Nine

Return to Afghanistan

Massoud Khalili stood among the fruit trees in the garden of his summer home overlooking the Shomali Plain north of Kabul and asked if I could hear birdsong. Because so many people had perished in Afghanistan’s wars, he said, he didn’t allow his gardener to shoot birds.

Khalili, son of one of Afghanistan’s greatest modern poets, Khalilullah Khalili, was a close friend of Ahmed Shah Massoud. They fought the Soviets together, and then the Taliban. He was beside Massoud in Khodja Bahuddin when al-Qaeda agents posing as journalists blew up a bomb hidden in their video camera and murdered him. Khalili, then the anti-Taliban United Front’s ambassador to India, was partially blinded and riddled with shrapnel. He still has metal shards in his lungs and eye socket. He woke a week after the bombing in a hospital bed and saw his wife of more than twenty years standing over him. She watched him open his one good eye and recited a verse from the Quran: “From God we come, and to him we will return.”

Khalili thought he might die and wanted to do so with a clean conscience. He asked his wife to forgive him if he had ever raised his voice against her in all their years of marriage. Then he asked what happened to his friends and comrades who were in the room when the bomb went off.

Some are dead, some lived, she said. Massoud is gone.

Khalili asked about the al-Qaeda agents who tried to kill him.

They’re dead, she told him.

Khalili saw his son and called him over.

“I said, ‘Listen to me. I may be dead soon. Whatever I am about to ask of you, you tell me you’ll agree.’”

His son refused, but Khalili’s wife yelled at him and he gave in.

“I said, ‘Son, I know you’re an Afghan and revenge is part of your culture. And if there is a war and you are recruited, go. Mercy to the wolf is cruelty to the lamb. But listen to me. I want to go from this life with no pain. Don’t fight on my behalf. I have already forgiven the boys who did this.’”

Khalili, when I met him in May 2011, was Afghanistan’s ambassador to Spain. When he is in Afghanistan, Khalili lives at either his summer home above the Shomali Plain, or in another house in Kabul that the late king of Afghanistan, Mohammad Zahir Shah, built for Khalili’s father. He is more of an intellectual than a politician, but he still has power and influence. He funds local schools for boys and girls and gives talks in them. He encourages moderation. “I’m a Muslim,” he said, “but not an Islamist. As I tell my Pashtun friends, ‘Be a strong Pashtun, but not a Pashtunist. Be a strong Tajik, but not a Tajikist. Be a strong Jew, but not a Zionist.’”

Pacing with gusto between the rows of trees behind his house, Khalili cradled their blossoms, described how the irrigation channels running between them worked, and talked about plans for a fountain. He pointed to a distant hilltop and said that was where Alexander the Great made his camp.

“Of all the conquerors we’ve had, we loved Alexander the most because he brought all this civilization and thinkers and philosophers with him. He conquered us with this, and we believe if he wasn’t a prophet, he was one of the saints, and God sent him to bring these things to this land.

“You know,” Khalili continued, “my father never called him Alexander. It was always Sir Alexander.”

Khalili shifted his gaze to a row of mountain peaks to the east. He traced a fingertip from one to the other. There was the route, he said, that he and Massoud would use to hike into their stronghold in the Panjshir Valley after picking up weapons and meeting with CIA spooks in Pakistan during the jihad against the Soviets.

“They couldn’t move on the ground,” he said of the Russians. “But their helicopters would just fly over our houses. Then in 1986 we got Stinger missiles. The first Stinger strike was a warning that they no longer controlled the skies.”

On another night I ate with Khalili in his Kabul house, its walls covered with his wife’s artwork. On a shelf was one of the last photographs ever taken of Ahmed Shah Massoud. Khalili snapped it when the two were sitting in an airborne helicopter. The film was in Khalili’s pocket when the assassin’s bomb exploded. It somehow survived intact, and when Khalili recovered, he developed it to see an image of his late friend calmly reading a biography of the prophets as their helicopter buzzed over northern Afghanistan. Khalili had only been back to the Panjshir Valley once since then, to see Massoud’s tomb. “It was the first time I was there alone. Before it was always with him. There was always someone there, someone tall, who I was walking with or following.”

Khalili’s mood drifted toward melancholy when he talked about Massoud and especially his death. “It matters how you die,” he said. “And he died as he promised us. He said would fight until the last drop of his blood, and he did.”

Elsewhere in the house was a photo of Khalili himself, bearded and much younger. It was taken on a mountainside in 1984, during the Afghan guerilla war against the Soviet Union. In the photo, Khalili sits on the ground, leaning back and tilting his tanned face toward the sun. There is a bandolier of bullets draped across his shoulders. His eyes are closed. He looks blissfully happy.

“The only thing we had was hope. The only weapon we had was hope,” he said when I asked him about the photo. “In the mountains, it was a dream to have a parliament and a president, and boys and girls going to school. The worst parliament in the world is still something. Because you have it.”

Afghanistan had its parliament when we met, but also the Taliban. An insurgency burned in the south of the country. Khalili feared what might be bargained away to end it. “You can’t fly with one wing broken, and that wing is women,” he said, referring to the Taliban’s views on female emancipation. “Some things are so principled that you cannot make a deal on: human rights, rights of women, education. You bring peace to Afghanistan like that, with no media, no freedom, it’s like peace in a graveyard. Stability in a graveyard is good for dead people.”

But Khalili still had hope. “I have an army now, a police, though not very strong. Despite corruption, we have money. And people have not raised their white flag to the Taliban. Some, yes. But not all.”

It occurred to me, listening to Khalili, that on the ledger balancing the costs and benefits of the war against the Taliban and the West’s intervention in this country, the fact it is a man like Khalili, rather than some backward misogynist, who now represents the government in Kabul to the outside world, must count for something.

After dinner we retired to a circular meditation room built into Khalili’s house. It had Muslim prayer rugs and also a Buddhist singing bowl given to him by the Indian government after he recovered from the 2001 bombing. Khalili sat cross-legged on the floor, eyes closed, tracing the rim of the inverted bell with a wooden mallet while a soft ringing sound rose, filled the room, and then faded into silence. Khalili or his wife had painted verses on the walls of the room. Among them were lines from Jalal ad-Din Muhammad Balkhi, the thirteenth-century Persian poet known as Rumi, who wrote about the unity of mankind. Khalili recited them in Dari and then in English:

Come, come, whoever you are.

Wanderer, fire worshipper, lover of leaving.

It doesn’t matter.

Come, even if you have broken your vow a thousand times.

Come, yet again, come, come.

My return to Afghanistan began earlier, in Kandahar. I took a military flight from Ottawa to the Kandahar Airfield, a sprawling city-like complex where NATO runs much of its military operations in the Taliban heartland of southern Afghanistan. There had been maybe a few hundred special operations soldiers and CIA paramilitaries in the country when I left in 2001. Now there were more than 100,000 foreign soldiers battling the still-resilient Taliban.

The initial campaign to overthrow them relied heavily on air strikes and special forces allied with Afghan fighters on the ground. This minimalist strategy was built on the hope that intervention would be quick and light. For a while it was. The Taliban were seemingly defeated, and a friendly government was installed in Kabul. America then moved much of its personnel and resources from Afghanistan to Iraq. The shift allowed the Taliban to rebuild. Soon a full-blown insurgency was raging.

“As they look back over this, they’ll probably figure that there were some opportunities early on that we didn’t take advantage of,” Lieutenant-General David Rodriguez, the American commander of the International Security Assistance Force Joint Command, said when we met in Kabul.

“The enemy regrouped and by 2005 was starting to come back stronger and stronger. And then we kind of were a little bit behind it each time and didn’t leap ahead to get the strength and density of forces to improve the security to enable all the other things that are important. The numbers came late. The speed and growth of the Afghan national security forces came late. And what we couldn’t do is just keep catching up to an ever-growing, strengthening insurgency, and basically shooting behind them.”

Canada’s deployment of more than 2,500 soldiers to Kandahar in 2006 coincided with the Taliban’s resurgence. The Canadian Forces suffered more than thirty fatalities that year, and again in each of the three years to come. Responsible for much of Kandahar province, the Canadians didn’t have the numbers necessary to control territory. “It has been difficult, because we weren’t a large enough force to fight an all-out counter-insurgency,” said Brigadier-General Dean Milner, the Canadian commander of Task Force Kandahar. They contained the Taliban and beat them whenever they stood to fight, but could not defeat them.

Then, in 2009, U.S. President Barack Obama announced an additional 30,000 American troops would “surge” into Afghanistan. Most of them arrived in the south. The Canadian area of responsibility shrunk. For the first time, Canadian soldiers had the troop density, as Milner put it, “to live with the people, to be everywhere we wanted to be.”

The Canadians, freed from trying to secure the entire province, deployed throughout Panjwaii district in a network of forward operating bases, patrols bases, and combat outposts. Some were large, fortified camps with rows of tanks and staffed kitchens. Others were small compounds where soldiers slept in hovels or outside and ate cold rations or whatever they prepared themselves.

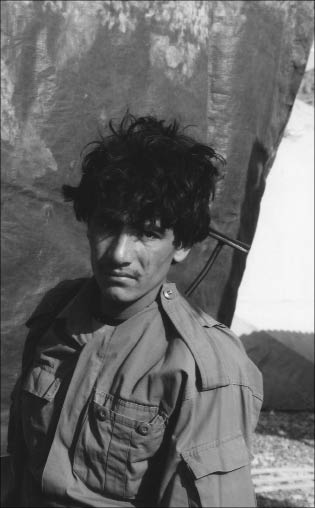

An Afghan policeman near the village of Salavat, Kandahar province.

Canadian soldiers prepare for an armoured patrol at dawn in Kandahar province.

My visit came at a time when the Canadians fighting in Panjwaii felt they had finally reversed the Taliban’s momentum. Only two members of their battle group had died due to enemy action since their deployment began the previous fall. Firefights and bombings were rare. Refugees were returning. They were opening schools. Members of the battle group, most from the Royal 22e Régiment, the Quebec unit known as the Van Doos, were proud. They had accomplished a lot. They were also on their way home. Canadian Prime Minister Stephen Harper had promised to end Canada’s combat mission by July 2011, only a couple of months away.

“As long as we’re here, our work should be to create an option,” Alexis Legros, a captain who commanded a platoon at the Folad patrol base, told me. “They chose the Taliban because they provided security. Now we’re giving them another choice. In the end it will be the population that decides. They know the Taliban closed schools and we opened one. There’s no point trying to impose anything, because it won’t work. The only thing we can do is give them time and an alternative when we leave.”

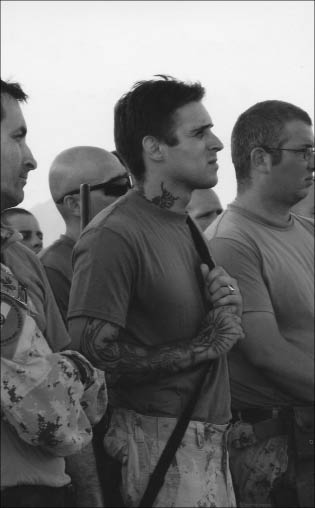

Canadian soldiers at a forward operating base in Kandahar province.

I joined a foot patrol that set out one day from a forward operating base deep in the Horn of Panjwaii to a smaller patrol base in what was once the Taliban’s backyard. As always, the soldiers carried seventy or eighty pounds of kit, including a ballistic vest, weapons, and ammunition. The sun baked. The few Afghans passing on the road were searched. One soldier told me she was no longer allowed to give pens to local children lest they end up in roadside bombs. Lieutenant-General Peter Devlin, Canada’s chief of the land staff, was accompanying the patrol and stopped to chat with two Afghan teenagers. An army photographer positioned herself to capture the moment.

“Are you going to school?” he asked.

“No,” they told him, speaking through one of the military’s translators.

“Oh. Well, do you work?”

“Yes. In the fields.”

“What do you farm?”

“Poppies and opium.”

The patrol base consisted of a tiny compound with scattered razor wire strung on some of its walls. There was a mulberry tree in the centre of the compound, a generator-run freezer, a makeshift barbecue, camouflage netting for shade, and a couple of dark mud-walled rooms where soldiers slept when they weren’t sleeping outside. On the roof were the flags of Canada and the Royal 22e Régiment and a .50 calibre machine gun. Behind the gun was an easy chair with its stuffing poking out the seams where anyone firing the weapon might sit comfortably.

Soldiers at the patrol base stayed there for two or three weeks at a time. They patrolled constantly, often with Afghan soldiers who lived in a neighbouring compound. Private Tommy Quiron said he would rather live at the outpost than on a bigger base because “we’re free to do what we want.” He had a tattoo on his shoulder: “In peace, vigilance. In war, victory. In death, sacrifice.”

Soldiers forming the patrol stepped through the dark, arched brick doorway of the compound, blinked when they re-emerged under the blazing sun inside, shook hands with those living there, and began cracking jokes in French and English. They leaned assault rifles against nearby walls. Some stripped off their body armour, revealing sweat-soaked uniforms beneath. Michel-Henri St-Louis, commander of the battle group, stood in the centre of the base, guzzling warm water from a plastic bottle. Powdery dust kicked up by marching soldiers had stuck to the sweat on his face, forming smears of white on his sunburned cheeks. They looked like sunblock or war paint. He was smiling.

“It has to be brought down to small victories,” he said when I asked him what the Canadians had accomplished that will outlast them. “It has to be brought down to a ten-year-old going to school. When he was born he couldn’t listen to music or study anything other than the Quran. Now that ten-year-old has a choice.

“So what’s our legacy? That ten-year-old was born in a very different world. It was a radical extremist government that allowed its country to be used for terrorism. That ten-year-old today has more choices. He has a school. He’s learning reading and writing — and the Quran. And he has a spark of what he can do with his life that wasn’t there ten years ago.”

From Kandahar, I booked an Afghan civilian flight north to Kabul. A young soldier from Newfoundland waited with me at the airport until the plane left. He groused, politely, about spending his tour stuck at Kandahar Airfield rather than in the field. His patriotism was unabashed. He said he wanted to fight so others wouldn’t have to. “My hometown and my province and my country are worth every drop of blood that I can give.” He wasn’t happy about Canada leaving Kandahar with the war there not won. “We’ve been in this fight so long, we’d like to see this through,” he said. “To just pack up and leave would be unforgivable. Everybody in the battle group knows somebody who has died. We’ve paid a heavy price. If we can leave an Afghanistan that’s at peace, that’s something we can put on their graves.”

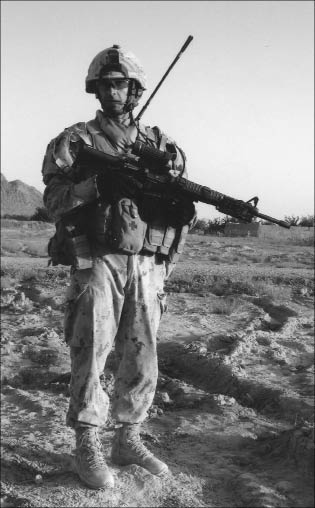

A Canadian soldier on a foot patrol in Kandahar province.

I landed in Kabul and turned on my BlackBerry. It used to take a satellite phone to reach home or anyone else in Afghanistan. Now all the emails that had been sent to me while I was flying started stacking on the phone’s display screen. One was from an acquaintance at the Canadian embassy in Kabul. I was a little surprised to see the government email address. I wasn’t planning on meeting any Canadian diplomats in Kabul, and my professional relationship with the Department of Foreign Affairs is usually strained. A request I had made weeks earlier to interview the Canadian ambassador in Kabul was ignored. I opened the email. It included a forwarded message from an allied embassy, which I later learned was the British one: “As of 11 May 2011, we have been made aware of an increased threat of kidnap to an unidentified international journalist within Kabul. Please pass this information to any journalist contacts you may have, so that their security providers can mitigate against the threat.”

I looked at my plane ticket to be sure of the date. It was May 11. As for “security providers,” I didn’t have any, banking instead on looking vaguely Afghan and keeping a low profile. It was an unnerving way to begin my visit. I shouldered my duffle bag and hiked to the parking lot, where Shuja, the Afghan friend of a friend whom I had hired to drive me around, was waiting. I threw my bag in the back seat of his beat-up sedan and shook his hand. He told me he came in third place in a Mr. Kabul bodybuilding contest. At least that was something.

We pulled out of the parking lot and immediately into a snarl of traffic. Pickup trucks in Afghanistan, the last time I was in the country, usually had a heavy machine gun mounted on the cab, or a cargo bed full of men with assault rifles, or both. It was strange, then, to see one carrying raucous teenaged members of a soccer team. They stood swaying in their uniforms, holding on to the truck with one hand and waving the other in the air. It was stranger still to see the cheering teenaged girls in the car that followed. Schoolgirls with simple blue uniforms and white headscarves picked and scampered along the broken sidewalk beside us.

Shuja wove in and out of traffic and told me his story. It wasn’t unusual. He was in school when the Taliban took Kabul in 1996. The next day several Talibs burst into his classroom and arrested thirty-five Tajik students they accused of coming from the Panjshir Valley, where Massoud and many of the anti-Taliban fighters made their home. Shuja is not Panjshiri, but they took him anyway because he looked like he might be. The Taliban held him for four days before letting him go. “I ran five hours to get to my aunt’s house,” he said. “The next day we left for Pakistan.”

He dropped me off at my guesthouse, a place with no sign out front and a bar in the basement where Afghans were forbidden from drinking. It attracted a steady stream of NGO workers, foreign businessmen, and “security contractors” still sporting the rangy, muscular frames they had acquired in previous military lives. “An airborne unit,” was all an otherwise forthcoming Brit said when asked with what regiment he had served. Elsewhere, male NGO workers drunkenly circled one of the few women there like children around a campfire. “You’re watching a pathetic display of my desperate attempt to get laid,” one confided loudly. The only Afghan in the place, the barman, looked on impassively.

My guesthouse wasn’t the only isolated bubble in the capital. NATO bases were another. They were enormous affairs, ringed with multiple layers of concrete, roadblocks, and razor wire. On occasion a contact inside could not even greet me at the farthest gate. I’d pass one checkpoint, walk several hundred metres, and meet her halfway. Some bases required fingerprints and iris scans. Staff at one wanted to know my religion.

“I’m not going to tell you that,” I said to the young American army clerk who had just taken my second round of iris scans in about ten minutes.

“You have to.”

“I’m a Jedi Knight,” I responded unfairly. She hadn’t made the rules.

“That’s not on here,” the clerk said. “You can say Jewish, atheist, Chinese …”

“Chinese is a religion?”

She shrugged.

Talk in Kabul was of President Hamid Karzai’s efforts to strike a peace deal with the Taliban. Western nations, groping for an exit, backed the process and did their best to ignore the many Afghans who did not. Some 10,000 rallied in Kabul before I arrived, to protest a deal and the prospect that Karzai might make fundamental concessions to the Taliban in an effort to reach one. “Death to the Taliban,” they shouted. “Death to suicide bombers. Death to Punjabis” — a reference to the Pakistanis many Afghans feel control the Taliban.

The rally was organized by Amrullah Saleh, Karzai’s former intelligence chief and once an aide to Massoud. Forced by Karzai to resign in 2010, he began building a political movement opposed to reconciliation with the Taliban. Beside him at the rally was Abdullah Abdullah, whom Ahmed Shah Massoud sent to Washington in August 2001 in a futile effort to warn America of the danger posed by the Taliban. I saw him once or twice that autumn in Khodja Bahuddin. He was later Afghanistan’s foreign minister under Hamid Karzai from 2001 to 2005, and then ran against him in the fraud-ridden 2009 presidential election. Saleh derided Karzai for his habit of referring to Taliban as “brothers.” “They are not my brothers. They are not your brothers. They are our enemies,” he told the crowd.

I met with Saleh soon after. There was heavy security at his office and a long wait in a small reception room where aides brought glasses of sweet juice before I was ushered into his office upstairs. Another half dozen of his aides sat on chairs against the wall there. We sat and waited some more, and then Saleh strode into the room — clean-shaven and wearing a stylish suit. He moved quickly and looked directly at the person he was speaking with. He seemed full of energy and confidence. He spoke fluent English and avoided utterly the circumlocution that afflicts many public officials. Afghan politicians often speak euphemistically about their “neighbours” or “outside countries” when criticizing Pakistan. Saleh hates the place and doesn’t bother hiding it. Islamabad, he said, wants to use the Taliban to control Afghanistan the way Iran does with Hezbollah in Lebanon. Afghans must resist this, he said, since they must fight for a pluralistic and democratic society.

“What I call the anti-Taliban constituency, it’s not ethnic, it’s not south−north. It’s a constituency that wants justice. Without implementing justice, you bow to a group that only knows beheadings, intimidation, suicide bombings, marginalization of society, crushing of civil society. That will not bring stability…. I do see the argument to have peace. I am not saying we should continue fighting. I say at what price? The current approach will not lead to peace. It will create a different crisis, far worse than what you see.”

That Afghanistan’s international allies were backing Karzai’s reconciliation efforts did not faze Saleh. He had fought the Taliban long before most people in the West had heard of them. “We were not fighting for Americans and we are not fighting for America,” he said. “Yesterday we were fighting for the protection of our dignity, and today we have raised our voices for the same purpose.”

The far worse crisis to which Saleh alluded was the prospect of renewed civil war. He suggested Afghans would fight rather than accept any reconciliation with the Taliban that compromised on the freedoms they had gained since 2001. It seemed appropriate to visit the part of Afghanistan that had most resisted the Taliban the last time the movement took control of the capital.

The road that snakes through the Panjshir Valley 100 kilometres north of Kabul is lined with the rusted hulls of Soviet tanks. Beside them, in mid-spring, are fields of new wheat dotted with bright red tulips. Cliffs rise on either side of the valley, and through its centre a silt-darkened river rushes with melt water from the higher peaks of the Hindu Kush to the north. Massoud’s tomb is here, set atop a hill overlooking the valley. A ragged man with a milky eye swept dust from the dirt path leading up to it in exchange for handouts. “Whenever I get the chance, I come to remember and give peace to my soul,” Abdul Razaq Malin, a judge who once fought with Massoud, told me when I asked why he was there.

Ruins of destroyed Soviet tanks litter the Panjshir Valley.

Most at Massoud’s tomb were skeptical about the chances of reconciliation with the Taliban. “All Afghan people want peace, but we must be clear about who is a friend and who is an enemy,” one said. “What I think is that there is only one type of Taliban. And if they come back, it will be like it used to be.”

“Wars always end with negotiations,” Malin, the judge, said. “There should be negotiations. We’re not opposed to negotiations. But the Taliban are not ready to accept the constitution. They are not willing to accept human rights and Afghanistan as a democratic country. The Afghan people will never join with a group that they fought for so long, that accepted terrorism and stomped on human rights in Afghanistan.”

Downriver from Massoud’s grave, I stopped at the home of Ahmad Zia Kechkenni, an Afghan-Canadian whose wife and kids now live in Toronto. Kechkenni is a nephew of Abdullah Abdullah. His family has deep ties to the disbanded Northern Alliance, and to Massoud’s anti-Soviet guerillas before them. We sat in his shady, flower-filled garden next to the river, drinking tea and eating almonds. Two family members lie amongst the shrubs and flowers close by. They were killed in a Soviet bombardment and buried there because it was too dangerous to take the bodies to a cemetery. A ceasefire between Massoud and the Russians was signed in the same house.

Kechkenni acknowledged the ethnic dimension of the movement opposed to peace with the Taliban. The predominantly Tajik Northern Alliance, he said, had accepted a Pashtun president in Hamid Karzai. But the Taliban “show some traditional Pashtun values. We are living in the twenty-first century. We have to come out of these tribal locks. Other ethnic groups are willing to do that.” He accused Karzai of pandering to the Taliban to gain Pashtun support. “It goes back to this tribal thing, that only one ethnicity has the right to lead Afghanistan.”

Faheem Dashty, Kechkenni’s brother, an Afghan journalist, and a former member of the Northern Alliance, had come to visit. He, like Massoud Khalili, was with Ahmed Shah Massoud at his assassination. Dashty’s hands were webbed with scar tissue, and he said his memory was affected by the blast.

“There are two extremes that come together,” he said, leaning back into a white plastic chair. “On this side we believe in human rights, women’s rights, freedom, justice, democracy. But from that side they are fundamentally against these values. They believe in a fundamentalist Islamic system, which doesn’t actually have anything to do with the teachings of Islam. If we reconcile, one side has to sacrifice its values, either this side or their side. The people of Afghanistan will not accept that. Their side will never sacrifice its values either. Our options are either to defeat them or lose the war. There is no third one.

“If we lose this war, Afghans will not lose much. What do we have to lose? A few hundred kilometres of asphalt road. A few hundred schools. Of course, we may lose our lives, as we have before. But our allies, the international community, will lose a lot. Because they have a lot to lose. The civilization that they have built up over hundreds of years, they will lose that, because this land will become a centre of terrorism. The war that we have to fight now in Kandahar and Helmand and sometimes in Kabul, then we will have to fight in Paris or Barcelona or Ottawa. It doesn’t mean that you will have active war. But they will follow you there. Before 2001 they may have had this fear that if they do something, they will be attacked. But if we lose this war, they will not have this fear. Because they will already have defeated us.”

Not all Afghans believe reconciliation with the Taliban is so fraught with risk. Shukria Barakzai is an Afghan member of parliament who helped draft the country’s current constitution. She’s Pashtun but eschews ethnic labels. “We didn’t have that disease before the civil war,” she said. “Then everyone talked about ethnicity, Shia, Sunni, whatever.” Barakzai scoffed, however, at the notion that Karzai might win over Pashtuns by pandering to the Taliban. Pashtuns, she said, are the insurgency’s greatest victims.

During the Taliban’s rule over Kabul, regime thugs beat Barakzai in the streets. But she didn’t cower, instead establishing a secret school to educate girls. Today, like all Afghan women with any sort of power, Barakzai is regularly threatened by the Taliban. Reaching her office meant passing numerous checkpoints. We met in a small ground floor room with smudged walls. Barakzai breezed in, cheerful, speaking in slightly accented English. She had wide eyes and a round, open face. It seemed she could barely be bothered to keep a thin length of cloth draped over the top of her head. It would slip back to her neck, she’d hike it up a few inches, and it would fall down again.

“Reconciliation is not an option. Reconciliation is a need,” she said.

“Let me explain what I have achieved since ten years and don’t want to lose,” she continued. “I have achieved the beautiful, wonderful constitution. And I’m proud of what I drafted for my nation. I’m really proud. That constitution says what rights the Afghan citizens get, and what jobs and duties the government has. We have to keep it. There will be no compromise on it.”

Other Afghans who also cherish the new constitution and the rights it enshrines fear those rights might be bargained away. Barakzai said this isn’t possible. “This is not something that will be in the hands of Hamid Karzai. The Afghan constitution is not a Karzai diary book that he can change, write in, or remove pages from.” And if he tries, she said, Afghans like her will not stand for it.

“I’m the one who during the Taliban years had my own girls’ school under their regime. I am the one who wore the burka for five years by their orders. I’m the one who ran a women’s organization under the Taliban regime when everything was closed and there was bad discrimination. Why? Because I’m a woman. I was the one who would not keep quiet at the time. How can you say that today I will accept whatever they want to order me? No way. Maybe in a dream.”

After ten years of Soviet occupation and a few more fighting the puppet government they left behind, in 1992 Abdul Rahim Wardak, a mujahideen commander, found himself approaching the outskirts of Kabul, with the government in the city collapsing. The trip to reach the capital from Jalalabad in the east had taken longer than he had thought, he recalled when telling me about it, because he himself had destroyed part of the road during earlier fighting. But he pushed on until the Kabul Valley opened up before him, a clear path to the capital. There, at about eight o’clock in the morning, he confronted a couple of Communist generals.

“Before that, I was always thinking if I get my hands on them I will kill them,” said Wardak, who was now Afghanistan’s defence minister. Aged seventy or so, Wardak was a large man with an expansive belly that wasn’t quite contained by the vest of his three-piece suit. He had laconic and world-weary mannerisms. A few weeks before we met, an armed attacker stormed the Defence Ministry and made it to the second floor where Wardak has an office before he was shot dead. If this rattled Wardak, he didn’t show it. He often sighed and chuckled; mostly, it seemed, to himself.

“They killed my brother and my uncle, and so many others. Two dozen cousins,” he continued, speaking of the Afghan Communists. “But then I saw them there, and they were in a weak position, and they were reconciling in peace. And I was totally different.

“You see, the source of all evil here was the Communist Party, which brought all these miseries upon us. If they didn’t do the coup, we will not be here. So they initiated everything — more than two million Afghans were killed, and there were hundreds of thousands of widows and orphans and handicaps, right now also. We were able to forgive them. So what do you think the chances are of forgiving these others?”

The Taliban, however, were not asking for forgiveness. All that spring, their bombing attacks continued, as efforts to strike some sort of peace deal persisted, stubbornly, blindly — driven by the West’s desperation to get out of Afghanistan and the inertia of ten years of unconditional support for Hamid Karzai.

“This thing has become too personalized,” said Mahmoud Saikal, a former deputy foreign minister under Karzai and a longtime diplomat, when we met in his Kabul home.

“We should have supported processes. We should have supported systems. We should have supported the democratization of the country. We should have supported strengthening the rule of law and the institutionalization of Afghanistan, as opposed to looking for a figurehead and putting whatever we have behind this person and believing everything will be fine. It’s not.

“To me, a peace deal means absolutely nothing. What is needed is to make sure this country functions. It looks like we’ve put all our eggs in one basket now, looking for peace with the Taliban. And I can tell you one thing — that after a lot of effort and many, many hundreds of millions of dollars, you may reach that peace deal. But you will have lost the Afghan people.”

I left Afghanistan just ahead of the last Canadian combat soldiers in the country. Canada agreed to keep about a thousand troops in Afghanistan until 2014 to train Afghan security forces. Other nations, including the United States, announced plans to scale back their troop commitments as well. Insurgents bombed a hospital. They strapped explosives on an eight-year-old girl and blew her up at a police checkpoint. In September 2011, two Taliban met with former Afghan president Burhanuddin Rabbani, who had been tasked by Karzai to negotiate peace. The envoys said they wanted to discuss it. At least one had explosives hidden in his turban, which he detonated, killing Rabbani.

Five years of attempted peace negotiations with the Taliban in both Afghanistan and Pakistan have failed. And it is difficult to imagine a more explicit demonstration of the Taliban’s disdain for a negotiated peace than their murder of the man trying to achieve it. The West tried not to notice. In January 2012, the Taliban said they would open an office in Qatar where negotiations could take place. Both Karzai and Washington backed the plan. Former warlords, non-Pashtuns, who helped topple the Taliban in 2001, meanwhile joined forces in a new opposition movement. They were unarmed, for the time being. But Karzai’s systematic undermining of Afghanistan’s parliament had weakened peaceful means of dissent. Old civil war divisions were re-emerging. More conflict loomed.

One might argue that it is not the job of Western soldiers to keep Afghans from each other’s throats. Our concern should be with our own safety. Osama bin Laden is dead and teenaged foot soldiers fighting to extend the Taliban’s reach in Helmand province aren’t plotting to blow up Toronto. This is true, up to a point. While international jihadists do fight with the Taliban in Afghanistan, their most significant base is next door in the Tribal Areas of Pakistan. But the border between the two countries is porous and was exploited by local insurgents and foreign radicals before and after the September 11 attacks. Surrendering Afghanistan re-opens the safe haven.

But what if large numbers of foreign soldiers are counterproductive in a fight against the likes of al-Qaeda? If the point of our presence in Afghanistan is simply to track down and kill terrorists with global reach, could this not be most effectively done through the use of spies, special forces, and air strikes? It’s a tempting proposition. A light footprint feels less like an occupation. Fewer soldiers on the ground mean fewer casualties. And air assaults cost less than lifting a country out of ruin. Such a model has also had some success in Pakistan, where missile strikes have eliminated dozens of top Taliban and al-Qaeda leaders.

It will never be enough. Terrorists are able to establish themselves in areas where they have secured support or fear from the local population. Our strategy in Afghanistan, therefore, should not be simply to kill Taliban, but to deny them the support or supplication of Afghan civilians. This cannot be accomplished with missiles from unmanned drones, which too often kill innocents as well as the intended victims, or with snatch-and-grab raids by teams of special forces. It requires resource-heavy nation building. This takes time and blood, aid workers and soldiers. Friendly villages need to be protected. Schoolteachers must feel safe. If our goal is to deny sanctuary to terrorists who wish to harm us, we can’t desert Afghanistan’s civilian population.

Even if we could pack up and leave Afghanistan to its fate without incurring increased risk to our own safety, we shouldn’t. There is an ethical case for staying. We can’t intervene everywhere. Millions die through violence or neglect all over the world, and we don’t have the will or ability to do anything about it. But we do in Afghanistan. Despite all our blunders and all the years of war, most Afghans don’t want to once again live under Taliban rule. Thousands of Afghans have died, and continue to die, fighting to prevent their return. The international mission there has local legitimacy. More importantly, it is morally right. The Taliban’s massacre of the Hazaras was genocidal, and their treatment of the female half of the population should be intolerable to civilized people.

“Afghanistan is a beautiful country,” an Afghan refugee in Dushanbe told me in October 2001, before I first crossed the border into Afghanistan. “It is worth loving.”

I didn’t understand him when he said it, and maybe I never really did. Meaning can often get lost in translation. But after being there I might have said something similar, that Afghanistan deserves all the emotions it draws from the people who live there, or even from those of us who only pass through — the longing, the hope, the frustration, the anger, the hate, and the love. It is also a heartbreaking country. It seems to chew up everything that is thrown at it. But it has been abandoned too many times already and doesn’t deserve to suffer that fate again.