CHAPTER 3

AS A RULE, LESS IS MORE

There is nothing men will not do, there is nothing they have not done, to recover their health… They have submitted to be half-drowned in water, and half-choked with gases, to be buried up to their chins in earth, to be seared with hot irons like galley-slaves, to be crimped with knives, like cod-fish, to have needles thrust into their flesh, and bonfires kindled on their skin, to swallow all sorts of abominations, and to pay for all this, as if to be singed and scalded were costly privilege, as if blisters were a blessing, and leeches were a luxury.

Oliver Wendell Holmes

In sections of southern France, many a church displays a statue of a saint pulling up his robe to reveal a skin lesion (a bubo) on his thigh. A dog stands by his side, typically offering a piece of bread held in its mouth. This Catholic figure, Saint Roch, is generally not well known elsewhere, unless you watched the film The Godfather Part II, in which he is displayed in a procession through New York City’s Little Italy.

Saint Roch, known as a protector against contagious diseases, was born at the end of the thirteenth century in Montpellier to the wife of the governor of that city. On the death of his parents, when he was 20, he gave away all his worldly goods to the poor and began life as an itinerant pilgrim. But it was during the epidemic of the bubonic plague that St. Roch found his calling. He moved about among public hospitals in plague-ridden cities in Italy, reportedly effecting cures by his touch.

Soon, however, he fell ill with the plague. Upon being expelled because he was ill from the town in Italy where he had wandered, he isolated himself in a nearby forest, where he reportedly cured himself by simple living and the help of prayer. A dog belonging to a local huntsman came upon St. Roch and is said to have brought him bread each day so he would not starve.

St. Roch’s career as a healer was cut short when he returned to Montpellier. He was arrested and jailed as a spy, and unable to cure unjust incarceration, he languished in prison until his death 5 years later. It was his healing work, which did not call for excesses of intervention but rather simple care and belief, which earned him a place in the pantheon of saints.

First, Do No Harm

When a disease defies efforts at cure, because it is not well understood or its therapeutics remains limited or rudimentary, there is a powerful human tendency to up the ante. Do more, do something radical, take unusual measures to effect improvement are among the human drives to be reckoned with because they provide help infrequently and often have unwanted and problematic effects. Primum non nocere, first, do no harm, is the first law of medicine. It is unfortunately a law that is violated more than the speed limit in most states. For psychiatry and mental health, general medical care as well, being able to do less is a secret that has been eclipsed by too many heroic efforts to do more. As a rule, less is more.

Medications

Susan Long was a rising star in her profession in her late 20s when she came to see me in my office at the Massachusetts General Hospital in the late 1970s. As she earned greater advancement and success, she grew more anxious and afraid to leave her home. Her anxiety became so severe that it threatened her job and totally shut down time with friends and dating. I recommended a course of psychotherapy to work on what might be underlying problems stirred up by her achievements and medication treatment in light of the severity of her symptoms and the risk they posed for her livelihood.

This was a decade before Prozac and the other serotonin-enhancing drugs that I would be able to prescribe. Tranquilizers like Librium and Valium were around, but neither Ms. Long nor I was keen on employing them because of their often troublesome effects on mental clarity and wakefulness, as well as the susceptibility of our bodies to become dependent on benzodiazepines. Tricyclic antidepressants were available (like imipramine), but they had a host of lousy side effects (like blurred vision, dry mouth, and constipation) and were not all that effective for the symptoms she had. However, there was a class of drugs, monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs), then far more popular than today, which I was familiar with and suggested she try. I explained these types of medications and their potential risks and benefits to her. I said that perhaps over time therapy would help, but her concerns about imminent job loss because of her dysfunction made Ms. Long want to start on a medication, at least for now.

I wrote a prescription for Nardil, one 15-mg pill twice a day, increasing to three times a day on day four after she started this medication. We scheduled a meeting for the following week to begin therapy and review how she was doing with the medication. Late on the fifth day after she began taking the drug, she left me a phone message asking to speak with me as soon as possible. I promptly called and found her at home. “Doctor,” she said, “I had to crawl to the phone because if I stand up, I’ll surely pass out!” She was experiencing postural hypotension, a big drop in her blood pressure when she stood up and a side effect of Nardil. I had made her worse before she stood a chance of feeling better.

I explained what was happening and how to manage the symptoms (a lot of fluids, a little salt, and rising to a standing position very slowly) until her blood level of the drug naturally diminished by simply not taking any more. That worked. But Ms. Long was very reluctant to resume the Nardil and stay on it for the weeks needed to see its potential beneficial effects. I was concerned that I had caused problems that would interfere with recovering from debilitating anxiety and keeping her job!

But she was a trooper, and I had gained some of her trust. A week later, she resumed taking Nardil but only one 15-mg pill/day; we monitored her response very carefully and increased the dose when she felt comfortable doing so. It took a bit longer, but she got to 45 mg/ day and began to notice reductions in her anxiety and improvements in her ability to leave home, to be at work and among her colleagues, and to socialize.

That was an important lesson for me, and one that physicians (and now prescribing nurses) have to learn: start low, go slow when it comes to many a medication. Less was more for Ms. Long until she could tolerate more and derive a therapeutic effect and thus not abandon a treatment that would work for her.

Sixteenth-century battlefield.

© Michal Ninger. Used under license from Shutterstock.com.

Psychotherapy

This same principle of less is more can apply to psychotherapy as well.

In 1986, my good friend and colleague Dr. Bob Drake and I published a pair of articles on the “negative” effects of intensive psychological treatments of schizophrenia (Drake and Sederer 1986a, 1986b). We used as a metaphor surgical wound healing.

Ancient Egyptian doctors understood, and inscribed on papyrus dating back to 1700 B.C., that wounds did best when debris was removed, when they were gently washed with water, and when they were covered to allow natural healing. Less was more. But in the fourteenth century, the ancient ninth-century Chinese invention, which would cause more damage than about anything else man-made up until that time, became more widely implemented in Western warfare: gunpowder. Men were shooting one another at a brisk rate. To treat gunshot wounds, which frequently become infected, surgeons employed far more aggressive means of treating wounded soldiers: they poured boiling oil into their wounds. The results were, as you can imagine, disastrous. However, this barbaric practice did not end until 200 years later when a French army surgeon rediscovered the gentle and simple care of wounds—but only after he ran out of oil. A destructive tide had been turned back, fortunately, and the idea that less is more again prevailed. Gentle cleaning and protection resumed being, after two centuries of horrific treatment, the standard of wound care and has remained so today.

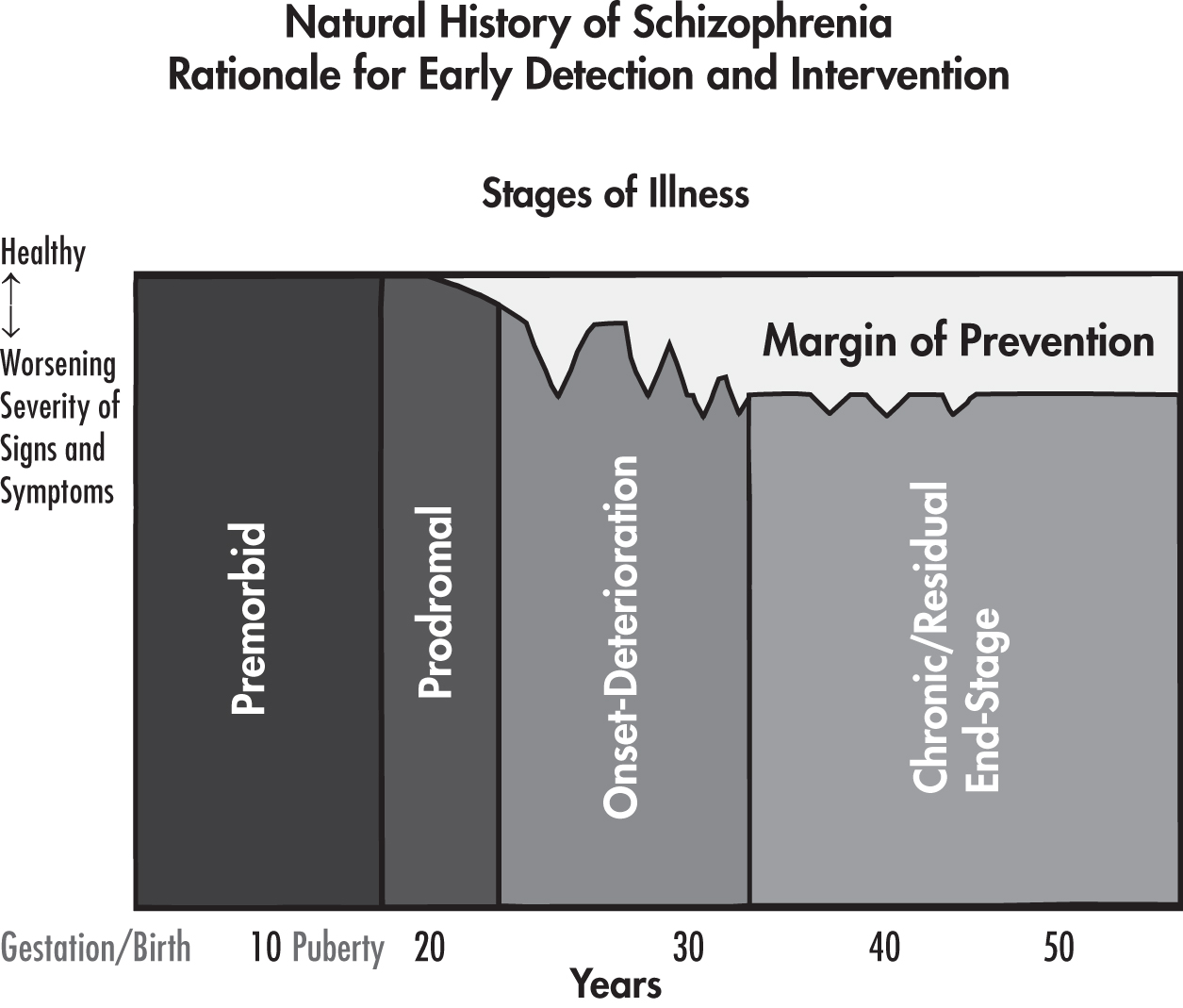

Schizophrenia affects about 1% of the world’s population. It usually has an onset in adolescence or early adulthood, with psychotic symptoms of hallucinations and delusions appearing at the outset, accompanied by social withdrawal, severe anxiety, and loss of everyday functioning at school, home, and work. In recent years, psychiatry has rediscovered that people with this serious mental illness can improve over time, even if they still have residual symptoms of the condition. Recovery, healing, is possible but requires that treatments not aggravate a person’s mental state or drive them away from the prudent, gentle care that can make a valuable difference in their lives.

In our articles (Drake and Sederer 1986a, 1986b), we reported on how intensive psychotherapy (delivered either too frequently or in an emotionally confrontational, unstructured, or deeply explorative fashion) can produce unnecessary and overwhelming psychic stimulation in vulnerable patients and induce regression, including further loss of reality testing and functional capability. Group therapies that are provocative—that urge the expression of anger and other intense feelings or evoke excessive self-disclosure—can also be toxic to people with impaired cognitive functioning and confusion about boundaries relating to themselves and others. Family therapy, too, that invites expression of conflict and feelings or is blaming or judgmental (of patient or family) has negative effects on the mental state and the course of illness of people with schizophrenia.

Instead, practical, problem-solving therapies are helpful, as are psychoeducation and providing self-management and social skills training. These are the gentle, less is more approaches that allow for improved functioning and a path to recovery in people with this serious mental disorder.

Early-Onset Psychosis

One hundred thousand, approximately, teenagers and young adults, male and female, of every class, ethnicity, and race in the United States annually experience the first onset of a non-drug-induced psychotic illness, like schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder (the latter being a disorder in which psychotic symptoms are present in addition to serious mood problems).

Until recently, if a young person became psychotic, it was commonplace that years went by before their condition, even if it was obvious to those around them, was recognized and properly diagnosed and the individual received some form of psychiatric treatment. Delays such as this (referred to as duration of untreated psychosis) have been shown to be highly associated with a more severe course of illness and greater disability over a lifetime.

For those who found treatment (or, more likely, their families found it for them), the convention has been the prescription of high doses of antipsychotic medications and a long wait for a case manager at a mental health clinic where others with more advanced stages of psychotic illness would come for their medication or monitoring. Few youths could tolerate the sedation, muscle tightness, and restlessness that high doses of antipsychotic medications produced, especially in young men. Witnessing the chronicity in patients who were decades older was alarming and repellent to their self-image and hopes. The absence of a program aimed at recovery was anathema. It was no wonder few returned for services, ironically fating them to exactly what they and their families feared the most: a life lost to illness.

However, preceding the introduction of early psychosis treatment programs in the United States, countries such as Australia (led by the Australian of the year in 2010, Dr. Patrick McGorry), the United Kingdom, and Denmark had already been at work providing a dramatically different approach to early-onset psychotic illnesses. And now, in the United States, new programs such as NAVIGATE and OnTrackNY, led by Dr. John Kane (at Northwell Health) and my gifted colleague Dr. Lisa Dixon (at the New York State Psychiatric Institute and Columbia University), respectively, are changing the trajectory and preventing disability in those youths who become ill with psychosis. These are programs trying to help young people recover and have lives they might otherwise have been denied.

Duration of untreated psychosis and later disability.

Adapted from Lewis and Lieberman 2000.

Under the rubric of Recovery After an Initial Schizophrenia Episode (RAISE), a research initiative of the National Institute of Mental Health, or the coordinated specialty care program (CSC), a recovery-oriented treatment program specifically addressing first-episode psychosis, both NAVIGATE and OnTrackNY were introduced to eschew the conventional care of psychosis, namely, too much medication and too little else. Less medication can be more when it is provided in natural settings, with the support of families, and with special attention from educational and vocational specialists to keep youths in school or work and put them on a path to the normative goals of young adulthood. It is not that RAISE and CSC are antimedication; we know that relapse is highly likely unless people take antipsychotic medications early in the illness of schizophrenia. However, modest doses and careful attention to minimizing any uncomfortable side effects informs prescribing practices. In addition, stress-reducing and health-promoting practices like meditation, yoga, exercise, healthful diet, and nutraceuticals are recognized as welcome allies, not odd practices to be scoffed at.

In his blog, the Director of the National Institutes of Health Dr. Francis Collins wrote the following:

A great example is the Simpson family, which lives just outside of Lansing, MI. At age 17, son Collin was hospitalized to work through his first psychosis, receiving what his father Tom describes as “generic care.” When Collin was released from the hospital, Tom says he felt utterly unprepared to arrange the aftercare and take steps to reduce risk of a relapse. He tried to find a psychiatrist in Lansing for his son, but he couldn’t locate one who was available to see new patients. That’s when Tom’s sister, who worked in community mental health, suggested that Collin enroll in NAVIGATE.

Tom calls NAVIGATE’s individualized, team-based approach “a godsend.” Collin not only received timely psychiatric care and careful monitoring of his medications, he also got help to prepare and pass his General Educational Development (GED) test, guidance in drafting his resume, and assistance in finding a job. Meanwhile, Tom and other members of the family participated in the NAVIGATE educational program and got their questions answered about psychosis, schizophrenia, and what they should and shouldn’t expect from Collin. “We would have been clueless if they hadn’t brought us all in as a group,” Tom says. “It was a critical part.” (Collins 2015)

I like to think of early psychosis treatment programs as characterized by less reliance on medication, less neglect, less distancing from family, and less clinic- and hospital-based care. Less is replaced by a more comprehensive set of services delivered at homes, community centers, playgrounds, and even McDonald’s and a resilient, recovery-oriented view of the future. Less medication and monitoring is more when comprehensive treatment aligns with what the person under care is age appropriately seeking. In these ways, less becomes a lot more. What’s more, so to speak, over time, RAISE and CSC programs may not even require more money if costly hospital and emergency services are reduced, as we are already seeing in the programs underway in New York State. In time, we may also see reductions in criminal justice, shelter, and welfare costs as well. Less money spent unnecessarily for crisis services leaves more for school, rehabilitation, and recovery.

Less can be more when the treatment that is delivered discards practices of limited effectiveness and with too many adverse consequences but only when complemented by comprehensive services—where necessary services are coupled with sufficient services—including those based on the goals of recovery and provided in ways and in settings where those served are comfortable and are willing to engage. That’s a secret worth spreading.

Clinical Antipsychotic Trials of Intervention Effectiveness (CATIE)

In 2001, the National Institute of Mental Health launched the largest federally funded study ever of psychiatric medications, the Clinical Antipsychotic Trials of Intervention Effectiveness (CATIE). Its purpose was to compare the older, so-called first-generation antipsychotic medications, with the newer second-generation drugs.

Nearly 1,500 patients, ages 18–65 years, with schizophrenia were enrolled in this study at 57 clinical sites in the United States. Perphenazine (Trilafon) was used as the first-generation agent (to represent others of its vintage like haloperidol, chlorpromazine, and fluphenazine). Olanzapine (Zyprexa), risperidone (Risperdal), quetiapine (Seroquel), and ziprasidone (Geodon) were the second-generation agents used; they were assigned randomly, and appeared as identical-looking capsules, to study participants. At the time, all of these second-generation antipsychotics were drugs under patent protection and were vastly more expensive than the generic perphenazine. A second phase of the study sought to examine those patients who discontinued medication because it did not work or because the side effects were intolerable; in this circumstance, another medication, clozapine (Clozaril), was added to the roster of agents prescribed (Lieberman and Stroup 2011; Swarz et al. 2008).

The results of the CATIE studies, published in more than 80 scientific articles, a book, and many commentaries, were, first, astounding in what they revealed and, second, had dreadfully little impact on practice.

The most disturbing finding, which actually did not surprise most clinicians who treat people with schizophrenia, was the incredibly high rate—74% of patients (ranging from 64% to 82% depending on the drug)—at which the study participants stopped taking the medication prescribed. Many patients continued in the study taking a different medication, suggesting that the problem was not noncompliance. While opinions vary, there is a general view that stopping medication was the result of the limited effectiveness of a given drug as well as its troubling side effects.

Medication nonadherence, patients not continuing to take what is prescribed, is a very familiar problem to practicing mental health clinicians and to the loved ones of people with schizophrenia and other serious mental disorders. First, as mentioned, patients tend not to like the side effects of the medications, which can be very different from first- to second-generation antipsychotics. The former are notorious for producing akathisia, a feeling of awful restlessness that can get so bad that there are reported cases of suicide associated with it, as well as Parkinson-like symptoms such as shuffling gait, flat emotions and facial expressions, muscle tightness, and even drooling. The second-generation antipsychotics are notorious (although this is not communicated well enough, especially by pharmaceutical companies) for producing weight gain (not just a few pounds but tens of pounds), leading to insulin insensitivity and type 2 diabetes as well as disturbances in blood lipids, like cholesterol and triglycerides, which are harbingers of atherosclerosis in heart and brain arteries. All of the second-generation antipsychotic medications can sometimes cause significant sedation, apathy, loss of libido, and sometimes akathisia as well. Second, if a person has an illness that interferes with their capacity to appreciate that they are ill, why in the world would they take an unpleasant drug for an illness that others, like their parents, say they have, but they do not think they have. Finally, it is difficult to view medication as a blessing when an individual with a mental illness faces the prospect of contending with a lifetime of chronic illness. Putting a pill in your mouth can be a painful reminder of that reality.

The most controversial finding of CATIE was that no significant differences were found in how effective perphenazine was compared with the other four drugs in the first phase of the study. I recall when olanzapine and the other second-generation drugs received U.S. Food and Drug Administration approval and were marketed for the treatment of psychosis. They were heralded as “breakthrough” medications, welcomed by prescribing doctors like me for our patients, as well as by patients and their families, because they would not cause akathisia, drug-induced parkinsonism, and tardive dyskinesia (a late-onset movement disorder). Moreover, marketing for what was to become annual sales of billions of dollars for each new drug advertised that the second-generation agents would help with the negative symptoms of schizophrenia (like loss of motivation and apathy) as well as improve the cognitive deficits in executive mental functioning (like deterioration of attention, focus, memory, and task sequencing) that are so common when the disease becomes chronic. We would have more medication treatments—more would be better for sure. But more, CATIE revealed, was, in fact, not more in terms of treatment, and actually, often it was less.

An important measure of the utility and value of a medication (or any other treatment) is called cost-effectiveness. This means the clinical and social value that will derive from spending, say, a dollar on one treatment versus another. The escalating cost curves of medical care in this country scream out to legislators and citizens; we are spending nearly 20% of our gross national product on health care. That means there is less for education, roads, safety, housing, food, and other necessities. What’s more, little of this huge health care budget is spent on prevention or early intervention—protecting the health of a population or mitigating early on the course of an illness. CATIE showed that an inordinate amount of money was being spent on second-generation medications that, overall, bestowed no greater therapeutic benefit on those who took the medications. Billions and billions of dollars, every year, funded the pharmaceutical companies, not community-based mental health services; CSC programs; and rehabilitation, skills-building, and recovery programs. More, a lot more, was being ill spent on second-generation, high-priced antipsychotic drugs when an equally effective, and far less costly, medication might do just as well.

There was one drug, clozapine, which proved itself more effective for those patients who did not respond to first-generation and other second-generation antipsychotics. Clozapine was approved for use in the United States in the late 1980s; it was expensive then and in short supply and raised many fears because of its rare but potential side effect of shutting down the bone marrow’s production of white blood cells, thus rendering a person extremely vulnerable to infection and death. That was then. Now, its highly regulated dispensation, with registries and required blood monitoring of white cell counts, has made this danger to the patient’s marrow virtually nonexistent; in fact, today more people die from clozapine-related bowel paralysis (also avoidable) than from an infection that is a consequence of a weakened immune system. Clozapine has been off patent for a long time and is inexpensive. This is an instance when more, a different type of medication, is actually more, rather than more of the same.

However, psychiatric practices have not followed the evidence that CATIE revealed. Second-generation antipsychotic drugs, the mainstay of expensive “me-too” products, continue to proliferate and cost as much as 100 times more than generic, first-generation and (now) second-generation generic drugs. Commentators about CATIE, as well as many families, remark about significant improvements or greater tolerability with newer medications and appropriately urge access lest a person with a serious mental illness be denied what may be working or might work. But psychiatric prescribing practices have not seen any increase in the prescription of first-generation drugs, whereas the ongoing love affair with what is new, marketed as different, and pricey remains unabated. The usage data for clozapine, a medication which has turned around the lives of many people with schizophrenia who did not respond to multiple trials of first- or second-generation antipsychotics, however, remain flat.

In my state government agency, we require our prescribers—more than 700 doctors and nurses who work for the 22 Office of Mental Health–operated hospitals and scores of outpatient clinics (where we often supply medication to uninsured patients)—to engage in a structured critical thinking exercise on antipsychotic medications (a type of checklist for themselves) and to make a case for using the newer, costly medications before they are dispensed (Sederer 2010). We operate on a fixed budget. If we spend millions on drugs that perform less well per dollar spent than comparable medications, then we have fewer dollars to spend on clinical staff and community services. Sometimes it is worth the extra money, but usually, it is not. Some managed-care companies administering mental health services require prior approval for a variety of medications. However, the experience of most prescribers is that “just say no” is often the ethos of these management companies; it generally is not a careful review of the cost benefit by senior medical staff, which is how we do it at my agency.

Our state mental health agency, as well, has made a concerted, multiyear effort to increase the use of clozapine, which is slowly working (Carruthers et al. 2016). About 18% of our patients, who are known to not have typically responded to multiple medication trials or who were on lots of different medications (polypharmacy, which is also not known to work for most patients) are taking clozapine, compared to a statewide average of less than 4% (national figures are also very low). Here again, we see that use of one comparably very affordable drug demonstrates how less money and fewer drugs can do more for patients and thus for their family and community.

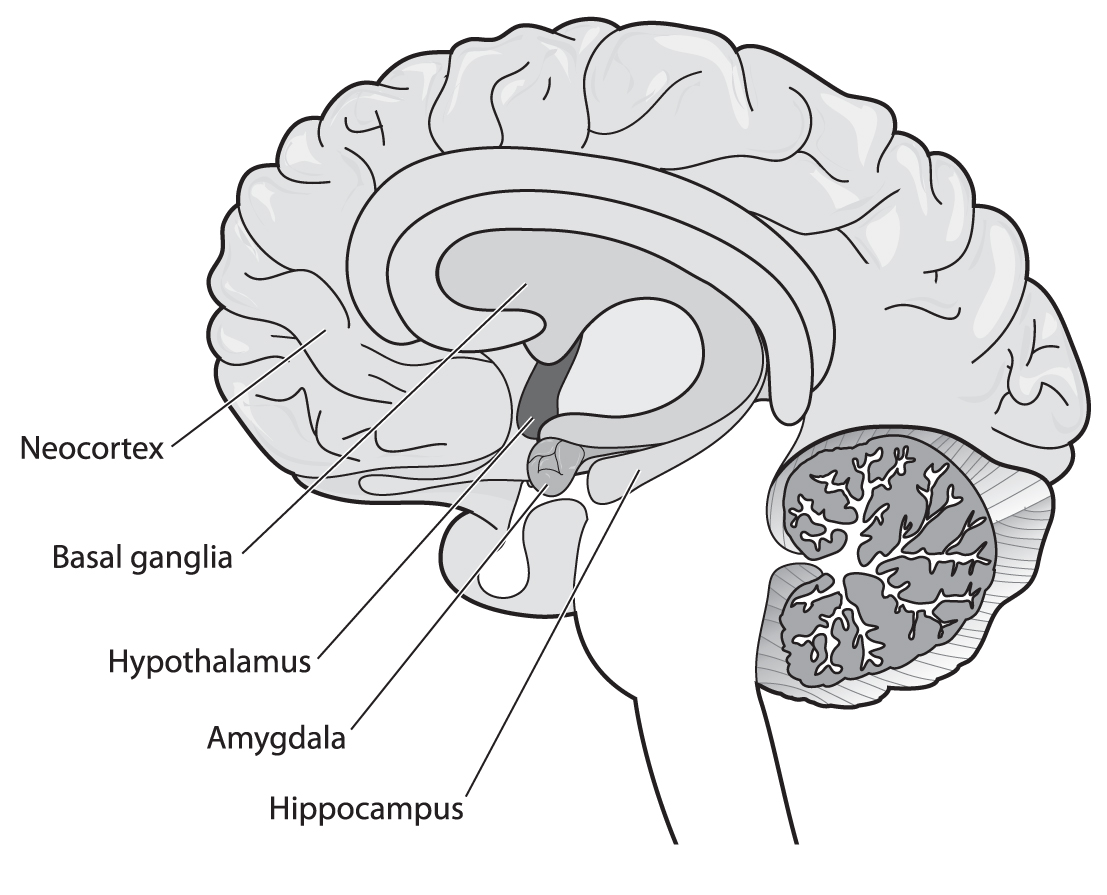

Human hippocampus.

© Blamb. Used under license from Shutterstock.com.

In psychiatry, work is well underway to develop biomarkers (like DNA profiles or enzyme measures) that will better predict which patient will respond to which medication and at what point in their illness. When these biomarkers become part of our arsenal, we will be better able to see that less is more; we will not have to use a “shoot in the dark” methodology. But we are not there yet. Until then, doctors and nurses, administrators, policy gurus, patient and family advocates, and legislators need to support, at times insist on, practice patterns that are informed by evidence that acknowledges that antipsychotics, except for clozapine, manifest relatively equal effectiveness; they need to consider patient histories of response; and they need to examine and act upon cost-effectiveness data so that money can be repurposed to other than medication treatments. When that happens, we will have done more by doing less. That will not only help our patients and their families, it will honor a tradition of integrity in medical care that seems too often quashed by marketing and false promises. That is yet another secret worth spreading in mental health care.

False Memories

In a fascinating set of experiments, scientists at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) were able to prove that mice could form false memories. False memories, convictions of individuals that something occurred that did not actually happen, have bedeviled mental health professionals faced with highly distressed people who assert they were sexually or physically abused in the past, as well as legal professionals faced with witnesses in courtrooms who provide testimony that could potentially convict someone of a heinous crime.

The MIT team focused on the hippocampus, the area of the brain, in mice and men, known to be associated with memory. Memory is established by a complex encoding process that includes both chemical and physical (connectivity) changes involving hippocampal brain cells. The scientists engineered changes in the brains of mice that would allow for a specific blue light to stimulate the hippocampus, thereby producing a protein involved in memory formation and recall. They then conditioned these mice to experience fear by placing them in a chamber, chamber A, where they would receive shocks to their feet. They then placed these mice in another chamber unlike the first, chamber B, where they were again given foot shocks while being exposed to the blue light, thereby conditioning a fear response (seen as freezing in mice) to this specific light color. Finally, the mice were placed in yet another chamber, C. When exposed to blue light in this setting, they demonstrated a fear response of the magnitude seen in chamber A even though they were not shocked in this new and different third setting. A false memory, stimulated by an association with a harmless light to electric shock, had been created in the mice, which had them respond fearfully to a situation that was not a danger to them. The control group did not show the same fearful response. These MIT scientists had shined a light, so to speak, on the neurobiological correlates of the phenomenon of false memory (Ramirez et al. 2013).

Cognitive studies have shown that humans, not just mice, show activity in the hippocampus during both genuine and false memories. Memory is dynamic and subject to many sources of input and alteration. What is going on demonstrates that our minds are not simply like cameras faithfully recording an event. Instead, our brains engage in a process of synthesizing (fabricating) memories from fragments of that event coupled with a myriad of internal associations, imaginings, experiences, and even dreams. This is not conscious or intentional, but it is universal. The result is great variability in the “truthfulness” of a memory: the result is the considerable unreliability of our memories.

When I was the chief medical officer at McLean Hospital outside of Boston, we had a specialty service for people, often women, with trauma disorders, usually not induced by disaster, war, torture, or forced relocation. Rather, they were suffering from dissociative disorders. They would arrive at the hospital by ambulance having done something painful to themselves, like severe cutting or burning or attempting suicide. Many had well-documented histories of physical or sexual abuse. Some of our patients told us that they were traumatized, although there was no medical or legal corroborating evidence, but that the trauma had been “retrieved” in the course of psychotherapy. For our short-term inpatient services, uncovering the cause of a person’s traumatic or dissociative disorder was not the central concern at the time of the hospital stay (except of course if there was imminent external risk, such as domestic violence). Our work was to help the person find a place of psychological safety and calm, establish an effective community aftercare treatment plan, and foster hope for recovery. We rigorously avoided any exploration of past trauma or memories. Instead, our clinicians focused on the here and now and offered techniques and treatments for controlling and mastering intense feelings, fears, and self-destructive behaviors while they also mobilized family and community supports.

While this clinical care was taking place, other colleagues (in particular, Drs. Elizabeth Loftus and Paul McHugh) and other hospitals, such as McLean Hospital and Harvard University–affiliated hospitals, and university centers around the country were investigating what came to be known as false memory syndrome (FMS). FMS is a not uncommon condition in which a person believes with the same conviction as the mouse in chamber C that something happened to them in a particular setting or with a particular person that was egregiously painful and out of their control. The power of the memory disrupts the person’s capacity to live effectively and renders them highly vulnerable to triggers. These triggers may be sensory experiences or incidents, what they feel in their bodies, see on TV, or hear from friends, which ignite a powerful, negative emotional response, which the affected person will do almost anything to avoid. Some individuals may even engage in various forms of self-injurious behavior to temper their psychic distress.

The consequences of false memory recovery do not stop with those experiencing the memories; they also extend to the loved ones and caregivers who are alleged to have perpetrated the abuse. Family members have been accused of abuse, and allegations have been promulgated against doctors and mental health professionals, which have led to court cases against therapists brought by patients claiming iatrogenic (doctor induced) harm. Some of these recovered memories include childhood abuse and even bizarre satanic rituals. Outside of my field, cases have occurred where false memories have prompted allegations of abuse in school and religious settings. Some consider UFO sightings and reports of alien abduction to stem from our ever-present capacity to create fiction from the world around us.

I do not mean to suggest that all recovered memories are false. Surely, some are indeed true. Did you see Doubt? What do you think happened in that fictitious story but very real play and movie?

False memory is especially catastrophic when the (false) memory is of a family member who is believed to have perpetrated the abuse. Families can be shattered, and critical support for a person with genuine serious emotional problems is cut off by the false memory of abuse. The destructive force of false memory is very real. The life of the person who experiences these memories becomes profoundly compromised as they try to manage their distress either by avoidance or by devoting an inordinate amount of time, therapeutic attention, and resources in an attempt to extirpate them.

FMS achieved greater recognition because of clinical researchers investigating recovered memory therapy, a previously popular (and still persistent today) psychotherapy approach that seeks to uncover repressed memories and traumas considered by its proponents to be the genesis of a person’s mental distress and disorganized life. Recovered memory therapy is entirely different from recognizing and acknowledging the tragedy and great prevalence of proven instances of childhood abuse, which is discussed in Chapter 4 (“Chronic Stress Is the Enemy”) among other serious adverse childhood experiences. Adverse childhood experiences cry out not just for early detection and good treatment but also for far greater efforts at prevention. Recovered memory therapy, instead, actively pursues inquiry into a person’s past using the influence of the therapist to suggest that a trauma did occur, when, in fact, it may not have. From what is known about FMS and human suggestibility, this is a type of therapy where more of that treatment is surely less of what the patient needs; a therapy that should be beneficial produces a worsening of symptoms and a life lived encumbered by a fiction generated by a bad, intensive psychotherapy. This seems all too reminiscent of pouring boiling oil on a wound that needs gentle healing.

The medical principle primum non nocere compels us. Less is (far) more when more is unnecessary. Less is (far) more when more gives rise to further psychopathology in people already suffering. People with mental illness do not need to be further burdened by therapists who engender yet another layer of difficulty, an insoluble problem (because it is fabricated) that consequently leaves mice, men, and women with little to do but freeze in place.

Examining ourselves.

© Niels Hariot. Used under license from Shutterstock.com.

It is difficult to write about this secret without appearing critical, with 20/20 hindsight about other people’s excesses and mistakes. I hope that is not how this reads to you. That is not my intent. I, too, am only human and have made more than my fair share of mistakes.

However, it seems to me that to not declare less as more (in general) as one of the more common and consequential lessons in mental health care would be an irresponsible omission, and one meant to protect my profession from what is appropriate and necessary self-examination. The examples I have chosen are by no means comprehensive or necessarily what others might point to. But, they were chosen to illustrate how hard medical and mental health work can be and how sometimes the best of intentions, as has often been said, can pave the way to (therapeutic) hell. Or as my grandmother might have said (if this is not a false memory on my part), be careful because the less said and the less done may prove to be the more prudent of courses to take.

References

Carruthers J, Radigan M, Erlich MD, et al: An initiative to improve clozapine prescribing in New York state. Psychiatr Serv 67(4):369–371, 2016 26725299. Available at: http://ps.psychiatryonline.org/doi/full/10.1176/appi.ps.201500493.

Collins F: Study may RAISE standard for treating first psychotic episode. National Institutes of Health Director’s blog, October 20, 2015. Available at: https://directorsblog.nih.gov/2015/10/20/study-may-raise-standard-for-treating-first-psychotic-episode/. December 28, 2015.

Drake RE, Sederer LI: The adverse effects of intensive treatment of chronic schizophrenia. Compr Psychiatry 27(4):313–326, 1986a 2873959

Drake RE, Sederer LI: Inpatient psychosocial treatment of chronic schizophrenia: negative effects and current guidelines. Hosp Community Psychiatry 37(9):897–901, 1986b 3758971

Lewis DA, Lieberman JA: Catching up on schizophrenia: natural history and neurobiology. Neuron 28(2):325–334, 2000 11144342

Lieberman JA, Stroup TS: The NIMH-CATIE Schizophrenia Study: what did we learn? Am J Psychiatry, 168(8): 770–775, 2011 21813492

Ramirez S, Liu X, Lin PA, et al: Creating a false memory in the hippocampus. Science 341(6144):387–391, 2013 23888038

Sederer LI: Is Your Doctor Using A Checklist? The Huffington Post, February 23, 2010. Available at: http://www.huffingtonpost.com/lloyd-i-sederer-md/is-your-doctor-using-a-ch_b_473068.html. Accessed December 28, 2015.

Swarz MS, Stroup TS, McEvoy JP, et al: What CATIE found: results from the schizophrenia trial. Psychiatr Serv 59(5):500–506, 2008 18451005