Chapter Seven

ADOPTED BY WOLVES

1.

Kipling’s first achievement in The Jungle Book is to establish, from its opening words, a believable family of wolves, neither overly anthropomorphic nor too alien and wild:

It was seven o’clock of a very warm evening in the Seeonee hills when Father Wolf woke up from his day’s rest, scratched himself, yawned, and spread out his paws one after the other to get rid of the sleepy feeling in their tips. Mother Wolf lay with her big gray nose dropped across her four tumbling, squealing cubs, and the moon shone into the mouth of the cave where they all lived. “Augrh!” said Father Wolf. “It is time to hunt again.”

When Kipling specifies how Father Wolf spreads out his paws, one after the other, to get rid of the sleepy feeling in their tips, he turns us all into wolves.

Into this cozy domestic scene a tiny stranger intrudes. Father Wolf identifies the visitor as “a man’s cub,” separated from his terrified parents by the marauding tiger, Shere Khan. Mother Wolf, meanwhile, is nursing her own cubs. “How little! How naked, and—how bold!” she remarks. Her last observation coincides with the man cub’s efforts to muscle his way among the wolf cubs and get some milk for himself. “The baby was pushing his way between the cubs to get close to the warm hide,” Kipling writes. “Ahai!” says Mother Wolf. “He is taking his meal with the others. . . . Now, was there ever a wolf that could boast of a man’s cub among her children?” This is meant as a rhetorical question, but Father Wolf answers it anyway: “I have heard now and again of such a thing,” he says, “but never in our Pack or in my time.”

Most readers (or viewers of the classic 1967 Disney adaptation) are familiar with Mowgli’s progress among his wolf brothers; his tutelage under the kindly bear, Baloo, as he learns the precepts of the Law of the Jungle; the teachings of more severe panther, Bagheera, who was born in captivity and knows the ways of men; his ambiguous relations with the deadly snake, Kaa; his fight-to-the-death hostility toward the tiger, Shere Khan. These are all part of our mythology, as enduring as Huck Finn or Tarzan, that latter-day Mowgli. We come to accept Mowgli’s wolf family as his real family, his primary allegiance. “I have obeyed the Law of the Jungle, and there is no wolf of ours from whose paws I have not pulled a thorn,” Mowgli says. “Surely they are my brothers!” We allow ourselves to be outraged, later in the book, when he is kidnapped by a band of monkeys, as though wolves are closer in nature to humans than monkeys are. We might contrast this upbringing with that of Tarzan, who is adopted by humanoid apes, a much closer link in the evolutionary chain, as Edgar Rice Burroughs repeatedly reminds us.

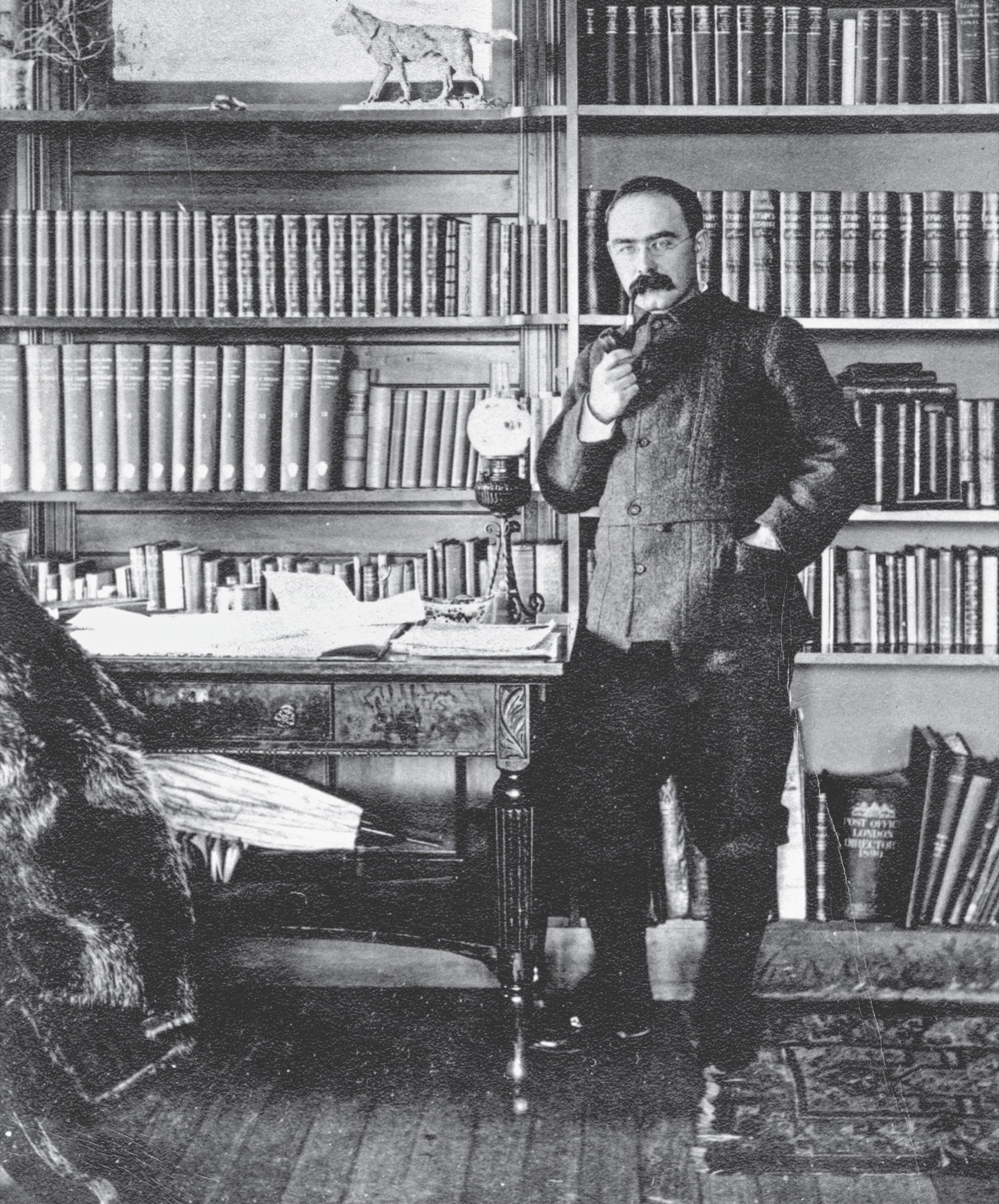

Kipling in his Naulakha study, with a statuette of Mowgli’s wolf brother, a gift of Joel Chandler Harris.

No moment in The Jungle Book is more poignant than Mowgli’s brief and ambivalent sojourn in the home of his presumed birth mother, Messua, a kindly rural villager who doesn’t know quite what to do—like many a mother since—when her teenage son wanders back into her life for a few weeks. It has become clear, to Mowgli and to us, that he will not be able to choose a mate from among the wolves or the monkeys. His only real future, even in a book as fantastical as this one, is with his own kind. Mowgli, who has grown up in the forest, is uncomfortable in his birth mother’s hut, which feels like a trap to him; she is uncomfortable outside it, where wolves and tigers roam. One thing she does do, however, is give the child milk to drink, as though her nursing, interrupted so many years earlier, could now be resumed without complication. Suddenly, at this very moment, Mowgli feels something touch his foot. “Mother,” says Mowgli, “what dost thou here?” It is Mother Wolf, his adoptive mother, licking his foot. “I have a desire to see that woman who gave thee milk,” says Mother Wolf. Then she growls, possessively, “I gave thee thy first milk!”

Kipling often explored the imaginative possibilities of his stories by working out alternatives in his poems. In a poem written in Brattleboro around 1893, and included as an epigraph in early editions of The Jungle Book, he staged an encounter between a human birth mother and her wayward son, who is drawn to the night world of wolves. The poem is called “The Only Son,” and its opening lines describe a mother’s fear about noises in the night outside: “She dropped the bar, she shot the bolt, she fed the fire anew, / For she heard a whimper under the sill and a great grey paw came through.”

Having secured the door, she does nothing more, but her son has an unsettling dream, related to that great gray paw: “Now was I born of womankind and laid in a mother’s breast? / For I have dreamed of a shaggy hide whereon I went to rest.” After a few more lines in this questioning vein, the Only Son asks his mother to unbar the door since, as he says, “I must out and see / If those are wolves that wait outside or my own kin to me!” The poem concludes as it began, from the mother’s point of view: “She loosed the bar, she slid the bolt, she opened the door anon, / And a grey bitch-wolf came out of the dark and fawned on the Only Son!” Kipling has led us into another myth altogether, the familiar nightmare figure of the werewolf. The poem is a reminder of how original the treatment of Mowgli is by contrast, in which the wolves are a comforting, intimate family, a refuge from human turmoil and not, as in the poem, an intensification of it.

2.

Kipling’s originality is even more striking when his account of Mowgli’s adoption by wolves is contrasted with its Indian sources. He alludes to these accounts when Father Wolf tells Mother Wolf that he has heard of wolf adoptions, “but never in our Pack.” Kipling’s father had a particular interest in such stories. In his encyclopedic book Beast and Man in India, published in 1891, Lockwood Kipling wrote, “India is probably the cradle of wolf-child stories, which are here universally believed and supported by a cloud of testimony.” One source that Kipling drew on for his Mowgli narrative is titled “An Account of Wolves Nurturing Children in Their Dens,” written by W. H. Sleeman, a British official. Sleeman is best known today for his suppression of a secret criminal gang known as the Thuggee (from which the word “thug” is derived); Mark Twain was enchanted by Sleeman’s account of his successful campaign. In 1849–50, however, Sleeman traveled throughout the Kingdom of Oude for the purpose of recommending measures to improve the region and the plight of its people. He was also supposed to provide evidence in support of the recent annexation of Oude by the British East India Company. During his travels, he claims to have heard many reports of wolves carrying off native children.

The six stories Sleeman reports have certain features in common. The children carried off by wolves are always native children, never British. They are always rescued by government officials, never by villagers. In those cases where parents recognize their children after their rescue, things do not go well; the parents give up the children for adoption or the children die. The behavior of the feral children, after their rescue from the dens of wolves, is remarkably similar in the six accounts. They have calluses on their elbows and knees from crawling around on all fours. They prefer raw to cooked meat. They tolerate the company of dogs when feeding. They are incapable of learning human language. They die young.

Sleeman appears to have thought that such consistency added to the credibility of the stories, but the repetitive details suggest instead their formulaic nature. All of the reports come from the same period, from about 1842 to 1848, with a cluster of three or four—Sleeman is not precise—dating from 1843, apparently a banner year for wolf adoptions. Such a concentration of stories in a particular place and time would suggest either an epidemic of wolf adoptions, as though the wolves had suddenly developed an appetite for raising human children rather than eating them, or a mass hysteria among villagers. Sleeman argues, however, that the Hindu villagers made a profit from their transactions with wolves, essentially trading their children for money. “It is remarkable that they very seldom catch Wolves, though they know all their dens, and could easily dig them out as they dig out other animals,” he writes. “This is supposed to arise from the profit which they make by the gold and silver bracelets, necklaces, and other ornaments, which are worn by the children, whom the Wolves carry to their dens and devour, and are left at the entrance of these dens.” He concludes with the damning observation, “In every part of India a great number of children are every day murdered for the sake of their ornaments.”

One might think that this peculiar analysis would help explain why so many native children are eaten by wolves rather than nurtured by them. But for Sleeman, the devouring and the nurturing are part of the same pathology, namely that native Hindus, in his view, simply don’t care very much for their children. The characterization of Indian peasantry that he is at pains to establish is that of careless and apathetic parents distracted by their work in the fields, as their children meanwhile are “carried off” by wolves. When the feral children are returned to them, the parents, appalled by their grunts and nasty smells, proceed to place the children, doubly lost to their parents, in charity care. The responsible parties in these stories are never the villagers, with their benighted family values, but rather the British officials and those employed by them. The need for European paternalism is triumphantly demonstrated at every turn. The local Hindus must be taught to value their children more than the gold bracelets on their wrists.

Kipling departed from these Indian sources in several key ways. He chose a native child for his hero, rather than a British official or child, and he portrayed Mowgli’s native birth mother as a sympathetic figure. Kipling went further, in portraying the adoptive family of wolves with equal sympathy. One might compare, in this regard, the Mowgli stories with Edgar Rice Burroughs’s eugenic fantasy Tarzan of the Apes, for which Burroughs borrowed many details from The Jungle Book, including a godlike hero of superhuman strength, agility, and physical beauty raised in the wild by ferocious animals. Burroughs departs from Kipling in his insistence that Tarzan’s birth parents are English nobility, Lord and Lady Greystoke, and that what Tarzan learns about proper behavior does not come from the great apes who raise him but rather from the books his parents have left behind. Mowgli, by contrast, is adopted by friendly wolves that also happen to be model parents. He grows up not with calluses on his knees and elbows, cowering in the shadows like Sleeman’s unfortunate waifs, but as an energetic and sensitive leader, powerful in mind and body, who can kill a tiger, make complicated moral choices, and right the wrongs in both human and animal communities.

3.

If Kipling relied in part on Indian sources for his tale of Mowgli among the wolves, he also drew on his Vermont surroundings, especially his conviction that he was living in a lawless jungle. “Kipling never quite outgrew his first impression that every American citizen carried concealed weapons of war,” his friend Molly Cabot recalled. He had witnessed a murder in a San Francisco gambling den. He had watched an American woman enjoying the carnage of a Chicago slaughterhouse. Such experiences had left him convinced that violence was at the molten core of American life. As though to stave off the chaos that surrounded them, he and Carrie dressed each evening for dinner, much to the amusement of their more informal neighbors. Kipling considered himself, as a well-informed outsider, uniquely qualified to interpret this bloodthirsty society. He was “the only man living,” he insisted to Cabot, “who could write The Great American Novel.”

Kipling believed, furthermore, that America was “the place in which to create.” His father summarized Rudyard’s expansive view: “There is undoubtedly a freer outlook from America for the man who prefers to think for himself than from London.” Kipling gleaned most of his useful information about his new surroundings from Cabot. Lively, sophisticated, and well read, she was a longtime friend of the Balestier family, long assumed to be Wolcott’s future wife. She had never married, living alone in the handsome, upright house inherited from her father in the fashionable neighborhood of terraces near the Connecticut River, on the northern edge of Brattleboro. A dedicated antiquarian who wrote two volumes about her native city, Cabot was a steady fund of anecdotes and gossip for Kipling, as he eagerly sought out material for his own writing.

A passionate reader of American literature, high and low, Kipling was acutely aware of contemporary writing about ordinary lives lived in New England, the so-called “local color” school, which consisted primarily of women writers writing about women’s subjects. Kipling was contemplating a volume of “Country Sketches,” for which Cabot supplied photographs. These would be about women, since so many of the men had fled the farms and villages of Vermont for better prospects elsewhere. “It would be hard to exaggerate the loneliness and sterility of life on the farms,” he wrote. “What might have become characters, powers, and attributes perverted themselves in that desolation as cankered trees throw out branches akimbo, and strange faiths and cruelties, born of solitude to the edge of insanity, flourished like lichen on sick bark.” These were the resilient lives described by local-color masters like Mary Wilkins (later Freeman), who lived in Brattleboro, and Sarah Orne Jewett, based in Boston and Maine. “It has been said that the New England stories are cramped and narrow,” Kipling wrote in their staunch defense. “Even a far-off view of the iron-bound life whence they are drawn justifies the author. You can carve a nut in a thousand different ways by reason of the hardness of the shell.”

Kipling’s view might be called the netsuke theory of local-color writing: the harder the conditions, the more possibilities in describing them. One of the first guests the Kiplings welcomed to Bliss Cottage was Mary Wilkins. “I invite Miss Wilkins to come to us today for tiffin,” Carrie wrote in her diary on October 11, 1892. With its spare furniture and bare floors, their tiny cottage could have been the setting for a typical Wilkins story of deprivation. Wilkins’s sharp-edged stories about tough-minded women in villages and farms, such as “A New England Nun” and “A Poetess,” appealed to Kipling, who once described a woman he had met in the neighboring village of Putney as “the best subject Mary Wilkins never wrote about.”

And yet, perhaps out of respect for what writers like Wilkins and Jewett (whom he also befriended) had already accomplished, Kipling ultimately shied away from trying his hand at the dialect and the dilemmas of the local townsfolk. He wrote one fanciful story about personified locomotives in the Brattleboro railroad shed and another about loyal workhorses rejecting a new arrival who wants to organize them for a labor strike. Instead, he found his imagination fully engaged by a very different kind of local color—far beyond the villages, beyond the farms. “Beyond this desolation are woods where the bear and the deer still find peace,” Kipling wrote, “and sometimes even the beaver forgets that he is persecuted and dares to build his lodge.”

4.

Most persecuted of all the woodland animals, however, was the wolf. And it was the adventures of a family of wolves that began to take shape in Kipling’s imagination amid the wolf-less hills of Vermont. Abundant timber, as Molly Cabot explained, had first attracted European adventurers and settlers to the banks of the Connecticut River: virgin forests and the abundant wild game that lived among them. Great logs of white pine, destined for ships in the British navy, were floated down the river from Vermont as early as 1733, and laws were soon established for licenses of exploitation, as well as for provisions regarding reforestation of the land.

The difficulties that these early lumbermen and their families encountered, as Molly Cabot noted, required “special energies of mind and body.” She wrote of a Mrs. Dunklee, among the earliest settlers, who was chased by wolves while traveling on horseback, “and only escaped by climbing the branches of a tree, when the horse made his way home and brought the family to her rescue.” Inspired in part by such horror stories of predatory wolves, vengeful hunters and trappers began targeting the wolves of New England. Wolves had not been welcome in the New England woods for a very long time, however. Among the first laws instituted by the Puritan settlers of the Massachusetts Bay Colony in 1630 was a bounty on wolves, which Roger Williams, who fled the colony for its religious intolerance, referred to as “a fierce, bloodsucking persecutor.” Extermination of the New England wolf was complete two centuries later; according to the Massachusetts Division of Fisheries and Wildlife, the gray wolf has been extinct in the state since about 1840, fifty years before the Kiplings arrived in Vermont.

Brattleboro played an important part in the extermination of wolves. After the free-love activist John Humphrey Noyes was banished from Putney for transgressing local moral codes, he established the Oneida Community in upstate New York, hoping that agriculture would keep his followers alive. Animal traps designed by a Noyes adherent named Newhouse proved more lucrative. Oneida wolf traps soon dominated the market, as free love and wolf hatred proved compatible with sales pitches. The Newhouse trap, according to one advertisement, “going before the axe and the plow, forms the prow with which iron-clad civilization is pushing back barbaric solitude, causing the bear and beaver to give way to the wheat field, the library and the piano.” Oneida traps were widely used in New England and the West, where strychnine inserted into buffalo corpses helped wipe out the wolf population.

At precisely the moment that wolves disappeared from New England, some prominent New Englanders began to miss them. By the mid-nineteenth century, New England sages were already lamenting the loss of wildness in both landscape and society. They invoked wolves rather than bald eagles as a sort of national icon. In the epigraph to his classic essay “Self-Reliance,” Ralph Waldo Emerson admonished his countrymen to embrace a regime of tough love—to cast their “bantlings,” their young children, into the wilderness and have them learn to fend for themselves.

Cast the bantling on the rocks,

Suckle him with the she-wolf’s teat;

Wintered with the hawk and fox,

Power and speed be hands and feet.

Henry David Thoreau expanded the allure of a Romulus-and-Remus education in the wild: “It is because the children of the empire were not suckled by wolves that they were conquered & displaced by the children of the northern forests who were.” Throwing down the national gauntlet, Thoreau added, “America is the she wolf today.”

Emerson was a particular favorite of Kipling. He felt that his adopted home in Brattleboro was underwritten by Emerson, since the Sage of Concord had written admiringly of Mount Monadnock in his poetic series “Woodnotes.” Monadnock happened to have its own conspicuous place in New England legends about wolves. The woods around the mountain had been repeatedly clear-cut and burned to prevent wolves from taking refuge in the supposed wolf pits among the rocky outcroppings. The mountain’s bare face was thus a monument to wolf hatred. Emerson’s “Self-Reliance” was more than a favorite essay for Kipling; it was a sacred creed to live by. Kipling’s poem “If—” is a recasting of Emerson’s idea of self-trust. “If you can trust yourself when all men doubt you, / But make allowance for their doubting too; / . . . You’ll be a Man, my son!” Kipling writes. Kipling’s choice of wolves for Mowgli’s ideal family may well have been inspired, in part, by the epigraph from “Self-Reliance”: “Suckle him with the she-wolf’s teat.”

The belief that there were benefits of an education in the wild was widespread by the 1890s, when there was pervasive fear in the United States that the country was becoming overcivilized, a land of sissies unprepared for the onslaught of the immigrant hordes flooding the country. Wolves, however, were not always considered a part of this idealized life in the wild. Theodore Roosevelt drew a distinction between noble wild beasts worthy of preservation—such as deer, moose, and bears—and ignoble beasts. The wolf, in Roosevelt’s view, was “the beast of waste and desolation.” Bears should be hunted; wolves should be exterminated.

5.

Kipling’s vivid narrative in the Mowgli chapters of The Jungle Book is less driven by tooth and claw—the naturalist vision of Roosevelt and Jack London—than by a psychological conflict. The abandoned man-cub Mowgli is torn between his wild identity as a brother of the wolves who take him in and his dawning sense, as he is taught by Bagheera, the black panther born in captivity, that he rightly belongs among men. “I am two Mowglis,” he laments. “These two things fight together in me as snakes fight in the spring.” For Bagheera, however, this anguished status of being in between is actually a source of strength. “Yes, I too was born among men,” Bagheera tells Mowgli, recounting his years in the private zoo of an Indian king and showing the mark of the collar on his neck, “and because I had learned the ways of men, I became more terrible in the jungle than Shere Khan.” The question for Mowgli—as it so often is for Kipling—is to find the proper balance between the claims of civilization and the claims of the wild.

In 1907, Sigmund Freud answered a request from a publisher for a list of ten good books. The books on Freud’s list were, as he put it, “‘good’ friends, to whom one owes a portion of one’s knowledge of life and one’s world view.” The second entry on Freud’s list was The Jungle Book, a great favorite of his. One can easily see why the story of a child raised by wolves appealed to Freud, who had reimagined childhood—that innocent realm of the buttoned-up Victorians—as a battleground of contending forces: sexual, aggressive, and wild. Civilization, in Freud’s view, was built on the repression of these forces, but at a considerable cost to human satisfaction. “Kipling’s lesson seems plain,” writes Peter Gay, Freud’s biographer. “Men cover up their libido and their aggressiveness behind bland and mendacious surfaces; animals are superior beings, for they acknowledge their drives.” One can see why Max, that latter-day Mowgli, wears his wolf suit when he goes on his night journey in Where the Wild Things Are. And one can see why The Jungle Book, that vivid story of adoption by wolves, was as close as Kipling came, after all his conversations with Mary Cabot, to writing the Great American Novel.