War is the remedy our enemies have chosen, and I say give them all they want. General William T. Sherman, 1862

Joseph and a number of other clan chiefs claim to have been absent from the Tolo Lake encampment while their people were going on the warpath – which may have simply been a means of distancing themselves from later accusations of criminal involvement – but when they returned they were faced with dealing with the consequences of mass murder committed by the Nez Perce. Looking Glass was furious and said, “You have acted like fools in murdering white men” and then immediately took his band back to their land on the reservation. Yet the remaining chiefs realized that war was now imminent, so Joseph and White Bird decided to head south 10 miles (16km) to White Bird Canyon, which was more easily defensible. The outbreak of violence had caused further division within the Nez Perce, between those who tried to dissociate themselves from the murders and those who were too guilty to avoid punishment. Apparently it never occurred to Joseph or White Bird to tell Shore Crossing and Yellow Bull to vanish into the mountains while the rest of the Non-Treaty factions moved immediately onto the reservation, which might have avoided open warfare. Instead, they elected to protect the murderers and everything that followed was a result of the deliberate Nez Perce effort to shield a handful of their tribe from criminal prosecution.

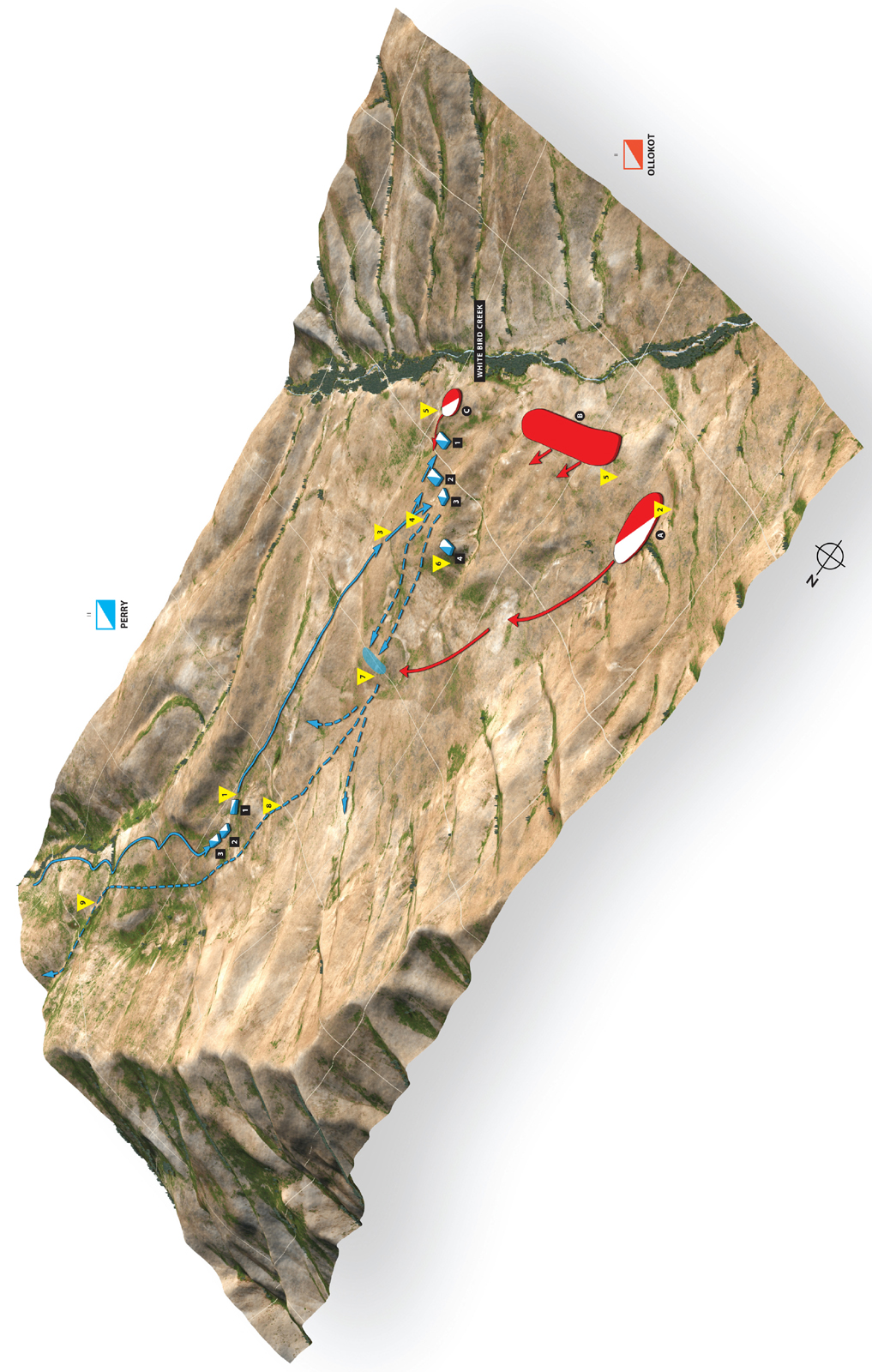

Looking southward down the valley toward the Nez Perce village at White Bird Canyon. Perry’s command approached along this route in the predawn darkness. (Author’s collection)

Colonel Nelson Miles and his staff at the Tongue River Cantonment during the winter of 1876–77. Miles’s winter campaign against the Sioux and other plains tribes just months before the outbreak of the Nez Perce War provided him and his troops with invaluable experience in Indian fighting. (Author’s collection)

At Fort Lapwai, Howard first received word of the attacks on the afternoon of June 15 and immediately dispatched two cavalry companies under Captain David L. Perry to protect the 100 civilians around Grangeville and Mount Idaho. Howard was not certain of the extent of the outbreak and limited his initial call for reinforcements to recalling two other companies of the 1st Cavalry from the Wallowa Valley and three companies of the 21st Infantry from Fort Walla Walla. He was reluctant to call for outside help – which could reflect badly on his handling of the situation – until Perry provided more information about Nez Perce intentions. After a trek of 50 miles (80km) down the Lewiston–Mount Idaho Road, Perry arrived at Grangeville around 2000hrs on June 16. Although his orders were only to protect the town, the civilians were angry about the Nez Perce attacks and demanded that Perry take some punitive measures against them. At this point, Perry demonstrated a serious deficiency in leadership and allowed the civilians in Grangeville to dictate his course of action to him. Without resting his troops, Perry headed south 17 miles (27km) toward White Bird Canyon, along with a small group of armed civilian volunteers.

Perry arrived at the entrance to White Bird Canyon around 0400hrs on the morning of June 17. His command consisted of 103 cavalrymen, three friendly Nez Perce scouts and 11 armed civilian volunteers. Based upon general knowledge from the civilians that the Nez Perce were encamped along White Bird Creek, Perry conducted a movement to contact without any fixed plan regarding what he intended to do once he found the hostiles. He had no orders from Howard to engage the Nez Perce or to negotiate with them. Nevertheless, he headed southward with his own Company F in the lead, followed by Captain Joel Trimble’s Company H, toward two prominent rises with a saddle depression in between. An advance detachment, led by First Lieutenant Edward Theller, scouted about 200 yards (180m) ahead of the main body. By this point, the troops had been in the saddle for hours, having gone two nights without sleep and the rugged terrain they were moving over was tiring to both man and horse, which meant that Perry’s weary command went into action in an exhausted condition. On the approach march, one of the soldiers foolishly lit his pipe, which was spotted by a Nez Perce scout. Perry had no real plan of action and Sergeant Michael McCarthy later said, “If there was any plan of attack, I never heard of it.”

Thanks to the faulty light discipline of the 1st Cavalry troopers, the Nez Perce were now aware that soldiers were coming and they deployed two groups of warriors to protect the most likely avenues of approach. Ollokot led the larger group of about 50 warriors, some mounted and some dismounted, guarding the west side of the valley. A smaller group of 15 warriors under Two Moon screened the eastern side of the village. Nez Perce sources admit that a large number of warriors were still drunk or hung-over after the week of carousing and were unable to take part in the coming battle, so the total number of warriors available was fewer than 100. Joseph, who played only a small role in the battle, dispatched a six-man mounted patrol toward the approaching soldiers – either to parley or to get more information on the threat. The Nez Perce were confident, well rested and operating on familiar terrain, which gave them a number of advantages over Perry’s men.

The twin hills overlooking the Nez Perce village. Perry’s command inclined toward the left hill, while Ollokot’s mounted warriors were deployed toward the right. (Author’s collection)

The view atop the left hill where Perry’s Company F formed a skirmish line. The Nez Perce village was down in the trees below, along the river. (Author’s collection)

The Nez Perce rout the 1st Cavalry.

|

EVENTS |

1 0400hrs: Captain Perry’s column descends into the valley heading toward White Bird Canyon, with Company F leading and Company H in the rear. Lieutenant Theller leads a small advance party and the civilian volunteers about 200 yards (180m) ahead of the main body.

2 0500hrs: Nez Perce scouts detect the approaching cavalry and two groups of warriors are hastily formed to defend the village. Ollokot takes 50 warriors to defend the western approach to the village while Two Moon has a smaller group of 15 to defend the eastern approaches.

3 0615hrs: as they approach the crest, Theller spots the Indian pony herd, but not the village. Shortly afterwards, the civilian volunteers open fire on five mounted Nez Perce approaching to parley.

4 0630hrs: Perry deploys his command on line along the crest of the ridge, with Company F forming a dismounted skirmish line in the center.

5 The civilian volunteers rush toward White Bird Creek but run straight into an ambush by Two Moon’s warriors. After suffering a few casualties, the volunteers retreat in disorder and Two Moon’s group occupies their vacated knoll and pours enfilade fire into Perry’s left flank. Meanwhile, Ollokot begins an encircling movement against Perry’s right flank and warriors in the village begin joining the action.

6 0700hrs: both companies begin to fall back without orders and Perry’s left collapses in a panic. In desperation, Sergeant McCarthy is sent with six troops to hold a piece of rocky high ground on Perry’s right to delay Ollokot’s pursuit.

7 Perry tries to re-form a line at the next piece of high ground to the north, but Ollokot’s warriors quickly disperse the troopers. Perry’s command scatters in headlong retreat.

8 Ollokot mounts a vigorous pursuit and chases the fragments of Perry’s command for more than 5 miles (8km). Wounded cavalrymen are abandoned and killed by the Nez Perce.

9 About 0800hrs: during the retreat, Lieutenant Theller leads a group of seven troops into a steep ravine, where they are trapped and killed in a desperate last stand.

US ARMY

1 Lieutenant Theller’s advance detachment and civilian volunteers

2 Company F, 1st Cavalry (Perry)

3 Company H, 1st Cavalry (Trimble)

4 Sergeant McCarthy’s squad

NEZ PERCE

A Ollokot’s group (50 warriors)

B Two Moon’s Group (15 warriors)

C Warriors under White Bird (30–40 warriors)

Note: Gridlines are shown at intervals of 1km/0.62miles

The view of the cavalry’s position from the Nez Perce position. The civilian volunteers were driven off the cone-shaped hill early in the battle, which allowed the Nez Perce to enfilade Perry’s skirmish line. (Author’s collection)

The view from McCarthy’s Point looking toward the Nez Perce village. Sergeant McCarthy was posted here with six soldiers, but was unable to stop Ollokot’s envelopment from the right. (Author’s collection)

At about 0615hrs, Lt. Theller and his scouts approached the crest of the easternmost ridge and spotted part of the Nez Perce pony herd but not the village, which was hidden by intervening terrain. The mounted Nez Perce group spotted Theller’s scouts and rode toward them but one of the attached civilian volunteers, Arthur Chapman, fired on them. Modern Nez Perce cite this incident to claim that Americans fired the first shot in the war, conveniently ignoring their own murder of 18 American citizens within the previous four days. Furthermore, Perry’s troops had no reason to believe that the Nez Perce were anything but hostile after the death of these civilians, so firing on the supposed parley group was not as unjustified as has been claimed. Rather than blaming Perry for starting a war that ipso facto had already begun, he should be judged harshly for rushing into battle with tired troops and no tactical plan.

Sergeant Michael McCarthy, the senior NCO in Company H, 1st Cavalry, at the battle of White Bird Canyon. The 32-year-old Newfoundland-born sergeant was left to conduct a hopeless rearguard as Perry’s command disintegrated and he was the only survivor of his squad. Cut off and abandoned, McCarthy succeeded in rejoining his unit at Grangeville two days later, for which he was awarded the Medal of Honor in 1897. (Author’s collection)

Hearing the shots fired, Perry immediately rushed the main body forward and began deploying Company F in a dismounted skirmish line along the crest of the ridge. Captain Trimble’s Company H began to occupy the right of Perry’s line but was still mounted when the action began in earnest. There was also a gap of almost 200 yards (180m) between the two companies, which made it difficult for Perry to control his force. Below them, the Nez Perce village was still hidden behind a series of conical-shaped hills, so Perry’s troops could only engage the small groups of Nez Perce warriors who were rushing toward the sound of firing. Perry proved a poor tactician, engaging a foe with the rising sun in his eyes while his own men were silhouetted against the crest of the ridge. He also deployed his skirmish line in open terrain, while ignoring a rock outcropping just 30 yards (27m) to his rear that would have provided excellent cover.

Meanwhile, several of the civilian volunteers rashly chased after the retreating parley group but ran straight into an ambush by Two Moon’s warriors. After taking a few casualties, the volunteers retreated in disorder and Two Moon’s group moved forward to occupy a raised knoll on Perry’s left flank. From this knoll, the Nez Perce sharpshooters poured a deadly enfilade fire into the flank of Company F, killing seven soldiers in the opening moments of the action. Perry’s men could barely see Two Moon’s warriors, who were firing from dead space and concealed by waist-high grass. With both companies on line, Perry’s troops fired several ragged volleys toward their front, while virtually ignoring the threat on their flank. When Perry’s trumpeter was killed by a lucky hit, he lost any remaining ability to influence the troops who were more than a few yards from him. Shore Crossing and his friend Red Moccasin Tops, the two responsible for the initial murders that started the war, were part of Two Moon’s group and they wore full-length red blanket coats intended to show their contempt for the soldiers.

While Two Moon was disrupting Perry’s left flank, Ollokot’s mounted warriors began a wide enveloping sweep around the right flank, out of range of Company H’s carbines. Some warriors were also joining from the village, which kept Perry’s attention focused to his front. After less than 30 minutes of combat, Perry’s command began to disintegrate as more troops were hit by the accurate Nez Perce fire and the realization dawned that they were about to be encircled. The panic began with a few troops on the left falling back without orders but, as the skirmish line dwindled, it was soon every man for himself. The flat area behind the ridgeline was devoid of any cover and the fleeing troops were easy prey for the on-rushing mounted warriors. In desperation, Capt. Trimble sent Sgt. Michael McCarthy and six troopers to hold a piece of rocky high ground on Perry’s right to delay Ollokot’s pursuit while the rest of the command skedaddled back 200 yards (180m) to the next hill mass. McCarthy’s detachment sniped at Ollokot’s warriors and managed to wound one or two of them, which succeeded in delaying the Nez Perce pursuit for a few vital moments. However, once McCarthy and his men tried to retreat across the open ground to rejoin their fleeing comrades, Ollokot’s mounted warriors killed every soldier but McCarthy, who succeeded in evading them.

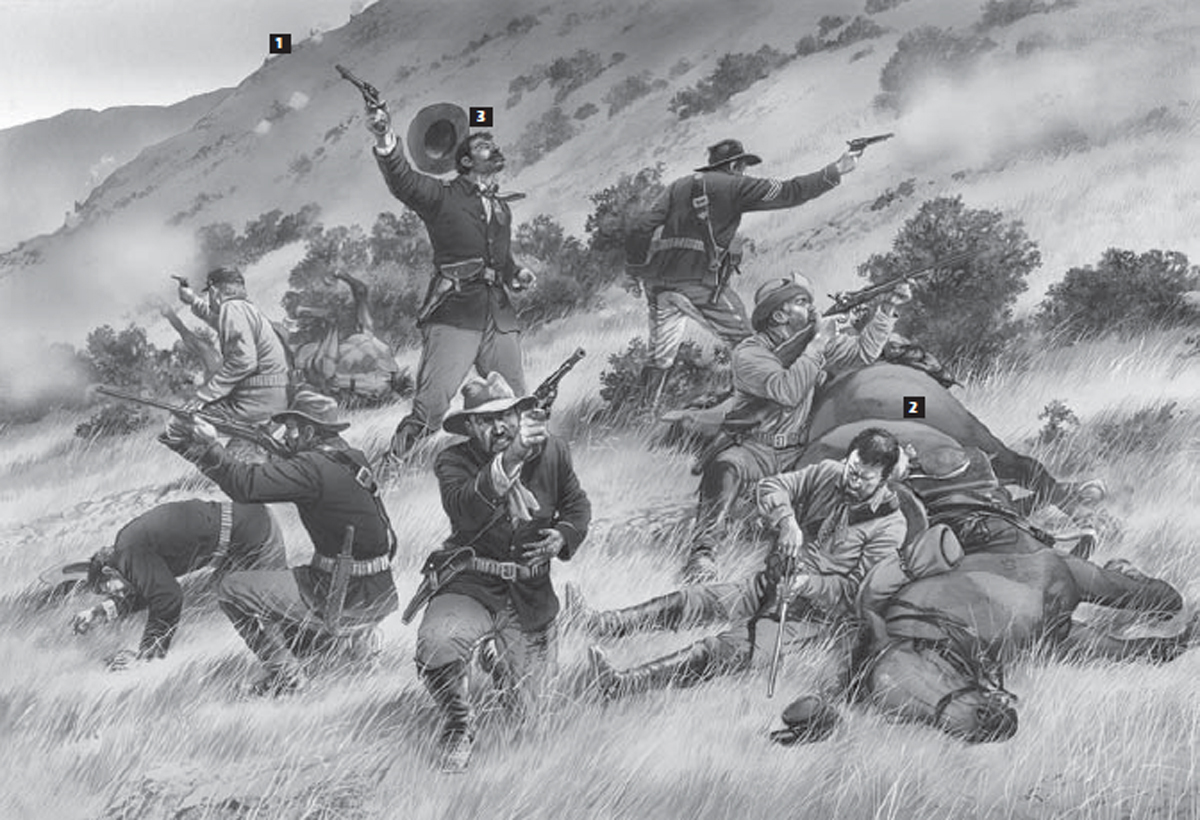

LIEUTENANT THELLER’S LAST STAND, JUNE 17, 1877 (pp. 38-39)

The movement to contact by two troops of the 1st US Cavalry under Captain Perry to the Nez Perce camp at White Bird Canyon quickly resulted in an unexpectedly fierce engagement, followed by a precipitous rout. The troopers of Companies F and H fell back in small groups, pursued by mounted Nez Perce warriors. Quite quickly, the cavalry troops lost all cohesion and it was virtually every man for himself. First Lieutenant Edward R. Theller (1831–77), on loan from the 21st Infantry, had been given command of a squad-sized formation that acted as an advanced guard for Perry’s command as it advanced to White Bird Canyon, but which now found itself abandoned in the headlong retreat. Fleeing up the valley in the wake of their routed comrades, Theller led a group of seven cavalrymen into a dead-end ravine and before they could escape, they were surrounded by a larger group of Nez Perce warriors (1). Lieutenant Theller’s men formed a small perimeter at the bottom of the ravine and hoped for rescue, but Capt. Perry was unaware that Theller’s group had become isolated. Theller’s men fought back hard, keeping the Nez Perce at bay for a while, until their carbine ammunition was expended. Constant Nez Perce fire from above wounded several of the soldiers and most of their horses (2), effectively ending all hope of escape. Once the soldiers reverted to their shorter-range Colt pistols, the Nez Perce warriors gradually closed in and Lt. Theller was killed by a bullet to his brain from an enemy marksman (3). The last soldiers continued firing until all were hit by Nez Perce fire. The Nez Perce then closed in and finished off the wounded. Despite the image of victims that Nez Perce spokesmen have promoted since their defeat, Nez Perce warriors were quite vicious on the battlefield and rarely took prisoners. Most of the dead were also mutilated.

Perry tried to re-form a line at the next piece of high ground to the north, but Ollokot’s warriors pressed them hard and quickly dispersed the troopers. After that, Perry’s command scattered in headlong retreat and all cohesion was lost. Ollokot’s pursuit was vigorous, brutal and effective, hounding the fragments of Perry’s command for more than 5 miles (8km). Wounded cavalrymen who could not flee were killed by Ollokot’s warriors and some of the bodies were mutilated. Sergeant Patrick Gunn of Company F was later found with his severed genitals stuffed in his mouth, the apparent victim of torture. In one of the final actions, Lt. Theller and seven soldiers retreated into a steep ravine where they were soon pinned down by Nez Perce fire from above. After a desperate last stand, all eight cavalrymen were killed. No prisoners were taken. Perry’s survivors huddled in Grangeville for a week, adding scant comfort to the worried civilians.

The battle of White Bird Canyon was a tactical triumph for the Nez Perce. In less than an hour, they had routed two cavalry companies and killed 34 soldiers, while suffering only three lightly wounded themselves. However, any possibility for negotiating with Howard was now gone and the Nez Perce leaders realized that they would soon face a full-scale military campaign against themselves, a war which they could hardly expect to win. Back at Fort Lapwai, the defeated Perry blamed the defeat on the collapse of the civilian volunteers but this was merely an excuse, since his right flank was unable to prevent Ollokot’s encirclement. Indeed, it is probably fortuitous that Perry’s command routed when it did because otherwise it would have been pinned and annihilated by Ollokot’s maneuver. Furthermore, Perry exaggerated the numbers of Nez Perce warriors engaged and omitted the fact that his own troops had enjoyed a five-to-one numerical advantage in the opening moments of the battle.

When two of Perry’s routed troops arrived back at Fort Lapwai, Howard was shocked both by the amount of casualties and the ferocity of Nez Perce resistance. Clearly he was not dealing with a few hotheads, but an armed and unpredictable opponent. As department commander, Howard immediately ordered more companies of the 1st Cavalry, the 21st Infantry and the 4th Artillery to assemble at Fort Lapwai, although it would take weeks for most to arrive. By June 22, he had amassed a mixed force of 227 troops and he decided to take to the field before most of his reinforcements arrived in order to forestall being replaced by a more experienced Indian fighter, such as Brigadier-General George Crook. He deliberately ordered Colonel Alfred Sully, the highly experienced commander of the 21st Infantry, to stay behind and guard Lewiston while taking six of his companies. Howard headed southward from Fort Lapwai with his small command, but with only a small pack train and his logistic preparations soon proved inadequate.

The ravine where First Lieutenant Edward R. Theller and his ten soldiers were wiped out during the retreat from White Bird Canyon. (Author’s collection)

After rendezvousing with Perry at Grangeville on June 25, Howard’s force approached the entrance to White Bird Canyon in pouring rain on the afternoon of June 27. The bodies of Perry’s dead troops were found and buried, but in the ten days since the battle the Nez Perce had slipped unhindered to the west side of the Salmon River and established a new camp at Deer Creek. Howard was now on the wrong side of the river and he fumbled about for the next two days, uncertain what to do. Four dismounted companies of the 4th Artillery and another infantry company joined his command while he bivouacked on the White Bird Canyon battlefield, but Howard still had barely 400 troops and he was uncertain about Nez Perce intentions. Ollokot sent some of his warriors to the west side of the Salmon River to skirmish with Howard’s pickets and to taunt them to try and cross. However, the soldiers only succeeded in fatally shooting one of their own pickets by accident in the dark. Many of Howard’s soldiers were spooked sleeping on the site of Perry’s defeat and expected a Nez Perce attack at any moment, so no fires were lit at night. Furthermore, Howard had rushed from Fort Lapwai so quickly that the troops were forced to sleep out in the mud and rain without tents or blankets. Any army sitting on their hands in drenching rain within sight of a confident enemy and subsisting on cold food is likely to suffer from low morale, which quickly undermined the effectiveness of Howard’s troops. Meanwhile, the Nez Perce warriors could return to their warm lodges for ample food and rest.

On June 30, after nearly three days of inactivity, Howard finally gathered up the gumption to move to the bank of the Salmon River but rather than attempting a crossing at the narrowest and easiest point near the junction with White Bird Creek, he made the ridiculous decision to move north 1½ miles (2km) and cross at some rapids. Throughout the campaign, Howard consistently acted like topography did not exist and his maneuver required the troops to cross a steep, 3,300ft-high (1,000m) ridgeline with wagons, mules and artillery. What should have taken less than a day – crossing a 330ft-wide (100m) river – took three days because Howard would not attempt it until he had artillery support on hand, so the crossing was not completed until July 2. With the troops thoroughly exhausted, Howard then advanced south toward Deer Creek but found the Nez Perce were long gone. The three-day river crossing had given the Nez Perce ample time to pack up their camp and head to the northwest, away from Howard. In just 36 hours, the Nez Perce marched 25 miles (40km) across the mountains and re-crossed the Salmon River at Craig’s Ferry. The Nez Perce conducted this retreat with women and children, along with about 3,000 head of horse. Foolishly, Howard had not even sent scouts across the river to maintain contact with the enemy, so once he crossed he realized that he had no idea where they were.

Caught in a circle by Charles Schreyvogel. The last stands of lieutenants Theller and Rains were similar, with small groups of isolated cavalrymen holding off circling Indians until their ammunition ran out. By the time that the warriors closed in to finish them off, most of the soldiers were wounded. (Library of Congress)

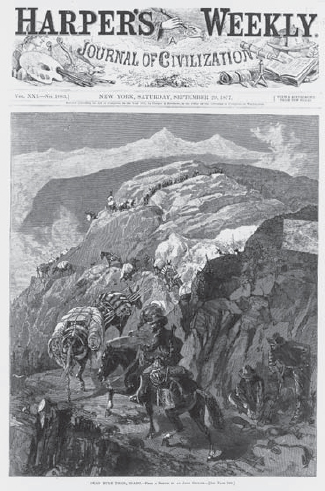

Howard had lost contact with the enemy and he thought they might have split up, with some heading south to the Wallowa Valley and others westward to the Snake River. Following the unmistakable trail left by thousands of Nez Perce horses, Howard drove his troops up “Dead Mule Trail,” whose steep 45-degree slopes earned their sobriquet by causing the death of many of his pack mules. Lieutenant Charles Wood described conditions on the trail as simply: “Rain. Mud. Bombarded with [falling] pack mules. Sleeping in water.” It took Howard’s column four days to reach Craig’s Ferry on the Salmon River but when they tried a crossing on July 5, raging waters swept away the few available rafts and even the cavalry could not cross. Howard spent a day impotently fumbling at the river’s edge, with the troops wondering how Nez Perce women and children could accomplish what they could not, then turned around and began a grueling and morale-crushing retreat to the crossing site at White Bird Creek. Howard marched ahead with the cavalry to reach Grangeville, but the infantry and artillery did not get across the Salmon River until July 8–9. During the retrograde march, supply arrangements fell apart and the troops were reduced to eating berries or just went hungry. Howard had not only been outmaneuvered and allowed the Nez Perce to get well ahead of him, but he had also wasted more than a week in futile marching and exhausted his troops to no end.

Angry about the delay in crossing the Salmon River and apprehensive about more Nez Perce joining Joseph and White Bird, Howard made an incredibly foolish decision to launch a pre-emptive strike on the camp of Chief Looking Glass on the Clearwater River. Despite the fact that Looking Glass had refused to join the other Non-Treaty factions and his people were on reservation land as Howard had directed, Howard became convinced owing to rumors from local settlers that they were a threat. On June 30 Howard ordered Captain Stephen G. Whipple, with 66 troops from Companies E and L, 1st Cavalry, to raid Looking Glass’s camp and arrest him. Whipple attacked a nearly defenseless village on the morning of July 1 and killed three Nez Perce, but failed to arrest Looking Glass. Instead, Looking Glass now decided to join the other Non-Treaty factions on the warpath, further widening the war. Howard’s attack on Looking Glass was utter stupidity.

Once Howard was across the Salmon River and realized that the Nez Perce had eluded him, he became very concerned about his lines of communication. He sent a courier to Capt. Whipple ordering him to take his two cavalry companies, along with two Gatling guns, to establish a defensive position at Norton’s Ranch near Cottonwood to protect the supply convoys passing by from Lewiston. He also ordered Whipple to send scouts to look for the Nez Perce in case they got across the Salmon River. While Howard’s column was stumbling along Dead Mule Trail 15 miles (24km) to the south, the Nez Perce advanced from Craig’s Ferry toward the northeast, heading to their home ground on the Clearwater. Along the way, they had to cross the Lewiston–Mount Idaho road and passed close by the Cottonwood. On the morning of July 3, Whipple’s scouts detected the approaching Nez Perce. Whipple ordered rifle pits dug around Norton’s Ranch and positioned the two Gatling guns on a prominent rise, then gathered most of his cavalry for a sortie against the Nez Perce. He sent Second Lieutenant Sevier M. Rains ahead with an advance guard of ten cavalrymen and two scouts, then followed at a distance with 70 more troopers. Around 1900hrs, Rains’s squad passed by a large group of mounted Nez Perce led by Five Wounds and Rainbow, who were concealed in some low ground. Suddenly, the Nez Perce were between Rains’s squad and Whipple’s main body and before Rains could react, a large enemy force attacked his small group from behind. One veteran Nez Perce warrior named Wat-zam-yas, apparently armed with a repeating rifle, killed four of the soldiers in the opening moments of the action. Although Rains’s men dismounted and put up a stiff fight behind some rocks, all were killed within a matter of minutes. Whipple’s main body stopped within 880 yards (800m) of Rains – whom they could not see because of intervening terrain – and listened while the advance guard was massacred. No Nez Perce casualties were suffered in the brief action. Once again, the Nez Perce took no prisoners and later some admitted that the wounded were beaten to death. Sensing a large enemy force nearby, Whipple refused to move to support Rains and then retreated to Norton’s Ranch.

On the morning of July 4, Capt. Perry led a large pack mule train from Fort Lapwai into Norton’s Ranch and took charge of the garrison, which now numbered 120 troops. At this point, the main Nez Perce body of noncombatants and horses began to move past this army post in the distance and the Nez Perce warriors decided to conduct an action to prevent the cavalry from interfering with this movement. Around 1330hrs, about 100 Nez Perce warriors appeared within sight of Norton’s Ranch and opened a steady harassing fire. The Nez Perce then did a very unusual thing in Indian warfare – they attacked a fortified position held by regular troops. Cavalrymen fired back from shallow rifle pits with their carbines and the Gatling guns fired several volleys at mounted warriors, but both weapons were too short-ranged to be effective. The Nez Perce proved adept at using dead space to get close to the post but retreated whenever they came under heavy fire. After seven hours of sustained sniping, the Nez Perce finally broke off the action around 2100hrs. Amazingly, neither side had suffered any casualties, but the Nez Perce had succeeded in neutralizing Whipple’s force while their noncombatants crossed the Lewiston–Mount Idaho Road. Small groups of Nez Perce continued to harass the cavalry at Norton’s Ranch the next morning until their people had gotten further away. By chance, a 17-man force of civilian volunteers approached from Mount Idaho and 20 mounted Nez Perce intercepted them a mile short of the ranch. One Nez Perce warrior was killed – their first combat fatality of the war – but the volunteers lost several of their horses and were pinned down in a creek. It was clear that the volunteers would be annihilated once their ammunition ran out, but Perry hesitated to act. He was probably still rattled from the defeat at White Bird Canyon and his leadership at Cottonwood was ineffectual. When some of his sergeants threatened to go help the volunteers on their own, Perry finally relented and allowed Capt. Whipple to sortie with 60 cavalrymen. Having killed or wounded five of the volunteers, the Nez Perce withdrew as Whipple approached and allowed him to bring the mauled volunteers into Norton’s Ranch.

Although Perry and Whipple had prevented Howard’s vital pack train from falling into Nez Perce hands, they had absolutely failed to stop the hostiles from moving their entire main body past them to the Camas Prairie. Two days after the fight with the volunteers, the Nez Perce reached the Clearwater River, where they linked up with Looking Glass’s group, bringing the total number of hostiles to 740, including at least 200 warriors. The various bands of the Non-Treaty Nez Perce were now united, at their strongest and on familiar terrain. Believing that Howard had given up the pursuit, the Nez Perce set up a village on the riverbank and reverted to a fairly non-warlike posture, but did build some log breastworks facing to the southwest. Having eluded Howard and Perry, they seemed to regard the war as good as over.

While Howard was fumbling about trying to get back across the Salmon River and Perry was sitting on his hands at Norton’s Ranch, it was the armed civilian volunteers under Colonel Edward McConville who took up the pursuit of the Nez Perce. The 31-year-old McConville was no amateur; he had fought as a Union cavalryman during the Civil War and then fought Apaches in Arizona before retiring to Idaho in 1873. Volunteers had been coming in from Lewiston, Mount Idaho, Grangeville and other towns since word of the initial Nez Perce raids went out and by July 8 McConville had gathered 75 men at Norton’s Ranch. On his own initiative, he sent scouts out to follow the Nez Perce trail past the post and they soon discovered the new village on the Clearwater. McConville’s volunteers occupied a hill on the west side of the Clearwater from which they could monitor the Nez Perce village and sent couriers to provide Howard with the location of the hostile camp. McConville’s volunteers then sat back and waited for the army to arrive.

Looking Glass’s campsite on the Clearwater. Captain Whipple led two companies of the 1st Cavalry in a mounted right from the woods on the right to the village, which was on the left. (Author’s collection)

Howard’s position atop the ridgeline at the Clearwater seen from the Nez Perce village. Howard relied entirely upon firepower to win the battle, which effectively ceded the initiative to the Nez Perce. (Author’s collection)

Howard was at Grangeville when McConville’s courier found him on July 9 and he ordered his tired troops to advance northward to the Clearwater. However, in the meantime, the undisciplined volunteers accidentally gave away their location and the alerted Nez Perce warriors swarmed around their position, which soon became known as “Misery Hill.” The Nez Perce succeeded in capturing about half the volunteers’ horses but were unwilling to risk casualties in a pitched battle and were content merely to keep McConville’s men pinned down with sniper fire for two days. Eventually, the volunteers ran out of food and water but the Nez Perce had grown careless. McConville led his men off the hill and withdrew when the Nez Perce were inattentive, but this meant that the volunteers were not in a position to cooperate with Howard’s approaching column.

Even though the courier from McConville provided Howard with the exact position of the Nez Perce village, his approach to the Clearwater was more of a blind probe than a direct stab at the enemy. Howard’s column reached the village of Kamiah on July 10 and crossed the south fork of the Clearwater at Jackson’s Bridge, north of the Nez Perce village and on the wrong side of the river. On the morning of July 11, Howard’s column ascended a long, wooded ridgeline on the east side of the river and began advancing in the general direction of Looking Glass’s old camp, which was actually heading away from the Nez Perce village. Captain Perry’s battalion from the 1st Cavalry was in the lead, with Captain Evan Miles’s battalion from the 21st Infantry in the center, followed by Captain Marcus P. Miller’s battalion from the 4th Artillery.

Almost by accident, one of Howard’s aides looked over his shoulder and saw the Nez Perce village in the distance, on the opposite bank of the river. Despite his muddled approach march, Howard had actually gained the advantage of surprise because the Nez Perce scouts were looking southward toward where McConville’s volunteers had been, rather than toward the northeast. However, Howard decided to order one of his 12-pdr howitzers emplaced on a ridgeline overlooking the village. By 1245hrs the howitzer was able to fire a couple of shells at the village, but the range was too great so the bombardment served only to alert the Nez Perce. A single Nez Perce warrior, Mean Man (Howwallits), was wounded by one of the howitzer shells. Frustrated, Howard ordered his entire command to shift southward to the next ridgeline so that his artillery could strike the village. However, his troops had to detour around a steep ravine, which required another hour to accomplish and which caused his formation to elongate. In doing this, Howard violated some of the most basic concepts of tactical maneuvering in the presence of the enemy. First, he committed his main body to action without adequate reconnaissance, then he squandered the advantage of surprise, finally he conducted a lateral movement across an alerted enemy’s front, which invited a devastating flank attack against his strung-out forces in rough terrain.

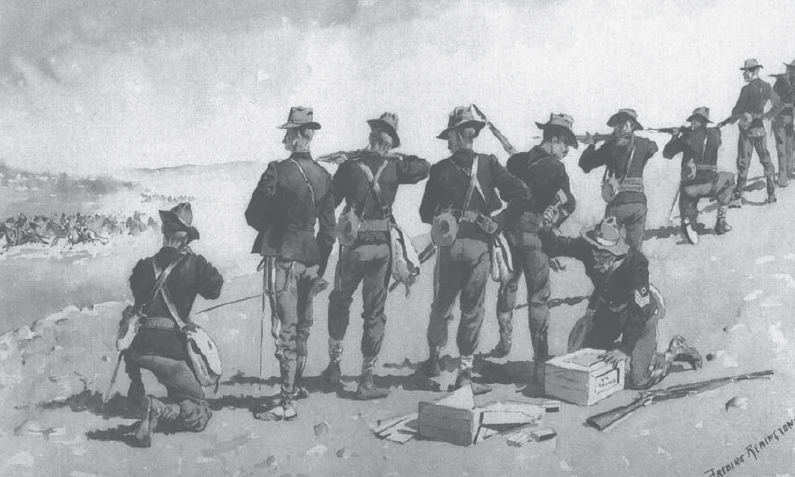

Although caught somewhat by surprise, the Nez Perce reacted to the threat with great alacrity and intrepidity. It was the aged Toohoolhoolzote who gathered up 20 warriors and led them up a deep, wooded ravine toward the ridgeline that the soldiers were approaching. It was a race for key terrain not unlike the race for Cemetery Hill in 1863, but this time Howard lost the race. Toohoolhoolzote’s warriors were able to fire upon the leading cavalry units, which disrupted the formation of a coherent line. Second Lieutenant Harry L. Bailey noted that Indian infiltrators soon surrounded his Company B, 21st Infantry, forcing the soldiers to establish an all-around defense. Bailey also noted that even though the Nez Perce managed to get within 100 yards (90m) of his position that “we could seldom see any Indians” owing to their clever use of cover and concealment. However the soldiers were almost totally exposed on top of the rocky and barren bluffs, being forced to lie down to reduce casualties from the steady sniper fire. Some warriors even managed to rush forward and capture part of the pack train, loaded with howitzer ammunition. More warriors under Ollokot and Rainbow followed up the steep ravines, sometimes engaging the soldiers at point-blank range before falling back. With his vanguard already assuming a defensive posture, Howard tried to establish a crescent-shaped formation with his howitzers on the flanks and the Gatling guns in his center. His intent was to form a powerful skirmish line, augmented by artillery, which would decimate the Nez Perce attackers. Owing to poor command and control, the 4th Artillery and 21st Infantry accidentally fired upon each other, inflicting several casualties.

Dead Mule Trail, as depicted on the cover of Harper’s Weekly on September 29, 1877. Howard’s troops spent the better part of a week crossing then recrossing this exhausting terrain, all to no end. Howard’s logistic arrangements were poor to begin with and once much of his mule train was lost on this trail, his troops were reduced to foraging. (Library of Congress)

However, the Nez Perce did not play by Howard’s rules. Instead of tackling the soldiers head-on, they infiltrated along their flanks, using the wooded ravine for cover. By 1400hrs the Nez Perce had over 100 warriors in the fight, operating in small, dispersed groups. Howard ordered his Gatling guns to fire into the ravines to clear out the infiltrators, but their barrage was ineffective. With the artillery under a continued galling sniper fire, around 1530hrs Captain Evan Miles led most of his infantrymen in a charge against the Nez Perce in the ravine, temporarily driving them back. Yet no sooner had the soldiers returned to their position than the Nez Perce infiltrators returned and mounted a bold attack against Howard’s exposed artillery. Nez Perce sharpshooters managed to kill or wound all but one gunner at one 12-pdr and nearly captured a Gatling gun. In desperation, Captain Marcus Miller launched a five-company attack with his artillerymen that drove the Nez Perce away from the threatened left flank of the perimeter. Nevertheless, the constant Nez Perce attacks on the artillery batteries forced Howard to pull them further back, which meant they could no longer shell the village. After this, the Nez Perce remained at a distance and continued intermittent sniping until about 2100hrs, when they broke off the action.

Infantry deployed in skirmish line, with the company first sergeant breaking open another box of ammunition. Unlike this idealized Frederic Remington print, troops at the Clearwater were forced to fire mostly from prone or kneeling positions in order to survive under Indian sniper fire. Furthermore, smoke from so many black powder weapons being fired in close proximity made command and control difficult, resulting in at least one incident of fratricide with one company firing upon its neighbor. (Author’s collection)

The willingness of the Nez Perce to engage in a protracted, nine-hour close-quarter battle with the US Army was highly unusual in Indian warfare, but the resolution of the Nez Perce deserted them during the night. Although Yellow Bull and a few others built stonewalled fighting positions in the ravine to block the soldiers’ access to their village, many other warriors returned to their lodges. Here, the lack of discipline weighed in against the Nez Perce, since warriors could come and go from the battlefield as they pleased. Meanwhile, the soldiers were digging shallow trenches atop the bluffs during the night, but went without food and suffered from lack of water. Howard made a serious mistake in not conducting any reconnaissance during the night or sending his cavalry to cross the river to go after the Nez Perce pony herd.

As the sun rose, sniping resumed around 0600hrs and the soldiers made a determined effort to seize a fresh water spring located in the ravine. After three hours of creeping forward, the artillerymen captured the spring and the parched soldiers could refill their canteens and brew coffee. Howard was resolved to conduct a deliberate assault on the village with his infantry and artillery, but issued no orders for the next nine hours. Instead, a minor skirmish erupted on the right flank around 1500hrs when Miller’s artillerymen moved to support a supply train approaching from Fort Lapwai and discovered that the Indian reaction was surprisingly feeble. Pushing several companies into the ravine, Miller suddenly found that he was facing only a tiny rearguard of Nez Perce warriors and he ordered a pursuit to the river’s edge. It soon became apparent that the Nez Perce had used the respite to evacuate all of the noncombatants away from Howard’s force, leaving only a small rearguard to deceive and delay. Howard pushed his infantry forward to the banks of the Clearwater but it was too deep for them to cross and by the time that Perry’s cavalrymen crossed, the Nez Perce were long gone.

THE FIGHT FOR THE HOWITZER AT THE CLEARWATER, JULY 11, 1877 (pp. 50-51)

When Howard found the Nez Perce village on the banks of the Clearwater River on July 11, he tried to use his superior firepower to overawe the enemy, rather than to close with them. In addition to two Gatling guns (1), Howard had two 12-pdr mountain howitzers (2), which he used to bombard the village from extreme range. However this bombardment failed to inflict any significant casualties upon the Nez Perce and provoked a violent counterattack by two groups of dismounted Nez Perce warriors, who rapidly moved up two ravines toward Howard’s troops atop the ridgeline.

Howard deployed his two howitzers and Gatling gun on line, supported by several companies of infantry, but they were unable to stop the Nez Perce infiltration up the wooded ravines and the crews from Battery E, 4th Artillery, soon came under accurate small-arms fire. The Nez Perce began to attack in small groups of four to five warriors each (3), which presented fleeting and poor targets for either the howitzers or Gatling guns. Finally, a determined Nez Perce got close enough to shoot five of the six crew members of one howitzer, but Private William S. LeMay (4) crouched behind the wheels and fired the piece, temporarily driving off the Nez Perce. Another group of Nez Perce nearly overran the Gatling guns. With their artillery in danger, the artillerymen of Battery E under First Lieutenant Charles F. Humphrey led a desperate charge with a dozen men and managed to drive the Nez Perce warriors back just before the guns were overrun.

Howard had not only failed to inflict any serious damage on the Nez Perce, but he had once again also allowed them to escape after a battle in which the army had clearly gotten the worst of it. In total, Howard’s force suffered 15 dead and 25 wounded – a casualty rate of nearly ten percent – but had inflicted only four killed and six wounded on the Nez Perce. The primary target, the Nez Perce pony herd, was never seriously threatened. Fearful of the political consequences of another failure, Howard sent a deliberately deceptive report of the battle, which claimed about 70 Nez Perce casualties, direct to Washington. Howard’s lies allowed him to stay in command, but it did not change the fact that he had not accomplished any part of his mission. For their part, the Nez Perce had passed up their one possible chance to end the war on their own terms. If the Nez Perce had committed all 200 warriors on the first day, Howard’s strung-out forces might have been defeated in detail and the survivors besieged atop the hill. A clear-cut Nez Perce victory would have resulted in Howard’s relief and bought time for some kind of negotiations. It was not immediately apparent, but the Nez Perce had inflicted the eventual causes of their own defeat upon themselves. In the hasty evacuation of their village, much of their food and warm clothing was left behind – which would seriously degrade their ability to fight a protracted campaign.