Marjory Stoneman Douglas

Chelsea

Marjory Stoneman Douglas published her first piece at sixteen and never stopped writing. As a young woman, she helped care for her sick mother, a concert violinist, after her parents’ divorce, while also pursuing her studies. Like my mom, she went to Wellesley College and was very active on campus, notably in the women’s suffrage movement. Unlike my mom, she graduated with a perfect grade point average!

In 1915, in her midtwenties, after her mother passed away and after her own divorce, she followed her father to Florida. (Her ex-husband may or may not have been officially separated from his last wife and spent time in jail for writing bad checks shortly after marrying Marjory. “I left my marriage and all my past history in New England without a single regret,” Marjory said later.) In the then small town of Miami, her father published what would become the Miami Herald. While Marjory’s initial job was as a society columnist, she quickly began to cover other topics, including women’s rights, civil rights, and nature—notably, the Florida Everglades, the only subtropical preserve in North America. The conventional wisdom at the time, in the 1910s, was that the Everglades weren’t particularly special. Marjory set out to convince people otherwise.

Marjory loved her job, and she cared deeply about her country. The following year, she joined the Naval Reserve and then the Red Cross to help care for World War I refugees. After the war, Marjory wrote for the paper and for other publications as a freelancer. She tackled issues related to public health, urban planning, women’s suffrage, civil rights, and Prohibition, and also wrote essays, plays, and books. In the early 1940s, she found what would be the work of the second half of her life: celebrating and preserving the Everglades. She was even more determined that Floridians would recognize how special the Everglades are. She worried that Floridians didn’t understand what was at stake: a vital, unique ecosystem and their own health. Today, one out of every three people in Florida depends on the Everglades for their drinking water.

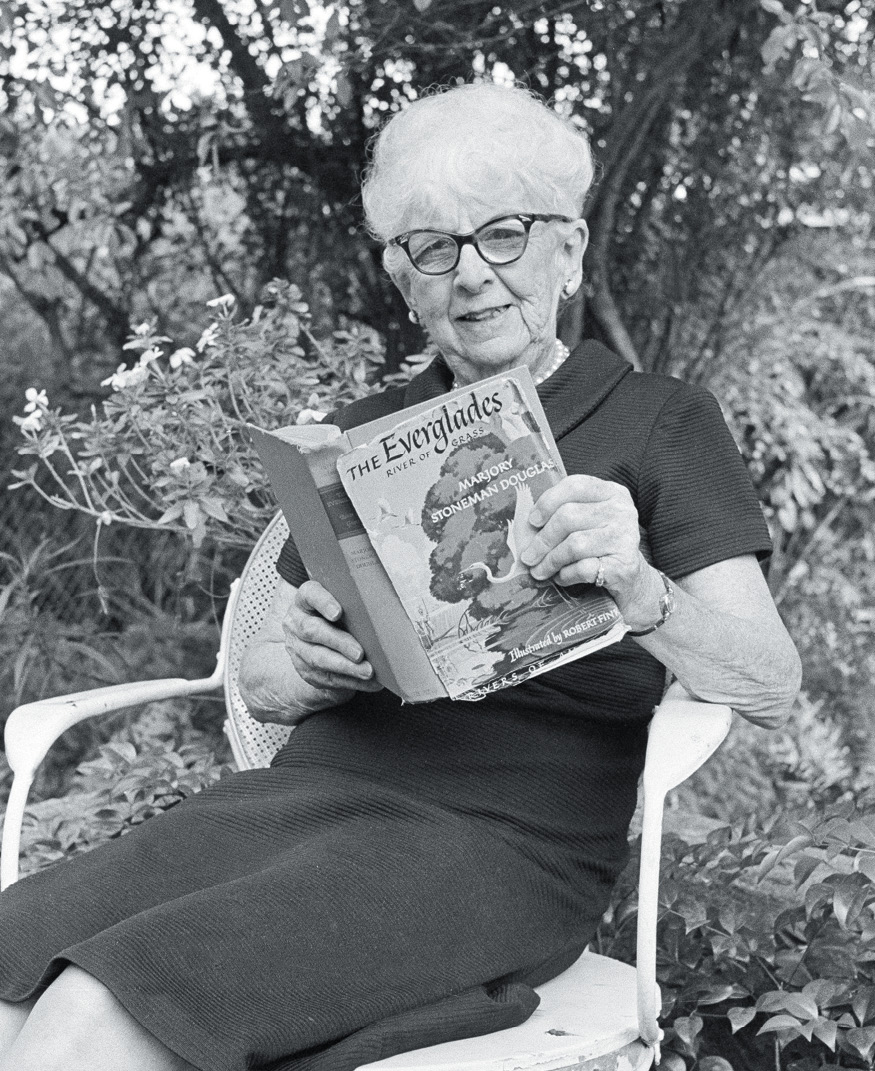

In the summer of 2018, I read her seminal work, The Everglades: River of Grass. Published in 1947, the same year the Everglades opened as a national park, Marjory argued that the Everglades is not a swamp but a river. She made a forceful case that its exceptional environment of plants and animals merits protection. Her beautifully written and illustrated book grew out of extensive study and reporting on the Everglades. It took her five years to research and write.

HILLARY

I first heard about Marjory through our alma mater, Wellesley College. She had graduated with the title of class orator, which turned out to be very apt! I wanted to meet her, so on a trip to Miami in January 1992, I visited her at her home in the Coconut Grove neighborhood. I arrived late in the afternoon to see the “Grandmother of the Glades.” At the time, she was 101. As our visit started, she informed me that she always had a glass of scotch at five p.m. and asked me to join her, which I did.

In 1993, my husband awarded her the Presidential Medal of Freedom for her conservation work. She wanted to accept it in person despite how hard travel was for her, so we invited her to come a day early and stay at the White House to rest up and prepare for the ceremony. I’ll never forget the night Marjory spent in the White House at 103 years old! It may well be that she was the oldest person to sleep in the White House. I’ve always thought it fitting that students at her namesake school are following her lead in doing their part to build a better, safer America. She and they are an inspiration.

Marjory didn’t stop her advocacy after publishing River of Grass—far from it. She continued working to protect Florida’s wetlands, taking on developers, industrial farms, and the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. I think Marjory’s straight-talking, no-nonsense approach would resonate today, as would her gutsiness. She once said in an interview that the tension between nature and humans’ interactions with it “is an enormous battle between man’s intelligence and his stupidity. And I’m not at all sure that stupidity isn’t going to win out in the long run.”

“I am neither an optimist nor a pessimist. I say it’s got to be done.”

—MARJORY STONEMAN DOUGLAS

Still, Marjory clearly had faith in us to ultimately do the right thing for nature and ourselves. Otherwise, I don’t think she would have worked as tirelessly as she did. We’re hurtling toward a tipping point in being able to prevent catastrophic global warming and its consequences. Whether we succeed in mitigating the effects of our coming climate catastrophe or not will hinge on how we treat our natural resources, something Marjory understood throughout her remarkable 108 years.