regular trade goods for hunting, not war supplies. If the Americans retaliated against the Creeks on land that was either clearly within the Spanish empire or disputed between Spain and the United States, then Miró was authorized to force them all the way back across the Oconee.56 Keeping thousands of pounds of muskets, powder, and ball secret was not actually possible, of course. The keepers of the royal warehouses in St. Augustine, Pensacola, Mobile, and New Orleans could try to hide the transfer, but they had to involve scores of clerks and laborers. More to the point, secrecy was not in the Creeks’ interest. Creeks pointedly boasted to Americans of Spanish support, hoping to intimidate Americans into compliance.57

Hiding Spanish support and debating the exact line between the United States and Spanish West Florida mattered little to Creeks. It was all Creek country, and they had a right to defend it. If Spain was truly their ally, it should help protect all Creek lands against incursions that flew in the face of international diplomacy. Creeks had the sovereign right to defend their own territory and make alliances to assist in that defense.

For Spain, however, the path to imperial control over its colonies did not set a high value on the independence of Indians. In 1786, based on his experience on the Gulf Coast, Gálvez devised the official instructions for Indian relations in the northern part of the empire. Bernardo de Gálvez was soon in a position to implement his vision of expanding the Spanish empire with the help of Indian allies. Like British Indian Superintendent John Stuart in the 1760s and 1770s, Gálvez had come to believe that Indians held a vital place in European imperialism. If Indians agreed to exclusive trade and protected their interior lands from rival European empires and the United States, the relationship would work well. In the short term, faithful Indian allies should receive guns, gunpowder, ammunition, and other manufactured goods. But Gálvez’s long-term goal was Indian dependence. “Accustomed to guns and powder,” Indians would forget how to make and use bows and arrows and eventually be “unable to do without us.” Then the Spanish could truly rule. Dependent on European goods, Indians might “possibly improve their customs by following our good example, voluntarily embracing our religion and vassalage.” If not, Spain could disarm them and control them by force.58

Governor Miró tried to apply Gálvez’s strategy of transforming the Creeks into dependent vassals. Aiming to rein in Creek independence and control their relations with the United States, Miró in March 1787 ordered that Creek supplies be cut off to encourage them to make a truce with the Americans. Miró figured that the Creek victories thus far would make Georgians agree to Creek terms. Stopping the war now would leave Georgians cowering on their side of the Creek border but prevent the war from drawing in the Spanish or other states. Miró ordered Governor O’Neill at Pensacola not to give the Creeks any more munitions unless the Georgians attacked them at home, a decision supported by Miró’s superiors. The king agreed that the Creeks should be on the defensive and hold on to their munitions “in case they are invaded.”59 To the Spanish, this seemed a reasonable policy toward all concerned and the most likely to strengthen Spanish authority over its allies and to curb the United States without making it into an enemy. In the coming years, the decision to withhold arms would have disastrous consequences for both the Creeks and the Spanish.

The Independent Nations of Kentucky, Cumberland, and Franklin?

Alongside the United States, Spanish and British colonies, and Indian nations, a new kind of polity arose in the decades right after the Revolution: settlements of Americans who imagined futures outside the United States. In the twenty-first century, after the United States has prospered for more than two centuries, it is hard to imagine early Americans who did not feel they needed to remain part of the United States. Yet supporting American independence from Britain and the creation of a kingless republic did not mean that all Americans believed that they should forever be part of the United States. There could be more American republics on this vast continent if the U.S. federal government did not suit all of their needs, and people might reject republicanism completely if it could not keep them secure. Indeed, Kentucky and other settlements west of the Appalachians operated largely as independent republics in the 1780s and most of the 1790s. Yet the need for trade and security meant that these small settlements could not stand completely alone. They would need allies. Spain offered these farmers, speculators, and merchants exactly the kind of future that Oliver Pollock had imagined during the war but now found himself too indebted to enjoy.60

Throughout the 1780s, Americans were moving west from the thirteen original states in droves. Before the Revolution, immigrants had come through the Cumberland Gap from Virginia or down the Ohio River from Pennsylvania, in violation of Britain’s Proclamation of 1763 forbidding trans-Appalachian settlement. They founded the “Watauga” or “Holston” settlements at the headwaters of the Tennessee River and “Kentucky” in and around Danville and Lexington (named in 1775 for the victory over the British in Massachusetts). Shawnee and Cherokee attacks during the Revolutionary War cleared out these settlements, but immediately after the war, large numbers of immigrants moved back, assuming that the peace included Indians. Others even moved west of Holston to the Cumberland River Valley around Nashville. By the end of 1785 some twenty-five thousand settlers lived in the Kentucky region, growing corn, wheat, tobacco, hemp, and cotton, which they traded overland through Fort Pitt (Pittsburgh), much of the corn as distilled whiskey. Holston and Cumberland were smaller settlements, mostly hunting for the fur trade, but they were growing. Farther south than Kentucky, these communities could not develop commercial agriculture without access to the Mississippi.61

Settlers came for economic opportunities, which depended on access to land and markets, and they were likely to award their loyalty to whatever political entity could help them raise and sell cash crops. George Washington observed that “the Western States…stand as it were upon a pivot. The touch of a feather would turn them any way.” He wanted Congress to invest in canals and roads that would give westerners access to East Coast port cities and keep them away from Spain’s or Britain’s promises. Oriented toward the U.S. economy, they would be not only loyal but also industrious and republican citizens, and their participation in turn would secure eastern merchants’ commitment to an expanding interior.62

Congress had no funds to build an infrastructure linking east and west, so western settlements continued to protest that Congress and the states were endangering their lives and livelihoods. For example, Holston was part of North Carolina, but settlers there felt that the state was not protecting the interests of its citizens west of the Appalachians. They believed that their state had an obligation to defend them against Chickasaws, Cherokees, and Creeks who opposed the settlements. Small-scale settlers wanted their state to reduce the power of speculators, while speculators lobbied for state recognition of large land possessions, which they could then sell for a profit. Both expected either the North Carolina legislature or Congress to win them access to the Mississippi and the port of New Orleans, by diplomacy or force.

When their frustration with North Carolina reached the breaking point, the residents of Holston in 1784 declared their independence from North Carolina and constituted themselves as the State of Franklin, named in honor of Benjamin Franklin. At first, the State of Franklin asked Congress for admission back into the United States as the fourteenth state, but North Carolina wanted it back. In Congress, only seven states voted in favor of approving its statehood, when the Articles of Confederation required nine to admit a new state. Writing from Paris, Jefferson himself spoke for many Americans who feared that if Congress admitted this breakaway settlement, the “states will crumble to atoms by the spirit of establishing every little canton into a separate state.”63

People in Franklin and the other western settlements found themselves dissatisfied with their status in the United States. They had many of the problems of the formerly British colonies, including insufficient representation in faraway legislative bodies and the sense that they received little benefit from those who claimed them. Indeed, in Franklin’s deliberations over whether to secede from North Carolina, one delegate pulled a copy of the Declaration of Independence from his pocket and paralleled the grievances listed by Thomas Jefferson in 1776 with theirs in 1784. If the American republic could not give them access to markets and protection from Indians who opposed their land claims, perhaps an empire could.64

Believing that independent trans-Appalachian states would be too vulnerable and isolated from markets, some people imagined creating countries allied with Spain or even colonies within the Spanish empire. Men with plans for the trans-Appalachian West streamed into Diego de Gardoqui’s New York City house at the southern end of Broadway, close to soldiers drilling at the Battery and Bowling Green, where there had once been a statue of King George III. Some of the visitors were Europeans, such as Pedro Wouver d’Arges and Prussian Revolutionary War hero Baron Friedrich von Steuben. Others were U.S. officials and officeholders going behind the back of their government.65

Representatives from the western part of North Carolina even considered independence. During the Congressional debates in the summer of 1786 over whether to change John Jay’s instructions and accept a Spanish treaty that did not include access to the Mississippi, North Carolina Congressman James White (who would soon meet the Creeks as superintendent of Indian affairs in the Southern District) introduced himself to Gardoqui as a large landowner in the Cumberland settlements and an Irish Catholic. White informed Gardoqui that if easterners in Congress managed to push through the bill to change Jay’s instructions, the people of Cumberland “will consider themselves abandoned by the Confederation and will act independently.” If Spain would offer Cumberland access to the Mississippi and the port of New Orleans, “His Catholic Majesty will acquire their eternal goodwill and they, as an Independent State, will draw closer to His Majesty.” Allied with Spain, the independent state of Cumberland would “serve as a barrier” to U.S. expansion.66 In later decades, this kind of negotiation between a U.S. Congressman and a foreign diplomat would obviously be treason, but in the 1780s, White could argue that the fate of the west was still unsettled. Just in case, though, he kept his negotiations secret.

Gardoqui was delighted to receive leaders from other western settlements who also proposed secret plans that involved independent states under Spain’s protection. John Sevier was a militia commander who had fought Dragging Canoe’s Chickamauga Cherokees during and after the Revolution and now had been elected governor of Franklin. He wrote to Gardoqui to request Spanish negotiation between Franklin and the Cherokees and the rest of the Southern Confederacy. In Franklin after his meeting with Gardoqui, James White (still a member of Congress) reported that Franklin’s “leading men” were willing to swear an oath of allegiance to the Spanish king and “abjure the authority of and dependence on, any other power” as long as they could have their own independent “civil police, and internal government.”67 Virginia Congressman John Brown, who lived in Virginia’s Kentucky counties, added to the chorus, assuring Gardoqui that “there was not the slightest doubt that the Kentucky assembly would resolve to set up an independent state, unless war with the Indians threatened them to such an extent that” they had to run back to Congress for help.68 If Spain could help the western settlements obtain uncontested possession of the land and a market for their products and protect them from Indians, they might, as James White put it, “preserve their independence from the American Republics.”69

While Diego de Gardoqui was hearing these plans in New York, other Spanish officials received similar offers. In London, displaced loyalists approached the Spanish ambassador to offer to establish towns on the northeastern edge of Spain’s colonies “in order to form a strong barrier to check any aggression on the part of the United States of America.”70 Kentuckian James Wilkinson traveled to New Orleans to propose an alliance between Spain and an independent Kentucky. In July 1787, Wilkinson introduced himself to Louisiana Governor Esteban Miró as a U.S. brigadier general during the Revolution, not mentioning that he had been forced to resign his commission after being accused of corruption and plotting to remove George Washington as the Continental Army’s commander-in-chief. Wilkinson declared that Kentucky’s leading men had sent him to New Orleans “to open a negotiation” with Spain “to admit us under its protection as vassals.” Wilkinson compared Kentucky’s situation in 1787 to that of the thirteen rebellious colonies in 1776. Debts from the Revolutionary War had made Virginia into the same “oppressive” taxer that Britain had been. What good were governments that sacrificed western interests for eastern ones and levied high taxes without providing western settlers equal representation or “defense against the savages”? If westerners had access to New Orleans, their “forcible dependency” on manufactured goods “will cease, and with it all motives for the conjunction with the other side of Appalachian Mountains.” Wilkinson predicted that Franklin and Cumberland would follow Kentucky and create “a distinct confederation of the inhabitants of the West” and “a friendly understanding with Spain.”71

The following year, Miró heard similar proposals from a more familiar man: Oliver Pollock. Now out of jail, Pollock had begun to imagine that the postwar world he had worked for, one that tied the agricultural produce of Kentucky and the Ohio Valley to Spanish markets around the world, might happen without the United States. In Philadelphia, he met James Brown, a member of Virginia’s Congressional delegation from the Kentucky counties. Brown told Pollock, as he also told James Madison and Thomas Jefferson, that Kentuckians were so upset with Congress’s reluctance to let them separate from Virginia that they would soon declare themselves an independent republic with a commercial relationship with Spain. This move would open a lively Mississippi River trade in flour, tobacco, and slaves, and Pollock would be the ideal merchant to manage it. Brown had promised to send Pollock the independence resolution as soon as it passed so that Pollock could give it to Miró to pass up to the crown. Perhaps the Pollocks’ future could lie with Spain and discontented Americans.72

As Pollock prepared to travel to New Orleans, he heard that a devastating fire in March 1788 had leveled New Orleans northwest of the Place d’Armes and destroyed the Cabildo from which Bernardo de Gálvez had inspired New Orleanians after the hurricane of 1779. As Pollock loaded his ship for the journey, he included building materials and a pump fire engine bought from Benjamin Franklin to give to Miró, in hopes of getting back on the governor’s good side. In New Orleans, Pollock told Governor Miró of the Kentuckians’ situation and proposed to import flour and tobacco from Kentucky, as well as Philadelphia if possible, free from duties, into New Orleans and to Spanish ports beyond. The income could go toward paying his debt to New Orleans merchants and the Spanish government. Miró granted Pollock’s request but had to inform him that he had already extended the same privilege to James Wilkinson.73

Miró, Gardoqui, and other Spanish officials were too dazzled by the temptation of creating anti-American dependencies to remember that such rebellious citizens were unlikely to be dependable subjects or allies. Following Bernardo de Gálvez’s wartime model of offering British West Floridians security, land, and markets, they eagerly welcomed American dissidents. While encouraging U.S. citizens to rebel against their government was not internationally acceptable, Miró wrote, “should it happen that they could obtain their absolute independence from the United States,” then Spain might treat them like any other nation regardless of Congress’s opinion.74 And at least some of Franklin and Cumberland fell within Spain’s land claims anyway. The time seemed right to take advantage of, as Governor Miró put it, “the state bordering on anarchy in which the Federative Government of the United States finds itself.”75

Similarly, Gardoqui explained to the crown that there was danger ahead for the Spanish empire “if this rapidly-growing young Empire,” the United States, “unites as it grows”; however, if Spain acted now, it could win them, not by force but “by tact and generosity, leaving them their customs, religion and laws, on the supposition that in time they will be imperceptibly drawn to ours,” especially because their own government was so incompetent.76 If Spain did not act, Britain surely would gobble up these places, adding them to Canada and perhaps eventually taking Louisiana, exactly what James Bruce and Lord Dunmore had proposed. Then the Gulf Coast victories would be lost, and Britain would “bless the day her colonies rebelled and thus brought her this opportunity.”77 Gardoqui hoped Congress might even let the west go willingly, realizing that spreading west would hurt the United States by draining its population and bringing down eastern property values with too much cheap land. King Carlos III wholeheartedly agreed. In 1788, he legalized the sale of Mississippi and Ohio Valley goods out of New Orleans, and he offered free trade to men working to separate from the United States.78

From Spain’s perspective, it all could work out perfectly for Spain as well as for Indians and trans-Appalachian immigrants, all of whom should recognize that they needed a strong and benevolent sovereign to keep the peace and promote prosperity. Even some people on the ground envisioned cooperation. In the spring of 1788, emissaries from Cumberland traveled to Creek country to tell Alexander McGillivray “that Cumberland and Kentucky were determined to free themselves from a dependence on Congress, as that body could not or would not protect their persons and property nor encourage their commerce.” The men from Cumberland said that they were willing to be allies of the Creeks and subjects to the Spanish king.79

In return for becoming dependents of Spain, western immigrants wanted Spain to prevent Indian attacks, thereby providing safety for their families and a secure possession of the land. James Robertson of Nashville informed Governor Miró that Cumberland was “daily plundered and its inhabitants murdered by the Creeks, and Cherokees, unprovoked.” Surely the rumors were untrue that Spain was “encouraging the Indians to make war on us and furnishing them with ammunition.” If Spain could provide the protection that Congress could not, the Cumberland settlers would “remain a grateful people.”80 Of course Miró had supplied Creek and Cherokee attacks in the past and knew both that the violence was not “unprovoked” and that he had little power to stop Indians from retaliating when Americans invaded their lands. Still, Miró urged McGillivray to make peace with settlements that were willing to ally with Spain.81

The problems in Spain’s promise of protection and prosperity to both Indians and former Americans were evident in the State of Franklin’s demand to “increase their territory by being allowed to extend along the Cherokee and Tennessee Rivers” to the headwaters of the Yazoo and Mobile rivers. These lands might or might not be within the Spanish empire, but they were indisputably within the purview of the Creeks and the Southern Confederacy. Spanish officials recognized that the land requests violated, as one official put it, “the equity with which the Indians should be treated, leaving them lands for hunting and cultivation.”82 But westward immigrants did not much care about that kind of equity, and neither did Indian nations, who completely rejected the idea of being left only some of their lands.

Ultimately the Spanish hoped to use their access to resources and the world beyond North America to create dependencies of Indians and former Americans, all under a rising empire. John Jay worried that they would succeed and split Americans “into three or four independent and probably discordant republics or confederacies, one inclining to Britain, another to France, and a third to Spain, and perhaps played off against each other by the three.” Then, Jay concluded, “what a poor, pitiful figure will America make.” Spaniards and Indians thought this future seemed just about right.83

Americans into Spaniards

Another group of Americans offered to become Spanish subjects directly, by immigrating to the Spanish Floridas and Louisiana. Moving one’s family out of the U.S. republic and into a Catholic foreign colony seems like a step backward from Revolution and away from independence, but these families did not see it that way. Like other Americans, they sought land and access to markets, the building blocks of personal and familial independence. Seeking them in a stable colony seemed more promising than creating a new independent nation surrounded by more powerful colonies and Indian nations.

To Spain, inviting American immigration was less politically controversial than undermining the United States by arming Indians or encouraging regions to separate. Although Bernardo de Gálvez had warned Miró to “remain very cautious” about American immigrants and had even barred settlement by Protestants after the Treaty of Paris, by 1787 Miró believed that disappointment with Congress might turn immigrants into good Spanish subjects.84 Surely “men who have lived under a precarious government, that did not give them any protection, surrounded by the peril of Indians, destitute of trade,” would be loyal to a government that in contrast “protects them, facilitates an outlet for their products, decides their controversies with justice without exacting any tribute or molesting them in their domestic operations.” Spain could win the affection of the immigrant generation, and future generations “will know no other fatherland than this one.”85

Miró offered immigrants a deal designed to make them grateful subjects. Any “good inhabitant” was welcome to a land grant big enough for a family farm, from about two hundred acres for a small household to nearly seven hundred for a large one. Every head of a family must “take the due oath of allegiance to his most Catholic Majesty,” agreeing “to take up arms in defense of this province against whatsoever enemy who could attempt to invade it.” Once they swore allegiance, they would “enjoy the same franchises and privileges” as other subjects and “be governed by the same laws and customs.” They would have a free market at New Orleans for their produce, exempt from all duties and taxes. They would not be required to convert to Catholicism or financially support the church, although “no public worship shall be allowed but that of the Roman Catholic Church.” Some could have the plantations that James and Isabella Bruce and other fleeing loyalists had left behind on the Amite and surrounding rivers just west of the Mississippi.86

Thousands of Americans accepted Spain’s offer. Some were speculators seeking to organize new settlements and sell off the land in smaller parcels or at least extract payments for transportation. Most were landless Americans hoping to find the family independence promised by the Revolution by owning their own small farms, even if those farms ended up within the Spanish empire. The typical immigrants looked like the Richards family of Kentucky: a husband, wife, and one child, who floated down the Ohio and Mississippi rivers to Natchez, bringing with them their only property: an ax. The immigrants floated downriver by the hundreds on ramshackle rafts. Miró noted that the boats had no keels or oars. They could only float downriver—it was “impossible to make them return.”87 Twentieth-century America saw many episodes of refugees piling into flimsy boats, trying to reach the promise of the United States. In the late eighteenth century, it was Americans who put all they owned on quickly constructed vessels to float toward Spanish opportunity.

Colonel George Morgan, who as Congress’s Indian affairs agent during the Revolutionary War had proposed invading West Florida and making it the fourteenth state, chose Spanish over American opportunity. In 1788, he collected investors, including Oliver Pollock and Aaron Burr, into a New Jersey Land Society and received permission from Congress to buy a large tract of land in the Illinois country. Congress granted permission but at a higher price than Morgan had requested, two dollars for every three acres rather than one dollar. While Morgan was considering the terms, he was also discussing with Gardoqui a similar idea, but in Spanish Louisiana. In January 1789, Morgan left Pittsburgh with four boats carrying about sixty adults and children, many of whom were German immigrants, for a place on the Mississippi River that he called “New Madrid.” Using his investors’ funds, Morgan planned to sell the lands to the settlers and make a tidy profit since Spain was giving the land away.88

Part of Morgan’s advertising to potential settlers was that “there is not a single nation or tribe of Indians, who claim, or pretend to claim a foot of the land.” Indeed, while most of Spain’s empire north of Mexico was owned and occupied by Indians, New Madrid, west of the Mississippi River, actually was Spain’s to give away. Nearby Osages and Quapaws did not use that land and believed that a post would bring useful trade to the region. Morgan chose a site on the west bank of the Mississippi about forty-five miles downriver from where the Ohio met the Mississippi, where the settlers believed they could grow corn, tobacco, hemp, flax, cotton, and indigo. They began laying out a planned town with wide tree-lined streets, cabins surrounded by women’s vegetable gardens, and farms for the men outside of town.89

Despite New Madrid’s pro-Spanish name, its founder undermined Spanish authority. When Miró received Morgan’s report, he charged him with trying to establish “a Republic within [Spain’s] own domains.” Morgan was not supposed to sell land that “His Majesty concedes gratis.” Also, Morgan had distributed land in parcels from 320 to a shocking 4,800 acres, much larger than the king’s allowance of two hundred to seven hundred acres. And Morgan had apparently neglected to inform the settlers that they needed to swear an oath of loyalty to Spain and refrain from public Protestant worship. Even the sycophantic name was offensive. Naming cities “is a right belonging only to the Sovereign.”90 Morgan promised to follow the rules in the future, but Miró glimpsed the independence these new supposed Spanish subjects might assume.91

While Spaniards weighed the benefits against the dangers, Indians saw no value at all in welcoming American immigration. These were the very people the Creeks wanted to push back to the Atlantic coast. McGillivray swore that “filling up your country with those accursed republicans is like placing a common thief as a guard on your door and giving him the key in his pocket.” As trader William Panton tried to explain to Miró, the Creeks did not believe these recent Americans had really become Spanish subjects, “for it is a phenomenon quite beyond their comprehension to conceive it possible that a set of men who so wantonly throw away their natural sovereign can be serious in placing themselves under the Government of another.”92

Much more troubling to the Creeks and Choctaws than the trans-Mississippi settlements was the one the Spanish allowed in the hunting lands right between Choctaw and Creek territories on the Tombigbee River north of Mobile. Many of these immigrants were refugees from Creek attacks on the Cumberland who had presented themselves in Spanish New Orleans and Mobile to ask for protection. Choctaws attacked the Tombigbee settlements and recruited Alabamas and Creeks to help. McGillivray told the Spanish that he was urging Alabamas and Creeks not to join the attack, but he may in fact have supported it. He and his sister Sophia had a plantation not far from these new settlements to raise livestock to sell at Pensacola and had actually invited British traders and loyalist officers they had known during the war to settle there. But the new immigrants were far more numerous and soon began to spread beyond the lower Tombigbee, deeper into Creek and Choctaw country. During the winter of 1788-1789, Creek hunters came across surveyors marking lines ten miles from Little Tallassee itself. McGillivray explained that the uncontrolled spreading “is a thing that I always feared would happen ever since I first knew the intention of the government to introduce Americans.” The Spanish now were seeing firsthand what Indians in the east already knew: “the disposition to usurp that the Americans have if once they are allowed to establish themselves.”93

The Creeks Seek New Allies

The acceleration of Spanish-sponsored immigration at the same time that Governor Miró cut off supplies for the Creek war against Georgia shook the Spanish-Creek alliance to its core. The Spanish had hoped that both the Creeks and the Americans would be impressed by Spain’s ability to bring peace and prosperity to its Indian and non-Indian dependents, but Indians felt betrayed and alarmed. While Miró claimed that the immigrants had become “true Spaniards,” McGillivray believed they were still “Americans in their hearts.”94 He reminded Miró that the security of Spanish West Florida and Louisiana depended on “the security of our establishment as an Independent Nation.”95 Creek independence should not worry Spain. The strong allies could stand together against the disjointed American states. With Creeks united in the decision for war and “victorious over the Americans in every quarter,” the best course now would be “following up the blows lately given to those turbulent people with vigour.”96

Miró’s decision then to cut off supplies was disastrous for McGillivray’s position at home. His role was to nurture the connections that would provide economic and military security. Creeks demanded to know from him whether Spain was still committed to containing the Americans and providing arms and ammunition. McGillivray asked Miró for a copy of the Royal Order that King Carlos III had issued after the 1784 congress to prove to the Creeks that the Spanish had pledged to supply their war. But the Spanish continued to disappoint. Miró sent McGillivray a copy of the Royal Order but, fearing that it would fall into American hands, deleted the part that explicitly mentioned supplying “Alexander McGillivray all of the guns that he has requested for the Creek Indians to attack the Americans.”97

Not only had McGillivray promised Spanish supplies to the Creeks, he was also supplying the Cherokees as part of trying to build the Southern Confederacy. Geographically on the other side of the Spanish from Creek country, the Cherokees expected McGillivray to funnel munitions to them. As he tried to persuade the Spanish to change their minds, McGillivray also pursued three means of reducing Creek dependence on Spanish supplies. He made overtures to selected Americans, frightened the Spanish with the specter of an alliance between the Southern Confederacy and the United States, and considered a proposal to renew the Creek-British alliance.

First, McGillivray built American connections. He wrote the Congressional commissioners that the Creeks were ready to “begin again on new ground.” They would make peace if Georgia would “retire from the Oconee lands to within the limits prescribed to that State when it was a British province.”98 Although the Creeks and Georgia did not reach an agreement, McGillivray’s overtures did lead to a new truce. McGillivray also welcomed peace offers from Cumberland and Franklin. James Robertson told McGillivray that Cumberland was devastated by Creek attacks and had sent him to seek good relations with the Creeks and the Spanish. McGillivray heard from Franklin Governor John Sevier that his state, “now in rebellion to Congress,” desired friendship with the Creeks.99

McGillivray did not trust these “crafty, cunning, republicans.” Rather, he used his negotiations with Congress, Georgia, Cumberland, and Franklin to remind the Spanish that they did not want the Creeks and the United States to get too friendly. He wrote West Florida Governor Arturo O’Neill that the Georgians and Congress seemed ready not only to “secure us in all our claims to our lands” but also to give the Creeks free access to American ports.100 If the Americans bought the products of the Creek hunt for good rates and sold goods from London for prices that undercut Spain, the Creeks would revoke their pledge to trade exclusively with Spanish-approved traders, and Gálvez and Miró’s goal of Indian dependence would be lost. Miró warned McGillivray to “refrain from making any commercial treaty.”101

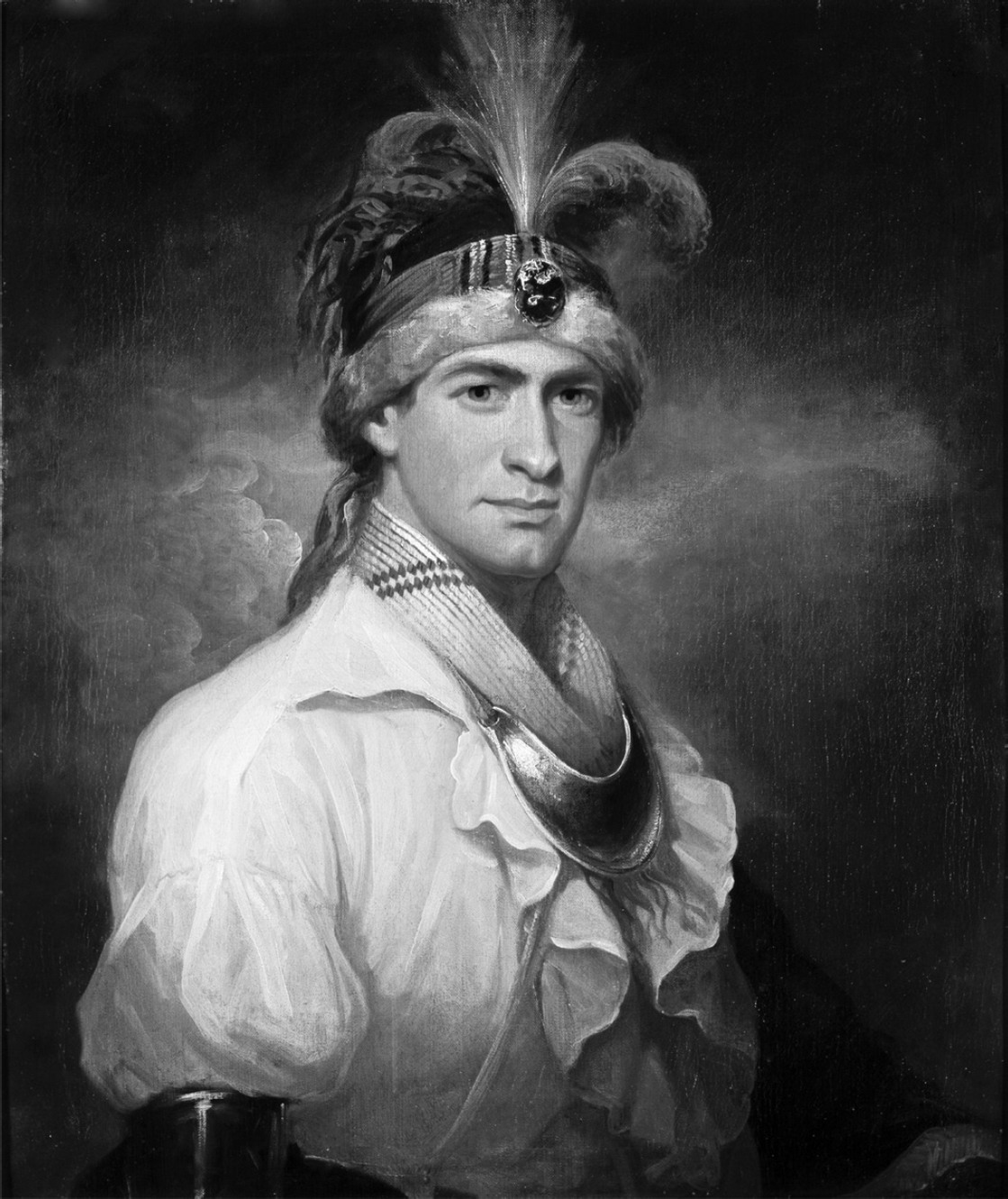

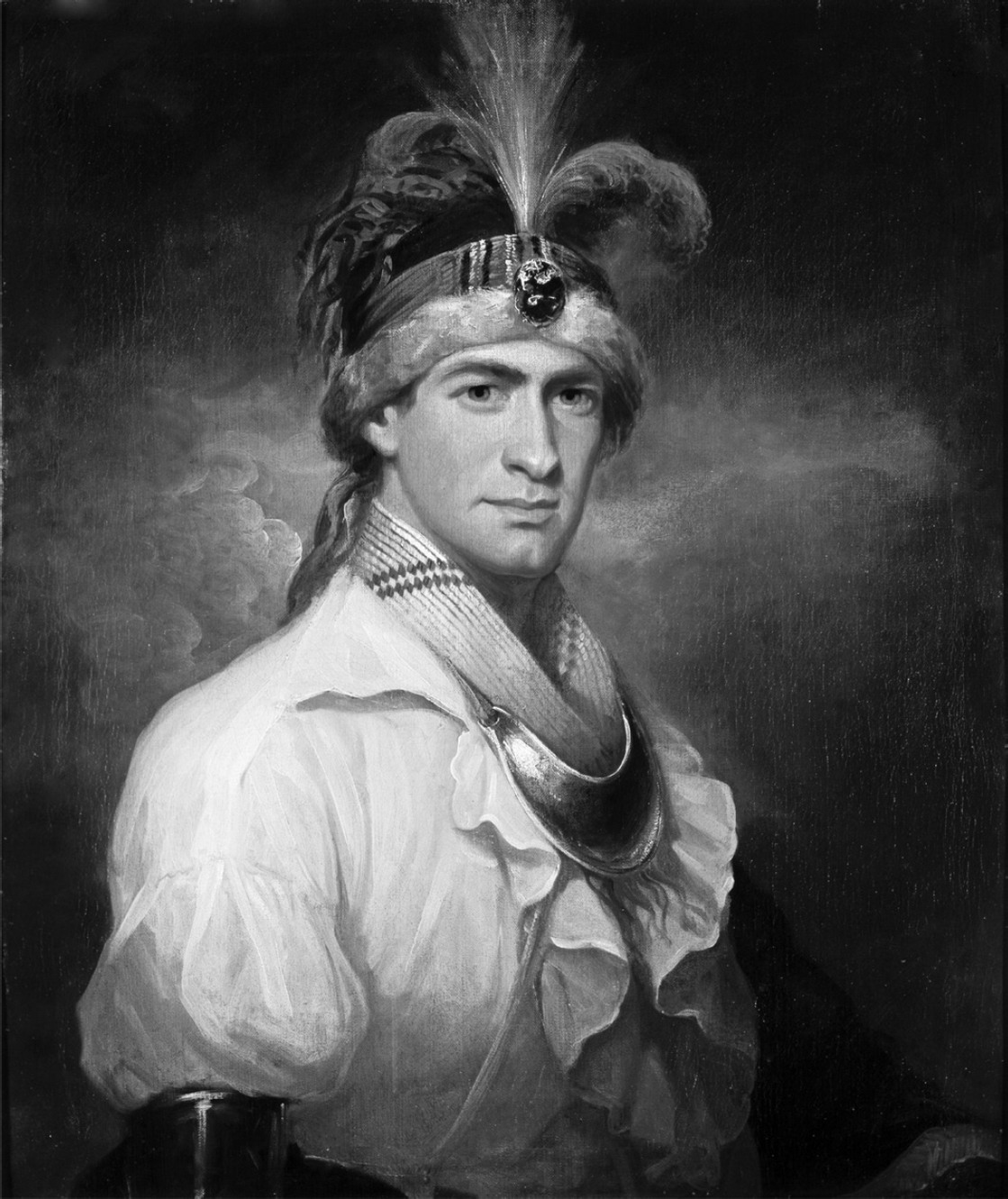

With Spain surprisingly unhelpful and the United States predictably so, a rumor that the British wanted to get involved again in the southeast was welcome news. The bearer was William Augustus Bowles, a young man from a Maryland loyalist family who had joined the Maryland Loyalists Battalion in 1777, at the age of fourteen. Sent to West Florida with the Maryland Loyalists the following year, Bowles had been dishonorably dismissed from British service for insubordination. After that, he lived for a year with a Lower Creek family, the Perrymans, near where the Chattahoochee and Flint rivers come together to form the Apalachicola River. Among the Creeks, Bowles found what he later described as “a situation so flattering to the independence natural in the heart of man.”102 Like many outsiders who visited Indian communities, he imagined that Indians were free to do as they liked, failing to see the obligations of community and labor that bound members of an Indian town just as surely as any other kind of polity. Compared with the British army, his status as a guest in Creek country certainly granted him new independence of movement. Bowles later claimed that the Lower Creeks had adopted him, which is possible. Many Indians of the eastern woodlands practiced adoption, allowing outsiders to join a clan and become one of their people if they gave up their old identity and fully embraced the new.103

After the war, Bowles would try to open trade between southeastern Indians and the British in the Bahamas. In 1781, Bowles had been reinstated in the British army, so he was among the troops evacuated from Pensacola after the Spanish victory, perhaps in the same ship as James and Isabella Bruce. Disinclined to return to Maryland as a traitor or to accept the British offer of land in snowy Acadia (which the British had taken from Amand Broussard’s family), Bowles spent some time in the Bahamas and then returned to the Perrymans in the mid-1780s. There, Bowles heard his Lower Creek friends’ new frustrations with Spanish trade—high prices for European goods, low payments for their furs, and Miró’s recent decision to cut off military aid. As he listened, Bowles made a plan.104

By 1788, Bowles had returned once again to the Bahamas, where he exaggerated his influence in Creek country to John Miller, a member of His Majesty’s Council for the Bahamas who operated a trading house. Bowles explained that Spain had licensed William Panton and John Leslie to provide the trade but that, with “his own influence,” an ambitious trading house like Miller’s would find that “nothing could be easier than to supplant them.”105 Miller had reason to believe him. In the 1770s, he was a trader in West Florida and a member of His Majesty’s Council for West Florida, along with James Bruce. When the Spanish took over in 1781, Miller had fled to the Bahamas but was captured when the Spanish invaded there and until the war’s end was imprisoned in Havana, where he had months to plot his return to West Florida. Miller introduced Bowles to Lord Dunmore, who became governor of the Bahamas after Britain lost Virginia and South Carolina. Bowles persuaded Dunmore that together they could enact Dunmore’s earlier idea of recruiting loyalists, Indians, and slaves to take West Florida and Louisiana from Spain.106