2.1. Raphael. The Triumph of Galatea, ca. 1514. Villa Farnesina, Rome. Fresco. Bridgeman Art Library.

PSYCHOGRAM AND PARNASSUS: HOW (NOT) TO READ A TWOMBLY |

So Twombly uses a kind of script? Certainly, but one that hardly has anything in common with it other than the name .… Yet it is a script, a transcription nevertheless, if not a mere psychogram spelling the command: Read!

—MANFRED DE LA MOTTE, “Cy Twombly” (1963)1

IN THIS PEREMPTORY call to “Read!” dating from the early 1960s, Twombly’s “psychogram” has already become identified with enigmas, scribbles, and quotations. Paradoxically, his script spells the command “read” rather than legibility. Despite de la Motte’s insistence, writing about Twombly has often resorted to the tropes and practices of reading. Twombly’s hard-to-read hand invites the viewer (sometimes tantalizingly) to decipher the meaning of his script. But deciphering is not quite right either. De la Motte again: “Here, reading is less deciphering and more allowing the eye to be captivated by sequences and passages, rhythmically teasing [them] out.” The effect, he suggests, is like that of a musical score, where a number may be an invitation to find another in the sequence, or simply stands in for the act of counting. Twombly’s composition becomes a kind of “open form,” inviting the viewer to participate in a temporal experience like that of modern music—a continuum in which any start or stopping-point can be chosen at random, and the act of listening itself creates meaning.

What kind of reading-practice is implied in this rhythmic teasing out of a Twombly? Musicological? Literary-critical? Art-historical? This chapter focuses on the varieties of reading provoked by Twombly’s art in relation to poetry, both in the form of quotation and as a figure for painting itself. It does so by concentrating on a group of paintings belonging to the early 1960s—a period of exuberant productivity that coincided with Twombly’s settling in Rome. These paintings have elicited exceptionally eloquent art writing, including literary criticism that bears on the question of how (or how not) to read a Twombly, as well as the artist’s own reading of the iconic visual texts that surrounded him in Rome.2 During the early 1960s, Twombly responded vividly (one is tempted to say, spatially) to Roman architecture, including frescoes that dramatically expand the confines of Renaissance and Baroque interiors. Robert Pincus-Witten calls this “a masterful solution to the dilemma of Abstract Expressionism during the advent of Pop.”3 The implication is that specific art movements demand ever-more progressive solutions. But like many artists before him, Twombly was confronted with a perennial problem—the “pastness” of art itself.4 Faced by the cultural consecration of Rome’s great art works, what possibilities exist for the new? Twombly’s dilemma is the challenge posed by art’s history since the Renaissance recovery of classicism, the nineteenth-century’s turn toward the idea of the avant-garde, and the modern as an end-of-the-line concept. Twombly’s response to Rome’s auratic cultural icons represents a sustained reflection on what it means to be “modern.”

Twombly’s immersion in Renaissance and Baroque art produces a newly luxurious palette. His paintings glow with sensuous color, lavishly or sparingly applied to large canvases. Paint conveys his visceral response to Renaissance artworks, along with the drama of Rome’s cultural “theatre,” past and present: not only its art and buildings, but its hectic street life, sexual encounters, and piazzas (The Italians, 1961).5 Painting after painting celebrates the carnality of desire—the heightened eroticism of gods and venial humans—in fluid and often scatological dramas that gesture toward what de la Motte summarizes as “Baroque pageantry.” Covering the surface of his canvases with pulsating episodes and passionately inscribed gestures, Twombly transforms the frescoes of Roman palazzi and Vatican stanze into a series of dazzlingly inventive citations. Renaissance and Baroque frescoes had used the physical features of Roman loggias and rooms to construct visual or narrative vistas that challenged the finiteness of space and time and brought the outside indoors. Acknowledging the accidents of architecture (the placing of windows, or clashes between perspectival construction and the viewer’s position), Twombly’s canvases are provocatively wall-like—flat rather than illusionistic. He writes his own name on the spaces of cultural icons that are installed in his own moment, rather than reverently consigned to their original art-historical place and time.

Twombly’s dramatic use of space, color, and perspectival allusion is particularly evident in paintings that invoke Raphael’s celebrated Roman frescoes: his Triumph of Galatea (1961), the Il Parnasso (1964), and his two versions of School of Athens (1961 and 1964). Decorating the loggia of the Villa Farnesina, Raphael’s Triumph of Galatea (1512)—based on a well-known poem by Angelo Poliziano—celebrates the (unstable) marriage of painting and ekphrastic poetry under the sign of love.6 (See figure 2.1.) Raphael’s Parnassus and School of Athens (1509–11), designed for the papal library of Julius II, reconcile the knowledge-traditions of poetry and philosophy under the signs of Apollo (god of Art and patron of libraries) and Athena, or Minerva (goddess of Wisdom). In Raphael’s Parnassus, the poets of the past sing, dance, and play their instruments. (See figure 2.2.) In School of Athens, the philosophers of antiquity read, write, demonstrate, and persuade. Raphael’s figures celebrate a Renaissance Humanist program designed to integrate classical and Christian learning—a program generally thought to reflect the Platonism of Giles (Egidio) of Viterbo, or perhaps of Tommaso Inghirami, Pope Julius II’s poetry- and pleasure-loving librarian.7 (See figure 2.3.) Each fresco ascends toward an apex of knowledge that is occupied, in Raphael’s Parnassus, by Apollo with the Nine Muses; and in Raphael’s School of Athens, by the figures of Plato and Aristotle in dialogue, holding the books by which they were best known (respectively the Timaeus and the Ethics).8 Between them, Raphael’s frescoes indicate the standing of love, poetry, and philosophy—and by implication, art—in Renaissance Humanist culture.

2.1. Raphael. The Triumph of Galatea, ca. 1514. Villa Farnesina, Rome. Fresco. Bridgeman Art Library.

Raphael’s Vatican frescoes represent the fourfold division of knowledge corresponding to the disciplinary organization of the Pope’s library: jurisprudence and theology face off against poetry and philosophy on opposite walls of the Stanza della Segnatura. Their unstated subject is painting, not just as a means to represent a particular Humanist knowledge-tradition to itself, but as an equivalent form of knowledge in its own right. Raphael depicts the poets and philosophers of the past as animated and absorbed by their activities, grouped dynamically rather than in static isolation, departing from medieval allegorical conventions.9 Twombly, in turn, displaces Raphael’s emphasis on the expressive, interactive human body (singing and dancing, studying and teaching) with a body-based art predicated on leaping anti-figural forms and gestural mark-making. In response to the fourfold disciplinary division of Raphael’s frescoes, Twombly makes visible the fifth, occluded branch of knowledge: painting. His titles do more than cite the Raphael frescoes—he rereads and transforms them. In doing so, he updates ways of knowing implied in frescoes that, today, themselves often require to be “read” with the help of scholarly accounts of Renaissance learning inaccessible nonspecialist viewers.

2.2. Raphael, Parnassus, 1510–11. Stanza della Segnatura, Vatican Museums and Galleries, Vatican City, Rome. Fresco. Bridgeman Art Library.

Twombly’s paintings can be read as a form of thinking “through” (not just about) painting—a modern equivalent of the poetic and philosophic program that informs Raphael’s frescoes. They invoke both the conditions of their own making and the disciplinary formation of art history. A series of influential accounts of Twombly’s paintings reveal the pervasiveness of the trope of reading in art writing, especially writing that defines itself against more traditional art-historical narratives. In its longstanding role as Parnassian supplement, poetry invokes what philosophy is supposed to know and consecrate: truth, univocality, elevation. Presiding over the Stanza della Segnatura, the figure of Apollo harmonizes an old quarrel—not just Plato’s “ancient quarrel between poetry and philosophy,” but the anti-mimetic quarrel between philosophy and painting. Engaging a long-running dispute, Twombly’s paintings pose questions about art practice and the history of art as forms of knowledge.

2.3. Raphael, School of Athens, 1510–12. Stanza della Segnatura, Vatican, Rome. Fresco. Bridgeman Art Library.

né’l vero stesso ha piú del ver che questo;

e quanto l’arte intra sé non comprende,

la mente imaginando chiaro intende.

[truth itself has not more truth than this; whatever the art in itself

does not contain, the mind, imagining, clearly understands]

—ANGELO POLIZIANO, Stanze, Book I, stanza cxix/11910

Raphael’s Triumph of Galatea (1511–12), decorating the loggia of Agostino Chigi’s Villa Farnesina, across the river Tiber in Trastevere, was commissioned to celebrate the marriage of a wealthy papal banker to his young bride. It shares the marriage theme with other frescoes in the villa: the Council of the Gods and the marriage of Cupid and Psyche on the ceiling of the Loggia of Cupid and Psyche (painted by Raphael’s workshop), and the marriage of Alexander and Roxana in the Chigis’ marital bedroom (painted by Raphael’s friend, Sodoma).11 In the Loggia of Galatea, the sea-Nereid Galatea stands on a paddleboat seashell, ignoring Polyphemus, her clumsy one-eyed consort (Sebastiano del Piombo’s lowering giant) on the panel next to her. Despite her heaven-turned gaze, Galatea’s triumphant progress sets fleshly love swirling around her. Her cockleshell boat is pulled along by two dolphins, symbolizing virtue; one of them gobbles a renegade sensualist octopus. Winged cupids armed with bows and arrows flutter in the clouds above; brawny tritons and seahorses make off with Nereids; tritons blow their conches on each side of the Galatea’s Triumph. The wave-borne cupid in the foreground looks backward, like Galatea herself, while guiding the harnessed dolphins to their destination. Peachy, half-clad bodies combine muscularity and buoyant upward movement. The lovely blue of a cloud-streaked sky rises above a flat sea.

Poliziano’s late quattrocento Stanze Cominciate per la Giostra del Magnifico Giuliano de’ Medici (1476–78)—a Platonic conceit designed to flatter a Medici nobleman from a family famous for both its palaces and its art collection—describes Cupid overcome by Minerva.12 Its ekphrastic description of the decorations forged by Vulcan for Venus’s palace provides an elaborate poetic account of how art embellishes architecture in the service of love.13 The word “stanza” in Poliziano’s title (meaning both the verse or “stanza” of a canzone, and “room”) understands classical allusion as simultaneously formal and spatial. Poliziano’s description of Venus’s Vulcan-forged palace also provided literary sources for Botticelli’s Birth of Venus (ca. 1484–86) and Venus and Mars (ca. 1485); Botticelli follows Poliziano’s description of Venus wrapped in foam and “carried on a conch shell, wafted to shore by playful zephyrs” (“da zefiri lascivi spinta a proda, / gir sovra un nicchio”; I. xcix/99). Poliziano emphasizes the truth-to-life of foam and sea, conch shell and blowing wind (“Vera la schiuma e vero il mar diresti, / e vero il nicchio e ver sofiar di venti”; I. c/100). As in Botticelli’s Birth of Venus, Raphael’s seashell would have been understood as a reference to the vulva of the sea-born beauty it brings to shore. Poliziano’s stanzas describing Vulcan’s mythological decorations—rapines and couplings (including Leda and the Swan)—are book-ended by the birth of Venus and the triumph of Galatea. This last was the subject chosen to decorate Chigi’s architectural epithalamium: a palace of art and love, lavishly disguised as a pastoral retreat just across the Tiber, yet within a stone’s throw of urban Rome.

Poliziano’s Stanze includes the grotesque figure of Polyphemus, a hairy, grief-stricken lover. His Cyclopean attributes (bristling locks, dog, shepherd’s pipe) make him a bucolic foil to Galatea’s half-naked beauty, as she is pulled along by her shapely dolphins, surrounded by cavorting sea creatures: “one spews forth salt waves, others swim in circles, one seems to cavort and play for love” (“qual le salse onde sputa, e quai s’aggirono, / qual par che per amor giuochi e vanegge”; I. cxviii/118). Poliziano’s poem contains another voyeur: the cuckolded artist, Vulcan. The palace he creates for Venus is decorated by the intertwined acanthus, roses, myrtle, and other flowers that are echoed in the painted swags on the ceiling and walls of the Villa Farnesina, along with the motif of birds—so realistically depicted, writes Poliziano, “that one seems to hear their song plainly in one’s ears” (“che il lor canto / pare udir nelli orecchi manifesto”; I. cxix/119). Yet even these trompe l’oeil effects demand the supplement of imagination: “whatever the art in itself does not contain, the mind, imagining, clearly understands” (“e quanto l’arte intra sé non comprende,/ la mente imaginando chiaro intende”; I. cxix/119). Imagination supplies what Vulcan’s artifice lacks, just as poetry supplements Raphael’s two-dimensional frescoes.

Poliziano’s Stanze uncovers a scene of undecidability. Does painting lack what poetry alone can supply through the imagination—or must poetry call on painting to realize what it attempts to describe? Poliziano’s location of the origin of art in Vulcan’s mythological workshop sets up an endless regress. Like Chigi’s villa, Vulcan’s palace publishes an imaginary scene of consummation: the room containing Venus and Mars, surrounded by cupids whose fanning wings inflame Venus’s heart and augment her pleasure, while Mars lies exhausted by their love-bouts (“Cupido ad ale tese … e pur co’ vanni el cor li accese”; I. cxxiv/124). The formal container, the “stanza,” invokes an imaginary room dedicated to the consummation in Vulcan’s mind’s eye as he schemes to capture the lovers in flagrante delicto, like the jealous Polyphemus. The erotic object can never be fully possessed; but neither can the desiring imagination let it go. Desire drives the mobility of endless substitutions, just as erotic art fans the imagination with the rhythm of its cupid-wings and the beat of poetry. “[T]he mind, imagining” (la mente imaginando) takes pleasure in the enjoyment that both poetry and art withhold—tantalized by a dilemma that Giorgio Agamben describes as “the enjoyment of what cannot be possessed and the possession of what cannot be enjoyed.”14

One of Barthes’s two well-known essays on Twombly is titled “The Wisdom of Art.” In his 1979 essay, Barthes nostalgically associates Twombly’s “Mediterranean space” with Valéry’s “‘vast rooms of the Midi, very good for meditation.’”15 Valéry provides the concept of an imaginary rectangle or room filled by the artist, the “Rare Rectangle” that Barthes associates with Twombly’s canvases: “Basically, Twombly’s paintings are big Mediterranean rooms, hot and luminous, with their elements looking lost (rari) and which the mind wants to populate.”16 This empty room—an empty stage—contains only the implements and materials for painting and drawing, the alchemical materia prima that preexists the division of meaning. When Barthes calls a Twombly canvas rari (meaning “emptied out”), he has in his mind not only the artist’s emptying out of the picture (“according to the principle of the Rare, that is, of spacing out”), but also the activity of the viewer’s imagination in filling it in.17 Barthes’s “absolute spaciousness” is at once room, canvas, and overarching sky: “the depth of a sky in which light clouds pass in front of each other.” These airy heights produce what he calls (adopting Bachelard’s term) “an ‘ascentional’ imagination”—a form of disembodied bliss or jouissance: “I float in the sky. I breathe in the air.”18 Porous, emptied out, the luminous spaces of Twombly’s canvases are defined both by their capaciousness and by their elevation. They induce in Barthes a kind of writerly “high.”

Barthes reads Twombly’s mythological titles—his Birth of Venus (1962), for instance—as cultural theater (“a kind of representation of culture”).19 (See figure 2.4.) Twombly’s Venus floats on a sea of foam, half in and half out of the horizon-line—pinkly multibreasted, fleshly, biomorphic, and aquatic. As in Poliziano’s poem or Botticelli’s Birth of Venus, erotic art is born from the ocean-spill of semen.20 Despite their performativity, Barthes suggests, Twombly’s titles proffer “the bait of a meaning.” He writes aphoristically, “Meaning sticks to man.”21 While frustrating the quest for analogy, Twombly’s paintings still produce the effect of meaning rather than nonmeaning. To illustrate the circulation of cultural texts, Barthes again invokes Valéry, this time his poem “Naissance de Venus,” citing its joyous “‘effect’: that of arising from the sea” as Venus comes ashore surrounded by “L’eau riante, et la danse infidèle des vagues.”22 The convergence illustrates Barthes’s so-called Twombly “effect,” that is, “the very general effect which can be released, in all its possible dimensions, by the word ‘Mediterranean.’”23 Filling the empty spaces of Twombly’s painting with the activity of his own imagination, Barthes drifts between desire and memory: “I know the island of Procida, in the bay of Naples, where Twombly has lived.… There, calmly united, are the light, the sky, the earth, the accident of a rock, an arch.” Twombly’s Bay of Naples (1961) becomes a representation of the Barthesian “Mediterranean effect” (effet or “aesthetic impression”)—“this whole life of forms, colors and light which occurs at the frontier of the terrestrial landscape and the plains of the sea.”24

2.4. Cy Twombly, Birth of Venus, 1962. Rome. Oil paint, lead pencil, wax crayon on canvas, 66⅞ × 82¾ in. (170 × 210 cm). Collection Jung, Aachen. © Cy Twombly Foundation. Photo courtesy Gallery Heiner Bastian.

Barthes’s euphoria is worth pausing over. Even as he specifies the recollected features of this mythological, poetic, and geographical meeting-point—“this void of the sky, of water, and those very light marks indicating the earth (a boat, a promontory) which float in them”—he is immersed in the element of quotation, invoking first Valéry and then Virgil’s “apparent rari nantes” (“Here and there they are seen swimming …”), perhaps the source of his term rari.25 The after-images of a specific landscape are buoyed up by allusions to French symbolist and Virgilian poetry. Nothing sea-borne in Twombly’s Bay of Naples is definitively represented except the pink of the sky, an exquisite blue-gray-aquamarine or palest mauve-gray, the leap of scarlet and flash of gold, a shadow of scribbled activity that seems to invoke bodily mingling or a sea-birth between waves and sky. A shelf indicates promontory, metric, or horizon amid a flurry of shadowy markings; flesh-pink triangles, breasts, and throbbing pulsations of pleasure evoke ocean-born bliss, in which bodies and landscape are suspended indeterminately between sea and sky. Read as Barthes reads it, Twombly’s painting becomes a license for Barthesian free-association.26 For Barthes himself, “the ‘subject’ of the painting is also the person who is looking at it: you and me.”27 “You and me”—viewer, reader, writer—merge indistinguishably into a combined Mediterranean subject-effect: Twombly/Barthes. (See figure 2.5.)

2.5. Cy Twombly, Bay of Naples, 1961. Rome. Oil paint, oil-based house-paint, wax crayon, lead pencil on canvas, 95¼ × 117⅝ in. (241.9 × 298.8 cm). Menil Collection, Houston, Cy Twombly Gallery. © Cy Twombly. Photo Hickey-Robertson, Houston.

Twombly’s painting contains only the apparent naturalness of representation: “the blue of the sky, the gray of the sea, the pink of sunrise.”28 In this quasi-referential context, the graphic sign is registered as a shock, “a jolt, an unsettling of the naturalness of painting.” What Barthes names as an unsettling jolt—“the repulsive use of written elements”—confronts viewers head-on with the nonreferential aspects of Twombly’s painting. Graphism is at odds with the “dawnlike peace of its spaciousness,” paradoxically enlisting the painting in “a fight against culture, of which it jettisons the magniloquent discourse and retains only the beauty.”29 Barthes understands Twombly’s subversive “art of the jolt” (the intrusion of writing) as the ingredient that differentiates his aesthetic from the Apollonian luminosity of the classical past. Above all it is “strokes, hatching, forms, in short the graphic events [that] allow the sheet of paper or the canvas to exist, to signify, to be possessed of pleasure.” Signification produces a kind of white noise, “a very faint sizzling of the surface” (“un grésillement très tenu de la feuille,” or “very slight crackling of the sheet”).30 This signifying, pleasureable, noise-making canvas is the one before which Barthes (“the subject of pleasure”) can only exclaim: “‘How beautiful this is!’ and say it again,” before falling mute, tortured by the inadequacy of language. Hence the impulse to imitate: “Do you feel like imitating Twombly?”31 For Barthes, “The Wisdom of Art” is not what art knows, or what it says, but what it does and what it makes one want to do. Writing produces the urge to paint: painting produces the urge to write. The white noise of the canvas is the writerly (“scriptible”) sound of jouissance—the noise made by Barthes’s own blissfully immersive imaginary.32

In the room in which they are hung in the Twombly Pavilion at the Menil, Twombly’s Bay of Naples faces his Triumph of Galatea.33 (See figure 2.6.) Each painting is anchored at the upper right by a small but prominent pair of circles, densely painted in flesh-pink and, in Triumph of Galatea, outlined in vivid blue.34 These visual punctuation marks—the throbbing pulse of desire?—emphasize the height of each painting, which also extends laterally in Triumph of Galatea, as if Twombly had taken the left-to-right movement of Raphael’s upright fresco and unfurled it in a rising action across his own canvas. Festooned across the upper part of Triumph of Galatea is a loosely painted swag of peach and fleshly pink—airborne activity that seems to culminate in the multiple breasts of a nascent “Birth of Venus,” half-obscuring the word “PARNASSUS.” Poetry is in the air. Scattered across the canvas, other ellipses and punctuation marks, paler or darker pink, red or brown, form discrete pulses of desire amidst flurries and swirls of painterly activity and leaping figures. Something is being borne (or born), as if from the intermixture of sea or sky indicated by patches of pale blue. Horizontal “shelves” to the lower left, along with a peachy phallic pointer, provide horizontal anchors and directionality. A little to the right of center, a swirl of entangled peach and pink paint-marks suggests the dynamic fusion of a sexual encounter, perhaps the companion-event to the flying festoon above.

The leaping rhythms of Twombly’s Triumph of Galatea transform the creamy-peach and dark reds of Raphael’s epithalamium into a painterly consummation. Twombly celebrates paint as if it were the liquid fusion and mingling of flesh, blood, and body-fluids. Perhaps in a reminiscence of Raphael’s muscular seahorses and gray porpoises, scattered gray-green markings weight the painting’s lower margin. A series of orange, upwardly mobile curving figures spring up from the lower edge, graduating from golden peach and flesh-pink to deeper reds and messy browns.35 A sequence of graphic events that begin on the left-hand margin as a wisp of thought—a white cloud or a dream, a trailing sea organism or a fishtail, a scribbled X-marked mons veneris, the rhomboid of a numbered sequence or page—shadows a release of unbound polymorphic pleasure: not the triumph of Galatea, but the triumph of paint. Twombly recapitulates Raphael’s energetic figures (the fishtails, porpoises, and hooves beating the waves) in the upward impulsion of his own painting. Barthes describes its mood as “euphoric” (from the Greek, eu-pherein): literally well-borne-up—here, by the marriage of Eros and painting. An inspired and sumptuous rereading of Raphael’s fresco, Twombly’s Triumph of Galatea implies that the buoyancy of his art is inseparable from the visceral mess of paint—abstract marks on the canvas that refer only to themselves, the ultimate sign of pleasure.

2.6. Cy Twombly, The Triumph of Galatea, 1961. Rome. Oil paint, oil-based house paint, wax crayon, lead pencil on canvas, 115⅝ × 190⅜ in. (294.3 × 483.6 cm). Menil Collection, Houston, Cy Twombly Gallery. Gift of the Artist. © Cy Twombly Foundation. Photo Hickey-Robertson, Houston.

II. “THE DANCE IS QUITE ANOTHER MATTER”

The dance is quite another matter.… It goes nowhere. If it pursues an object, it is only an ideal object, a state, an enchantment, the phantom of a flower, an extreme of life, a smile—which forms at last on the face of the one who summoned it from empty space.

—PAUL VALÉRY, “Poetry and Abstract Thought” (1939)36

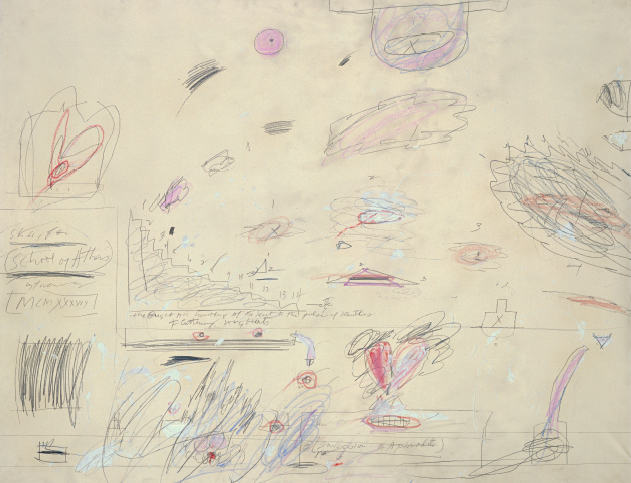

Valéry’s definition of poetry—“actions whose end is in themselves”—speaks (like Barthes’s aesthetic) to the pleasures of the “empty space” from which it plucks imaginary forms.37 Philip Fisher’s “Thinking through the Work of Art,” in Wonder, the Rainbow, and the Aesthetics of Rare Experiences (1998), uses the dance metaphor to think “through” (that is, by means of) a Twombly painting.38 His reading of Twombly’s Il Parnasso (1964) focuses on the “field of details” and “small-scale events” that make up what he defines as subcanvases within its larger design (comparable to the individual sections of plaster, or giornate that compose Raphael’s frescoes).39 (See figure 2.7.) Fisher, however, reverses the expected order of citation and “original.” Instead of starting with Raphael’s fresco, he turns to it at the end as part of a premeditated critical strategy. His aim is to show that Twombly’s “syntax” of painting refuses to be reduced to its visual inter-text, let alone viewed as a “translation” of Raphael’s fresco. Instead, he suggests, “the painting itself is instructing us in how to look at it with prolonged attention.”40 This is what his careful pedagogical reading teaches us. Once again, the trope of reading surfaces in the context of “reading” a painting by Twombly—here, in order to define its difference in terms of line, color, and abstraction.

2.7. Cy Twombly, Il Parnasso, 1964. Rome. Oil paint, wax crayon, lead pencil, colored pencil on canvas, 80¾ × 85⅞ in. (205.1 × 218.2 cm). Collection Mr. and Mrs. Graham Gund. © Cy Twombly Foundation. Photo courtesy Gallery Heiner Bastian.

Fisher’s answer to the question he sets (“How does the work teach us to read it?”) lies in focusing on the painting’s individual components—in effect, a technique of “close reading.”41 We are taught by the painting itself to enjoy its complexity and detail by means of an incremental sequence of events, starting on the top line of the painting, as it were, and reading from left to right, much as one might read a poem or a written page.42 Fisher’s reading-lesson pays minute attention to “energy” and “pulse,” almost as if the canvas were sentient: “The basic unit of the surface is a little free-standing burst of energy.… We see a line, a dab of paint, a splash, a splatter, a scribble, a scratch, a mark.” The record is bodily, febrile, momentarily sensitive to fleeing sensations: “each gesture is in essence a thrill, a vibration, a shudder or rapid pulse.” The surface is alive with short-lived tremulousness (compare Valéry’s phantom flower or summoning-up of a fleeting smile): “… frissons, shivers, a thrill or ripple of muscular sensation, a first sip of unexpectedly cold wine, a shooting star, a gesture of great delicacy seen across a room, a brief smile.”43 Falling in love, again.

Fisher’s exquisite evocation of Il Parnasso summons up the aesthetics of transience, events briefer even than “the brief or transient things that Keats or Shakespeare thought transient.” Like music, or taste, transient beauty constitutes “part of the nervous life of surprises”—“the entry of the flute in a symphony, or the first bite into an unexpectedly perfect summer peach.”44 What is it, exactly, that evokes such delicious synaesthetic experience? Fisher’s inquiry pertains especially to his question about “the limits of the tiny event.” He asks: “How small can a detail be and still be sensuous?”—“How small can a trace of color be and still be voluptuous?”45 His answer to this question (never too small!) lies in the cumulative effects of small-scale units of meaning that are analogous to letter, word, phrase, sentence, or paragraph in a literary text, as each individual episode or subcanvas builds on another to create an intelligible syntax. Fisher’s poetic metaphor for this combinatory intelligibility is a pair of dancing figures: in other words, the familiar form of the literary epithalamium. The figures in this painting are in love, and (like Fisher) in love with a specific idea of aesthetic beauty.

Fisher’s dance is his metaphor for the play of line. The white line with its blue lining that enters from the left—the “top line” of Twombly’s Il Parnasso (read from left to right)—dances its way across the canvas toward successive encounters and entanglements with other lines. Thus “a line reaching back across itself, a gentle, curving, pacific line, like a figure asleep” is awakened into life by newly introduced color-elements and forms. The encounter is that of self and other, “a mating dance of female and male halves, the white … brought to a pitch of energy in an antagonistic encounter with things not itself.”46 Fisher codes this “highly civilized” mating ritual (an encounter with difference) as sexual difference—the meeting of female and male; the dance has its own excitement, climax, and repose. Bit by bit, Twombly’s “dancelike pair of figures” (“dancelike couples,” “face-to-face couples,” “coupled, figural forms”) are endowed with near-human attributes: “energy, bodily intelligence, and upright position.” They acquire “what we might call personhood, or personlike reality.”47 They become, in short, personifications. Trained to find intelligibility in such coupled figures and their relation to other pairs, Fisher suggests, we come to understand and appreciate the painting’s “rich syntax” as each couple replicates gendered forms of self-difference.48 It is as though the painting produces (as well as mirroring) the heterosexual coupling celebrated by Western art.

Fisher’s close reading of Twombly’s Il Parnasso culminates with an episode that he singles out, evocatively, as “one of the most beautiful, sensuous pairings of two energetic figures, one black and the other a luscious pink orange figure, both musical, agitated, alive with erotic energy and with mirroring excitement.”49 But he is too canny not to question his own vocabulary of gendered, heterosexual, dancing and mating couples. Why the love story? Such “micro-scripts,” he suggests, are specific to a culture that legitimizes seeing dabs of paint in terms of “any language of persons and relationships,” while privileging the universality—the allegory?—of the heterosexual plot.50 But it would be a mistake to see Fisher’s narrative of “voluptuous pairings” as unself-consciously succumbing to a gendered paradigm. The story he reads is preassigned both by and for Twombly himself. Inscribed on Twombly’s Parnassian canvas, labels identifying Sappho and Apollo allow us to recognize just what kind of dance this is—Eros in the service of Art.51

Fisher recognizes Sappho as “the figural climax of the progression.”52 Twombly’s Il Parnasso announces itself as a version of Raphael’s fresco, where Sappho—Plato’s Tenth Muse and the first poet of lyric love—occupies the left foreground with her scroll, paired with Pindar’s ancient choric poet on the right.53 Fisher’s ascent of Parnassus exactly follows Raphael’s construction of Neoplatonic poetic tradition: starting from Sappho and Pindar, Greek lyric attains to the heights of Apollonian harmony. In Fisher’s words, “led on by captured attention, drawn on by pleasure,” the viewer moves from the secular to the Apollonian and thence to the Neoplatonic sublime: “The sky of the painting belongs to the gods.”54 The poetic climax that creates such “exquisite effects of elegance and delight” is associated with the figure of Apollo, surrounded in Raphael’s fresco by the dancing Muses, and in Twombly’s painting by a scribble of blue and green, his name, and the word “Muses.” Fisher—and by implication Twombly—is entirely accurate in reading Raphael’s program as representing the ascent of Eros toward celestial love.55 Thinking “through” Twombly, Fisher recognizes the underlying plot of Raphael’s Parnassus. Apollo—god of music, poetry, and (in Neoplatonic philosophy) divine illumination—signifies the “mating” of secular and heavenly love in the version of Renaissance Humanism on which Raphael’s fresco draws; a version that permitted ancient and modern poetry to stand alongside each other, in harmony with both ancient philosophy and Neoplatonic Christianity.

The musical analogy of Raphael’s Parnassus—Sappho’s harp, Apollo’s lyre, the singing and dancing Muses—underwrites Fisher’s dance metaphor. His finely attuned reading responds, in fact, to the finely tuned relation between a pair of visual intertexts dancing together. In his reading, Twombly’s erotic celebration of art pairs off with Raphael’s allegorical representation of poetry. The pedagogical ruse that a reading-primer is built into Twombly’s Il Parnasso allows Fisher to suspend what he refers to as “the source hunting of traditional art criticism.”56 Yet this temporary suspension implies, albeit unintentionally, that the only alternative to Fisher’s “blind” reading (as we now see, a reading shaped and informed from the outset by Raphael’s Parnassus) is the relation of a painting to its source-text. This is surely not how artists themselves regard relations between works set in dialogue with each other—nor need art history be confined to “situating Twombly’s painting within a tradition of precedent works.”57 Fisher tellingly dismisses the idea of a coded visual translation (“a Morse code version of a Shakespeare sonnet”).58 His own reading, by contrast, is designed to uncover what one painting “knows”—how it thinks—about another; and hence Twombly’s inscription of difference. This difference, however, is primarily painterly—analogous to the swerve between source-text and translation as the “original” is left behind and the new work enters a different culture.

The effects of allegory are pervasive in the story Fisher tells. When he proposes that “the idiom of abstract art is itself the spiritualization, the etherealization of earlier realistic idioms,” he introduces what is in essence an allegory of modern art, along with the implication of a progressive telos (the “ascent” of modern art from realism to abstraction).59 Such a narrative might be called the “ascentional” theory of art history (pace Barthes), as each successive movement ascends on the shoulders of the previous one, in a trajectory that combines technical with aesthetic advance. This, in fact, is just how the late nineteenth-century founders of the discipline did envisage the History of Art—as the historical progression of one style succeeding and improving on another, in step with cultural and technological change.60 It therefore becomes possible for Fisher to understand Il Parnasso’s poem-like complexity and playful detail as aspirational: “a monumental landscape depicting the paradise of art which each artist, in the act of painting it, claims to join by taking his place among the names in paradise: Sappho, Homer, Dante, Twombly.”61 In this account, the writerly painter, Twombly, signs on to a literary gradus ad Parnassum when he puts his own signature in the outline of Raphael’s window.

At this point, however, I want to go in another direction and see in Twombly’s self-signing a potential opening of a more radical kind—an invitation to consider the constitutive moment in the discipline of the history and practice of art whose origins are often thought to lie in the Renaissance “invention” of perspective.62 Taking my cue from Barthes, one might see in Twombly’s rectangle, not a window, but Alberti’s figure of a window; not a representation of the shuttered opening that punctures the wall of the Stanza della Segnatura, but Barthes’s “jolt” of writing’s antagonistic intrusion into the illusionistic field of painting.63 The window-sign, often used by Twombly to signify the picture within his paintings (a mise en abyme), goes back to Alberti’s treatise On Painting (1435).64 For Alberti, the picture window is both the surface on which the artist paints and the aperture through which he sees (“an open window through which the subject to be painted is seen”).65 But this window is not really a picture-window. The window is a sign of representation itself: a sign, that is, of the tension between illusionism on one hand, and on the other, the flat, two-dimensional surface of the painting. It is therefore key to any consideration of painting’s capacity to reflect philosophically on the conditions of its own making and knowing.

The window of the Stanza della Segnatura is often photographed shuttered against the light. Dispelling any association with an imaginary Parnassian landscape, Twombly’s signature announces his painting as a reseeing of Raphael’s monumental hill of art as a flat wall interrupted by an awkward window. Il Parnasso riffs on clearly recognizable features of Raphael’s Parnassian Hill: the Castalian Spring (vivid loops of blue); its three laurel trees (loose green scribbles and paint scrawls); its arching composition around the squared-off outlines of a rectangular aperture. The exquisite line that Fisher describes so lyrically recapitulates the cloud-forms that enter from the left and sail across Raphael’s celestial sky beneath its key-pattern arch. Twombly’s figure-of-eight casually laid over itself—his languorous line of beauty—evokes graphic mastery deliberately eschewed. Fisher is entirely accurate when he observes that “[t]he figure marked Apollo near the upper center is a climax of spiritualized matter, an exquisite trace of the high-energy action of art.”66 In its own way, Twombly’s painting is a record of art’s energetic action: his action-painting is defined against Renaissance high culture, making visible what it conceals—the materiality of the medium and the sheer contingency of the physical support.

In related paintings that invoke Apollo or the Muses—Twombly’s Untitled (1963) series, or his sequence of Muses (1963)—their names are inscribed within or above a rectangular frame, perhaps the sign of book or page.67 The window-aperture in the wall of the Stanza della Segnatura has been associated by at least one commentator with the Corycian cave, “the best-known and most beautiful cave of Mount Parnassus.”68 A cave provides Western philosophy’s most famous allegory of the deceptiveness of visual forms. In Plato’s allegory of the cave, the primary light of the sun is the only source of true knowledge—truth itself—as opposed to the shadowy images cast by firelight. If indeed Raphael meant to remind his Renaissance viewers of Plato’s cave, then the fresco contains yet another scene of radical undecidability: Raphael’s Parnassian landscape ironizes painted images as illusory, even as it insists that art gives access to the marriage of Apollonian and Neoplatonic truths. An even longer retrospect posits the primal scene of painting as taking place in a cave, with the tracing on a wall of the outline of a human hand. This vista of infinite regress enfolds the entire field of art history’s longue durée in Twombly’s revisioning of Raphael’s Parnassus. The painting’s dream-navel reaches down into the unknown.

What Fisher calls “recognition” in painting is another name for the viewer’s capacity to make sense of signs: an outline on a wall, marks on the page; a name or a signature. Fisher asks: “How do we get from humble scribbles to poetry or even to the name Sappho?”69 What is the origin of poetry? What is the origin of painting? How does a scribble become a word, a name, or an inspiration? Raphael’s Parnassus offers a Renaissance version of the history of poetry in the historical time of its own painting: the renewed interest in Sappho; the recent publication of the Homeric Hymns with their dedication to Apollo; the Italian poets of the preceding centuries (Dante, Petrarch, Boccaccio, Ariosto).70 The painted grisaille panels beneath Raphael’s Parnassus allude to the recovery of classical literary culture (Homer and Virgil) for Renaissance poetic tradition.71 By contrast, Twombly’s Il Parnasso offers a counter-history of painting, situated after the Modernist break with allegory and mimetic representation, located in its own time, prominently signed with the artist’s name, date, and place (“Roma”). Twombly’s Il Parnasso says, not just “Read!” but “Read the writing on the wall”—the marks made by the painter’s hand on a flat surface that declares itself not to be a wall, but a canvas.

The loggias of Raphael, the huge paintings of the School of Athens, etc., I have seen only once. This was much like studying Homer from a faded and damaged manuscript. A first impression is inadequate; to enjoy them fully, one would have to look at them again and again.

—J. W. GOETHE, Italian Journey (1786–88)72

Goethe’s response to Raphael’s School of Athens—“much like studying Homer from a faded and damaged manuscript”—invokes the trope of reading that has haunted Raphael’s fresco from Goethe’s time to ours: how can it be read when so much knowledge has been lost? The question is compellingly posed by the classicist Glenn W. Most when he invokes Goethe’s puzzlement at the start of his essay “Reading Raphael: The School of Athens and its Pre-Text.”73 Most’s term, “lacunose,” draws attention to the enigmatic status of Raphael’s representation of Neoplatonic Humanist philosophy (“entirely without precedent in the tradition of European art”).74 He frames his inquiry into the visual and textual sources for Raphael’s representation of philosophy with larger questions that remain relevant for contemporary viewers: not only what it means to reconstruct a historically plausible scheme of interpretation, but also how and whether such understanding enriches our pleasure—and why reading School of Athens as an “illustration” of a hypothetical intellectual program might not do so.75 Despite its appearance of transparent legibility, Most asserts, Raphael’s fresco “resolutely withdraw[s] from our attempts to read it.”76 A painting full of images of books resists being read.

Rather than approaching Raphael’s School of Athens through its intellectual background, I want instead to approach it by way of a figure in the foreground: the brooding figure traditionally known as Il pensieroso.77 (See figure 2.8.) The stance of this pensive man uncannily anticipates Rodin’s Penseur—except for one important difference: pen in hand, he writes as he thinks (his handwriting clearly discernable on the paper beside him). A later addition to Raphael’s fresco, the man of thought is identified with the figure of Heraclitus, brooding on the creation of the world. Both in physical appearance and in style, Raphael’s Heraclitus is easily recognized as Raphael’s admired rival, Michelangelo—at work on the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel while Raphael was working on his frescoes for the Stanza della Segnatura. An eccentric and melancholy figure reputed to sleep in his boots, Michelangelo brings poetry to the forefront of Raphael’s fresco as he pens—what? He is plainly in the throes of composition, searching for the right word or phrase, or perhaps for the next line of what I want to imagine as a sonnet. Although most of Michelangelo’s sonnets post-date Raphael’s School of Athens, he was already known as an accomplished poet. His extended sonnet-sequence addressed to a male lover—preceding Shakespeare’s by half a century—were reclaimed for late nineteenth-century aestheticism by John Addington Symonds, whose 1878 translations undid the censorship of previous editors.78

2.8. Raphael, School of Athens, detail (Michelangelo and Pico della Mirandola), 1510–11. Stanza della Segnatura, Vatican Museums and Galleries, Vatican City, Rome. Fresco. Bridgeman Art Library.

Michelangelo complained that Raphael had not just learned from him but also plagiarized his Mannerist style. But the figure of Il pensieroso is manifestly an affectionate tribute by one papal painter to another. The only philosopher in Raphael’s School of Athens to be realistically portrayed, he wears contemporary clothes. His workman’s smock, turned-down boots, knotted knees, and veined hands single him out as a manual worker despite the quill pen he holds.79 Leaning against the massive block of stone from which (he claimed) his chisel could free the human figure within, he is oddly detached from Raphael’s otherwise symmetrical foreground.80 His expression is that of an inward-looking solitary, lost in thought as he turns away from the animated groups engaged in the sociable pursuit of learning. The effect is to frame Raphael’s idealized depiction of past philosophers in the contemporary moment of its painting, date-stamping the scene of the Athenian academy with the time-present of the defining cultural projects of Julius II’s demanding papacy. Michelangelo himself had complained of his drudgery when he quarreled with the Pope a few years before.81 Nor is this all. Raphael lays claim to his own graceful style by emphasizing its contrast with Michelangelo’s strenuous “creation.” He can paint like Michelangelo if he wants (so this figure of absorption implies), but he chooses to paint otherwise.

Raphael’s distinguishing aesthetic, his sweetness, is nowhere more clearly seen than in the white-robed youth (usually identified as Pico della Mirandola) who catches the viewer’s eye as he floats like an emanation of serene beauty behind the Pythagorean group clustered at the lower left. His lovely look has been associated with the Pope’s favorite nephew, Francesco Maria della Rovere, Duke of Urbino, as well as the strikingly beautiful and beloved youth named Agathon in Plato’s Protagoras—a text that been suggested as the inspiration for Raphael’s design.82 The only other figure who looks directly out of the fresco in this way is Raphael himself, gazing mildly from beside a pillar at the extreme right of the painting, next to a companion-painter usually identified as his friend Sodoma (Giovanni Bassi).83 Raphael inserted other contemporary likenesses—for instance, his mentor Bramante, then engaged in the redesign of Saint Peter’s, as the geometer Euclid surrounded by his students on the right. The architecture of Raphael’s spacious barrel-vaulted basilica in School of Athens has been attributed to Bramante’s influence, as well as that of Rome’s recently recovered archeological ruins.84 Along with figures associated with Pope Julius II’s aesthetic and architectural projects, Raphael includes a portrait of the Pope’s librarian Tommaso Inghirami, as a plump Epicurus crowned with vine-leaves, book propped on a pillar. Nicknamed “Fedra” for his adolescent starring role in a dramatic performance of Seneca’s Hippolytus, Inghirami is a plausible source for the fresco’s entire pictorial program.85

The barrel-vaulted ceiling of Raphael’s Renaissance-style antique basilica soars above elevated niches, containing statues of Athena with her terrifying Gorgon shield and Apollo with his lyre.86 Similar sculptures of famous men (uomini famosi) line the recession of pillars behind the central group of philosophers, jutting into the imaginary space of arcade or “nave.” The interactive groups of philosophers in School of Athens are installed in their prehistory: a mythical past, turned to (painted) stone, strategically placed above trompe l’oeil bas-reliefs representing the transformations wrought by the two presiding divinities on anger, lust, and reason (Plato’s redeemable attributes of the human soul).87 Raphael was not a sculptor himself, and the extent of this pictured sculptural decoration is unusual in his work. It has been suggested that his ideas about the sculpted human figure in School of Athens derive from none other than Michelangelo, whose designs for the projected tomb of Julius II had been suspended while he worked on the Sistine Chapel. The exaggerated torsion of Apollo’s pose—one hip and shoulder raised, leaning on a tree trunk with his foot resting on a block—recalls the contrapposto stance of Michelangelo’s male sculptures.88

Raphael’s multilayered, densely signifying design simultaneously realizes and derealizes Humanist philosophy. His philosophers and scholars come to life as recognizable, three-dimensional contemporary portraits. This is not just because of Raphael’s departure from earlier pictorial conventions, but also because they contrast with other forms of representation depicted in his fresco: sculpture, basrelief, and—above all—books. Prominently displayed at the apex of Raphael’s intellectual design are two books, Plato’s Timaeus and Aristotle’s Ethics; Plato points toward heaven, while Aristotle gestures toward the world. On one hand, a highly theorized account of creation by a benign demiurge compatible with a Christian God, predicated on ideal mental forms: on the other, an account of virtuous human action in the real world, predicated on practical reasoning and the role of pleasure in living a good life. Raphael’s books proclaim the reconciliation or “Concordia” of two opposed strands of Greek thought: ideal and practical wisdom. A similar pairing in the foreground depicts the two main branches of mathematical learning. On the right, Euclid, founding father of geometry and architecture, demonstrates a parallelogram to his enraptured students: on the left, Pythagoras, the first man to call himself a philosopher, teaches the system of musical harmony and numbers at his feet.89

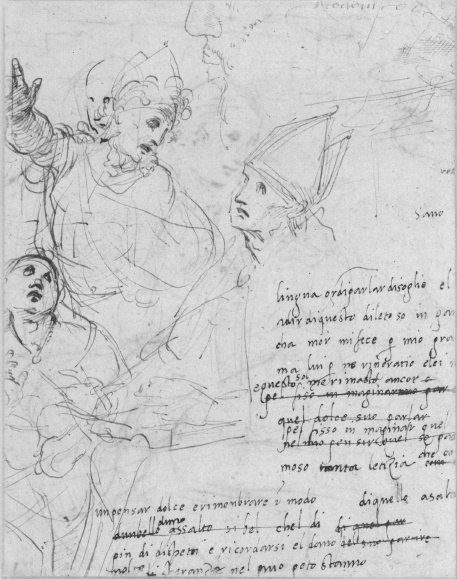

Books serve as supplements to interior dialogue or thought, the unrepresentable activity that challenges visual attempts to depict philosophy.90 Figures of reading and writing in Raphael’s fresco (along with geometry and mathematics) have the same function as the inward-looking man of thought, Il pensieroso. They allude to the field of signs (“the sign, which wants to produce intellection”), rather than to Raphael’s representation of three-dimensional bodies in space.91 The multiplied signs of writing in Raphael’s School of Athens command us to “Read!” But they pose a challenge to reading. Even the most exhaustive scholarly attempts at deciphering Raphael’s “lacunose” fresco have left the gaps and puzzles that bewildered Goethe. We can only make informed guesses about Raphael’s program, which remains at once timeless and historically specific.92 Earlier, I suggested that Michelangelo was penning a love-sonnet, his handwriting displayed for all to see (if not decipher). Here too, we can only speculate. But poetry enters Raphael’s work toward the Stanza della Segnatura in the form of manuscript drafts alongside drawings and studies for La Disputa, on another wall.93 (See figure 2.9.) While his thoughts were on his split-level representation of Christian Theology—bishops, saints, flying angels, Christ, God the Father himself—Raphael was composing tender love-sonnets to his mistress. What are we to make of this? Or rather, did Twombly make something of it?

In the scheme of Renaissance Neoplatonism, exalted secular and erotic love were considered compatible with divine sapientia—a first rung on the ladder to divine Beauty.94 Raphael’s five surviving sonnets (in no way comparable to Michelangelo’s poetic achievement) are addressed to a beloved whose distinguishing quality is the ability to read his arcane meaning. In courtly fashion, Raphael refers to the lover’s ensnaring by the luminous eyes and the snow-and-roses of his beloved’s complexion. Although burning with love, his ardor makes him long to burn even more; being unyoked from her arms is mortal punishment, so he remains silent, lost in thoughts of his beloved: “D’altre cose i’ non dico, che fur molte, / chè soperchia dolcezza a morte mena, / e però taccio, a te i pensier rivolti” (“Of other things [which are many] I do not speak because a surfeit of sweetness leads one to death, and so I am silent, with my thoughts turned to you”).95 The sonnet emphasizes veiled mysteries that are startlingly compared to Pauline love: “Come non potè dire d ‘arcana Dei,’ / Paolo, come disceso fu dal cielo / cosi il mio cuore d’un amoroso velo / ha reciperto tutti i pensier miei” (“Just as Paul could not explain the mystery of God when he came down from heaven, so my heart has covered all my thoughts with a veil of love”).96 His beloved rewards him by recognizing the passion behind his hesitancy: “il foco nascosto / io portai nel mio petto ebbe tal grazia, / che inteso alfin fu il suo spiar dubbioso” (“the hidden fire that I carried in my heart obtained such reward, because in the end its hesitant glimmer was understood”).97 The writer’s paradoxical silence, secrecy, and indirection prove his worth as a lover.

2.9. Raphael, Study for La Disputa (with sonnet fragment), ca. 1508–9. Pen, 7⅝ × 6 in. (19.3 × 15.2 cm). Graphische Sammlung Albertina, Vienna (205v.). © Albertina, Vienna.

Twombly’s multiple Studies for School of Athens during 1960 suggest that he was “studying” Raphael’s fresco with a view to making his own painting.98 The title Studies, however, may allude to something other than Twombly’s own preliminary work toward his School of Athens—in other words, it may play on the titles of Raphael’s drawings, his much-prized (and much-studied) “Studies for …” discrete elements in his frescoes. Raphael’s drawings of bishops, angels, leaning figures, and feet are startlingly juxtaposed with sonnet-drafts enumerating the physical attributes of his beloved: Twombly’s 1960 series of Studies contains proliferating allusions to male and female genitalia, leaping phallic figures like those in his Triumph of Galatea, and quotations from Sappho’s most famous lyric, “Invocation to Aphrodite” (“the bright air / trembling at the heart to the pulse of countless fluttering wing-beats”).99(See figure 2.10.) Along with their exuberant sexuality, floating hearts, and signs drawn from Twombly’s private lexicon (sexual parts, lakes, mountains), they contain ideograms that clearly allude to Raphael’s fresco: numbered flights of steps, carefully drawn outlines of doors with annotated measurements, tondo-like “details.” In all of them, heart-signs (or heart-shaped buttocks)—sometimes surrounded with scribbles of pubic hair or punctuated with anuses—float pinkly across the canvas, as if to bring into view what remains invisible in Raphael’s scene of instruction: the homoerotic subtext of Greek pedagogy (and papal courts).

2.10. Cy Twombly, Study for School of Athens, 1960. Rome. Lead pencil, wax crayon, oil paint on canvas, 40½ × 51¼ in. (103 × 130 cm). Private collection, Italy. © Cy Twombly Foundation. Photo courtesy Gallery Heiner Bastian.

Twombly refers with evident affection to his 1961 School of Athens—“it’s so glowy, the canvas and everything.”100 (See figure 2.11.) This supremely assured painting is among Twombly’s great achievements of the early 1960s. The reduplicated barrel-vaults of Raphael’s School of Athens reappear as arching, dynamic semicircles, lower down in Twombly’s painting than in Raphael’s fresco—indicating a foreshortening of the viewer’s perspective, as well as appreciation of the intricately patterned geometry that structures the fresco’s soaring architectural spaces.101 Dark gold paint accentuates a rectangle in the foreground (unrelated to an actual doorway at the lower left); the blue-gray background suggests sky. Omitting the dynamic groupings of teachers and students, Twombly focuses on the apex of Raphael’s fresco: the airy architecture of recession, with its glimpses of sky and out-of-sight cupola, its whites-on-off-whites and hypothetical vanishing-point.102 The eye is drawn upward by patches of white that suggest what Mallarmé calls “the cloud that floats upon the inward chasm of each thought”—thought rendered as a dialectic of white-outs.103 Scribbles and ideograms (step-outline, mountain range, indecipherable words and phrases) loom faintly beneath layers of white paint. Pink and blue scrawls boost the composition skyward: red and brown fingermarks maintain hands-on contact. A boxed patch of brilliant yellow illuminates the upper right of the canvas, like Plato’s sun of truth or Aristotle’s light without which it is impossible to see.104

Twombly’s first School of Athens is linked to his 1961 Triumph of Galatea and Bay of Naples by the two flesh-pink circles outlined in blue at the upper right margin. These pulsating marks of desire—the artist’s subjective imprint within the painting?—are Twombly’s equivalent to Raphael’s gaze of Agathon: the sign of (less-than-ethereal) masculine desire, or sheer pleasure in paint. Twombly’s approach in his second School of Athens (1964), belonging to the same period as the 1964 Il Parnasso, is architectural, almost academic.105 (See figure 2.12.) The distinguishing shape of Raphael’s barrel-vault with its inscribed title has moved to the top of the painting; lines suggestive of Renaissance perspective emphasize the organization of space in the lower part of Raphael’s fresco (skewed as if seen from the far right). The labeled figures of Plato and Aristotle occupy the focal point. Three horizontal lines run across the width of the lower half of the canvas, corresponding to Raphael’s three-tier design (floor- or eye-level; the flight of steps; the raised area with Plato and Aristotle). Twombly lays bare the perspectival scheme (what Alberti calls “the parallels traced on the pavement”) that underlies Raphael’s figural drama.106 His painting offers an art-historical lesson about the role of Renaissance perspective in painting and philosophy—once a matter of intricately plotted geometrical lines and mathematical calculations, but today largely understood as physical or metaphorical “point of view.”107

For Panofsky, the history of perspective was as much a triumph of objectivity “as an extension of the domain of the self.”108 Twombly’s second School of Athens uses another system: abstraction. A pencil scribble labels the figure of Apollo, above a dripping patch of white. Below and to the left, peach-colored paint and a looping upright (Twombly’s figure-of-eight line of beauty?) single out the graceful figure of Raphael’s Alcibiades listening to Socrates talk. Raphael’s blues, peaches, pinks, and reds become lively painterly activity; blue or green scribbles allude to the clothes worn by Raphael’s figures; peach, rose-pink, and white provoke a rich entanglement of color and line. The painter’s red-dipped fingers are drawn casually across the canvas; a red scrawl recalls the isolated, red-cloaked figure lost in thought at the right of Raphael’s fresco. A knot of thick pink impasto focuses attention in the vicinity of the two artists, Raphael and his painter-friend Sodoma, or else on the lively group next to them—the fresh-faced youths and children clustered around Euclid with his compass. This fleshly love-knot conveys delicious pleasure in the complications of paint meeting paint, with its mingling of hands-on color and swirling heart shapes. Barthes calls color Twombly’s “Joy,” the joy inside him, and “color is also an idea (a sensual idea).”109 Color is a mode of thought.

2.11. Cy Twombly, School of Athens, 1961. Rome. Oil paint, oil-based house paint, wax crayon, lead pencil on canvas, 74⅞ × 78⅞ in. (190.3 × 200.5 cm). Cy Twombly Foundation. © Cy Twombly Foundation. Photo courtesy Gallery Heiner Bastian.

2.12. Cy Twombly, School of Athens, 1964. Rome. Oil paint, wax crayon, lead pencil on canvas, 80¾ × 86¼ in. (205 × 219 cm). Private collection, Cologne. © Cy Twombly Foundation. Photo courtesy Gallery Heiner Bastian.

At the base of Twombly’s School of Athens, festoons corresponding to the trompe l’oeil swags at the foot of Raphael’s fresco restage the drama of thought: not just the performance of consecrated culture, but the painter’s own mode of knowledge-production. In The Origin of Perspective, Damisch asks: “What is thinking in painting, in forms and through means proper to it? And what are the implications of such ‘thinking’ for the history of thought in general?” His answer lies in the relation between the formal apparatus provided by perspective (“equivalent to that of the sentence”) and the ways in which perspective, by assigning the subject a place within a system that gives it meaning, “open[s] up the possibility of something like a statement in painting.”110 For Damisch, meaning only occurs when the subject is situated within a network of signs. We could read the names, punctuation marks, directional pointers, and dramatic foreshortening in Twombly’s School of Athens as a syntax that gestures beyond the discursive realm to the flat plane where painting reflects on itself; and beyond that, to the structures without which no statement can be made in painting.111 This syntax points to the mode of thought that distinguishes painting from poetry and philosophy as a form of knowledge-transmission.112 Twombly’s “versions” of School of Athens recover the invisible fifth wall of Raphael’s Stanza della Segnatura; in Hegel’s words, they offer a way of “knowing philosophically what art is.”113

CODA: STANZA

European poets of the thirteenth century called the essential nucleus of their poetry the stanza, that is, a “capacious dwelling, receptacle,” because it safe-guarded, along with all the formal elements of the canzone, that joi d’amor that these poets entrusted to poetry as its unique object.

—GIORGIO AGAMBEN, Stanzas114

Giorgio Agamben calls attention to the poetic “stanza” as a receptacle for poetry’s phantasmatic object—joi d’amor—as well as a formal element of the canzone. Like the imaginary room in art, the poetic “stanza” safeguards the spaces of enjoyment. Raphael’s work-in-progress (his “studies” for the Vatican frescoes) imply the Renaissance adjacency of Eros and drawing, poetry and philosophy. His frescoes aim to heal Plato’s “ancient quarrel between philosophy and poetry” (a reconciliation for which Plato himself leaves the door ajar in the Republic).115 Agamben makes Plato’s “scission of the word”—“between poetry and philosophy, between the poetic word and the word of thought”—foundational to culture.116 The implications of this split are “that poetry possesses its object without knowing it while philosophy knows its object without possessing it.” The word in Western culture is imagined, on one hand, as “a word that is unaware, as if fallen from the sky, and enjoys the object of knowledge by representing it in a beautiful form,” and on the other, as “a word that … does not enjoy its object because it does not know how to represent it.”117 The confrontation between poetry and philosophy seems irreconcilable. Not to know, but to enjoy? Or to know, while foregoing the pleasures of representation?

The paintings that Twombly sets in dialogue with each other can be viewed in light of this long-running scission: the quarrel expressed by Plato as the fictiveness of painting and poetry in the face of philosophy’s anti-mimetic rigor. Hence, for Agamben, the impossibility of poetic projects directed toward knowledge or philosophical projects directed toward joy. While poetry lacks method, philosophy fails to address representation. Only criticism can negotiate this ancient quarrel by repositioning itself between “the enjoyment of what cannot be possessed and the possession of what cannot be enjoyed,” accepting nonpossession and nonenjoyment as necessary conditions.118 Agamben is concerned with the phantasm of love that haunts poetry’s claims from the medieval period onward to be “the stanza offered to the endless joy (gioi che mai non fina) of erotic experience.”119 Demystifying this phantasm takes place in the critical act: “What is secluded in the stanza of criticism is nothing, but this nothing safeguards unappropriability as its most precious possession.” The topology of joy (gaudium) is approached by way of a dance that leads “into the heart of what it keeps at a distance.”120

Like the “nothing” secluded in Agamben’s stanza, the emptying out that takes place in Twombly’s painting precludes appropriation. The figurative door or window may be open or closed, the space of painting flat or overlaid with a perspectival grid. Either way, Twombly resolves Plato’s argument between mimetic painter-poet and truth-telling philosopher, foregrounding painting’s constitutive container—its stanza or room, the canvas that Barthes calls the “Rare Rectangle” (in Italian, il quadro).121 The wisdom of art eloquently evoked by Barthes, the transient enjoyment finely parsed by Fisher—the scriptible and syntactical dimensions of aesthetic pleasure—consists in the performance of signs, enjoyed in the spatio-temporal confines of painting. Combining psychogram (the artist’s signature) and Parnassus (poetic tradition), Twombly’s paintings generate the trope of reading because the pleasurable dance of signs defines painting’s specific action. In this disciplinary domain, the ends of enjoyment are inseparable from those of knowledge.