I arranged to meet Neil McClelland at a Starbucks near his office in Victoria, London. I’ve known Neil for many years, in particular through his work as director of the National Literacy Trust. Ten years ago I had led the project to create the identity for this new charity that aimed to improve literacy skills. Today, the identity still looks fresh, and the National Literacy Trust is celebrating its most significant anniversary yet.

I wanted to talk to Neil because I had seen that Starbucks was promoting a “Book Drop” in association with the Trust. We talked for an hour over coffee, and I learned that Starbucks had been supporting the Trust financially for three years, funding one full-time member of staff. The main project involved Starbucks partners working as volunteers with libraries in 16 local authorities throughout the UK to bring mothers, carers and children into early, enjoyable contact with books and storytelling. Other projects, such as the Book Drop (encouraging customers to donate new books to children), had come along later as the partnership developed. Neil was in no doubt that Starbucks had delivered. His only frustration was that no one had heard of the literacy scheme. Starbucks had been adamant that the purpose of the scheme was to help mothers, children and the partners themselves, not to gain publicity.

I had first come across the link with the National Literacy Trust when I had seen the Christmas 2003 table card in Starbucks’ Covent Garden store. There were two main messages on its three sides. One side was about Starbucks’ Christmas Blend Whole Beans, a special seasonal blend of beans from Kenya and Guatemala. It was written in the language of the wine buff translated to coffee, with the heading “Special Reserve – Harvest 2003.” It read like this:

“Every year, Starbucks invites the world’s

coffee farmers to send us their finest beans

for our Special Reserve competition.

This year’s Starbucks Special Reserve Blend

combines two remarkable regions. From

Kenya’s equatorial highlands, we found a

coffee with an intense, citrusy taste, balanced

with delightful winey notes. And from

Guatemala’s Antigua and San Marcos regions,

we found coffees with a sparkling acidity and

a hint of cocoa in their profiles. . . .

In addition to the recognition, there is a

greater prize that comes with being named

a Starbucks Special Reserve coffee – help for

the farming communities that produced the

winning coffees.”

With after-knowledge I recognize the influence of Cecile Hudon, Seattle-based head of coffee education, in those “winey notes.” You might critique them as a piece of writing, but what is more interesting is the way they confront what has become the big issue facing Starbucks. Pressured by anti-globalization protesters, we need to ask: what is Starbucks doing for the Third World farmers it relies on? What has it been doing throughout its existence as a company? And is that enough?

The table card brings before us, when we turn it to read its other two sides, an extension of the debate. Starbucks needs to think of local as well as global communities. I say “needs,” but this is an imperative of relatively recent origin. Corporate social responsibility has been a live issue for companies for less than a decade. When British prime minister Edward Heath used the phrase “unacceptable face of capitalism” in the early 1970s, it took the corporate world by surprise; most business people at that time took their ethical responsibilities rather lightly. There was little thought that companies needed to do anything at all for local or global communities, except in a very paternalistic sense. Things have moved on, driven on the one hand by campaigners for environmental and social issues and, on the other, by the development of branding as a discipline.

What makes Starbucks produce a table card like this? It has very little to do with pushing up sales. It is almost entirely to do with Starbucks’ awareness that it is a brand and that it has to demonstrate the reality of that brand: its values, its beliefs, its purpose, beyond selling cups of coffee at a profit. So in this context we see the Starbucks Book Drop. The idea is to help a local child to read, and to encourage reading as an essential element in the learning process, by asking customers to donate new books for children. The store has a box where customers can put their donations. The scheme is run is association with the National Literacy Trust, and Starbucks provides funds and volunteers. It is a small initiative, modeled on a bigger scheme called “All books for children” organized by Starbucks in the US. Some 4,000 British children have benefited in the two years that the scheme has run. But this is only one of many initiatives by Starbucks to put something back into the community.

Starbucks does this to show that its brand values mean something to the company; they are not used merely to generate sales in some way. The aim is also to involve Starbucks’ own people in tangible projects that enable them to channel their own energies, interests and beliefs into good causes inside and outside working hours. By doing so they become more rounded people, more satisfied employees and more understanding ambassadors for the brand.

We should look again at the mission statement and its six principles. How do you demonstrate these through a working day of making coffee, collecting used crockery and wiping down tables? It is easier to do so if you see yourself as working in a framework that guides your behavior, and if you are also encouraged to play a deeper role in the community where you work.

This altruistic streak has always been present in the Starbucks brand. When the first shop opened in Seattle in 1971, there was a natural inclination to reach out to the needy in the neighborhood. But as the years have passed, Starbucks has given more and more official license to these philanthropic instincts. As understanding of the brand and its meaning has developed, Starbucks has realized its potential to do good not just by giving donations of money, as most corporations would approach it, but by harnessing the energy of its own people. In 2003, this translated into a new message on its US recruitment leaflets: “Create community.”

Starbucks’ understanding of its potential role and awareness of the need to engage with the deeper emotions of its workforce to encourage their commitment started with its successful creation as a public company in 1992. For Howard Schultz in particular, this raised questions about rewards, loyalty and sustaining the brand. His instinct, as with the healthcare provision and stock options, was to build the sense of a team and to set working life within a broader picture. So he became determined to focus more of his attention on local communities, and to encourage the partners in stores to channel their energies into good works.

In 1994, a natural event occurred that made the picture much bigger again. News broke that there had been a severe frost in Brazil, destroying much of the coffee crop. Starbucks bought none of its coffee from Brazil; the quality is generally not high enough, and most of it ends up in cans and jars of instant coffee. But the prospect of shortages meant that prices of coffee started to soar, the big coffee manufacturers immediately hiked their prices, and speculation drove commodity prices up. Starbucks already paid a premium for its coffee, but prices now doubled and were heading higher still.

Starbucks decided not to raise its coffee prices early but to protect customers in the hope that prices would stabilize. In the mean time, it would live off its supply of green beans – coffee bought in advance to ensure it had the quality it needed in sufficient quantity. Then Brazil suffered a second frost, causing further decimation to the crops. Coffee prices rose to 330 percent of the level three months earlier. This threw everything into turmoil. A further complication was the fact that Wall Street was now watching Starbucks’ every move. There were financial expectations to be met, and Wall Street was not inclined to philanthropic gestures.

Orin Smith had just been promoted from chief financial officer to president, and he took command. He decided that Starbucks should manage its way through the crisis, as far as possible cutting costs on backroom operations rather than passing on price rises to customers. The company had grown fast, without real planning, so there were savings to be made. People worked hard, under pressure; but the irresistible price rises to customers did not cover replacement costs of buying new coffee at high prices. A decision was made to buy a large quantity, effectively a year’s supply, of Colombian coffee beans. The price was high, but it might go higher. A risk was taken. If prices fell, Starbucks would be left with a lot of expensive coffee beans, but it would have to manage its way through without raising prices to customers to recover its position.

Then, soon after, prices started to come down. Everyone stuck by the decision, without recriminations. In the long run, the economy measures strengthened the company, though it would never have chosen to take them without the impetus of the coffee crisis. They ensured that when the next crisis came, Starbucks would be better placed and stronger. The crisis had also highlighted the plight of the coffee grower, and this had a long-lasting effect on the company.

For many years previously, Dave Olsen, who bought the coffee for Starbucks, had seen worrying signs of distress among the farmers and their crops. Much of the world’s coffee crop had been sold at below the price of production to the big coffee manufacturers. The farmers had to skimp, and bad farming practices had been introduced. Pruning was neglected; fertilizers were not bought. In many regions the coffee crops were weakening. Dave Olsen saw at first hand the effects on the farmers he knew. He was convinced that it was in Starbucks’ best interests to keep paying a premium price to its farmers for high-quality coffee, and to take other steps to protect them from crippling price reductions.

From this time on, Starbucks knew that its fifth principle – “Contribute positively to our communities and our environment” – could not be compromised. It had never merely been paid lip service, but now it became a driving principle for the brand. When it was exposed to the fluctuations of coffee prices, understood what that did to the farmers and at the same time felt the scrutiny of Wall Street, the effect was to temper the steel of the brand. Decisions had to be made, and those decisions drew on the principles of the brand.

Starbucks emerged a better company from the process. It could have saved itself millions by buying cheaper and poorer coffee. It could have abandoned the farmers who were supplying better quality at a higher price. Most of its customers might not even have noticed. But Starbucks would have noticed. Howard Schultz put it like this: “What, then, would keep us coming into work every day? Higher profits, at the cost of poorer quality? The best people would leave. Morale would fall. The mistake would eventually catch up with us. And the chase would be over.”

So now Starbucks decided that the principle of putting things back into its communities should go beyond encouragement. It entered the business model. Starbucks was convinced that not only was it right to have a conscience, but it needed to act on it. It started putting more efforts into developing programs: both local, around its stores, and in the coffee-growing regions with the farmers. It also decided that the benefits of doing these works were principally to do with its own partners and the communities themselves. The activities were never given PR objectives, so there was no extensive communication about them, partly because the overall thrust consisted of thousands of small initiatives rather than a single massive example of corporate benevolence. Because Starbucks wanted and needed to grow – not least now that it had to keep investors and Wall Street happy – it decided that it could succeed in the long term only by truly engaging with the emotions of its own people. So it set out to provide the environment for its partners to follow their own altruistic tendencies, to grow as people and to develop their skills in the process.

Much of this was building on what Starbucks had already been doing. As the executive who had the most contact with the coffee-growing regions, Dave Olsen had been building case studies and arguments for providing them with support. He established links with care, a humanitarian organization fighting global poverty, for which Starbucks has been one of the largest corporate supporters since 1991. The relationship started relatively small but has grown as Starbucks has grown, with the company contributing over $2 million to care’s programmes to fight poverty in coffee-growing communities. Projects to improve water systems, education and medical facilities have been funded in Nicaragua, Guatemala and many other countries.

Starbucks works directly with coffee growers

The Brazil frosts (which happened after the relationship with care had started) brought home that something more fundamental needed to be done. How could Starbucks tackle some of the basic causes of poverty in the coffee-growing regions? There were massive economic forces at work here; many other companies were shrugging their shoulders and saying “Not our problem.” Coffee is the world’s second most heavily traded commodity, after petroleum. Its economic power was apparent to the World Bank, which had encouraged many poor nations to move into coffee growing. This led to a world glut that soon started to drive prices down. As the farmers got less and less money, they were forced deeper into poverty. The only hope of salvation for many farmers is to produce the highest quality coffee that can be sold at a premium. Starbucks buys coffee in this premium range.

The large players in the coffee market have concentrated on buying coffee at the lowest prices on the commodity exchanges. A gap has opened between high-quality arabica coffee grown at altitude, and poorer-quality robusta grown on lower slopes. The figures show that 40 percent of the value of the world’s coffee is represented by 17 percent of its volume. Starbucks’ policy has been to secure long-term contracts with its coffee suppliers, establishing relationships in the mutual interest of the company and the farmers. So it pays prices that are substantially higher than the prevailing price of commodity-grade coffee. It negotiates prices that are independent of the commodity market, helping to provide stability and predictability for both buyer and sellers. The lessons of the Brazil frosts burned deep into the company’s psyche. Starbucks realized that it was in its own interest to ensure a sustainable supply of high-quality coffee.

To achieve that sustainable supply, Starbucks has pursued a number of strategies. These include building direct relationships with farms and cooperatives; negotiating long-term contracts; making affordable credit available to farmers; buying fair trade certified coffees, as well as certified organic and conservation coffees; and investing in health and educational projects that benefit the coffee-farming communities. Starbucks has also developed coffee-sourcing guidelines with Conservation International, an organization whose mission is to conserve the Earth’s natural resources and biodiversity. Under this framework, farmers who meet quality, environmental, social and economic criteria are rewarded with financial incentives and “preferred supplier” status. The arrangements are subject to independent audit.

Part of the strategy is to support fair trade, but Starbucks remains adamant that it selects its coffee first and foremost on the basis of quality. So it will not buy fair trade coffee that does not meet its quality standards. The reality is that the fair trade movement shares the same principles as Starbucks, helping to ensure that coffee farmers receive fair prices for their crops, but the fair trade system still accounts for less than 2 percent of the world’s coffee farmers. Fair trade is not the only way to ensure fair prices for farmers, but Starbucks supports it as one of its strategies. You can buy fair trade certified coffee in Starbucks in 19 countries, including the major markets of the US, Japan and the UK. Working with Oxfam, Starbucks is aiming to increase the supply of high-quality fair trade certified coffee from the 16,000 farmers who make up a large cooperative in Oaxaca, Mexico. When American activists organized a “National Call-In Day” against Starbucks, Transfair, the only certifier of fair trade products in the US, described the campaign as “particularly misguided and unfair because it ignores the company’s many important contributions to coffee farmers through fair trade and other programs.”

Starbucks undoubtedly feels picked on by protesters who ignore the facts. When it challenged one group “Why protest against us and not P&G?” the reply was “Because you care.” The anti-globalization protesters hurt Starbucks in a different way from, say, Nike, McDonald’s and Coca-Cola. Starbucks felt a real sense of injustice. It cared about the people who were part of its wider family: the coffee farmers and suppliers. It was hard to be attacked as a rapacious exploiter when it had always paid its partners higher than average wages, given them a valuable stake in the company, provided generous levels of health care, and taken the lead in supporting coffee farmers and their communities. Starbucks had put its own people at the center of its brand in a way that the protesters’ other targets had not. And the sympathies of many in Starbucks, coming from liberal, laidback Seattle, were probably close to the protesters’ views. When put together with Starbucks’ awareness of the European coffee house tradition to provide places for debate and radical thinking, it all raises the rather ironic picture of anti-globalization protesters gathering in Starbucks stores around the world to plan their next protest.

Without doubt Starbucks felt discouraged by protests and acts of vandalism against its stores. Many, including Howard Schultz, took the attacks personally and felt misunderstood and misrepresented. Starbucks’ response has simply been to plough on, continuing to build its support for coffee-farming communities and the neighborhoods where it locates its stores. Despite all the protests and bad publicity, it remains more committed than ever to good works, though there has been no public relations blitz to publicize them. Howard Schultz put it like this: “We can both do well and do good. We can be extremely profitable and competitive with a highly regarded brand, and also be respected for treating our people well. In the end, it’s not only possible to do both, but you can’t really do one without the other.”

For those who find sheer altruism hard to imagine, there is a compelling business case that all brands should note. We all have a vested interest in sustainability, even if we don’t recognize it. Starbucks does. Early in 2004, it announced that it was establishing the Starbucks Coffee Agronomy Company in Costa Rica. The new venture will have a team of agronomists, quality specialists and sustainability experts to ensure the future availability of high-quality sustainable coffee from Central America. It forms part of Starbucks’ effort to get beyond the exporter direct to the farmer, and was prompted by concern that farming practices and husbandry have been critically damaged by years of low prices. Starbucks is acting out of self-interest: it fears that in a few years’ time there might not be enough quality coffee available to sustain its projected growth rate. But self-interest and other people’s interest can coincide.

Indeed, this is the notion behind Starbucks’ practice of encouraging its partners to work in their local communities to support nonprofit organizations. If you understand this principle, you will understand much of the success of the brand. Satisfaction ratings among staff have placed Starbucks consistently in the top 10 percent of US employers. Material issues – pay and benefits – will account for much of this, but the efforts to encourage volunteering also count. People enjoy working with a company that they perceive as having a soul.

So Starbucks regards support for local communities as an investment: part of its business strategy rather than a series of charitable donations. But even at that level, the charitable donations add up to a major contribution. The way they are organized is characteristic: instead of having the board decide which charities to support each year, Starbucks gets its partners to nominate their favorite causes. The partners give their time and money, and the company supports them with money, materials and encouragement. In the US, two umbrella schemes support volunteering and the championing of nonprofit organizations by partners. The first, “Make your Mark,” matches a $10 contribution for each volunteer hour worked by a partner (or by the partner’s family and friends) for a cause of their choice up to a maximum of $1,000. In 2002, 68,000 hours of volunteer time were matched by a $433,000 Starbucks donation. The second scheme, “Choose to give,” matches Starbucks funding to an individual partner’s philanthropy. The partner chooses the charity and makes a donation; Starbucks donates the same amount and absorbs all the fees and administrative costs. In two years, donations by partners and by Starbucks have exceeded $1 million.

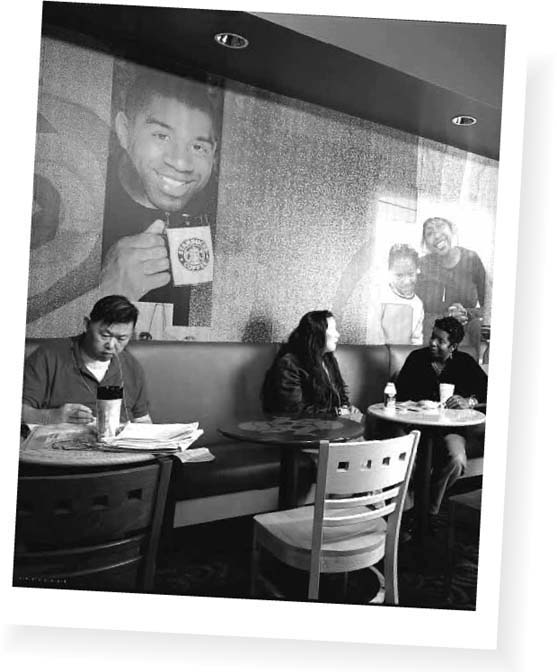

There are numerous other charitable initiatives, most of which originate at the level of the local store. But there are two particular corporate initiatives that tell us something about the Starbucks brand. The first is Urban Coffee Opportunities, a joint venture between Starbucks and the basketball star Magic Johnson. The aim is to open Starbucks stores in deprived, ethnically diverse neighborhoods such as Harlem in New York. Most of these neighborhoods have been neglected by business because of their poverty and social problems. When Starbucks enters the community, it lights a beacon for other retailers. The Starbucks stores provide employment and stimulate other business activities that would otherwise stay away. There were 35 of these stores operating in 10 states in 2003.

The second example of corporate philanthropy is the Starbucks Foundation, established by Howard Schultz in 1997 to provide funds for literacy programs. The Foundation encourages volunteering, and provided $1.7 million to schemes in 2002. It has given grants of $6 million to 625 nonprofit literacy causes since it was set up; the UK National Literacy Trust venture described earlier in the chapter was one of its beneficiaries. One of its most striking activities is Jumpstart, which matches volunteer college students with preschool infants from low-income communities. Together, and with support from Starbucks partners, they build children’s early language, literacy and social skills.

Magic Johnson

Part of this is no doubt fuelled by Howard Schultz’s origins in Brooklyn. He experienced first-hand what it means to grow up in a neighborhood that has been deprived of economic sustenance (and the hope that it brings). Even so, American corporate history is full of people who make good despite the economic disadvantages of their upbringing, yet very few of them feel the same need to give something back to the kinds of neighborhood from which they came.

The real power of Starbucks’ approach is that unlike the paternalistic business benefactors of the past, Starbucks does not simply dish out money and then stand back. It does give money, but it also encourages its partners to be active in bringing about beneficial change in their communities. This creates an energetic network, a dynamic movement that produces effects beyond the reach of purely financial donations. Starbucks realizes that, for good to come about, good people need to do good.

And by doing so, they will each add depth and richness to the Starbucks brand.