You know when a brand has become an everyday part of our lives. It enters popular consciousness and becomes a reference point that everyone understands and laughs at. In the 1990s, the comedian Janeane Garofalo appeared on a TV comedy show and joked, “They just opened a Starbucks – in my living room.”

Equally you know that a brand has reached a position of confidence about itself when it uses such jokes in its annual general meeting. Investors at the introduction of the 2003 annual report were shown a video with a whole succession of clips about Starbucks, including the following from a spoof news report: “The iceberg is easy to spot because it’s 50 miles long and has three Starbucks.”

From this it seems that Starbucks has come to terms with its own ubiquity. Perhaps it senses that the world has, too. Over the last ten years, life for Starbucks has been a roller-coaster ride, but two particular streams have consistently run through everything. The first is increasing internationalization, which will be dealt with in this chapter. The second, against the background of debates about globalization and a growing distrust of corporate America, is Starbucks’ commitment to communities, which I will cover in the next chapter.

By 1995, Starbucks had emerged as the US speciality roaster that could bring you real coffee in the form of beans to your home or an espresso to your high street. The big coffee merchants had overslept; they simply had not noticed the significance of what was happening. Yet Starbucks was still a North American phenomenon. The company had expanded out of its north-western corner of the US into the major cities and into parts of Canada. It had even opened in New York, despite misgivings and analysts’ doubts about whether the concept was truly portable. Queues outside the shop seemed to indicate that it was. In many ways New York strikes me as a separate country within America. Perhaps “conquering” it gave Starbucks the final proof it needed that it could and should export its concept to other countries. To do so, it put Howard Behar in charge of international development.

It was a sign of growing confidence in the brand. Starbucks had always insisted on the need to build the brand one cup at a time, one person at a time, and this focus on the individual customer became one of the building blocks of the brand. Indeed, “one brick at a time” seemed to be the way the brand was built strong. The third place. The mission statement. The principles and values. The brand mantra. There were now many building blocks that reinforced each other, whereas with other brands such a plethora of statements would imply internal contradictions and confusion.

One other statement of positioning, associated with the concept of the third place, became another of these building blocks. The statement went along these lines: Starbucks offers a taste of romance because it provides a touch of the exotic in everyday life, with coffees from around the world. It is an affordable luxury that brings a certain democracy because its products, although often premium priced, are still reasonable as a treat to most people. Starbucks provides an oasis where people can take quiet moments to gather themselves and their thoughts. And it offers a place for casual social interaction that works even though the result is often the sociability of being out in the world while remaining private with your own thoughts.

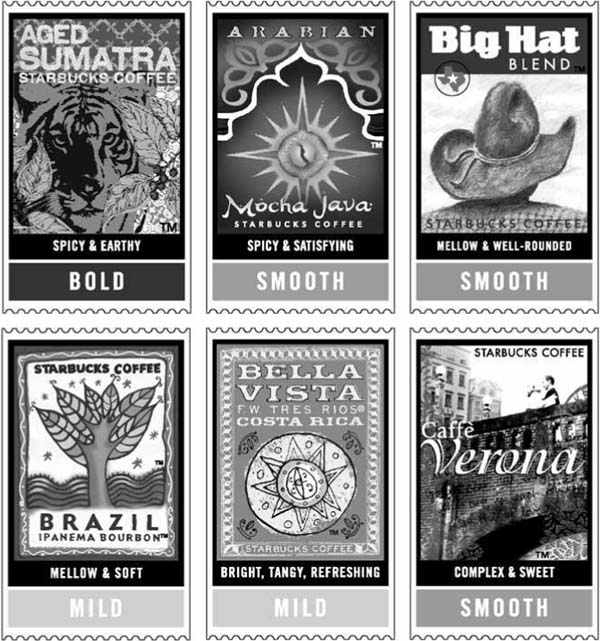

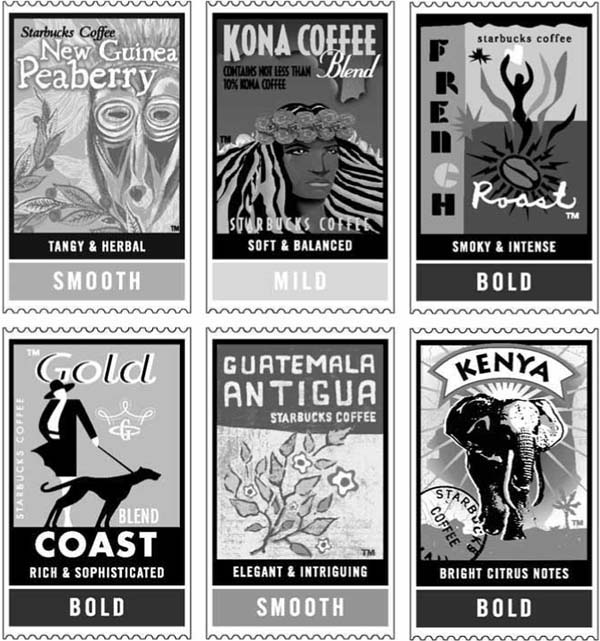

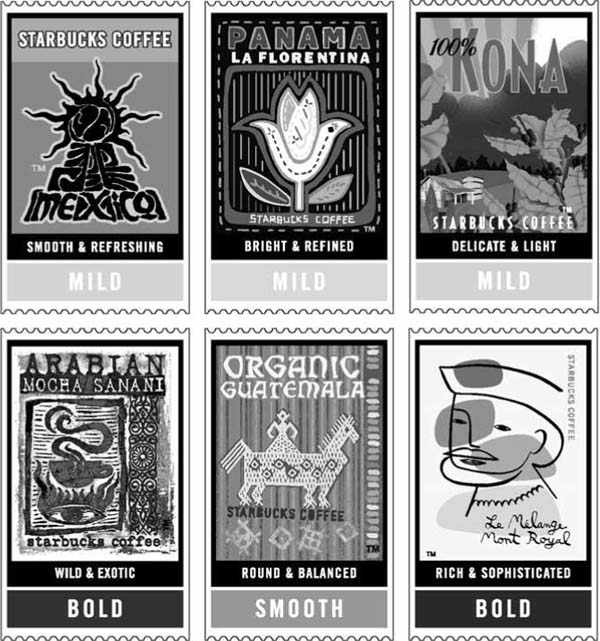

In even simpler terms, it became clear that for customers, the Starbucks brand was in almost equal parts about the coffee, the people and the experience. The way this was achieved was through a word that is one of Howard Schultz’s favorites: romance. So Starbucks needs to romance the bean, which means being fanatical about the quality of the coffee bean itself and about every step that is taken to place a cup of coffee before the customer. It means sourcing the best arabica beans, shipping and storing well, roasting the beans to an exact specification, and grinding, brewing and serving them to high standards. Every detail matters, including the quality of the water and the time it takes (between 18 and 23 seconds) to make the perfect espresso. This all makes a narrative in itself that provides an element of romance because it goes way beyond measuring a spoonful into a cup and pouring on boiling water. In other words, it’s easy to make a bad cup of coffee, but there’s something of an art in making a good one.

The range of Starbucks’ coffee is part of the romance of the bean

But the concept of romance then goes beyond this to romancing the customer, because Starbucks’ people are essential to projecting the brand. The interaction between partner and customer is fundamental. As Howard Behar put it: “We’re in the people business serving coffee.” So Starbucks needs to hire people who can interact comfortably, be easy, friendly and welcoming, maintain good eye contact, and listen to customers’ needs. Natural instinct can be reinforced through training, not only in the ways of coffee but in the values of the brand, starting with respect and dignity. All this helps to retain baristas, who stay longer and get better at their jobs, establishing relationships with regular customers.

Finally, it’s about romancing the senses, creating the complete experience in store by using all the senses. “The stores are our billboards,” therefore they have to express what the brand is all about: the smell of the coffee, the taste, the feel of the furniture, the look of the murals, the sound of the music. If you are to create the right experience, everything matters. Behind every decision is a judgment about truth to the brand: will this support or undermine it?

If these were building blocks added to those already in place, the structure was now becoming stronger. They represented layer upon layer of extra meaning rather than, as is the case with many big brands, a synthesis of meaning on one sheet of paper or in a single diagram. Unilever, for example, uses a “brand key” for all its brands, and this imposes a discipline of concise expression on all its brand managers. Starbucks goes a different route: because it insists on the continuing importance of intuition, it doesn’t want to distill its brand into a one-page statement. With Starbucks there is always more, a deeper level of understanding below the one you have achieved, and this makes for a deep and continually evolving brand that still manages to achieve a remarkable degree of consistency.

These were live issues when plans were being made for international development. What is the essence of the Starbucks brand? Can we bottle it and send it over to Japan, and throughout Asia? It turned out that Japan was the first and biggest test for the portability of the brand. It was clear when I talked to Howard Schultz eight years later that the entry to the Japanese market remained vivid. The company took it very seriously, even commissioning a blue-chip consultancy to advise on Japan. For Starbucks, with its leaning towards do-it-yourself, this was almost a revolutionary act. Yet its reaction to the consultancy’s recommendations showed Starbucks remaining true to its habitual trust in instinct.

When the study landed, heavily, on the boardroom table, it came out with a clear recommendation not to enter Japan.

There were three main objections:

1 Up to 90 percent of the business is take-away, and Japanese consumers would never be comfortable drinking coffee in the street.

2 The no-smoking policy would disenfranchise young Japanese, who would avoid stores that banned smoking.

3 The high cost of real estate in Japan would necessitate only small stores.

Starbucks listened and discussed the findings. Apart from Canada, it had no experience of overseas operations. Here, at the first time of exploration, they were being heavily warned off by a large, experienced and expensive management consultancy.

Starbucks had been doing its own homework. It had decided that it was interested in the Pacific Rim initially because Europe was already a mature coffee-drinking region. Japan, on the other hand, was a potentially large and developing coffee market. Other companies were starting to develop the market; if Starbucks hesitated, it might find it impossible to enter Japan later. Starbucks’ management resources were stretched thin, so it could not afford to hedge its bets by, say, testing Japan at the same time as a “friendly” market such as the UK. It was Japan now or never. So a joint venture was set up with the Sazaby company, whose brand and cultural values were felt to be similar. Yuji Tsunoda, a man who had lived in Los Angeles and believed that Starbucks would appeal to the Japanese, became head of Starbucks in Japan.

For Westerners, perhaps particularly for Americans, there is a wariness about the cultural gulf with Japan. Perhaps this is all the greater as it has reached a level of mythologizing through opera. Puccini’s Madame Butterfly and Sondheim’s Pacific Overtures, at different poles of a century, have placed the cultural divide at the center of an artistic exploration. But Japan has generally remained as inscrutable to Western eyes as Noh theater.

The anecdotal and statistical evidence presented to Starbucks showed that the Japanese liked coffee. Indeed, there was a growing local chain called Doutur, with 500 coffee shops. Starbucks believed it could offer higher quality and greater range, while appealing beyond the market of the salaryman to younger people and to women. But there were those three big objections, standing like guards at the gates of Japan. How should Starbucks react? The answer, inevitably, was to stick to the principles of the brand. Starbucks decided to press ahead with its decision to open stores in Japan, and it set the pattern for most of its international developments by entering into a joint venture with a locally focused company. Starbucks addressed the objections that the management consultancy had raised, and answered them in its own way. Howard Schultz still declares that he is not a big believer in consumer research; the Japanese experience will have reinforced his belief that it is real customers buying in your stores who provide the only true picture.

Starbucks’ reaction to the consultants’ third objection – high rents will mean small stores – was to remain true to the idea of the third place. Because customers who live and work in cities like Tokyo have relatively small homes and long commutes, there was an opportunity for larger stores that would be like extensions of the home. The rents would inevitably be high, but there was a belief that the greater density of population would make it pay to have more spacious stores rather than tiny kiosks.

The second objection – no-smoking stores would deter young Japanese – went to a fundamental principle about the relationship between the product and the brand. Starbucks had a no-smoking policy for a particular reason. It was not to make a health statement or take a moral stance. Because Starbucks placed such a high value on the quality of its coffee, it wanted to protect that quality. Coffee beans are highly absorbent: they take in smells from the environment around them. The simple fact is that smoke harms the coffee bean’s flavor and aroma. Starbucks’ first two stores in Japan had designated smoking and no-smoking areas, but by the opening of the third store the policy had reverted to no smoking in any Starbucks store. (This policy has remained, even in a country like Spain where there is a tradition of heavy smoking. It has become a differentiating factor that sets Starbucks apart from other coffee houses.)

The first of the consultants’ objections – the Japanese would not take to drinking take-away coffee – was harder to counter. It had to be a case of “try it and see.” In the event, if there was a cultural taboo about drinking coffee on the street, it was shattered in minutes. The Starbucks team were thrilled to see Japanese businessmen, students, mothers with children, women out shopping, all clutching their paper cups of coffee. And were they actually showing off the Starbucks logo for others on the street to see? It looked like it.

Hong Kong

Athens

Shanghai

Perhaps what Starbucks had not quite anticipated was the Japanese attraction towards brands they see as cool. Sometimes, as with Hello Kitty, this can be puzzling for people from outside Japan. But if you market your brand with the right degree of cool, the Japanese will spread their love for it by word of mouth. And they want to be seen to be associated with it, whether it’s wearing the T-shirt, carrying the shopping bag or drinking from the coffee cup. They express their individual likings as groups, too, so Starbucks became adopted in batches rather than simply one by one.

Things have settled in Japan since that first caffeine rush, but it remains one of Starbucks’ most successful markets. The Japanese service culture and commitment to teamwork played well to Starbucks’ own beliefs, so despite fears about a cultural clash between nations there was no cultural clash at a working level. Within five years, there were 300 Starbucks stores in Japan, the Japanese partners had their own stock option program, and the company was listed on the Japanese stock exchange. Whereas Starbucks initially and cautiously saw the target audience as young women, experience showed that the appeal was much broader. Japanese fan sites pop up on the internet. In Tokyo, a Starbucks in an upmarket department store is frequented by wealthy women who bring their children with them, although that had always been considered another cultural taboo.

Yet in other ways Starbucks has adapted to fit into the cultural background, with green-tea Frappuccinos and smaller cups to suit local preferences. Size does not matter – perhaps the hardest message for an American company to accept. The message that was easy to understand was that the traffic count (number of people passing through stores) is 33 percent higher in Japan than in the US. It is interesting, too, that whereas the take-out business represents 75 percent of sales in the US, it is just 25 percent in Japan.

Starbucks knew from a very early stage that Japan was going to succeed. People understood and liked the brand; there was no cultural disconnection. So it pressed ahead internationally while also moving forward on many other fronts. Stores opened in Singapore and Hawaii. Some of the remoter areas of the US – Arizona, Utah, Idaho – became part of the Starbucks map. A deal was struck with the Westin Hotels group. Continuing product development led to the introduction of Starbucks ice cream, which quickly become the number one brand of coffee ice cream in the US. Starbucks was on a roll and seemed unstoppable. That in turn led to a certain amount of resistance, because people always like to feel they have a choice. Scott Bedbury tells a story about meeting local objectors to Starbucks in San Francisco; their criticisms were that Starbucks would lead to the demise of local shops and reduce choice. The criticisms were largely defused by journalists asking how the employment policies of the local shops compared to Starbucks’. Time has shown that, in fact, greater choice has been created because the competition has to improve. If the local shops are good, they survive and thrive.

Starbucks has thrived in almost every market it has entered because it has looked after its relationship with its own people. It knows that brands are ways of making easier connections between people. Everything starts with the attachment between the company and its partners. This results in lower levels of staff turnover; indeed, high levels of retention in a notoriously volatile industry. The relationship with local business partners is important too, because in most international situations Starbucks teams up with a local partner. The only market entry that seems not to have worked – Israel – failed because there was a conflict between the standards Starbucks wished to see (the same as everywhere else) and the standards the partner could deliver. Starbucks withdrew because it felt its brand was being compromised.

That was a blip in a relentless and generally smooth stream of openings in different countries. The Philippines were followed by Taiwan, Thailand, New Zealand and Malaysia, populating the Pacific Rim. The same pattern was followed: hire a local public relations company, eschew advertising, select a flagship location, produce local artwork, retain the core products, adapt fringe products to local tastes, and produce everything to high quality with friendly, trained baristas. These have become entrenched principles.

There is a deeply held belief that word of mouth is more authentic, honest and effective than advertising for Starbucks. That puts more responsibility on the brand, and particularly its people, to deliver. So Starbucks takes great care when selecting the right business partners for different markets around the world who will understand its standards and take them to heart. When recruiting starts, new partners (managers and also, at least for first stores, baristas) will be brought to Seattle for training and immersion in the practicalities and the principles. Training lasts between 12 and 16 weeks. Standards for quality, cleanliness, service and speed apply internationally, but the personality of the barista is seen everywhere as the essential expression of the Starbucks brand. The aim is to connect with customers, not just hurry them through. But in the US speed is all-important, whereas in Japan meticulousness is what matters, and people are more prepared to wait in line.

Starbucks started to learn these nuances and find ways to introduce flexibility to local markets. Much of this comes down to trust: everyone trusting the brand, and Starbucks trusting its partners. Local autonomy and personal responsibility are vital to the way Starbucks operates. Two-thirds of employees are part-timers, but Starbucks has always made a point of treating its part-time staff with equity (literally in the sense that stock options are offered to part-timers, too). Clearly it is likely to be more difficult to establish trust with employees who have a lesser commitment in terms of hours worked. But if they were to show less commitment in their work, it would undermine the brand, so efforts are taken to look after people well whether they are full-time or part-time. At the same time, there is a realization and a deep belief that adherence to its principles is an important element of the contract with employees: “If we compromised on quality or on our values, we would have a revolt,” said Orin Smith.

This starts to sound almost military in its planning and precision, but the reality is inevitably different. Starbucks remains an entrepreneurial company, perhaps especially in international markets. It has learned to go with its intuition, and this has led to some developments that admittedly are opportunistic. Soon after the opening in Japan, Starbucks was approached by “some great people” (Orin Smith’s words). The opportunity was to work in partnership with a local company to open Starbucks stores in the Philippines. The market research suggested that the Philippines was a relatively poor country, and the national income levels might not support much of a Starbucks presence. However, there was a good rapport with the potential partners, so a deal was struck and Starbucks opened in the Philippines in 1997. Beyond all expectations, its presence has grown to more than 50 stores in six years.

I interviewed Orin Smith with two French journalists from Figaro and Le Monde. The journalists kept returning to the question of prices. “What is the price of a Starbucks coffee in Indonesia? What is the average weekly wage?” Knowing that the two answers are far closer than in the US, they kept professing surprise. If Starbucks were simply a product, their surprise would be understandable, but its success in the Philippines represents clear proof that it is in fact a true brand. People are willing to pay a relatively high price for what they perceive as a treat, a just-affordable luxury, because they are buying much more than simply a cup of coffee.

Asia was well on the way to being Starbucks adopters. Europe beckoned. You sense that there was a slight holding of breath at the prospect. Howard Schultz, in particular, had always regarded Europe and its coffee house tradition in some awe. It seemed that little education would be needed: Europeans understood coffee more deeply than people in other parts of the world. But that made the whole thing all the more challenging. The UK, however, seemed the natural place to start. There were no language difficulties if we discount George Bernard Shaw’s dictum about two countries divided by a common language. And there was a chain called the Seattle Coffee Company, with 65 retail locations, that Starbucks could acquire.

The Seattle Coffee Company, as you might imagine from its name, had been built on the Starbucks model by people who had Starbucks connections. It was a benign acquisition: the two companies had a lot in common, including a shared interest in books and literacy. The Seattle Coffee Company was one of the coffee companies that had opened outlets within Waterstone’s, the UK’s leading bookseller. In the US, Starbucks had had stores within Barnes & Noble bookshops since 1993. The association seemed right to enter into the traditional spirit of European coffee houses as places for ideas and intellectual stimulation. The acquisition went ahead in 1998 and the Seattle Coffee Company stores were quickly rebranded as Starbucks. Overnight, as it appeared to British observers, Starbucks had established itself in the UK.

It took time for this to work financially. Orin Smith smiles ruefully at the cost of British high street rents. Some mistakes were made with locations; some of these mistakes were inherited. Although business was good in terms of people in the coffee houses, it took some time to work towards profitability. Since 2002 this has started to happen, as Starbucks has settled into the market and begun to feel the strength of its brand principles. In particular, the community aspect of the brand (about which I will say more in the next chapter) speaks well to British people, who have a strong identification with the places where they live and work – and a natural tendency to be suspicious of outsiders. With the passing of time Starbucks is seen as less of an outsider as word gently spreads of its involvement in local and national good causes. The UK has grown to be Starbucks’ third biggest market in the world, behind the US and Japan.

Cathy Heseltine, the marketing director for Starbucks in the UK, is conscious of simultaneously modeling the UK Starbucks on its antecedents and finding a unique voice and style for the local market. The brand is multilayered, and little is written down by way of rules or definitions. This gives Starbucks in the UK the flexibility to play slightly different tunes around the pillars of the product itself, commitment to social responsibility and the in-store experience. At the same, time there is a determination not to mess with things. Respect and dignity are the starting points for the Starbucks working experience in the UK just as in the US. The emphasis lies on recruiting the right people, training them well (in the London equivalent of the Seattle support center) and building retention by encouraging adult relationships with the company and communities. In the spirit of “It’s coffee, stupid,” there is a constant reminder of the business’s starting point – meetings begin with a coffee tasting.

While the coffee is the immutable core of the experience, other products reflect local tastes. Granola bars sell well in the UK but have yet to make the flight across the Atlantic or the Channel. A new variety of Frappuccino – strawberries and cream – was developed initially for Wimbledon tennis fortnight, but has now been extended to a year-round product. Innocent Drinks, one of the youngest and trendiest brands around, was brought in to develop a new range of fruit drinks for UK stores. “Juicy waters” are selling well, and the Innocent brand provides a complementary, but not threatening, association for Starbucks.

If Starbucks in the UK has been a patient process, putting down ever deeper roots in communities, success came more quickly in other overseas markets. Hong Kong and Korea were immediately profitable, and the Middle East has grown quietly as Starbucks adapted its style to local sensitivities. “Who will be attracted to Starbucks stores?” is always a key question in the developed markets. The demographic profile has been steadily broadening, but the brand appeals to a wide range of people worldwide. In Arabic countries there are special issues, including the separation of the sexes in Saudi Arabia. The way to handle this is partly shown by the discovery that in the Middle East, the “average customer” is a family, so Starbucks stores are divided into men-only and family areas. Each market has a slightly different take on Starbucks; each market adds a local layer to the mix. In South Korea, this extends to trading in the biggest and tallest Starbucks in the world, a building of five storeys.

Perhaps the most surprising place to find a Starbucks was in Beijing. I had gone there as a tourist over the Millennium New Year and was making my way to the Forbidden City when I came across a Starbucks. Stepping inside, smelling the coffee, hearing the music, I encountered the authentic Starbucks experience. It was not a Chinese experience, though. Starbucks has grown especially fast in Shanghai, opening 15 stores within a year, and South China has become a thriving region. The appeal for the local audience is largely to do with its foreignness and association with comfort, luxury and freedom, qualities that the nation was denied for many years. Starbucks stores are now seen as beacons of China’s changing social and commercial environment.

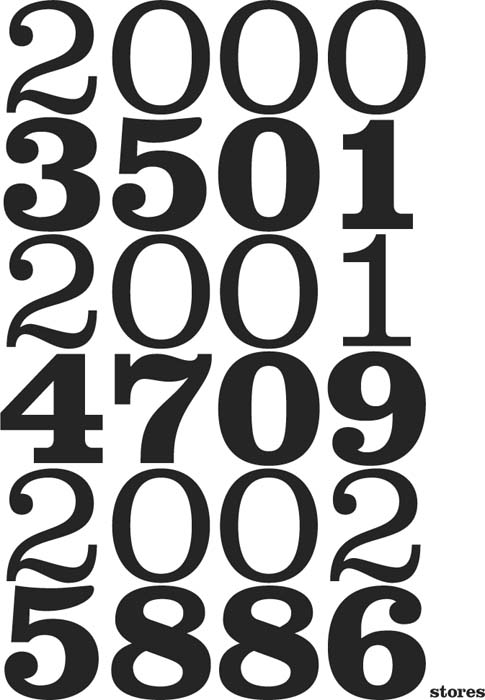

By the end of 2000, there were 3,501 Starbucks stores worldwide; by the end of 2001, 4,709; a year later, 5,886. The latest total, at the beginning of 2004, is 7,500. New shops are opening at the rate of three a day. Like an empire, the sun never sets on Starbucks. Size always carries dangers, particularly if growth is seen as greedy, but Starbucks has gained a momentum that is hard to stop. There are now Starbucks stores in every US state, yet the market is still relatively untouched (Starbucks has only a 7 percent share of “coffee opportunities” in North America as a whole). Starbucks is located in 34 different countries around the world, yet its purchases represent only 1 percent of the world’s coffee; Kraft, Nestlé and Procter & Gamble buy much greater proportions at much lower prices. Even so, Starbucks’ visible presence is much more apparent than any of these economically more powerful companies.

Although there are no immediate limits to growth, Starbucks depends on its ability to maintain good relationships, particularly with the local communities where it operates and the farming communities where it sources its coffee. Its ability to grow depends on the goodwill it can keep generating in the widest possible constituency. The conundrum for Starbucks is to grow big worldwide while retaining the soul of a small company based in Seattle.

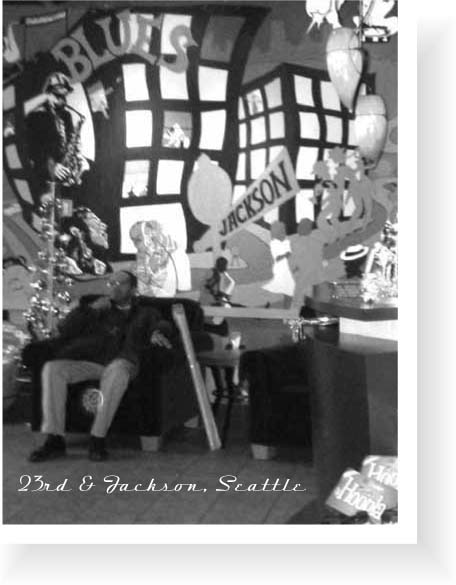

1971 Seattle

1972

1973

1974

1975

1976

1977

1978

1979

1980

1981

1982

1983

1984

1985

1986

1987 North-western USA, Canada

1988

1989

1990

1991 California

1992

1993 Washington DC

1994

1995 New York, United Airlines

1996 Japan, Singapore

1997 The Philippines

1998 Taiwan, Thailand, New Zealand, Malaysia, UK (England, Wales, Scotland)

1999 China, Kuwait, Korea, Lebanon

2000 Dubai, Qatar, Bahrain, Saudi Arabia, Australia

2001 Switzerland, Austria

2002 Oman, Indonesia, Germany, Spain, Puerto Rico, Mexico, Greece

2003 Turkey, Chile, Peru, Cyprus, Netherlands (European roasting plant)

2004 France, Costa Rica (Farmer support center)