|  |

‘You’re working with me today,’ Tuku called from outside Phil’s room. ‘We’re spraying the tracks. Then he says you’re to clean the dog kennels.’ The irony of cleaning out Blue’s old digs didn’t seem to occur to Tuku, who kept talking through the open door as he pulled socks on. ‘We’ll do the spraying first while there’s no wind.’

Out in the sheds, Phil yanked the knapsack off the hook and the shoulder strap snapped in his hands. ‘Stupid bloody thing,’ Phil yelled. He wanted to kick the work bench, then shout at Tuku, at the weeds, at the dumb equipment.

‘Going to be one of those days,’ Tuku said. He took the knapsack from Phil and fossicked under the bench until he found a sturdy piece of rope. ‘How about we—’

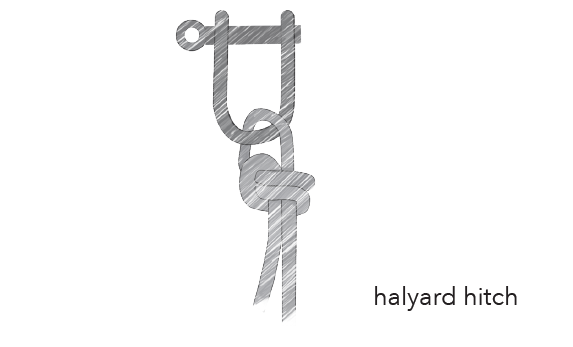

‘I can do that,’ Phil said. He took the rope and attached it at both ends of the knapsack using nifty halyard hitches.

Tuku inspected Phil’s work. ‘That’s a sailor’s knot, isn’t it? You’re pretty damn good at that stuff. We’ll see if it holds up.’ Phil shrugged then trudged behind Tuku to the gate where they split up, Phil on the left and Tuku on the right-hand side of the verge. They walked backwards, covering the weeds with spray.

‘So where is everyone?’ Phil demanded. It hurt to speak, it hurt to be quiet.

‘They left early to go and look at the tomo.’

‘Who went?’

‘Both hunters, plus Chopper and Emara. The hunters will carry on from there, I’d say. I reckon Chopper took Emara along so this spraying would get done.’

‘What do you think about the spraying?’

Tuku shook his head. ‘Not worth all the fighting, that’s for sure. They both care about the land, they both care about doing right — whatever ‘right’ is — and they both care about each other.’ He shook his head again. ‘I’m pleased to have a break from them.’

‘They could’ve taken me, it’s my dog down there.’ Phil’s voice was surly. He kicked a stone along the track.

‘Doubt it. Chopper said you were dangling over the edge with your head down the hole as if you might climb in. Crazy.’ He pumped the handle to increase the pressure in the tank. ‘I’m wondering if you know about whakaute? What that means?’

‘Respect?’

‘He tika tāu,’ Tuku nodded at Phil, ‘that’s right.’ He turned and pointed up at the mountain. ‘Māori treat our maunga with respect — great reverence actually. Whakapūnake is one of our ancestors.’ He swept his hand through the air, tracing the long, horizontal ridge of white stone that sliced through the centre of the mountain. ‘Your Blue is resting in a place of huge importance.’

‘She’s not resting. She’s alive, waiting to be rescued. She’s probably terrified. She’s trapped!’ Phil’s voice rose higher with each statement. ‘It’s not a bloody resting place.’

Tuku shrugged. ‘Easy, mate. That’ll also be why you didn’t get invited along.’

‘Stuff you,’ Phil said, tears stinging the back of his eyes. ‘I’m not doing this dumb job.’ He shook the knapsack off and dumped it on the ground then cut across the paddocks to his room.

The duvet Blue had taken a liking to lay bunched on the end of Phil’s bed and the sight of it made him stumble. He lunged into his room and slammed his fist into the wall. The pain felt good, his knuckles burnt and there was a ragged indent in the lining board that pleased him. ‘Are you alive, Blue? How could this happen?’ He dropped onto his bed, pulled the duvet up to his face and moaned and swore and cried.

Later, Tuku pushed the door open to deliver two steaming mugs of tea. ‘Hey, bro, drink this. I understand how sad you are. I feel your pain.’ He stood holding out a cup until Phil sat up and took it. ‘I know it’s not going to bring Blue back but I do want to explain what I meant. You’ve got a connection now, and remember, knowledge is power — he mana tō te matauranga.’

Phil couldn’t imagine anything about that bush-covered mountain, which either cooked in the sun or hid behind a veil of mist, that would make him feel better, but he wanted Tuku’s company. ‘Just don’t tell me this is a good thing,’ he said, in a sulky voice.

Tuku sat against the open door in the sunlight, his tea wrapped in his big hands. ‘Good? Bad? We’re not in control, mate.’ He rested his head back and said, ‘Let’s kōrero about this whenua. You know about Māui fishing up Aotearoa, don’t you?’

‘Of course, but—’

‘Tell me what you know.’ He blew across the top of his cup and waited as if he had all the time in the world.

Phil leant against the wall, his socked feet covered in dry grass and biddy bids hanging over the edge of the bed. ‘Māui was good at fishing and his brothers were jealous of him. They went to sea without him but he was hiding in the bottom of their boat and I know he had a special hook —’

‘Made from?’

‘Dunno.’

‘His grandmother’s jawbone,’ Tuku said.

‘I didn’t know that. But I know he used his own blood as bait.’

‘He tika, he punched himself on the nose!’ Tuku jabbed in front of his own nose to demonstrate. ‘Then?’

‘Māui pulled up the North Island,’ Phil said.

‘Ka pai. That’s why it’s called Te Ika-a-Māui.’

‘How is this relevant?’

‘Because our maunga, Whakapūnake, is where Māui foul-hooked Aotearoa.’

‘For real?’

‘Āe. We’re told his hook was embedded in the mountain when he fished up the land.’

‘That’s cool.’

‘It sure is,’ Tuku said. ‘I’m proud to be here as a custodian. But there’s something else that marks this whenua.’

‘Hang on.’ Phil got off his bed, pulled out his tin of biscuits and opened the lid.

‘You been holding out.’ Tuku took three biscuits. He stood up, balanced himself on one leg and bent his arms to made claws out of his hands. He puckered his mouth into a beak. ‘What am I?’

‘A weirdo?’

‘Probably, but something else too.’

‘A flamingo?’

‘No,’ Tuku laughed. ‘I’m a moa, you idiot. Moa lived round here. In fact, the remains of the largest ever moa were found just up the road in Tiniroto — three and a half metres high, they reckon. Weighed about a hundred and fifty kilos! That’s a big bird,’ Tuku smiled.

‘No way.’ Phil thought for a moment. ‘There could be moa bones down there with Blue?’ Saying her name made him wince.

‘Definitely. And kiwi, probably huia. Cavers find bones sometimes but otherwise they might just lie around for centuries.’ Tuku swallowed the dregs of his tea. ‘All this chatting will get us in trouble. Can you make a start on the kennels?’

‘What do I do?’

‘Hose them out, rake the dog shit from under the kennels and bury it in a trench at the end of the run.’

‘Do I dig the trench?’

‘You sure do, mate.’ Tuku paused with his hand on the door frame. ‘I’m off soon but I’ll be back early tomorrow. Chopper wants New Years off. Will you be okay today?’

‘I don’t know.’

Tuku stared at Phil. ‘I think you will be. You’ll find the strength to deal with all this. You’re a special sort of guy.’

––––––––

The sun beat down on Phil’s back as he hosed, raked and buried the shit. With his face hidden behind dark glasses and his wide-brimmed sunhat, he was able to cry as he needed to. When he cleaned out Blue’s kennel he was torn between climbing in and lying down or taking to it with a hammer. She’d been so miffed to be in that cage, but now she was in the most terrible cage of all. Thoughts of Blue took him straight to thoughts of his father and the vicious cycle ripped at his heart.

He heard Chopper and Emara arrive back just as he was finishing the trench. He saw them tending the horses before they walked to the house. A while later, as Phil rinsed the spade under the hose, Chopper strode purposefully towards him. Emara stuck by him like a shadow. A sheen of sweat covered Chopper’s weathered face and arms. ‘Phil? Can I have a word?’ He frowned over his shoulder at Emara as if he wanted her to move away but she kept her eyes down and held her ground. ‘So,’ Chopper started. ‘We’ve been out to the tomo to, ah, to see, to weigh up our options, shall we say.’

‘And what are they?’ Phil asked.

‘They’re not good, I’m afraid.’ Chopper wiped his face with a big handkerchief. ‘I took out some rope, at least twenty metres in length and I doubt it went anywhere near the bottom.’

‘We need longer rope.’

‘Look, son. This is far from ideal and I don’t have the answer you want. The tomo is a death trap. Two Bob said he’s seen some deep caves on his pig-hunting trips but nothing like this one.’ He wiped his mouth with the handkerchief and Phil saw it was a nervous gesture. ‘It seems to narrow in one section then maybe it widens again. Your Blue might have slithered through.’

Phil stared hard at Chopper. He had nothing to lose. ‘I’ll climb down and get her—’

‘Well, you can stop that talk right now. Under no circumstances will you be doing anything so stupid. The only people idiotic enough to climb down those holes are cavers and I’ve just rung them — the Speleological Society — but, as I’m sure you’ll appreciate, New Year’s Eve isn’t the best time to be getting hold of people, let alone a caving expert.’ He paused and wiped his mouth again. ‘But I will try again.’

‘When?’

‘It’ll have to be next week.’ Chopper looked hard at Phil then spoke softly. ‘Dogs are remarkable creatures and if your Blue is alive, which I’m afraid to say she probably isn’t, she’ll last ‘til then.’

‘If today is Saturday—’

‘Yes, but not an ordinary Saturday. It’s New Year’s Eve. We’ve got friends coming over tonight and I can’t spend any more time on this today. You’re very welcome to join in the, ah, party.’ Chopper looked uncomfortable. He looked somewhere over Phil’s head. ‘I know it’s not the same — but a friend who has a top breeder bitch due to have a litter of pups in a month, might be calling in tonight and I’ll ask if I can buy you one.’

‘Blue isn’t my dog. She’s Dad’s.’

‘I know. I’m sorry. It shouldn’t have happened.’

‘I can’t go home without her.’

‘I’ll give your Dad a ring—’

‘No!’ Phil gulped. ‘I’ll tell him. I’ll go home, maybe Monday. Definitely next week.’

Chopper stared at Phil through narrowed eyes. He spoke in a low hard voice. ‘We’ve all seen the drop, you could die down there. You are not to go near it.’

‘I wouldn’t know where it was,’ Phil said, avoiding the lie.

‘Right then. Think about the puppy; it’s the least I can do.’ Phil couldn’t even nod. ‘I’m getting that tomo fenced off,’ Chopper continued, more to the mountain than Phil. ‘Hopefully this terrible thing never happens again.’ He started to walk away but put his hand on top of the dog run, landing on Blue’s kennel, by coincidence. ‘There’s an old saying in the farming world: no farm dog dies of old age.’

He left then and Emara said, ‘We’re on our own. That’s bullshit about getting a caver next week because he knows all the cavers head to Mt Owen every January. He doesn’t care about Blue and he’s not going to save her.’

‘She’s the best dog our family’s ever owned and she could be lying there injured.’ An image of her perfect face so full of personality came into his mind. The way she tilted her head when someone spoke to her as if she were really concentrating. Or the way she gave big dog-sighs of contentment when someone stroked her coat. ‘I’m getting her back.’

‘Of course,’ Emara said. ‘No question about it.’