The Prospector

It is ten thirty-six am when Ruth pulls into a parking space opposite the bathrooms at the Ballarat Visitor Information Centre and I run for the disabled stall because it is the one closest to the car. Ruth calls them the Welcome Toilets because of their proximity to the replica of the Welcome Nugget mounted at the front of the centre. It is a quirky name, but I can see the sense of it. At the very least, she is a logical person.

The Ballarat Visitor Information Centre proclaims that Ballarat is the ‘Birthplace of the Australian Spirit’. This is why we have decided to come. To see for ourselves. To commemorate our trip, I elect to have my photograph taken standing beneath the replica nugget. The Welcome Nugget was found on Bakery Hill, Ballarat, in 1858. It is the second-largest nugget discovered in Australia. It is flanked on either side by details of the region’s richest gold discoveries: Canadian 1 – 1117 ounces; Lady Hothay – 1177 ounces; Sarah Sands – 1619 ounces. The Welcome Nugget weighed in at 2217 ounces.

I smile for the picture. Happy Brad.

In another shot I put out my arm and pretend to support the nugget on my upturned hand.

The next stop on our tour is the Eureka Diorama. The Eureka Diorama is in the Eureka Stockade Memorial Park on Eureka Street, just up the road from the Eureka Stockade Centre, which houses an exhibition space and the Archimedes Cafe.

It costs eight dollars to enter the Eureka Stockade Centre, to ‘relive the battle ... on the very site of the battle,’ whereas it costs only twenty cents to visit the Eureka Diorama, to bring the Eureka Diorama to life.

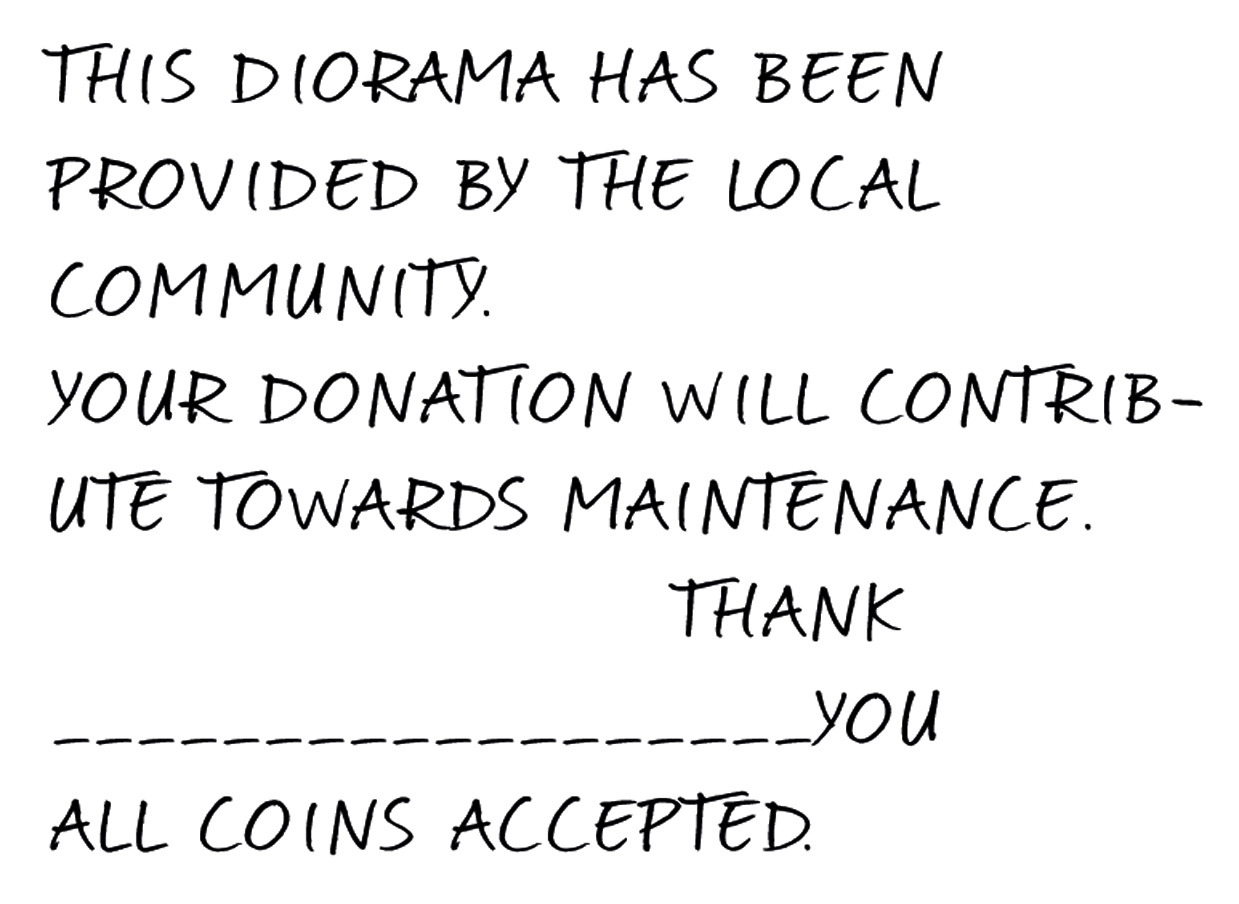

A handwritten note above the coin slot advises:

Compared to eight dollars, twenty cents seems like a small price to pay.

The lights come on. The story begins. A man’s voice punctures the silence. It reverberates loudly in the small space. The sound attracts nearby picnickers and sightseers.

‘We swear by the Southern Cross to stand truly by each other and fight to defend our rights and liberties...’

The recording crackles with enthusiasm.

We stand around like a bored school group, waiting for the experience to end. The guy next to me is getting pushy. It pisses me off, his need for elbow space, particularly as I was the one who paid the twenty cents. I refuse to move. You’re an arsehole, I think, standing my ground.

It occurs to me that the symbolism of the Eureka Stockade makes it an excellent backdrop for a relationship break-up. There is the battle theme, with its bloodshed, fuelled by injustice and oppression. There is the momentous nature of the Incident. There is the whole saga of broken promises, betrayal, and misplaced trust. And besides, I like the theatre of it. Life imitating history, imitating life.

This is one of the reasons why Ruth’s friend and flatmate, Kimberley, calls me a bastard. Because of my appreciation of context.

She is a girl who calls a spade a spade. I would sleep with her precisely for this reason, and this reason alone. Despite her poor dress sense. If she would just say yes.

I decide to tell Ruth towards the end of the day, after we have finished most of our touring around. I haven’t thought exactly how I am going to put it, but the words seem to come to me as we are viewing the King flag at the Ballarat Fine Art Gallery. I will talk about ‘autonomy’ and ‘freedom’ and my willingness to fight to defend it. I will talk about being governed by the truth versus being governed by the rule of law; about when it is right to obey the law and when to obey it is to betray what you know to be true. I will talk about the beauty of poetry and memory and the symbolism of the Southern Cross. I will make reference to the dignity of the human spirit, and something about caged birds.

Needless to say, I am inspired by the history of the town, by the self-conscious construction of its significance. Ballarat is the tale of the Eureka Rebellion. Here, there is no other story.

I imagine myself afterwards commiserating with Peter Lalor over a whisky in the local pub. To extend the fantasy, I suggest to Ruth we have a drink at the Eureka Stockade Hotel. ‘They also have Foxtel,’ I add, but Ruth isn’t interested. ‘Let’s just go for a walk in the gardens,’ she says.

I envisage a short, volatile scene, followed by tears, and an awkward drive home. There is some potential for break-up sex once we reach her apartment, although it is partly dependent on the whereabouts of Kimberley. I don’t invest too much in this outcome. I prefer not to get my hopes up.

We had intended to stay overnight at the Welcome Stranger Holiday Park, but that is not going to happen now, of course. I chose the place largely because of its name, but also because it offered pinball machines, table tennis and a free electric barbecue. The advertisement said it was Affordable in a Big Way, the enthusiasm of which appealed to me. I was also drawn in by the promise that it would be A holiday you will remember.

This much, at least, it seems will be realised.

Prime Ministers Avenue traverses the length of the Ballarat Botanical Gardens on a north-south axis. Technically, it is an avenue within an avenue, located inside the precinct of Horse Chestnut Avenue. Established in the 1860s, the gardens were planted on the site of the old Ballarat Police Horse Paddock. This choice of location says everything about Ballarat citizenry and their long, troubled relationship with authority.

The avenue is necessarily a work in progress; so far it sports twenty-five bronze prime ministers’ heads. Something about the way the busts peer out at me makes me want to push them off their pedestals.

We are standing before Gough Whitlam when Ruth begins to speak. I am lost in contemplation of the ridge just beneath his nose when something about the tone of her voice advises me to pay attention. ‘It is not,’ she says, ‘anything specific.’ In fact, this is one of the reasons why she wants to end it. ‘Because it is all so vague,’ she says. ‘It isn’t going anywhere.’ Also, she thinks I am interested in other women. Like the way I look at Kimberley. Mostly, though, she just thinks I am too intense.

‘What do you mean, intense?’ I ask, irritated by the breadth of the description. ‘How can I be unfocused and intense at the same time?’

‘It’s things like that,’ she says. ‘The way you ask that question.’

My glare could bore a hole right through her skull.

‘I just don’t want to do it anymore,’ she continues. ‘I’ve thought about it a lot lately, and, well, I’m sorry.’

Whitlam’s shadow has cast me in darkness. I don’t really know what to say.

Opposite the Ballarat Botanical Gardens on Wendouree Parade is Lake Wendouree, site of the 1956 Olympic Games rowing, kayaking and canoeing events. The name comes from the local Aboriginal word ‘wendaaree’, and means to ‘go away’. I had intended to have our talk there. After our historic tram ride, when Ruth had seen everything she wanted to see. It would have been the logical spot to wrap this up. A sentimental yet picturesque end to our journey. The site of bittersweet memory, but with an irony I am sure she would have come to appreciate in time.

Instead, she has beaten me to it. A full length ahead. And so unexpected.

It dawns on me that I may have underestimated her. Not only in pulling off a move like this, but without remorse. She is positively un-guilt-stricken. She is neither apologetic, nor feigning sadness. She is simply businesslike and direct – she expresses regret for making us break the holiday-park reservation; she offers to reimburse me.

As we approach the car I suggest it is not too late to change our minds. The reservation still stands. The holiday park is only five minutes away.

‘We could be there in no time,’ I say playfully, cocking my head.

Ruth doesn’t acknowledge that I’ve spoken. She just turns the key in the lock then gets into the car.

Ballarat’s Avenue of Honour is the longest such avenue in Australia. Stretching twenty-two kilometres along the Ballarat Burrumbeet Road (an extension of the Old Western Highway), it was originally planted with 3771 trees – one for each soldier from the Ballarat region who enlisted in the war during the period from June 1917 to August 1919.

As we pass through the Arch of Victory I begin to count them. One after another after another. There is no time to read their brass plates. At first I try, but they quickly blur as we pick up speed.

There is something distinctly egalitarian about this commemoration, where soldiers are lauded for their service without regard to their military rank. There is something distinctly Australian about it, this ecumenical commemoration of spirit.

Ruth’s sights are set directly on the road in front of her. Hard above the wheel, no room for deviation.

At this rate we should be home in almost an hour.

Before too long I lose count of the trees. Beside me, Ruth remains silent, concentrating on the traffic. I consider getting out my book to read, but I know reading will only make me feel sick. Instead, I prop my feet up on the dash and focus on the view. The atmosphere inside the car is still. I wind down the window, turning my chin to the sky, and feel the breeze rush against my face. It smells of the countryside, sodden and sharp. I take a deep breath, then settle back in my seat. From a bird’s-eye view I imagine Ballarat receding fast behind us. As we continue forward beneath the sunset, my gaze levels out at the middle distance.