Margaret Bourke-White

Hillary

As I did with so many inspiring women from my childhood, I first met Margaret Bourke-White, the fearless photojournalist, in the pages of Life. From the moment I saw her photos and read the startling description of her as the “first female war correspondent,” I was hooked. I wanted to learn more about the person behind the lens, who documented everything from Depression-era breadlines to the front lines during World War II.

Margaret was born in the Bronx just after the turn of the twentieth century, raised by parents who encouraged her to be brave and independent. Whenever her mother, Minnie, found out that one of her children had discovered a new interest, she would leave books on the subject around the house for them to find. Margaret’s father, Joseph, an engineer, was interested in the burgeoning field of photography and printing. Margaret remembered him as “the personification of the absent-minded inventor. I ate with him in restaurants where he left his meal untouched and drew sketches on the tablecloth. At home he sat silent in his big chair, his thoughts traveling, I suppose, through some intricate mesh of gears and camshafts. If someone spoke he did not hear.” As a little girl, Margaret followed him around while he took photographs, carrying an empty cigar box as her “camera” and helping him develop pictures in the family’s bathtub. He brought her to factories and foundries, where she was awestruck by the heavy machinery and flying sparks.

Margaret was fascinated by her father’s work. But she was more interested in looking at insects through a magnifying glass, collecting turtles and frogs, and poring over maps. “I pictured myself as a scientist,” she said, “going to the jungle, bringing back specimens for natural history museums and doing all the things that women never do.” After graduating from high school, she enrolled at Columbia University in New York to study art. That year, Minnie bought Margaret her first camera, a twenty-dollar Ica reflex with a cracked lens. Perhaps driven by her explorer’s spirit, she bounced from school to school, never staying for long in one place or with one major: She studied art, swimming, dancing, herpetology, paleontology, and zoology. After six universities and one brief marriage, Margaret transferred to Cornell, her seventh; she chose it because she’d heard there were waterfalls on campus.

At Cornell, she discovered her calling. After struggling to find a part-time job to support herself, Margaret took the camera her mother had given her and used it to photograph the buildings on campus, selling the images to fellow students and the alumni newspaper. Soon she started getting calls from architects who wanted to know whether she was studying to become a photographer—something she had, up to that point, never considered. One day before graduation, she marched unannounced into the offices of York & Sawyer, a major architectural firm, with a folder full of her photographs, demanding an unbiased opinion of her work. She left assured that she had a future in architectural photography, if she wanted it.

After graduation, Margaret moved to Cleveland, her sights set on photographing the city’s steel mills. Even though the mills were closed to women, she talked her way in with her camera. “Nothing attracts me like a closed door,” she said later. “I cannot let my camera rest until I have pried it open.” The same fascination with industrialization that she first experienced as a child was evident in her pictures, which provided an up-close look at a changing American economy.

“By some special graciousness of fate I am deposited—as all good photographers like to be—in the right place at the right time.”

—MARGARET BOURKE-WHITE

Margaret’s photos caught the eye of Henry Luce, the publisher of Fortune magazine, and she signed a part-time contract. The magazine eventually sent her to Germany, then to the Soviet Union. Though the latter was as closed to journalists as the Cleveland steel mills were to women, Margaret wouldn’t take no for an answer. She lobbied the Soviet embassy in Germany for weeks, and the officials there finally relented; she became the first foreign photographer to gain unlimited access to the region in 1930.

Back in the United States, she signed on to a book project working with the writer Erskine Caldwell, who would become her second husband. It required the two of them to travel together for months on end. Margaret, used to working on her own, didn’t take kindly to Caldwell’s instructions. They had barely left home when he tried to call off the trip because the two weren’t getting along. Ultimately, Margaret felt the book was important and decided to do everything she could to make the project work. The end product was You Have Seen Their Faces, a book documenting people and families in the South.

In 1936, her photograph of Montana’s Fort Peck Dam debuted on the first-ever cover of Life magazine. The stunning black-and-white image showed a towering concrete structure that looked almost like a castle, a symbol of economic revitalization during the Depression. Her photos were used not just as captivating images to supplement a story but to comprise the first photo essay. The issue sold out in hours, and the photograph would later become a postage stamp as part of a series about America.

While working as a staff photographer for Life, Margaret also spent time in Czechoslovakia and Hungary, photographing the rise of Nazism. She and Caldwell traveled through Europe, recording the violence and anti-Semitism they saw. They worked in combat zones and, in 1941, traveled to the Soviet Union just as Germany was invading. As bombs exploded around them, Margaret and her husband hid from the officers who were evacuating residents, which allowed her to take the only photographs of the attack. Her book Shooting the Russian War is a candid behind-the-scenes look at her tour through China and the Soviet Union.

When Margaret returned to New York, she took a job at a local paper, at Caldwell’s urging, that would allow her to stay close to home. But to her, the daily assignments and low-resolution snapshots were deeply unsatisfying. Though her husband pressured Margaret to have a child, she couldn’t bear to give up her career or her independence, and she returned to Life (I’m grateful I didn’t have to choose between my work and having Chelsea!). When she informed Caldwell that she was going back to England to photograph American B-17 bombers headed to war, he asked for a divorce.

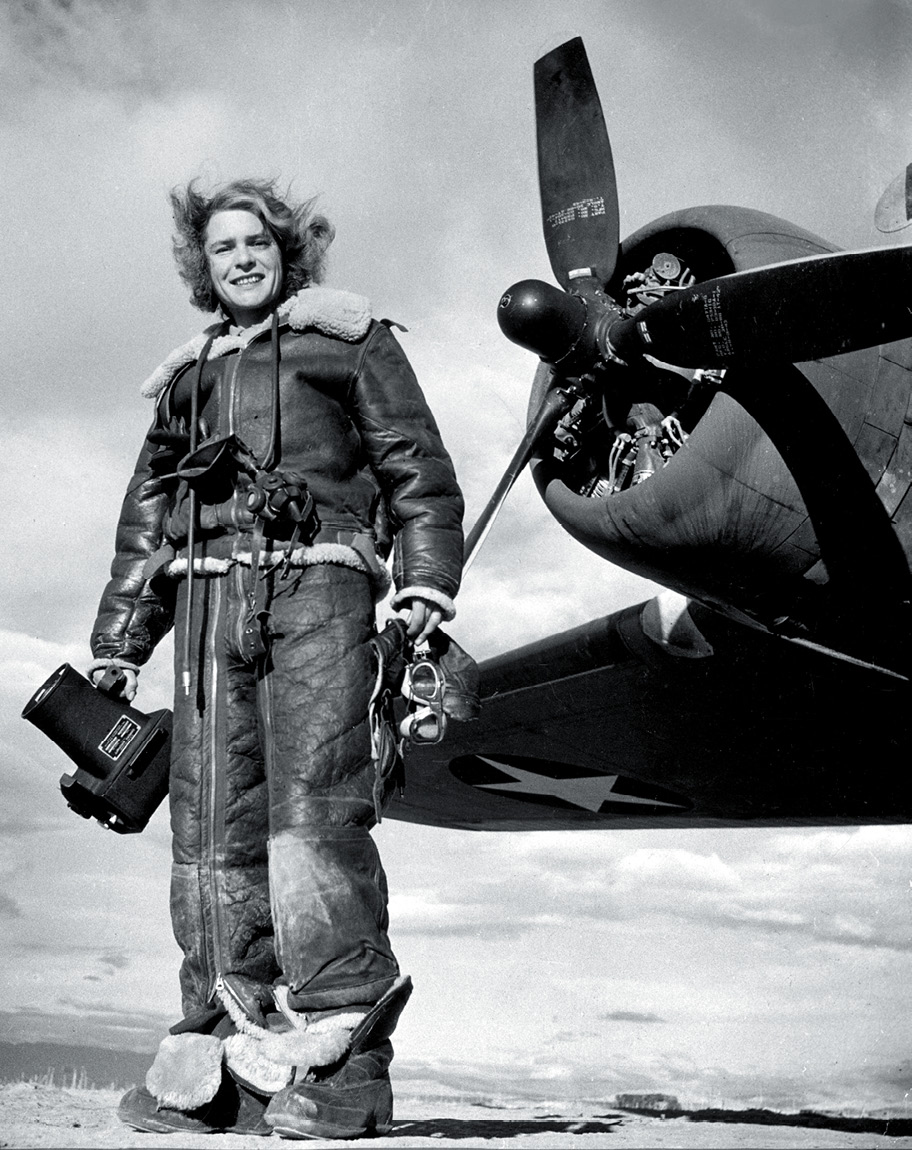

Margaret became the first female war correspondent accredited by the U.S. military. When she learned about top-secret plans to invade North Africa, she sought permission to follow Allied troops. When the boat she was traveling on came under torpedo attack, Margaret escaped on a lifeboat, snapping photographs with the one camera she managed to rescue. She moved with American troops through Italy and Germany, reporting along the way. She later said she had never been as scared as she was on the front in Italy, with enemy fire raining down around her. When General Patton’s troops marched across Germany in 1945, Margaret was there, too. She photographed the horrors of Nazi Germany and the liberation of concentration camps. She didn’t tell anyone until after she returned that her father was Jewish, adding an even more painful dimension to what she saw. I recently came across this description of her by author Sean Callahan: “The woman who had been torpedoed in the Mediterranean, strafed by the Luftwaffe, stranded on an Artic island, bombarded in Moscow, and pulled out of the Chesapeake when her chopper crashed, was known to the Life staff as ‘Maggie the Indestructible.’ ”

By the end of her career, she had photographed the Great Depression, the Dust Bowl, World War II, Gandhi in the midst of the struggle for Indian independence, and apartheid in South Africa. All told, she published eleven books.

Guided in part by her example, I declared in seventh grade that I wanted to be a journalist. I wrote a column for our school newspaper and visited the offices of one of the local Chicago newspapers for a school report. Although I eventually decided on another path, Margaret’s determination, her independence, and her fearless explorer’s spirit left an impression that has stayed with me throughout my life.