|  |

‘Why are you working in our garden? I bet my father made you.’

‘No, I’m—’ Phil glanced at the girl who stood beside him, but couldn’t meet her direct gaze. He kicked the pile of weeds and shrugged. ‘I only started last night. I had nothing else to do.’

‘Jeez, even if I was bored senseless, I wouldn’t weed someone else’s garden.’

‘It’s peaceful here at night and I get phone reception up here. Yesterday I, sort of, looked over and saw—’ He nodded at the garden but his voice trailed away, realising it sounded like a criticism.

‘Yeah, a friggin’ mess. Was a mess.’ The girl put a small bucket with a lid onto the ground, set a silver headlamp on top of it and checked Phil’s work. ‘This looks way better.’ He glanced across and saw a tumble of long hair, a ring in her nostril and a beautiful face. She turned to Phil with an unwavering stare. ‘Are you Phil?’

‘Yup.’

‘I’m Emara.’ She held out her hand but Phil showed her the soil on his hands. ‘Don’t worry about that,’ she said, ‘I’m a farmer.’

Phil grinned and shook her hand. There was a scratching at the fence behind them and Blue’s head appeared above the railing. She wore a big goofy dog-grin. ‘Oh, yeah. This is Blue.’

‘What the hell? Those eyes.’ Emara trampled Phil’s freshly arranged strawberry netting to reach Blue. She held Blue’s face still while she studied her eyes. ‘Heterochromia. This is amazing. I’ve only seen shades of the same colour but these eyes are something else.’ Emara let Blue’s face go and stepped back, still staring at the different eye colours.

‘She’s Dad’s prize header.’ Phil heard the pride in his voice. He leaned over the fence to stroke Blue’s umbrella ears, but she side-stepped him to focus on Emara. Each vigorous wag of her tail thumped the sides of her own body.

Emara picked up one of Blue’s front paws and shook it. ‘Hello, Dad’s prize header. You’re gorgeous, did you know?’

‘Yeah,’ Phil said, but he was looking at Emara when he said it. Her actions were confident and fearless but not intimidating like the self-assured kids at his school. He liked her wide smile and warm eyes. He liked how lovely she was to Blue.

‘Have you bred from her?’

‘What? Who? Oh yes, but it hasn’t come out in any of her pups.’ Phil concentrated on Blue then. ‘She breeds good lines and Dad wants her to have another couple of litters. If this eye condition comes through he thinks he’ll get way more money.’

Emara didn’t look at Phil when she said, ‘I heard your dad’s sick. How’s he doing?’

‘He might have improved in the last day—’ Phil heard a catch in his voice, so he shut up.

‘Good job,’ she said. ‘And how’s it been, just you and my father? Did you find him a laugh a minute?’ Phil didn’t know how to answer. He looked away and Emara said, ‘Exactly what I suspected — hilarious.’

The memory of the week’s drudgery with Chopper faded as the week in Emara’s company lit up with possibility. She flicked her hair back over her shoulder and he saw a row of earrings around the edge of her ear. He wanted to keep her talking so he looked towards the driveway on the other side of the house. ‘I saw you arrive home before. Is that your horse float?’

‘It’s our neighbour’s but Scout, my pony, used it on his road trip,’ Emara said with a laugh. ‘I’ve just turned him out into the horse paddock. I think he’s pleased to be home.’

‘Do you do events?’

‘No, way. I’m a horse-sports girl and proud.’ She gestured at the paddock down the hill where the horses were kept. ‘When you meet Scout, you’ll see how brilliant he is. He can do tricks.’

‘Like what?’

‘He can bow, give hugs, walk backwards and,’ Emara started to demonstrate a slow studied walk, ‘he can take single steps like this, right on command.’ She pointed at Blue. ‘What about Blue? What can she do?’

Blue heard her name and went into overdrive, her tongue lolled to the side and her mouth pulled back in a smile. ‘She can bark her name and write numbers — except eight — she finds that tricky.’

‘Haha.’ The sound of Emara laughing at his joke made Phil glow like a lamp. No one rated him as a funny guy. ‘Do you like horses?’ she asked.

‘I did, until Robbie ditched me. Blue and I had to walk home — on Christmas Day!’

Emara really laughed then. ‘Oh yes, that old ruse. Robbie’s shrewd. He’d have flashed his ugly old teeth in a horse chuckle all the way home.’

‘I think Chopper laughed, too.’

‘Yeah, well, they aren’t dissimilar.’ Emara dug into the soil with her toe. ‘Chopper’s not my real dad but I love him like a real dad. We used to be better mates, me and him, but we don’t agree on stuff anymore and he won’t listen to my suggestions.’

‘Like what?’

‘Just different ways to farm — more environmentally friendly ways. He thinks I’m a know-it-all, but I reckon that label should go to him.’ Emara stepped back and knocked her bucket and torch over, saving Phil from having to answer. ‘Oops,’ she said. ‘Lucky there’s nothing in here, yet.’

‘What’s it for?’

‘Slugs, snails, white butterflies, any creatures I can save.’

‘Haha. What do you do with them?’ Phil thought of all the garden pests he’d killed over the last few days. ‘I hope you don’t save those green shield beetles that stink when you squash them?’

‘I save them. I save everything and tip them out on the far side of the shearing sheds.’

He really laughed then, he couldn’t help it. ‘I don’t get it. They’ll crawl back, they’ll fly — there’s probably an army of pests on their way right now.’

She rolled her eyes. ‘You’re like Dad, he wants to kill stuff. If he sees a bug, he says, “Oh, what? A caterpillar! Let’s blast the entire garden with a broad-spectrum poison.”’

‘You don’t like sprays?’

‘No, I hate them. Pesticides harm humans and they kill everything, good and bad.’

‘What do you mean, good?’

‘Hoverflies and ladybirds. And us. We’re good!’

Phil’s mind tumbled as new ideas confronted old ones. He began to doubt the methods he and his dad used for pest control at home. ‘Yeah, who wants spray on their vegetables,’ he heard himself say. Getting Emara’s approval felt important. ‘You’ll think it’s weird but I’m totally into growing stuff, especially vegetables. My dad’s the same.’

‘Why is that weird?’

‘Gardening’s not a normal hobby for—’

‘I don’t buy into normal,’ Emara said cutting him off. ‘People care too much about that stuff.’

‘Yeah, but everyone does.’ His own life was an example of struggling to be accepted or, at the very least, not to stand out.

‘I don’t care what people think.’ Emara folded her arms and Phil admired her steel. Her attitude was letting fresh air into his thinking.

‘I could help you get those pests?’

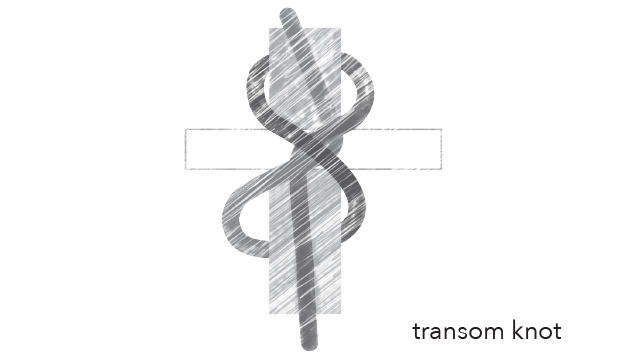

‘You don’t have to slave all day for Dad and then help me.’ She grinned at Phil. ‘But I wouldn’t mind learning how you tied that fancy knot on the tomatoes.’

Phil looked over at his work. ‘The transom? It’s the most useful garden knot you can learn.’ He rolled his eyes. ‘Believe it or not, I’m a knotter.’

‘Tell me there’s no such word.’

Phil laughed. ‘I’m a knotter and proud.’

––––––––

Tuku was in the kitchen when Phil went in for breakfast the next morning and Phil was so pleased, he could’ve hugged him. ‘You missed me, huh? Well the Kōtuku has returned.’ He grabbed another plate and shared the bacon and eggs he’d just cooked with Phil. ‘Eat that kai; you’ve probably been living on sausages and carrots. Even Bear Grylls would’ve found that week with Chopper tough.’

Phil felt puffed with pride. ‘Cheers Tuku. I’m starving.’

Blue wagged her tail from the kitchen door and Tuku went to give her a pat. ‘Have you been a good girl? Did you go mustering?’

‘No,’ Phil answered. ‘She can’t understand Chopper’s whistles so he wouldn’t let us go. I’ve been cleaning.’

‘Every day?’ He shook his head and said, ‘Shit.’

When Emara came in, she high-fived and hugged Tuku. ‘Did you have a good Christmas? I thought you might like the coast so much you wouldn’t come back.’

‘No chance. This is my kāinga.’ Tuku smiled, ‘But hey, I got you a Christmas present,’ and he gave Emara a sea shell necklace.

‘You made this?’

Tuku shrugged. ‘No big deal.’

‘It is.’ She smiled at him. ‘Thank you.’

There was no friendly greeting when Chopper walked in, just a general curt nod. ‘I want you all to listen up. This is today’s plan.’ He looked around to check he had everyone’s attention. ‘We’ll start clearing the top of the eastern ridge, work down and across the foot of the mountain and bring the mobs into Cabbage Flats ready for shearing.’ Phil nodded eagerly but Chopper shook his head. ‘Not you. It doesn’t work with your dog.’ He stared at Phil from under the brim of his hat. ‘You can start on the mess in the woolshed left over from dagging and crutching. Bag up the dags and get them onto the trailer. I’ll empty the whole lot down a tomo.’

‘What’s a tomo?’ Phil asked.

‘A tor-mor,’ Emara corrected both Chopper and Phil. ‘Not a toe-mow.’ Chopper’s face darkened and his eyes narrowed.

‘It’s a vertical cave or a drop-out,’ Tuku said. ‘This whole area is limestone country, so it’s pitted with holes we call tomo.’ Chopper tried to take back the floor but Tuku added, ‘Many of them have water running underground.’

‘And that’s why we don’t want to be chucking waste down them,’ Emara said, picking up from Tuku.

‘We’re not having this discussion, Emara.’ Chopper waved Phil away with his hand. ‘Get over to the shearing sheds and make a start.’

‘Hang on.’ Emara’s expression hardened as she confronted her father. ‘We drenched the sheep, which means there’ll be chemical residue on the dags. They’ll be contaminated. That’s going to affect the aquifers, isn’t it?’ She lifted her chin to meet Chopper’s angry expression. ‘As you say, every action has a consequence.’

‘Yes, a financial consequence,’ Chopper snapped. ‘While you waste time drying and turning that heap of rubbish, other jobs get away on us.’

‘We could donate the wool to the local school for a fundraiser.’

Emara didn’t flinch as Chopper’s eyes narrowed to slits again. ‘You think you’re a rebel with a cause, don’t you? I’ve got a desk overflowing with compliance papers and you’d like to get a bunch of school kids out here to play in the woolshed. No way!’ He chucked his coffee cup into the sink where it rolled onto its side. He turned back to Emara. ‘You leap from one crazy scheme to the next. Soon you’ll be teaching the sheep to use toilet paper sprays like that newfangled stuff you’ve put in our bathroom.’

Chopper left, slamming the door as he went and the plates rattled on the shelf.

‘What’s this?’ laughed Tuku. ‘Are we digging porta-loos for sheep? Do they use toilet paper now?’

Emara gave a sarcastic ‘haha’ but she said, ‘I’ve found this new product that’s a natural wiping aid and you’d think I was trying to turn Dad vegan.’

‘I’m happy to try it.’ Tuku laughed. ‘The spray that is, there’s no way I’m giving up meat.’

The laughter and banter between Emara and Tuku made Phil feel left out. ‘It’s not fair,’ Phil said. ‘Just because Blue follows commands not whistles.’

‘This won’t last long,’ Tuku said. ‘He’s making a point to remind us all,’ he said, looking pointedly at Emara, ‘who’s not in charge.’

‘I’ll be the boss one day, so watch out, Tuku.’ Emara turned to Phil. ‘Make out you’re having a great time over there and he’ll soon put you back on Robbie.’