Jackie Joyner-Kersee and Florence Griffith Joyner

JACKIE JOYNER-KERSEE

FLORENCE GRIFFITH JOYNER

Chelsea

When Jackie Joyner-Kersee was born in 1962, her parents named her after Jacqueline Kennedy. After all, as her grandmother announced: “Someday this little girl will be the first lady of something.” (Prescient words for the future first lady of track!) Her home in East Saint Louis, Illinois, was very different from the Kennedy White House in Washington, D.C. Jackie and her brother, Al, grew up across the street from a liquor store and a pool hall. At eleven years old, Jackie saw a man shot outside her house. Her parents wanted a different, brighter future for their children. Jackie focused on school, where she graduated in the top 10 percent of her class. And she didn’t excel only in the classroom.

“I don’t think being an athlete is unfeminine. I think of it as a kind of grace.”

—JACKIE JOYNER-KERSEE

As a teenager, Jackie won the National Junior Championships in the pentathlon, a competition in five different track events. She would go on to win the title three more times. She set the Illinois high school girls’ long jump record. In addition to track, she competed in volleyball and basketball. After graduation, she earned a scholarship to the University of California, Los Angeles. There, she competed in the long jump and on the basketball team. Even when she was a young woman, it was clear that Jackie’s talent was bigger than any one event or even one sport.

In 1984, she made the Olympics, where, despite a pulled hamstring, she won a silver medal in the heptathlon, her signature event. The heptathlon consists of seven events over two days: 100-meter hurdles, high jump, shot put, 200-meter dash, long jump, javelin, and 800-meter run. She would later become the first athlete to score over seven thousand points in the event. Jackie is the first person I remember watching throw a javelin or a shot put. It wasn’t a man who defined these acts of precision and strength for me—it was Jackie.

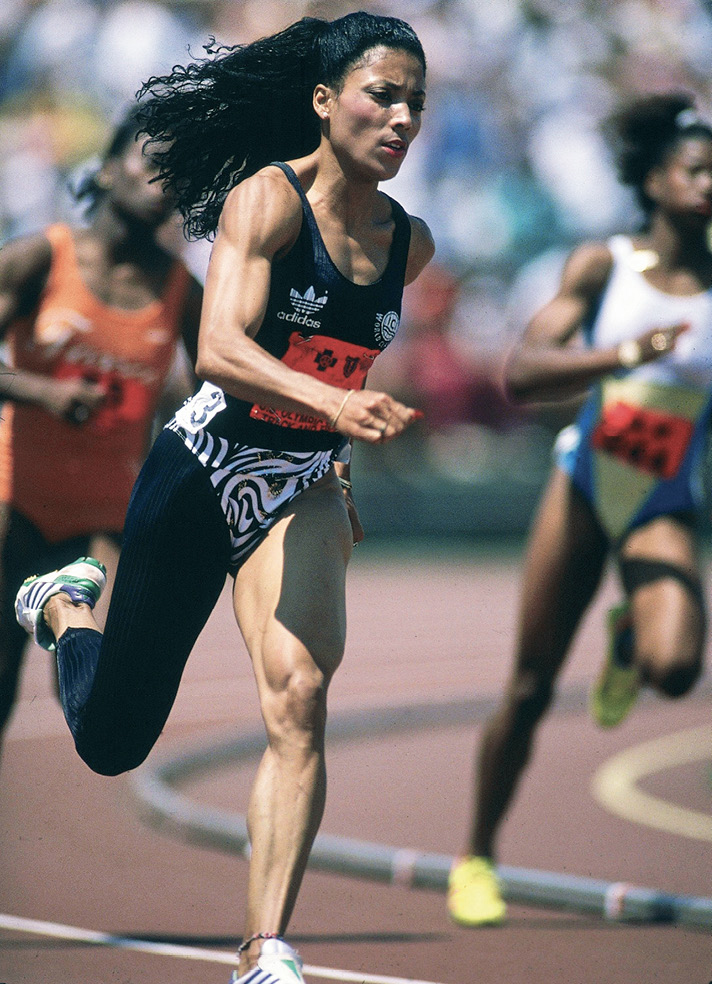

Jackie’s coach, Bob Kersee, believed in her, on the track and off. And in 1986, she married him. He told her, only half joking, that he wouldn’t let her take his name until she set a world record. That year, at the Goodwill Games in Moscow, she did. At the 1988 Olympics, she set her fourth world record and won the gold medal in the heptathlon. At that same Olympics, Jackie’s sister-in-law, Florence “FloJo” Griffith Joyner, broke the 100- and 200-meter world records. She still holds those records more than thirty years later; the men’s record in the 100-meter, in the same period, has been broken twelve times. I cheered so hard for FloJo and Jackie from home in Little Rock that I went hoarse. Jackie’s Olympic career didn’t stop in 1988; four years later, in 1992, she became the first athlete to win the heptathlon in back-to-back Olympics.

Jackie and FloJo were both targets of those who felt the need to demean the talent, skill, and strength of women athletes—particularly black women athletes—by suggesting they had resorted to steroids. Neither ever failed a drug test. FloJo passed eleven in 1988 alone. “I do not take steroids,” Jackie said. In fact, having grown up around substance use disorders and addiction, she made it clear that she stayed away from drugs and alcohol altogether. In her journal the year she was publicly accused, she wrote that there was nothing she could do to change other people’s opinions of her. “I questioned whether maybe it was the work of the devil, trying to distract me from what I can do, testing my faith. But deep down, I knew I didn’t do anything wrong.” In the meantime, she kept doing what she did best: working hard and competing. She refused to let others’ doubts discourage her.

Before she became an Olympian, FloJo was asked by a teacher what she wanted to be when she grew up. She answered: “Everything.” FloJo brought her everything to all she did, on and off the track. When she had to leave college to help support her family, she worked as a bank clerk and part-time hair stylist, training at night when she could. She qualified for two Olympics, winning her first medal, a silver, at the 1984 Los Angeles Games. She won three golds at the 1988 Seoul Games, running with her gorgeous six-inch-long nails painted red, white, blue, and gold. After she stopped racing, FloJo continued to support young athletes and became a fashion designer. Both were continuations of her life and work, since she’d started making her own track uniforms in high school. She died tragically young, at the age of thirty-eight, of an epileptic seizure. Her legacy is one of speed, style, and determination. And she remains, deservedly, to this day, the Fastest Woman in the World.

After Jackie retired from Olympic track, she played professional basketball, devoted even more time to the foundation she had started for at-risk youth, and encouraged other athletes to dedicate their time and talents, when not competing, to helping others. She understood that while talent is universal, opportunity is not, and she has spent her life trying to level the playing field so more young people can be “everything.”