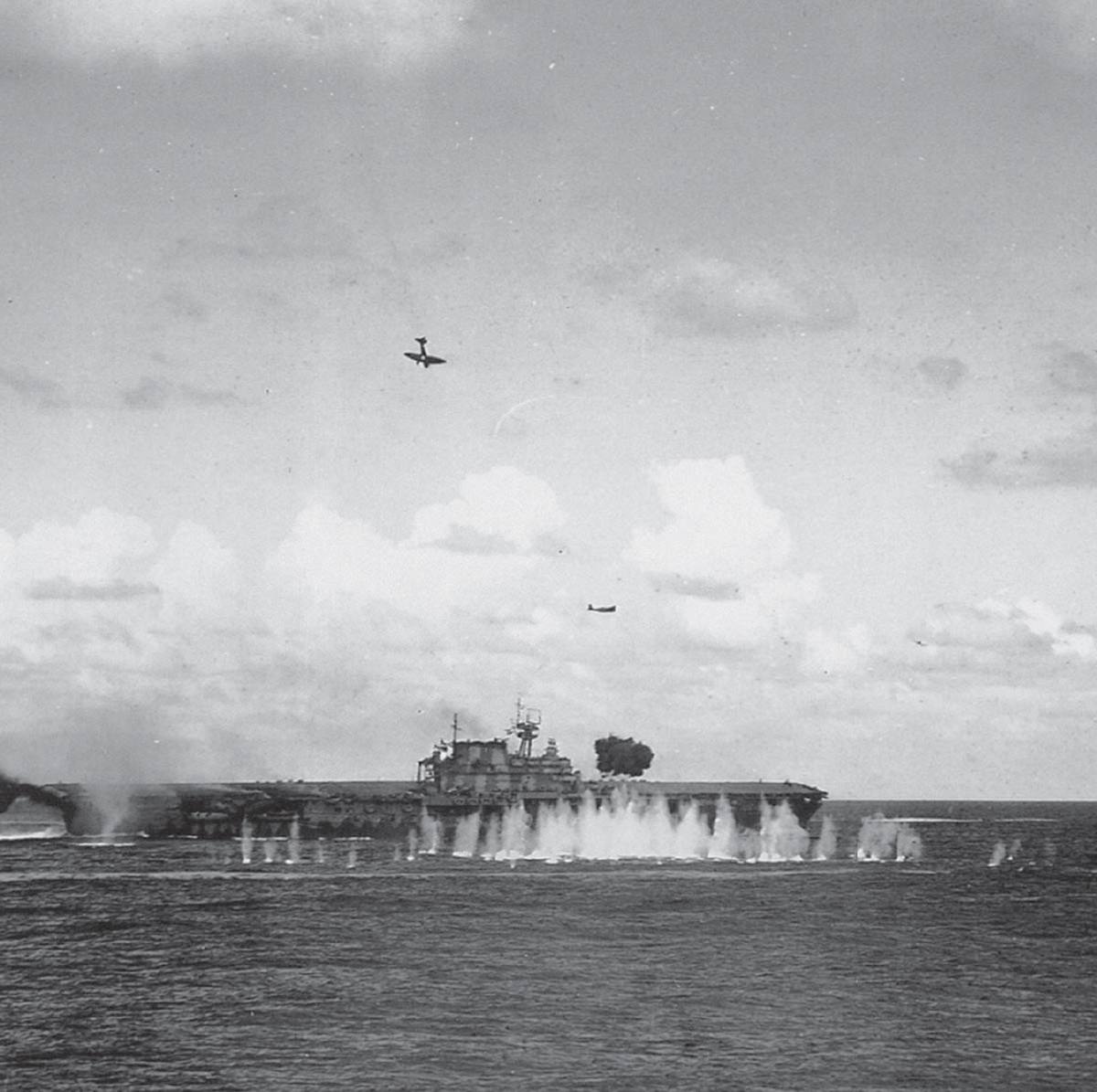

The Japanese carrier force gave its best performance of the war during the Battle of Santa Cruz on October 26, 1942. In this view, a well-coordinated strike of Japanese dive- and torpedo bombers cripples the carrier Hornet, which later sank. (Naval History and Heritage Command)

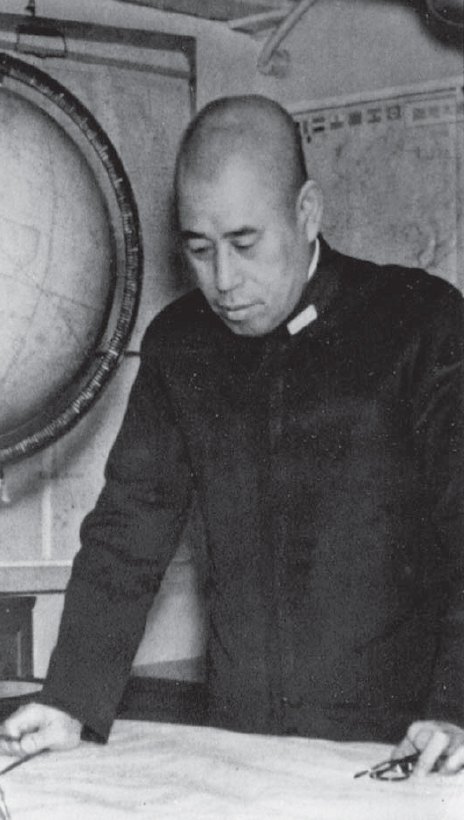

The primary operational entity of the IJN was the Combined Fleet. Virtually all combat elements of the IJN were under its control except forces operating off China and local defense forces of key bases. At the start of the Pacific War, the Combined Fleet allocated significant forces to the Pearl Harbor operation. This included the Kido Butai with its six fleet carriers; escorting the carriers were two Kongo-class battleships and the two new Tone-class heavy cruisers, supported by one light cruiser and nine destroyers. The IJN’s primary objective during the initial phases of the conflict was to seize the lightly defended oil resources in the Dutch East Indies and British possessions in the Far East, which offered Japan a way to escape the effects of the Allied trade embargo. To accomplish this, the Second Fleet (with the majority of the IJN’s heavy cruisers) and Third Fleet were sent to the southern areas, supported by powerful land-based air units. The First Fleet, with seven battleships after the commissioning of Yamato in December 1941, remained in Japan as a strategic reserve. These were being held back for the anticipated decisive battle. The Fourth Fleet based at Truk defended the Central Pacific and was tasked to seize several Allied-held islands. The Fifth Fleet was tasked to defend Northern Japan. Most of the IJN’s modern submarines were assigned to the Sixth Fleet based in Kwajalein in the Marshall Islands, and most of these were allocated to support the Hawaiian operation.

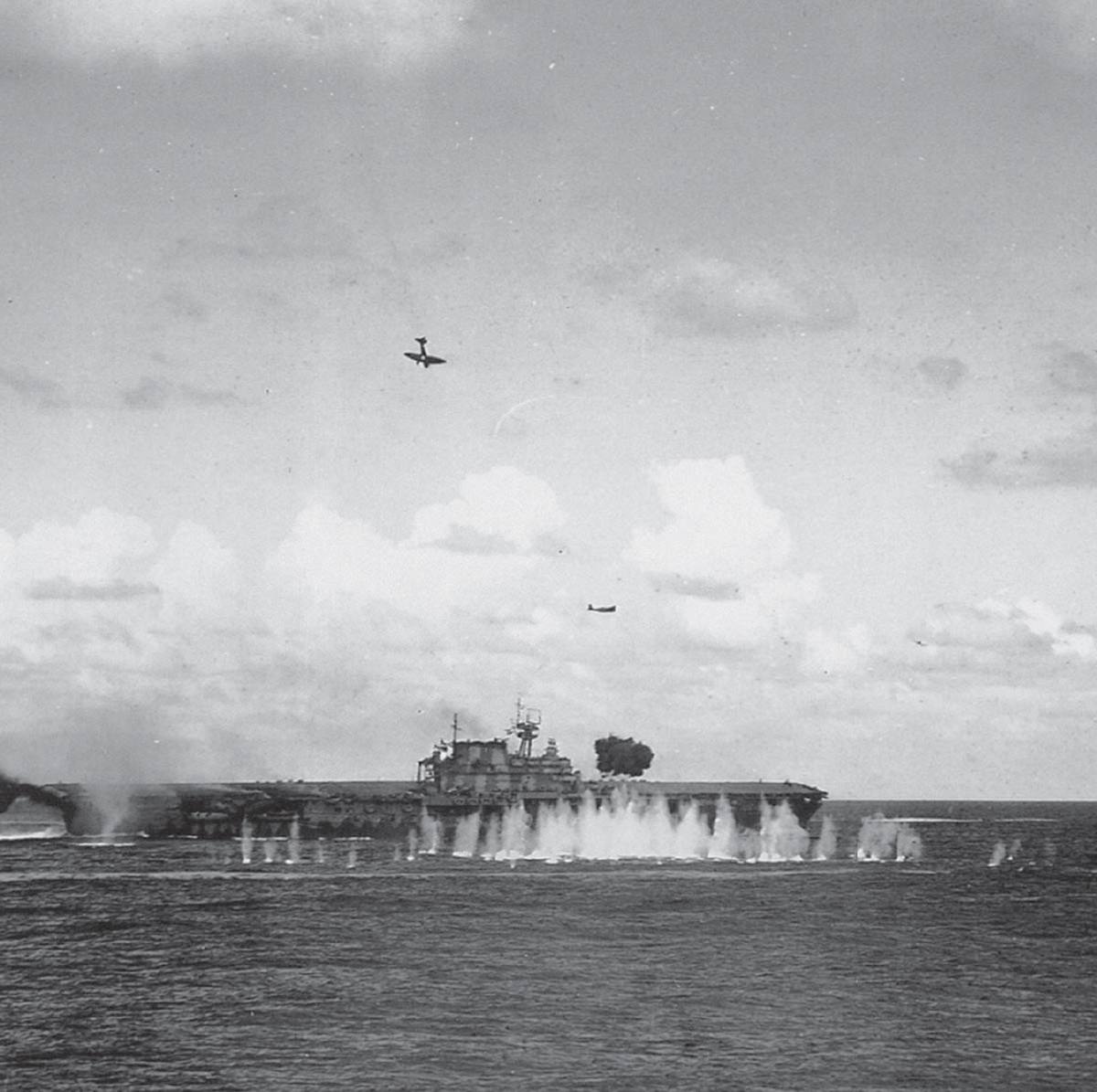

The driving force behind the Pearl Harbor attack was the commander of the Combined Fleet, Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto. Against almost universal skepticism he achieved his goal of opening the war against the United States with a daring attack against the heart of American naval power. (Naval History and Heritage Command)

This wartime force allocation reflected a very different strategy from the one for which the IJN had been planning and training for the past 30 years. This was due to the views and actions of a single man – Isoroku Yamamoto, who assumed command of the Combined Fleet in August 1939. Yamamoto changed the IJN’s passive wartime strategy to a much more aggressive forward strategy almost overnight. According to his chief of staff, Yamamoto first discussed an attack on Pearl Harbor in March or April 1940. After the completion of the Combined Fleet’s annual maneuvers in the fall of 1940, Yamamoto directed that a Pearl Harbor attack study be performed under the utmost secrecy. By December, Yamamoto had decided to conduct the Pearl Harbor operation. Not only was this a risky operation which exposed the IJN’s most powerful striking force to early destruction, but it obviously changed Japan’s strategic calculus by bringing the US into the war. A war which could have been fought for the limited goal of seizing Dutch and British possessions in the East Indies and Malaya was instantly transformed into a total war against the most powerful nation on Earth. Yamamoto’s decision was fateful for the IJN and Japan since it condemned both to a prolonged and bitter war that neither was capable of conducting nor even fully understood.

It is impossible to understate the impact of the Pearl Harbor attack for the IJN. Yamamoto was convinced that war with the United States was inevitable once the Japanese began hostilities. He believed that, since a traditional victory against the US was not possible, he had to shatter American morale and force a negotiated peace. For this reason, he scrapped the IJN’s traditional passive strategy of creating a decisive battle in the western Pacific in favor of an initial blow so crippling that it would undermine American morale. What happened was actually the reverse. The attack so enraged the Americans that any hope of a negotiated peace was removed. With the benefit of hindsight, there is little doubt that had Yamamoto kept to the IJN’s basic strategy of defending against an American drive across the Pacific, the IJN would have been much better off. Yamamoto sold the attack to the Naval General Staff on the basis that it would provide the time required to complete the conquest of the East Indies. In fact, since the Combined Fleet held a numerical advantage over the USN’s Pacific Fleet in every category, and since the Japanese-held islands in the Central Pacific provided a barrier, the Pacific Fleet did not have the military or, even more importantly, the logistical means to interfere with the Japanese attack south. In the final analysis, the Pearl Harbor raid was militarily unnecessary.

Yamamoto had great difficulty getting his risky plan to attack Pearl Harbor approved by a skeptical Naval General Staff. Among other things, the Naval General Staff was responsible for directing operations and exercised supreme command over the IJN. This is not how Yamamoto viewed the situation. In a series of meetings on October 17–18, 1941, Yamamoto threatened to resign unless his plan was approved. This threat brought final approval, since Yamamoto was viewed as too valuable to lose. This was not the last time that Yamamoto would use this tactic.

Making the whole scheme possible was the Kido Butai with its six carriers with over 400 embarked aircraft. In Yamamoto’s mind, the purpose of the raid was to sink American battleships since this, he believed, would shatter American morale. In fact, Yamamoto was expecting to lose at least a third of the Kido Butai in the operation, meaning that he was content to trade his modern carriers for outdated American battleships. The staff of the Kido Butai saw things differently and planned to use the weight of its attack aircraft against any American carriers present.

The results of the attack of December 7, 1941 are well known, but the impact of the attack is less well understood. The two waves of 350 aircraft gained complete surprise and successfully hit their intended targets. The attacks against airfields were very successful and crippled any possibility of the Americans mounting an effective airborne defense or launching a retaliatory strike on the Japanese carriers.

With total surprise gained, the well-trained Japanese aircrews dealt a series of heavy blows against the Pacific Fleet. The 40 torpedo bombers were the most important part of the plan since they were targeted against the American battleships and carriers. Of the eight battleships present, five were exposed to torpedo attack. Japanese torpedo aircraft accounted for battleships Oklahoma and West Virginia sunk, two torpedoes into battleship California which eventually sank, and a single hit on Nevada which started a chain of events that led to its sinking. In addition, torpedoes damaged two light cruisers, and sank a target ship and a minelayer. All this cost only five torpedo bombers.

The efforts of the torpedo bombers were complemented by 49 level bombers armed with 1,760lb armor-piercing bombs. Dropping from 10,000ft, the Japanese scored ten hits. One of these penetrated the forward magazine of battleship Arizona and completely destroyed the ship. The other hits slightly damaged battleships Maryland, West Virginia, and Tennessee.

The 167 aircraft of the second wave accomplished much less. This part of the attack included 78 dive-bombers with the IJN’s best crews. However, against stationary targets, they scored only some 15 hits including five on battleship Nevada as it slowly moved down the channel to the harbor entrance. The battleship was beached to avoid blocking the channel. A single bomb hit was scored against battleship Pennsylvania located in dry dock but caused only light damage. Light cruiser Honolulu suffered a near miss that caused moderate damage.

American losses were heavy, but were ultimately insignificant when placed in the context of subsequent naval production. The IJN sank or damaged 18 ships. Of most importance to Yamamoto, five battleships were sunk or beached. All but two (Arizona and Oklahoma) returned to service; one (Nevada) returned in 1943 and the other two (West Virginia and California) returned in 1944. The three other battleships damaged in the attack were all back in service by February 1942.

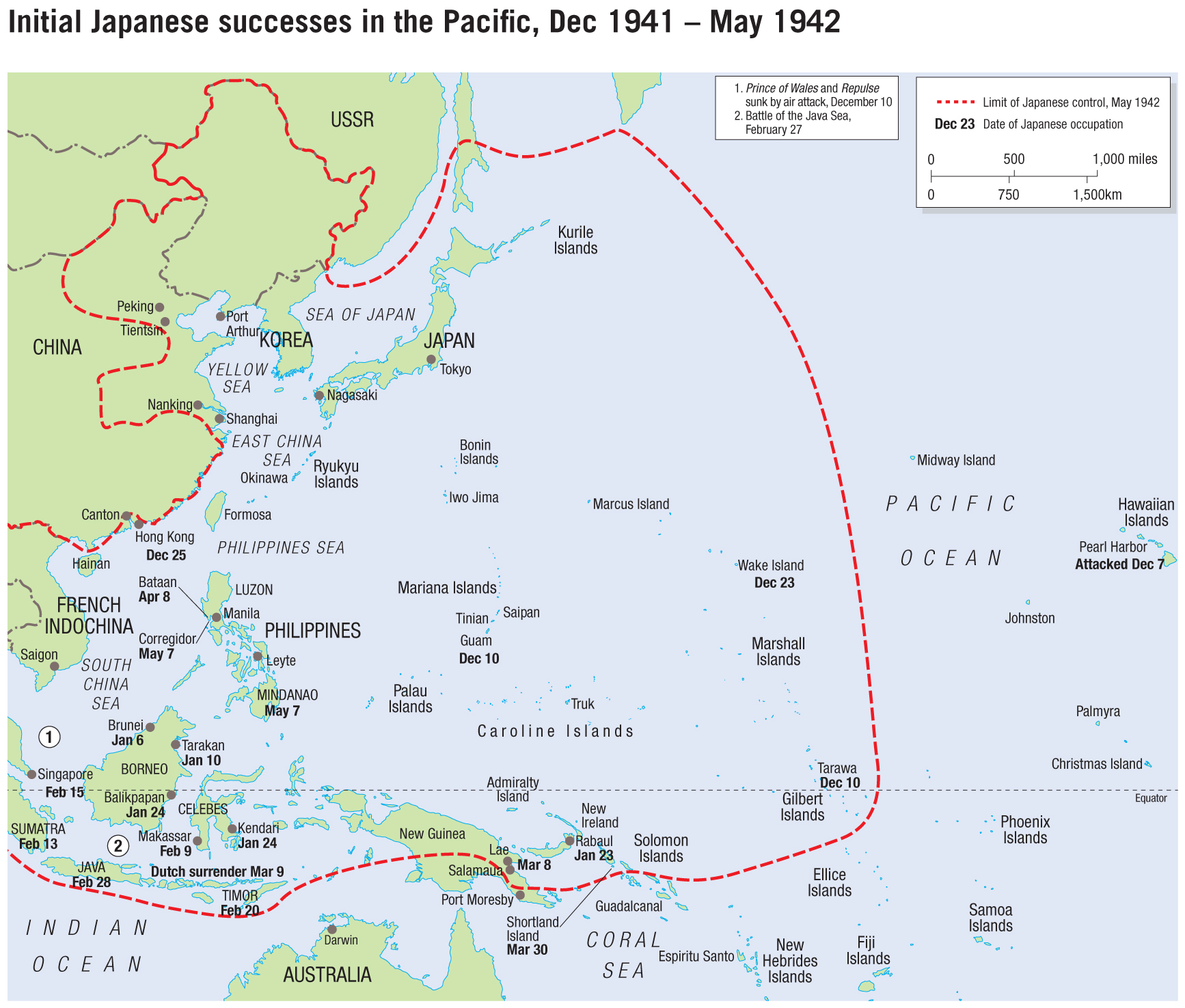

The IJN thought that it was fighting a limited war in which it would seize key objectives and then use the power of the defense to defeat American counterattacks, which in turn would lead to a negotiated peace. The initial period of the war was divided into two “operational phases.” The First Operational Phase was further divided into three separate parts. During these, the major objectives of the Philippines, British Malaya, Borneo, Burma, Rabaul and the Dutch East Indies would be occupied. The Second Operational Phase called for further expansion into the South Pacific by seizing eastern New Guinea, New Britain, the Fijis, Samoa, and “strategic points in the Australian area.” In the Central Pacific, Midway was targeted as were the Aleutian Islands in the North Pacific. Seizure of these key areas would provide defensive depth and deny the Allies staging areas from which to mount a counteroffensive.

Much to the surprise of the IJN, the First Operational Phase went according to plan with extremely light losses – no ship larger than a destroyer was sunk. The invasion of Malaya and the Philippines began in December 1941 and a notable success was scored on December 10 when Japanese land-based long-range bombers operating from bases in Indochina sank British capital ships Prince of Wales and Repulse in the South China Sea.

The American island of Guam was seized on December 8 after token resistance. The British Gilbert Islands were seized on December 9 and 10. The only temporary setback was the failure of the first attempt to seize Wake Island on December 11. In response to this failure, a carrier division from the Pearl Harbor attack force was added to the forces allocated for the second attempt, which was mounted, this time successfully, on December 22. The bastion of British power in the Far East, the fortress of Singapore, surrendered on February 15.

Allied naval opposition to the IJN during the First Operational Phase was sporadic and ineffective. In the first major surface engagement of the war on February 27 at the Battle of the Java Sea, an Allied cruiser-destroyer force was defeated by a Japanese force of similar size. Following its debut at Pearl Harbor, the Kido Butai supported the capture of Rabaul in January 1942 and the Dutch East Indies in February. The only problem during the First Operational Phase was the failure to occupy the Philippines on schedule. However, with no prospects of reinforcement, the fall of the Philippines was only a matter of time and the last American and Filipino forces surrendered in early May 1942.

The last major operation of the First Operational Phase was the Combined Fleet’s raid into the Indian Ocean. This large operation included five carriers of the Kido Butai to neutralize the RN’s Eastern Fleet and a task force built around heavy cruisers to attack shipping in the Bay of Bengal. The operation began in April with the Kido Butai delivering heavy attacks against RN bases at Colombo and Trincomalee. The Japanese also caught and sank a British light carrier and two heavy cruisers at sea, but were unable to locate and destroy the main British fleet. The Japanese cruiser raiding force wreaked havoc with British shipping in the Bay of Bengal. The entire operation was a strategic dead end since it was only a temporary projection of power that could not be sustained, and only served to put more strain on the Kido Butai.

This poor-quality photo from a Japanese wartime magazine shows the British carrier Hermes under attack by Japanese dive-bombers. The carrier was sunk on April 9, 1942, as it withdrew south following the Japanese attack on Trincomalee on Ceylon. (Courtesy of Michael A. Oren)

The ease with which the IJN accomplished its First Operational Phase objectives created a phenomenon called “Victory Disease.” This led to the IJN’s severe underestimation of the enemy and the resulting failure to concentrate the IJN’s superior forces at key places and times. As a result, the critical months of May and June 1942 saw the IJN lose both its offensive power and the initiative. The Second Operational Phase was planned to expand Japan’s strategic depth by adding eastern New Guinea, New Britain, the Aleutians, Midway, the Fijis, Samoa, and “strategic points in the Australian area.” However, the Naval General Staff, the Combined Fleet, and the Imperial Army, which had to contribute troops for some operations, all had different views on the sequence of operations.

The Naval General Staff advocated an advance to the south to seize parts of Australia. The Imperial Army declined to contribute the forces necessary for such an operation, which quickly killed the concept. The Naval General Staff still wanted to cut the sea links between Australia and the United States by capturing New Caledonia, Fiji, and Samoa. Since this required far fewer troops, on March 13 the Naval General Staff and the Imperial Army agreed to operations with the goal of capturing Fiji and Samoa.

The Second Operational Phase began well when Lae and Salamaua on eastern New Guinea were captured on March 8. However, this was to be the last of the uninterrupted victories for the IJN. On March 10, American carrier aircraft struck the invasion forces and inflicted considerable losses. This raid had major operational implications since it forced the Japanese to stop their advance in the South Pacific until the Combined Fleet provided the means to protect future operations from USN carrier attack.

Yamamoto had an entirely different strategy in mind. In his view, it was essential to complete the destruction of the USN, which had begun at Pearl Harbor. He proposed to do this by attacking an objective that the Americans would be certain to fight for. His choice was Midway Atoll since it was close enough to Hawaii that he assessed the USN would be forced to contest a Japanese invasion there.

The Shokaku at Coral Sea under attack by American carrier aircraft. The carrier was struck by three bombs and could not be repaired in time for the Midway operation. Its sister ship, the Zuikaku, was also unable to participate in the Midway operation after its air group suffered crippling losses. This removed one third of Yamamoto’s heavy carriers from his would-be decisive battle. (Naval History and Heritage Command)

In a series of meetings from April 2–5 between the Naval General Staff and representatives of the Combined Fleet, a compromise was reached. Yamamoto got his Midway operation, but only after he again threatened to resign. However, in return, Yamamoto had to agree to two demands from the Naval General Staff both of which had potential implications for the Midway operation. To cover the offensive in the South Pacific, Yamamoto agreed to allocate one carrier division from the Kido Butai to the early May invasion of Port Moresby on New Guinea. Yamamoto also agreed to include an attack to seize selected points in the Aleutian Islands concurrent with the Midway operation. These were enough to remove the IJN’s margin of superiority in the coming Midway attack.

The attack on Port Moresby, codenamed the MO Operation, was divided into several phases. In the first phase, Tulagi would be occupied on May 3. Then the carriers borrowed from the Kido Butai would conduct a wide sweep through the Coral Sea to find and attack Allied naval forces. The landings on Port Moresby were scheduled for May 10.

As was typical in IJN operational planning, the MO plan was overly complex and depended on close coordination of widely separated forces. Another hallmark of the plan and of IJN planning in general was the almost complete disregard for the actions of the enemy. By committing only a portion of the Kido Butai, Yamamoto not only jeopardized the success of the MO Operation, but also imperiled Yamamoto’s decisive Midway operation if those ships were lost or damaged.

The MO Operation featured a force of 60 ships led by carriers Shokaku and Zuikaku, one light carrier (Shoho), six heavy cruisers, three light cruisers, and 15 destroyers. Additionally, some 250 aircraft were assigned to the operation including 140 aboard the three carriers.

The actual battle did not go according to the IJN’s tightly scripted plan. Tulagi was seized on May 3, but the following day aircraft from the American carrier Yorktown struck the invasion force. For the next two days, both the American and Japanese carrier forces tried unsuccessfully to find each other. On May 7, both carrier forces went into action, and both achieved disappointing results. The Japanese carriers launched a full strike on a contact reported to be carriers. The report turned out to be false, and the strike force found and struck only an oiler and a destroyer. The American carriers also launched a major strike on incomplete reconnaissance. Instead of finding the main Japanese carrier force, the Americans were forced to settle for an attack against Shoho, which was quickly sunk. This was the largest Japanese ship lost so far in the war.

Finally, on May 8, the opposing carrier forces found each other and exchanged strikes. The 69 aircraft from the two Japanese carriers succeeded in sinking carrier Lexington and damaging Yorktown. In return, the Americans damaged Shokaku, but left Zuikaku undamaged. However, aircraft losses to Zuikaku were heavy, and the Japanese were unable to support a landing on Port Moresby. As a result, the MO Operation was canceled.

The battle was a disaster for the IJN. Not only was the attack on Port Moresby stopped, which constituted the first strategic Japanese setback of the war, but all three carriers committed to the battle would now be unavailable for the Midway operation. In fact, after the Pearl Harbor attack the six carriers of the Kido Butai never again acted together as a single group. Had this force been kept together, it would have been very difficult for the USN to handle.

Yamamoto saw the Midway operation as the potentially decisive battle of the Pacific War which could open the door for a negotiated peace favorable to Japan. Unfortunately for the IJN, the Combined Fleet’s plan for the MI Operation (as the attack on Midway was codenamed) was flawed. It took the Japanese penchant for complexity and using far-flung forces to a new height, and, most importantly, it ignored the actions of the enemy.

For this operation, the Kido Butai had only four carriers. Assuming strategic and tactical surprise, these would knock out Midway’s air strength and soften the atoll for a landing by 5,000 troops. Following the quick capture of the island (which was another faulty assumption (this time untested) as the combat elements of the landing force were not much larger than the well entrenched American defenders), the Combined Fleet would lay the foundation for the most important part of the operation. Midway was nothing more than bait for the USN which would dutifully depart Pearl Harbor to counterattack after Midway had been captured. When the Pacific Fleet arrived, Yamamoto would concentrate his scattered forces to crush the Americans.

An important aspect of Yamamoto’s decisive battle scheme was Operation AL, the plan to seize two islands in the Aleutians concurrent with the attack on Midway. Despite persistent myth, the Aleutian operation was not a diversion to draw American forces from Midway. Yamamoto wanted the Americans to be drawn to Midway, not away from it. The forces directly engaged in this operation constituted a considerable drain on the IJN’s resources. These included two carriers, six cruisers, and 12 destroyers. Distant cover for Operation AL was provided by another four battleships, two light cruisers, and 12 destroyers. The positioning of these forces made them useless in the upcoming battle.

The ultimate result was that the Japanese were actually outnumbered at the point of contact where the battle would be decided. An American force of 26 ships faced the 20 ships of the Kido Butai with an aircraft count of 233 (348 if Midway is included) against the Kido Butai’s 248.

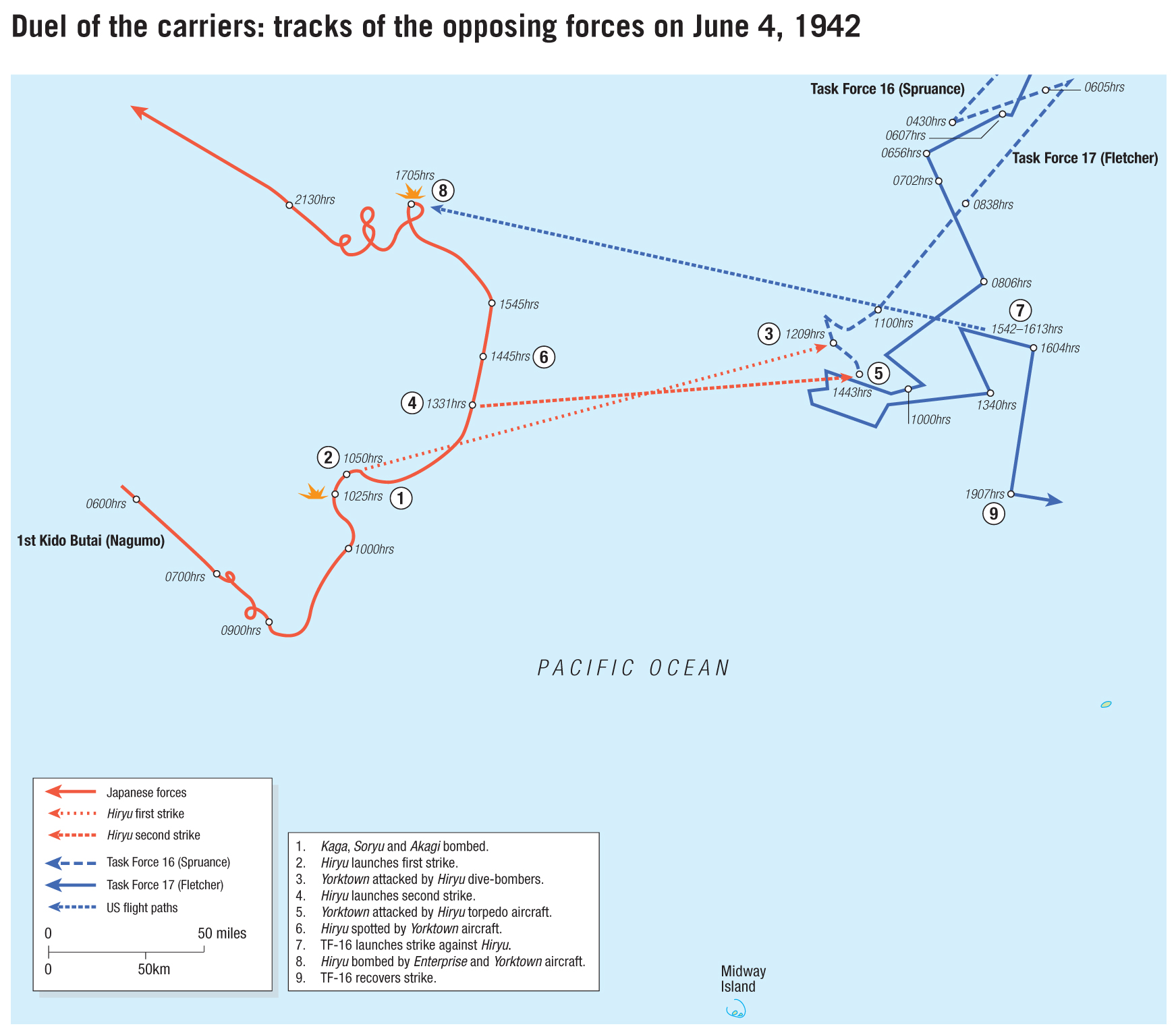

The battle opened on June 3 when American aircraft from Midway spotted and attacked the Japanese transport group 700 miles west of Midway. At 0430hrs on June 4, the Kido Butai launched a 108-aircraft strike on the island. The attackers brushed aside Midway’s defending fighters at about 0620hrs, but failed to deliver a decisive blow to the island’s facilities. Most importantly, the strike aircraft based on Midway had already departed to attack the Japanese carriers, which had been spotted at 0530hrs. This information was passed to the three American carriers, and soon 116 carrier aircraft, in addition to the aircraft from Midway, were on their way to attack the Kido Butai.

A view of Hiryu taken by one of Hosho’s Type 96 carrier attack aircraft on the morning of June 5. Based on this sighting, a destroyer was ordered to the scene, but Hiryu finally sank before it arrived. (Naval History and Heritage Command)

The aircraft from Midway attacked bravely, but they failed to score a single hit on the Kido Butai. In the middle of these uncoordinated attacks, a Japanese scout aircraft reported the presence of an American task force. Unfortunately for the Japanese, it was not until 0830hrs that the presence of an American carrier was confirmed. This put the Japanese commander, the timid Vice Admiral Chuichi Nagumo, in a difficult tactical bind in which he had to counter continual American air attacks and prepare to recover his Midway strike, while deciding whether to mount an immediate strike on the American carrier or wait to prepare a proper attack. After quick deliberation, he opted for a delayed but better-prepared attack on the American task force after recovering his Midway strike and properly arming aircraft.

This plan was flawed since the American carrier dive-bombers were already in the air. Beginning at 1022hrs, these surprised and successfully attacked three of the Japanese carriers. With their hangar decks strewn with fully fueled and armed aircraft, all three were turned into blazing wrecks. A single carrier, Hiryu, remained and it launched an immediate counterattack. Both of its attacks hit Yorktown and put the carrier out of action. Later in the afternoon, the two remaining American carriers found and destroyed Hiryu. The striking power of the Kido Butai had been destroyed and the battle lost. Early on the morning of June 5, the IJN canceled the Midway operation. Yamamoto’s decisive battle had in fact turned the tables on the IJN and, with the blunting of Japan’s offensive power, the initiative in the Pacific was up for grabs.

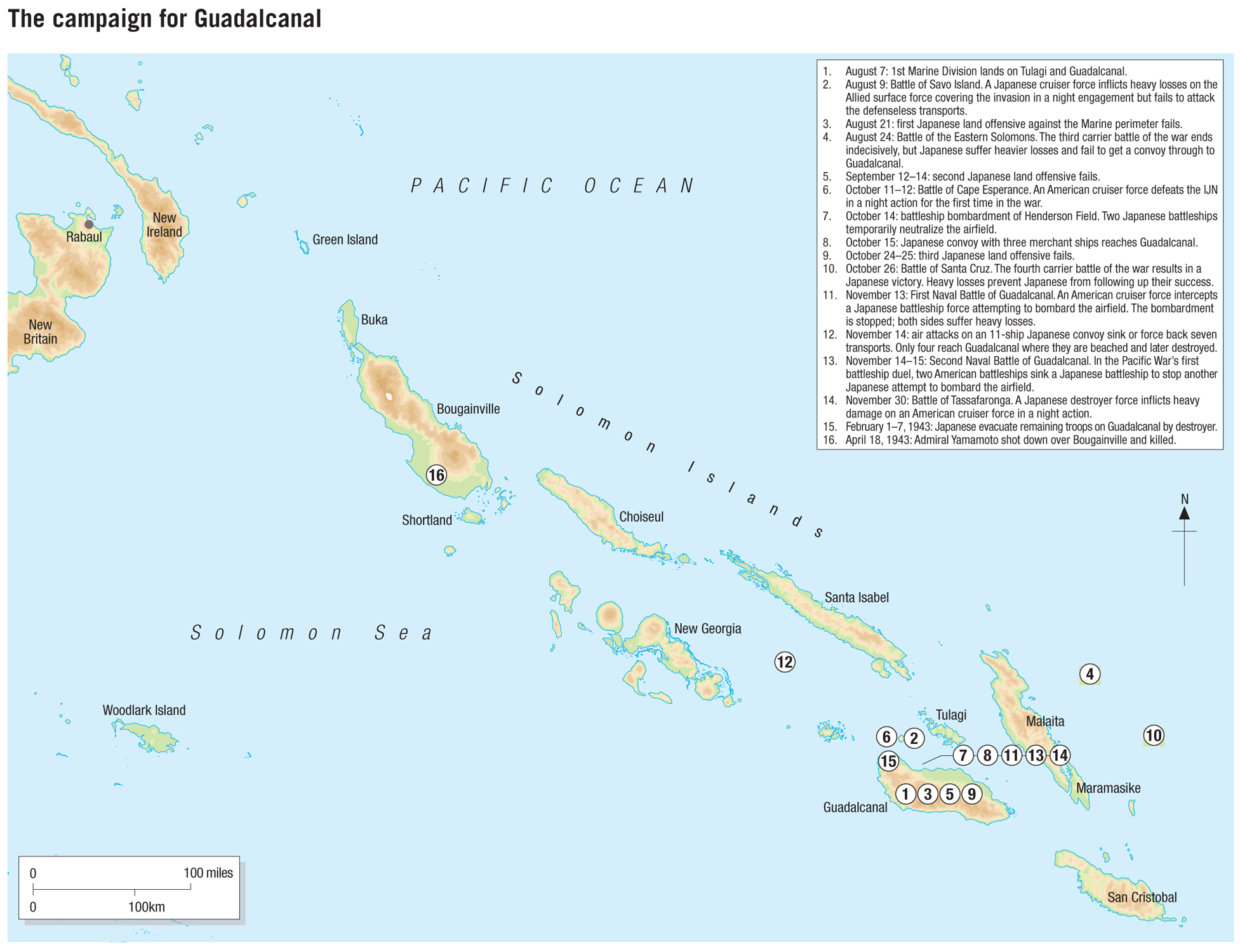

On August 7, the US Navy landed on the islands of Guadalcanal and Tulagi in the Solomons. Now the IJN was on the defensive for the first time.

The local Japanese naval commander, Vice Admiral Gun’ichi Mikawa, commander of the new Eighth Fleet at Rabaul, reacted quickly. He gathered five heavy cruisers, two light cruisers, and a destroyer, and ordered an attack on the Allied invasion force for the night of August 8–9. Mikawa’s bold response resulted in a brilliant victory during which four Allied heavy cruisers (three American and one Australian) were sunk. No Japanese ships were lost. It was one of the worst American naval defeats of the war, only mitigated by the failure of Mikawa to attack the defenseless transports. Had he done so, the first American counterattack in the Pacific could have been stopped dead in its tracks.

The Japanese originally deemed the American landings as nothing more than a “reconnaissance in force.” A fatal pattern of piecemeal commitment by the Japanese now began.

The IJN was slow to respond to the first USN offensive of the war. By the middle of August, it had assembled a force of four battleships, five carriers, 16 cruisers, and 30 destroyers to dislodge the Americans. On August 24–25, the IJN launched an operation to move a small transport convoy to Guadalcanal and to crush any American naval units in the area. The ensuing clash, known as the Battle of the Eastern Solomons, included the third carrier battle of the war. The IJN achieved neither of its goals – the American carrier force was not destroyed and the reinforcement convoy failed to reach the island. Japanese losses were heavy with 75 carrier aircraft lost, a light carrier, a transport, and a destroyer sunk. In return, carrier Enterprise was damaged, but managed to elude Japanese attempts to complete its destruction. With the American-held airfield on Guadalcanal now operational, convoys of slow transports could not be run to the island. Until the airfield was suppressed, Japanese reinforcements could only be delivered by inefficient nightly destroyer runs to the island.

The Japanese continued to underestimate the number of US Marines on the island. By the time some 6,200 Imperial Army personnel had been delivered by destroyer for an attack on the Marine perimeter, Japanese estimates were that only 2,000 marines were on the island. With the number closer to 20,000, the attack launched on two successive nights from September 12–14 failed. Meanwhile, the struggle for control of the waters around Guadalcanal was going better for the Japanese. A Japanese submarine sank carrier Wasp on September 15. This left a single American carrier, Hornet, active in the Pacific. During the same period, the Japanese possessed up to six operational carriers, but the IJN failed to recognize or grasp this opportunity.

By October, it was obvious even to the Japanese that the Guadalcanal campaign was becoming a major test between the IJN and the USN. But the battle could only be won if the Japanese garrison on the island was dramatically reinforced. For the next attack, an entire Japanese division would be employed. Efforts were intensified to get the required force to Guadalcanal by October 13 or 14 so that the offensive could be launched by October 20. To do this, the Combined Fleet promised to step up night runs by destroyers and high-speed seaplane carriers (carrying heavy equipment) to Guadalcanal, to increase air bombardment of the airfield, and to run a large convoy of transports directly to the island. The IJN also decided to use battleships to suppress the airfield allowing the convoy to arrive safely. Yamamoto now defined the Combined Fleet’s primary mission as supporting the recapture of the island; the destruction of the Pacific Fleet was reduced to secondary importance.

On the night of October 13–14, two battleships bombarded the airfield on Guadalcanal with 918 14in rounds, destroying 40 aircraft and putting the airfield temporarily out of commission. Despite all the IJN’s prewar preparations for a titanic clash of battleships, this was the most successful of any Japanese battleship operation during the war.

The Japanese convoy arrived on Guadalcanal on the night of October 14–15, preceeded by two heavy cruisers again shelling the airfield. Aircraft from two carriers flew air cover over the transports. American aircraft did succeed in sinking three of the six transports, but not until 4,500 men had been landed along with two-thirds of their supplies and equipment. The IJN kept up the pressure with another cruiser bombardment on the night of October 15–16 and more reinforcement destroyer runs.

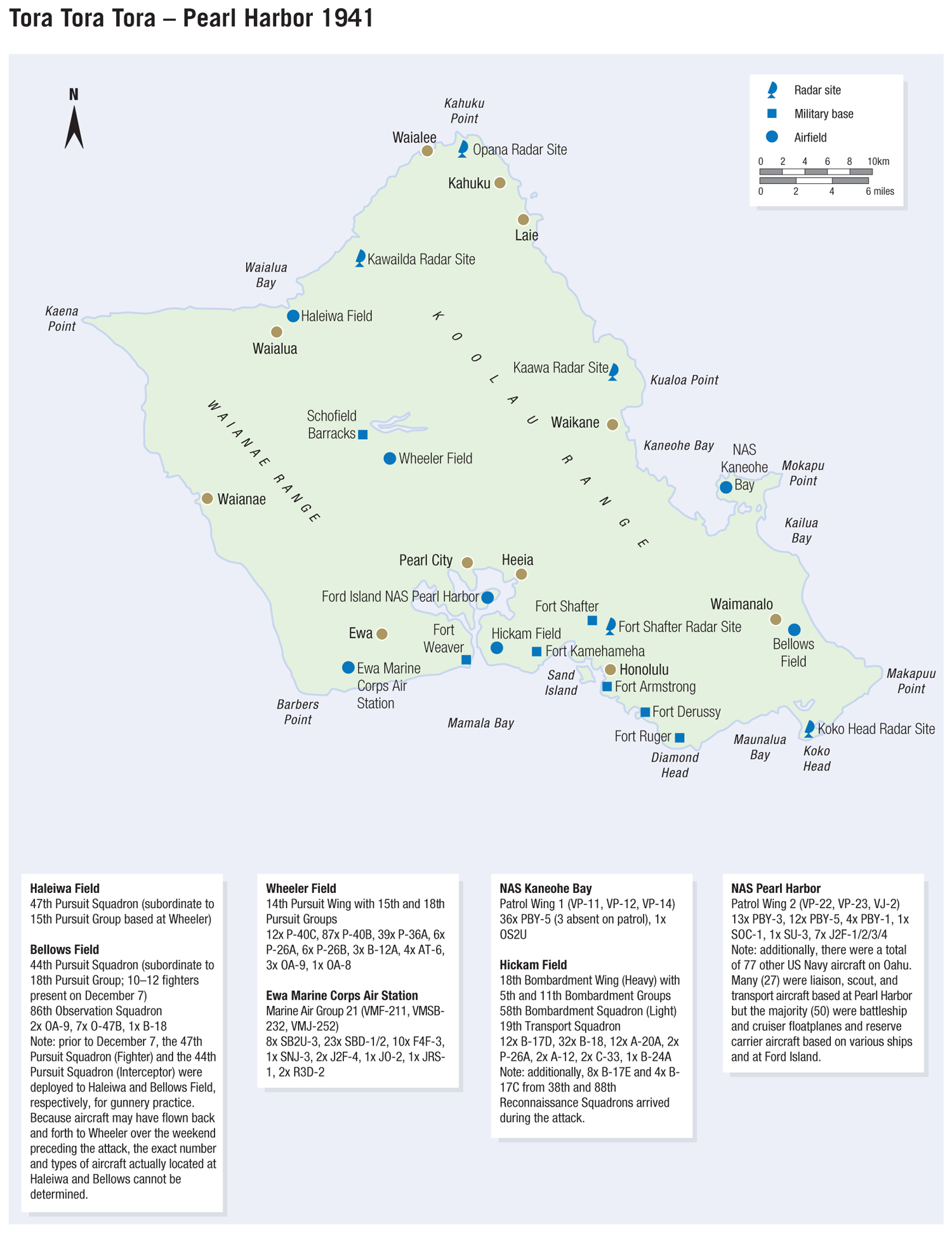

Yamamoto watches an A6M “Zero” fighter take off as part of his air offensive against Allied targets in the South Pacific, which featured four major attacks. The operation achieved little except to highlight the growing impotence of the IJN’s airpower. (Juzo Nakamura via Lansdale Research Associates)

After several delays, the Imperial Army started the offensive on October 24. The main Japanese attack finally commenced on the night of October 25–26. Despite claims of victory, all attacks were repulsed with heavy losses. Concurrent with these attacks, the IJN planned the largest naval operation yet to counter and defeat any American naval forces operating in support of the Marines. The Combined Fleet departed Truk on October 11 with a force of four battleships, four carriers, nine cruisers, and 25 destroyers. In addition, Mikawa’s Eighth Fleet added four more cruisers and 16 destroyers. After the series of false starts, Yamamoto ordered the Combined Fleet to engage the Americans on October 25.

The Battle of Santa Cruz which followed on October 26 was the fourth carrier clash of the war. It was IJN’s greatest victory over the Pacific Fleet since Pearl Harbor. The Japanese sank carrier Hornet and again damaged Enterprise. Yamamoto ordered his subordinates to seek a night battle to finish off the fleeing Americans, but their fuel situation forced the IJN to return to Truk by October 30. American losses had been high, but the Japanese had been turned back and their carrier air groups had been decimated and two carriers heavily damaged. These losses made Santa Cruz a pyrrhic victory for the IJN and prevented it from exploiting success.

The Guadalcanal campaign came to a climax in November. The Combined Fleet planned another massive effort to reinforce the island. A plan identical to the October offensive was outlined with a larger convoy preceded by another battleship bombardment to neutralize the airfield.

The scope of the operation suggests that the Japanese had finally determined that this was a decisive battle and were prepared to employ sufficient forces to guarantee success. The Combined Fleet was sure that the naval balance had swung in its favor after the great victory at Santa Cruz. The mission to neutralize the airfield was given to a force of two battleships, one light cruiser, and 11 destroyers which departed Truk to execute the bombardment on the night of November 12–13. This attempt was thwarted by a smaller American force of five cruisers and eight destroyers, which intercepted the Japanese and forced a vicious night action at close range. Losses were heavy on both sides, but the critical bombardment did not occur. Battleship Hiei was damaged and when daylight came was helplessly circling in the waters off Guadalcanal. It succumbed to air attack, becoming the first IJN battleship lost in the war.

The Combined Fleet assembled a new force to attempt another bombardment. This was centered on a single battleship with two heavy cruisers and two destroyer squadrons. Additional battleships were available, but were not employed. This renewed attempt was met by the last major American surface assets in the Pacific – two modern battleships. In another savage night battle on the night of November 14–15, the Japanese were again turned back. In the first battleship duel of the Pacific War, the Japanese lost battleship Kirishima.

These two night battles, known as the First and Second Naval Battles of Guadalcanal, were the decisive events of the campaign. While the Americans had delivered large numbers of additional troops to the island, the Japanese only delivered 2,000 troops and a meager amount of supplies. The large Japanese convoy had ended in disaster with all ten transports sunk since American aircraft from the undamaged airfield were able to intervene. Naval losses were heavy for both sides. The Americans lost two cruisers and seven destroyers sunk and many ships damaged. The Japanese lost two battleships, a heavy cruiser, and three destroyers. The IJN had been defeated more by a failure to mass its forces than by being out-fought.

The battle of attrition was too much for the IJN. On January 4, the Navy Section of the Imperial General Headquarters instructed Yamamoto to prepare to withdraw the remaining troops from Guadalcanal. The evacuation of Guadalcanal was codenamed the “KE” Operation. The Americans detected the preparations for the KE Operation and believed they were actually for another Japanese attempt to reinforce the island. The evacuation operation was carefully planned to take place in three destroyer lifts and would begin in late January.

On the night of November 12–13 1942, a large Japanese task force including two battleships headed toward Guadalcanal to conduct a bombardment of Henderson Field. In order to save the airfield from devastation, the Americans were forced to intercept the Japanese with a smaller force of cruisers and destroyers. Both sides closed until the formations were almost intermingled. At 0148hrs, the lead Japanese battleship, Hiei, used its searchlights to illuminate targets for the rest of the fleet. These lights settled on the lead American cruiser, Atlanta. This scene shows the opening moments of the most vicious night battle of the war.

The first evacuation run was conducted on February 1 with 20 destroyers. Another run with 20 destroyers was conducted on February 4. A third run on February 7 was conducted with 18 destroyers. The operation was successful and the best sources indicate that 10,652 men, most severely emaciated, were rescued. Japanese losses were a single destroyer. The Japanese attributed the success of the operation to careful planning, boldness on the part of the evacuation forces, and good air cover. It is fair to wonder why this level of commitment was not displayed when the battle was still in the balance.

With Guadalcanal lost, the focus shifted to the Central Solomons and New Guinea. In another sign of declining Japanese fortunes, in the Battle of the Bismarck Sea on March 2–4, Allied air attack destroyed a convoy attempting to move troops from Rabaul to Lae on New Guinea. To redress Japan’s declining position in the Solomons, Yamamoto devised a major air offensive to suppress the growing Allied strength in the region. He moved the air groups of the Combined Fleet’s four carriers, about 160 aircraft, to Rabaul to join the 190 aircraft of the Eleventh Air Fleet bringing Japanese air strength to some 350 aircraft. The air offensive was codenamed the “I” Operation and consisted of four major attacks conducted on Allied positions on Guadalcanal (April 7), Buna (April 11), Port Moresby (April 12), and Milne Bay (April 14). Japanese pilots claimed great success against Allied shipping and defending fighters which prompted Yamamoto to declare the operation a success and ordered its conclusion on April 16. In fact, little had been achieved. Japanese losses were heavier than those suffered by the Allies and resulted in further attrition to IJN’s precious carrier aircrews.

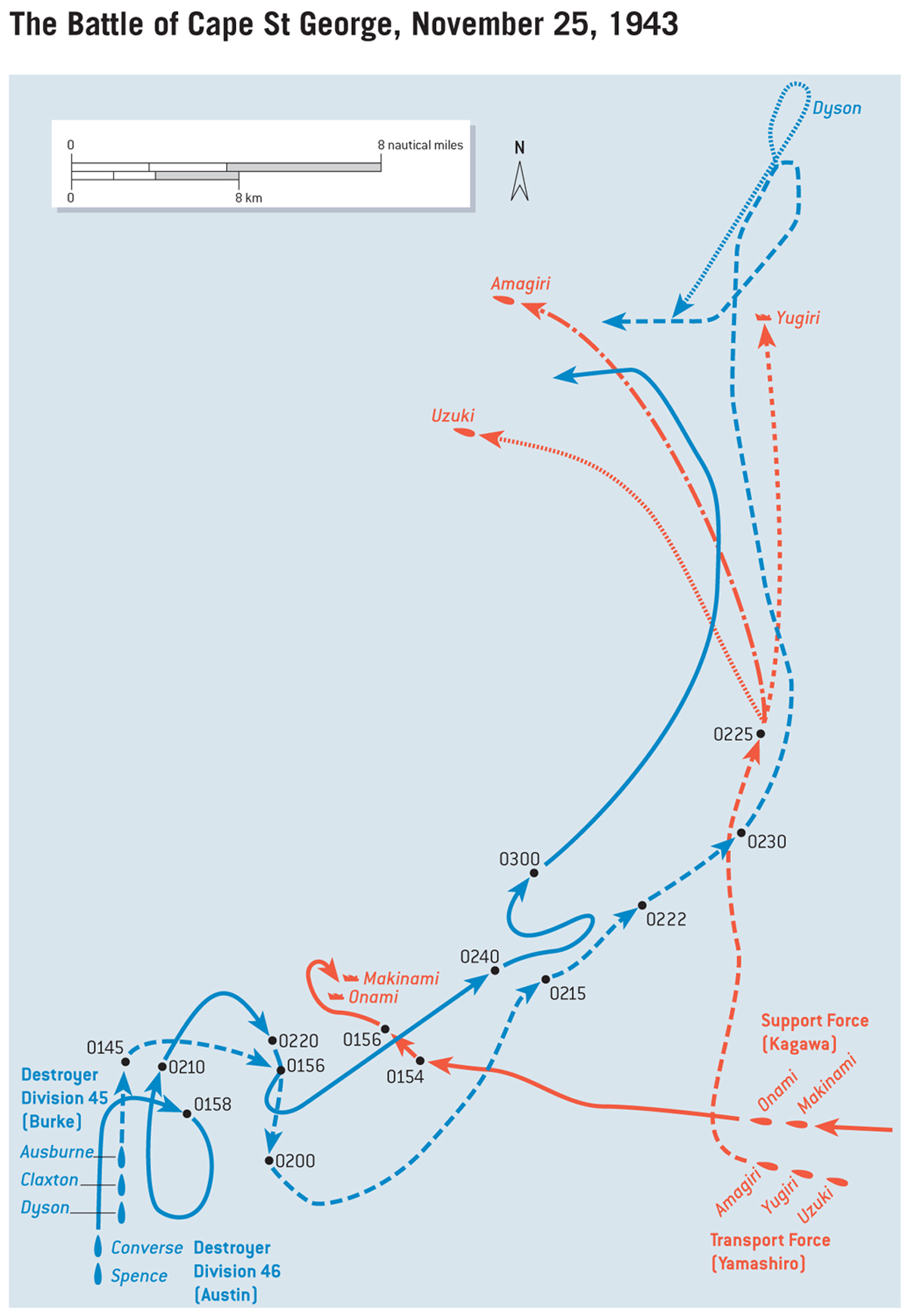

During 1943, the IJN attempted to preserve its strength in the face of two attack avenues by the Americans. In the Solomons, the action turned to the Central and Northern Solomons between March and November. During this time, the two contestants fought seven surface engagements of which all but one on the Japanese side were conducted by destroyers and light cruisers. All of these actions were fought at night during which the IJN still enjoyed an advantage. Twice, Japanese destroyers defeated an Allied cruiser-destroyer force, demonstrating to the Americans that it was not wise to use large light cruisers to chase Japanese destroyers at night.

The failure of the Japanese to reinforce Guadalcanal in November 1942 was decisive. Shown here is one of the ten transports lost in the large November convoy. (Naval History and Heritage Command)

Four of these engagements were duels between destroyers. In the first, the Battle of Vella Gulf in early August, three out of four Japanese destroyers were sunk by American destroyers using radar and a new doctrine which highlighted torpedo attacks. It was the first time in the war that the IJN’s destroyers had been beaten at night. The next action, fought on August 18, was indecisive. On October 6, the two sides met again. Japanese torpedoes shattered the American formation, but the Japanese did not follow up their advantage. The final tally of one destroyer sunk from each side was not a long-term recipe for success by the IJN.

On November 2, the IJN committed two heavy cruisers, two light cruisers, and six destroyers to attack the American beachhead on Bougainville Island in the northern Solomons. In another night action, called the Battle of Empress Augusta Bay, an American force of four light cruiser and eight destroyers intercepted the Japanese and defeated them, sinking a light cruiser and a destroyer. American losses were limited to a single destroyer damaged. It was obvious that the Japanese had lost their tactical advantage in night engagements. Adding to the IJN’s misery, when the Second Fleet arrived at Rabaul on November 5 with six heavy cruisers to “mop up” American naval forces off Bougainville, they were immediately subjected to carrier air attack. Four were damaged and forced to return to Japan for repairs and the operation ended as a complete fiasco. This marked the end of major IJN operations in the South Pacific and the end of Rabaul as a major base.

The verdict that the IJN had lost its edge in night combat was confirmed later in November at the Battle of Cape St George when a well-handled USN destroyer force intercepted five Japanese destroyers, sinking three of them at no loss. The USN now had all the requirements for victory in place – aggressive leadership, tactics which played on their superior technology, and an ever-growing number of modern ships.

As the Allies drove relentlessly north through the Solomons to neutralize and eventually encircle Rabaul, the USN was beginning a major offensive in the Central Pacific. This kicked off in November 1943 with landings in the Gilbert Islands. The IJN was forced to watch helplessly as Japanese garrisons in the Gilberts and then the Marshalls were crushed. The fallacy of the Japanese strategy of holding overextended island garrisons was fully exposed. In February 1944, the USN’s fast carrier force attacked the IJN’s Central Pacific bastion of Truk. The Combined Fleet moved its main forces out of the atoll in time to avoid being caught at anchor, but two days of air attacks resulted in significant losses to Japanese aircraft and merchant shipping. The power of the American attack on Truk far surpassed that of the Kido Butai against Pearl Harbor.

Forced to abandon Truk and unable to stop the Americans on any front, the IJN husbanded its remaining strength in preparation for what was hoped would be a decisive battle. This came in June 1944 when the Americans landed on Saipan in the Marianas, which was inside Japan’s inner defense zone. The Japanese reacted with the sortie of a nine-carrier force, led by Shokaku, Zuikaku, and the new armored-deck carrier Taiho. The resulting clash, the Battle of the Philippine Sea, was the largest carrier battle in history. Though this was the largest IJN carrier force of the war, the carrier clash did not turn out as the Japanese had planned; in fact, their decisive defeat resulted in the virtual end of the IJN’s carrier force. A series of Japanese carrier air strikes on June 19 were shattered by strong American defenses. On the same day, Shokaku was hit by four torpedoes from a submarine and sank with heavy loss of life. The Taiho was also sunk by the effect of a single torpedo.

The next day, the Japanese carrier force was subjected to carrier air attack, and suffered the loss of carrier Hiyo to air-launched torpedoes. The Mobile Fleet returned with only 35 aircraft of the 430 with which it had begun the battle. The IJN’s ultimate effort had resulted in total defeat.

After Philippine Sea, the IJN was still a formidable force, at least on paper. Of the 12 battleships commissioned before or during the war, nine still remained operational; of 18 heavy cruisers, 14 were also available. Efforts to rebuild the carrier force were unsuccessful since the training given new aviators was of an abysmally low standard. The new Unryu-class carriers never went to sea with a full air group. This left the IJN with a collection of converted carriers, led by the last Pearl Harbor survivor,Zuikaku.

The IJN was faced with an unenviable choice: to commit its remaining strength in an all-out attack, or to sit idly by as the Americans occupied the Philippines and cut the sea lanes between Japan and the southern resource areas in the Dutch East Indies and Malaya. The plan devised by the IJN attempted to play to its last remaining strength – the firepower of its heavy cruisers and battleships. In a final attempt to create a decisive battle, these were all committed against the American beachhead at Leyte Island. The only hope that this would be successful was the decision to use the remaining carriers as a lure to draw the USN’s carrier force away from Leyte Gulf long enough for the heavy units to enter and destroy any American shipping present.

The Japanese effort was expansive with five major groups totaling four carriers, nine battleships, 14 heavy cruisers, seven light cruisers, and 35 destroyers. However, the carriers only embarked just over 100 aircraft (equal to those on a single US fleet carrier) and the land-based air fleets were hollow shells which would soon begin suicide attacks as the only method to inflict losses on the Americans. In contrast, the USN brought 17 fleet and light carriers, 18 escort carriers, 12 battleships, 25 heavy and light cruisers, and 162 destroyers to the fight. The Japanese were risking annihilation.

The battle revealed the weakness of the IJN by 1944. After departing from Brunei Bay on October 20, the main battleship force (Force “A”) was attacked by two American submarines in restricted waters and suffered two heavy cruisers sunk and another crippled; both subs escaped. After entering the Sibuyan Sea, this force was assaulted by a full day of American carrier air attack. Another heavy cruiser was forced to retire, but the Americans concentrated their attentions on superbattleship Musashi and sank it under a barrage of 20 torpedo and 17 bomb hits. Many other ships were struck, but continued on.

Convinced that this pummeling had made Force “A” ineffective, the American carriers headed north to address the newly detected threat of the nearly empty Japanese carriers. So weak was Japanese naval aviation at this point that the last air strike of the war launched from the carriers against their American counterparts went unrecognized as a carrier strike. In an action known as the Battle off Cape Engano on October 25, the Americans threw over 500 aircraft sorties at the Japanese force, followed up by a surface action group of cruisers and destroyers. All four Japanese carriers were sunk, but at least this part of the Leyte plan had gone something like according to plan for the IJN.

The final major surface action fought between the IJN and the USN occurred off Samar on October 25 when Force “A” fell upon a group of USN escort carriers escorted by only destroyers and destroyer escorts. Both sides were surprised, but the outcome looked certain since the Japanese could still bring to bear four battleships, six heavy cruisers, and two light cruisers leading two destroyer squadrons. In perhaps the most unlikely action of the Pacific War, the Japanese failed to even recognize, much less press home their advantage, and were content to conduct a largely indecisive gunnery duel before breaking off. In exchange for the loss of three heavy cruisers, Force “A” sank a single escort carrier and three escorts. After this clash, the on-scene Japanese commander decided not even to attempt to execute his orders to storm into Leyte Gulf.

Just before the final action off Samar, another group (known as Force “C”), consisting of the two Fuso-class battleships escorted by a heavy cruiser and four destroyers, attempted to enter Leyte Gulf from the south through Surigao Strait. This action was fought at night, unlike the action off Samar, and was more of a maritime execution than a battle. An American force of six battleships (two sunk at Pearl Harbor and salvaged), eight cruisers, and 26 destroyers waited in ambush. Conducting a radar-guided torpedo attack, American destroyers laid waste to the Japanese, sinking one of the battleships, damaging the other, and sinking three destroyers. Naval gunfire finished off the second battleship. Only a single Japanese destroyer survived, and only a single American destroyer was heavily damaged in return. Another IJN force built around two heavy cruisers failed even to coordinate its movements with Force “C” and arrived at Surigao Strait in the middle of this slaughter. It made a desultory torpedo attack and retreated down the strait.

At the conclusion of the Battle of Leyte Gulf, the IJN was finished as an effective force. Losses were extremely heavy with four carriers, three battleships, and six heavy cruisers sunk. Most of the remaining ships suffered some level of damage, and many never returned to Japan.

Survivors of the defense of the Philippines gradually returned to Japan where almost all were virtually immobilized for lack of fuel. Following Leyte Gulf, there were only minor surface skirmishes between the IJN and USN. The last major surface engagement involving the IJN was actually fought between the heavy cruiser Haguro and the RN on May 16, 1945 near the Andaman Islands. The action resulted in the loss of the cruiser for no loss to the British. In April 1945, the Americans landed on Okinawa as a preliminary to landing on the Japanese home islands. For reasons linked more to pride than to operational necessity or value, the IJN decided to send its last surface force to attack the Americans off Okinawa. For this last effort, only a few ships remained operational – superbattleship Yamato, a light cruiser, and eight destroyers. The force departed Japan on April 6, and was attacked the following day by hundreds of American carrier aircraft. In this symbolic end, Yamato, the light cruiser, and four destroyers were sunk and over 3,600 of their crews lost before even getting close to their target. The USN lost ten aircraft in return. For the final months of the war, the USN hunted the IJN’s remaining units in port. At the time of Japan’s surrender, the once-mighty IJN had been reduced to insignificance.

This towering column of smoke marks the death of superbattleship Yamato on April 7, 1945. The demise of Yamato not only symbolized the death of the IJN’s battleship force, but also marked the end of the entire IJN. (Naval History and Heritage Command)