The American commanders who fought in the Nez Perce Campaign were all veterans of the Civil War and their experience in that conflict shaped their methods of warfare. Each had risen to at least division command during that conflict and demonstrated competence in maneuvering troops in the field. Except for Howard, all had prior experience in the peculiar requirements of Indian fighting. Although General William T. Sherman, commanding general of the US Army, made a number of statements in 1866–69 about exterminating hostile Indian tribes, the commanders who fought the Nez Perce did not believe or practice genocidal methods. Rather, the army leaders who fought the Nez Perce were driven by personal agendas, ranging from desire for promotion to avoiding the appearance of failure.

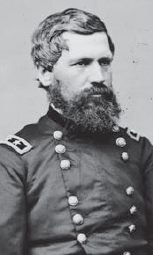

Brigadier-General Oliver Howard, as he appeared during the Civil War. Howard failed to appreciate that the clumsy and firepower-intensive methods of the Civil War were ill suited to Indian warfare and his inability to suppress the Nez Perce uprising quickly encouraged other local tribes to go on the warpath in the following year. (Library of Congress)

Howard had been in command of the Department of the Columbia since July 1874. He was born in Maine and graduated fourth in his class from West Point in 1854. Commissioned as a second lieutenant in the ordnance branch, Howard served in non-troop assignments for the first seven years of his career, including instructing mathematics at West Point. In 1857, he converted to Evangelical Christianity, which had a profound effect upon his later attitudes and his relationship with his fellow soldiers and the Nez Perce. He tended to select and favor officers whom he considered “active Christians” while despising those Indians who rejected Christianity.

At the start of the Civil War, Howard was made a brevet colonel and served as a brigade commander at the battle of First Manassas and during the Peninsula Campaign. At the battle of Fair Oaks on June 1, 1862, Howard was shot twice while leading his brigade, requiring the amputation of his right arm. Over 30 years later, Howard was awarded the Medal of Honor for this action. After a very brief recovery, he returned to the Army of the Potomac and took over the Second Division in II Corps when Major-General John Sedgwick was wounded at the battle of Antietam. At both Antietam and Fredericksburg, Howard led his division in costly and futile frontal assaults that were repulsed. Shortly afterwards, Howard was promoted to major-general and given command of XI Corps. On May 2, 1863, Howard’s corps was routed at the battle of Chancellorsville when struck in a surprise attack by Stonewall Jackson’s forces after Howard had disregarded the enemy’s ability to maneuver through heavily wooded terrain and had failed to take adequate security precautions. On July 1, 1863, Howard’s corps was again routed on the first day of the battle of Gettysburg and suffered 41 percent casualties. Arguably the most important moment in Howard’s military career came when he made the spot decision to anchor the Union “fishhook” defensive position on Cemetery Hill – a position that he successfully defended for the next two days. After Gettysburg, Howard’s corps was transferred west to the Army of the Cumberland and he fought in the battle of Chattanooga. During the Atlanta Campaign, he badly fumbled a flank attack at Pickett’s Mill on May 27, 1864, and then failed to sever the last Confederate-held rail line into Atlanta. Despite this lackluster performance, Howard was given command of the Army of Tennessee in July 1864, which he commanded during Sherman’s March to the Sea and subsequent campaign in the Carolinas. Howard gained considerable experience with handling large formations during the Civil War but his combat record was primarily of failure. Formations under his command tended to achieve little while suffering heavy losses. Combined with this his intolerance to drinking and swearing, Howard inspired little confidence in his troops.

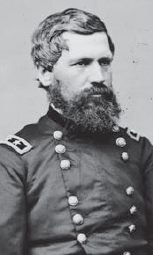

Colonel John Gibbon, commander of the 7th Infantry, succeeded in surprising the Nez Perce at the Big Hole but nearly lost his command in the process. Gibbon was also intimately familiar with the terrain in Yellowstone National Park but he was hors de combat by the time that the Nez Perce reached the park after the battle of the Big Hole. (Library of Congress)

After the war ended, Howard was appointed commissioner of the Freedman’s Bureau, more for his missionary zeal than his organizational talents. Howard spent the next seven years knee-deep in Reconstruction issues but far removed from any military duties. In mid-1872, Howard was sent to Arizona to negotiate with the Chiricahua Apaches and he successfully forged a peace treaty with Cochise. Nevertheless, Howard’s military career might have been over had not the Modoc Indians murdered Major-General Edward Canby, the head of the Department of the Columbia in April 1873. Since the postwar US Army had few other generals lying around unemployed and Howard appeared well suited to the job of reining in the Non-Treaty Nez Perce, he was sent west as a negotiator, not as a combat commander. Howard was a world-class military incompetent, often inclined to lie or shift blame about his failures. There is no doubt that Howard was intelligent and perhaps a bit of an intellectual, but he was not inclined to make decisions quickly or to accept advice easily from others. His style of command was probably best suited to static positional warfare, but he had no head for a war of maneuver. He consistently failed to understand either the terrain or the enemy and drove his long-suffering troops as if they were a pack of mules.

Born in Philadelphia but raised in North Carolina, John Gibbon graduated from West Point in 1847 and was commissioned in the artillery. He saw no combat in the Mexican War but served in Florida against the Seminoles. Just before the Civil War, he was teaching artillery tactics at West Point. During the Civil War, Gibbon was promoted to brigadier-general of volunteers in May 1862 and successfully led the Iron Brigade at Second Manassas, South Mountain and Antietam. At Brawner’s Farm on August 28, 1862, Gibbon’s brigade stubbornly held off a surprise flank attack by Stonewall Jackson’s Corps, despite being outnumbered three to one. Afterwards, Gibbon was elevated to division command and held this role for the next two years through some of the thickest fighting of the Civil War. He spent much of the war serving under the best corps commanders that the Union Army had to offer – John Reynolds and Winfield Hancock. On the third day at Gettysburg, Gibbon’s division helped to defeat Longstreet’s assault, although Gibbon was wounded. Later, he returned to command his division during the battles of the Wilderness, Spotsylvania and Cold Harbor. In January 1865 Major-General Gibbon took command of XXIV Corps, which he led successfully during the Petersburg and Appomattox campaigns. By the end of the war, Gibbon had gained an immense amount of combat experience and had repeatedly demonstrated battlefield competence.

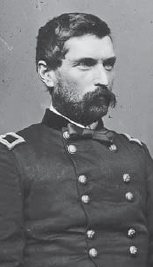

Colonel Samuel D. Sturgis, commander of the 7th Cavalry. Sturgis was brilliantly outmaneuvered at Clark’s Fork Canyon and then tried to atone by riding his cavalry until a third of his horses died, leaving his command immobilized. (Library of Congress)

Reverting to colonel in the regular army after the war, Gibbon helped to explore Yellowstone National Park. During the Sioux Campaign of 1876, he led the Montana column and was the first to reach Major Reno’s surviving remnants of the 7th Cavalry. At the start of the Nez Perce War in June 1877, Gibbon was commander of Fort Ellis near Bozeman, Montana and responsible for the western part of the territory. Gibbon was tough, experienced and aggressive but he was handicapped by inadequate resources and must have resented serving under a less capable senior officer, such as Howard.

Commander of the 7th Cavalry since May 1869. Sturgis was born in Pennsylvania and graduated from West Point in 1846, where he was commissioned in the dragoons. Just prior to the battle of Buena Vista in February 1847, Sturgis was captured by the Mexicans while on a reconnaissance patrol, but was released after barely a week in captivity. After the Mexican War, Sturgis earned his spurs with the 1st US Dragoons, fighting the Apaches in Texas and New Mexico. In January 1855, Lieutenant Sturgis tracked down and defeated a raiding party of Mescalero Apaches after a 175-mile (280km) pursuit. In 1860, Sturgis successfully intercepted a Kiowa raiding group in Kansas.

Although he was only a captain at the start of the Civil War, Sturgis was an experienced cavalry officer and he was promoted to major and given a brigade in Brigadier-General Nathaniel Lyon’s Army of the West. When Lyon was killed at the battle of Wilson’s Creek in Missouri on August 10, 1861, Sturgis took command at a critical moment and conducted an orderly withdrawal. Having demonstrated battlefield competence, Sturgis was appointed brigadier-general of volunteers in 1862 and given command of the 2nd Division, IX Corps. He performed well at South Mountain and his division captured Burnside’s Bridge at the battle of Antietam, but at Fredericksburg his division suffered 21 percent casualties in the futile assault upon Marye’s Heights. After Fredericksburg, Sturgis was relieved of command and sent to Tennessee for occupation duties. In June 1864, Sherman ordered him to deal with Major-General Nathan Bedford Forrest’s cavalry raids on Union lines of communication but Forrest decisively defeated Sturgis at the battle of Brice’s Crossroads. Despite a five-to-two numerical superiority, Sturgis’s command was smashed and Forrest captured 1,500 of his men and 16 guns. Sturgis was relieved again.

After the Civil War ended, Sturgis reverted to the rank of lieutenant-colonel in the regular army and was given command of the 7th Cavalry. He missed the Sioux campaign of 1876 but his son was killed with Custer’s battalion at Little Bighorn. Sturgis was a very experienced cavalryman and Indian fighter, but no longer had the self-confidence required for independent command.

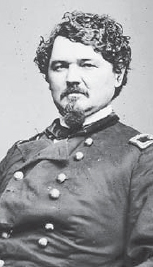

Unlike the other army commanders in the Nez Perce War, Miles had not attended West Point. Instead, he was a self-taught civilian with an enthusiasm for military affairs who was working as a clerk in his uncle’s store in Boston at the start of the Civil War. Miles managed to borrow $3,000, which he used to organize a company for the 22nd Massachusetts Volunteers and he was appointed as a second lieutenant. In November 1861, Miles was assigned as aide to Oliver Howard and served under him in the Peninsula campaign. When Howard was wounded at Seven Pines, Miles held the shattered arm as it was being amputated.

Colonel Nelson “Bear Coat” Miles, commander of the 5th Infantry in 1877 and one of the most dynamic soldiers in the US Army of the mid-19th century. He was a self-made man and blatantly ambitious, which caused friction with his less-capable peers and superiors, but nobody was better at running hostile Indian groups to ground than Miles. His aggressive use of infantry in winter campaigning over rough terrain set a standard that has never been bettered by other American troops. Miles’s victory at Bear Paw salvaged the reputation of the US Army in an otherwise mismanaged campaign. (Author’s collection)

Miles was intensely ambitious and he was able to gain promotion and command of the 61st New York Volunteers, which he ably led at Antietam, Fredericksburg and Chancellorsville. Miles was badly wounded at the last action, for which he was awarded the Medal of Honor and gained the admiration of his corps commander, Winfield Hancock. Although his recovery was slow, Miles was given command of a division under Hancock in 1863 and he demonstrated innate aggressiveness in fierce attacks at Spotsylvania Court House, Cold Harbor and Petersburg. Thanks to his superb battlefield performance and the support of senior officers such as Howard and Hancock, Miles was breveted a brigadier at age 26 and ended the war as a major-general of volunteers.

After the Civil War, Miles was given command of Fort Monroe and served as jailor of Jefferson Davis, the former Confederate President. He also managed to finesse the rank of colonel in the regular army and married the niece of General William T. Sherman. He spent two years in North Carolina on Reconstruction duty, working closely with Howard’s Freedman’s Bureau, then was sent west to take over the 5th Infantry in 1869. Miles successfully led a column against the Comanches and Kiowas in the Red River War of 1874 in Texas and Oklahoma. He was a close friend of George Custer and after the Little Bighorn defeat in June 1876, Miles led 400 infantrymen of the 5th Infantry in a series of grueling winter campaigns that harried Sitting Bull into Canada and defeated Crazy Horse at the battle of Wolf Mountains in January 1877. Unlike other officers, Miles did not go into winter quarters but continued to chip away at the hostile tribes, even in sub-zero weather, which earned him the sobriquet “bear coat” for his thick fur garments. Although something of a martinet with his 5th Infantry, Miles was respected by his troops since he insured that they were properly equipped for winter campaigning. Like most army officers of the period, Miles viewed most Indians in negative terms but respected their fighting abilities, commenting that, “the art of war among the white people is called strategy or tactics; when practiced by the Indians it is called treachery.”

At the beginning of the Nez Perce Campaign, Miles was in the Tongue River Cantonment in eastern Montana, conducting mop-up operations against the Cheyenne. Miles looked forward to a new campaign as an opportunity to gain promotion to brigadier-general in the regulars. His relationship with Howard was excellent at the start of the campaign but later soured after Bear Paw Mountain. Nelson Miles was probably one of the most energetic, aggressive and experienced brigade-level commanders in the US Army of 1877 and one of the few who had the skill to conduct the kind of high-intensity maneuver warfare that could grind down Indian tribes’ ability to remain at large.

As the Non-Treaty Nez Perce were a loose association of five independent bands, they did not have a fixed or unified leadership structure, beyond the basic fact that each faction had a chief. In the Nez Perce, leaders led by consensus rather than diktat. Unlike their opponents, military authority within the Nez Perce was dispersed and non-hierarchical; warriors followed those men they respected and this could change from day to day. One of the great misconceptions about the Nez Perce campaign is that Chief Joseph was a military leader and that he was in charge of all the factions. In fact, he spoke only for his own Wallowa band and he delegated battlefield leadership to his younger, more aggressive brother Ollokot.

Looking Glass, leader of the Alpowai band and perhaps the most influential of the Nez Perce war chiefs. Although a gifted tactician, Looking Glass’s failure to understand the ‘big picture’ led to catastrophic losses at the Big Hole and Bear Paw. (Author’s collection)

The 45-year-old leader of the Alpowai bands, who lived along the Clearwater River. He made a number of trips to Montana on Buffalo hunts and made friends with the local Crow tribe. In 1874, he fought with the Crows against the Sioux along the Yellowstone River and won great prestige. At the beginning of the war, Looking Glass and his band were already located on reservation land in compliance with Howard’s ultimatum. Even though Looking Glass tried to dissociate his band from the murders caused by White Bird’s band, his group was attacked nonetheless because they were perceived as sympathetic to the hostiles. Looking Glass was in the prime of his life as a warrior and well respected throughout the five factions. He exerted considerable influence both on the overall course of action chosen by the Non-Treaty factions as well as their battlefield tactics, but his authority was never absolute and was actively challenged after he was proven wrong about the supposed sanctuary at the Big Hole. Based upon his prewar experience in Montana, Looking Glass believed that the best option was to seek help with his friends in the Crow tribe, but this also proved illusory. Finally accepting Canada as the only remaining hope, it was Looking Glass who made the fateful decision to rest at Bear Paw rather than push on directly to the border.

Ollokot (center) and two other Nez Perce photographed shortly before the outbreak of war. Ollokot was Joseph’s younger brother and war leader of the Wallowa band’s 55 warriors. It was Ollokot’s ultimatum to the American settlers in the Wallowa Valley that set in motion the events that led to the outbreak of war. (Library of Congress)

Joseph’s younger brother and the primary battlefield leader of the Wallowa band, Ollokot had helped to incite the crisis in the Wallowa Valley in the summer of 1876 that eventually led to Howard’s ultimatum and he appears to have been more hotheaded than his older brother. On the battlefield, Ollokot was a bold and tough opponent, but apparently lacked the experience to take a larger role in directing the movements of the tribe as a whole. He proved adept at mounted attacks both at White Bird Canyon and Camas Meadows and also played a major role in rearguard actions to delay Howard’s pursuit.

Chief of the Wallowa band of the Nez Perce. Despite his postwar fame, Joseph did not play a major role in tactical operations during the Nez Perce campaign and served more in administrative and diplomatic roles; it was Joseph who attended to the myriad needs of over 700 people involved in a 1,100-mile (1,770km) march. Initially, Joseph commanded considerable respect among all five Non-Treaty factions and his proposals to seek sanctuary at White Bird Canyon and then evade Howard’s pursuit were generally accepted. However unlike most of the other faction leaders, who realized after the battle of White Bird Canyon that they must flee Idaho, Joseph held out for returning to the Wallowa Valley as soon as possible. It was only after crossing into Montana that Joseph began to realize that there was no going back and his opinions carried less weight than those proposing escape to Canada. After defeat at Bear Paw, Joseph spent the rest of his life telling the American press how his people had been wronged, while glossing over the fact that they had started the war and murdered dozens of American civilians.

Joseph, Chief of the Wallowa band in 1877. For over a century, Joseph has been mistakenly labeled as the military leader of the entire Non-Treaty Nez Perce faction and as the “Red Napoleon” by an ignorant Eastern press establishment. In fact, Joseph was more of a steward, attending to the daily needs of a people in flight and left battlefield command to others. Postwar accounts inflated Joseph’s role since most of the actual war chiefs were either dead or in Canada and he became lionized as a “hero,” rather than a delusional nonconformist who led his people to defeat and exile. (Author’s collection)

Leader of the Lamátta band of the Nez Perce. Like the other Non-Treaty faction leaders, White Bird adhered to the Dreamer movement and adopted hard-line, traditionalist attitudes. Of all the Nez Perce leaders, he was the most hostile to Americans and notions of mutual coexistence. It was members of his group who played a leading role in the incidents that led to the outbreak of war. Initially, White Bird was the senior war chief of the Non-Treaty factions, but gradually lost his authority to Looking Glass, who was a better tactician. After the battle of Bear Paw, White Bird evaded Miles’s troops and escaped to Canada with some of his band. He lived in Alberta for the next 15 years until one of his followers, angry about their poor living conditions, murdered him with an axe.

Leader of one of the Pikunan band that lived along the Snake River. Toohoolhoolzote was adamantly opposed to moving onto the reservation or abandoning his Dreamer ways in favor of farming. He played a major, if pugnacious role, in prewar negotiations and his arrest by Howard contributed to the breakdown in relations. Indeed, Toohoolhoolzote’s anti-Christian remarks brought out the worst in Howard. Although over 50, Toohoolhoolzote was an active war chief and played a major role in the battle of the Clearwater. He was caught in the open by US cavalry at the battle of Bear Paw and killed.

Chief of the small Palouse band, which was the only other Indian faction allied with the Non-Treaty Nez Perce. Hahtalekin and his son were both killed at the Big Hole.

A half-breed Nez Perce, part French, who became de facto trail leader of the Non-Treaty factions in the Bitterroot Valley of Montana and then through the Yellowstone National Park. Poker Joe was in Montana at the start of the war and he joined the Non-Treaty factions just before the Big Hole. His local knowledge was invaluable during the period from the Big Hole to the crossing of the Yellowstone but after that, he yielded to Looking Glass’s leadership. At the battle of Bear Paw, he was mistaken for a Cheyenne scout and accidently shot by a fellow Nez Perce.