Introduction to the Alphabet Oracle

This chapter will introduce you to the Alphabet Oracle. First, you will learn the interesting story of the expedition that discovered it. Next, I will give you a little practical advice on learning the Greek alphabet, in case you don’t know it. (Don’t worry, it’s easy!) Finally, I will say a little about who used the oracle in ancient times and how you can use it now.

Origin of the Alphabet Oracle

Catharine Lorillard Wolfe (1828–1887), heir to the Lorillard Tobacco fortune, art collector, and generous philanthropist, who made significant donations to the Metropolitan Museum of Art, also supported archaeological expeditions. In the summers of 1884 and 1885, she financed the Wolfe Expedition to Asia Minor, led by Dr. J. R. Sitlington Sterrett (1851–1914), a young archaeologist, to locate and record ancient inscriptions.53 The 1885 expedition, which began in May, traveled into the unmapped interior of Turkey on horseback with servants, a cook, tents, and equipment. Mapping along the way, each night they camped near a village (often nothing more than a handful of homes), where they obtained supplies and inquired about inscriptions and other ancient remains in the area.

Many of the archaeological remains were badly damaged; Muslim zealots had destroyed earlier Christian and Pagan buildings and monuments. Many of the stones had been reused to build mosques, fountains, and even private homes; some were used as tombstones. Since the local inhabitants could not read the Greek or Latin inscriptions, they supposed that they showed the way to hidden treasure, and so they were reluctant to reveal inscriptions on the stones used in their homes. Other locals thought that the treasure was hidden inside the stones themselves, so they broke them up.

If Sterrett couldn’t read an inscription due to its position in a wall, he would offer to pay the owner to demolish it. Some stones were partly buried, and Sterrett paid the villagers to dig them up and move them. He reports that sometimes he had to hang upside down in a hole, in the blazing sun, to read an inverted, buried inscription. One time, he had wood brought from several miles away to construct a fifty-foot ladder so that he could totter for two hours on the top rung, a pencil in one hand, a notebook in the other, to copy an inscription off a wall. In another place, he had to jump down into waiting arms from a forty-foot cliff, which he had climbed to copy an inscription. He worked to exhaustion almost every day.

The expedition traveled through wooded country, dry river beds, and mountainous terrain, “for the most part over wild and difficult country,” and on September 2 they arrived in the Sigirlik valley. Following “rough and tortuous” paths, they arrived at an immense, ruined monastery on the side of the mountain. They camped by it and the next morning spent two hours climbing to the summit. There they found the Alphabet Oracle, engraved in the stone wall. They expected to find it there, for August Schönborn (1801–1857) had discovered it in May 1842, but Sterrett was the first to make an accurate copy and publish it (1888).

In 1986—nearly a century later—the archaeologist Johannes Nollé traveled to Turkey to inspect the oracle and make a new copy. Sadly, he discovered that shortly before, a treasure hunter had drilled holes in it with a jackhammer, inserted dynamite sticks, and blown it apart, supposing there was treasure behind. As a result, much of the inscription was destroyed, and the only record we have of some parts is the copy Sterrett made a century earlier.54

We are fortunate that over the years archaeologists have found a dozen tablets, more or less complete, inscribed with Alphabet Oracles. They have been found at locations in Turkey that correspond to the ancient lands of Phrygia, Pisidia, Lycia, and Pamphylia, and also on Cyprus, and date to the second to third centuries CE. Perhaps surprisingly, the text is very similar among them, and so these tablets represent a coherent tradition of ancient divination. Nollé has gathered the most frequent readings into a koinê (Grk., “common”) text, which is the one I have used. In a few cases I have added readings from the Olympos tablet, and if you want to know why, read the next section.55

What About the “Limyran Oracle”?

You might have seen the “Limyran Alphabet Oracle” on the Internet and be wondering how it is related to the Alphabet Oracle presented here. However, if you have not heard of it, I suggest that you go on to the next section, since what I am about to write about it will be irrelevant to you. When I began using the Alphabet Oracle for divination, I used one of the few complete texts available, which was that recorded by the Wolfe Expedition and published in Sterrett’s The Wolfe Expedition to Asia Minor and in Heinevetter’s Würfel- und Buchstabenorakel in Griechenland und Kleinasien. The inscribed oracle tablet was reported to be from the ancient city of Limyra. Therefore, when I did my translation and made it available on the Internet in 1995, I called it “The Limyran Alphabet Oracle.” In this form it has been used successfully by many people and has been widely copied to other sites (with and without permission). I also published it in several magazines (see Bibliography). I have been very pleased that so many people have found it to be a worthwhile divination tool.

In 2004, I learned from Dr. Nollé that there was an error in the original publication and that the pillar was in fact from the ancient city of Olympos in Asia Minor. Therefore, I corrected my website and retitled it “The Greek Alphabet Oracle from Olympos,” and you might know it by that name. As it turns out, the Olympos oracle differs in several ways from most of the other surviving alphabet oracles. Therefore, in this book I have used this more common text, which has been reconstructed by Nollé from the surviving fragments.56 I have not abandoned the Olympos oracle, however, and I provide its text here when it differs from the common text, sometimes with an improved translation compared to my original one. So now you know what has become of the “Limyran Oracle”!

Learning the Greek Alphabet

In order to use the Greek Alphabet Oracle, it helps if you know the Greek alphabet! If you don’t know it, however, don’t worry, because it’s very easy to learn well enough to use the Oracle. It’s certainly easier than learning the runes or ogham. First of all, you will be happy to discover that you already know almost half of it, because the following uppercase Greek letters have approximately the same sounds as the corresponding Roman letters: ABEIKMNOTZ. They have different names from the Roman letters (alpha, beta, etc.), but that’s not so important (you’ll see their names in the tables). Several other letters look like Roman letters, but have different sound values in Ancient Greek. Thus H is called êta and stands for the sound AY (which I write ê in transcribed Greek words). P is called rho and has an R sound (think of P as a one-legged R). X is called chi or khi and has an aspirated (breathy) k sound something like ch in Scottish “loch” or German “acht.” Y is called upsilon and is a “close front rounded vowel” (written /y/ in the International Phonetic Alphabet); it is pronounced like ü in German or like French u in tu or û in sûr.

The remaining letters look different from Roman letters, but you may be familiar with some of them from the Greek letters of sororities or fraternities, from science or math classes, or other common uses. They are:

•  (delta) has a D sound and resembles a D; you might know it as a symbol of change in mathematics or from the emblem for Delta Airlines. Or you can think of the Nile or Mississippi River deltas.

(delta) has a D sound and resembles a D; you might know it as a symbol of change in mathematics or from the emblem for Delta Airlines. Or you can think of the Nile or Mississippi River deltas.

•  (pi) is a P sound, and you probably remember the lowercase

(pi) is a P sound, and you probably remember the lowercase  from math classes.

from math classes.

•  (theta) is a soft TH sound; you might remember it from math, since lowercase

(theta) is a soft TH sound; you might remember it from math, since lowercase  is often used as a symbol for an angle.

is often used as a symbol for an angle.

•  (sigma) is an S sound; it stands for “sum” in mathematics and statistics. Ancient Greeks sometimes wrote it C, which might help you to remember its sound if you think of a soft C.

(sigma) is an S sound; it stands for “sum” in mathematics and statistics. Ancient Greeks sometimes wrote it C, which might help you to remember its sound if you think of a soft C.

•  (lambda) is an L sound, and it looks a little like a rotated L.

(lambda) is an L sound, and it looks a little like a rotated L.

•  (gamma) is a G sound.

(gamma) is a G sound.

•  (xi) is a KS or X sound, which it resembles, but don’t confuse it with khi.

(xi) is a KS or X sound, which it resembles, but don’t confuse it with khi.

•  (phi) has a PH or F sound.

(phi) has a PH or F sound.

•  (psi) sounds PS and is sometimes used as an emblem in connection with psychology, psi phenomena, etc.

(psi) sounds PS and is sometimes used as an emblem in connection with psychology, psi phenomena, etc.

•  (ômega) is a long-O sound; it looks kind of like an O with a line below it. It is the last letter of the classical Greek alphabet, and we sometimes use

(ômega) is a long-O sound; it looks kind of like an O with a line below it. It is the last letter of the classical Greek alphabet, and we sometimes use  and

and  —Alpha and Omega—to mean the beginning and end of anything, and thus its totality.

—Alpha and Omega—to mean the beginning and end of anything, and thus its totality.

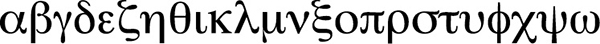

This then is the classical Greek alphabet in the alpha-beta order in which children would have learned it:

You do not need to remember this order if you use the charts in this book. Also, you do not need to know the lowercase Greek letters for the purpose of consulting the Oracle, but here they are:

We Are All Wayfarers

The engraved tablets containing the alphabet oracles were commonly displayed in the market squares or other public places. They seem to have been intended for answering practical questions from people engaged in some enterprise, and typical querents may have been merchants or pilgrims passing through the town. Their activities were fraught with uncertainty. Of course, they were concerned with the success of their plans, but there were other questions. Would they have an accident or get sick? Would they be robbed or murdered? Would they lose their way? Which was the best way to go?

Sometimes the Oracle makes a straightforward prediction, for example, ( ) “All these things, he says, you’ll do quite well.” In these cases, we should understand the oracle to mean that this will be the outcome if current conditions continue. Make a change, and the outcome could be different (for better or worse). In other cases, the prediction is more conditional, for example, (

) “All these things, he says, you’ll do quite well.” In these cases, we should understand the oracle to mean that this will be the outcome if current conditions continue. Make a change, and the outcome could be different (for better or worse). In other cases, the prediction is more conditional, for example, ( ) “In everything, thou shalt excel—with sweat!” In other words, success is conditional on hard work. Yet other oracles state a fact, and you are left to determine what to do about it. For example, (

) “In everything, thou shalt excel—with sweat!” In other words, success is conditional on hard work. Yet other oracles state a fact, and you are left to determine what to do about it. For example, ( ) “Helios, all-watcher, watches thee.” Is he watching over you? Or is he witnessing your crime? Or something else? You are left to decide. In such a case, if after careful consideration it is unclear why the god told you this, it might be advisable to present a follow-up query to the Oracle (but remember the warnings in Chapter 3 about repeating divinations!).

) “Helios, all-watcher, watches thee.” Is he watching over you? Or is he witnessing your crime? Or something else? You are left to decide. In such a case, if after careful consideration it is unclear why the god told you this, it might be advisable to present a follow-up query to the Oracle (but remember the warnings in Chapter 3 about repeating divinations!).

The Alphabet Oracle in the city of Adada in ancient Pisidia (modern Karabaulo, Turkey) had a sort of prologue, from which I’ve adapted the following:

Apollo, Lord, and Hermes, lead the way!

And thou, who wanders, this to thee we say:

Be still; enjoy this oracle’s excellence,

for Phoebos Apollo has given it to us,

this art of divination from our ancestors.57

Although we might not be wandering pilgrims or merchants on business trips, we are all wayfarers on the pilgrimage of life. We have plans, projects, goals, tasks to accomplish, people we want to spend time with, sights to see, and places to go. We also face joys and sorrows, challenges and accomplishments, health and sickness. Even if you never leave your birthplace, you have a long way to go. Therefore, we all can benefit from the advice above as we journey through life: Be still. Consider what you need to know to fulfill your destiny, and ask the gods for guidance. Cast the lots and enjoy the Oracle’s excellence!

53. Information of the Wolfe Expedition is from Sterrett, The Wolfe Expedition to Asia Minor and Leaflets from the Notebook of an Archaeological Traveler in Asia Minor.

54. Nollé, Kleinasiatische Losorakel, 232. Plates 22a and 22b show the vandalized oracle; Plate 21 shows the rough terrain.

55. The texts are collected, edited, compared, classified, and translated into German in Nollé, Kleinasiatische Losorakel, ch. 4; the Koinê text is on pp. 249–250.

56. Nollé, Kleinasiatische Losorakel, 249–250.

57. Heinevetter, Würfel- und Buchstabenorakel in Griechenland und Kleinasien, 33–34.