4

WOMEN IN SOFTBALL

AND BASEBALL

Mexican American women have a long, rich history in softball and baseball. The game allowed women to assert autonomy, cultural pride, and athleticism while maintaining their femininity. Sports tested socially constructed notions of femininity while slowing shifting traditional family structure. Teams emerged within school playgrounds, mutual-aid societies, religious organizations, community parks, and local businesses. Participation on the diamond mirrored social, cultural, political, and economic patterns across the nation.

In 1910, the Mexican Revolution pushed Mexican families into the United States. This shaped the composition of the nation’s population, labor force, politics, and emerging communities. By 1915, efforts commenced to Americanize Mexican immigrants. The focus became women and children. Social reformers employed softball and baseball as a tool for Americanization. Nevertheless, sports elevated community and cultural pride, evident through teams’ bilingual names and recognition of barrios, as well as neighborhood cooperative spirit.

By the 1930s, the Great Depression hit America with vengeance. Sadly, minorities bore the brunt of the economic frustration. The government enacted the Repatriation Act, which removed an estimated one million people of Mexican descent. In the 1940s, de facto segregation limited access to jobs, public amenities, housing, schools, movie theaters, and cemeteries. Despite racial segregation, Mexicans American led unions and communities flourished, sponsoring various softball and baseball teams.

As males enlisted in the service, it left a void on and off the field. Consequently, World War II cultivated more women’s softball teams. A shortage of employees in the defense manufacturing industry pushed women into these jobs, which offered higher pay. Between 1943 and 1954, the All-American Girls Professional Baseball League (AAGPBL) recruited women to join its league, 11 of them Latinas. It replaced several minor-league teams disbanded due to the war. In 1972, Title IX broke down barriers in women’s sports, opening doors to collegiate sports and scholarships. Overall, this chapter plays tribute to the courageous women who served as pioneers in softball and baseball, paving the way for future generations.

Stella Ayala Encinas stands side-byside with two players from the Juvenile baseball team of Claremont. She played for the Questionettes of Chino. She later married Maury Encinas and raised the next generation of female players. Her brother, Congressman Ruben Ayala, represented the western San Bernardino County cities of Chino, Colton, Fontana, Ontario, and Rialto, and Pomona in Los Angeles County. He became the first elected mayor of Chino and served the California State Senate from 1974 to 1998. (Courtesy of the Encinas family.)

Stella and Maury Encinas, with other spectators, sit and watch a Juveniles game. Restricted from participating on whites-only teams as well as playing on official park grounds, Mexican American players established their own teams and venues. Discriminatory practices pressed teams to play in vacant lots and empty fields. In some cases, those who owned vehicles surrounded the makeshift diamonds, creating bleachers. Teams, family members, and communities rallied together to fundraise for equipment and uniforms. (Courtesy of the Encinas family.)

The Questionettes of Chino played in the Pomona Valley Women’s Softball League and became the undefeated champion team. They remained unbeatable during a six-game series. Art Wagner, chief of the Chino Fire Department, managed the all-girls team. The team included members such as Lila Kinzey, Stella Ayala, Mary Jane Robles, Margaret English, Frances Dipoli, Betty Dixon, Harriet Decker, Jean Groomes, Elaine Maxey, Tommy Kulpenski, Peggy Webster, and Emma Boyen. (Courtesy of the Encinas family.)

From 1964 to 1967, Stella Briones participated in women’s fast-pitch softball in Chino, California. Her father, Amado, coached her and the team. As migrant farm workers, the Briones family traveled throughout the Southwest following the harvest. By 1924, the family settled in Southern California. For some migrant workers, sports functioned as a unifying factor when employed in company towns, farms, and packinghouses. The patriarch of the family, Amado passed down the love for the sport to future generations. (Courtesy of Chuck Briones.)

In the 1930s, Virginia García Elías played softball for the Girls’ Athletic Association (GAA) at Valencia High School in Placentia, California. Founded in 1922, the organization spread throughout the United States recognizing female athleticism. It sought to promote healthy recreations while opening athletic fields and gymnasiums for females. The various sports of interest included baseball, basketball, bowling, hiking, horseback riding, swimming, and tennis. Virginia, along with Pedro, her husband, passed the love for the sport to their children. (Courtesy of Estella Elías Acosta.)

Growing up in Pomona during the 1950s, Estella Elías Acosta and younger sister, Lydia Elías Mulkey, enjoyed playing ball with local youth. The neighborhood youth shared equipment such as bats, balls, and gloves. They played on an improvised field adjacent to the Elías home that their father, Pedro, kept up. Although the games were informal, they became instrumental in the development of their softball skills and sportsmanship. In 1962, the Elías sisters participated on the Pomona Catholic High softball team. (Courtesy of Estella Elías Acosta.)

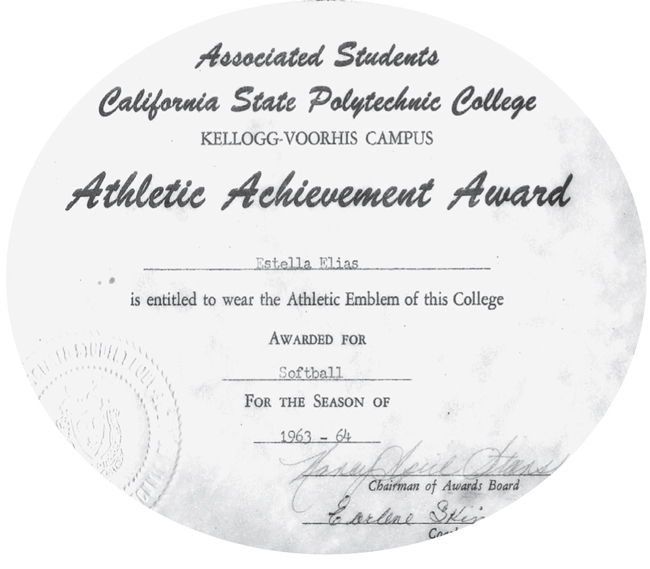

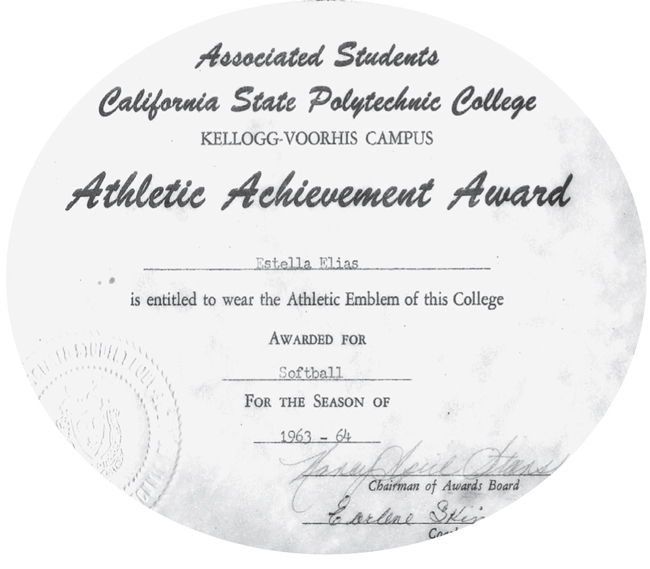

In 1963, Estella Elías Acosta attended Cal Poly Pomona, only two years after the first women were admitted into the institution. She earned recognition in softball with a certificate. She, along the other team members, set the foundation for official women’s sports teams at Cal Poly Pomona, which grew in the 1970s. This shift emerged with the passing of Title IX, which protected against discrimination based on sex for education programs and activities that received federal financial assistance. (Courtesy of Estella Elías Acosta.)

The 1960s Chino-based softball team was comprised largely of family members, a common practice among teams. Represented are, from left to right, (first row) Patty Encinas, Marlyne Encinas, Valentina Ruiz, Debbie Allen, and Patti Encinas; (second row) Nancy Encinas, Jernell Encinas, Darlene Allen, Dale Peevey (manager), Bonnie Encinas, Peggy Peevey, and Margaret Padilla. In the 1970s, many of the girls also played for the Van Dyk’s Mod-Maids of Chino, winning 13 of 15 games and earning a championship. (Courtesy of Patricia Encinas García.)

Betty Hermosillo Reynoso pitched for the Claremont Panthers. She was an awesome fastball pitcher. Lola Hermosillo, Vivian Aguilera, Virginia Hermosillo, Luz Guerrero, Lupe Guerrero, Isabela Martínez, and Mary Gutiérrez made the team. The team represented the tenacious spirit of Mexican Americans, relegated to the outskirts of town in barrios such as Árbol Verde that bordered the cities of Montclair and Upland. These enclaves promoted culture pride and community sustenance through sports, patriotic celebrations, and religious events, as well as dances. (Courtesy of Ronnie Reynoso.)

The Señoritas of Glendale traveled throughout the Los Angeles area playing against teams of different ethnic backgrounds. They competed with teams such the Masquerettes and George Von Elm’s Birdies. The Los Angeles Times highlighted the team on April 28, 1936, with a caption that reads, “Snappy Spanish Señoritas Play Pelota Muy Buena.” The team displayed its talents at the 1936 championship for the American Softball Association at Loyola Stadium in Los Angeles. (Courtesy of Vincent Pérez.)

The 1951 champions of Belvedere Park in East Los Angeles, the Colombians, played against the Rosewood Park Royalties, Bell Garden County Park Parkettes, and Laguna Cupids. Trophies went to captain Lupe Díaz, Alma Galindo, Carmen Carrillo, Cherie Payne, Lucy Amparano, Ophelia Carrillo, Margaret Castañón, Natalie Amparano, Rose Marie Rice, Sally González, and Stella Sánchez. The street attire and hairdos suggest the effort to maintain a feminine presence, despite their athletic talent. (Courtesy of Alma Gallindo.)

Della (left) and her sister Anita Salazar are in front of Bridges Auditorium at Pomona College in 1943. Both sisters along with a third sister, Connie, played for the Claremont Braves, a Mexican American women’s softball team, from 1943 through 1946. Connie and Della pitched, while Anita played third base. They played against other Mexican American women’s teams from Pomona, La Verne, San Dimas, and another team from Claremont. The coach for the Braves was Joe “Chino” Torrez, an outstanding player in the Pomona Valley. (Courtesy of Anita Salazar Elias.)

Connie Salazar pitched for the Claremont Braves along with her sister Della. Other players were their sister Anita, Lola Contreras, Cruz Moreno, Rosa Melendres, Helen and Mary Parilla, Rosa Torres, Gloria Gonzales, and Mary Aceves. The Salazar sisters had several brothers who served in the military, including three who fought in World War II: Ruben, Manuel, and Ausencion. Ausencion, also known as Chone, was killed in the Pacific. It is believed he died on the island of Cebu. (Courtesy of Anita Salazar Elias.)

Dorothy Romero of the Rock-Ettes poses amid an open field. Growing up in the 1940s, her family lived on a farm on Nance Road in Santa Barbara. The region possessed a wide array of ethnic groups, including Filipinos, Italians, Japanese, Mexicans, Portuguese, and Swiss. The Rock-Ettes reflected the diversity. The area’s rich farmlands produced jobs on the field and in packinghouses. For many teams, Sunday became game day. Her team dominated the league and earned a championship in 1945. The Guadalupe Rotary Club sponsored the team. (Courtesy of Dorothy Romero Oliveria.)

The Catalina Island Firebells played during the early 1970s. The Los Angeles County Fire Station 55 sponsored the team, hence the team name. A number of Mexican Americans played on the team, including Maui Saucedo Hernández (no. 53), Vickie Hernández (no. 9), Stella Hernández Herrington (no. 7), Gayle Saldaña (second row, fourth from left), Rose Hernández Engel (no. 1), and Cookie Saldaña (no. 6). Anglo teams often invited Mexican American women to join the teams because of their incredible talent and teamwork. (Courtesy of Theresa McDowell.)

In the early 1970s, a local restaurant sponsored the team El Galleon. The team was comprised of a mixture of women including pitcher Chatta Saldaña Ponce, whose father worked for the Wrigleys as a gardener. Maria Hernández Soto, who also played, was the daughter of Lipe and Maui Hernández, players themselves; she effectively blocked the plate, knocking people down. Many of the women grew up on Tremont Street, one of four Mexican barrios on Catalina Island. (Courtesy of Theresa McDowell.)

On August 18, 1940, the Sacramento Union highlighted six teams from the Second Division Girls’ Municipal Softball League. Mexican American women made up the Rio Grande softball team. The division included teams such as the Woolworths, Garlicks, Telephone Company, and Pioneer Venetian Blinds. Team members included manager Buzz Dávila, Linda Sánchez, Jennie Dávila, Mary Dávila, Muzzie Valenzuela, Teresa Rojas, Josephine “Josie” Rojas, Babe Cervantes, Lily López, Margret Rojas, Adeline Huerta, Chelo Sánchez, and García Carrillo. (Courtesy of the Cervantes family.)

Rachel Cervantes-Wallin (second row, third from left) played for the Catholic Youth Organization team in Sacramento around 1956. She played basketball, softball, and volleyball for St. Joseph Grammar School and Bishop Armstrong High School. At the age of 12, she played for the Sacramento’s Women’s Nite Softball League. At Sacramento City College, Rachel played basketball, softball, field hockey, and was the top player on the tennis team. She has coached several sports for years. She was a teacher, counselor, and a principal in the Sacramento Unified School District. (Courtesy of Rachel Cervantes-Wallin.)

Arizona Hall of Famer Grace Pellón started to play softball as a preteen. Her father, Charlie, played ball himself. She played on various teams during her lengthy softball career. She passed on the love for the sport to her children and grandchildren. Her daughter, Norma Gallegos, earned a scholarship to play softball at the University of Arizona in Tucson. She made history as part of the 1974 team, Arizona’s first Women’s College World Series team. (Courtesy of Darcy Quinlan Meyer.)

In 1947, three thousand spectators showed up to raise funds for Joaquin Carranza, a boy who lost his legs in a train accident in Tucson, Arizona. The All-Stars, an all-girls team managed by Grace Pellón, played Charlie Pellón’s Old Stars, men over 45 from Southern Pacific Railroad. The bout took place at Twenty-second Street Park, tickets sold for 25¢, and the umpire dressed like a clown. The All-Stars won the game, 27-14. The Coció-Estrada American Legion Post turned over all proceeds to his family. (Courtesy of Darcy Quinlan Meyer.)

In the 1880s, Barelas, New Mexico, began to change as the Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe Railroad ran though the mid–Rio Grande Valley. This reshaped the landscape and disrupted the agricultural economy. However, sports remained constant, serving as an avenue for social and family events. Baseball coach Vince Aragón worked with neighborhood youngsters for nearly 50 years. The 1940s girls baseball team outside on the school playground is a good example. (Courtesy of the National Hispanic Cultural Center.)

This young all-girls softball team from New Mexico displays their bats and street attire on the steps of the school grounds. Sports at an early age prompted the development of character among youngsters while encouraging community involvement and pride among adults. Girls in sports needed to balance traditional ideals of a proper young woman and athletic talent. These ideals presented themselves in team names, uniforms, and kinships with teams, as well as sponsors. (Courtesy of the National Hispanic Cultural Center.)

In the 1950s, the San Antonio Angels baseball team was sponsored by the Owl Bar and Café in Socorro County, New Mexico. Members shown included, from left to right, (first row) Mabel Ramírez, Isabel Montoya, Rowena Eaton Baca, and Celia Martines; (second row) Flora Chávez, Dee Chávez (coach), and Rosa Lucero; (third row) Lupe Montoya, Christy Chávez, Petra Rivera, and Josie Padilla. The team practiced consistently, playing teams nearby and as far as 50 miles. (Courtesy of Rowena Baca.)

Las Gallinas often traveled with men’s teams, particularly Los Gallos (the Roosters) of East Chicago, Indiana. Some games became double-headers; the women played in the morning and the men game played later in the day. Players Alice (left) and Bertha Zaragoza displayed their talents on the field. Some of the female players were talented enough to play side-by-side with their male counterparts. Parents supported their daughters, but often brothers and other family members watched over them during practice and games. (Courtesy of Señoras of Yesteryear.)

In the 1930s, women’s softball teams sprouted throughout the Midwest. Mexican American women were no different; Pitcher Petra González Segovia of Las Gallinas (the Hens) of East Chicago, Indiana, is a prime example. The team, greatly supported by the community, took collections from their enthusiastic fans to purchase new green satin uniforms, which they proudly wore during games. Men mostly coached and managed the women’s teams. These men proudly become involved and were respected by parents as well as the community. (Courtesy of Señoras of Yesteryear.)

Florence V. Porras and other members of Las Gallinas became community attractions. The team’s popularity prompted organizers to begin a junior team called Las Gallinas Chicks. During World War II, the dynamics of women’s role in society changed. As men enlisted in the service, defense manufacturing plants called on women to fill the labor shortage, giving rise to the iconic “Rosie the Riveter.” Their younger sisters would play for the 1949 girls softball team led by the Young Christian Workers (YCW). (Courtesy of Señoras of Yesteryear.)

The 1949 girls softball team of East Chicago included, from left to right, (first row) Louis Vásquez, Minnie Patino, Carmen Torres, Alice Vásquez, Patsy Godoy, and Frank Villarreal; (second row) Stanley Ríos, Cecilia Buitron, Eleanor Vásquez, Mary Torres, Sally Bedoy, Alice Patino, and Charley Ursa. Their best and youngest player, Cecilia Buitron, helped the team to many wins. The team played behind Field School, behind the Wallace coal yard, or at an empty lot on Guthrie Street along the Pennsylvania tracks. (Courtesy of Lupe Aguirre.)

The Quad-City Girls All-Star Team of 1950 played at Douglas Park in Rock Island, Illinois. The team was comprised of elite softball players from the Eagles, Glicks, Servus Rubber, and Pepsi. The team featured Margaret Macias (first row, first from the left) from the Eagle’s Market Superettes. The year prior, she and her sister, Juanita Mary Conchola, a member of the Women Army Corps at Randolph Air Force Base, played in the National Softball Congress World Championships, hosted in Colorado. (Courtesy of Dar Hanssen.)

Margaret Villa Cryan of the Kenosha Comets was one of 11 Latinas that played for the All-American Girls Professional Baseball League (AAGPBL). Philip W. Wrigley, owner of the Chicago Cubs and the famed chewing gum, created the league, which began in 1943 and disbanded in 1954. Margaret played for the team from 1946 to 1950, playing second base and shortstop but mainly catcher. The league hit its peak in 1948. Teams formed in Midwestern cities, where there was a lack of major-league teams. (Courtesy of Margaret Villa Cryan.)

The North End Wichita girls’ teams of the 1940s reflect the growing popularity of softball in the Midwest among Mexican Americans. Pictured from left to right are (first row) Cora ?, Victoria Díaz, Carmen Alfaro, and Maggie Gallardo; (second row) Alice Gallardo, Marcella Díaz, Eva Díaz, and Yolanda Castro. Family members often played together; it served as an indirect chaperone system. During dates, dances, and social events, parents utilized chaperones in order to monitor their daughters’ moral behavior. (Courtesy of Ray Olais.)