Chapter Twelve

THE FLOODED BROOK

1.

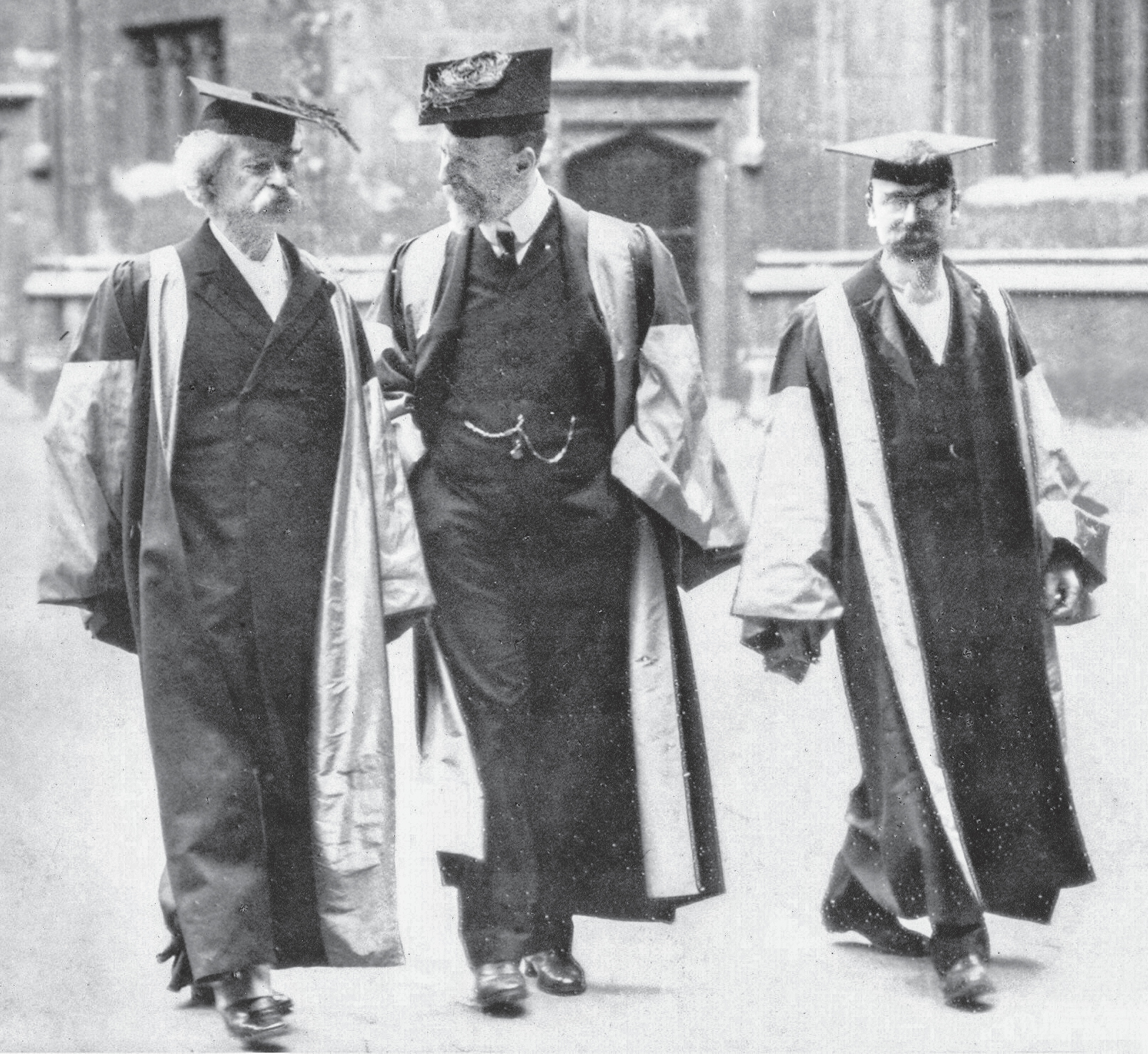

Rakishly arrayed in his “surpassingly becoming” scarlet gown, silver-maned Mark Twain relished the procession through the Oxford streets. Those destined for honorary degrees from the famous university, that summer evening in June 1907, marched “between solid walls of the populace,” Twain reported, “very much hurrah’d and limitlessly kodacked.” It was an impressive lineup: the French composer Saint-Saëns, the sculptor Rodin, among other celebrated artists and scientists. Walking immediately behind Twain was Rudyard Kipling. Neither writer had ever attended college. From All Souls, they made their stately way to the Sheldonian Theatre, amid a shower of applause.

They arrived at the theater walking two by two, as Kipling noted in a letter to his son, John, and were herded into an antechamber. There, the doctors of literature and science were informed, they would have to wait. “And we waited, and we waited, and we waited,” Kipling wrote. Mark Twain asked, in a loud voice, “if a person might smoke here and not get shot.” A horrified official responded, “Not here!” and gestured to an alcove. “So we went out,” Kipling reported, “and Mark Twain came with us and three or four other men followed and we had a smoke like naughty boys, under a big archway.”

Mark Twain (left) and Kipling (right) at Oxford, 1907.

It was a reunion of sorts, this gaggle of boisterous boys out of sight of the adoring public. Almost twenty years had elapsed since the first time that Kipling and Twain had chatted amid a cloud of cigar smoke, discussing the limits of autobiographical truth-telling and a possible sequel to The Adventures of Tom Sawyer. Since that first meeting in Elmira, Kipling and Twain, the undisputed literary lions of the English language, had remained acutely aware of one another, even as their careers sharply diverged, like mirror images of one another. Twain watched Kipling’s fortunes rise as his own declined, the result of ill-fated investment schemes and hurried writing. Kipling had settled in New England even as Twain was leaving it. Kipling gave up restlessly circling the globe just as Mark Twain began his own travels, retracing itineraries that Kipling had taken long before him.

2.

For Kipling, the years from 1899 to 1914 were a time of rewards and fairies, to borrow the title of one of his books from the period. What he called his “notoriety” had never been higher, both for the fame that he had won from his writing and for the controversy that surrounded his increasingly reactionary political opinions. A flood of honors was gratefully received or gracefully refused, according to Kipling’s determination to remain, at all costs, a free agent in his writing. The laureateship, repeatedly offered, was out of the question, nor would he consider, despite invitations, serving in Parliament. That fiercely protected freedom to follow the wayward inner promptings of what he referred to as his Daemon was exploited in the views he expressed—sometimes prophetically, in the elevated key of “Recessional,” and sometimes with extraordinary vulgarity. He alienated many friends and admirers with his jingoistic support for English colonialists in the Boer War in South Africa; in the lead-up to the Great War, he urged the British to resist German expansion at whatever cost, warning, “The Hun is at the gate!”

Kipling’s lungs had been permanently damaged from the pneumonia he contracted in New York in 1899; doctors urged him to seek, henceforth, a warmer climate for the winter months. He had visited South Africa for the first time the previous year, and returned with regularity like a migratory bird. There, he developed an intense affection for the English settlers and their leaders: Dr. Jameson of the quixotic raid against the Dutch Boers, Alfred Milner, and, above all, Cecil Rhodes, the imposing imperialist who built a rustic house for Kipling’s personal use. Kipling adopted the British cause in South Africa, as he explained in Something of Myself. When Rhodes asked him, “What’s your dream?” Kipling answered, swooningly, that Rhodes “was part of it.” The Dutch he regarded with scorn, as mere pretenders to civilization, or worse. As for black Africans, who had a far greater right to the land than either colonial power, Kipling barely noticed their existence.

Amid his strident, and increasingly repellent, engagement with global politics, these were years of intense private mourning for Kipling. With Josephine’s death, the United States had become a haunted place in his mind, never to be revisited except in the oblique approaches of his stories and verses, and in encounters with emissaries from his lost youth, like Mark Twain or Charles Eliot Norton. He found solace in travel, both in the annual family voyages to the British settlement in Cape Town—a “Paradise” for seven years, in Kipling’s view, before the Boers regained control of the country—and in motoring around the Sussex countryside in his new passion, an automobile.

But the travel that increasingly preoccupied his days and nights was a deeper plunge into the storied past. He pored over archeological accounts of the South of England, brooding on Viking raiders and stalwart Roman centurions, the counterparts of the tough-minded soldiers he had known on the Indian border. He found spiritual anchorage in the odes of Horace, the torture of his school days and the joy of his disillusioned maturity. “Do not inquire what unseen end the gods have in mind for you,” Horace had written. “Cut back far-reaching hopes and pluck the day”—carpe diem. Kipling painstakingly illuminated the margins of his Horace volumes with illustrations from his own lost worlds: American Indian peace pipes in memory of Bill Phillips, mosques from Lahore.

To native fairy tales, both freely adapted from original sources or invented from his own imaginative storehouse, he brought some of the same narrative vigor that he had applied to Mowgli’s adventures. He found relief from his emotional turmoil in composing two time-traveling volumes, Puck of Pook’s Hill and Rewards and Fairies. In these fairy realms, Kipling could mourn his losses in private. In public—to accept an illustrious award, to take part in an official commission, or to urge a political position in hammering verse—he remained firmly in control emotionally, with the iron resolution that he so admired in men like Theodore Roosevelt and Cecil Rhodes.

3.

Twain had also made his way to South Africa, traveling down from India. His qualms about Cecil Rhodes, Kipling’s hero, were not enough to make him sympathetic to the Boers, and certainly not enough for him to embrace anything like self-governance for black South Africans. And yet, unlike Kipling, Twain thought the Boer War was ill-advised, and he was shocked in particular by the ineptness of Dr. Jameson’s Raid, which Kipling regarded with some of the same reverence Northerners in the United States accorded John Brown’s raid on Harpers Ferry. If their views on South Africa differed on tactics, however, Twain still supported the British.

It was after the Spanish-American War that the two writers’ views on empire diverged most sharply. Twain had endorsed the war as long as he could persuade himself that the United States was fighting for the liberation of Cuba. But when Americans attacked the Filipino rebels they had pretended to defend, Twain’s support ended in outrage. He fiercely opposed the American occupation of the Philippines, which he considered a betrayal of all that the United States stood for, since its own adoption of the Declaration of Independence. Kipling, by contrast, not only supported the invasion at the outset, but continued to take an interest in the oppressive American regime there.

And yet Twain’s admiration for “my splendid Kipling,” as he called him, endured. In August 1906, a year before the celebration at Oxford, Twain noticed a Kipling poem in the morning papers attacking a new British policy in South Africa. The Liberal Party had regained leadership in the British Parliament, and voted for self-rule in the South African territories, effectively returning control to the majority (at least the white majority) Boers. In an intemperate poem titled “South Africa,” Kipling equated the decision with the enslavement of the British settlers in South Africa. “At a great price you loosed the yoke / ’Neath which our brethren lay,” he addressed the British people. “Our rulers jugglingly devise / To sell them back again.” Kipling, who never reprinted the poem in any of his collections of verse, evidently came to feel that he had gone too far. But instead of criticizing Kipling’s repugnant political views, Twain sought to excuse them, ascribing Kipling’s love for “power & authority & Kingship” to “his training that makes him cling to his early beliefs.”

4.

During the fall of 1907, after playing second fiddle to Mark Twain at Oxford, the Kiplings were invited to Canada for what amounted to a triumphal transcontinental tour, with a luxurious private railroad car for their enjoyment. What Kipling saw of Canadians persuaded him that this British dominion (as the colonies were called) was infinitely more civilized than its neighbor to the south. He marveled, in Something of Myself, “that on one side of an imaginary line should be Safety, Law, Honor, and Obedience, and on the other frank, brutal decivilization.” Still grieving over the death of Josephine, Kipling refused to travel across the border. Mrs. Balestier was forced to make the journey from Brattleboro to Montreal to see her daughter and son-in-law.

On his return to England, Kipling was stunned to learn that he had been awarded the Nobel Prize. He was the first writer in English to win the award and, at forty-one, the youngest. His account of the occasion in Something of Myself is in stark contrast to the frolic at Oxford earlier that year. The king of Sweden died during the Kiplings’ stormy voyage across the North Sea. Instead of the scarlet pomp of Oxford, the occasion in Stockholm, as Kipling described it, was a Whistlerian symphony in black and white.

We reached the city, snow-white under sun, to find all the world in evening dress, the official mourning, which is curiously impressive. Next afternoon, the prize-winners were taken to be presented to the new King. Winter darkness in those latitudes falls at three o’clock, and it was snowing. One half of the vast acreage of the Palace sat in darkness, for there lay the dead King’s body. We were conveyed along interminable corridors looking out into black quadrangles, where snow whitened the cloaks of the sentries.

Kipling decided that it must be from their native land that the hardworking Swedes drew their strength. “Snow and frost are no bad nurses,” he reflected. Having endured many harsh winters of their own, the Kiplings now turned their attention to putting down roots in their newly adopted northern land.

Kipling had found a house in the Sussex countryside where he hoped that his family could recover some of the life that they had treasured in Vermont: isolation, privacy, a landscape fit for livestock, hard work, and stories. Naulakha had finally been sold in 1904. The house on the crest of a Vermont hillside had been on the market for several years, an unwelcome reminder of Josephine’s death and the quarrel with Beatty. “I feel now that I shall never cross the Atlantic again,” Kipling had written his old friend, Dr. Conland, in January 1903, “all I desire now is to get rid of Naulakha for $5000.” Even the fire-sale price, sharply down from an initial offering of $30,000, was only feasible because members of the Cabot family mercifully took the house off his hands.

Henceforth, all things in Kipling’s life revolved around Bateman’s, the ironmonger’s house that he had discovered on one of his roving tours of the countryside. The house itself, without electricity or running water when Kipling bought it, dated from the sixteenth century. The River Dudwell, meandering quietly through the meadows, had once powered a small mill near the house. Earlier still, a forge had been established in Roman times; plows and hoes turned up fragments of pig iron and ax-heads. Kipling consulted with Aurel Stein, the great archeologist and associate of Lockwood in Lahore, about his findings, and his sense that he was living atop an archeological hoard.

These layers of history sparked Kipling’s imagination for Puck of Pook’s Hill and its sequel, Rewards and Fairies, in which a brother and sister, Dan and Una, modeled on John and Elsie Kipling, are introduced to the previous denizens of the Weald, the clay-rich fields and woods of rural Sussex. The books feature some of Kipling’s finest poems, including lyrical masterpieces like “Harp Song of the Dane Women” and “The Way Through the Woods.” Burne-Jones supplied the original imaginative direction of these books. Kipling had asked him about possible historical sources, and Uncle Ned had asked historians like Mommsen, the German chronicler of ancient Rome. But he had also seen a way forward in Kipling’s “‘The Finest Story in the World,’” a tale that demonstrated, Burne-Jones wrote, “what the public might look for in your treatment of an ancient subject.”

Again, Kipling turned to Longfellow, the inspiration for “‘The Finest Story.’” Reading a volume of Longfellow serves as a charm for Una and Dan, by means of which they summon a sailor familiar with Viking longboats. In “The Knights of the Joyous Venture,” the third tale in Puck of Pook’s Hill, Dan reads aloud from Longfellow’s “The Discoverer of the North Cape,” and elicits a parallel story from an English sailor kidnapped by a Danish vessel. The story is preceded by Kipling’s great seafaring poem in the Old English rhythm, “Harp Song of the Dane Women”: “What is a woman that you forsake her, / And the hearth-fire and the home-acre, / To go with the old grey Widow-maker?”

A master theme running through the stories collected in Rewards and Fairies is the nature of human responsibility. In tale after tale, Kipling places the main character in difficult circumstances where a choice must be made despite imperfect options. A recurring question is “What else could I have done?” It is the question voiced by George Washington in a pair of tales set in eighteenth-century Philadelphia, a city Kipling remembered from his 1889 travels. Set in 1793, “Brother Square-Toes” celebrates the Anglo-American alliance that Kipling had long cherished. A Sussex boy named Pharaoh Lee, son of a Rottingdean smuggler, suffers the fate of Harvey Cheyne when a French warship, in thick fog, runs down the dinghy in which he and his father are retrieving barrels smuggled from relatives in France. Pharaoh becomes a cabin boy on the warship transporting the French ambassador, Genet, to Philadelphia. Genet’s mission is to persuade George Washington to fight on the side of revolutionary France against Great Britain. Pharaoh apprentices himself in Philadelphia to a Moravian apothecary who trades with Seneca Indians in the Pennsylvania outback; they call the boy “Brother Square-Toes” for the prints that his shoes leave in the dirt.

Pharaoh accompanies two Seneca chiefs to Genet’s meeting with President Washington, called “Big Hand” by the Indians. Washington firmly rejects the French appeal, despite American opinion running ten-to-one against the British. “Deal with facts, not fancies,” he says, well aware that America, with no navy or army to speak of, is not equipped for another war. “Let me assure you that the treaty with Great Britain will be made though every city in the Union burn me in effigy,” he insists. When Big Hand finishes his ringing speech, “it was like a still in the woods after a storm.”

“Brother Square-Toes” is immediately followed, as an epilogue illustrating and enlarging the story, by Kipling’s great poem “If—.” Story and poem praise the immovable man, unswayed by public opinion, whether praise or blame. Kipling invites us to see Washington as the quintessential embodiment of the steely resolve described in the poem. Familiar lines from the poem assume a fresh meaning when they are associated with President Washington, who refused the title of king: “If you can talk with crowds and keep your virtue, / Or walk with Kings—nor lose the common touch. . . .” Kipling finds his ideal of public comportment in an American leader, and in an American setting.

5.

A prominent feature of the extensive Bateman’s grounds, and of the two Puck books, was a bubbling brook called Dudwell, at the foot of the garden, charmingly picturesque in most seasons but given to ruinous flooding without notice. “The waters shall not reckon twice / For any work of man’s device,” Kipling wrote in “The Floods.” The brook became an idiosyncratic character in his life and his fiction, as lively and unpredictable as any of his friends or neighbors. It became, indeed, something like the spirit of the place itself, to be loved and treasured but also, as a local deity, feared and propitiated. Drainage was a constant challenge. “We’ve been fighting floods in our valley—putting in pipes and drains and trying to persuade our innocent looking little brook that it isn’t a Colorado river—so far without success,” Kipling wrote in 1911.

Kipling compared his own efforts to control the not-so-innocent brook with the industry of his beloved beavers. “Except for three days of light snow-powder every hour has been usable in the open and we’ve worked like beavers cutting wood, putting in great water-drains under roads, setting up fences, hauling faggots etc. etc.; always with one eye on our Rogue River—the innocent brook that has already flooded us once this year,” he wrote, before enlarging the comparison.

I suppose God gave us superfluous energy the same way he gave the Beaver incisors that have to grow; and for fear our mental incisors should end by growing on and on and curving back and piercing our brains, he invented the whole generation of stubborn, ox-eyed, mule-hearted, mud-footed farmers in lieu of the Beaver’s wood stumps. So we all run about chewing and biting and carrying mud in our forepaws . . . and slapping our tails to the greater glory of God and, I hope, the advantage of the land.

The brook at the foot of the garden inspired, in its seasonal permutations, some of Kipling’s most vivid stories during his English years. “‘My Son’s Wife’” strands a progressive young urbanite named Midmore in a country estate inherited from a deceased aunt. At first, the land—with its stubborn old tenant farmer named Sidney, its house too close to a “dull, steel-colored brook,” and its foxhunting neighbors—seems a burden, to be sold off as soon as possible. Midmore is dismayed to learn from his local lawyer, Sperrit, that the property is encumbered by various liens, nor is it worth as much as he had hoped. “The repairs are rather a large item—owing to the brook,” says the classically trained lawyer. “I call it Liris—out of Horace, you know.” The ode alluded to asks what the poet wants from Apollo, and answers, “not an estate which is gnawed by the Liris, that silent river, with its gentle stream.”

As his name suggests, Midmore, like so many of Kipling’s characters, is caught between two worlds. The twin tasks of repairing the farm and riding to the hounds awaken feelings in himself that he had been unaware of. The brook is the anarchic wild force in the story. When it floods to record levels, it dredges up one love story from the deep past (Sidney and Midmore’s loyal housekeeper, Rhoda) and stirs up another in the present (Midmore and Connie Sperrit, daughter of Midmore’s Horace-quoting lawyer, and an avid horsewoman). The flood is a Darwinian test, dividing the fit from the unfit: “Now what is weak will surely go, / And what is strong must prove it so.”

6.

A favorite escape for Kipling, amid all the work on the Bateman’s property, was motoring around with his car and driver—he never drove himself—in the Sussex countryside. He paid visits to Henry James, who lived nearby, and other neighborhood acquaintances. But if driving was a distraction, from his work and his losses, it was also ghost-ridden. The car as a vehicle of time travel and the death of Josephine are united in one of Kipling’s greatest achievements, the eerie ghost story titled “They.”

The narrator is a grieving father. On a pleasant drive in early summer, he finds himself “clean out of my known marks.” He passes through a village named Washington, “which stands godmother to the capital of the United States.” At a crossroads, amid the “confusing veils of the woods,” he has no idea which road to take. He stops to ask for directions at an “ancient house of lichened and weatherworn stone.” The tenant, a blind woman, seems somehow aware of his own loss. He notices children looking out from the upper windows. “Oh, lucky you!” the woman cries, apparently, he assumes, because she is unable to see them, but actually, as he soon learns, because they are visible to him. The children shy away from the narrator’s approach, vanishing into the underbrush outside or the shadows within. On a second visit, the car itself seems to know the way to the dilapidated house in the woods.

“They” is structured like a detective story, in which the identity of the children is concealed from the grieving narrator even as the reader gradually surmises the true state of affairs. The moment of revelation comes only on the third visit, amid falling leaves at summer’s end. Having tea with the blind woman, the narrator is again aware of children hidden in the shadows, shyly keeping their distance like scared animals. As a way to build their trust, he pretends to be unaware of them, “when I felt my relaxed hand taken and turned softly between the soft hands of a child.” The gesture was a “mute code” devised between father and living child “as the all-faithful half-reproachful signal of a waiting child not used to neglect even when grown-ups were busiest.”

“Then I knew,” says the narrator. The blind woman, he realizes, is a medium with psychic powers, capable of calling up ghosts from the spirit world. The house in which she lives is haunted by the ghosts of dead children, who can be summoned into the presence of those mourning their deaths. This reunion across the barrier of death is immediately followed by the narrator’s firm decision never to return to the haunted house. “For me it would be wrong,” the narrator tells the blind seer, wrong to trespass on the sacred precincts of the dead.

7.

Kipling’s resolve to close the portals of the dead was tested again at the outset of the Great War. His only son, John, was not yet seventeen. Like his father, Jack, as he was known, had bad eyes, but he was determined to join in the war effort. Rejected for an officer’s commission, he tried to enlist as a private instead, again without success. His father pulled strings and Jack was enrolled as a junior officer in the Irish Guards. On his first day of battle, almost his first hour, at the hideous arena of mechanical warfare amid the trenches of Loos, in Belgium, Jack was reported missing, presumably blown to pieces by a German shell. No remnant of his body was ever recovered.

After the war, Kipling accepted a position on the Imperial War Graves Commission, charged with honoring the memory of the war dead. In this capacity, he traveled often to France and composed the official inscription on the British graves. He also wrote, in a less official vein, the darkly moving “Epitaphs of the War,” in which he left far behind the saber-rattling jingoism of his prewar verses. “Who dies if England lives?” he had asked at the outset of the war. In his heartbreaking elegy for Jack, with its prevailing metaphor of a wreck at sea, he gave the answer.

“Have you news of my boy Jack?”

Not this tide.

“When d’you think that he’ll come back?”

Not with this wind blowing, and this tide.

“Has any one else had word of him?”

Not this tide.

For what is sunk will hardly swim,

Not with this wind blowing, and this tide.

For two years, Jack remained officially missing, but Kipling knew differently. “The wife is standing it wonderfully tho’ she, of course, clings to the bare hope of his being a prisoner,” Kipling confided to a former classmate serving in the army. “I’ve seen what shells can do, and I don’t.” Predictably, spiritualists wrote to Kipling promising to put him in touch with his lost son. A visit from Trix, deep in her own clairvoyant fantasies, augmented his frustration. “I have seen too much evil and sorrow and wreck of good minds on the road to Endor,” he wrote in Something of Myself, alluding to a sorceress in the Book of Samuel, “to take one step along that perilous track.” He put his objections into verse in the wartime poem “En-Dor,” in which he acknowledged the temptation: “Whispers shall comfort us out of the dark—/ Hands—ah, God!—that we knew!”

8.

And then, unexpectedly, someone touched Kipling’s arm again, touched it not once but twice. It began with a dream.

I dreamt that I stood, in my best clothes, which I do not wear as a rule, one in a line of similarly habited men, in some vast hall, floored with rough-jointed stone slabs. Opposite me, the width of the hall, was another line of persons and the impression of a crowd behind them. On my left some ceremony was taking place that I wanted to see, but could not unless I stepped out of my line because the fat stomach of my neighbor on my left barred my vision. At the ceremony’s close, both lines of spectators broke up and moved forward and met, and the great space filled with people. Then a man came up behind me, slipped his hand beneath my arm, and said: “I want a word with you.”

A few weeks later, Kipling attended a ceremony at Westminster Abbey, in his official capacity as a member of the Imperial War Graves Commission. The Prince of Wales was there to dedicate a plaque in honor of the million dead in the Great War.

We Commissioners lined up facing, across the width of the Abbey Nave, more members of the Ministry and a big body of the public behind them, all in black clothes. I could see nothing of the ceremony because the stomach of the man on my left barred my vision. Then, my eye was caught by the cracks of the stone flooring, and I said to myself: “But here is where I have been!” We broke up, both lines flowed forward and met, and the Nave filled with a crowd, through which a man came up and slipped his hand upon my arm saying: “I want a word with you, please.”

What Kipling describes is a striking example of what the Society for Psychical Research referred to as a “predictive dream.” Mark Twain had also had such a dream when he and his brother, Henry, were training to be riverboat captains. Twain dreamed in great detail that his younger brother’s body, draped with white roses and a single red one, was placed in a casket balanced across two chairs. So vivid was the dream that when Twain awoke, he was relieved to find his brother alive and well. Three days later, Henry was killed in a steamboat explosion. Twain hurried to the scene to find his brother in a metal casket, balanced between two chairs. “A volunteer nurse stepped up to the coffin and gently laid across it a bouquet of white roses with a single red bloom in their midst.” Twain joined the Society for Psychical Research on the basis of the dream.

Kipling was wary of such moments of apparent clairvoyance. “For the sake of the ‘weaker brethren’—and sisters—I made no use of the experience,” he wrote, alluding, it would seem, to his own sister. It wasn’t that he didn’t believe in such occult events. The point was that he did believe in their reality, and in their danger. Of his own predictive dream, he allowed himself only one comment, and he put it in the form of a question. “But how, and why, had I been shown an unreleased roll of my life-film?” It is a striking metaphor. Kipling, who was intensely interested in the new technology of motion pictures, imagines each human life as a spool of film unrolling over time. On certain occasions, and without explanation, the ordinary chronological deployment is violated, and we are given a momentary glimpse of the future or the past.

Kipling, as it happened, was given access to both the past and the future as he stood, first in dream and then in reality, in the vast hall with the cracks in the stone floor. The ceremony at Westminster Abbey was emotionally overloaded for him. He was a commissioner of war graves, but he was also the grieving father of one of the million dead. Who exactly was the stranger in the crowd, who slipped his hand under Kipling’s arm and said, “I want a word with you, please”? Could he be anyone other than an emissary from the land of the dead? This stranger repeats the gesture of the shy daughter in “They,” who takes her grieving father by the hand. It is also the gesture of the lost son in “En-dor”: “Hands—ah, God!—that we knew!”

The dream of Westminster Abbey was to be doubly predictive, as Kipling surely knew. For even as he was hurriedly writing Something of Myself, Kipling was certain that he himself did not have long to live, and that death would soon take him by the hand and ask to have a word with him. As the most celebrated English writer of his age, Kipling could be confident that his own last reward would be a memorial in Westminster Abbey. And so it was that when he died, just after his seventieth birthday, his ashes were buried in Poets Corner, alongside the graves of Chaucer and Tennyson. The funeral service was held amid a great crowd in the vast hall with the cracked stone floor.