One

Before the Storm

The elderly Kyrgyz woman moved quickly when Chinese military trucks pulled up outside her hut on the shores of the icy Lake Karakul high in the mountains of northwestern China.

She was cooking lagman, a Central Asian dish of noodles and fried mutton, over an iron stove fuelled by sheep dung, while I sat against the wall of the hut and watched her. The woman had had a deeply lined face swathed in white cloth and wore several dresses and sweaters. She was making the noodles from scratch — leaning over a plastic tub and vigorously kneading flour and water into a dough ball, which she would then drag along the sides of the tub to pick up loose flour and bits of dough before kneeling over the tub to knead the dough again. Then she began rolling and stretching the dough, folding the lengthening and multiplying strands over and over each other each other until they were draped between her two hands like a child’s string game of cat’s cradle. The sheep dung in the stove burned hot but too quickly, and the woman would periodically pause in her food preparation to throw more dried patties into the stove. She’d open the door, toss them in, and blow on the fire. Its glow would illuminate her smudged and reddened cheeks and eyes that seemed permanently squinting, and then the door would close and her face would recede a little into the darkness.

It was difficult to see her too clearly. The air in the hut was smoky and dark, illuminated only by two candles and what little light filtered in through the greasy plastic sheeting affixed to the window. The hut’s walls were piled stones held together with rough plaster, dirt, and moss. The roof consisted of slender logs, which must have been carried in from valleys elsewhere, as there were no trees visible for miles, and woven grass mats. Patties of sheep dung were piled on top to dry out. The hut had two rooms. One, where we were sitting, was for people. Its floors and walls were covered with rough wool carpets in the simple designs and bold, primary colours typical of Kyrgyz weavers. The room next to it served as a stable. The woman and her family were nomads, and this was their summer home. Soon winter would come and they would be moving to a less punishing environment. Dusk was falling and the temperature was dropping rapidly to below zero.

An hour or so earlier, my travelling companion Adam Phillips and I had arrived at the shore of the lake and were met by the woman’s grandson, who spoke basic English and offered to let us stay in his family’s hut for a few dollars. Adam and I had known each other since we were ten years old. We had competed against each other to earn top marks in Latin during high school, and later lived together at university. We had been making our way across northern China for the previous month and hoped to cross the Karakoram Mountains into Pakistan to explore its remote northern and Tribal Areas. This was in October 2000, and what little I or most anyone in the West knew about the region was tinged with romance rather than anything sinister. The route into Pakistan from China was once a branch of the Silk Road trading route and was then the setting for covert jousting between spies of the of the British and Russian empires during the nineteenth century. Some of the mountain valleys in northern Pakistan had only been open to the outside world for a couple of decades, which is why we were there. The region seemed about as far from our homes as it was possible to get. I had been working and travelling for a couple of years since graduating university and would be starting a job in a few months. Adam had rough plans to go back to school. We were both in our mid-twenties and wanted to get off the beaten track before steady employment dragged us back on.

Lake Karakul, northwestern China.

I didn’t give the trucks much thought when I heard them rattle and rumble down the nearby road, but the old woman froze. When the trucks stopped, she dropped her noodles, blew out one of the candles, and tossed my backpack, which weighed forty pounds, into the corner of the room and threw some rugs on top of it. By now I had caught on and blew out the second candle. In the darkness I could still see her ushering me into the corner where she had thrown my bag. I curled up against the wall while she dragged several more rugs on top of me, filling my nose with dust and the pungent smell of wool. I lay there breathing heavily and trying to pull an exposed foot under the cover of the rugs when I heard the door being forced open and loud Chinese voices flooding the room. Adam was out walking near the lake. I hoped that if he saw the truck, he had the sense to stay away.

From underneath the rugs, I could glimpse the packed earth floor of the hut. I saw boots and a flashlight beam sweep the room. I heard the soldiers and the old woman arguing back and forth. The soldiers rummaged among the rugs, pots, and harnesses and came within inches of finding me but didn’t. I heard them leave the room, so I relaxed a bit, only to hear the hut’s door slam open a few minutes later. More footsteps, more lights. Then they left for good, heavy metal music bizarrely blaring from the truck’s stereo as they drove away.

I didn’t move until the old woman and other family members dug me out, all smiles and apologies.

“Army?” I asked.

“Ahh.” The old woman nodded.

“Stay in tents, okay. Stay in Kyrgyz village, not okay,” said her grandson.

China’s central government has always had an uneasy relationship with the country’s ethnic minorities — especially the mainly Muslim, Persian Tajiks, or Turkic, Uighurs, Kyrgyz, Tajiks, and Kazakhs of China’s vast, resource-rich but scarcely settled Xinjiang region, whom they suspect of wishing to separate or “split” from the rest of China. We had spent the previous week in Kashgar, a crossroads city on the old Silk Road. It still functions as a trading post. The city’s population swells by tens of thousands every Sunday as Central Asian merchants gather in a market outside the city centre to sell everything from spices, to horses, to ornate dowry chests. Strict ethnic segregation was evident in the city. The Uighurs lived in mud-brick houses with few facilities; the Han lived and worked in the concrete downtown. Uighurs staffed the shops and street-side market stalls, pushed around wooden wheelbarrows full of cement and other building materials, or hung around the mosque. Virtually every soldier, police officer, or city administrator was Han Chinese.

Muslims in Xinjiang rebelled against Chinese rule during the 1930s and declared an Independent Republic of East Turkestan a decade later. The new state didn’t last and was absorbed by the People’s Republic of China. But few Uighurs are that happy with the arrangement. Riots and uprisings in the decades since have resulted in dozens of deaths. In 2008 two Uighurs attacked Chinese border police in Kashgar, killing at least sixteen. The next year in Urumqi, the capital of Xinjiang, riots and clashes between Uighurs and Han Chinese left more than 150 dead.

The Uighur rebellions, sporadic as they are, are fuelled mostly by ethnic nationalism, resentment toward the influx of Han Chinese into Xinjiang, and anger over real and perceived ethnic discrimination. But Chinese authorities are keen to paint any Uighur opposition to Chinese rule as Islamic terrorism. They point to Chinese Uighurs who were captured in Afghanistan and later jailed at Guantanamo Bay. The Chinese case appeared strengthened in 2009, when al-Qaeda released a video in which senior member Abu Yahya al Libi urged Chinese Uighurs to “prepare for jihad in the name of God” and drive the Han Chinese from Xinjiang. There’s little evidence that this message resonates among China’s Turkic minorities, but their anger is very real. Probing where it might lead is difficult because of the restrictions China places on foreign reporters working in the area.

Even young backpackers were discouraged from interacting with the Muslims of Xinjiang when Adam and I passed through. Chinese authorities didn’t mind tourists paying to sit down and watch colourful ethnic folk dances at state-approved singing and dancing shows, but they didn’t want foreigners to talk to anyone — let alone sleep in their summer homes. Apparently there was some sort of hotel a few miles down the road where those heading for border with Pakistan were supposed to stay. Instead, Adam and I spent a long evening drinking tea in the smoky hut. Language barriers made communicating in any detail difficult. But several children in the family got a big kick out of pretending to be me, cowering under rugs in the corner while Chinese soldiers peered into the darkness.

In the morning we hiked around Karakul and into the foothills below two massive Pamir mountains that rose above the lake. Yaks and Bactrian camels grazed around us. The view was stunning, but Adam’s Chinese visa was due to expire, and we were anxious to move on. We shouldered our bags and started trudging south along the road. Karakul disappeared behind us on our left, and the teeth-like mountains that marked the border with Tajikistan rose above us on our right. At a truck stop a Chinese driver offered us a lift to the last major town before the Pakistani border for $400. “We’ll give you twenty-five,” Adam said. The driver grabbed his crotch and drove off.

Two Kyrgyz men in a jeep with no windows then pulled up. Their black hair appeared brown in places because of the dust coating it, and they wore traditional Kyrgyz felt hats. They agreed to take us for about $40. Neither Adam nor I smoked but we had brought American cigarettes as icebreakers. We passed these around along with a bag of sunflower seeds the Kyrgyz had with them. In addition to window glass, the jeep was missing most of its dashboard and part of the floor. We were already 3,700 metres above sea level when we left Karakul and now the road switched back and forth on itself as we climbed above the snow line. There were no longer any animals grazing in the mountain fields beside us, only rock and ice. The temperature plummeted further as dusk fell. We drank the tea that was left in our water bottles before it froze. We rolled past a deserted military checkpoint. A few minutes later, with daylight gone and a full moon rising above the mountains, we ran out of gas.

The driver disappeared into the night with a jerry can. He returned an hour or so later from some unseen nearby village with gasoline and a plastic tube, which he used to suck fuel out of the jerry can before spitting onto the ground and then plunging the tube into the vehicle’s gas tank so gravity could fill it up. A few cranks of the engine and we were on our way, with backslaps and Marlboros all around. The next checkpoint wasn’t abandoned. Chinese soldiers with flashlights and submachine guns waved us to a stop and berated the driver, pausing between yells to point at Adam and me in the back seat. One climbed into the car with us as we drove into Tashkurgan, the last major town before the border. Adam and I got out and slipped the Kyrgyz in the passenger seat the remaining money we owed him in the midst of a shouting match between the driver and the Chinese soldier. We checked into a rundown hotel filled with Pakistani traders and smugglers and caught a few hours of sleep.

More hitchhiking seemed like a bad idea, so in the morning we boarded a bus bound for the border. It was a rough road, but the driver was considerate enough to stop on the Chinese side so the Pakistani traders could finish the alcohol they were drinking and dispose of the bottles before crossing into officially dry Pakistan. The actual frontier was snow-swept and desolate. At almost 4,700 metres, the Khunjerab Pass is the highest paved border crossing in the world. We crossed safely and began a stomach-churning drive down the other side of the mountain into Pakistan. The air got warmer as we descended back and forth into a steep-walled mountain gorge. Marco Polo sheep bounded away from the bus, and rocks occasionally shot down the mountain over our heads. At one semi-active landslide, the bus stopped and the driver ordered all the passengers off the bus.

“What happens now?” I asked one of the Pakistani traders who stood beside me as we eyed the expanse of rubble strewn road in front of us. Small stones falling from much higher on the mountain careened off the road and went ricocheting into the valley below. The road was extremely narrow and had no barrier before a dizzying drop of several hundred feet.

“We run.”

“What? Are you serious? Why don’t we stay in the bus? At least it has a roof.”

The Pakistani was trying to roll loose tobacco into a cigarette paper. The first few passengers bolted across the landslide zone.

“If a large rock hits the bus while everybody is on it, it could be a disaster,” he said. “If the bus goes over the cliff with just the driver, it’s not such a big deal.”

Another passenger sprinted across. He was almost decapitated by a basketball-sized boulder that came rocketing down the mountain as if it had been thrown by a giant somewhere above the clouds. The trader’s fingers were shaking, spilling tobacco on the ground.

“Damn it,” he muttered, and crumpled the paper in a wad before tossing it away. The swirling wind blew it off the edge of the cliff. The Pakistani took a deep breath and took off, his woollen blanket billowing behind him like a sail. I looked up and ran after him, Adam just behind me.

When all the passengers had made it across, the bus followed. The road was full of smashed rocks that the driver had to avoid or roll over. The bus teetered, the many bells and trinkets affixed to its painted sides tinkling as it swayed. Through the bus’s dirty windshield I could see the driver’s lips moving quickly. He made it, climbed out of the bus to smoke a cigarette, and then we were on our way. Groves of poplar trees soon appeared on terraced fields below us, next to the silty headwaters of the Hunza River that gushed and roared through the bottom of the valley. Their yellowing leaves picked up the light from the setting sun and seemed to glow.

The next few weeks still appear in my mind’s eye like scenes from a pleasant dream. We watched pickup polo matches played on dusty fields surrounded by garbage and stray chickens. The players charged up and down the field with the reckless abandon of street hockey players, and spectators celebrated each goal with shouts and musical flourishes on drums and clarinets.

Our arrival in the alpine village of Karimabad coincided with a visit by the Aga Khan, Karim al-Hussayni, Imam of the Ismaili Muslims. Locals celebrated the occasion by hauling tires up mountains and, when night fell, lighting them on fire and rolling them off cliffs into the valleys below. We watched the spectacle from the roof of our guesthouse, eating skewers of yak meat that teenagers cooked and sold on the side of road, fanning the coals in their makeshift barbeques with scraps of cardboard. It looked like the mountain was spewing lava.

We hiked through and sometimes dangerously above spectacular mountain valleys. Ten-year-old boys implored us to hire them as guides. “It is very dangerous. Without my help, you will surely die,” one solemnly informed us. We slept rough but enjoyed warm hospitality almost everywhere. Strangers fed us, invited us into their homes, and pushed gifts into our hands as we left them. Outside Passu, a small village nestled between glaciers, a jeep decorated with streamers and ribbons pulled around a bend in the road with seven young men piled inside, or clinging, somehow, to its bumpers and frame. It was late in the day, and while the valley through which we walked was shadowed, above us the jagged mountain peaks shone with reflected pink sunlight.

A polo game in Gilgit, Pakistan.

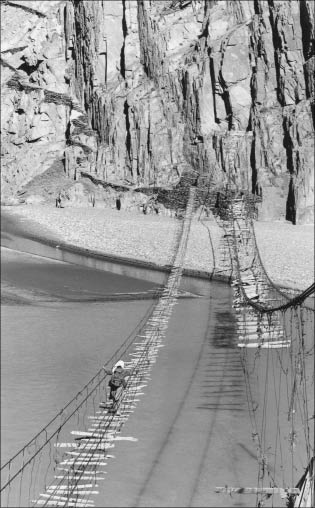

A bridge over the Hunza River in northern Pakistan.

“Where are you going?” the driver shouted.

“Passu,” I told him.

“Two hundred rupees,” he said, and everyone in and on the jeep laughed. “I’m only joking. Get in.”

There was no room to get in. Instead, we stood on the bumper, squeezed between two other young men, and hung on as the jeep careened down the mountain. I tried not to look at the drop below us every time we rounded a sharp corner. One of the men clinging to the bumper filmed everything with his one free hand. The other beside me, who had large eyes, a clean-shaven face, and curly black hair, shouted in my ear over the wind and the rumble of the engine.

“We are going to wedding,” he said.

“Who’s getting married?”

He pointed to a man in the passenger seat, not yet old enough to grow more than a wisp of a moustache, who wore white and had a large feather in his rolled woollen cap. A wide grin split his face.

“He is,” the man beside me shouted. “He is king for a day.”

It wasn’t until we left the Hunza Valley and made our way farther south, away from the company of the Ismaili and Shia Muslims who live in Pakistan’s most northern mountains and toward the more conservative, Sunni, and increasingly Pashtun areas of Pakistan’s Northwest Frontier Province, that the atmosphere around us seemed to shift — subtly at first, and then more noticeably.

The easiest means of travel around northern Pakistan, at least for those on a limited budget, is minibuses that can be flagged down and boarded pretty much anywhere. Adam and I usually rode on the roofs of these buses — the view was better, it wasn’t crowded up there, and it avoided the seat-shuffling that went on when a woman boarded the bus so that an unrelated man wouldn’t have to sit beside her. On one leg of our trip, however, we sat inside. Adam made the mistake of reaching his hand over the shoulder of a burka-clad woman to hand our fare over to the driver in front of her. Her husband exploded in anger, grabbing Adam’s forearm and hurling it away from his wife.

We left the main road south from China in Besham, a dusty, predominantly Pashtun town that serves as a gateway to the Swat Valley farther west. It was full of trucks, buses, and a sprinkling of gun shops. Many of the elderly men loitering on white plastic chairs in the dust outside the shops and teahouses sported beards dyed with henna to a garish shade of reddish orange. We climbed onto the roof of one of the many buses whose drivers were hustling for customers and settled ourselves among some loose furniture, the bags of the passengers below, and a box of explosives. When the driver had filled every available seat, the bus lurched forward and began rolling out of town, following the course of a river that gushed in torrents from the rounded mountains to our west. As we gained altitude, the temperature dropped and the air sweetened. Soon we were swaying through switchbacks that cut through pine forests. Long-haul transport trucks decorated like parade floats passed us on the narrow road with only inches to spare. But traffic was sparse, and the predominant odour in the air was not diesel fumes but moss and rotting leaves from the forests around us. At 2,100 metres, we passed through the Shangla Pass and into the Swat Valley. A sweeping expanse of green lay spread out below us.

In April 2009 a video clip emerged from the Swat Valley village of Matta. It shows two turbaned men holding a seventeen-year-old girl face down on the ground, while a third thrashes her backside with a short and stiff whip. She screams and whimpers. “Please! Enough! Enough! I am repenting, my father is repenting what I have done, my grandmother is repenting what I have done….” The girl struggles to protect herself and place a hand between her backside and the whip. The man beating her admonishes his colleague: “Hold her tightly so she doesn’t move.”

The girl was being abused according to the version of sharia, or Islamic law, that Pakistani Taliban who had taken over her village were administering. She had supposedly had an affair with a married man, though villagers reported her real crime was to have refused a marriage proposal made by a local Taliban commander, who then ordered her punishment. Such scenes were common throughout the Swat Valley since 2007, when a wing of the Pakistani Taliban, led by Maulana Fazlullah, took over much of the district, torching schools and beheading government officials.

The Pakistani state had long been willing to tolerate the presence of Taliban on its frontier. Such groups acted as proxy forces for Pakistan in Afghanistan, and the army was slow to move against them. But Taliban control spread ever closer to the Pakistani capital, Islamabad. They launched waves of suicide attacks and bombings after a bloody confrontation between the Pakistani army and Islamist students and militants at Islamabad’s Red Mosque. They are believed to have been responsible for the December 2007 murder of Benazir Bhutto, the former prime minister who had returned to Pakistan to contest the 2008 general election.

“For the first time, senior Pakistani officials told me, the army’s corps commanders accepted that the situation had radically changed and the state was under threat from Islamic extremism,” Pakistani journalist Ahmed Rashid writes in his 2008 book, Descent into Chaos. He described the situation as a civil war.

Even then the response of the Pakistani army was sluggish. The Taliban negotiated a series of peace deals or truces, which they promptly ignored and used to push deeper into Swat, clashing with the Pakistani army and driving its soldiers out of the district. The government faced a choice of finally striking back in force, or ceding growing swaths of its country to insurgents. It was clear that the Taliban were no longer content to limit their influence to the fringes of Pakistani territory. The video of the girl being viciously whipped swung public opinion behind the need for a confrontation. The month after the video aired, the army moved into Swat in large numbers. A three-month campaign followed that killed hundreds and displaced some two million people but ultimately brought the now shattered Swat district back under government control. The Taliban who had controlled it were pushed back into the Tribal Areas, where, as long as they directed their fury at NATO and Afghan forces across the border, the Pakistani military gave them free rein.

When Adam and I first saw Swat, however, this was still part of an unimaginable future. Our minibus crested a final hill and the valley opened up before us — an expanse of green framed by mountains. Adam’s body swayed from side to side as he tried to keep his balance atop the lurching and over-packed vehicle. He looked back at me and grinned. “It’s beautiful,” he shouted over the sound of the wind and the shifting gears. It was.

We began our descent toward the town of Khwazakhela, which would be the scene of heavy fighting between the Taliban and Pakistan forces in 2007. The bus stopped at a depot where a few men sold bread and patties of ground beef fried in large cylindrical cauldrons of oil. We disentangled our stiff limbs from the furniture and box of explosives on the roof of the bus, grabbed our packs, and climbed down. There were few women in the streets, and many of the men again had henna-dyed beards and wore tightly woven woollen blankets draped over their shoulders in the Afghan fashion. Some, sitting on their heels outside street-side market stalls, pulled their blankets over their heads to ward off the autumn chill and stared out at us beneath these improvised hoods. It didn’t seem like a welcoming place.

But then, minutes after we walked into a call centre in an attempt to check in with family back home, Mohammad Hayat, a middle-aged man with a shop nearby, ushered us into his shop’s backroom, served us tea, and insisted we stay for lunch. Newspapers were spread out on the floor, and on these were placed plates of rice, bowls of yoghurt and milk, chapatti, raw onions, and chicken kahari. Hayat’s friends and members of his family joined us, sitting down on mats and more newspapers spread over his shop’s dirty floor. We ate and drank everything from communal bowls, using our fingers to pick up pieces of chicken and bread or lifting bowls to our lips to drink yoghurt.

“The people we love and respect the most we feed like this,” he said. “With Muslims this is the most important thing — to be hospitable.”

Hayat had not been to Canada but mentioned a friend who had tried to visit the United States. He was denied a visa.

“They think we are all terrorists. In fact, we are not.”

When lunch was over, Ahmed, one of Hayat’s friends, led us through a labyrinth of alleys and passageways behind their shops to reach another bus stand where convoys of Suzukis were idling, their drivers waiting for passengers to take farther north into Swat. Ahmed found us a willing driver, negotiated a fare, and sent us on our way. This time we squeezed inside the bus rather than climbing on the roof. The passengers switched seats to keep a female rider from sitting next to us.

“You’ve come thirty years too late, man,” said Ali when we checked into his guesthouse in the Swat village of Madyan a few hours later. Madyan, tucked between the Swat River and a trout-filled tributary, was once a favourite stop for Western hippies trekking from Europe to India. Some were so overcome by the beauty of the place that they stayed for months, making Ali, then a young inn owner, briefly rich and very happy. Decades later, his beard flecked with white, Ali’s English vernacular was still frozen in another era.

“A lot of beautiful women were here, man,” Ali said, sitting later with us on plastic lawn chairs in front of his guesthouse. The sun was dipping toward the hills that rose above the valley and the river that ran through it. We were breaking apart and eating a kind of bright orange and impossibly sweet fruit I hadn’t seen before. Our hands were sticky. Ali was feeling nostalgic.

“They would play music. We’d smoke pot together. My favourites were the German women. They were all laid back, blonde, good-looking. Peace and love. They were the best, but all the women were nice, their boyfriends too. They loved it here. And they loved this guesthouse. They said it was like Shangri-La.” He smiled and shook his head then rolled a piece of gummy hash into a hand-rolled cigarette. The paper stuck to his juice-stained fingers. He inhaled deeply and tilted his head back, puckering his lips to blow the smoke away from his face in a tight stream.

“Do you play the guitar?” he asked.

“A little.”

“I have one inside. A Dutch man, long hair, he left it here as a present. All the strings are broken.”

“Did you learn to play?”

“Not really. The girls would try to teach me.”

Ali tried to blow hashish smoke rings and coughed loudly. “You two are the first guests I’ve had in months,” he said.

When the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan and the Islamic Revolution in Iran blocked overland routes to Pakistan from Europe, the flow of liberal-minded young tourists to Ali’s guesthouse dried up.

“I was a businessman in Europe for a while,” Ali said. “More of a salesman, really.”

“What did you sell?”

“Gems. Precious stones. Rubies, that sort of thing.”

“How did that go?”

“Not very well. I was arrested and jailed in France for two years.”

“A salesman?”

“They said I was a smuggler.”

Ali returned to Pakistan, reopened his guesthouse, and waited for the tourists to come back. They didn’t. “I’d like to immigrate to Australia,” he said.

Madyan fell to the Taliban in 2007. Scores died fighting in the area when Pakistani security forces fought to take it back two years later. I don’t know what happened to Ali, whether he ever made it to Australia or was purged by the Taliban because of his love of Western women and music. We said goodbye and caught a minibus south to Peshawar and the ungoverned Tribal Areas west of the city, where even in 2000 the Taliban’s influence was strong and growing.

Peshawar’s history has been shaped by its geography. It lies at the eastern end of the Khyber Pass, connecting Central Asia with the Indian subcontinent, and for centuries every explorer, spy, smuggler, bandit, and conquering army crossing between Europe and Asia had little choice but to pass this way. Alexander led his near-mutinous army through the pass more than two thousand years ago. The British occupied Peshawar in the 1800s and from there sent armies and secret agents into Afghanistan and beyond. During the Soviet occupation of Afghanistan in the 1980s, the city became the home base of the Afghan mujahideen resistance and their allies, who included Pakistan’s Directorate for Inter-Services Intelligence (ISI) spy agency, the CIA, and Muslim freelance volunteers from around world.

Osama bin Laden, then little more than the son of a wealthy Yemeni construction tycoon in Saudi Arabia, showed up at this time. He set up an office in the University Town neighbourhood of the city to organize the flow of Arab volunteers hoping to get a crack at the infidel Soviets or to martyr themselves in the attempt. Bin Laden gained some fame as a cash cow but wasn’t satisfied. He wanted to cross the border and fight. He established a mountain base inside Afghanistan for several dozen Arab volunteers under his command. These so-called Afghan Arabs were brave but incompetent. Afghans fighting with them recoiled from their suicidal zeal, and the military exploits of bin Laden’s foreign volunteers were of negligible impact. But when the Russians were finally driven out, they convinced themselves that they had helped defeat a superpower. Muslim piety had triumphed over the godless might of the Soviet Union. A myth was born.

It was during this period that al-Qaeda took shape. Founded by bin Laden and an Egyptian doctor, Ayman al-Zawahiri, along with a small band of Arabs who had come to Afghanistan, the group’s goal was to support jihads against insufficiently Islamic regimes around the world. The United States was not an initial target but became one when Saddam Hussein invaded Kuwait in 1990 and the Saudi royal family called on U.S. troops for protection. Bin Laden had returned to Saudi Arabia and offered to field an army of Arab veterans of Afghanistan to defend the country. The Saudi royal family turned him down. For bin Laden, the shame of an infidel army protecting the land of Mecca and Medina was too much to bear. Three years later, in 1993, al-Qaeda graduates bombed the World Trade Center in New York.

Meanwhile, the civil war that erupted in Afghanistan following the Soviet withdrawal was steadily consuming the country. Once again Peshawar cast its long shadow. In 1994, a movement of radical Islamists, calling themselves Taliban, or students, emerged in Kandahar province with the stated goal of restoring order and bringing Islamic law to Afghanistan. Many had lived in Peshawar and had studied in its madrassahs. They were led by Mullah Mohammad Omar, a one-eyed sheik from a poor family near Kandahar. Afghan refugees from the sprawling camps outside Peshawar swelled their ranks. Their base grew out of Afghanistan’s Pashtun belt and spread north. In 1996 they captured Kabul. Mullah Omar declared that Afghanistan was an Islamic emirate. He donned a cloak thought to have belonged to the prophet Mohammad and dubbed himself “Commander of the Faithful.”

Pakistan, through its ISI spy agency, had armed and funded the Taliban since its inception. It was one of only three countries in the world to recognize the Taliban as Afghanistan’s legitimate rulers. Having a friendly regime next door provided the Pakistani government with “strategic depth” as it faced off against its main rival, India, ensuring Pakistan could never be threatened from the west. And the Taliban’s training camps for jihadists provided recruits for the ISI to infiltrate into Kashmir and hit India there. The Taliban were Pakistan’s pawns and Afghanistan a client province to be exploited.

Some in Afghanistan initially welcomed the Taliban. Road travel was safer. Men who raped children were punished. But the Taliban also imposed a brutal and atavistic version of Islam. They treated women like animals, forbidding them even to leave their homes unless they were covered in a bedsheet-like burka, let alone work or go to school. It is little exaggeration to say that fun itself was forbidden. Music, dancing, flying kites, all were banned as un-Islamic. On occasion the Taliban massacred those they considered ethnically or religiously impure. In 1998 they slaughtered some 6,000 Shia Hazaras in Mazar-e-Sharif.

Their most serious opposition came in the form of the predominantly Tajik Northern Alliance, which held out in northern Afghanistan and in the Panjshir Valley north of Kabul. Here, during the 1980s, their leader, Ahmed Shah Massoud, earned his nickname “Lion of Panjshir” and the affection of millions of Afghans because of his steadfast resistance against Soviet troops, who tried innumerable times to dislodge him and could not.

Osama bin Laden watched the Taliban’s rise from Sudan, where he had moved in 1992 along with his al-Qaeda jihadist cohorts and was wearing out his welcome. The Saudi government had persuaded his family to cut off his multi-million-dollar allowance, and Egypt, the United States, and Saudi Arabia were all pressuring Sudan to kick him out. In 1996 he chartered a jet and returned to Afghanistan. Bin Laden and his fellow Arabs found accommodating hosts in Mullah Omar and the Taliban. It was in Afghanistan that bin Laden formally declared war against the United States and Israel or, as he put it, crusaders and Jews. He wasn’t bluffing. Al-Qaeda operatives bombed American embassies in Kenya and Tanzania in 1998, murdering hundreds, and two years later the group attacked the American navy destroyer USS Cole while it was harboured in the Yemeni port city of Aden.

When we arrived in November 2000, a month after al-Qaeda’s attack on the Cole, Peshawar felt like the edge of a frontier. Energy oozed from every crowded nook. Swarms of kids loudly peddled sugarcane and men on exhaust-belching motorcycles roared past pastry shops that sold rice pudding out of steel vats in their front windows. But when night fell, the streets emptied and it didn’t seem safe to linger outdoors. Just outside the city was a large smugglers’ bazaar for those who needed to stock up on supplies that weren’t readily available in regular stores. Officially, as a large sign and armed guard made clear, the bazaar was closed to foreigners. But by this time both Adam and I were wearing Pakistani-style shalwar kamiz trousers and tops, and I, being a little darker than Adam, was able to sneak past the guard to see what was for sale along the market’s main drag. Vendors on one side of the dusty street specialized in opium and hashish — huge blocks of which were displayed in storefront windows. The vendors opposite boasted equally prominent displays of automatic weapons.

We had been in Peshawar a day or two when we met Fired, an Afghan who had arrived a month before us but was well connected in the city. He had a stubbly face, a thick shock of frizzy black hair, and a gash across the bridge of his nose that was held together by a messy stitching job. He didn’t explain how he got it. Fired’s family traded and smuggled across the border, mostly carpets. He rented a shop in the city. One afternoon, as we drank tea with a few of his friends in his carpet-filled apartment, we asked Fired if he could arrange to take us to Dara Adam Khel, a town in the Tribal Areas that had been well known for more than a century — among certain kinds of people — for the crafting and selling of black market weapons.

Within seven years, Dara Adam Khel too would be swallowed by the Taliban’s insurgency. Jihadists would leave pamphlets on the town’s streets forbidding music and instructing men to grow beards and women to wear burkas. They murdered supposed spies of either the American or the Pakistani states, leaving headless bodies on the street each morning with notes pinned to the chest that outlined their alleged crimes.

But when we asked Fired about visiting the place, he wasn’t concerned. He simply sent one the kids who was hanging around his apartment into the roiling streets below us to seek out his friend, Sohail, who had family in the area.

The boy returned twenty minutes later with Sohail, a twenty-three-year-old man wearing a crisp and spotless pale blue shalwar kamiz and a warm, if slightly boyish, smile. His face was round and smooth. If he had to shave at all, it wasn’t very often. Sohail agreed to take us to Dara Adam Khel the next day, early, before any problems that might flare up in the Tribal Areas had a chance to develop.

“All these buildings, they are houses for smugglers,” Sohail said as we drove through the flat and dusty expanse west of Peshawar. He pointed out the car window at buildings enclosed by long and tall mud-brick walls that hid everything inside from the road.

“They must be rich smugglers,” I said.

“Oh, yes, they are very wealthy men. They smuggle guns, drugs, gold, diamonds, everything — to America, Canada, France, Germany, all over. My uncle, he is also a smuggler.” Sohail paused and laughed. “But my mother is finished with him now. She doesn’t want any problems for us children.”

Sohail explained that Pakistani law was non-existent where we were. Officially, it was in the hands of the tribal authorities. “But only on the roads,” he said. “If the police come into the village, the people will kill them.” Sohail said his own village was run by the patriarch of a leading family, “a very big man.” When the patriarch died, his son would take over.

Dara Adam Khel, when we finally arrived, looked like any other rural village in the area. There were a few butcher shops with goat carcasses and sides of beef hanging in the windows. Some had tables out front covered in sheep heads. Small boys stood behind them trying to wave off the flies that gathered in the rising heat. Men lounged in shadowed teahouses. But the gunfire was constant and unnerving. It began the moment we stepped out the car and continued as we followed Sohail to his friend’s house, where we reclined on rope beds for a quick meal of flatbread and sweet, milky tea. All around the village, craftsmen and prospective buyers were testing the merchandise. And every time the gunfire shattered a few fleeting minutes of quiet, I would wince and Sohail and his friend would laugh, one of them slapping me on the back.

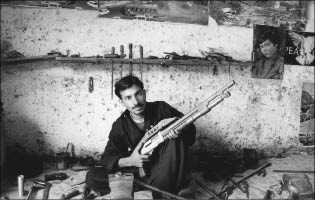

When we finished our tea, we walked into town, Sohail’s friend carrying an assault rifle slung over his shoulder. We browsed through dozens of workshops and showrooms where proud and occasionally bored craftsman showed off their handiwork. It felt like we were on a school field trip. The gunsmiths worked sitting on the floor of simple workshops and appeared to use the most basic tools. One fit a gun barrel into the wooden stock of a rifle while squatting below a large poster of a dove with the word “Peace” written on it in English. Children crouched on mats outside shops with piles of defective bullets in front of them, knocking them apart to retrieve the gunpowder inside. The most common weapon produced was the Kalashnikov, or AK-47, the assault rifle that is popular throughout the developing world and is valued for its basic design and reliability. They’re cheap and easy to repair — the preferred weapon of guerillas everywhere. Other craftsman specialized in shotguns and pistols. One designed a one-shot gun disguised as pen.

A gunsmith in Dara Adam Khel.

I asked Sohail how everyone in town learned to make weapons. “It’s a skill that’s passed from father to son. They are not doing it for three or four years. They are doing it for 150 years. My grandfather, he was making guns, too,” Sohail said, and then added: “But I’m different. I want to work as a pharmacist.”

I had grown used to the clatter of small arms fire when louder explosions erupted. Bright flashes like firecrackers appeared on a nearby cliff. Someone was hammering away at the hillside with an anti-aircraft gun.

“They’re having a marriage in the town. That’s part of the celebration,” Sohail said. “In the city, we use Kalashnikovs. Here, a bigger gun is okay.”

Before leaving we fired off a few magazines from an AK-47, bruising our shoulders and burning our hands on the hot barrel. Then we said our goodbyes to the gunsmiths. On our way out of town, Sohail’s friend, who was driving, stopped the car and a small boy, about three years, climbed into Sohail’s lap. “This is my friend’s neighbour,” he said, nodding at the driver. “He is going to be a smuggler, too.”

We stopped in the smugglers’ bazaar on our way back to Peshawar. Sohail knew one of the vendors, so it wasn’t a problem for Adam and me to be there. We drank tea in the back of the shop among enormous blocks of hash and opium. “This is the mother of cocaine,” the smuggler said, pointing to a fist-sized chunk of opium, “but you can also break off a little and put it in your tea.”

The hashish and opium seller was a young man with the thinnest wisp of a beard, maybe a teenager, cheerful and irreverent. We were soon cracking jokes and laughing until we wheezed. He must have decided he could confide in us.

“I have something truly forbidden,” he said. “Do you want to see it?”

Adam and I caught our breath. We were surrounded by automatic weapons and drugs. I had a hard time imagining what he could possibly be concealing.

“Sure,” I said.

The teenager glanced toward his shop window and then moved the prayer mat onto the floor. There was a hidden compartment underneath. He reached in and pulled out a bottle of J&B whiskey, grinning at the scandal of possessing it. In the smugglers’ bazaar, hashish and guns were readily available and dirt-cheap. A gram of hash cost about three dollars. A bottle of whiskey would set you back a hundred.

We spent another week or so in Peshawar. We wandered the streets during the day, stopping frequently for rice pudding and tea. At night, we ate with Sohail and Fired, scooping handfuls of rice mixed with raisins and carrots into our mouths from shared plates and passing around bowls of yoghurt.

One day Fired took us back to the Tribal Areas and through the Khyber Pass to the border with Afghanistan. We sat on a hill near an old machine gun nest that locals now appeared to be using as a latrine. Hills rolled below us to a village a few kilometres away, inside Afghanistan. We sat facing it, our backs to the narrow confines of the mountainous pass, and beyond that, Peshawar. Afghan boys with skinny bodies, dirty shalwar kamiz, and close-shaved heads approached and tried to sell us worthless Afghan currency. They left when we weren’t interested, circling back a short distance away and kicking the dust at their feet. Fired’s home was only a couple of hundred kilometres down the road in Kabul, but while he appreciated the relative order the Taliban had brought after years of violent conflict between opposing warlords, he was reluctant to go any farther.

“The Taliban are hard men,” he said, and he pointed at his still beardless face. “If I go back like this, six months in jail.”

Fired mixed some hashish with tobacco and rolled the concoction into a cigarette. He lit it, inhaled, and blew the smoke toward Afghanistan.

“In a few years, if there’s no fighting, come back to my shop,” he said. “No problem.”