2

THE BUSINESSMAN,

THE ACTRESS &

THE DISMEMBERED

MISTRESS

Henry Wainwright, 1875

And, long since then, of bloody men,

Whose deeds tradition saves;

Of lonely folks cut off unseen,

And hid in sudden graves;

Of horrid stabs, in groves forlorn,

And murders done in caves.

And how the sprites of injured men

Shriek upward from the sod.

Ay, how the ghostly hand will point

To show the burial clod:

And unknown facts of guilty acts

Are seen in dreams from God!

From The Dream of Eugene Aram by Thomas Hood (1799–1845)

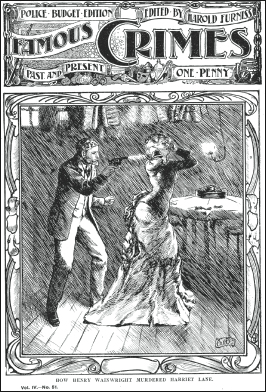

The East End of London is a place of many contrasts, perhaps none greater and more visible than the juxtaposition between rich and poor; the wealthy on Whitechapel Road living cheek-by-jowl with some of the poorest and most marginal people in the land. Henry Wainwright was one of the fortunate ones. He had grown up in an affluent family where his father, a respectable tradesman, was a pillar of society in business and public life and a church warden of the parish. When he died he left the handsome sum of £11,000 to be divided between his four sons and one daughter. Henry and his brother Thomas went into partnership running a brush-making business with a shop at No. 84 Whitechapel Road and a warehouse almost opposite at No. 215; they had contracts to supply the workhouse and even the Metropolitan Police. To all outward appearances Wainwright was a typical Victorian gentleman and lived with his wife and children in the smart Georgian Tredegar Square in the Mile End district of the London Borough of Tower Hamlets. Indeed, it was said of Wainwright that, ‘At the beginning of the year 1874 there was probably no more popular or respected individual among the principal inhabitants of that long and broad thoroughfare, the Whitechapel Road, than Mr Henry Wainwright.’ So wrote Henry Brodribb Irving in his introduction to Trial of the Wainwrights in the respected Notable British Trials series (1920). As ever, Irving summed the man up impeccably; to the society around him Wainwright was known for his generous bonhomie, his prominent work with the Christchurch Institute at St George’s-in-the-East, charity work, recitations at educational establishments, ardent support for the Conservative party, patronage of the theatre and social suppers. Indeed, he had a reputation for lavish entertaining, and for actors on very humble salaries it was a much-desired privilege to be asked out to supper with Mr Wainwright. The East-End tragedian J.B. Howe wrote of a chance encounter with Wainwright in his book A Cosmopolitan Actor; after being recognised by Wainwright, Howe was invited to his house, met his family and shared a drink, some entertaining stories and even a cab. As they jumped into the vehicle, Howe noted the affection with which Wainwright bade farewell to his family, kissing the children and his wife. Howe was to recall, ‘I thought I had never in my life encountered a nicer man.’ In the light of subsequent events it was somewhat ironic that Wainwright’s own favourite recitation after social suppers was Hood’s Dream of Eugene Aram (a notorious eighteenth-century case of deception and violent robbery which resulted in murder and the hiding of the corpse): those who saw the performances of this poem recalled Wainwright performing it ‘with force and vigour but without that peculiar sense of horror which makes its recitation so vivid in the hands of a great actor.’ Perhaps their opinions were far more perceptive than the audience realised: in fact, it was not his acting ability which lacked, but rather his own deep-seated callousness that revealed itself through his performance.

Wainwright was often to be found at the Pavilion Theatre, which was next to his shop at No. 84 Whitechapel Road. He was there on the night Arthur Orton, ‘The Tichborne Claimant’, came to raise funds for his approaching trial (a campaign Orton undertook between the years 1873–4 to finance a legal case which gained national notoriety as the longest trial in English legal history, in which Orton attempted to maintain his claim on the Tichborne family name and fortune. In fact, he was a butcher from Wagga-Wagga who was impersonating the lost son of Lady Tichborne). The account tells how, after Orton had finished his oration, the heavy drop curtain was lowered unexpectedly. Unaware of the danger, Orton, who was immediately under the drop, could have been seriously injured had not a man from the audience leapt to his feet and pulled him out of danger. This dramatic act of gallantry was met with thunderous applause and the ‘claimant’ and his rescuer appeared in front of the curtain – hand-in-hand – to receive the audience’s appreciation. The hero that saved Orton was none other than Henry Wainwright.

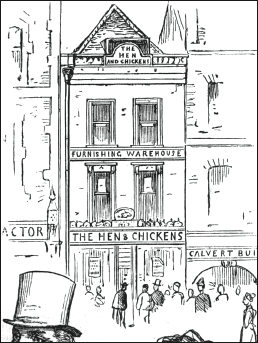

Wainwright’s warehouse at No. 215 Whitechapel Road.

But Henry Wainwright was not all he seemed. He lived a double life. He was, by the standards of the 1870s, where our story really begins, an attractive man of average height, broad shouldered in build, who sported a fine head of dark brown wavy hair, full and penetrating blue eyes and a cultivated beard behind which was concealed ‘a heavy and sensual mouth’ blessed with wit and fine conversation. Among women he was considered to have a certain air of exoticism and no little mystery such as might be attached to an aesthete; all gifts he used to full effect as he charmed and conquered a string of attractive young ladies – or at least that is what he would have liked those to whom he told his tales to believe.

One young lady to fall for Henry Wainwright’s charms was Harriet Lane, whom he met at Broxbourne Gardens, a popular pleasure resort for Londoners at that time on the banks of the River Lea. They soon became intimate and announced their marriage as the union between Percy King (the almost laughable phallic pseudonym of Wainwright) and Harriet Lane in February 1872, and thus the beguiled girl in her early twenties became Mrs Harriet King went to live with her ‘husband’ in a comfortable house on St Peter’s Street, Mile End. In the August of 1872, a daughter was born to them, and after a few moves to Alfred Place, Bedford Square and Cecil Street, Strand, Mrs King returned again to St Peter’s Street, where a second daughter was born in December 1873.

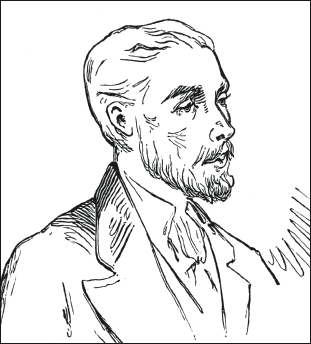

Pillar of society: Henry Wainwright c. 1875.

Harriet Lane, or rather, ‘Mrs Percy King’ – Wainwright’s secret wife.

And so the double life of Henry Wainwright might well have carried on, perhaps ad infinitum, if his extravagances and bonhomie had not taken such a toll on his finances.

Early in 1874 it had become apparent that Henry Wainwright had stretched himself too far and he was facing a financial crisis. He owed his brother William a large sum of money – he could see the danger and dissolved the partnership. Wainwright took on a new partner, but his debts continued to spiral and amounted to well over £3,000 (excluding the money he owed his brother). His creditors met and agreed to accept Wainwright’s offer to repay them 12s in the pound. He never paid more than 9s.

Wainwright was thus unable to support his secret second family in the style to which they had become accustomed. Harriet had been given an allowance of £5 a week and was quite happy – she proclaimed she was ‘kept like a lady’ – but now, little by little, the allowance diminished and she was forced to consider herself, quite rightly, as being of ‘reduced circumstances’. She had to give up the St Peter’s Street house and take up lodgings at the house of a Mrs Foster at 3 Sidney Square, Mile End Road.

Wainwright’s two worlds began to collide when Harriet, frustrated by her lack of financial support, took to visiting Wainwright’s shop at 84 Whitechapel Road and making ‘unpleasant scenes’. Wainwright could see his upright and respected façade about to be destroyed by Harriet’s outbursts, and the whole sordid situation exposed for all society to gossip and dissect. His vanity and pride, made all the more sensitive through his pecuniary situation, could not allow this to happen. On one occasion Wainwright was seen to become violent with Harriet. He had tired of her and despised her for her loyalty to him. She would not be palmed off to another man, Wainwright had no money to pay her off, and rather than have his clandestine activities exposed and face being ostracised by his family and society he decided to rid himself of Harriet once and for all.

On 10 September 1874 Wainwright ordered half a hundredweight of chloride of lime which was delivered to 84 Whitechapel Road. The following day Harriet King left her lodgings at 4 p.m., taking with her a nightdress done up in a small parcel. She told her friend Miss Wilmore she was off to see Wainwright at his shop on Whitechapel Road.

On that same evening of Friday 11 September 1874 three workmen employed near Wainwright’s warehouse at 215 Whitechapel Road claimed they heard three pistol shots fired in quick succession between 5 p.m. and 6 p.m. At the time they did nothing more about what they heard. The lime disappeared and Harriet Lane, ‘Mrs King’, was never seen alive again.

Later, Miss Wilmore became concerned about Harriet and went to see Wainwright. He explained she had run off to live on the continent with a man named Edward Frieake. Soon Miss Wilmore received a letter, purporting to come from Harriet (in reality written by Wainwright’s brother Thomas), in which she said she wanted nothing more to do with Mr King, her family or friends. Further telegrams purporting to come from Harriet were also received. Harriet’s friends were not entirely convinced and sought out Edward Frieake, who turned out to be an auctioneer and friend of Wainwright. He knew nothing of Harriet Lane or a Mrs King. When Wainwright was challenged about this he claimed the Edward Frieake who had run off with Harriet was a different man who simply shared the same name. Did her friends believe this remarkable coincidence? If concerns had been passed to the police they certainly were not acted upon in any significant way. Perhaps the memory of Harriet would have gradually faded to the occasional comment of, ‘I wonder whatever happened to…’ from those who once knew her.

Whatever was generally thought to have happened to Harriet, Henry Wainwright was a changed man. Gone was the hale-fellow-well-met, the bon vivant. Frank Tyars, who had performed at the Pavilion, noticed the change in Wainwright: ‘Instead of the breezy, self-confident gentleman he had known, he saw a man walking slowly along in a furtive, hang-dog way.’ J.B. Howe could not believe the change in his old acquaintance and noted Wainwright ‘had become nervous, impatient and irritable. He had taken to visiting public houses, where he would sit drinking more than was good for him, and nervously cracking and eating walnuts, of which he was very fond.’ Most believed that Wainwright’s personality change was a result of his financial embarrassment, but surely the weight of the murder must have hung heavily and most horribly on his conscience.

By September 1874 Wainwright’s business was near collapse and he was obliged to raise money by mortgaging the warehouse at 215 Whitechapel Road. In June 1875 Wainwright was declared bankrupt and in the July the mortgagee of 215 foreclosed and took possession of the premises. But Wainwright was not without friends, and he was lucky enough to count Mr Martin, a well-to-do corn merchant at 78 New Road, Whitechapel, among them. He acquired Wainwright’s business, advanced him £300 and even paid Wainwright a salary of £3 a week as manager. But the thought of Harriet still haunted Wainwright – which was hardly surprising considering he had buried her with the quick lime under the floor of the paint room in the warehouse. Some had, over the months since her disappearance, commented on the foul smell at the warehouse, but, because Wainwright had kept his double life so secret, nobody put two and two together.

Perhaps it was because the fateful anniversary of Harriet’s murder was approaching, or perhaps because his nerve could simply hold on no more, either way Wainwright wanted her remains out of the warehouse. However, he was in for a shock when he discovered what was left of poor Harriet. No doubt he was expecting the lime to have reacted with her remains and hastened their destruction. This would have been the case if Wainwright had bought quicklime (otherwise known as caustic lime, or unslaked lime), however, the chloride of lime Wainwright had bought had worked as a disinfectant and preserved the body!

Despite the split with the business partnership, Henry co-opted his brother, Thomas, to allow him to remove the body to his ironmongery shop premises at the Hen and Chickens at 56 Borough High Street. This arrangement is curious: why should Thomas Wainwright feel compelled to assist his brother hide a murder? And having just had his own business fail, if Harriet’s body was hidden in his cellar, how long would it be before they had to remove it again? Whatever the motives (loyalty? Bribery?), on Friday 10 September the brothers bought a quantity of American cloth, some rope, an axe and a spade. The following morning, a year to the day after Harriet had left her lodgings for the last time, a friend of Thomas Wainwright recalled ‘he did not look well’ – hardly surprising if one considers the work he assisted his brother with the previous night: Harriet had been dismembered and parcelled up in the American cloth.

A dramatic representation of Henry Wainwright shooting Harriet Lane on the cover of Famous Crimes, c. 1910.

Thomas had gone on ahead to his premises; it was thus left to Henry to organise the transportation of the body. Wainwright went to Mr Martin’s, where he saw one of the managers, Alfred Stokes. Wainwright undoubtedly trusted Stokes as he had also been in his employ in the brush-making business for about eighteen years. At Wainwright’s trial he was to give the following account of the afternoon in question:

…about half-past four, when, in Mr Martin’s presence he (Wainwright) asked, ‘Will you carry a parcel for me, Stokes?’ I said, ‘Yes sir, with the greatest of pleasure.’ We then went together to 215 Whitechapel Road, in through Vine Court to the back premises. Henry took a key out of his pocket and opened the door. We both went in, and he told me to go upstairs and fetch down a parcel. I went upstairs, and through by the skylight… but did not find the parcel. I came downstairs and told him I could not find it; he said, ‘Never mind, Stokes, I will find them where I placed them a fortnight ago, under the straw.’ I saw some straw up in a corner, and two parcels wrapped in black American cloth, and tied up with rope. He said, ‘These are the parcels I want you to carry, Stokes.’ I lifted them up and I says, ‘They are too heavy for me,’ and put them down. [Wainwright persuaded Stokes to try again.] I picked up both parcels and followed him. I then said ‘I can’t carry them; they stink so bad, and the weight of them is too heavy for me.’

Plan of Whitechapel Road showing the premises at No. 84 and No. 215, occupied by Henry Wainwright.

Wainwright took the lightest of the parcels from Stokes and they managed to get almost as far as Whitechapel Church, where Stokes begged to rest and appeared to lose his grip a little. Wainwright snapped, ‘For God’s sake don’t drop it, or else you will break it.’ When they arrived at the church Wainwright told Stokes to wait with the parcels while he went for a cab. In going for the cab personally, rather than sending Stokes, Wainwright sealed his own fate. While he was gone, Stokes looked in the parcel. Much was made of Stokes’ motive for doing so in the press, for the man claimed he had heard ‘a supernatural voice which had called to him three times saying, “Open that parcel.”’ The judge anticipated this aspect of Stokes’ testimony and cut across him, saying, ‘Never mind what you felt you must do. You were asked what you did.’

Alfred Stokes – the man who dared to look in one of the ominous parcels.

Stokes stated, ‘I looked into the largest parcel. I opened the top of the parcel, and the first thing I saw was a human head. Then proceeding further I saw a hand, which had been cut off at the wrist.’

Stokes closed the parcel and kept his cool as Wainwright brought over a four-wheeled cab. Wainwright lit a cigar while Stokes loaded the parcels and watched the cab set off. He then set off in pursuit, running along behind. At a chemist shop near Greenfield Street, about 70 yards from Church Lane, the cab stopped and Wainwright got out and caught up with a young lady named Alice Day, a ballet dancer he knew from the Pavilion Theatre. She had just come out of a pub on the corner of Greenfield Street and Wainwright asked her if she cared to have a drive over London Bridge. She accepted, so long as she could get back for her evening performance. Puffing on his cigar to mask the foul smell, Wainwright, Alice and parcels set off in the cab – with Stokes in pursuit, vainly trying to attract the attention of two policemen along the way.

The cab reached the Hen and Chickens in Borough High Street, where Wainwright got out before the cab had really stopped. He carried one of the parcels inside. Meanwhile, Stokes had managed to attract the attention of a police officer, PC Henry Turner M48, who came over to the cab and waited for Wainwright to return and walked with him as he carried a second parcel from the cab into the Hen and Chickens. PC Turner asked Wainwright, ‘Do you live here?’ To which Wainwright replied, ‘No.’ Turner pressed further, ‘Do you have any business here?’ Clearly agitated, Wainwright retorted, ‘I have and you have not.’ Turner told Wainwright to ‘go inside’, but he seemed disinclined to do so. Another constable, PC Cox M290, joined Turner. The policemen lost patience and pushed Wainwright inside.

Thomas Wainwright’s premises at the Hen and Chickens, 56 Borough High Street.

Wainwright was now left with little option but bribery and begged: ‘Say nothing, ask no question and there is £50 each for you.’ Cox replied, ‘No, we are going to do our duty, and we don’t want your money.’ By this time Turner had his hands on Wainwright and walked with him down the premises; Wainwright still had the second parcel in his left hand. Cox found one of the parcels Wainwright had brought in lodged in a dark corner at the top of the cellar steps. PC Turner asked Cox to hold Wainwright while he retrieved the parcel and put it on an old counter. Wainwright warned, ‘Don’t open it, policeman: pray don’t look at it; whatever you do don’t touch it.’ The stench was vile, but investigate he did, by pulling some of the cloth to one side – and in doing so, Turner recalled, ‘my fingers then came right across the scalp of a head, across the ear’. Returning Wainwright to the hands of Turner, Cox went to get the cab; Wainwright was desperate and pleaded with the policmen, ‘I’ll give you £100, I’ll give you £200, and produce the money in twenty minutes if you’ll let me go.’ PC Turner remained unmoved; Wainwright and Miss Day were arrested and taken to Stone’s End police station.

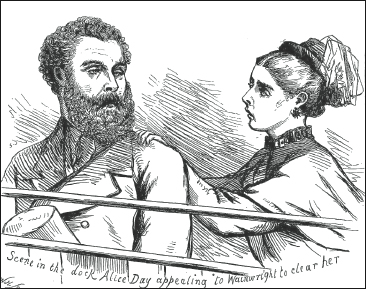

On 13 September Henry Wainwright (36) and Alice Day (20) were charged at Southwark Police Court. Depositions were given by Stokes and the constables involved in the arrest. Wainwright remained silent throughout the proceedings until Miss Day clutched hold of him and implored him, ‘For God’s sake tell them what I know of the matter – I know nothing.’ Wainwright responded, ‘I met her Saturday. She knows nothing.’ Both were remanded in custody and brought before the Police Court on 21 September. Alice Day was discharged early on, Wainwright was formally charged with wilful murder. Thomas Wainwright was arrested on 1 October, charged at Southwark Police Court with being an accessory after the fact, and on 13 October both brothers were committed for trial. On 14 October the final judgement of the coroner’s jury confirmed the remains were those of Harriet Lane, alias King, and that she was wilfully murdered by Henry Wainwright.

The Illustrated Police News’ sensational depiction of the discovery of the dismembered remains of Harriet Lane.

An interesting aside to the proceedings at the Police Court is that Mr Besley, who led the defence for the prisoner, shared the instruction with none other than Mr W.S. Gilbert, who later collaborated with Arthur Sullivan to create the Savoy operas. Gilbert had qualified as a barrister but had given up his practice to concentrate on writing. He had found himself called for jury service at a most inopportune time and discovered to his consternation that only practicing barristers were exempted – thus he made this fugitive appearance and claimed his exemption.

The trial of the Wainwright brothers at the Central Criminal Court opened on 22 November before Sir Alexander Cockburn, Lord Chief Justice of England. Sir John ‘Sleepy Jack’ Holker, the Attorney General, led the prosecution with Mr Harry Poland. The defence for Henry Wainwright was led by Mr Edward Besley with Mr Douglas Strait and Mr C.F. Gill. Counsel for Thomas Wainwright was conducted by Mr Moody.

In the dock at Southwark Police Court, Alice Day implores Henry Wainwright to clear her name.

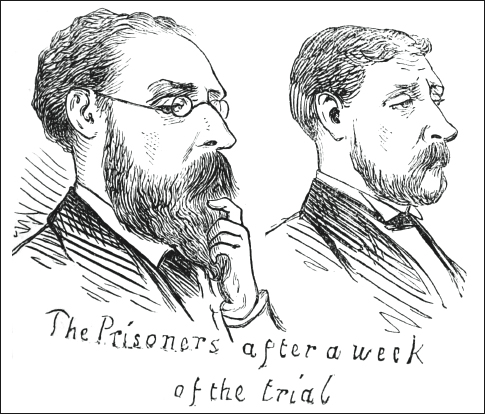

Sketched from life, Henry (left) and Thomas Wainwright after a week of their trial at the Central Criminal Court.

Despite the Chief Justice, in his opening remarks, speaking of ‘the magnitude and importance of this great trial’, the truth was that despite the circumstances of murder being both sensational and remarkable, the case was not – the evidence was so clear and unequivocal, the proof of his guilt overwhelming, but still the most senior counsel laboured their speeches, the Attorney General devoting a whole day to his closing speech and the Chief Justice another day for his summing up. The entire trial stretched over nine long days.

The trial finally concluded on 1 December. The jury retired to consider their verdict at 3.45 p.m. After an absence of nearly an hour the jury returned a unanimous verdict of ‘guilty’ against Henry Wainwright. Thomas Wainwright was found guilty of being an accessory after the fact and sentenced to seven years penal servitude. Many who studied the case were to recall Thomas had a near miss: had it not been for the eloquence of his defence he would have undoubtedly faced the same fate as his brother.

Before sentence was passed, Henry Wainwright was asked if he had anything to say. He attempted to enter into a speech but was brought to the point by the Lord Chief Justice. Wainwright acquiesced, saying:

Then I will imply say that, standing as I now do upon the brink of eternity, and in the presence of that God before whom I shall shortly appear, I swear that I am not the murderer of the remains found in my possession. I swear also that I have not buried these remains, and that I did not exhume or mutilate them as proved before you by witnesses. I have been guilty of great immorality. I have been guilty of many indiscretions, but as for the crime of which I have been brought in guilty I leave this dock with a calm and quiet conscience.

Once sentences were passed on the brothers and they were taken down, the Lord Chief Justice exercised the power vested in him to order a reward, the sum of £30, to be granted to Stokes ‘for his conduct and energy… and his perseverance in following up the cab in which those remains were being conveyed [that] in reality led to the discovery of this crime and the conviction of the offender concerned in it.’

Petitions were made for the sentence to be commuted and attempts were made to publicly discredit a witness. The Times of Tuesday 21 December reported ‘a rumour’ that a document written by Henry Wainwright was in the possession of the Home Secretary, the contents of which related:

That being in pecuniary embarrassment, he grew weary of the importunities of Harriet Lane and the constant drain upon his purse. Harriet Lane had threatened that unless he gave her more money she would expose him to the world as the father of her children, which to a man in his social position meant ruin and degradation. He mentioned these circumstances to his brother Thomas who said he was confident that for a consideration of £20 some man could be got to marry her and take her away.

‘He donned the black cap’ – Sir Alexander Cockburn, Lord Chief Justice of England, pronounces the death sentence on Henry Wainwright.

‘Wake up Wainwright – you have an appointment to keep!’ Henry Wainwright in the condemned cell at Newgate, just hours before his execution.

Wainwright went on to claim he paid his brother the money, but Thomas ‘went to Henry at 84 Whitechapel Road and said he had got rid of her, and on being asked how, replied that he had shot her.’ Henry exclaimed, ‘Good God, Tom, what have you done?’ He threatened to inform the police, to which Thomas replied if he did so, ‘he would swear Henry did it.’ She was Henry’s paramour and she was laying on his premises, so, in the days before forensics or use of fingerprints in detection, what chance would he have had? So he complied. Thomas was also said to have made a similar statement – except this time it was he who was forced by Henry, the killer, to comply for fear of implication.

On Tuesday 21 December 1875 Henry Wainwright was executed at Newgate Prison by public executioner William Marwood. Wainwright was led out across the yard to the execution shed as the nearby clock of St Sepulchre chimed 8 a.m. Wainwright had clearly dressed with ‘scrupulous care’, his bearing as he walked demonstrating ‘conspicuous fortitude.’ A friend of H.B. Irving was present and described the scene to him as:

absolutely Hogarthian and horrible… the cold December morning, the waning moon, the rope dangling to and fro in the shed awaiting its victim, a gaslight flaring noisily, the well-dressed crowd of privileged visitors (about sixty in number) come to see the show, the Sheriff’s footmen, who had some of them obviously fortified their spirits for the occasion; the whole scene seemed ghastly and sickening in the last degree.

Wainwright had been given a special dispensation to smoke a last cigar, which he discarded as he approached the gallows. Looking over his shoulder with a glance of infinite scorn, and then, with a contemptuous movement of his head, he called to those assembled to witness the execution, ‘Come to see a man die, have you, you curs!’ Speaking no more Wainwright went to his doom with this curse upon his lips. Another who was present noted:

After the white cap had been drawn over his face and while the noose was being adjusted, the heaving of deep emotion was distinctly visible through the folds of the cap. The necessary preparations were speedily made by the executioner, and all things being in readiness, the drop fell with an awful shock echoing for a moment or two all over the prison yard… Judging from the tension of the rope for some considerable interval after the bolt had been drawn the prisoner must have ‘died hard’, as the saying goes.