There’s an American story that I like. It’s one of those stories that explode the myth that Americans don’t get irony.

After a baseball game, the coach went up to one of the players who had had a bad game. “What is it about you? You’ve got the makings of a great player. So why don’t you perform at that level? Is it ignorance or apathy?”

The player stared back at the coach and replied: “I don’t know. And I don’t care.”

Howard Schultz

Howard Schultz remembers being instantly impressed by Starbucks and its people when he met them in 1981. A few years later, he might have felt more like the baseball coach, wondering whether it was ignorance or apathy that prevented the founders from seeing the scale of the opportunity that he saw. And Jerry Baldwin might be cast as the star player, appearing to shrug his shoulders, pitching for Seattle Apathetic. But we are jumping ahead of ourselves. We need to introduce Howard Schultz properly.

Howard Schultz was born in Brooklyn, New York in 1954. He lived with his mother, father, brother and sister in the Projects: subsidized public housing. His father was a blue-collar worker, a truck driver among whatever other jobs he could find. Life was hard in the Projects, and the need to survive and cope with his environment no doubt helped shape Howard’s character.

Howard became the first college graduate in his family. To his parents’ amazement and pride, he kept rising, moving from a sales job with Xerox to the head of the US division of Perstorp, a Swedish company that was establishing a housewares subsidiary called Hammarplast. This was 1979, and Howard was 25. He was sent off to Sweden for three months’ training. When he came back, his drive and determination made him highly successful, but he was clearly never fired by a passion for the products he was selling. “Who could relate to plastic extruded parts?” he asked in the autobiographical chapter of his book Pour your heart into it: How Starbucks built a company one cup at a time.

He was very good at the job, though. Whenever he showed the slightest sign of restlessness, he got promoted. By the age of 27, he was earning a lot of money by any standards, not just by the standards of a boy from the Projects. He married Sheri, a furniture designer with a successful career of her own. To his parents, it was like a dream; he had achieved greater success than they could ever have imagined.

Yet it was not enough. He needed more, but not in material terms. He wanted to do work that would fire his imagination. As a basketball player, he had his own hoop dreams: he wanted drama, excitement and passion in his work. And he was prepared to take risks with his life to achieve it.

Because he was good at his job and noticed such things, Howard became intrigued at the relatively high level of sales that Hammarplast was making with a small retailer in Seattle. Starbucks, with only four small stores, was ordering and selling larger quantities of a drip coffeemaker than a mass retailer like Macy’s. Why was this? He decided to go and find out.

Until then Howard Schultz had never set foot in Seattle. His job took him across large parts of the country, but this north-western region was not really in the mainstream. The fact that Starbucks was Washington State’s largest coffee retailer despite operating just a few stores said a lot in itself. He could justify the visit, but at the same time knew that it was unlikely to lead to much. We can talk about luck, but the truth is that Howard Schultz analyzed sales information, investigated his marketplace in depth and, as a result, discovered something interesting to both himself and his company. On one level, it was simply good customer relations management. At the same time, none of the big coffee merchants showed anything like this initiative; none of them took the slightest interest in the fact that Starbucks was selling more and more coffee beans. They never asked the question “Why?”

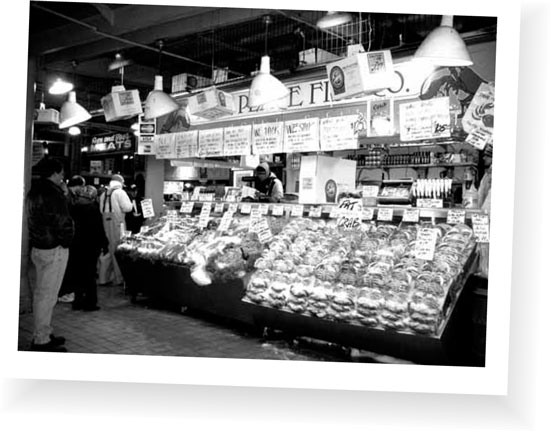

Howard Schultz arrived in Seattle in pursuit of the answer to that question. He was asking it about coffee-making equipment that Hammarplast was supplying. Asked to meet him, Starbucks’ retail merchandising manager, Linda Grossman, walked him from his hotel to the Starbucks store in Pike Place Market.

Going there for the first time in 2003, I tried to imagine the impact on Howard Schultz 24 years earlier. Pike Place retains its charm. We have all been to markets, but there is something special about Pike Place. There is still a bustle about the place that comes from the energy of finding, displaying and selling good produce rather than just putting on a show for the tourists. Tourists do flock here, of course, but they buy the marginal goods: the postcards, knickknacks, souvenir aprons. The business of the market is to sell and they do that with vigor.

Fish sellers at Pike Place Market, Seattle

Fish are sent from one end of the counter to the other, flying between the hands of fishmongers. The meatsellers have caught on and, as it is Thanksgiving week, turkeys go flying. The fruit is colorful and exotic, with pomegranates side by side with all the apple varieties of Washington State. This is a market that looks locally for fresh quality, and to all parts of the world for a taste of something different. But this is the edge of the Pacific and out there is the world’s biggest ocean, full of fish. It’s pleasant to sit at a window looking out at Puget Sound, drinking a cup of coffee, imagining the places beyond.

In American terms this is historic, the peeling paint and the chipped veneer adding to the feeling of authenticity, an age before the big chains took over. Starbucks is the only one of the current big chains allowed anywhere near Pike Place Market. That’s because it has been here since 1971, and it certainly was not a big chain then.

Pike Place Market made a big impact on Howard in 1979. He wrote later: “I loved the market at once, and still do. It’s so handcrafted, so authentic, so Old World.” Here was a man who looked back across the Atlantic for authenticity and, in a sense, approval. This feeling was reinforced by the Starbucks store. If we associate modern America with size, slickness and brashness, Starbucks seemed not particularly interested in the association. A busker outside the door played classical music, violin case open to invite small change. The shop itself was small, but inside it seemed like a temple for the worship of coffee. Like a temple it was filled with a sweet aroma – not of incense, but of coffee. There were dark wooden shelves displaying equipment, including Hammarplast coffeemakers in three different colors. And beans, beans, beans from exotic locations around the world: Sumatra, Kenya, Guatemala, Costa Rica, Ethiopia.

Howard asked the question “Why?” Why did they sell so many of those Hammarplast products? Why did they recommend them? Already he was sensing something of the answer, just by being there, absorbing the atmosphere, enjoying the aroma. “Part of the enjoyment is the ritual,” Linda Grossman explained. Howard’s understanding of a coffee ritual at this time probably centered around prising the lid off a can of coffee powder, measuring a spoonful into a cup, pouring on boiling water, and stirring in milk and sugar to taste. This was ritual of a different order. The Starbucks staff explained it in the best way they could, by making him a cup of coffee.

The counterman picked up the metal scoop, dug into the Sumatra beans, and poured them into a grinder. Then he put the grounds in a filter in the cone, and poured hot water over them. Meanwhile, Linda Grossman explained Starbucks’ belief in manual coffee brewing: the need for freshly made coffee rather than the liquid that stood around for hours in a diner’s electric coffeemaker. The sense of ritual embodied in the reverent movements of the counterman intrigued Howard. The taste of the coffee at first repelled, then converted him. It was so strong, so different. “I felt as though I had discovered a whole new continent,” he wrote afterward.

Linda Grossman then drove Howard to the roasting plant to meet Jerry and Gordon. Again, the aroma of the roasting coffee. It is true that without a sense of smell we have little sense of taste. Howard was intoxicated by the smell of the coffee, imagining he was tasting the deepest secrets of arabica. He took an instinctive liking to Jerry and Gordon, too. He liked them for their absorption in their product, for the feeling he got that they were on a mission to convert people to a love of good coffee. Yet they were very different; they had no cultish uniformity in their approach to life. Jerry was quiet and consciously the good host. Gordon was a maverick with an air of eccentricity, contributing lighter comments from the sidelines.

Whatever it was about them, they won Howard over. For him, it was a life-changing meeting. When he got back to his hotel he rang Sheri to tell her he had found God’s own country. And Starbucks was the company where he wanted to work because he wanted to learn, to explore, to discover a passion and to share it with others.

As they carried on talking later that evening over dinner, Jerry and Gordon told the story of Starbucks so far. They explained about Alfred Peet, dark roasting, arabica versus robusta beans; the way dark roasting gives fuller flavor but is shunned by the packaged food companies because longer roasting shrinks the beans, reducing the weight of the coffee. There was a clear choice between higher quality and lower cost. Believing in the intelligence of their customers, Starbucks opted for quality.

Jerry demonstrated his point by picking up a bottle of beer: a Guinness. “Comparing the Full City Roast of coffee to your standard cup of canned supermarket coffee is like comparing Guinness to Budweiser. Most Americans drink light beers like Budweiser. But once you learn to love dark, flavorful beers like Guinness, you can never go back to Bud.”

Howard Schultz’s memory of that day remains vivid. It changed his life, but it also established many of the principles of the business that he was going to grow beyond the imaginings of its founders. Becoming part of Starbucks became an obsession, and when he returned to New York he convinced himself that it was his destiny. But it was not a destiny he could rush into. He had a highly paid job for a big international company. Anyway, why would Starbucks want to take him on?

Howard’s way in was friendship with Jerry Baldwin. They met again with their wives in New York. Howard raised the subject of working for Starbucks. Jerry thought about it. He was interested and willing to put it to his partners, but also wary, perhaps because of the clash of cultures between Seattle and New York, between the laid back and the pushing forward. Would this work? There was agonizing on both sides. Howard seemed to have most to lose but was the keenest, eager to throw up a comfortable life on the east coast with a big company for the small-company benefit of a decent cup of coffee.

So it took time. A year passed. Several meetings were engineered in Seattle, and mutual trust and understanding developed. Jerry started to float the possibility of expanding beyond Seattle, perhaps to Portland, Oregon, the next state down the coast. But he was fearful of the changes that this would bring with it.

We can imagine the way the conversation was starting to go:

Baldwin: “All I wanna do is make and sell coffee in nice shops.”

Schultz: “Hire me and you can do that. Give me some room and I’ll turn this into something much bigger. It’s a jewel you’ve got here.”

Baldwin: “Not sure about that, Howard. But I guess the job’s yours anyway.”

That in essence is how it went, except for one last hitch. Invited to Seattle to confirm the deal, Howard had Sheri’s backing, his arguments rehearsed, and enthusiasm bubbling out of him. The dinner went well and they all seemed to get on. Perhaps carried away with the vision coming into focus before his eyes, Howard started talking about national and international expansion. When they shook hands at the end of the evening, he was convinced that everything had been settled.

Next day, back in New York, Howard took a call from Jerry. It was not the answer he had expected. Jerry told him that they had decided not to take the risk. He had scared them.

Howard Schultz is not a man to take no for an answer. He thought about things for 24 hours, then called Jerry again, pleading with him to reconsider.

Jerry said he needed time. He would sleep on it.

So he did. And next day he rang to offer Howard the job: head of marketing in charge of the retail stores. For a big salary cut and a small equity share – a stake in Starbucks’ future – Howard Schultz was now on board.

So Starbucks had a new marketing manager with a marketing man’s instincts. He wanted to expand the business. But Jerry hankered after authenticity, a strengthened link back to his coffee-roasting roots. He could not have been more excited when, in 1984, he got the chance to acquire Peet’s Coffee & Tea, the Californian corner shop that started it all. It was like a dream, a hippie ideal come true. But the dream kept him awake at night when it plunged Starbucks deeply into debt and landed him with the problem of commuting between San Francisco and Seattle.

Howard Schultz had other concerns, and the acquisition of Peet’s multiplied his frustrations. In 1983, he had gone to Italy to see a trade show on international housewares. The trade show made less impact on him than the visit to Italy itself. He was knocked out by Milan, a city of 1,500 espresso bars where people drank coffee outside the home at least once a day. He was entranced above all by the theatrical, perhaps operatic, nature of the barista’s movements. The barista was there behind the counter, ready to serve different kinds of coffee on request. As the barista glided from coaxing out an intense shot of espresso to whipping up a froth of milk to spoon on top, Howard was already imagining the concept transferred to Seattle and beyond. An instant insight grew into a grand vision. This would work.

The Italian coffee-house experience

“The barista moved so gracefully that it looked as though he were grinding coffee beans, pulling shots of espresso, and steaming milk at the same time, all the while conversing merrily with his customers. It was great theater. . . . It was like an epiphany. It was so immediate and physical that I was shaking.”

For Howard Schultz, as for Jerry Baldwin, the coffee was at the heart of things. But for Howard everything else mattered too: the choreography of the baristas, the relationship between the barista and the customer, the warmth, the smell, the sound, the whole experience. Above all, the sense of a community being created, a relaxed and relaxing place for people to gather.

Howard Schultz came back from Milan confessing that he had been overwhelmed by Europe, by its sense of history and its joy for life. He started thinking about how he could bring this coffee-house tradition and experience to the US, but he was keen to Europeanize the American rather than Americanize the European. It never quite works out in equal proportions, but a fusion of cultures was in his mind. This is an unusual starting point for an American-originated brand. In a sense, he acquired it from Jerry Baldwin, who was obsessed with coffee quality and learned everything from the Dutchman Alfred Peet. But Howard’s obsession was broader. It encompassed the whole idea of the coffee-shop experience, with its traditional roots back to communities and debates in the Grand Tour cities, and its umbilical cord to Italian espresso bars.

When Howard remembers the trip to Italy, something of the passion of grand opera pours out of him: “Starbucks had missed the point – completely missed it. This is so powerful! I thought. This is the link.” The opportunity he saw was to unlock the romance of coffee in American coffee bars: to liberate the idea of high-quality coffee from its location in the home, where Starbucks had always seen it. Experiencing Italian espresso bars had shown him coffee’s social power. Starbucks sold produce; it did not sell what Howard believed was the heart and soul of coffee, something that had existed for centuries in Europe. He attached words like “community” and “romance” to his vision of Starbucks’ potential as a great experience, not just a retail store.

The owners, though, were not for convincing. The Peet’s acquisition was romance enough for Jerry and Gordon. It made them feel that they had come of age as a business, like sons taking over from their father. Alfred Peet had sold his business back in 1979, so they would be buying it from people they had no ties with. They saw it almost as a duty to pay respect to the concept and to the man who had originally inspired them.

This was a crucial time for the future of Starbucks. The owners had taken on a large burden of debt to acquire Peet’s. Howard Schultz’s strategy – to experiment with the concept of an Italian coffee bar in Seattle – was cheaper. His clash with Jerry was pivotal to the future development of the brand. Perhaps for the first time, there was a feeling that Starbucks did indeed have a brand. Jerry insisted that espresso bars would take Starbucks too far from its origins: “We’re coffee roasters, we’ll lose our coffee roots.” Howard believed that, on the contrary, espresso bars would reconnect the company to its real coffee roots.

Who was right? Bizarrely, perhaps, both were right. The question takes us to the way that the Starbucks brand would position itself. A positioning like “the experience of real coffee” creates a vagueness of meaning that enables both sides to agree while making different interpretations. Brands need clarity of vision. Divergent paths were opening up. For Jerry, coffee drinking remained an experience you could savor only at home. For Howard, the experience had more resonance outside the home; he had learned from Italy that there is a home from home, a “third place” between home and work, where people can enjoy coffee and everything surrounding it: sociability, above all.

Almost as a sop to Howard, Jerry agreed to allow an experiment. When Starbucks opened its sixth store, in the period leading up to the acquisition of Peet’s, it was agreed that a small espresso bar would be included. The shop was a 1,500 square foot space on the corner of Fourth and Spring in downtown Seattle, due to open in April 1984. The space for the espresso bar was 300 square foot – half what Howard had hoped for. With no room for seating, it was little more than a counter where people could order and stand. There was a gleaming chrome espresso machine and two enthusiastic baristas who had been trained to make espresso, cappuccino and café latte. The coffee language was unfamiliar to American customers, and so were the drinks.

Howard kept reporting the results to Jerry. On its first day the shop had 400 customers, set against an average of 250 a day in the other Starbucks stores. Within weeks this grew to 800, and the growth was in the espresso bar operation. To Howard, the evidence was irrefutable. To Jerry, it was a source of further discomfort, a distraction from the core business of selling coffee beans, a wrong turning towards the restaurant business.

This might make it sound as if there were constant running arguments, but it was not really like that. Howard retained his respect and liking for Jerry, and he became Starbucks through and through in the way he committed himself to his work. Although he came from outside, he joined for a reason: he loved the passion he saw demonstrated by everyone in the business. He learned at first hand every aspect of the business. He served, he roasted, he tasted. One day he even made a citizen’s arrest of a thief, chasing him down the street to recover two stolen coffeemakers. This earned him a round of applause from the customers and did his reputation with the staff no harm.

The more he threw his personal energy into the business, the bigger the gap he saw between where Starbucks was and where it could be. Though he nagged away at Jerry, he was not winning the fundamental argument. Howard saw Starbucks’ potential as a brand that delivered an experience that could connect with people’s lives at an emotional level. Jerry took a more rational, functional approach, although he was just as emotionally committed. He saw Starbucks’ role as to educate.

Coffee can bear a great deal of educational proselytizing about its product attributes, but there are limits to the number of people who wish to be educated in this way. What interests us, what really contributes to our education, is what coffee does for us, how it makes us feel. Whether the drink in your cup tastes more or less bitter, more or less creamy, is not so important in the end. It is what the whole experience does to your spirits and your sense of self that reallycounts. If drinking a cappuccino in a coffee shop makes you feel OK with yourself and at ease with the world, then the chances are you will return to repeat the experience. So the product – the taste, color, aroma of the coffee – matters, but arguably everything else matters a bit more. This was the possibility that Howard saw, and he realized that it was apostasy in Jerry’s eyes.

Plans and visions began forming in Howard’s mind, heavily influenced by his visit to Italy. He was considering everything else as well as the coffee: the list ran from music, temperature, lighting, colors, ambience, furniture, decoration and space through to cleanliness. While writing these lines I am sitting in a Starbucks, 2003 version, in Hampstead, London. One of the baristas has just used a hand-held vacuum cleaner to suck up crumbs from the carpet nearby. “Retail is detail” is a popular saying, but it is hard for shopkeepers to live up to it every minute. Of course there will be times when the detail is not 100% right, and in a contemporary Starbucks, maintaining the brand is about maintaining lots and lots of details. Paradoxically, it would have been easier for Starbucks to get all the details right in its early days when it was focused on the product. Achieving the perfect roasted coffee bean in an obsessive way gives you license to focus less on other details generally covered by the word “service.” If Howard Schultz had a serious criticism of Starbucks in 1984, it was that its service was poor, mainly because its certainty about its own product quality led to arrogance and the unintentional belittling of customers whose appreciation of coffee fell short of the Starbucks mark.

The two men reached an impasse. Jerry Baldwin, now owner of Starbucks and Peet’s, stayed true to his coffee bean roots. Howard Schultz wanted to see where the thought planted in his mind and heart would take him. He had been backed into a corner where he could either stay, miserably confined, or leave to pursue his dream. He chose the latter, leaving Starbucks to set up his own coffee company. Strangely it was this twist in the story, Howard’s decision to leave Starbucks and establish another business, that led to the real development of the Starbucks brand.

He did it by creating a completely new brand. The name for his business was Il Giornale: “the daily” in Italian, the name of a newspaper. Howard’s ambition was to create his own version of Italian espresso bars in the US, reinventing a commodity product in the process. As when Starbucks was founded, most of the evidence argued against the new business. Analysts pointed out that coffee was the second most heavily traded commodity after oil. Moreover, it was a commodity in decline, with 20 years of falling coffee consumption in the US.

The arguments simply spurred Howard on. He believed in his concept. He wanted to take something everyday and familiar – coffee – and turn it into something desirable and sought after by building a sense of romance and community around it. His mission was to create mystique and charm, or rather to rediscover qualities that had been lost since the heyday of the European coffee house.

In the second half of 1985, Howard Schultz announced that he was leaving Starbucks to set up a new coffee-bar business. The parting of the ways seems to have been remarkably amicable. Howard carried on using an office at Starbucks while he developed his plans and drew up presentations to raise money from investors. Indeed, one day Jerry Baldwin took Howard aside and offered to invest $150,000 of Starbucks’ money in Il Giornale. Jerry saw no conflict because he genuinely believed this was a different business altogether; he still thought Howard was going into the restaurant business while he and Starbucks remained in the coffee-roasting business. Gordon Bowker was also supportive. He provided the name and many of the differentiating principles of the business: he insisted that Il Giornale had to meet people’s expectations that it would be better than any other coffee bar.

The search for investors was long and taxing, but need not concern us here. Howard made over 200 presentations, and more than 200 people said no. But enough people said yes to provide the seed money that allowed the first Il Giornale shop to open in Seattle in early 1986. Howard also had a stroke of luck as he started to recruit staff. Dave Olsen, who had run Café Allegro in the university district of Seattle and had become a minor legend in the west coast coffee world, rang Howard up and soon became an important part of his plans. Howard describes him as his coffee conscience. While Howard trudged from meeting to meeting trying to raise money, Dave concentrated on getting all the details of coffee and shop right.

Though Il Giornale started as a single store, it was always intended as a chain. The first outlet became Howard Schultz’s testing ground. There he learned how to raise money and to nurture people; to lay the foundations of a brand by establishing a culture and values; to take care of all the retail details; and to see that the fundamental beliefs he formulated drove every decision and set every objective for the business. Everything matters. That phrase later became part of Starbucks’ philosophy, but it was forged in the gleaming metal and hissing steam of Il Giornale.

Not that Howard sat down and drafted out his values. He simply allowed them to emerge from what was now a powerful combination of himself and Dave Olsen. He later expressed it like this: “If every business has a memory, then Dave Olsen is right at the heart of the memory of Starbucks, where the core purpose and values come together. Just seeing him in the office centers me.”

Il Giornale was a brand in the making. It had the obvious outward trappings of a brand, a visual style of its own. Its logo embodied its emphasis on speed: the head of Mercury, the swift-footed messenger of the gods, was surrounded by a green circle bearing the company name. Staff dressed in white shirts and bow ties, and recordings of Italian opera were played throughout the day. On the Italian coffee bar model, there were no seats, just a counter to stand at. Customers could take down a newspaper to read from one of the rods on the wall. The menu was, at least to the eyes of Seattle customers, incredibly foreign, filled with Italian words.

The shop did well, but things had to change. Though the numbers were good, it became clear that they would be better if the bow ties went, the opera was replaced by something lighter, and a few chairs were added. After six months, the store was serving 1,000 customers a day, and a second store opened in Seattle. A third store followed soon after in Vancouver, Canada. Already Il Giornale was an international business, the signal that Howard wanted to send his investors early.

Then in March 1987, something extraordinary happened. Jerry and Gordon put Starbucks up for sale. And Howard bought it.