|  |

The party noise went on for hours. The adults drank heaps. There was singing, sometimes to a guitar, sometimes to the sound system Chopper had set up.

Phil mostly stayed in with Oliver, and when he did make a brief appearance at the party, Chopper and Penny looked uncomfortable. Phil could tell Skip wasn’t giving off the same vibe of abject misery.

Emara smuggled out more lengths of rope and lugged away the sections that were knotted and ready to stow with the saddles. She brought Oliver and Phil food and drink, and Phil stashed the leftovers into the backpacks arranged along his wall. He folded the sheet off his bed into Skip’s backpack and added a small piece of rope Skip could use to tie the sling shut.

Skip did his share of lifting and gathering too, but only for Emara. He stuck by her side and offered his expert advice whenever an opportunity arose. He helped Phil smuggle Oliver outside to pee then paused inside Phil’s room as Phil settled Oliver into bed. ‘Don’t leave me,’ Oliver whispered.

‘I’ll be here all night,’ Phil said.

Skip nodded in approval. ‘Yeah, I’ll go and hang with Emara and you keep Oliver company.’

When he’d gone, Oliver said sadly, ‘I think she’s Skip’s girlfriend, now.’

‘She was never my girlfriend and you need to cheer up or you’ll get sick.’

‘And then I’ll die?’

‘My God, Oliver! You’re starting to freak me out.’

‘Aunt Lily said she’s praying for our family, but we have to do some of the work ourselves.’

‘We are doing the work. We’re making sacrifices by missing Christmas and leaving home and not complaining. All that stuff is harder than saying prayers.’ He picked up the sleeping bag Oliver was lying in and rolled Oliver onto his side. ‘Are you comfortable? Or would you prefer to sleep this way?’ Phil flipped Oliver like a pancake which made Oliver laugh.

There was a knock at the door. They froze. ‘It’s me, Penny. Just checking you’re okay.’

‘Yes, thanks.’ Phil looked around the room at the half-packed bags and the pieces of rope. ‘I’m in bed now. Just playing some old videos of my little brother from last Christmas.’

‘Wouldyouliketochat?’ Her words slurred together.

‘Tomorrow,’ Phil called. ‘Thanks, though.’

‘Goodboy. Sad. Sosorry. Morrow.’

‘Thanks Penny.’

‘She sounds drunk and kind of nice,’ Oliver whispered.

‘I think she is both of those.’

‘Then why is she leaving Blue to die if she’s nice?’

‘There it is, Oliver. The million-dollar question.’ Phil lay down beside him. ‘It’s too big for tonight. Get some sleep and I’ll be here beside you.’

––––––––

Oliver fell asleep and made snuffling noises like a baby hedgehog. Blue had been a noisy room mate too, her legs used to work as if she were running. Sometimes Blue whimpered or growled in her sleep. He wondered how she was doing.

Thoughts of Blue kept Phil focused. He went through the stages of the rescue and his knots over and over until he knew he had to succumb to his tiredness. His eyes felt gritty and he’d just stretched out beside Oliver when there was a soft knock at his door. Emara whispered, ‘Are you awake?’

Phil was instantly alert. He quietly opened his door and stepped out onto the verandah. Emara was back in the shadows and Phil went to stand with her. ‘Is everything okay?’

‘Yeah, I came to check on you.’

‘It’s been a huge night with a nine-year-old for company but I’ve made it.’

She chuckled. ‘You’re a decent brother.’ She nodded at the house. ‘I’m pleading exhaustion now. Mum’s surprised I don’t want to see the New Year in, but I said it doesn’t feel right.’ A chorus of voices singing to an old-school song about a doggie in the window filled the night. They smiled at each other. ‘Music doesn’t get much worse than that,’ she said. ‘Are we all ready for tomorrow?’

‘As ready as we can be.’ A warm late-night breeze blew between them. ‘Where’s—?’ Phil didn’t want to say Skip’s name.

‘Talking to someone. Two Bob, I think.’ Emara looked at Phil. She was close enough that he could see the flecks in her brown eyes. ‘Happy New Year,’ she whispered.

‘Yeah,’ Phil said. He thought that if ever there was a time he could kiss someone this amazing, surely it was—

‘Yeah,’ she imitated his word and then Emara closed the gap. He felt her fingers on the side of his face and her mouth on his. ‘See you at four thirty,’ she murmured into his ear and then she was gone.

––––––––

Phil lay awake for a long time after that. She must like him. Surely, she liked him! Was that kiss just for him or would Skip get one too? She’d never kiss Skip. His head spun, he couldn’t switch his brain off. She definitely liked him and he sure as hell liked her.

Phil was hurt Skip hadn’t checked in. He wanted to thank him for coming out and get him to understand that it wasn’t Phil’s fault Blue had fallen down the tomo. He’d wanted to talk about Dad and he wanted to say, happy New Year’s and maybe things will get better. But Skip didn’t call by and the not speaking hurt his chest, the way it always hurt.

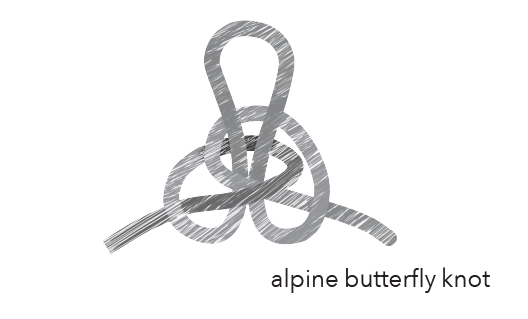

Phil’s sleep was tortured when it finally did happen. He dropped a rope over the edge of the tomo with an alpine butterfly knot tied onto the bottom and felt Blue grab it with her teeth. It was like fishing off a boat and he reeled her in. But when his catch came into sight it was Oliver clinging to the rope by his teeth. Oliver opened his mouth to say ‘save me’ and plummeted to the bottom again. Phil was drenched in sweat when his phone alarm vibrated against his skin at four o’clock.

He got up immediately, calling to mind his father’s saying, the surest way to sleep through an appointment is to try and grab a few extra minutes. Anyway, it was good to escape the nightmare.

He’d stepped outside his room when he heard Skip stumble off the bottom step of the verandah. ‘Shit,’ Phil murmured and stepped back into the shadows. Almost immediately, the room beside the step lit up and the door swung open. Two Bob stood, for what seemed a long time, silhouetted against the light, dressed in a white singlet and loose boxer shorts.

Phil didn’t move. Now he was going to be late and he couldn’t send a message to Skip or Emara. Two Bob shuffled further out of his room. He looked down at the steps and peered around the corner before there was the unmistakeable sound of him peeing onto the dry, dusty ground. Yuck, Phil thought. That’s disgusting. He finished with a resounding fart then went back into his room. It was hard to know if Two Bob was suspicious and on duty or if he’d just randomly woken up and now gone back to sleep, but there was no option. They had to take a punt. Phil crept out and around the back of the quarters.

‘I missed the step,’ Skip whispered, when Phil finally caught up with him.

‘Yeah, you woke Two Bob.’

‘I’ve hurt my bloody ankle.’

‘Not far to walk,’ but Phil saw he was limping heavily and his breathing was laboured in the morning quiet as they walked up the hill. Phil took Skip’s rope to lighten his load.

Emara had brought the three horses, one by one, down to the monkey puzzle tree, after getting them saddled. ‘Come on, we’re running late,’ she hissed. ‘They’ll have time to catch us if we don’t hurry.’ She threw the reins at Skip. ‘Take Rio.’

Phil rubbed Robbie’s nose then slipped him a piece of apple. He was rewarded by a snort of appreciation, and an obedient horse. Rio, though, was skittery and intractable, so Emara said, ‘Swap. Have Scout.’

‘I can manage,’ Skip muttered.

‘You’re wasting time.’ Emara switched reins by snatching and shoving.

Scout showed off his youth and personality by swishing his tail and stepping out, as opposed to Rio who followed reluctantly, surprised at the early start to his day. Emara opened the gate without clanking the metal so they could lead their horses through, but Skip said, ‘I can’t walk — my ankle,’ and he grabbed the pommel to swing himself up onto Scout. ‘What the hell?’ he asked when he first negotiated Penny’s Western saddle, but he was soon used to it and began riding like a cowboy in no time.

Meanwhile Rio misbehaved, even for Emma, stamping his back hooves and shaking his mane as if he wanted to throw his rope off. Then he stopped completely. She tapped him with her piece of alkathene pipe but Rio turned his head away. ‘Do you think you’re king this morning?’ Emara pulled his head back around and tapped him again but Rio wouldn’t move at all, so she tapped his hindquarter, lightly at first, then progressively harder until Rio started forward. She stopped tapping immediately and patted his head. ‘Good boy.’ Each horse had a coil of heavy rope draped over their saddles. ‘He’s not happy about the load,’ Emara said.

‘Is this light nautical or civil?’ Phil asked Emara when they were far enough away from the buildings.

‘Nautical. It’s still pretty dark so the sun is twelve degrees below the horizon,’ she laughed. ‘I love random facts like that.’

The morning gradually lightened, the sky changing from blue-grey to tinges of pink and pale blue. The riders followed narrow tracks that wound around the hills, often just massive boulders, that leaned over to shelter the trails. Phil saw tomo lying at the bases of these boulders and wondered how poor Blue was faring.

But it wasn’t all spooky and strange. As the day became lighter they saw swathes of farmland and bush that ran for miles in various directions. At the top of a steep rise Skip gave a low whistle as he took in the landscape. ‘It’s a hell of a place,’ he said, more to himself.

Emara, riding in front, shouted back proudly, ‘There’s no other place like it in the world.’ She called for a break. ‘This is the last decent water hole for the horses,’ and she pointed to, literally, a hole with water in it.

‘Where’d this come from?’ Skip asked. ‘How come water is just sitting here?’ He scanned above him for a stream running through the gully.

‘It runs underground; that’s why the hills are so porous and full of holes,’ Emara said.

‘Creepy,’ Skip peered into the water. ‘Is it deep?’

‘I’d say so.’ Emara prised a rock from the ground and threw it in. It dropped from sight. ‘It’s beautiful until it’s dangerous and then it’s creepy. Poor Blue, she’ll be desperate to get out.’